Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

But there ain’t no Coupe de Ville

Hiding at the bottom of a Cracker Jack box

—Meat Loaf

If it feels like it’s been a while since the last official Mets game, it has been. As of Sunday, it will be the longest it’s ever been. June 14, 2020, will mark 259 days since September 29, 2019, last season’s Closing Day. That tops by one the 258-day void between August 11, 1994, the last game before that year’s players’ strike, and April 26, 1995, Opening Night of the next year at Coors Field. That arid spell stretched on forever, and we’re about to surpass forever.

So for reasons beyond the sport’s control and maybe a few within its negotiating grasp, we’ve involuntarily tried a baseball-less season. It doesn’t seem preferable to anything. But is it preferable the least favorite baseball season of your life?

No.

Of course not.

Are you crazy?

But isn’t not having any baseball somehow better than being subject to terrible baseball, specifically terrible Mets baseball made worse by the subtraction of the best Met ever?

Let me think about that for a sec…

Still no. You’re still crazy. Believe me, lacking any recent games to contemplate, I’ve thought it through thoroughly.

I’ve personally experienced 51 Mets seasons, from 1969 through 2019. I recently sat down and attempted to formalize some chronic late-night noodling, daring to list, from 1 to 51, my personal favorite Met seasons; or my least- to most-favorite Met seasons from 51 to 1. (This differs from dispassionately discerning and ranking The Best Met Seasons of All-Time, which I took my shot at here.) I’ve known what’s bundled at the top for some time. The bottom cluster, though, I had to dwell on, even though you wouldn’t necessarily want to dwell in it. You go down there, you better just beware of the bad, bad season you’ll call the one you liked least.

Yet you still liked it. I mean, no, you didn’t like like it, but there was baseball. There were occasional wins. There were intermittent great plays. There were players you looked forward to seeing play. There was, if you were lucky, a player you had no idea was going to play and you grew excited once you realized he was going to play every day.

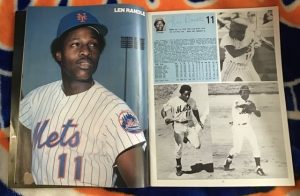

In 1977, my least favorite Mets season among the 51 I’ve truly inhabited, that player was Lenny Randle. He couldn’t save ’77, but he could make it go down incrementally smoother.

Players like Lenny Randle are why they revise editions of the yearbook — or used to. You want to examine his picture, pore over his stats, absorb his biographical nuggets. You want to root for Lenny and the Mets, sometimes in that exact order. You want to wrap yourself in the recurring surprise of the presence of someone who wasn’t there when the season began and now you can’t imagine your ballclub continuing without him. You want all the Lenny Randle you can get.

We got Randle by the bushel in 1977. It was one of the two elements of my least favorite season I remember most fondly. One was the first trip I took to Shea Stadium without adult supervision, an LIRR jaunt to see Lenny and the Mets take on (and lose to) the St. Louis Cardinals. That’s an unabashedly fond memory for a fourteen-year-old. Lenny coming aboard at the end of April and flourishing in the months ahead is the other. That’s a fond memory for a Mets fan of any age.

Otherwise, 1977 is the season the Mets fell through the floor of the National League East and traded Tom Seaver while most everybody I knew suddenly decided to switch their local baseball allegiances. No wonder it’s my least favorite season. What was wrong with it is easy enough to divine and despair. Let me evade the tag of “least” as best I can and stick to the favorite part of my least favorite season. Let me remember the revelation that was Lenny Randle of the New York Mets.

When the Mets gathered in St. Petersburg for Spring Training, Lenny Randle was not with them. He was a Texas Ranger, across the Florida peninsula in Pompano Beach. Randle had been a Ranger since before there were Texas Rangers, back to 1971 when the Rangers were the Washington Senators. In 1974, Lenny was one of the Rangers who shocked baseball, rising from the Seasons in Hell depths of the AL West to challenge the Oakland A’s for divisional supremacy. Texas fell short but behind Manager of the Year Billy Martin, MVP Jeff Burroughs, Cy Young runner-up Ferguson Jenkins and Rookie of the Year Mike Hargrove they excited a nation of baseball fans. They certainly got an eleven-year-old on Long Island stoked about their upset chances. Randle, mostly shifting between second and third base and switch-hitting .302, became one of my vaguely favorite American Leaguers from a distance.

