The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 24 February 2026 12:43 pm “Say, the new baseball season is coming.”

“Yeah, I guess it is. I’m not quite the diehard I used to be, but I’d like to catch up with what’s going with my favorite baseball team, the New York Mets.”

“In that case, I think it’s important that we establish some fundamentals about the Mets.”

“Fundamentals? Like what?”

“For example, every ballplayer on a ballclub has a very specific job, something the ballclub understands the ballplayer is best suited for.”

“Every ballplayer?”

“Every ballplayer. Even on the Mets.”

“Even on the Mets?”

“That’s right, even on the Mets.”

“So if I ask you about a ballplayer on the Mets, you can tell me who he is and what he does?”

A modest explainer, already in progress. “That’s correct. Go ahead and try me.”

“Who’s on first?”

“Polanco.”

“So Polanco’s a first baseman?”

“Not yet.”

“Who’s on third?”

“Bichette.”

“So Bichette’s a third baseman?”

“Not yet.”

“Who’s in left?”

“Soto.”

“So Soto’s a left fielder?”

“He has been. More recently he was in right.”

“I see, I think. Well, who’s in right?”

“I dunno.”

“I dunno is a peculiar name for a ballplayer, even on the Mets.”

“No, I’m telling you I dunno yet who’s gonna be the Mets’ right fielder.”

“Then how can you be so sure about the other positions I asked about?”

“Because they told me.”

“Who told you?”

“The Mets.”

“The Mets told you Polanco’s gonna be on first even though he’s not a first baseman, Bichette’s gonna be on third even though he’s not a third baseman, and Soto’s gonna be in left even though he’s not a left fielder.”

“But he has been.”

“Not lately, though?”

“No, Soto was a right fielder.”

“Soto was a right fielder?”

“Practically every day last year.”

“Soto was in right?”

“Right.”

“Wasn’t he on third?”

“That was a while back. Wright’s not around anymore.”

“So who was on third when Soto was in right?”

“Baty was on third, mostly. And sometime Vientos.”

“But Baty and Vientos aren’t on third now?”

“Nope.”

“So is it right to say they’re not around anymore?”

“No, they’re around.”

“Baty and Vientos are around?”

“Correct.”

“So what do they do if they’re not on third?”

“I dunno.”

“I thought you said I dunno is in right.”

“What I said is I dunno who’s in right.”

“Which means it’s not Soto.”

“Right.”

“Right as in correct?”

“Right.”

“So, just to make sure, you say Soto is now in left?”

“Right.”

“Please just say correct.”

“Correct.”

“And when I asked you who’s in right for the Mets, you said I dunno?”

“That’s what I said.”

“So they still have Soto?”

“For a long time. Unless he opts out.”

“Doesn’t Soto have a contract?”

“Every ballplayer has a contract.”

“Doesn’t the contract say Soto will be a Met for the length of the contract?”

“Correct. It’s a very lengthy contract. Fifteen years.”

“That is a long time.”

“Correct. But he can opt out after the fifth year if certain adjustments aren’t made to his satisfaction.”

“Then it’s not a fifteen-year contract.”

“It is. It just might last not last longer than five years.”

“But he’s a Met right now?”

“Correct.”

“And he was the Mets’ right fielder last year.”

“Correct.”

“So why isn’t Soto still in right?”

“So they can put somebody else out there.”

“And who would that be?”

“I dunno.”

“Which you say is not a peculiar name for a ballplayer, even on the Mets.”

“It’s still a peculiar name, but it’s not the name of the Mets’ right fielder.”

“So who is the Mets’ right fielder?”

“I dunno.”

“When will the identity of the Mets’ right fielder become clear?”

“Later.”

“How much later?”

“Later this Spring.”

“That’s a long way away.”

“Not really. Spring has already started.”

“No it hasn’t. There’s like two feet of snow on the ground.”

“Not where the Mets play.”

“But the Mets play in New York.”

“The Mets don’t play in New York in the Spring.”

“Which this isn’t.”

“But it is. The Mets have already played several ballgames this Spring.”

“Did they win them?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It doesn’t matter? How could it not matter whether the Mets win or lose if we’re fans of the New York Mets?”

“Because it’s Spring.”

“It’s not spring — it’s February!”

“Spring starts in February in baseball.”

“You’re telling me that in the dead of winter, when there’s snow covering everything in New York, including the Mets’ home ballpark, that it’s actually spring, and that the Mets are playing baseball, which is something that as Mets fans we really care about, yet it doesn’t matter if they win or lose?”

“Correct.”

“What happens when it’s actually spring?”

“It’s Spring right now in baseball.”

“I mean when it’s spring everywhere.”

“When it’s spring everywhere, the Mets will be in New York.”

“When will that be?”

“Soon.”

“How soon?”

“Late March.”

“It’s still cold in late March.”

“It’s baseball season in late March.”

“But I thought baseball was the summer game.”

“It says here that baseball starts in New York in late March.”

“Where does it say that?”

“Here. On the official schedule.”

“Can you hand me the official schedule the Mets print?”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“They don’t print it anymore.”

“So what are you looking at?”

“My phone.”

“They don’t have a schedule that fits in your pocket?”

“They put it on phones. They figure there’s one in everybody’s pocket.”

“I see. So I have to look on my phone if I want to see when the Mets play?”

“Correct.”

“OK, I’m looking on my phone, and I see that like you said the Mets play in New York in late March.”

“Correct.”

“And that on the first day they play in their home ballpark, they’ll be giving out schedules.”

“Correct.”

“But you said they don’t print them anymore.”

“They don’t. Except on magnets.”

“So I can just pick up a magnet that has the schedule on it?”

“Only if you go to the game on the first day. Everybody gets one.”

“What if I can’t go to the game on the first day? What if I go on the second day?”

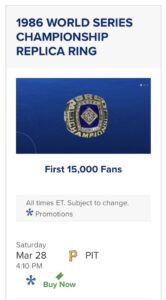

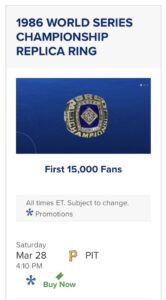

“On the second day they’re giving out replica 1986 world championship rings.”

“That sounds great! Maybe I’ll go to that game.”

“If you want a ring, you have to be one of the first 15,000 fans.”

“One of the first 15,000 fans to what?”

“One of the first 15,000 fans to go to that game.”

“How many people might go to that game?”

“Maybe 40,000.”

“Aren’t all 40,000 going at the same time?”

“They’re all going to the same game, but they each enter the ballpark at different times.”

“And only 15,000 get replica 1986 world championship rings?”

“Only the first 15,000.”

“So if I’m holding a ticket, how would I know if I’m gonna be one of the first 15,000?”

“You won’t be holding a ticket.”

“What if buy a ticket?”

“You can buy a ticket, but you can’t hold a ticket.”

“Don’t the Mets sell tickets to their ballgames?”

“They do. Look on your phone.”

“I see. Whoa, get a load of those prices.”

“Oh, they’ll take your money in exchange for a ticket. But the ticket goes on your phone.”

“So my phone has to be one of the first 15,000 phones inside the Mets’ ballpark?”

“Only if it has a ticket on it.”

“Yet there are no guarantees I’ll get a ring?”

Start bundling and lining up now. “Your best bet to get one is to line up early outside the Mets’ ballpark.”

“That will assure me a replica 1986 world championship ring?”

“Only if 15,000 people didn’t line up before you.”

“So I have to line up really early?”

“Correct.”

“Outside?”

“Correct.”

“In late March in New York?”

“Correct.”

“Where there’ll likely still be some of this snow on the ground?”

“Correct.”

“To go to a thing that I already paid for?”

“Correct.”

“To get a thing I might not get if 15,000 other people decided they wanted to line up even earlier?”

“Correct.”

“And if I don’t get the ring, I get what?”

“You get to see the game.”

“Because I have a ticket.”

“Not technically. But it’s on your phone.”

“OK, let’s say I’ve bought a ticket after looking at the schedule on my phone, and the ticket is on my phone, and I’ve decided to stand outside in late March in New York really early to get my replica 1986 world championship ring, which will be given to only the first 15,000 people…by the way, why don’t they hand one to everybody?”

