Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Under a big ol’ sky

Out in a field of green

There’s gotta be something

Left for us to believe

—Tom Petty, “Kings Highway”

It’s Opening Day 2002 at sunny Shea Stadium. The Mets have been reconfigured to dominate after they deteriorated in 2001. It won’t work out that way, but we don’t know that yet. Besides, it doesn’t much matter that the cast has been so thoroughly shuffled from the year before. On Opening Day, your team is YOUR team. Just let somebody try to steal your sunshine.

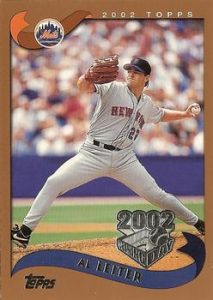

On sunny Opening Day 2002, Al Leiter is OUR starting pitcher. On many days between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2004, Al Leiter was our starting pitcher. The only thing Al Leiter ever did as a Met (other than triple) was starting-pitch: 213 games, 213 starts. That’s more starts as a Met pitcher without a single pitch thrown in relief than anybody else. Jacob deGrom is second by more than a conceivable season’s worth of starts — a real season, not whatever 2020 is shaping up as on corporate drawing boards.

We didn’t coordinate with one another, but Al Leiter is also the career leader in starting games I’ve attended, and I’ve been attending games since 1973. Al and I were by no means a bad pairing, no matter how intuitively unlikely it seems in retrospect that we’d get together as frequently as we did. We all believe that when we buy a ticket to a ballgame, the fine print subjects us to a steady uninspiring stream of Trachsels and Nieses. I’ve had my share of those, too. Plenty of Kevin Appier the one year he was here. A load of Bobby Jones, a dash of Randy Jones, a pinch of Pete Smith for mediocre measure. I’m not convinced I won’t see Mike Pelfrey slog through six innings the next game I go to, and he hasn’t been on the Mets since 2012. Go to enough games, you’ll see just about everybody take a start or ten. Go to more than enough games, though, specifically between 1998 and 2004, and you’ll get your Leiter on repeatedly.

There was little hint of phenomenon to it, no boasting within your social circles that you hit the Al Leiter game last week, no future posting for posterity on Facebook that you were a part of Leitermania, here’s a picture of my ticket stub! But if Al Leiter was a notch below the perceived glamour of acedom, he hovered discernible cuts above the middle of the pack. Sometimes an ace is an inherently imposing mound presence. Sometimes he’s just the best guy you’ve got handy. When somebody whose credentials glittered a little more brightly than his was acquired in some ambitious offseason, Al Leiter would be courteously consigned to 1A status — still conferred the organizational respect he’d earned, yet no longer automatically tabbed as the first choice to start a season or a series, assuming there was ample opportunity to line your pitching up according to preference.

When nobody better was around, or you simply had to win the next game in front of you, you could do a lot worse than Al Leiter. In contemplating the Metsian legacy of the lefty who was never exactly “my guy” despite my seeing him so regularly, I’m reminded of a tribute to Tom Petty that I read in the wake of the singer’s death in 2017. It referred to Petty’s music as good for the middle of a weekday afternoon, or something to that effect. I don’t recall the exact phrase or precisely what the author meant, but I liked the description and I think I got it. I was by no means the biggest Tom Petty fan, but I admired how he used his repertoire, how he threw himself into his game, and how he left me feeling better for having experienced him doing what he did anytime I’d hear him do it.

Thirty-seven regular-season games at Shea Stadium Al Leiter was my starting pitcher, plus twice in the playoffs and, to be rotationally retentive about it, once as an opponent. I don’t ever remember thinking in advance, “Leiter? Not again.” Nor, probably, did I think, “Oh boy, Leiter!” It was more like, “Al Leiter…all right, let’s go…” The games could get edgy when Bobby Valentine was managing, but a bit of the edge was taken off knowing Al Leiter was starting. His near-constant presence was comforting. That was where my head was at on Opening Day 2002, just as it was more than two-dozen times before. Standing and applauding in the right field boxes, it was exciting to welcome Alomar and Vaughn, welcome back Burnitz and Cedeño, value as ever Piazza and Alfonzo. But when we got to “pitching and batting ninth, warming up in the bullpen…”

Al Leiter. All right. Let’s go.

In transactional terms, Al Leiter became a Met because the Florida Marlins were dumping their champion players left and right following their 1997 world conquest. But really, Al Leiter became a Met because Al Leiter was always supposed to be a Met. Before Todd Frazier invented being from New Jersey, Al Leiter was from New Jersey — the same town as Todd — and he grew up a Mets fan, old enough to tell us that as a lad he witnessed the Mets’ 1969 flag run up the center field pole on Opening Day 1970. Depending on the interview he was giving, he also seemed to grow up not immune to the charms of other teams within driving distance of Toms River, but fealty to the Metropolitan cause fit his story and personality most snugly.

Two starts into his Met tenure, he looked the part of prominent Met pitcher. Not that he was as graceful as Seaver or as overpowering as Gooden, but he was as preoccupied with the Mets winning as any of us. Leiter probably wanted to win for Leiter, as starting pitchers are prone to do, but you couldn’t wipe the familiar concern off his face. He grimaced. He grunted. He gritted. He looked like us. His look certainly got the attention of my wife, who had the game on before I came home on April 7, 1998. The Mets were at Wrigley that afternoon and Stephanie, usually a passive consumer of baseball telecasts, wanted to know what the deal was with this guy with the face.

