The year is 1970. Or it should be. That was the plan as we approached the third installment of our OF-3B/3B-OF series. We spent one segment focused mainly on 1962, because you can’t begin to understand the Mets’ signature position shuttle without delving into the start of something absurd; and we spent the next segment traipsing across the rest of the Sixties, even extending a toe over the decade line to recognize the fallout from miscasting young outfielders as third basemen. Once we saw what became of ex-Met Jim Hickman and ex-Met Amos Otis (All-Star berths as outfielders), it felt safe to move ahead in time.

Yet we can’t leave the 1960s just yet, because the Mets OF-3B/3B-OF paradigm isn’t whole without a detour into a variation on the form, as if the form of continuing playing players out of position required varying. Within the OF-3B/3B-OF universe we’ve explored once, twice, now about to be thrice, there is a hardy strain of versatility it wouldn’t occur to a person exists: the C-3B-OF. The Mets have used a dozen of them.

Mind you, unlike the conversion of third basemen to the outfield or outfielders to third base, most of the alternative deployment of catchers by the Mets has been anecdotal, maybe accidental. Not everybody who has caught for the Mets has been a catcher by trade. For all their attempts to twist outfielders into third basemen and third basemen into outfielders, pretzeling someone who played a lot of both and a little of the other and directing him to crouch behind the plate hasn’t been something the Mets specifically planned on much, save for conceptually foreseeable contingencies.

One night in Los Angeles, however, several seasons before the Sixties were done, the Mets went there — albeit for an unforeseeable contingency. Hence, for a little while longer, the year is not yet 1970.

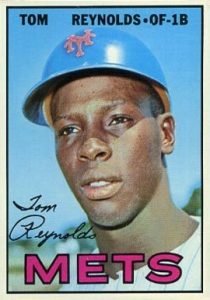

Curiosity, unintended as it was, got the best of the Mets on July 27, 1967, when they had to turn to Tommie Reynolds to catch. Most every opponent got the best of the Mets in those days, so why not curiosity?

Tommie Reynolds, not considered a catcher as late as July 26, 1967, became the epitome of a Mets emergency catcher the very next night because, although the Mets were carrying three catchers on their 25-man roster, none was available to catch from the eighth inning forward at Dodger Stadium. To borrow a phrase from what was then the future, that’s so Mets. By 1967, five years had passed since the 1962 Mets went into the history books as the one, the only, the Original Mets who landed at 40-120 on merit, verve and panache. The Polo Grounds hadn’t stood since April of 1964. It had been just over two years since Casey Stengel presided definitively over the double-edged Amazin’ nature of the Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York. And rookie Tom Seaver, the leading edge of the narrative-altering professionalism that would soon take hold in Flushing, was already a 10-game winner in the major leagues. Yet, even with so much of what defined the Mets as the ditziest franchise ever known receding into their rearview mirror, the Mets were still very much capable on any given evening of being so Mets.

July 27, 1967, was one of those evenings.

“The New York Mets have lost 603 games in their turbulent six-year career,” Joe Durso wrote in the Times after the 7-6 loss of July 27, “but No. 603 may live longest in Met annals and Wes Westrum’s memory.”

Goossen left the game. Sullivan was out of the game. Grote was the new catcher. Grote was the Mets’ catcher most of the time. Like third base, catcher had been a difficult position for the Mets to fill since ’62, but 24-year-old Grote represented a Seaverean harbinger regarding the talent and determination that would eventually transform expectations at Shea. The Mets outright stole him from the Astros in advance of the 1966 season, sending pitcher Tom Parsons to Houston on the heels of a 1-10 campaign (which encompassed one more win than Parsons ever notched as an Astro). Grote didn’t yet hit much, but he began to harness his defensive gifts in New York and provide the Mets with the stability they’d lacked behind the plate from about the minute the Mets drafted Hobie Landrith with their very first expansion pick. Landrith’s Met legacy was twofold: Hobie was the catcher to whom Stengel alluded in his remark about the necessity to have a catcher in place lest the team find itself facilitating passed balls; and Hobie wound up designated as the “player to be named later” once the Mets had to compensate the Orioles for the acquisition of M.E.T. himself, Marvin Eugene Throneberry (whereas Throneberry was almost immediately named Marvelous Marv).