“Because it says on the schedule they don’t.”

“Can you hand me the schedule where it says that?”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s on your phone.”

“Right….”

“He won’t be playing. He’s not around anymore.”

“Don’t confuse me about that again. I just want to know that if I go on the second day the Mets are home, I might not get a ring, but I will see a ballgame.”

“If it doesn’t snow. It’s going to be in late March.”

“But if it doesn’t snow, the Mets will play a ballgame.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be on first?”

“Polanco.”

“Who’s not a first baseman.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be on third?”

“Bichette.”

“Who’s not a third baseman.”

“Correct.”

“And who will be in left?”

“Soto.”

“Who wasn’t a left fielder last year, but he has been.”

“And will be for a long time probably.”

“Probably?”

“If he doesn’t opt out. And even if he doesn’t opt out, after a while, he might become the designated hitter.”

“Where on the field will I see the designated hitter?”

“Nowhere.”

“So it’s not a real position?”

“Not really, but it is in the ballgame.”

“Who’s the Mets’ designated hitter?”

“I dunno.”

“I thought you said I dunno is in right.”

“By late March we’ll know who’s in right.”

“Who will it be?”

“Maybe Benge.”

“Maybe Benge?”

“Maybe Benge.”

“You’re suggesting I watching a whole bunch of ballgames at once like I would watch a whole bunch of episodes of a TV show I really like to find out who’s in right for the New York Mets?”

“You asked me who’s in right, so I’m telling you, maybe Benge.”

“Do they have doubleheaders for that so I can get multiple games watched at once?”

“Probably not.”

“Well, can you hand me the Mets schedule so I can check?”

“They don’t print schedules.”

“Except on a magnet.”

“Except on a magnet.”

“Which they give to everybody at the first ballgame in New York in late March.”

“Correct.”

“But they don’t print anywhere else.”

“Correct.”

“And they give out other things at other games.”

“Correct.”

“But only to the first 15,000.”

“Sometimes to the first 18,000.”

“To games that might draw more than 40,000.”

“Correct.”

“All to watch a team with somebody who’s not a first baseman on first, somebody who’s not a third baseman on third, last year’s right fielder in left, and in right…”

“Maybe Benge.”

“Benge? At the prices they charge, maybe I can go every now and then, but I’ll probably wait until the weather warms up.”

by Greg Prince on 16 February 2026 4:24 pm Faith and Fear in Flushing celebrates its 21st birthday today, making this the blog that’s legally old enough to drink. And what better way to toast such a milestone than with a lyrical tribute that would seem at home in any saloon situated within the 11368 ZIP Code?

Based strongly on the genius Stephen Sondheim committed to the 1971 musical Follies, and inspired by the voice of survival herself, Elaine Stritch — you mean every Mets blog isn’t? — we’re here to tell you on this February 16 that, as has been the case since 2005…

WE’RE STILL HERE

Faith times and Fear times

We’ve seen ’em all

And, readers dear

We’re still here

Postseason sometimes

Sometimes a drop toward the rear

But we’re here

We’ve whittled magic numbers

Short of zero

Stranded men on third

When short a hero

Seen our stadium disappear

But we’re here

Felt the sting of

Spinal stenosis

But we’re here

L’s put in the books of

Howie Rose’s

But we’re here

We’ve told each other ‘LFGM’

Put too much trust into each GM

Reach contention or just pretend?

Regardless, we would cheer

Team sold to a big financier

And we’re here

We’ve been through Pedro’s, Johan’s, and R.A.’s flair

And we’re here

Harvey Day, Grandpa Bert, and Noah’s hair

And we’re here

We got through departure of deGOAT

Verlander and Scherzer both boarding a boat

Blew taps on our trumpets

As Diaz flew a jet made by Lear

We lived through Luis Castillo

And we’re here

We’ve gotten through Fred and Jeff Wilpon

Gee, that was fun and a half

When you’ve been through Fred and Jeff Wilpon

Anything else is a laugh

We’ve been through Reyes

We’ve been through Cespedes

And we’re here

Flores and Nimmo

Asdrubal Cabrera

And we’re here

Built our hopes up for Dom Smith and Duda

Applauded along when Conforto was Scooter

Held our breath tightly

When they checked Musgrove’s ear

Still, someone said, “Buck’s sincere”

So we’re here

Murph slugged us to a pennant

His ‘D’ then showed ill effect

But we’re here

Black jerseys Friday

Next day City Connect

But we’re here

First we’d lead the league through all those laps

Then came September

And we’d collapse

We blog night after night, season by season

We can’t say for why or for what is the reason

But we’re here

We’ve gotten through

‘Hey, those Mets had quite a run

Thanks a lot for adding some fun’

Or better yet,

‘Sorry the Mets weren’t much fun,

We’ll look you up when they go on a run’

Faith times and Fear times

We’ve seen ’em all

And, readers dear

We’re still here

An Endy catch sometimes

Sometimes au revoir to a Bear

But we’re here

We’ve run the gamut, Aardsma to Zuber

Grab us a 7, cancel the Uber

We got through all of last year

And we’re here

Lord knows, at least we’ve been there

And we’re here!

Twenty-one years!!

We’re still here!!!

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2026 2:47 pm In the 1978 film Heaven Can Wait, veteran L.A. Rams quarterback Joe Pendleton, played by Warren Beatty, is in the prime of his life — “at my age, in any other business, I’d be young” — when he rides his way into an apparently fatal bicycle accident. An escort from above assigned to monitor such activity (Buck Henry) dutifully swoops up Joe to move him along on his celestial journey. Except the QB knew in his bones the accident wasn’t as fatal as it appeared, and therefore heaven really could wait. His assuredness led to this exchange between Joe and the escort’s supervisor Mr. Jordan (James Mason), the elegant gentleman charged with overseeing cloudbound operations.

JOE PENDLETON: I’m not supposed to be here.

MR. JORDAN: But you are here.

JOE PENDLETON: Well, you guys made a mistake.

Even as our collective attention shifts to hamate bones and positional switches reporting to Port St. Lucie in the company of pitchers, catchers, and everybody else, I’ve found myself thinking about that cinematic exchange from 48 years ago, overcome by the idea that someone winds up where he is not supposed to have been sent. I was directed in my mind to those lines and that thought in the aftermath of learning two one-time Mets had died just ahead of the beginning of Spring Training. “One-time” sounds right here. The first man was a Met for precisely a single season. The second of them was one of us for barely more than a month.

The passing that really brought it home was the second, that of Terrance Gore. Terrance Gore was a Met in 2022. He was 34 years old. Four Mets reporting to this very Spring Training are older. No, he’s not supposed to be here. In my heart, no baseball players are supposed to enter this sort of discussion. Because baseball players wind up as human beings regardless of the profession we grew up exalting, they inevitably wind up here, as any person will eventually.

But, if there’s justice, not a person who was 34. Not a Met from 2022 in 2026. Not someone I stood up to applaud on the final night of what is now a mere four seasons ago when he connected for his only base hit as a Met. Terrance Gore wasn’t a Met so he could bat. Buck Showalter brought him in to be his primary pinch-runner ahead of the playoffs. I trusted Showalter to know personnel the way Rocky Balboa trusted Mickey to train him for his longshot bout versus Apollo Creed. Late in Rocky, Mick tells Rock, “I want you to meet our cutman here, Al Silvani.” No further discussion needed, Al Silvani is the cutman. Early in September of 2022, Buck told us Terrance was in for Travis Jankowski, which is to say he would be in for the likes of Daniel Vogelbach and Tomás Nido should such lumbering Mets reach base.

Jankowski had done a fine job as Showalter’s pinch-runner of record before the Mets squeezed him off the 40-man, but Gore was a bona fide baseball celebrity to baseball fans who paid attention to baseball minutiae. Gore, listed as an outfielder, was the entire industry’s pinch-runner of record. He was famous for running for somebody else and getting rewarded for it handsomely, collecting three World Series rings despite rarely batting or fielding. He understood his mission on those championship rosters — the Braves’ in 2021, the Dodgers’ in 2020, the Royals’ in 2015 (when he had the decency to not enter a single World Series game) — was to be speedy in spots that could alter outcomes.

