The 2023 Mets were expected to do big things. For the first 43 games of this season, they resisted those expectations. Then came last week: Games 44 through 48, each won by one run, each won after at some point trailing; each won as affirmation that the expectations were merited; each furnishing evidence that sometimes an experienced team needs not so much a youth movement as it does a youth shove. By Game 49, Tuesday night in Chicago, I was ready to accept a clunker. Tuesday night in Chicago, the Mets clunked [1]. It will happen from time to time, even to a club that’s lately had you looking up rather than feeling down.

The 1980 Mets were expected to do nothing. For the first 27 games of their season, they resembled those expectations. Then, for another 18 games, they improved in fits and starts, showing just enough progress on their good nights to leave you deciding the bad nights were no worse than exceptions to the new rule. In Game 45, Pat Zachry and Neil Allen together dueled Jim Kaat of the Cardinals for nine innings at Shea. Kaat was 41 at the time. He scattered six hits and gave up no runs before extras kicked in. Zachry had a two-hit shutout going over seven before giving way to a pinch-hitter. Neil Allen took over and retired his first six Redbirds. Alas, Ken Reitz led off the tenth with a homer, Kaat returned to the mound with a 1-0 lead, withstood a Doug Flynn infield single, and went all the way for the win.

Seventeen-year-old me was prone to processing this sort of outcome as evidence of progress rather than a serious setback. Sure enough, my faith in my 19-26 Mets was about to be rewarded with one of the best week-and-change periods I’ve ever experienced as a fan. It wasn’t just that the Mets went on to win eight of their next ten, it was how they did it. This was the year of the Magic is Back advertising and the week and change ahead turned the wishful thinking motto from punchline to way of life.

The Mets were in the midst of a long homestand. The Cardinals would be followed into town by the defending world champion Pirates, the perennially dangerous Dodgers, and their northern neighbors the Giants. In each of these series, starting with the last game against St. Louis — Game 46 — and running through the middle game against San Francisco — Game 55 — the Mets would stun an opponent by scoring the winning run in their final turn at bat. We didn’t say “walkoff” then, but that’s what was going on: four walkoff wins amid eight wins overall. The Mets kept walking it off, in 21st century parlance, each such finale more stunning than the one before, right through the last one, which still ranks as one of the most stunning results in Metropolitan annals.

That, on June 14, 1980, was the Steve Henderson Game, referenced and remarked upon myriad times since the inception of this blog in 2005. The Mets trailed, 4-0, before ever coming to bat that Saturday night. They were behind, 6-0, when it became an official game. It was 6-2 going to bottom of the ninth. There were two outs and Flynn on second when Lee Mazzilli stepped in versus Giant closer Greg Minton. Mazz singled Flynn home. Frank Taveras walked. New acquisition Claudell Washington drove in Lee, moving Frankie to second. San Fran skipper Dave Bristol removed Minton and brought in Allen Ripley. Ripley’s first batter was Steve Henderson [2]. He was also his last. Henderson crushed a three-run homer over the right field fence, into the Mets’ bullpen, directly to Tom Hausman’s glove. The Mets won, 7-6. The crowd, which wasn’t going anywhere once it absorbed what it had just witnessed, and Henderson, who had retreated to the clubhouse after accepting his teammates’ congratulations, together pretty much invented the Shea Stadium curtain call on the spot. Everybody just kept cheering. They wouldn’t leave until Hendu re-emerged to acknowledge their appreciation. Mets fans who were 17 in 1980 still get chills reliving it in 2023.

A week earlier, when those Mets were getting the hang of upsetting apple carts, their manager, Joe Torre, was dismissive of the leitmotif of the moment: “Magic?” he scoffed to reporters. “I’ve told you all before that’s just public relations.” Now, with Henderson having juiced everybody in attendance to levels of frenzy not felt in Flushing since 1973, Joe from Brooklyn allowed, “It’s really revving people up. Nobody left the park, even when they’re behind by six runs.” Indeed, the next day, nobody could stay away from the park. Not only did the Mets sell every available seat, they had to turn away approximately 6,000 potential customers.