In the Spring of ’77, I had no idea how close Randle would soon be getting to where I lived and rooted. The Rangers were maneuvering legacy prospect Bump Wills to second and Lenny to the bench. Tensions couldn’t help but be a little high between the incumbent infielder and his manager, Frank Lucchesi. Randle indicated he didn’t want to be a Ranger reserve. Lucchesi grumbled, “I’m sick and tired of these punks saying, ‘Play me or trade me.’ Let them go find another job.”

That’s what Randle did, indirectly, taking harsh exception to being called one of those things you don’t call a grown man in your employ (management training has come a long way over four decades). While the Rangers were in Orlando visiting the Twins, Lenny lost his temper and started communicating with his fists. Lucchesi took a punch under the right eye, with a fractured cheekbone to show for the altercation. It didn’t play as much of a fight in the public imagination. Randle was a 28-year-old athlete. Lucchesi’s age at the time of the incident was reported as 49 back when 49 seemed incredibly old. The manager went to the hospital. The player went on suspension, with his reputation severely bruised.

That was in late March. In late April, it was announced that somebody had made a deal to take the potential social leper off Texas’s hands: the Mets, of all teams. I say “of all teams,” because the Mets seemed like the last team in the world to take a flier on a presumed malcontent. M. Donald Grant didn’t like the players who talked back. Now the Mets were welcoming one who hit back? Somehow, the Mets managed to be sort of progressive in this instant, looking past the ugly episode and assuring themselves that Randle was still the person who, prior to Lucchesi labeling him a punk, had been “probably the most popular Ranger among his teammates,” according to Sports Illustrated.

“Every report on him from scouts and from people who knew him at Arizona State,” Mets GM Joe McDonald told the Times, “says that he is a gentleman and the incident in Florida was uncharacteristic.”

Still, it was uncharacteristic for the Mets of 1977 to take questionable-PR chances or attempt to improve their ballclub. They hadn’t make any moves in the offseason and the stagnation showed. Perhaps McDonald was inspired by a fairly recent episode of M*A*S*H in which Hawkeye and B.J. plot with a North Korean prisoner who happens to be an excellent English-speaking surgeon to create a new identity for the captured doctor, presenting him as One Of Ours so he can help heal the wounded, which is the whole idea of medicine in wartime, as the series mentioned once or twice. Not yet wise to the elaborate scheme, Col. Potter is surprised to find he’s in receipt of new, eminently qualified personnel.

“You know, Radar,” the 4077th’s commanding officer remarks to his company clerk, “this is the first time I Corps has sent us help without us screaming about it.”

That’s how I felt. It never occurred to me the Mets would go after Randle. After the first winter of free agency came and went with the Mets leaving all pursuable talent essentially unbothered, it never occurred to me the Mets would go after anybody. Yet here Lenny Randle was, in San Diego, coming in for defense in the eighth inning, replacing John Milner in left (Randle played every position but first base and pitcher during his twelve-year big league tenure). I can honestly say I’ll never forget that Saturday night of April 30, 1977.

I’d love to tell you it’s solely because Lenny Randle made his Mets debut in the 4-1 win that raised Tom Seaver’s record to 4-0, but in the interest of full disclosure that nobody asked for, it’s because I stopped up the downstairs toilet while my parents were out. We didn’t own a plunger, so I had no idea what to do except finish watching the Mets and the Padres, and work on crafting a delicate explanation for why the bathroom my parents relied on was shall we say out of order.

My explanation was not accepted any better than any of the words Lucchesi expressed regarding Randle in Florida, but we borrowed a neighbor’s plunger; bought one the next day for future emergencies; had a long discussion about how much paper to not use; and decided it would be best to confine my business to the upstairs bathroom for the rest of eternity.

Talk about fear in flushing.

Life went on. Randle went on. The first day of May found Lenny starting at second base, collecting three hits that included a triple, stealing home and sparking the Mets to completion of a three-game sweep of San Diego. Frazier was no Lucchesi when it came to managing the former Arizona State Sun Devil. “I wish I had four or five more just like him,” Cobra Joe said after a splash of exposure to his newest player.