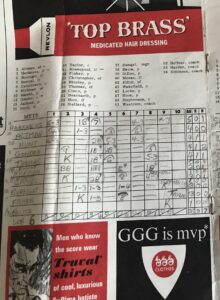

That was Terrance Gore’s role as a Met. He made it into five late-season games as a Met pinch-runner, plus a few others as a defensive replacement. In the bottom of the eight on a Sunday afternoon, as the Mets attempted to sweep away the pesky Pirates, Terrance put on what could be rightly called a pinch-running clinic.

He comes in to run for Nido.

He steals second.

He takes third as the catcher’s throw sails into center.

He comes home on Brandon Nimmo’s short single to left-center.

The Mets retake the lead.

The Mets win the game.

The essence of successful pinch-running in one quick 270-foot trip.

For Game 162 of 2022, Showalter granted Gore an entire nine innings to demonstrate his utility for the impending playoffs. As the starting center fielder, he lined a single into left off Erick Fedde of the Nationals. As baseball fans, we relish jumping to our feet and clapping when a player successfully completes what isn’t his standard assignment. Terrence hadn’t registered a base hit since 2019. It wasn’t his job, but now he had done it in front of us, and we did not hesitate to express our appreciation. We’d only been acquainted with Gore for a month, but we wanted to let him know we liked what he was doing.

The last thing Terrance Gore did, having made the postseason roster, was pinch-run in the second game of the National League Wild Card Series against the Padres. Darin Ruf led off the home sixth by helpfully placing his body between a pitch and the catcher’s mitt. The DH was HBP, and how he’d be PR for. Gore in for Ruf. The Mets were down one in the series and up one in the ballgame. What a perfect situation for a player of Terrance’s skills to make a difference. This was a man who had pinch-run 67 times in regular-season play since coming to the big leagues in 2014, plus eleven more in the postseason with this appearance. He was a specialist and this loomed as a special moment.

Then Nido grounded to second, instigating a 4-3 DP that not even the speediest pinch-runner could upend. Sometimes that’s how the ol’ ballgame goes. Sometimes that turns out to be the last time you see a ballplayer playing ball. Gore, penciled in as designated hitter, would be pinch-hit for when his slot in the order next came around. Buck didn’t have a situation for him in deciding Game Three, the one that eliminated them, and that was the end of Terrance Gore’s Mets career and, as it turned out, baseball career. The Mets wanted to outright Gore to Triple-A. He had the right to refuse and elected free agency. Nobody signed him, and that was that as far as we knew.

Not even three-and-a-half years later, you read Gore has died at 34, reportedly from surgical complications, and you can’t quite fathom it. You never can with ballplayers who were playing for your team just the other year, which might as well be just the other day. Gore is the fifth late Met whose tenure with the club took place entirely in this century, the only one whose breadth of major league experience postdates Shea Stadium. Shea Stadium lingers in the distant enough past that we’re now down to one potentially active MLBer, the as yet unsigned Max Scherzer, who can say he played there. If we mark time by stadia, anything we hear about Terrence Gore lands as relatively current, never mind indisputably recent. The 2022 Mets? I know we just let some of those guys go, but a few are still Mets on the precipice of 2026; Francisco Lindor, Mark Vientos, and Francisco Alvarez were in the starting lineup alongside Gore on October 5, 2022. Citi Field? It’s where we’ll be focusing our attention at the end of March. This March. I was just there in September for Closing Day, just as I was just there in October of 2022 for Terrance Gore’s lone Met hit.

If we imagine our lives as following some kind of path, à la Heaven Can Wait, we could do worse for a roadmap than a baseball diamond. Home to first. First to second. Second to third. Third to home. It may not work that way in life, but it’s kept baseball humming in fine fettle. Terrence Gore didn’t even have to go home to home around the diamond most games. He’d usually start at first base. He was in as a pinch-runner to pick up for the guy who found his way there from home plate. Baseball allows this, somebody fast helping out somebody who’s not. That was what Terrance Gore did so well that teams contending for a title sought him out and showed their faith in him to do it some more.

The bulk of Terrance Gore’s baseball career was about getting from only first to home as fast as possible. By that measurement, somebody owes this man an extra ninety feet.

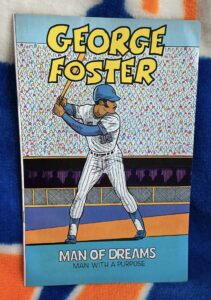

Before the loss of Gore and one other Met this February, there were a half-dozen far older Mets who died between the end of the 2025 season and the turn of the calendar to 2026: infielders Sandy Alomar, Sr. (81), Larry Burright (88), and Bart Shirley (85); outfielder George Altman (92); first baseman Tim Harkness (87); and starting pitcher Randy Jones (75). I’m also compelled to mention reliever Bill Hepler (79), who died in August without us taking a moment to note his passing. Those were seven Mets from what is unquestionably a long time ago. Six of them were Mets in the 1960s, a decade that hasn’t been active for more than fifty-six years. Alomar and Jones are the only ones I personally remember as major leaguers, and my instinct is to say I’ve been watching baseball almost forever.

Yet it was too soon for all of them to go, because baseball players became baseball players before the primes of their lives even began, and the people who cared most about them were kids whose lives had barely begun. We, those kids, get older and if we think of baseball players from our youth, we don’t see men who’ve aged into their so-called golden years. We see the athletes. We see the Mets. We see ourselves, from the inside out, viewing them as Topps intended. We don’t know it at that age, but those are their own kind of golden years, and a baseball player’s name is license to revisit them any time it occurs to us.

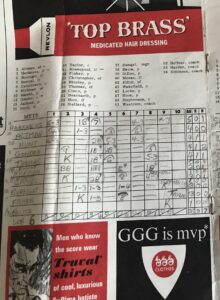

If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game! If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game!

Baseball players being human beings in their spare time precludes actual immortality. But isn’t it fun to remember the eternal excitement they evoked when we weren’t particularly judgmental, especially when they wore the uniform of our favorite team? In that respect, Pavlov’s Intro for us of a certain age was surely the highlight montage that ushered onto Channel 9’s air Mets games during the heart of the 1970s, when Shea continued to stand tall. At first sight and sound of that montage, the young Mets fan heart would race and the young Mets fan mouth would salivate. The Mets skyline logo spun into place. The instrumental version of “Meet the Mets” blared. Mets players were in action, and I mean action, with one film clip succeeding another in rapid fire procession.

A Met swinging. A Met throwing. A Met leaping. Finally, a Met sliding into home and scoring to the greatest of musical scores, all in glorious grainy color (or black & white, depending on the TV set available to you). Edits were made to delete or incorporate this Met or that as roster revisions necessitated, but every last Met shown was clearly intrinsic to Team Highlight…except, maybe, for one Met who made the montage one year without ever truly fitting within its pulsating confines.

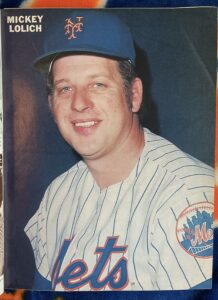

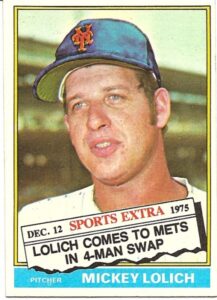

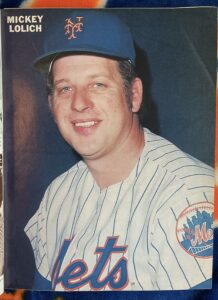

Before Warner Wolf made doing so fashionable, Mickey Lolich went to the videotape. Mickey’s snippet, spliced into the 1976 introduction, was not on film like everybody else’s. He had never been properly filmed as a Met, thus WOR was compelled to insert a frame or two from the telecast of his first start in April, lest the station stand accused of not keeping current. I wouldn’t say it portrayed the lefty import in action. Lolich, the only new Met on the Shea Stadium scene when that season commenced, stood on the mound for an instant. Maybe he went into his windup. I don’t remember if he threw a pitch. In the mind’s eye, he was just kind of there until we could return to the Mets who looked like they belonged on the Mets.