That’s what it’s like when your team picks the right moment to come together and define itself for the better. I’m partial to it happening right around this spot on the schedule, more or less where we are and where we’ve just been in 2023.

In 1969, it was Game 42, coinciding with late-May/early June trip in from the California teams, one being the expansion Padres, the other two being those expatriate New Yorkers, the Giants and Dodgers, who had bullied the actual baby Mets on the reg since 1962. The Mets winning dramatically and consistently against anybody to pull themselves over .500 for good would have been uplifting. That the Mets rocketed toward the heavens at the expense of that pair of tormentors (who’d abandoned nearby boroughs, to boot) made the elevation exponentially sweeter. An eleven-game winning streak and so much more was about to unfurl.

In 1990, the Mets sagged so much for 47 games that it cost the only manager since Gil Hodges to lead them to a world championship his job. Davey Johnson was shown the door at 20-22. Bud Harrelson took over and wasn’t doing a whole lot better guiding what was supposed to be a perennial contender until the eleventh inning of Game 48, when a benchwarmer named Tom O’Malley (batting .091) took Expos reliever Dale Mohorcic over Shea’s center field fence. It was as if the Mets of the 1980s materialized for a curtain call, back in a pennant race on the cusp of what shaped up as one more glorious — or at least quasi-glorious — summer. The team that had been 21-26 entering play on June 5 would be 48-31 coming out of the All-Star break.

In 1980, it was Game 46 when everything beautiful and Magical kicked in. In 2023, it was Game 44. May becoming June. Spring becoming summer. Warm enough to sleep with the window open. Cool enough to keep the air conditioning off. You wake up to a soft breeze, and you’re excited about the Mets, and it will take more than one bump in the road to jar you from the journey to which you’ve emotionally committed.

Yet you won’t win them all. Game 49 in Chicago in 2023 provided a fresh batch of proof. It was a splendid night for Cubs, mostly. For a journeyman starter named Drew Smyly, who threw five smooth innings to climb to 5-1, with an ERA under three. For a former Met pitching prospect named Michael Fulmer. We traded Fulmer for Yoenis Cespedes in 2015 and it was totally worth it, even when the kid we sent to Detroit won the AL Rookie of the Year in 2016 and made the All-Star team in 2017 and seemed to grip a future that would have fit in with what had penciled in for deGrom, Syndergaard, et al., before injuries led him to his role as a 2023 mopup man…which is what he was consigned to filling when at last facing his original organization for the first time. Michael pitched a scoreless ninth in defense of a five-run lead. And for a breakout slugger named Christopher Morel, who seems partial to drawing cat whiskers on his face with eye black. Morel played 113 games as a rookie in 2022 and socked 16 homers. He’s been up with the big club in 2023 for a dozen games and, against Stephen Nogosek on Tuesday night, blasted his ninth home run of the year. Produce like that for a few more dozen games, and you can open for Kiss.

To take nothing away from Morel or Seiya Suzuki or Matt Mervis (the latter two of whom homered off Met starter and loser Tylor Megill), the bat that shouted out loudest in this game belonged to Pete Alonso [3]. It’s not so much that his fourth-inning home run off Smyly cut the Cubs’ lead to 4-1, or that the shot traveled 434 feet from home plate and several rows up into Wrigley Field’s left-center field bleachers, or even that Pete had now increased his major league-leading total to 18, a pace that places him en route to 60. When Pete burst onto the scene in 2019, I tracked his rate vis-à-vis the Met home run record carefully. He shattered that baby (41, established by Todd Hundley in 1996 and equaled by Carlos Beltran in 2006) with little sweat expended and raised it to 53. Once my giddiness from his rookie campaign settled down, I figured that would be the last time I tracked Pete’s homers for season record comparisons, because yo, no way was he going to hit that many again. But for the hell of it, I just looked up when Pete hit his 18th in ’19. It was Game 55, or six games later than this year.