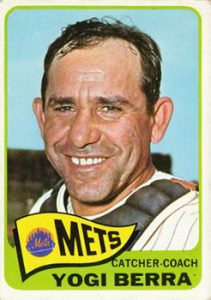

Hobie Landrith, Choo Choo Coleman and Chris Cannizzaro headlined the cast of a dozen-plus receivers Stengel and Westrum employed between 1962 and 1965. Some were better than others at preventing passed balls. None truly excelled at multiple aspects of the game. Well, Yogi Berra did, but that had been in his past life, the one that stretched from 1946 to 1963 in the Bronx, the one he thought he was through with once he removed his mask and chest protector; turned his cap around; and signed on to manage the Yankees in 1964. He won a pennant, yet got fired anyway, finding refuge in Flushing soon after. Berra came to the Mets to aid the former skipper who held him in the highest of esteem. “My assistant manager,” Casey labeled Yogi when Yogi was in the process of winning three MVPs, almost too many World Series rings to count and “a place in Stengel’s affections that no other ballplayer ever quite matched,” per Durso’s 1967 biography Casey: The Life and Legend of Charles Dillon Stengel. “I never play a game without my man in the lineup,” Stengel said of Berra when Berra caught.

Now Berra — whose playing career included 262 games in the outfield and one at third base (on Closing Day of the 1954 season, which was also the last time the Philadelphia Athletics ever took the field; you could look it up) — was set to coach. Mostly coach. Maybe catch. As if the public relations benefit of grabbing recently dismissed and eternally lovable Yogi Berra from the coldhearted Yankees wasn’t enough to further boost the Mets’ image — grabbing recently dismissed and eternally lovable Casey Stengel from the coldhearted Yankees is what put the Mets on the PR map in the first place — they brought into their fold another Cooperstown-bound character ahead of the 1965 season, all-time winningest lefty Warren Spahn. The imagination ran wild at the thought of the heretofore helpless Mets trotting out an immortal battery in their fourth season, never mind that Spahn at 43 and Berra at 39 weren’t exactly jibing with the Youth of America movement Stengel liked to herald.

Spahn was going to pitch and coach, in that order. Yogi came to the Mets to coach and maybe…maybe…catch. “Put him out there,” the thinking went in St. Petersburg, per Phil Pepe’s accounting in 1974’s The Wit and Wisdom of Yogi Berra. “He couldn’t hurt the Mets.” And, indeed, “Yogi gave it everything he had. He trimmed down, got in shape, and went through a tortuous spring training.” The season opened with Spahn in the rotation and Berra assisting Stengel as hitting instructor and first base coach. That was April. In May, with none among the Mets’ catching corps in what you’d call a hitting groove, Yogi was coaxed to strap on his gear again. He caught a pair of games shortly before his 40th birthday. One was a 2-1 routegoing victory for Al Jackson in which Berra recorded 12 putouts (11 on Ks, one on a play at the plate). He even singled twice. But it was less a comeback than a hill of beans, and by the time to blow out those forty candles rolled around on May 12, 1965, Yogi was once more a full-time coach. When it came to catching for the Mets, Berra wasn’t built for the long haul.

Grote was developing into a different story. He had talent. He had a temper, too. You might love his skills, but lovability wasn’t about to show up on his scouting report. “Orneriness,” is what Art Shamsky labeled as the catcher’s defining character trait in After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the ’69 Mets, the 2019 book he wrote with Erik Sherman. “Grote was a bitch,” Cleon Jones affirmed in the same volume, at least when it came to preparing for and playing the game. But if the players were getting together with their wives and kids? The Grote who took part in those affairs was a totally different Grote in the left fielder’s eyes. “The nicest guy you’d ever want to meet,” according to Cleon. “He was gentle.” Jerry Koosman, who regularly shared rides to work with Grote (not to mention a notable World Series-winning embrace), agreed: “He’d be as nice as could be until the ballpark came into sight. Then he really changed personalities. He’d get the red ass.” Or as one reporter of the era pegged the catcher, per Shamsky and Sherman, “Will Rogers never met Jerry Grote.”