That face was the deal. He was the cat of a thousand expressions. That’s what we call our kitty Avery. The concept originated with our watching eternally expressive Al Leiter. He was always doing something that fascinated us, not the least of which was pitching effectively. Leiter steadily put the “1” in “1A” as 1998 got rolling, emerging as first among a staff of approximate equals, missing the All-Star team only because of an ill-timed knee injury in late June. While the Mets mostly melted down around him, Leiter stayed strong in September. Al finished his first Flushing year 17-6 with an ERA of 2.47 and garnered token Cy Young support, the first Met to be so acknowledged in four years. You couldn’t run it up the center field pole, but it was surely worth saluting.

Leiter never again had quite as brilliant a campaign for the Mets as he did in his initial one, but he never had a genuinely bad season over his remaining six. Three times he opened the season. Once he opened a World Series — and tried desperately to keep the same World Series going. Al Leiter being entrusted with the ninth inning and all its inherent implications in Game Five of 2000 and not getting all the way out of it versus I forget who never hung around his or Bobby Valentine’s neck quite the way a close facsimile from 2015 sticks to the respective shoes of Matt Harvey and Terry Collins. Al is remembered better for coming through than coming apart. He stopped a potentially lethal losing streak down the stretch in ’99; clinched a playoff spot via masterful two-hitter less than a week later; and held the Mets aloft for much of what was to become known as the Todd Pratt game less than a week after that.

Leiter’s one truly godawful postseason outing, when, on short rest, he didn’t retire a single Brave in the first inning of ultimately decisive Game Six of the 1999 NLCS, is relatively obscure in the scheme of Al’s career. In the annals of abysmal first innings proffered by titular Met southpaw aces at the worst imaginable juncture, it doesn’t hold a candle in the realm of public perception to T#m Gl@v!ne’s least finest hour, which took place somewhere between 1:10 and 1:30, September 30, 2007. For that matter, Leiter’s horrifying first inning from the night of October 19, 1999, at Turner Field (0 IP, 2 H, 1 BB, 2 HBP, 5 ER) is obscured in common memory by the work of another veteran lefty, Kenny Rogers, ten innings later.

Maybe it was because locally sourced Leiter put his heart into every start he took as a Met. And his face, which you couldn’t miss. Plus he was always good for a detailed explanation of why he may not have won on a given evening and what he (along with his teammates) could have done more ably. Al’s starts could feel like struggles even when he was shutting down opponents, which is why his victories registered as triumphs of the Mets fan soul. He seemed properly bothered by everything that went wrong when anything went wrong.

Fortunately, plenty went right for seven seasons, so even with the occasional rough patches on the mound, Al Leiter remained OUR starter in generally good standing pretty much to the end of his time as a Met. His last start for us — and for me — came at Shea on October 2, 2004, a Saturday night against the Expos, the last game that franchise won under its original name. Omar Minaya, Montreal’s former GM, had just been hired to do the same job for the Mets. It was obvious Minaya’s Mets were going to have to put the current futile era behind them ASAP.

That meant the imminent end of Al Leiter, pending free agent, who had two Met eras under his belt (three counting his childhood allegiance to Seaver and Koosman). Before Opening Day 2002, Al was right in the middle of every big series the Mets had contested for four mostly successful, uniformly scintillating years. Those Mets of 1998-2001 were kind of a 1A operation themselves. When somebody better-credentialed was on hand, the Mets took a back seat. When nobody better was around, you could do worse.

The Mets did worse in 2002, 2003 and 2004, lacking for big series altogether after dismal reality set in, but on Opening Day 2002, we didn’t know that further deterioration rather than a surge toward dominance was in store. We just knew Al Leiter would be starting. We just knew, as of April 1, 2002, that Al Leiter was always starting…OK, often starting. But he was on the mound a lot, giving us his all, and it most always gave us a reason to be reasonably confident that we might win this game. Like on Opening Day 2002, a 6-2 middle-of-a-weekday afternoon Mets win in which Leiter pitched six innings and gave up no runs. Like so many other days. Leiter won 95 games as a Met, sixth-most in club history. That implosion in Atlanta notwithstanding, he was usually money in the postseason for us, even if he never pulled down a W. It was telling that we were in the postseason enough during Leiter’s first era that he could mount an October sample size worthy of measurement. He made seven starts, six of them undeniably quality.

In 2005, the next Met era, Al Leiter was essentially replaced by Pedro Martinez. That was an ace you didn’t need to append an “A” to. He was an undisputed No. 1 pitcher, starting games that were destined to be billed as bona fide events all summer long. Time to move on. Time to get going. The first time Pedro started at Shea as a Met, on April 16 versus the Marlins, the joint jumped with anticipation. His mound opponent was his predecessor, now a Recidivist Fish, marking the fortieth and final time I saw him pitch in person. Martinez vs. Leiter. Giddily promising present vs. suddenly distant past. Pedro cheered wildly by a sellout crowd. Leiter booed obligatorily for what he wasn’t: for not being Pedro; for not being ours.

Al’s expression told me he got it.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

I had my own guy who seemed to pitch ‘a lot’ whenever I went, and that guy was Ed Lynch. I was always disappointed whenever he started these games, and usually he met my lowered expectations.

Only one Lynchie for me, a win in the Get Even For Last Year series vs. the Cubs, June 1985.

Ed Lynch was the last of the pre-Gooden era pitchers to stick around, lasting until the middle of the ’86 season. I was always kind of fond of him and felt bad that he didn’t last long enough to sample the champagne that October, although I understood why he was let go at that point.

[…] Face of the Franchise » […]