Yet even that’s not the Pete pace I’m thinking of today. What’s really got my attention is that those Magical 1980 Mets, notorious for their power-eschewing offense, didn’t hit their eighteenth home run — I mean collectively — until their 63rd game of the season, and it required the acquisition of Claudell Washington in June, and Washington hitting three home runs on June 22, to get them that many that late in the season. Holy crap, Pete is outhomering the entirety of the 1980 Mets, who, the Daily News enjoyed reminding its readers that summer, were having a hard time matching Roger Maris’s rate from his 61 in ’61; the joke was on them — the 1980 Mets hit exactly 61 home runs.

Steve Henderson’s home run in Game 55, on June 14, was the Mets’ thirteenth and his first of the season. He’d been batting for average (.340), but was a little shy on a particular variety of extra-base hit. That was OK, Steve assured the media. “Home runs,” he said, “are overrated.”

Except when they catapult you from behind and make you recall fondly what eventually crashed into a 67-95 record, which is how the Mets finished 1980, but details, details. I don’t know what the ultimate details of 2023 will be. I do know that despite losing, 7-2, in Chicago and snapping their sensational five-game winning streak achieved at Citi Field, the tenor of this season has been altered for the better. I can’t swear something won’t definitively detract from this current mood over the next 113 games, but what the Mets did versus the Rays and the Guardians and how they did it is likely gonna stay with me when somebody someday mentions this year. I primarily remember 1980 not for the 95 losses in all nor for the frankly pathetic sum of 61 home runs from April until October — nor even for the rather flat performance the Mets turned in during Game 56 in front of a sold-out Shea on June 15, losing, 3-0 to Bob Knepper and the Giants, which is what Game 49 Tuesday night at Wrigley evoked within the realm of raucousness pressing pause. I remember the Magic of the week and change before that loss, never mind the losses to come. I remember the change. I swear, 43 years later, it’s still rattling around in the pockets of my Mets consciousness.

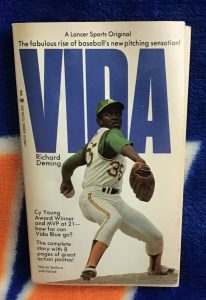

You don’t forget a name like Vida Blue, and you don’t forget a pitcher like Vida Blue. The only Vida Blues I’m aware of were Vida and his father, Vida, Sr. I read up on Vida voraciously when I was nine years old because I followed his ascent breathlessly when I was eight. The lefty for Oakland so mesmerized fans of all ages in 1971, that a paperback book was commissioned for 1972. It was called Vida, written by Richard Deming. Its cover price was 95 cents. I don’t know how much it was listed for when I came across it at a school sale in third grade, shortly after it was published. I do know I snapped it up and read it immediately. It is because of Vida, I know that the phenom who went 24-8 with an ERA of 1.82 was a junior. I know from Vida that Vida, Jr., lost Vida, Sr., in high school.

Vida ran up the porch steps whistling. the front door opened and the whistle died when he saw his mother standing there with his sisters and his brother crowded behind her. He came to a dead halt.

After a moment he said quietly, “Dad?”

Sallie Blue nodded, her eyes brimming with tears.

“Dead?” he asked.

She nodded again, and now the tears began to flow. Then she was sobbing against his shoulder and he was patting her back as though he were the parent and she the child.

“Now, Junior, you’re the man of the house,” she said through her tears.

Broke my heart to read that when I was nine. Breaks my heart to revisit it again. When Vida, Jr., died earlier this month [5] at the age of 73, not long after he’d taken the field in Oakland for a 50th-anniversary reunion of the 1973 world champs during the Mets’ visit there, I remembered that scene, as well as another from the paperback (a book I regrettably discarded in my late twenties but have again today, thanks to the thoughtfulness of a friend who replaced it for me in my early fifties). By this stage in Blue’s story, the southpaw is levitating toward the top of the baseball world, maybe the world at large, and A’s owner Charlie O. Finley comes to him with what Finley has convinced himself is a brilliant idea.