How’s that for a Met-aphor, vis-à-vis “I’m not supposed to be here”?

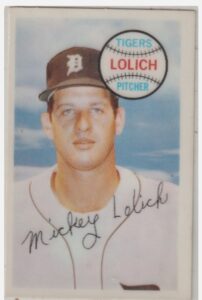

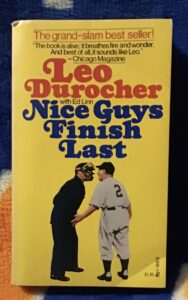

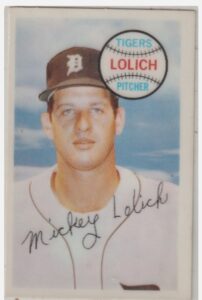

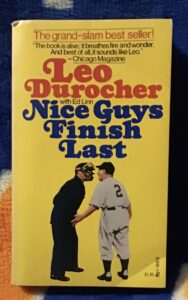

Mickey Lolich was the first Met to die this February, a couple of days before Terrance Gore. Lolich was 85, that age when you’re not bowled over by such a bulletin, even if it regards a ballplayer you remember well from when you were 13. With news of his passing, the lefty was acknowledged far and wide in baseball circles as one of the great Detroit Tigers. I heard about his death, and I’ll confess to remembering him near and narrowly as a New York Met from central miscasting — a dependable source of on-field personnel for us through the years. Listen, we’ve had loads of players who just passed through, plenty of others who didn’t live up to their established reputations upon becoming Mets, quite a few who were on the irreversible downside when they donned our duds (former Cy Young winner Randy Jones, for example). The inclination is to tick off a dozen disappointments who have spanned the decades, as if to show each other our rooting scars and congratulate ourselves on our perseverance.

Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich. Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich.

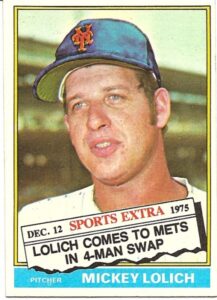

On December 12, 1975, the Mets traded Rusty Staub and minor leaguer Bill Laxton to the Tigers for Mickey Lolich and minor leaguer Billy Baldwin. There, I thought, went so much that was fun about 1975, while simultaneously inferring that 1976’s version of the Mets was diminished before it began. No 12-year-old had ever been as wrapped up in an also-ran as I was in the 1975 Mets, and about half my goodwill had just been tossed aside. Rusty Staub, besides being Rusty Staub to us ever since we traded for him in 1972, had just reached one of those heretofore unreachable statistical stars. Our fixture in right field became the first Met to crash the 100 RBI barrier in ’75. It took fourteen seasons for any Met to drive in triple digits. It took fewer than three months for Mets management to decide such a skill set was disposable. Surprise, surprise, M. Donald Grant didn’t want to keep around a beloved veteran star at the top of his game, one whose strong personality apparently clashed with his idea of how a player should act (which is to say thankful to the opportunity to call Mr. Grant his employer). Had Rusty made it through five years as a Met, he could veto a trade. Player empowerment gave Grant the worst kind of rash. It therefore became GM Joe McDonald’s job to ship Staub somewhere else ASAP and get something of value in return.

Mickey Lolich was a name. In the American League, his name had been synonymous with 2,679 strikeouts, the most recorded by any lefthanded pitcher in baseball history as of the Bicentennial; three complete-game victories in the 1968 World Series, culminating in his besting Bob Gibson on two days’ rest to take Game Seven (not to mention a home run he hit off Nelson Briles in Game Two); and a pair of 20-win seasons a few years later. Had Vida Blue not been so spellbinding over the first four months of 1971, Lolich could have claimed he was a victim of Cy Young robbery. As was, Mickey, as runner-up, won more games than anybody in the majors in ’71 (25), started more games than anybody in either league (45), struck out the most batters in baseball (308), and posted an innings total 42 frames beyond that of any counterpart (376). He followed all that with a 22-14 mark in 1972, pitching the Tigers to the AL East title and doing his damnedest to get them back to the Fall Classic. In an ALCS recalled today mainly for Bert Campaneris flinging a bat at Lerrin LaGrow in Game Two, Lolich pitched into the eleventh inning of Game One, only to take a hard-luck loss, and was no-decisioned despite going nine innings and giving up a lone run in Game Four.

Jesus, that guy was good. And you would have loved to have that guy from 1968 or 1971 or 1972 on the Mets. What a highlight player he would have been. As 1976 approached, those peaks were fading fast in time’s rearview mirror. Lolich’s last two years as a Tiger saw him lose 39 games, albeit for a team that was altogether past its late-’60s/early-’70s prime. Numbers unavailable to the baseball-consuming public in 1975, particularly his Baseball-Reference WAR of 4.0, indicate he was done no favors by pitching for the 102-loss Tigers. On the other hand, his having turned 35 was a matter of public record. All those innings on all that Lolich (bulky would be a kind description) had to have taken a toll after so many years.

At his age, in any other business, he’d be young. In 1976, in baseball, he was getting on.

Yet the Mets tried to treat him as a get. Convinced of the durability of their Kingman-Unser-Vail outfield, GM Joe McDonald figured a lack of offense, even sans Staub, wasn’t an issue that was going to bedevil the Mets. What the team fronted by Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, and Jerry Koosman needed to do, according to McDonald, was trade its most reliable stick for another arm. “One of the reasons we didn’t win last year,” McDonald rationalized upon announcing the trade, “is because we didn’t have a solid No. 4 starter. Now we go into a town for a three-game series, and the other team knows they are going to face one of the four in every game.” Too much pitching is rarely any team’s problem, but whither the offense? Whither the 105 RBIs that just went out the door? Whither the foot Mike Vail broke playing basketball during the offseason? Joe McDonald plans, the entity Mr. Jordan works for laughs.

Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal. Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal.

His introduction to the Mets nonetheless represented a shock to his Detroit-defined system, and it was made no smoother by a Spring Training that was delayed past St. Patrick’s Day thanks to an owners’ lockout. Among an informal gathering of stretching and tossing Mets, Cardinals, and Pirates in St. Petersburg, the southpaw admitted nobody in this league was familiar to him, not even on his own team. Of longtime catcher Jerry Grote, who was as much a fixture to the Mets’ staff as Bill Freehan had been to the Tigers’, Lolich told Newsday’s Bill Nack, “If he walked up to me now, I wouldn’t know who he is.”

Yet here came Mr. Lolich, wearing a boxy Mets jersey, starting the third game of the new season. Seaver won on Opening Day. Matlack threw a 1-0 shutout the second day. Lolich couldn’t maintain the momentum, lasting only two innings. He’d made two errors and had given up three Expo runs on one of those trademark windy April Shea afternoons. His spot in the batting order came up in the bottom of the second with the bases loaded and two out. Rather than let Lolich take his first swings since pre-DH 1972, new manager Joe Frazier sent up John Stearns to pinch-hit. Stearns flied out. With the Mets leaving fourteen runners on bases, Frazier and Lolich were both on their way to their first National League losses.

Things would get intermittently less horrific. It took four starts for Mickey Lolich to earn an NL win, but he did it in style on April 26, going the distance and striking out nine Braves, while working harmoniously with Ron Hodges, who, like Grote, he’d eventually met. His wins legitimately impressed. A complete game at San Francisco in mid-June. A shutout over St. Louis as June ended. Another whitewashing when Atlanta returned to town right after the All-Star break. On August 8 in Pittsburgh, as Hurricane Belle bore down on New York, Mickey withstood storm clouds of his own. He gave up eight Pirate hits, walked one Buc, struck out nobody, yet remained on the mound all nine innings in posting a 7-4 victory. It was the third and last time a Met pitcher ever won a complete game with zero strikeouts, and it was done by a pitcher who, entering that season, had struck out more batters than any pitcher in baseball history besides Walter Johnson and Bob Gibson. “Sometimes,” the lefty explained in April, “I’ll change my style of pitching two or three times a game.” Clearly, the veteran could put his versatility to optimal use.

