Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Jimmy quit

Jody got married

I should’ve known

We’d never get far

—Bryan Adams

Together they started fewer than 100 games as Mets, yet there may be no trio of Met starting pitchers that occupies as definitive and oft-referenced a shared place in club history as Generation K. Considering that Generation K never exactly existed, that’s quite an accomplishment.

You know the members of the band: Jason Isringhausen, Bill Pulsipher and Paul Wilson. They are introduced in that order here because I came to know them as IPP in my earliest online Met days on AOL, in 1994, when we couldn’t get enough of abbreviating things. Izzy, Pulse and Paul were going to be as big as Tom, Jerry and Gentry, maybe bigger than Doc, Ronnie and El Sid. Really, though, when you think about it, those accomplished threesomes weren’t exactly trios the way Izzy, Pulse and Paul were. True, they also emerged in temporal proximity as young, hard-throwing Met starters at a juncture when the body Metropolitan yearned for a shot of youth, but in each case, their umbrella was the rotation itself. The Seaver Sector and the Gooden Gang didn’t need to be cordoned off as something else.

IPP was going to be something else. They were something else before they were anything. In retrospect, they were a trope. They were the Next Big Thing. Maybe every wave of a team’s pitching prospects — particularly on the Mets, where we consider freshly cultivated arms our birthright — comes off that way. The Mets were cultivating a crop of starting pitchers in the mid-’60s, pre-Seaver, before we knew we were synonymous with starting pitching, when any Big Thing the Mets developed would have been their First.

Yet IPP was different. IPP coalesced as a unit in the Mets fan imagination. They were going to arrive directly and thrive immediately. The Mets of the 1990s, wandering through a desert of irrelevance to anybody who wasn’t seeking a primitive Internet bulletin board to dissect their every tentative step toward respectability, would follow.

Yeah, it was gonna be great.

But never mind how my formerly virtual friend Jason and I met in real life for the first time for the express purpose of watching Pulsipher pitch. This is about Bill and his prospect buddy Jason — Pulse and Izzy. In 1995, Pulsipher was judged further along, so he was the first to take a turn for the big club. It didn’t go particularly well if you go by hits (9), walks (6), runs (7) and winning (didn’t). But Bill Pulsipher, 21 years old and brimming with stuff, was here. Despite missing the strike zone too much and getting lit up when he found it, Dallas Green left his neophyte lefty in that Saturday afternoon for seven long innings, which meant that at the end of the day, Pulse had seven innings of big league experience more than he’d had that morning. Our and presumably his dream was coming true.

The next phase was seeing what Jason Isringhausen could do. Pulse had been promising at Triple-A Norfolk: 6-4 with a 3.14 ERA. Izzy was incandescent: 9-1, 1.55. About the only headlines the Mets were making in July of 1995 revolved around their hesitancy to call up the 22-year-old righty who was overmatching the International League. The months after the 1994-95 strike had not been kind to the Mets, who had lost whatever momentum they’d garnered in ’94 and reverted to dreaded 1993 form. Maybe less embarrassing to the human race, but distressingly less competitive in the standings. At the All-Star break, the Mets sat nineteen games under .500 and nineteen games from first place.

BRING UP IZZY or words to that effect rang out from the back pages of the Post and the News. Flagship radio station WFAN might have taken a call or two or two-thousand echoing the sentiment. It made for more optimistic buzz than the other Met story of the summer, which was where might the Mets dump their remaining contractual obligations to Bret Saberhagen and Bobby Bonilla.

We got our Izzy wish on July 17, which is to say we got only so much of our wish, because being a Mets fan in the middle of the 1990s could never be about unalloyed wish-fulfillment. Sure, Jason Isringhausen would make his major league debut, against the Cubs at Wrigley Field, appropriate enough given that the kid was born and raised in Illinois. What was inappropriate that nobody in New York could plan on seeing what all the Izzy fuss was about because 1995 was the heyday of The Baseball Network. Granted, The Baseball Network lacked a heyday, but we who constituted the viewing public were stuck with it just before and just after the strike (baseball always could shoot itself in the foot).

In case you’ve forgotten, The Baseball Network was designed to limit the exposure baseball fans had to their favorite baseball team. One night a week, your local ABC affiliate would show one game, which meant nobody else could show any game, even in cities that included two teams, even on cable systems whose summertime programming revolved around telecasting every game the local teams played. On the Monday night of Izzy’s debut, it was decided that the one game the New York market would be treated to, on Channel 7, was the Yankees and White Sox, neither of whom were doing noticeably better by July than the Mets and Cubs, and neither of whom were featuring the first career appearance by a pitcher for whom a fan base was salivating en masse.