He suggested that Vida have his name changed legally to Vida True Blue, and they would then thereafter use his middle name.

“We’ll take the name Blue off your uniform and have them use True,” Finley said. “And I’ll tell the broadcast boys to call you True Blue.”

As a nine-year-old baseball fan, I was aware of Charlie Finley and wasn’t impressed. This anecdote sealed my disdain. “The broadcast boys…” Yeesh. Vida, Jr., explained to Finley that he was honoring his father’s memory every time he pitched (eventually pitching with VIDA on the back of his jersey rather than BLUE). Finley didn’t push the matter, but did have the Coliseum scoreboard announce before Vida’s next start that “True Blue” would be pitching soon, get your tickets today. Vida got the owner to stop with the shenanigans, “polite” about it, according to Deming, but “quite definite. He did not want to be called True Blue, ever. This time Finley dropped the idea permanently.” Later, according to the author, Vida asked teammates, “If he think it’s such a great name, why doesn’t he call himself True O. Finley?”

Maybe that exchange is why, when the Mets played the A’s in the 1973 World Series, I was all for beating Ken Holtzman and Catfish Hunter, but didn’t take any extra relish in doing damage to Vida Blue. Not that I minded that we won his two starts, in Games Two and Five, but Vida Blue was one of a kind in 1971, and that sort of currency, like a home run in the first third of an otherwise woebegone season, will maintain its place in a person’s heart. When the A’s traded Blue to the Giants in 1978, I was excited to see the lefty make the All-Star team in the National League the way he’d made it three times in the AL and would make it twice more in the NL, including 1980. I wasn’t too happy Blue stanched our Magic momentum on June 13, 1980, defeating the Mets, 3-1 — nor did I care for his postgame quote after he bested Ray Burris that “I didn’t encounter any Mets magic” on Hendu’s Eve — but he was still Vida Blue, the one and only, and here he was, still pitching well when I was 17 after dominating baseball when I was eight. That’s more than half a lifetime at that age.

My final memory of Vida Blue as an active player comes from five years later, right around this time of year in 1985. I was 22. He was 35 and in his second go-round with the Giants, but seemed ancient after an arrest and suspension for cocaine possession sidelined him for all of 1984. The Mets were at Candlestick Park on May 30, Game 52. Doc Gooden was on the mound, just entering that phase of ’85 when he’d be both unbeatable and untouchable. Marty Noble of Newsday, who recognized an angle when he saw one sitting on the opposing team’s bench, sought out Blue to comment on what Gooden was doing. Dwight had just gone the distance, allowing only a run and six hits while striking out fourteen in the Mets’ 2-1 victory over the already hapless Giants.

“Impressive, very impressive.,” Blue said. “The strikeouts were something. What did he have? Fourteen? That’s a lot. But the thing that really impressed me is when he got them — right when it counted most. He closed the door on us when we had a chance in the sixth.”

Yes, in the sixth, Dwight was very much Doc. San Francisco had runners on second and third, with nobody out. But Gooden simply set to operating, popping up ex-Met Gary Rajsich, then striking out Jeffrey Leonard and Chris Brown to get out of what passed for a jam.

“That was the way I used to pitch,” Blue said with touches of whimsy and envy in his tone. “I wasn’t thinking about it much until that situation came up. but I watched him and he tuned up when he had to. That’s what I used to do.”

Blue would finish his big league career in 1986 with 209 wins, never quite the 1971 version of Vida again, but Doc, with an even more phenomenal line to his signature season, was never quite as much Doc again after 1985. How do you stay at the top of the world? If the answer was attainable, it would be permanently crowded up there. Doc’s win over Vida’s team put his record at 7-3, with his ERA dipping to 1.79. You couldn’t be sure 24-4 and 1.53 was where Gooden was headed, but maybe it took one to know one. In talking to Noble at the end of May 1985, Blue labeled his own 1971 “my Gooden year. I had games like this that year.”

That statement was absolutely True.