Lolich was the personification of that little girl with the curl cliché Ralph Kiner loved invoking. When he was good, he was very good. Sometimes he’d be more than pretty good but his batters weren’t up to snuff. Lolich threw eighteen quality starts — at least six innings pitched, no more than three earned runs allowed — yet the Mets lost nine of them. Come summer, Bob Murphy was regularly using the word “snakebit” to describe Lolich’s season. Sometimes the bad-luck serpents couldn’t be blamed, as the pitcher who turned 36 on September 12 simply wasn’t able to keep pace with Seaver, Matlack, or soon-to-be Cy Young runner-up (to Randy Jones) Koosman. A fourth starter, no matter how accomplished, tends to perform like a fourth starter. Lolich’s 3.22 ERA wasn’t the sparkling stuff usually posted by Met aces of the day, but it probably deserved better than an 8-13 won-lost record on a third-place club that went 86-76. His ERA+, a metric conceived decades later to provide context for how a pitcher performs among all of his peers, was 101, or ever so slightly above average.

As a 13-year-old Mets fan in 1976, recently Bar Mitzvahed and everything, I’d like to think I had reached the age of reason. I could reason that though Lolich couldn’t keep his earned run average below three and couldn’t compile more wins than losses, that he was not bad. I kept telling myself that. He’s not Seaver, and he’s no longer the guy who gave Vida Blue a run for his money, but he’s OK. He can’t help it if they don’t score for him. And he can’t help it if we never should have traded Rusty Staub. Yeah, I still missed Rusty Staub. Did any Mets fan not? The group of Tigers Rusty went to weren’t dramatically better than the set Lolich left, but they sure seemed to be a lot more fun than the 1976 Mets. The main reason was Mark “The Bird” Fidrych talking to the ball before throwing it past batters en route to a literally sensational 19-9 year, but don’t overlook the joie de vivre provided by Detroit’s new right fielder and sometimes designated hitter. Staub played 161 games for the Tigers, drove in 96 runs, and was elected to the AL All-Star team by discerning fans everywhere. If Rusty missed us like we missed Rusty — both in the affection and run-production sense — it didn’t show in his stats.

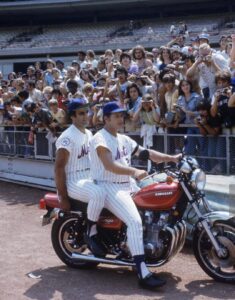

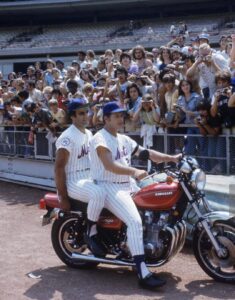

Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base side warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing. Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base side warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing.

With a year remaining on his contract, Mickey Lolich let the Mets know whatever they were planning for 1977, they could do it without him. The native Oregonian never stopped missing Michigan. It was home to him and his family. New York was a yearlong business trip. Lolich elaborated on his exit strategy for the Daily News in December of ’76:

“The season was not fun. On the days I wasn’t pitching, life wasn’t fun. I was very happy with the Mets. They were some of the finest players I’ve ever been with, and I got along well with the front office. I was disappointed in my record because I pitched better than that. So did Tom Seaver. People ask, what was wrong? Nothing was wrong. But the Mets definitely need a power hitter to help Dave Kingman.

“And the first two months were difficult with the people ridiculing me and belittling me. I got letters and heard them telling me they wanted Staub there instead of me. Sure, it reflects on me. I’ve been playing in the big leagues for 14 years. Now I want to be home.”

With that, Mickey Lolich was retired. Then, after his Mets contract officially expired, he unretired, filed for that newfangled free agency, and gave pitching one more shot, this time out of the bullpen as a reliever for the San Diego Padres, farther from Michigan than New York was. He toed the Shea mound once in his two Padre years, on August 17, 1978, throwing three shutout innings and notching his first (and only) National League save in support of Gaylord Perry’s 260th career win. Per Don Williams in the Star-Ledger, Mets fans booed Lolich when he entered he game, booed again when he batted, and cheered when he struck out. “Sure I expected it,” the ex-Met said of his reception. “That’s New York.”

At the end of 1979, Lolich decided he was done being a big leaguer for real. Back to Michigan he went for good, occasionally receiving the “where are they now?” treatment as the pitcher who went from putting up zeroes to turning out doughnuts at Lolich’s Donuts & Pastry Shop in Lake Orion, Mich. Hockey great Stan Mikita owned a place like that in Wayne’s World, but his establishment was fictional. Lolich’s new line of work was genuine. The Times visited him when the Tigers made the World Series in 1984, stressing how earning 217 major league wins had been Lolich’s then, while baking “400-dozen doughnuts a day” accounted for his now. Tensions were dissipating between him and the team he was remembered succeeding for, and, as the years went by, the idea Tigers ever traded him away must have seemed as absurd in those parts as it is in our neck of the woods that the Mets felt the need to rid themselves of Rusty Staub.

For the rest of his life, doughnuts or no doughnuts, Mickey Lolich was introduced; referred to; and thought of first, foremost, and practically exclusively as MVP of the 1968 World Series, one of the all-time great Detroit Tigers. However he spent his 1976 was just some fine-print detail. Lolich would make his final appearance at Comerica Park in 2023 as part of a pregame 55th-anniversary celebration of the championship his left arm made possible. He and a handful of his ’68 teammates stuck around to take in a promising performance from emerging Tiger ace Tarik Skubal. Skubal struck out nine, a fairly Lolichian total, but the kid on the verge of back-to-back Cy Youngs went only five innings. They were scoreless, but there weren’t that many of them. Afterward, the young lefty berated himself for not lasting seven — not nine, but seven. When Tarik tossed his first complete game in 2025, it left him 194 shy of Mickey’s career total.

Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!” Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!”

Yes, it’s how we felt about Rusty Staub, and were bound to feel the opposite of when we encountered anybody who got in the way of our devotion to and adoration of Le Grand Orange. Nothing personal, Mickey. That’s New York, too.

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2026 1:48 pm A Mets fan walks into an Applebee’s. That’s not a setup to a quip. It actually happens once a year that I know of, with me as the Mets fan. Applebee’s menu tends to shake out a bit on the salty side for my tastes, but salty is something I’ll never be if somebody is kind enough to take or, more accurately, send me there on the house every January.

My wife’s birthday, you see, was last week, and when my wife’s birthday is nigh, my sister and her husband never fail to send us a generous gift card for Applebee’s, a national chain restaurant conveniently located to where we live. Its proximity is its primary appeal to us. Barely having to drive and not having to pay equals eating good in the neighborhood. More partial to bringing in than dining out, we don’t usually take advantage of the hospitality on-premise, but this January we made an exception. We went to our town’s Applebee’s for lunch last Wednesday. It was the same afternoon the Mets introduced Bo Bichette to the press; the day after the Mets acquired Luis Robert, Jr.; a few hours before the Mets traded for Freddy Peralta. This is how a Mets fan who walks into an Applebee’s has come to mark time this January.

And who should greet Stephanie and me practically inside the door at Applebee’s but Pete Alonso? Specifically, a substantial color photo of the Polar Bear that graced the bulk of a wall adjacent to the hostess station. With each index finger raised in the direction of the crowd, Pete appeared to be celebrating one of his franchise-record 264 home runs. The image must have gone up since last January, the last time I was in there to pick up our gift card’s worth, because had it been up the year before, I would have noticed it. And had this visit been before December of 2025, I would have kvelled without qualification that a name-brand casual dining establishment — or any establishment, really — was devoting a place of prominence to the longtime signature star of the Mets.

Well, this is awkward. Now, in January of 2026, Big Pete was just another piece of flare that a joint like Applebee’s mandates to imply one of its outlets is suitably sporty and righteously regional. They also have lots of pictures of area Little League and high school athletes up as well. I didn’t check to see who among them has since graduated. I do know Alonso works in Baltimore these days.

