As noted often in this space, I consider listening to Gary Cohen talking Mets baseball a perk of being a Mets fan. Listening to him on Saturday, both while sitting in the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room as he and his fellow inductees prepared for their big moment on the field, and then from the press box while he stood before the fans who gave him and Howie Rose the applause that have been building up for more than three decades apiece, represented a feast for my auditory senses. Little that Gary says goes in one ear and out the other. It zips its way to the brain, settles there, and gives me more than I counted on thinking about.

Two observations of Gary’s from Saturday stand out for me here on Monday.

1) In response to my fancy reportorial question — posed to the table full of Famers, answered by the announcers — about what really surprises a fully grown youngster who dreamed of making it to the big leagues and then actually did, whether via pitching or hitting or talking, Gary (after Howie spoke thoughtfully and knowingly about the rigors of travel) offered a layer of perspective he admitted to not having while spending all those days and nights in the Upper Deck.

“Going from being a fan to a broadcaster at the highest level in Major League Baseball, I think the thing that you learn very quickly is what extraordinary athletes these guys are. You know, it’s very easy for people to sit in the stands and watch major league baseball players fail, and it’s a game of failure, but even the last guy on a major league roster is an extraordinarily talented athlete, and just standing behind a batting cage and watching the hand-eye coordination involved, again with the lowliest of major leaguers, is so far beyond the ken of those of us who can’t do those things, I think it makes you appreciate just what this game is, and how difficult it is to play, and how monumentally talented all of these players are. To me, that was the most eye-opening piece.”

2) During the speech itself, Gary wished to single out as best he could “so many people who have helped me on my way to this moment,” starting out where one might expect a person might on a day such as this:

“My mom, who passed away earlier this year. She was a Giants fan until the day Willie Mays became a Met. Then she became a Mets fan.”

It’s worth noting that by the time Mrs. Cohen switched allegiances, her son was already ensconced upstairs at Shea. His idol down below was Bud Harrelson. His idol on his transistor radio was Bob Murphy. We know whose path Gary Cohen followed to the big leagues. The rest of us don’t carve out any kind of road to the big leagues beyond going to games or following them over whichever devices are most contemporary. We’re just thrilled to be along for the ride from however far we attempt to breathe it in.

I’m thinking of all this following the weekend when Gary and Howie, in the company of Al Leiter and Howard Johnson, received their due in the Hall of Fame [1], because of the way baseball goes on. Baseball went on Sunday, the day after those exquisite ceremonies. The Mets played the Blue Jays again, and lost to the Blue Jays again [2]. A fan would have to exercise Cohenesque restraint to not say out loud that the result sucked. But it did. It doesn’t mean the players who came out on the short end three days in a row sucked. They are indeed extraordinary athletes, right down to the last guy on the roster. But sometimes the combined product of the collective efforts of the extraordinary athletes in whom you threw in your lot for life before you turned ten kind of sucks. The Mets lost on consecutive days by scores of 3-0, 2-1 and 6-4. Something wasn’t functioning as well as it could have.

On Sunday, it was the starting pitching, which had been outstanding at Citi Field all week, and sublime all season when it fell to Kodai Senga at home. The secret ingredient to Senga’s Citi success was he was him being the most well-rested cuss in Flushing since whichever mystery member of the maintenance staff who was called on to mop up that perennial puddle in Promenade behind home plate chose to maintain instead his nap. I’m referring to the puddle that I swear just sat there unattended for the bulk of the 2010s, and I’ll have to check on it next time I’m in the neighborhood of Section 514. Kodai, who’s absorbed opponents’ swings and misses regularly during Citi starts, didn’t pitch on four days’ rest in Japan, so the Mets didn’t push him. Yet he was so good starting out this homestand against the Phillies, and the pieces don’t really exist for a six-man rotation that would keep him on extended rest into perpetuity. Thus, Buck pushed him. The lack of rest pushed back. Senga didn’t make it out of the third. The bullpen got leaned on. Much of the relief corps withstood the pressure of having to go a six-and-a-third. Dominic Leone, who gave up the deciding two-run homer to Brandon Belt in the seventh, didn’t.

It was also the sporadic offense not helping matters on Sunday. Huzzahs for four home runs hit by Mets. Raspberries for nobody being on base for any of them, nor any other episode of scoring by any Met that didn’t involve a solo home run. Do you know what always happens when the Mets hit four solo home runs and that accounts for the totality of their scoring? They lose. That’s not an exaggeration. The Mets have launched four solo home runs five times in their history without figuring any other way to put up a run, and every time they have lost [3]. Solo home runs can be very handy. They can also be fool’s gold if you think they’re all you need to thrive.