But Bob Hendley, one of his 1967 veteran batterymates, reflected decades after the fact for author Bill Ryczek that despite his youth and less than lengthy fuse, Jerry came across as “an experienced, take-charge guy” and appreciated that “he had some fire about him”. By 1968, Grote would be an All-Star. By 1969, he’d be a world champion. Before he left Shea in 1977, he’d catch 1,176 games for the Mets, 350 more than anybody else ever has. In 1992, Seaver would stand before a sun-drenched throng in Cooperstown and group Grote with Johnny Bench and Carlton Fisk as the trio of catchers integral to the success that led to the occasion of Tom’s Hall of Fame induction. And, somewhere along the way, Jerry Grote — “about whom we could never figure out what or who he liked” as Shamsky described him some 50 years later — would tame the fire about him enough to make it manageable.

July 27, 1967, however, was not that evening.

When you’ve drawn the ears and eyes of three men in a four-man umpiring crew, you’re stacking the odds against your staying in the game. Sure enough, Jackowski dismissed Jerry summarily. The Mets started the night with three catchers. They were down to none, with the game not quite finished. Those aren’t good odds, either.

Westrum, a scoop of vanilla to Stengel’s bottomless tutti-frutti sundae, at least had colorful instincts. “I thought of me or Yogi” to catch. Wes, a two-time All-Star in his New York Giant playing days, hadn’t caught since 1957, his first base coach Berra not since that 1965 cameo. Yogi, being Yogi, asked Sudol if he could catch the eighth and ninth despite not appearing on the Mets’ active roster.

“No chance,” Sudol answered Berra, according to Durso. “It takes 24 hours for you to get reactivated by the commissioner. If you do that, though, you can catch all nine innings.” Sudol was the umpire behind home plate when the Mets played 23 innings in the second game of a doubleheader in 1964 and would go on to officiate similarly extensive Met affairs in ’68 and ’74, so perhaps Ed had an inkling that more than a couple of frames lay ahead.

Sure enough, the Mets rallied in the eighth, scoring three times to take a 5-3 lead. Whether they were in a righteous mood to wreak revenge because Jackowski left them without a legitimate catcher or they simply took advantage of a lukewarm Perranoski is not certain. What became clear as the top of the eighth unfolded was who would be taking Grote’s place. It would be Reynolds, who batted in Jerry’s spot (he was intentionally walked). Reynolds was neither in the starting lineup nor begin the inning on the Mets’ bench. He was in the bullpen, warming up pitchers.

But don’t take that as an occupational obligation. Tommie, 25, was an outfielder by trade but, being a good team man, would help out now and then by crouching down as needed and offering his glove as a handy target. “I warm up pitchers sometimes,” he clarified, “but I never caught behind the bat before.” Other eligible Mets had, if not lately. Tommy Davis as a junior in high school. Ed Kranepool as a senior in high school. Ron Swoboda’s experience was limited to limited to catching a round of BP in Puerto Rican winter ball once, but that didn’t stop him from snapping on a shinguard. They all stirred from the bench and volunteered to go behind the plate. Westrum, however, opted to call out for help.

“The phone rang in the bullpen,” Reynolds said. “They said Grote was out of the game. They called me in.”

Actually, it wasn’t that simple, at least from the Mets’ viewpoint. Bob Bailey was batting in the bottom of the eleventh with runners on first and third and one out. Bailey, by Reynolds’s reckoning, foul-tipped a ball off of Tommie’s mitt and out of play. The umpire saw it differently. So, not surprisingly, did the batter.

Jackowski: “The batter swung right over the ball.”

Bailey: “It never hit my bat.”

Reynolds” “It hit the bat, then it hit the glove.”

Reynolds must have been pretty sure, given that when the ball trickled away, he made no move to chase it down. It’s worth noting Bailey didn’t motion for the runner at third, Nate Oliver, to start running, indicating perhaps that he knew it did hit his bat. Jackowski, though, would only tell the new catcher, “I didn’t say it was a foul tip.” Suddenly Reynolds was in pursuit of the ball and Oliver was on his way home.

Jack Fisher, usually a starting pitcher, took the loss after following five of his fellow Met hurlers to the mound (Reynolds caught three different pitchers in all). Jerry Grote wound up fined a hundred bucks for leaving Westrum high and dry. Plus he was “sternly” lectured via long-distance call by club president Bing Devine. “I have nothing to say,” was Grote’s postgame reaction. “Nothing at all.” Bill Jackowski’s night finished with the Mets screaming at him and reporters questioning him. “Lay off me, fellas,” he pleaded to the press. “It’s been a tough four hours.”