Pete will always be a Met icon. A decade from now, that picture, if corporate hasn’t mandated its removal, will stand as a pleasant reminder of a player who did great things for the nearby team and was well-loved while doing it. A sizable portrait of Pete Alonso by then will hit like a sizable portrait of, say, Cleon Jones now. If Cleon was the de facto face of our Applebee’s, you think I’d ask to speak to the manager and request we not be shown somebody who finished his career on the South Side of Chicago, nowhere near our local Applebee’s? Yet stepping right up to greet Pete was not what I was planning on doing last week. I was having a hard enough time getting to know who’s actually on the Mets at the moment.

I wasn’t planning on this, either, but I now root for a team that features Bo Bichette, Luis Robert, Jr., Freddy Peralta, and, if his minor league deal amounts to anything, Craig Kimbrel. Fine. Great. Maybe wonderful. But I wasn’t planning on it. I’ve certainly known their names and something about their games. I didn’t know they were Mets. They weren’t until very recently. Nevertheless, here they come into my life and your life, along with some other fairly familiar ballplayers who played elsewhere in years past. To some extent, that’s every winter on the verge of Spring. Some winters it feels organic. Some winters it feels transformative in a welcome way. This winter it feels almost random. If Leonard Nimoy were still hosting his syndicated program, he’d be in search of context for these Mets.

The Mets as we knew them — the Mets with whom we lost patience on the road from 45-24 to 38-55 — ceased to exist in the segment of the offseason that bridged 2025 and 2026. Then there were a few weeks when there didn’t seem to be much to the Mets at all. A lot of deletion. Sporadic addition. Tempting as it was to lose patience with the lack of progression, that was OK. It was late December and early January. There was no baseball yet. Somebody would be playing as Mets by the end of March.

The Mets as we know them at present, at least the Mets to whom we are being introduced these days? I don’t know. I really don’t. I guess that’s OK, too. Even it isn’t, it’s going to be.

It’s a Citi of strangers, Stephen Sondheim might suggest. They’ve all come to work, come to play. Bo Bichette, a late recast for Kyle Tucker (and owner of our most soap operatic name since Blade Tidwell), evinced believable enthusiasm for becoming a Met as he chatted with the media ahead of us going to Applebee’s. He accepted a large sum in order to express his enthusiasm. He worked in a couple of opt-outs in case being a Met isn’t as awesome as he thought it could be. Shortly after his signing was reported, I got around to watching an MLB Network special dissecting Game Seven from last year’s World Series. I saw through newly opened eyes Bichette belt a three-run homer to put Toronto up early. “Hey,” I thought, “we just got the guy who did that!” Bo wasn’t playing third base for the Blue Jays then or ever; he will be for us. What’s a new season without a sense of defensive adventure?

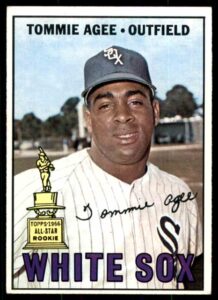

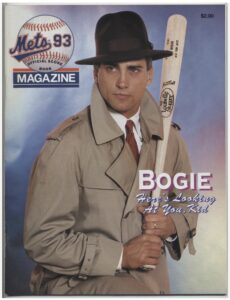

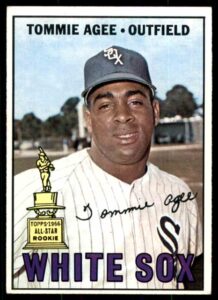

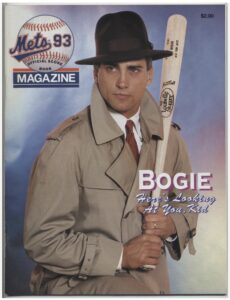

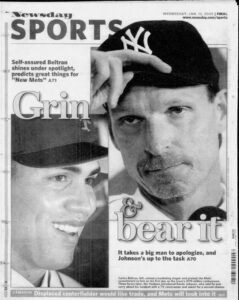

Luis Robert, Jr., is considered a heckuva center fielder and can count a fabulous season in his not too distant past. I’ll try to forget that also described Cedric Mullins last summer. Robert doesn’t necessarily have to follow directly in the footsteps of White Sox-turned-Mets stars like Tommie Agee and Lance Johnson to succeed in center. By dint of not being a Metsian Mullin, he pencils in as an automatic upgrade. Yet I am genuinely sorry we gave up Luisangel Acuña to nab him from the pale hose, though I’m sure some of that is my pinch-running obsession talking. In 2025, Luisangel Acuña pinch-ran more than any Met but three ever had in a single season? He was inserted 23 times for PR purposes, tying him with Hot Rod Kanehl (1963), Leon “Motor” Brown (1976), and Tim “Bogie” Bogar (1996) for frequency, and he did it without a widely disseminated nickname. Six stolen bases as a pinch-runner, eleven runs scored. Promising enough as an everyday player that during the one month when he received regular reps, mostly at second, he was named April’s National League Rookie of the Month.

Center fielders who used to be White Sox have been known to become Mets stars. The promise more than the pinch-running record was what made dismissing Acuña sting. When we traded for Luisangel at the 2023 deadline, it was deemed a coup of sorts. He showed up a little ahead of schedule in September 2024 and made himself extremely useful in spurts. Then he got a little lost in a middle infield logjam, and the front office guy who replaced the front office guy who acquired him saw him as no less expendable than Joe McIlvaine judged Tim Bogar. Acuña appeared on our depth chart in the same ad hoc makeover that brought us Drew Gilbert, and Gilbert’s been gone for months, becoming the next center fielder for somebody else instead of us. Yet when the world was slightly younger, Gilbert the outfielder and Acuña the infielder were joining our top draft pick from 2022, Jett Williams, who it was said could play infield and outfield, in making our minor leagues formidable. I saw Williams up close in the Citi Field press conference room when the Mets were presenting their organizational awards at the end of 2023. My private pet name for him immediately emerged: Diamond Stud, inspired by the sparkling earring he modeled. That was a blah season, but soon, I could tell myself, we’d have the Diamond Stud carving out a spot on our diamond, maybe in the same lineup with Acuña and Gilbert.

Here’s looking at kids who pinch-ran a lot. They’re all elsewhere now, with two of them never having ascended to the Mets. In my adolescence, I liked leafing to the back of the Official Yearbook to get a gander at our Future Stars, even if they tended to be Butch Benton and Luis Rosado. Anticipation is a baseball fan’s core competency. I had no idea how any of the crop lately blossoming down on the farm were going to actually fit into our big league plans, but I liked knowing they were on their way up. Gilbert went to San Francisco to obtain Tyler Rogers, one of the myriad relievers who couldn’t stem 2025’s tide of futility. Williams went to Milwaukee alongside Brandon Sproat for Freddy Peralta. I’ll no doubt applaud the first strike Peralta throws as the Mets’ 2026 titular ace, probably when he appears on NBC come Opening Day, just as I’ll put my hands together for the first fly ball Robert reels in behind him.

Fare thee well, potential Diamond Stud. Regardless of how well our veteran newcomers mesh with the likes of Lindor and Soto, I’m going to miss the budding future I was anticipating. Williams was a bejeweled anecdote to me. I hoped there’d be more to him. Sproat was already a little something. Four starts of varying return last September, but it was a beginning. I nestled Sproat between Nolan McLean and Jonah Tong to form my ideal youthful pitching core for 2026 and beyond — I dubbed them Generation MST3K as I looked forward to them coming of age and me nurturing their narrative. I was taking on the Gen-K ghost of Izzy, Pulse, and Paul from thirty years before. No, that crew never really set sail, but I had time on my side this time. Or so I dared assume. Oh well, M and T are still here. I suppose Christian Scott can be subbed in as the “S,” but it won’t be quite what I envisioned.

I’m all for improving the present product with relatively proven commodities. As of March 26, I plan to open my arms to Bichette, Robert, Peralta, Marcus Semien, Luis Polanco, Devin Williams, Luke Weaver, Luis Garcia, Tobias Myers, Grae Kessinger, whoever. I get an extra kick out of Kimbrel being here if only because he’s been around so long that I can remember it being a big deal that David Wright whacked a late-inning dinger off him in Atlanta. I know these new guys without really knowing these new guys. No matter their experience, they’re new as Mets. I’ll get to know them. At the moment they’re mostly whoever. Alonso & Co. were us. Some of Pete’s peers are still on hand. Some of the kids from the proverbial back of the yearbook remain; a few have crept toward the middle and front sections since they were freshmen. Not everybody slated to inhabit Citi soon is a stranger.