The one time in your life you would have welcomed hearing from Fran Healy on SportsChannel, he was nowhere to be heard.

There was radio, fortunately. WFAN actually advertised this Mets game as an event, and their frequency the only place where you could follow live the major league debut of Jason Isringhausen. Circa 1995, WFAN generally promoted Mets games as infomercials for mediocrity if they promoted Mets games at all. But this was an event. This was potentially the start of something big. This was potential incarnate. This was 9-1, 1.55 for the Tides showing his stuff for the Mets. You couldn’t look, but you had to listen.

Jason Isringhausen sounded good. Izzy pitched seven innings and gave up only two runs, keeping the Mets tied until they could pour on some offense in the ninth. Speaking of pouring, the baseball gods deluged the other New York and other Chicago team with rain at Yankee Stadium, leaving their game in an official tie and giving TBN/ABC an excuse to switch the Mets-Cubs game into New York. We couldn’t see the very beginning of Izzy, but we got a clue as to where he and we were going.

We were on our way. The Mets of Izzy and Pulse (and, by the trade deadline, no longer of Bonilla or Saberhagen) effected one of the most remarkable in-season turnarounds in their history. It might as well have aired on The Baseball Network for all of its long-term resonance, but it really happened. The 1995 Mets, who had bottomed out at 35-57 on August 5, surged to finish 69-75. It wasn’t technically a split season à la 1981, but it may as well have been. That 34-18 spurt reset perceptions and expectations. The team that had been on the road to nowhere had taken a detour. In that unforgettable late summer of 1995, we took off on a rocket ship fueled by the indefatigable grit of Jeff Kent; the five-tool elegance of Alex Ochoa; the unshakable poise of Carl Everett; the clubhouse singalongs to Hootie & the Blowfish. Ms. Pac-Man struck a blow for women’s rights and a young Joe Piscopo taught us how to laugh.

All right, so the last two are from a Simpsons flashback to the spring of 1983, but you get the idea. Everything seemed bright and beautiful for the Mets of tomorrow today. Nineteen Ninety-Five was finishing strong on more than a wing and a prayer. The two wings that belonged to Izzy and Pulse did the heaviest, hopefulest lifting. Pulsipher’s third start, in Florida on June 27, became his first win, and for a dozen starts over two months, Bill registered an ERA of exactly three. The only obstacle to his continued progress was some elbow soreness. An MRI revealed sprained ligaments. Rest was prescribed for the final few weeks.

Isringhausen, meanwhile, never stopped winging and bringing it. Like Pulse, Izzy notched his first victory in his third start, with eight innings of one-run ball over the Pirates at Shea on July 30. Unlike just about everybody in modern major league starting pitching, Izzy revealed himself a decisionmaking machine, earning either the W or L in eleven consecutive starts. Most of them were W’s. It’s as if Izzy wouldn’t have it any other way. On September 15, I saw him scatter thirteen Phillie hits over seven-and-a-third innings and somehow pull down the 4-1 win; never before and never since has a Met pitcher won a game when giving up that many hits. Jason entered the season’s final day, against the division champion Braves, on a 9-2 tear. Even though his last outing would be marked ND, it wasn’t as if Izzy hadn’t done his job. With eight more scoreless innings, our phenom’s ERA dropped to 2.81.

An impression was made. This player who hadn’t been in the majors until mid-July wound up fourth in NL Rookie of the Year balloting (Hideo Nomo won; Chipper Jones placed second). Further, Izzy made Mets rookie pitching history. Nobody who’d come up so late in a Met season — right after the midpoint of the strike-shortened 144-game campaign — had ever done so much winning right out of the box. Going 9-2 overall would be astounding from April until October. Izzy crammed all of his wins into a two-and-a-half month window. By comparison, Jacob deGrom in 2014 and Noah Syndergaard in 2015 also won nine games as callup starters, but both of them debuted in May. Rick Aguilera notched ten victories, but was called up in June 1985. Izzy was a young man in a hurry that hadn’t quite been seen before at Shea.

Oh, and at Binghamton and Norfolk, over 26 starts, Paul Wilson completed his first full season of professional baseball by going 11-6, with a 2.41 ERA, striking out nearly a batter an inning across 1995. Baseball America ranked him the sport’s No. 2 prospect heading into 1996.

If only 1996 had played out as we had scripted it in our minds. Had it, IPP would have been A-OK and the Mets would be ready to roar some more as they usurped the Braves’ position in the division for the rest of the ’90s. This was how it was supposed to work. We get the pitching, we get the glory.