Still, good for Tommy Pham going deep twice at Citi Field, the first two times he’s done it at home as a Met (it would have been sweet to have followed up the Hall of Fame with the Haul of Pham). Good for Starling Marte flexing his muscles once again. And really good for Pete Alonso taking over the all-time lead from Lucas Duda for most regular-season home runs hit by a Met in the ballpark that’s been open since 2009 and that by 2010 [4] still seemed like Death Valley — or at least Locust Valley — when it came to slugging. Fences have come in a few times since we bemoaned how hard it was for anybody to hit a ball out of Citi Field. It got easier if not easy. On Sunday, Pete needed a replay review that shrugged when asked about orange lines and black backdrops. I didn’t think Pete’s 72nd lifetime Citi dinger left the yard once I watched it bouncing up and not quite over the wall in left a few slow-motion times. But the Blue Jays didn’t ask me to do the reviewing. Pete’s reaction to setting the record was that it was “sick,” which even Kodai Senga doesn’t need a translator to know means swell.

Pete’s bounce above the orange line, wherever it did or didn’t tick, might have been the only bounce or bouncelike element that went the Mets’ way on Sunday. Pham wasn’t as much of a fielder as he was a slugger, not swiftly scooping up an errant Francisco Alvarez throw on a stolen base attempt that instantly became a run. Alvarez might have tagged the runner, Matt Chapman, a nanosecond before any of his toes touched the plate, but the angle that would have proved it conclusively didn’t prove anything. Besides, Chapman felt safe, and go challenge that. Marte also hit a triple that turned into a ground-rule double early on, auguring One of Those Days when the Mets really could have used the different kind.

Again, though, they’re all talented and capable, which makes it that much more aggravating when the talent and capability checks in at .500 after 60 games, just as it checked in at .500 after 54 games…and 50 games…and 46 games…and 34 games…and 32 games…and it’s been One of Those Seasons, hasn’t it?

Yet there have been so many seasons when we, the fans in the stands or on the couches in front of the TV or in the car with the radio tuned to 880, know a stop & start .500 season with talented players and a forgiving playoff qualification format beats the lesser alternative. The lesser alternative, whether we experienced it directly or feel it pulsate within our DNA, could be found in 1962 and 1963 and 1967 and 1978 and 2017, five losing years picked not at random. In a particular order…

2017: It’s the year after a Wild Card season when the Mets have opted to go in a different direction: down. Let’s hope 2023 doesn’t ultimately resemble that year (70-92) too closely. Still, 2017 did introduce us to a recurring supporting character in our ongoing story, a catcher from Puerto Rico named Tomás Nido [5], a catcher whose first name I always stop to make sure I accent properly when it comes to his “á”. It doesn’t look like that will be a continuing concern for this correspondent, as Nido has been designated for assignment to clear space for the return of Omar Narvaez from the injured list. Narvaez the veteran, Alvarez the phenom; no room at the two-catcher inn any longer for the second-longest tenured Met who never grew into a consistent hitter at the major league level, but, as Gary Cohen reminded us, that doesn’t mean he wasn’t any good. He had a few big hits across his seven mostly partial season in the bigs, and his catching was big league-caliber. Tomás was kind of a throwback — the career backup receiver who could be depended on in a pinch by one organization for a very long time. It’s not what a kid dreams of growing up to be, but sometimes you get that far, you get a little farther. By the end of 2022, Nido was the starting catcher for a playoff team in a pinch. Should we cross paths with him in another uniform, I will be sincere in referring to him as an Old Friend™. [6]

[6]

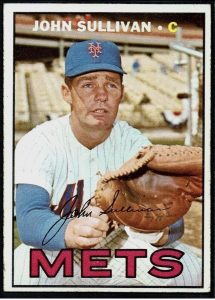

1967: It’s the year every Mets fan should recognize as the season that launched George Thomas Seaver on his way to every Hall of Fame in sight: the one in Flushing, the one in Cooperstown, the one in Cincinnati, even (sigh). Seaver probably launched himself, but, as those who joined him in official Met immortality Saturday emphasized, nobody gets where he’s going by himself. Tom himself made a point of mentioning the most distinguished catchers with whom he’d worked when he accepted his plaque Upstate in 1992: Jerry Grote, Johnny Bench, Carlton Fisk. Also catching Seaver’s sensational pitches when Tom was 22, besides young Grote, was a journeyman named John Sullivan [7]. John’s journey, which ended in the broadest sense when he died at age 82 last week, wound through the 1966 Rule 5 draft from which the Mets selected him and thus had to keep him around all of ’67. Sullivan gave the Mets 65 games of catching, including seven in service to the rookie righty from Fresno. With Sullivan catching, Seaver posted an ERA of 2.55, the lowest Tom registered in tandem with any catcher in his freshman campaign. The very first time Tom totaled double-digit strikeouts (12), it was Sullivan behind the plate framing and cradling every last one of them. John spent only a year in what we’ll call the Nido role in New York. He’d work as the bullpen coach for the Blue Jays long before we had to worry about them on the Mets’ schedule, through the ’80s and into the ’90s, and enjoy a Hall of Fame-worthy moment himself. When Joe Carter hit the home run that won the 1993 World Series for the Jays, it was Sullivan who retrieved the historic horsehide and, though officials from Cooperstown came looking for it, held onto it long enough to hand it to Carter [8]. “Touch ’em all, Joe,” John was essentially saying to Joe about all 108 stitches on that baseball. Few of us will ever be part of a bigger moment. [9]

[9]