We definitely could’ve used more Lenny Randles. The creeping malaise that was the 1977 Mets was impervious to the charms and impact of a lone burst of talent and personality, no matter how engaging. The wins against the Padres were an aberration. The Mets were headed for the basement, and their biggest stars — Seaver and Dave Kingman — were headed out of town. So was Frazier. On the last day of May, Joe was the ex-manager of the Mets. The new skipper was another Joe — Joe Torre, promoted from the active roster. The first move the player-manager made was to install Randle, who’d been mostly filling in at second while occasionally bouncing into the outfield, as his everyday third baseman and leadoff hitter. Torre had obviously kept his eyes open en route to taking Frazier’s job. Randle had batted .341 across his first month as a Met.

To thank Torre for the vote of confidence, Lenny singled, doubled, walked twice and scored twice on May 31, elevating his average to .352. The Mets were starting a hot streak (it wouldn’t last), Torre was starting a managerial career (it would take him to the Hall of Fame) and Randle was starting daily and becoming the undisputed best thing about the 1977 Mets. Once Seaver and Kingman were traded on June 15, there wasn’t much competition, but Lenny likely would’ve earned the distinction on his own.

The hitting wouldn’t swelter forever, but the average stayed above .300 for the rest of the season. The running threw caution to the swirling Shea wind, resulting in probably too many caught stealings but also a new club record of 33 bags swiped. The fielding at third was fine enough so that the 1978 Mets Yearbook wasn’t engaging in hype when, after ticking off his string of offensive accomplishments, it praised Randle for having given the Mets their “steadiest play ever at that position”.

Beyond the production, Lenny Randle was a fun guy to have around, not a small factor in the most unfun non-pandemic season imaginable. Emerging from the stormy circumstances that the revised edition of the 1977 yearbook did its best to downplay (“his much publicized run-in with Rangers’ manager Frank Lucchesi in ’77 spring training made him available to Mets”), Gentleman Len seemed genuinely happy to be here when hardly anybody else did. “It takes a certain player to be able to play in New York,” Lenny would assess in retirement for ubiquitous oral historian Peter Golenbock, and he was clearly one of them. He lit up every Kiner’s Korner he guested on in a year when Mets were sorely lacking for stars of the game. Lenny had received good advice from one of his coaches when it came to the postgame show.

“Willie Mays would tell me to go talk to Kiner,” Randle remembered for the book Down on the Korner. “He was a legend to me.”

For one season, Lenny was a legend of perhaps not quite Kiner-Mays proportions, but in 1977, especially after June 15, you learned to not expect too much. On Saturday afternoon, July 9, a day devoted to playing stickball with/against a frenemy of mine (he’d committed the traitorous sin of quitting on the Mets and taking up with that other New York team, thus revealing a disturbing paucity of character), a transistor radio kept us apprised of what the Mets and the Expos were up to at Shea. They were up to extra innings. Extra, extra innings. In the seventeenth, with Lee Mazzilli on first and two out, Randle crushed a Will McEnaney pitch to end the game in the Mets’ favor, 7-5. I don’t remember how the stickball turned out, but as far as I’m concerned, I won the day.

And that wasn’t even Randle’s most memorable Met moment of the week. That would come at Shea on Wednesday night, July 13, as Lenny batted versus the Cubs’ Ray Burris in the bottom of the sixth with the home team trailing, 2-1. That’s when things went dark. Literally.

“I thought to myself, ‘This is my last at-bat. God is coming to get me,” the third baseman said of the situation that enveloped him. Randle’s mortality wasn’t really in quite so dire a shape. It was just a blackout of all five boroughs that lasted until the next day. That’s all. The Mets-Cubs game was suspended until mid-September, when Randle completed his plate appearance by grounding to short. It took two months to play the full nine innings, but the Mets lost. Usually it took only two hours.