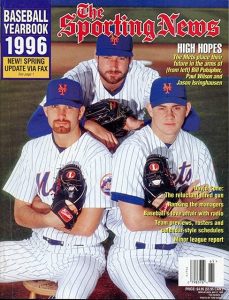

We didn’t get the pitching. Not this pitching, anyway. After they posed for the irresistible St. Lucie group photo that codified their collective status as the Next Big Thing — about the time the admittedly clever Generation K nickname took hold in the press — Izzy, Pulse and Paul peeled off to their individual fates. Pulse, first to the big leagues, was first to all but disappear from the picture. The elbow pain remained. Tommy John surgery was needed. Pulse didn’t pitch in 1996.

Izzy and Paul did, though neither of them with consistency. Wilson’s much-anticipated debut fizzled. There were a handful of tantalizing outings here and there, but Paul’s 1996 was a trial by fire, and the verdict was a 5-12 rookie season saddled with a 5.38 ERA (it was over six when September started). Izzy the sophomore struggled, too: 6-14, 4.77 ERA. The Mets stumbled backward as well, losing 91 games and erasing almost all signs of their stunning competence from 1995. By the end of ’96, the Met pitchers and the Met future was hardly a story in New York.

Except, as mentioned above, there never was a Generation K. There were some publicity photos and there was some projecting. There was definitely some pitching, just not a ton of it. Ninety-eight New York Mets games over a span of six seasons were started by Jason Isringhausen (52); and Paul Wilson (26); and Bill Pulsipher (20). That’s about ninety more than it felt like in the wake of their mostly not pitching at all.

That’s because Generation K never pitched in the same rotation. They weren’t three Mets together in the same season, unless you’re generous enough to factor in the major league disabled list. The injury-laden details are gory in the baseball sense, but in brief…

• By 1997, Paul was hurt and Pulse wasn’t back; it was all we could do to return Izzy, who’d had his own miseries, to the Met mound by late August.

• Come 1998, all we’d have as active evidence of IPP was Pulse: some bullpen work and a lone doubleheader start that did not go well. Then he got traded to Milwaukee.

• Izzy realighted as a Met in 1999 sans distinction. Then he, too, was traded to shore up a bullpen that needed a reliable arm, which Izzy was thought to no longer possess (though it’s not like Billy Taylor, for whom Izzy was sent to Oakland, had one by this point).

• Pulse came home in 2000, but the homecoming was brief, and he’d be traded once more that season, to Arizona for the second coming of Lenny Harris. All the while, since 1996, Paul had been rehabbing in hopes of resuming what theoretically could still be a substantial career. At age 27, he finally got to start a major league game, on August 4, 2000 — for the Devil Rays, one week after the Mets dispatched him and Jason Tyner to Tampa Bay for Rick White and Bubba Trammell.

Of the 98 starts Izzy, Pulse and Paul accounted for as Mets, only 14 came after 1996.

Young pitchers who don’t make it…it’s a very common tale. Young pitchers who don’t make it in combination? That’s been known to happen, too. “Ain’t no way to keep a band together,” wise pianist Del Paxton advised callow drummer Guy Patterson in That Thing You Do!, a 1996 release, as it happens. “Bands come and go. You got to keep on playin’, no matter with who.”

The trio that split apart would. Wilson’s comeback with the Devil Rays got him back in the game to stay, at least for a while. Paul won eleven games in 2004 for the Reds, earning Opening Day honors the next season versus Pedro Martinez and the Mets. He’d keep pitching until 2006. Pulsipher was in the majors as late as 2005, with the Cardinals, but Pulse really liked pitching, so he just kept going in the minors, affiliated and otherwise, until 2011. He did get to be part of a championship outfit in the New York Metropolitan Area, helping the Long Island Ducks to an Atlantic League title in 2004.

Jason Isringhausen had the longest name of the three pitchers and the longest run of success. With Oakland, Izzy became a top-notch closer, saving more than thirty games twice and making the AL All-Star team in 2000. He brought his refined relief act back to the National League in 2002 and continued to lock down games for St. Louis, saving as many as 47 in a single season. The Mets saw him plenty, for better and worse. In August of 2006, it was Izzy who gave up the game-losing home run to Carlos Beltran in the memorable 8-7 slugfest at Shea that served to tease that October’s NLCS matchup. By the postseason, Isringhausen was on the shelf again, which was too bad, considering his hip injury paved the way for the rise of Adam Wainwright en route to another dramatic Beltran at-bat.