And Tommie Reynolds? For four innings of major league catching experience, he received his stripes — “I can’t think of anything tougher to try in baseball”; he received a pain somewhere south of his rear end — “my legs are killing me”; and, for our purposes, he received membership in a secret society within a a slightly less secret society within a society that’s never been much of a secret inside Met circles. When Tommie Reynolds — often spelled Tommy in the papers, portrayed (amid apparently murky circumstances) by Topps as Tom — entered the game of July 27, 1967, to catch, he became only the second Met ever to have played outfield and third base and catcher.

On Opening Day, Reynolds, a Rule 5 selectee from the Kansas City A’s during the preceding offseason, pinch-ran for Tommy Davis and took his spot in left field. Before April was over, Westrum gave him a whirl at third, moving Tommie in from right to give Ken Boyer a few innings off. At that point, Reynolds had become the 31st third baseman in Mets history and the franchise’s eleventh OF-3B/3B-OF. In early May, Westrum started him at third to provide a 1-for-31 Boyer a breather. Tommie caught a pair of popups and “got a hit,” Larry Fox reported in the News, “which could prolong his tour at third another day” (it didn’t). When Grote inadvertently paved the way for his unplanned cameo behind the pate, Reynolds was thrust into becoming the second Met you could call an OF-3B-C.

Yes, there was one who preceded him, and yes there’d be more than a few after him…including one fellow whose occasionally testy company we’ve already shared quite a bit of in this essay. We’ll get back to him down the road a piece. Before we do, though, let’s meet the OF-3B-C/3B-OF-C who started it all.

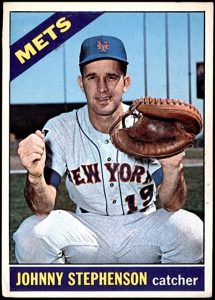

“Casey said, ‘Johnny go up there and get a base hit for us,’” is how Mets reliever Bill Wakefield remembered it for Ryczek. “John kind of looked at me and rolled his eyes, as if to say, ‘I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do in this situation.’” No wonder. Stephenson, in his first major league season, was batting .074 as a bench player. The opposing pitcher was Jim Bunning, the Mets’ daddy that Father’s Day, throwing merely a perfect game at Shea Stadium. Thus, if you know Johnny Stephenson for anything, it’s for making the final out of a most historic Mets defeat. If you’d like to know anything else, it’s that after playing some third base and outfield in 1964, he reverted to his natural position of catcher for the rest of his big league days, mostly putting his other positions behind him. On June 19, 1965, after his recall from Triple-A Buffalo, Stephenson went behind the plate for the first time in the majors, catching the final three innings of the Mets’ 2-1 loss to the Giants.

Stephenson, who played until 1973 and would go on to manage and coach in the Mets’ system from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, had always been a catcher more than he’d been anything else. Playing multiple positions became baked into his skill set once he broke a finger; not wanting to be sidelined, he inserted outfielding into his repertoire and kept working his way up the Met chain. As the lefty-swinging John aspired to make the big club in the Spring of ’64, Dick Young noted in the Daily News that the kid had the inside track on the third catcher’s slot, behind Jesse Gonder and Hawk Taylor, “because he can play center as well”. (Pre-Tommie Agee, the Mets were forever in the market for center field solutions.)

The third base segment of his Met career was born, as was much with the Mets in the early years, of desperation. In an April loss at Pittsburgh, Stengel burned through a plethora of pinch-hitters to tie the game late, compelling the manger to quickly “remake the infield,” in Young’s words, with “John Stephenson, a catcher-outfielder, given a crack at third.” The remake crumbled, in part, because “Stephenson fluffed [Manny] Mota’s tough bunt,” which set up the losing run. Young, however, cut the youngster a break, noting John had “worked out at third and looked good enough to get a try there. The bunt he tried to barehand was tough to make a play on.”

