A week and a half ago I finished the manuscript for the third book in my Jupiter Pirates [1] series, capping a fairly exhausting run of writing and travel that began last August. (Which is one reason, besides Wilpon-related apathy, that Greg — APPLAUSE!!! — has been a full-time presence at the helm this offseason.) While laboring, I comforted myself with daydreams about what I’d do when I got a break in my schedule. Most of it was the kind of boring stuff you’d expect from a 45-year-old — I’m embarrassed to admit that on the first day of my leisure I got up early and cleaned out a utility closet — but what I really wanted to do was Mets-related.

What I really wanted to do was make some Mets baseball cards.

I tiptoed into this rather strange hobby a few years back when I made nine cards for the legendary Lost Mets [2], the players who appeared for the Mets but never got a decent Topps card, minor-league card, oddball reprint or anything else. (The members of this forlorn club: Al Schmelz [3], Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes [4], Tommy Moore [5], Bob Rauch [6], Greg Harts [7], Brian Ostrosser, Rich Puig [8] and Leon Brown [9]. More details here [10].) Originally the idea was that the Lost Nine would then be able to claim their places in The Holy Books. But as with many other hobbies of mine, I wound up falling down a rabbit hole to God knows where.

Before I really noticed I’d done it, my goal shifted from the Lost Nine to a larger though still unfortunate group: the players who played for the Mets but never got a card as a Met, or a good minor-league card with a color picture, or had to share a rookie card with one or more other guys. “Modern” minor-league cards date back to around 1978, so we’re talking Mets from before the Torre era — your Don Rowe [11]s and Ron Herbel [12]s and Jay Kleven [13]s and Doc Medich [14]es. (For whatever reason I don’t really care about modern-era players stuck with other teams’ cards. Maybe I will someday.) That change in focus led me to scour eBay for decent photos, to start buying transparencies of photos shot by Topps over the decades, and to make lists of which players need revisiting.

Making custom baseball cards isn’t particularly hard, but it’s time-consuming — it’s a whole lot of typing stats, scanning and endless tweaking in Photoshop, particularly since I like to work in crabbily analog ways, such as by assembling player names ransom-note style from other cards instead of finding a similar font and simply typing. (I like the funky, imperfect look this gives you — at least for this child of the ’70s, the more digital something is the chillier it feels.) This isn’t to say that making baseball cards isn’t fun if you have the right mindset — it’s the kind of meditative work I like to disappear into. But it’s not something you can budget a hour here and there for. You start and you work, and you work some more, and when you look up hours or even days have been eaten up.

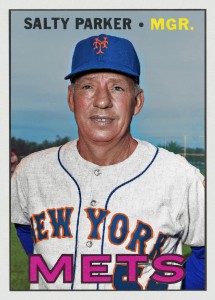

Anyhow, this madness spun off its own sub-madness: I decided The Holy Books needed to include cards for the Mets’ managers, which meant creating custom cards for Joe Frazier [15] (who only ever appeared as a Met on a team card) and for interim skippers Roy McMillan [16] and Salty Parker [17]. (Mike Cubbage [18] had a coach card in an obscure 1990s Topps set — close enough.) Frazier wasn’t too difficult — I bought a transparency of him from Topps, thus answering whatever Topps employee thought “who the hell is going to buy THIS?” McMillan led me to scouring yearbooks for a picture from the 1970s, so far without particular success. (If you can help, holler.) And then there was Parker — a coach for only a year who’d never had a color picture taken as far as I could tell.

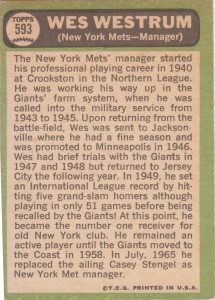

Faith and Fear pal Warren Zvon [19] rode to the rescue with a nifty colorization that he was kind enough to share (you can see the finished results and an explanation of how it was done in this post [20], with my card below) and I decided to make a ’67 Topps manager card for Parker. Such a card never could have existed — Wes Westrum [21] resigned in September and Gil Hodges [22] took over for ’68 — but never mind that.

The front of the ’67 was fairly straightforward, but then I turned over Westrum’s manager card and my eyes popped. Someone from Topps had written a full-card bio of Westrum, waxing positively Proustian. It was nearly three in the morning and I knew basically nothing about Salty Parker. There was no way I was tackling that in the middle of the night — and I wasn’t particularly looking forward to digging into it come morning, either.

But here’s the thing: Salty Parker turns out to be a really interesting guy, one of those lifers who defines baseball more than the All-Stars and MVPs do.

Francis James Parker — the nickname came from the fondness for salted peanuts that a teenaged Salty displayed while working in a grocery store — was born in East St. Louis and grew up in Granite City, Ill. He first played pro ball as a 17-year-old for the Moline Plowboys, a Class D team in the Mississippi Valley League managed by his uncle Riley. To keep his college eligibility, Parker initially played under the alias Charlie Francis. After Moline he played for the Beaumont Explorers in the Texas League, and then for the Toledo Mud Hens.

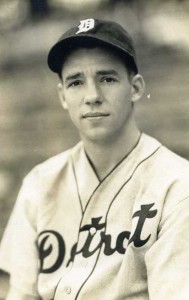

In 1936 the Detroit Tigers were world champs, having beaten the Cubs in six games. But they weren’t a particularly happy club, and player-manager Mickey Cochrane [24] was threatening to shake things up. In July he put shortstop Billy Rogell [25] in his crosshairs by acquiring the contract of 24-year-old Salty Parker from Toledo.