But we weren’t done with Izzy yet. In Spring Training 2011, fifteen years after Generation K seemed so real, its most distinguished alumnus returned to St. Lucie like a swallow to Capistrano. This was no sentimental journey, however. The Mets were short of solid relief pitching (when aren’t they?) and the Mets took a chance on a 38-year-old righty who’d been out all of 2010 but maybe still had something left in the tank. Now Jason Isringhausen was the veteran, passing on his knuckle-curve wisdom to young Bobby Parnell and, once Frankie Rodriguez was traded, getting outs in ninth innings to close out Met wins. On August 15, Jason Isringhausen notched the 300th save of what had turned out to be a long and distinguished major league career. He’d pitch one more year, for the Angels, before retiring in 2012.

We had ups and downs with the kids. The ups were scintillating. The downs got Dallas Green fired. When the dust settled, the Mets were in surprisingly good shape. In 1997, with almost no IPP presence, they were legitimate Wild Card contenders. In 1999, the year Izzy was traded, they went to the playoffs for the first time since 1988, relying mightily on pitchers who pitched in 1988: Al Leiter, Rick Reed, Orel Hershiser. Bobby Jones, who rose to the majors a little before IPP came into focus and was never attached to Generation K despite being their generational peer, was the only homegrown kid starter who lasted deep into the Bobby Valentine era. (He also had his own Generation… sort of.) If you consider an Ikea dresser that leaves parts strewn all over the floor from its construction yet is somehow functional, you get an idea of how the Mets were built to win by the end of the 1990s.

They did it without Izzy. They did it without Pulse. They did it without Paul. You wouldn’t have bet in 1995 that the Mets would make it near the mountaintop by the end of the 20th century without any of IPP contributing. Maybe that’s why we shouldn’t bet on baseball.

Should we be reflexively distraught at every mention of Generation K? That’s our instinct. Their failure to stick as intended is drilled deeply into the cautionary tale compartment of our psyche. From a human standpoint, feeling sad that at least two of those pitchers didn’t live up to what was forecast for them seems the decent thing to do, though Bill Pulsipher and Paul Wilson were, in fact, professional baseball pitchers for a pretty long time, and we’re more likely to ask them for their autograph than they are to ask us for ours. And Jason Isringhausen has those 300 saves. He didn’t make the Hall of Fame, but he did make the Hall of Fame ballot.

From the Mets fan perspective, is it awful that Generation K wasn’t a sequel to Seaver, Koosman & Gentry or Gooden, Darling & Fernandez (or a prequel to the best of Harvey, deGrom & Syndergaard)? I suppose. We’ve wanted every pitcher who comes up to the bigs for us to be big for us forever. Not every pitcher can be. We were fortunate that by 1997 we overcame their collective absence and that by 1999, quite frankly, we weren’t really thinking about them.

Yet here I am, a quarter-century removed from 1995, thinking about those guys, recalling how much fun it was fun to look forward to those guys, and to revel in the first sample size one of those guys in particular gave us. I can’t help but think that brand of fleeting happiness was indeed something worth generating.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

Even more depressing than thinking about how Generation K didn’t perform as expected/hoped is thinking about might have happened had the Mets been willing to trade them as prospects. If they had traded 2 of the 3, they could’ve named their price. I know, the Mets boards on AOL would’ve gone crazy, but…

So here’s something I didn’t know about Bill Pulsipher, which actually explains a whole lot:

https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2034773

I’m reasonably certain that, on my deathbed, I will still be able to conjure up a disgusted snort of disappointment and frustration with regard to Bobby Parnell.

Bobby Parnell was horrible. I had not thought about him for a while, and I cannot wait until I forget about him again.

Parnell actually had a pretty good season as a closer, bunch of saves, hellacious stuff – then he was injured, was out for a ridiculously long time, and couldn’t recapture his stuff when he came back. That gets him more of my sympathy than my scorn. Believe me, there are plenty of attempted closers from Mets history more likely to give me nightmares. Heck, we don’t have to go back any farther than last season.

Are we sure Izzy was 22 at his debut? On that cover he looks more like 12!

With Harvey invoked here, and I know, everything’s gonna be revealed in due time, but I wonder again whether he’ll come up in the series, too. And whether it’s gonna be delirious 2013 (to a certain point…….) or more 2017, where everything has finally crashed and burned …

Based on the feedback to this entry, screw Harvey, let’s deep-dive Parnell.

How often do you and Jason say “huh, didn’t see that coming” after a post?

One never knows, do one?

[…] Land of Trope and Dreams » […]