Nonetheless, this Met winter has left me feeling a chill on the cusp of Spring. Then again, so did winter twenty years ago. Carlos Delgado was precisely the kind of slugger we prized perennially. Paul Lo Duca figured as the best possible Mike Piazza successor. Billy Wagner was exactly what we needed to caulk all those Looperesque leaks. At Shea in 2006, however, they loomed as strangers, as did the spare parts we seemed intent on amassing post-2005. Endy Chavez? Jose Valentin? Xavier Nady? Duaner Sanchez? Jorge Julio? Darren Oliver? Chad Bradford from Moneyball? Julio Franco from the 1982 Phillies? Some had reputations. Some you’d have labeled lesser-known. They were all bound at some point for Port St. Lucie, itself diluted by something called the World Baseball Classic. On paper, which was something I was in the twilight of buying daily, it looked all right. In my soul, the surroundings were disturbingly unfamiliar. I felt almost isolated from my team. Seriously, who were these guys and how did they get to call themselves Mets?

Then the season started, and most of the aforementioned made great impressions, and the new Mets coalesced with the core Mets from 2005, and the 2006 Mets morphed into a division champion I cherish to this day. Four eventual Hall of Famers played for those Mets, none more brilliantly than the most recently anointed of them, Carlos Beltran, elected to Cooperstown somewhere amid Bichette, Robert, and Peralta alighting in our midst. I hope his plaque portrays him as a Met, but even if it doesn’t, Beltran wore our cap in 2006, which turned out to be quite a year for the collection of players — and fans — who did just that.

Maybe we’ll someday say something of that nature for the Mets who are currently comprised largely of accomplished whoevers. Or we’ll wonder what the hell went wrong the way we have in the wake of strangers looking better in theory than they did on the field. Either way, they’ll have our attention; then our familiarity; then some combination of our esteem and disdain. You know, like Mets every year.

by Jason Fry on 16 January 2026 11:37 am It was a confounding, frustrating season even before we learned it would be a fracture in the Mets’ timeline, with stalwarts we’d grown used to shipped off or allowed to depart and their replacements still yet to take shape. One day it will all seem like a logical story; for now it’s just baffling. But onward we go, in good times and bad as well as times we’re not sure about yet, so it’s time to take stock of the season’s matriculated Mets.

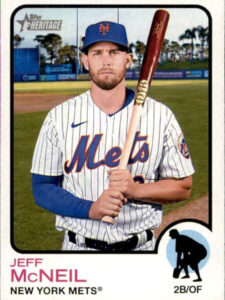

(Background: I have three binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Francisco Alvarez is Class of ’22, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who didn’t play for the Mets, manage the Mets, or get stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.)

Welcome to the study rug, fellas! (If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Off we go into the wild blue and orange yonder….

Juan Soto: It all seemed a little underwhelming somehow. Some of that was gigantic expectations — 15 years, $765 million tends to drown out everything else — and some of that was the season’s curdling into murkiness and then disaster. Soto wound up with 43 homers and 105 RBIs, which is pretty far from a down season, so maybe it’s us. Or maybe it’s that by now we’re braced for impact when it comes to the first season for a high-profile acquisition — ask Carlos Beltran or Francisco Lindor about that. (Hey, their later years turned out pretty well!) Soto’s Met career got off to what in hindsight should have felt like a foreboding note: On Opening Day he came up against Josh Hader with two out in the ninth, runners on first and third, the Mets down a pair of runs and a storybook ending set to be written … and struck out. On the other hand, Soto turned into a base-stealing machine, swiping 38 bags after never stealing more than 12. If you’d like more foreboding, though, that came under the tutelage of Antoan Richardson, who was allowed to go work for the Braves as one of the Mets’ offseason subtractions. Soto gets a 2025 Topps card, which is its own oddity: He’s Photoshopped into an old-style Mets away uniform, which he never wore because the team ditched that classic design for something that looks like it was made in a basement on Canal Street. Good Christ, I have to write how many more of these?

Clay Holmes: Hey, it wasn’t his fault. The hulking former Yankee reliever pitched pretty well as a Mets starter, aside from fatigue that had to be expected given a difficult shift in responsibilities. He saved his best moment for last, coming up big in a Game 161 wipeout of the Marlins. Unfortunately, there was a game the next day too, one that Holmes could only watch. 2025 Topps card.

Hayden Senger: Not all MLB success stories are glittering ones, nor need to be. Senger was drafted in 2018’s 24th round, which no longer exists, and hadn’t exactly got rich as a pro ballplayer: He spent last offseason getting up at 5 am to stock shelves at Whole Foods. He entered 2025 as a glove-first minor-league catcher, the kind of CV that often lacks that final call to the Show, as MLB teams have a maddening habit of finding backup catchers on other MLB rosters instead of in their own ranks. But Francisco Alvarez’s broken hamate bone opened the door for Senger to make the Opening Day roster. His debut came in that fateful ninth inning that ended with a K for Soto; shortly before that Senger was sent to the plate against Hader with the bases loaded and nobody out, looked overmatched, and struck out. He didn’t do much at the plate the rest of the year either, but try and tell him the year wasn’t a success. Topps Heritage card using the ’76 design. 1976 was the first year I collected cards, so the Michigan blue and yellow chosen for the Mets back then look right to me even though I know they aren’t.

A.J. Minter: A burly, bearded ex-Brave, Minter was brought in to give the Mets a reliable lefty arm in the pen and pitched pretty well in April. But in his 13th appearance, he delivered a ball in Washington and came off the mound with an arm shake and a grimace. He’d torn his lat, ending his season and starting a sad parade of injuries to bullpen lefties. Safe to say that wasn’t the plan. Topps gave Minter a Heritage card in its High Numbers series, preventing me from having to admit him to The Holy Books as a Brave.

Griffin Canning: An Angels reclamation project (honestly that sounds like a redundancy these days), Canning looked like a successful Mets reinvention along the lines of Sean Manaea and Luis Severino, riding a reconfigured pitch mix to early-season success. He became an early favorite of mine, too: I loved his mechanics, which were beautifully fluid while also admirably compact. Then it all came crashing down: In late June Canning watched from the mound as Lindor fielded a grounder and by the time the ball smacked into Pete Alonso’s glove, he’d crumpled as if shot and was lying on the infield grass. It was a ruptured Achilles, and the end of his season. Topps Heritage card.

Jose Siri: Siri built a reputation in Tampa Bay as a flashy center-field wizard who struck out a ton but could also hit balls to the moon, but it all went wrong very quickly as a Met: Two weeks into the season, after indeed striking out a ton, Siri fouled a ball off his shin, an innocuous mishap that turned out to be a fractured tibia. He was rusty when he returned in September and endured a nightmare game at Citi Field: Over the course of four pitches, a ball popped in and out of Siri’s glove, ending up as a double, and a bad route turned a single into a triple. Two ABs later, Siri came to the plate with boos raining down and was promptly zapped with a pitch-clock violation. He struck out in that AB, struck out in his next one, and was then pinch-hit for Cedric Mullins, whose arrival was greeted with cheers. (Mullins then … wait for it … struck out.) Siri never had another AB as a Met; he ended up with an .063 average, two hits, and having to remember that fans actually preferred seeing Mullins trudge to the plate instead of him. Now that’s a bad year. Topps Photoshopped him into a Mets uniform for Heritage; they should have added a bag over his head.

Max Kranick: A postseason ghost in 2024, Kranick became corporeal in April and earned early plaudits as a courageous reliever with a talent for wiggling out of tough spots. Unfortunately April was a small sample size; Kranick fell back to Earth in May, got sent down, and soon needed a second Tommy John surgery. Old Topps card as a Pirate.