But Stephenson was first and foremost a catcher. He caught Nolan Ryan in the young fireballer’s major league debut as a Met and he caught Nolan Ryan when Ryan was fanning batters at a ferocious rate for the Angels. (Of Ryan’s major league record 5,714 strikeouts, Stephenson handled 212 of them.) Everybody who can claim time as a Mets third baseman, Mets outfielder and Mets catcher, with the glaring exception of Tommie Reynolds, would have self-identified as a catcher all of, most of, or little of his respective MLB career, even if it was only in a “you might make yourself more useful if you learned to catch” utilityman role or the “stay ready just in case” realm of emergency catcherdom. The 3B-OF/OF-3B detours during their Met stays were just that. The Mets needed somebody to fill in here and/or there. Sometimes it was a catcher. Sometimes it was at third base. Sometimes it was in the outfield.

The times when it was most prevalent postdated the Met tenures of Stephenson and Reynolds, both of whom were gone from Shea well before 1969. You might even say there was a golden age for the triad of Met versatility. Let us, then, in the next installment of OF-3B/OF-3B, visit the decade when the Mets attempted, more than at any other time in their first sixty years, to triple down on certain players’ ability or willingness to play wherever asked…when that was only part of the positional paradigm that continued to plague/propel the Mets.

We’ll dive deep into the 1970s, and a little into the 1980s.

METS WHO PLAYED THIRD, PLAYED OUTFIELD AND CAUGHT

JOHNNY STEPHENSON

Mets Debut as 3B: April 26, 1964; 14 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as LF: May 16, 1964; 11 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as C: June 19, 1965; 98 G as a Mets C

TOMMIE REYNOLDS

Mets Debut as LF: April 11, 1967; 72 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as 3B: April 29, 1967; 6 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as C: July 27, 1967; 1 G as a Mets C

JERRY GROTE

Mets Debut as C: April 15, 1966; 1,176 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as 3B: August 3, 1966; 18 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as RF: July 12, 1972; 2 G as a Mets OF

JOHN STEARNS

Mets Debut as C: April 16, 1975; 698 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as 3B: June 28, 1978; 29 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as LF: August 18, 1979; 6 G as a Mets OF

ALEX TREVIÑO

Mets Debut as C: September 11, 1978; 172 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as 3B: October 1, 1978; 43 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as LF: September 16, 1981 (Game 2); 2 G as a Mets OF

CLINT HURDLE

Mets Debut as 3B: September 12, 1983; 9 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as RF: October 2, 1983 (Game 2); 11 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as C: April 24, 1985; 17 G as a Mets C

GARY CARTER

Mets Debut as C: April 9, 1985; 566 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as RF: June 26, 1985; 6 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as 3B: July 22, 1986; 2 G as a Mets 3B

MACKEY SASSER

Mets Debut as C: April 10, 1988; 261 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as RF: April 19, 1988; 31 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as 3B: May 11, 1988; 2 G as a Mets 3B

JEFF McKNIGHT

Mets Debut as 3B: June 10, 1989; 13 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as RF: September 27, 1992; 1 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as C: April 21, 1993; 1 G as a Mets C

JIM TATUM

Mets Debut as C: April 6, 1998; 4 G as a Mets C

Mets Debut as LF: April 27, 1998; 4 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as 3B: May 16, 1998; 3 G as a Mets 3B

MIKE KINKADE

Mets Debut as 3B: September 8, 1998; 4 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as LF: April 6, 1999; 17 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as C: April 15, 1999; 1 G as a Mets C

ELI MARRERO

Mets Debut as CF: June 11, 2006; 7 G as a Mets OF

Mets Debut as 3B: July 2, 2006; 1 G as a Mets 3B

Mets Debut as C: July 8, 2006 (Game 2); 2 G as a Mets C

Those old batting helmets, eh? Unbelievable how accessorized batters are these days, and everything has a logo on it.

Greg, you really did a lot of impressive research, as you’ve done throughout the series. What a deep dive into the statistical and newspaper summaries of what occurred 50+ years ago. Such troves of information, all organized by our Faithful blogger.

(BTW, I have no recollection at all of Jim Tatum.)

I may have been the only one in the universe rooting for Johnny Stephenson to break up that perfect game. I’ll never understand why anyone says to root against your team just to make history for an opponent. Do it the old fashioned way….earn it! Anyway, my feeling is similar to what happened eight years prior to Larsen’s perfect game. If the ball was thrown behind the batter, the umpire was beginning to call strike three the moment the ball left the pitcher’s fingers. Too bad for Johnny. A perfect bunt down the third base line would have been a fitting way to stop a perfect game.