The Mets’ darkest season was Randle’s brightest. The next year, Lenny was the Opening Day starting third baseman, carrying expectations. Perhaps they burdened him, for Randle in his second Met year couldn’t hold a candle to Randle in his first. Lenny ended April batting .155 and never broke .250. His stolen base total plunged and he was getting thrown out almost as often as he was being called safe. Before Spring Training ’79 was over, so was Randle’s Mets career, with the shining star of ’77 (and his salary) released altogether and replaced at the hot corner by Richie Hebner. The surly erstwhile Phillie seemed determined to prove the new former Met’s theory that it takes a certain player to be able to play in New York. Hebner wasn’t that certain player, but let’s call that another story for another least favorite season.

Randle didn’t last very long at Shea, but he surely put the favorite in “least favorite,” which is a most valuable asset for any fan who would never think to shop his loyalty around the Metropolitan Area. We don’t remember that his ship sank in 1978. We remember that he made us feel as if we were riding the high seas with him every time he batted in 1977. Knowing Lenny as we did, little wonder that in 2015 an MLB Network documentary celebrated this character who once endeavored to blow a fair ball foul as “the most interesting man in baseball”. And little wonder that he became a Mets fantasy camp coaching mainstay. As FAFIF correspondent Jeff Hysen reported from Port St. Lucie in January of 2009, “Lenny Randle stressed the importance of not colliding with anybody — he said that when a fly ball was hit his way, he would yell ‘get the [frig] out of the way!’ It was very windy and tough to catch the flies. After I did, Randle chest bumped me.”

Just as a gentleman does.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

Lenny Randle was one of my favorite Mets of ALL TIME. When I played 3B in the schoolyard, I was Lenny Randle.

The ONLY Yankee I ever rooted for was not Doc, or Darryl, or ‘Coney,’ or even Kingman. It was Lenny Randle in 1979.

Then he was profiled on ’60 Minutes,’ while he was playing in the Italian Baseball League, and he sang ‘I’m A Ballplayer.’

He appeared to be the nicest guy in the world, which made that incident with Frank Lucchesi all the more shocking. And even more surprising is that the pristine prudish Mets would even pick him up after his one month suspension.

He was also one of the first guys to hit a homer just over the newly built LF fence under the auxiliary scoreboard.

Good Times!

Thanks for the memories.

Remember when as a Mariner he blew that bunt foul? Pure genius. The bright spots were few and far between in those days but Randle was one of them.

Brilliant as always Greg.

“Talk about fear in flushing.” — like the amazing punchline to a decades-long joke.

Wonderful. Lenny was truly a bright spot. Had no idea Lucchesi was only 49. I’d have bought 64. Then again I’m now older than John McNamara was in 1986.

For me, though, 77 was not worse than 78 or 79 – at least we had Seaver, and hope, for a few months….

When I think of that era of Mets baseball, I tend to think Maz, John Stearns, and Joel Youngblood (my fave, though I couldn’t tell you why in a million years). But yeah, for that one season Lenny was the sparkplug. Shame the engine was on the fritz.

Please, please, PLEASE tell me that Richie Hebner isn’t going to be the subject of your ’79 review…

It would indeed be appropriate to have Hebner, one of the worst human beings to don a Met uniform, represent one of the most downtrodden seasons in Met history. However, if we choose to look back with fondness rather than with anger, Maz or Stearns or Youngblood might better fit that bill.

All Mets for All Seasoms will be revealed in time.

Saddest conversation, ever? Ringing your neighbor’s doorbell in the middle of the night …

– Joe? What is it??

– Hi, Bob.

– Why’re you up in the middle of the night?

– So. Uhm. May I borrow your plunger?

Yikes. About as sad as the 1977 Mets!

Stuffed toilets and the year of the Seaver trade. Talk about plumbing the depths!

By the way, I despise Heb as much as the next guy. But when you consider that, among other objectionable ex-Mets, you’ve got at least one grifter, two spouse abusers, a guy who liked to throw cherry bombs out of moving vehicles, a convicted murderer, and Bobby Bonilla, Richie Hebner might not even make the Top 10 of Worst Met Humans Ever. Just saying.

Come to think of it, I’m wrong about Bobby Bo. He’s not an ex-Met, he’s a current Met.

Hey, isn’t Bobby Bonilla Day coming up? =)

I can laugh about it, because it’s not my money the Wilpons keep pissing away. :D

[…] At Least We Had Lenny Randle » […]

I know those late 70’s seasons were awful, but ’93 was unbearable in its own hellish ways.