Justin Hagenman: Turns out his first outing was his best one. Hagenman was pressed into service against the Twins in a mid-April bullpen game and did yeoman work, at least until his statistical line was blemished by after-the-fact crumminess from Jose Butto. (You may remember this game as an early installment in one of my least-favorite 2025 serials, The Revenge Tour of Harrison Bader.) Hagenman appeared now and then later during the season, mostly in mop-up duty. Hey, it’s a living. Topps Heritage card.

Jose Azocar: Collected some hits in April as a fourth outfielder, went zero for May, and became a Brave in June. Have to confess I remember none of that. 2024 Topps card as a Padre.

Jose Urena: A lion-maned veteran reliever, Urena logged one day as a Met, pitching not particularly well during a laugher against the Nats but still earning a save because that’s what the rulebook says. He then spent May as a Blue Jay, June as a Dodger, August as a Twin and September as an Angel. Wheeee! He’s now a Rakuten Golden Eagle. Double wheeee! Old Topps Heritage card as a Padre, one of the few things he wasn’t in 2025.

Kevin Herget: Herget took the baton from Urena in the middle-reliever parade of guys you probably don’t remember either. Middle relief has always been a spaghetti at the wall business, but new rules about options have made managing the last bullpen slots truly ruthless, with teams content to bring a guy up, put him on waivers or release him, then reclaim him after another team’s done the same. The Mets plucked Herget out of the Brewers’ farm system in the 2024 offseason, called him up for a lone appearance at the end of April, put him on waivers, watched (maybe) from afar as he made a lone appearance for the Braves, claimed him from the Braves, used him in five games over three months, made him a free agent at the end of September, then signed him again a week before Christmas. Harget went to Kean University; I own a Kean University beach towel though I have no idea how it came into my possession. Some old card as a (Springfield) Cardinal.

Brandon Waddell: A lefty journeyman who’d pitched in both Korea and China, Waddell stood out (mildly) from the relief mob by logging 11 appearances and being at least reliable-adjacent. Which means you’ll see him again in some uniform next year — possibly even ours — and for whatever subsequent years he shows up and demonstrates that he’s still left-handed. Syracuse Mets card.

Chris Devenski: I first saw him at an unseasonably warm end-of-April bullpen game and my reaction was, “Who the heck is that? When did they call this guy up?” Such are the joys of the reliever parade. Devenski’s end-of-season numbers wound up being pretty good, or at least good enough to get a contract with the Pirates for 2026. Syracuse card.

Genesis Cabrera: Best known for throwing a pitch that hit J.D. Davis in the ankle during a feisty Mets-Cardinals game back in 2022, the prelude to Yoan Lopez drilling Nolan Arenado and a lot of pushing and shoving that saw Alonso tangle with Cabrera and the immortally monikered Stubby Clapp. Honestly that was more memorable than anything Cabrera did in six up-and-down appearances for the Mets in May as they looked for a lefty to replace Danny Young, who’d replaced Minter. Cabrera then collected 2025 paychecks from the Cubs, Pirates and Twins, AKA the Full Urena. Let’s use Cabrera’s Mets tenure as an opportunity to celebrate the inexplicably Canadian Stubby Clapp, whose father and grandfather also went by Stubby; as does his oldest son; and whose wife is named Chastity Clapp. I am not making any of that up. Syracuse card issued after Cabrera had come and gone.

Blade Tidwell: Once a moderately heralded Mets pitching prospect, Tidwell made his debut in May against the Cardinals and it was a pretty typical maiden voyage: some pitches made and some not made on the way to an ugly bottom line that wasn’t as bad as the numbers, provided you squinted a little. Subsequent outings required more squinting and the Mets shipped Tidwell to the Giants at the trade deadline along with Butto and Drew Gilbert. Tidwell’s still young and finding his way, but that felt like the opposite of an endorsement. 2025 Topps card.

Austin Warren: There are 1,450+ innings in a big-league season and it takes a lot of arms to get through them. This bit of wisdom appears in every THB chronicle, because it’s true. Nothing personal, Austin. Syracuse card.

Jose Castillo: A husky lefty reliever, Castillo’s road to the Mets was a bit odd: He imploded against them in late May while pitching for the Diamondbacks and was wearing blue and orange a little more than a week later. Since the beginning of September he’s been employed by the Mariners, the Orioles, the Mets again and is now a free agent. I suppose this is why middle relievers rent instead of buying. A card as an El Paso Chihuahua, which I feel bad about but was the best I could do.

Jared Young: Once-upon-a-time Cubs prospect came over to the Mets after stop-offs in Memphis and Korea and didn’t leave much of an impression. One of a growing number of ballplayers who sneak into Topps sets with autograph-only cards, yet another sign of civilization’s rot. Syracuse card.

Justin Garza: Five June appearances, none of which I remember. A 2025 minor-league card as a … I have no idea what team this is, actually. At least he’s not a Chihuahua.

Tyler Zuber: Pitched two not very good innings for the Mets in June, became a Marlin, and returned to Citi Field at the end of August to face his old team during Jonah Tong’s debut. I was in the stands and registered Zuber’s arrival but had completely forgotten his approximately 20 minutes of Mets service time. Zuber then gave up seven earned runs in a single inning, which I suppose is one way to be memorable. If you’re curious, yes, he displaced Don Zimmer and is currently the 1,287th and last man on the all-time Mets A-Z roster. Syracuse card.

Frankie Montas: Montas looked solid against the Mets as a Brewer in the 2024 wild card series, possibly leading to his signing a two-year deal with New York. It didn’t exactly work out, as Montas was felled by a torn lat in spring training and then pitched abysmally while rehabbing at Triple-A. With no real alternatives, the Mets summoned him to start against the Braves in late June. That went well, but his next start was a shellacking in Pittsburgh (I was lucky enough to see it in person) and he then alternated pedestrian outings with getting lit up, followed by exile to the bullpen. His year ended with the revelation that he needed Tommy John surgery; he was DFA’ed and will get paid $17 million to be hurt next year. 2025 Topps card.

Richard Lovelady: Mets fandom had a titter over the veteran lefty going by “Dicky,” though I wonder if Richard “Stubby” Clapp wanted a word. (Stubby Clapp, unexpected star of the THB Class of 2025!) Exactly what the newest Met wanted to be called led to a spirited discussion on SNY, with Gary Cohen’s eyebrow audibly arched (no really, you could hear it) and someone in the truck presumably told to be aggressive about cutting Keith Hernandez’s mic. Whatever those on a first-name basis called him, Lovelady spent the summer appearing and disappearing from the roster, with not particularly impressive numbers. The Mets must have liked something they saw, though, as they made him their first offseason free-agent signing. Old Topps Heritage card as a Royal.

Jonathan Pintaro: A flaxen-haired reliever who’d opened eyes in indy ball, Pintaro was cuffed around by the Braves in his lone MLB appearance, with Edwin Diaz forced to ride to the rescue at the tail end of a not particularly close game. This is an inherent unfairness of The Holy Books: Pintaro could spend a decade as a reliable contributor and still be stuck with this sour cup of coffee as his entry. Here’s hoping he makes this more than a theoretical injustice. 2025 card as a Binghamton Met.

Colin Poche: I was in the park for Poche’s lone appearance, the middle game of the series in which the Mets stepped on about 50,000 rakes while getting swept by the Pirates. Poche relieved Huascar Brazoban and turned a narrow Pittsburgh lead into an impossibly wide gulf. That sucked, but it isn’t what annoys me most about Poche. That would be his pain-in-the-ass baseball cards. He has a 2020 Chrome autograph card and a 2023 Tampa Bay team-set card, both nonstandard; I wound up needing two copies of the former and haven’t been able to secure the latter. Fortunately this hasn’t cost a lot, since Colin Poche cards aren’t a particularly hot commodity, but I’ve now conservatively spent 10 times the duration of his ineffective Mets tenure trying and failing to secure his annoying baseball cards.

Zach Pop: Another one-gamer, Pop’s second pitch as a Met became a home run onto the Soda Plateau for fucking Austin Wells, who looks like a guy who pesters other Little League dads about buying an above-ground swimming pool. In all, Pop’s Mets career consisted of nine Yankees faced, five of whom hit safely. Not a way to endear yourself to much of anybody, least of all me. Old Topps card as a Marlin.