Parker didn’t play for a month, though his arrival in Detroit was still memorable, as we’ll see in a bit. He got into 11 games in all, hitting .280. The Tigers finished second, 19 1/2 games behind the Yankees. And in December they sent Parker to Indianapolis in the American Association as part of a deal for pitcher Dizzy Trout [27].

In 1937 Parker broke his shoulder playing for Indianapolis, torpedoing his chances of returning to the big leagues as a player. But he still had a lot of baseball ahead of him. He went back to the Texas League, playing for Tulsa and Shreveport and Dallas, and in 1939 asked for his release so he could take a job managing the Lubbock Hubbers of the West Texas-New Mexico League.

The 26-year-old player-manager hit .313 and led Lubbock to the pennant. The next year, he hit .349 as player-manager of the East Texas League’s Marshall Tigers, winning another pennant and a batting title. That got him a ticket back to the Texas League as player-manager for the Shreveport Sports. He stayed there two years, but the Texas League closed up shop because of the war. In ’43 Parker was on to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association. St. Paul became part of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ farm system the next year, and Parker had a deal with Branch Rickey [28] to manage the club — but he was drafted and spent the year in the army. In ’45 he returned to baseball, but for the first time in seven years he wasn’t a manager — he was the starting second baseman for the Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s top farm club. Parker hit .298; his replacement on the ’46 club was some guy named Jackie Robinson [29].

With the war over and the Texas League back in business, Parker returned to Shreveport for six years as manager, his playing time gradually diminishing to a few games a year, and none at all in 1951. From ’52 to ’54 he managed in the Big State League, piloting the Temple Eagles and then the Tyler Tigers. (In ’52 the 39-year-old manager somehow wound up as the starting pitcher in 13 games, amassing a 6.86 ERA.)

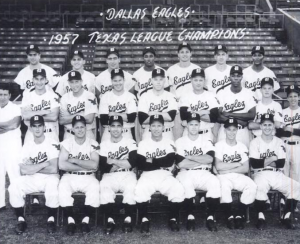

In ’55 Parker sought out Carl Hubbell [31] and was given a shot as a manager in the New York Giants’ system. He did well as a skipper for the El Dorado Oilers of the Cotton States League and then for the Danville Leafs of the Carolina League. Which led Parker back to the Texas League as skipper of the 1957 Dallas Eagles. Paced by Willie McCovey [32] and Ernie Broglio [33], the Eagles won 102 games and the pennant. (Parker collected one at-bat, his last in pro ball.) In 1958 the Giants tapped Parker as third-base coach for their first year in San Francisco. Twenty-two years after his debut in Detroit, Salty was back in the big leagues.

Parker coached in San Francisco for four years, followed by a year in Cleveland, a season scouting for the Pirates and three years as third-base coach for the Angels. And then in November 1966 his old Giants colleague Wes Westrum came calling and asked him to be part of the Mets’ brain trust.

Salty signed up, but the ’67 Mets were beyond his help. The combination of contract rumbles and his charges’ ineptitude sent Westrum around the bend — on Sept. 20 he called it quits with 11 games to go, telling reporters that “I’ve got one foot in the grave and the other on a banana peel.” (Hey, between that and his habitual postgame recap “Oh my God, wasn’t that awful?” the man was quotable.) Mets GM Bing Devine asked Parker to finish up the season — after 17 seasons of managing in the bushes, Salty would be making out a lineup card in the majors.

His tenure began with a doubleheader against the Astros. The Mets lost the first game convincingly [35], 8-0, as Jerry Koosman [36] (making his second-ever start) failed to retire a batter in the second. But they won the nightcap on a 10th-inning walkoff by Jerry Buchek [37], then took the next game on a three-hit shutout by rookie Tom Seaver [38]. After Seaver’s start, Jack Fisher [39] suggested Parker retire as the only winning manager in Mets history.

It was good advice — the Mets went 2-6 the rest of the year, leaving Parker with the 4-7 record as Mets manager he’d have forevermore. Which was fine with Salty. He understood that his first job as a big-league skipper wasn’t for keeps — when a Shea clubhouse attendant tried to move his things into the manager’s office he told him not to bother. It was an open secret in baseball that the Mets were eyeing Gil Hodges, then employed by the Senators, though they made noises about Alvin Dark, Harry “The Hat” Walker and Yogi Berra [40]. What were the Mets looking for in their next skipper? According to Devine, it was someone who’d bring the team a pennant. (At the time, this was considered hilarious.)

Parker said that if a club was looking for a coach he’d listen, and one was — for 1968 Salty signed on with the Astros as a member of Grady Hatton [41]‘s staff, kept serving under Walker, and in August 1972 he found himself interim manager again for a single day when Walker was fired and Leo Durocher [42] wasn’t on hand yet. (Salty won his only game as Houston skipper on a walkoff double by Cesar Cedeno [43].) He went on to coach again for the Angels, serve as a minor-league instructor for the Astros, and in 1976 took up his last managerial gig as skipper of the Cedar Rapids Giants. (He won a title, too.) That lasted a season, but Salty kept going, serving as an instructor for the Giants, the Mariners and finally for Houston’s Karl Young College League. He died in July 1992, less than three weeks after his 80th birthday.

And then there’s the story about the car. Remember the ’36 Tigers? The day Parker got called up, the team was invited to a banquet thrown by Chevrolet. The unhappy veterans wanted nothing to do with it, so pitcher Schoolboy Rowe [44] could only round up six or seven Tigers — one of them the just-recalled busher who didn’t know any better. At the banquet, the Tigers who’d bothered to show were told to turn over their plates — one of them was going home with a new car, courtesy of Chevrolet. That someone turned out to be Parker.

He’d discover that not every day in the big leagues included a free meal and a new car, but what a debut.