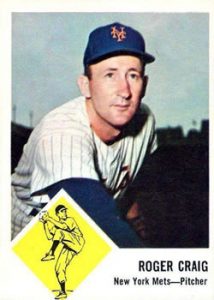

1962 and 1963: These years speak for themselves. Rather, the announcers who set the precedent for Gary and Howie, spoke to us about them in case we missed them. Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner filled us slightly younger kids in on the wonders of the Polo Grounds seasons, the legend of Casey Stengel and the players who would be mythical figures if they weren’t real. Thanks to their storytelling, I learned who Roger Craig [10] was. I learned Roger Craig, righthander from North Carolina, was a seminal figure. I learned Roger Craig was the Mets’ very first starting pitcher. I learned Roger Craig pitched without much run support. I learned that yes, Roger Craig lost a lot of ballgames, but it was also drummed into me at an early age that to lose 20+ games in a single season (Craig lost 24 during the first Met year and 22 the second), you have to be pretty good to get the ball and keep going out there and giving it another try. Roger Craig, who died this weekend at 93, helped the Dodgers in Brooklyn and Los Angeles to world championships before there were Mets; as with securing the services of Gil Hodges, Don Zimmer, Clem Labine and Charlie Neal, the new club in New York saw Craig’s presence in Manhattan as a potential lure to Bum-bereft Brooklynites unsure about crossing certain geographic and psychic bridges into the land of Metsdom. Roger also helped the Cardinals to a world championship once the Mets had mercy on his competitive soul and traded him to a contender. He threw more than 230 innings in consecutive seasons as a Met, all while bearing the brunt of just about everything going wrong. Photos from that period suggested a gentleman trying hard not to appear beleaguered. Interviews conducted by Kiner of Craig conveyed a person who’d survived the ordeal of 40-120 and 51-111 just fine. Roger made himself and his recollections available to Ralph plenty during his years as a coach and a manager at various National League stops, right up to his leading the Giants to the World Series in 1989. Our first pitcher visited Citi Field in 2012 on the exact fiftieth anniversary of our first game: April 11 (welcomed home despite teaching Mike Scott the split-finger fastball). On that date in 1962, Roger and the Mets lost, 11-4. On that date in 2012, with Roger Craig tossing out the ceremonial first pitch, Johan Santana and the Mets lost, 4-0. You wouldn’t accuse either of those men of not being a pretty good pitcher.

Roger, an Original Met if ever there’s been one, was the longest-living Met when he passed away. The oldest among our guys now? Gary Cohen’s mom’s favorite player, the Say Hey Kid. Willie Mays, at 92, tops the list, as he tops so many of them.

1978: Mike Bruhert [12], I’m pleased to announce, is still alive. I’d be even more pleased to announce that I ran into him on the LIRR platform at Jamaica Saturday night after Hall of Fame Day at Citi Field. There was a delay born of a signal problem, and there was a lot of standing around, and then, as if from the cornfield, appeared a man wearing a BRUHERT 26 Mets jersey, honoring one of the Mets’ most electrifying starters — actually from Queens! — from the only electrifying portion of the 1978 season, the first part, when the Mets briefly topped the NL East standings and stayed close to .500 until Memorial Day. I don’t have to look any of that up. I’ve reveled in that too-brief spurt of success for 45 years now. I was 15 then. It made an impression. Bruhert in the rotation and Mardie Cornejo in the bullpen were the big surprises in the big push to respectability following the misery of Seaver’s exit and the rest of 1977. The entire enterprise faded (last place awaited in ’78, just like it had in ’77, just as it would in ’79), but for a few weeks there, it was very exciting and very gratifying and if I had bumped into somebody wearing a BRUHERT 26 jersey then, I would have plotzed. Running into somebody wearing one on Saturday had almost the same effect on me. Never mind that I had just finished being a media representative Saturday afternoon, asking professional-sounding questions at a press conference, and casually ambling along the field before the Hall of Fame ceremonies, and taking notes in the press box without uttering a yea or nay. By Saturday night, I was just me again, a fan who saw BRUHERT 26 and had to ask, after ten minutes of railroad delay made all of us static and therefore readily accessible, “excuse me are you…?”

He wasn’t. Not quite. It was Mike Bruhert’s brother, Jim. It was all I could do to not respond, “OHMIGOD, YOU KNOW MIKE BRUHERT!” I mean, Mike Bruhert’s brother, Jim, is a person in his own right. I should have been delighted to meet him and left it at that. Yet he was honoring his brother, and how do you not follow up on a jersey you simply don’t see every day? Jim was kind enough to tell me he had the jersey made up in 2008, which explains why it carries a drop shadow and a FINAL SEASON patch. Jim, who had just gone to the game with his family, patiently explained between my babbles and burbles that I was the second person to ask him if he was Mike Bruhert. “Only the second?” I thought.

I’m not looking up Mike Bruhert’s career numbers. I don’t have to. He was a Met when I was a kid, which means he remains larger than life; larger than a delay at Jamaica, as aggravating as that can be. Like Gary Cohen said, all these guys are monumentally talented, though when I was 15, I’d like to believe I understood that already.