Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

By 2001 I’d been a Mets fan for a quarter-century, which seemed long enough to have things down. But that was the year that introduced a new wrinkle. The Brooklyn Cyclones had come to town, returning pro ball to the borough for the first time since Walter O’Malley ruined everything. Now we could see minor-league games in Brooklyn as well as big-league games in Queens, and root for players who might eventually make their way to Shea.

The Cyclones were an unexpected phenomenon that inaugural season. Manhattan hipsters flocked to Coney Island, joining old-school Brooklyn leather-lungs and families from here, there and everywhere. They packed Keyspan Park, the Cyclones’ trim, sunny ballpark on the beach, tucked beneath the old Parachute Jump. Visiting players used to sleepy games with a couple of hundred spectators would look around in surprise as Cyclones fans made a hellacious racket thanks to the stadium’s metal bleachers. The stadium was great fun, offering between-innings skits that were appropriately bush league with just the right amount of irony added; musical choices a heckuva lot cooler than Shea’s; and an amusingly shambolic ringleader in Sandy the Seagull, a pudgy, sandaled mascot who seemed to have sauntered in through a side door from The Big Lebowski.

That would have been enough for a wonderful summer, but the Cyclones were also good, with a flair for the dramatic. They won their first home game, played before a host of dignitaries, after being down to their last strike in the bottom of the ninth. In the playoffs they beat their fellow newcomers, the Staten Island Yankees, and won the first game of the best-of-three New York-Penn League finals, giving themselves a chance to wrap up the championship at home. Unfortunately, that game was scheduled for Sept. 12, and was never played. The Cyclones had to settle for being co-champions — the tiniest of losses given the terrible circumstances, of course, but also not nothing.

Emily and I were in the stands several times that first giddy summer, and knew we’d be back. The Cyclones were now a part of our baseball lives. And honestly, going to Keyspan was sometimes more fun than a trip to Shea — it was both cheaper and cooler, it had better food, there was stuff to do before and/or after, and the games were typically a crisp two hours instead of a sometimes-soggy three.

The part that was new to us was assessing the players. It would be years before I’d understand the harsh reality of the lower minors: Each year’s Cyclones roster featured a handful of players considered real prospects and a bunch of teammates who were there to fill out the roster. The prospects would be given every opportunity to fail; the others would have to do extraordinary things over and over again to get noticed. It’s a caste system, and a cruel one.

For Emily and me, two players became emblems of that first summer.

One was John Toner, an outfielder with the endearing habit of looking over when the girls in the stands would yell for him. I wasn’t enough of a scout to assess Toner’s baseball abilities, but I’d been around long enough to see he was having the time of his life.

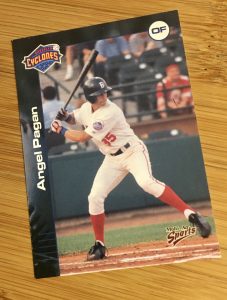

The other emblematic player was the Cyclones’ first heartthrob — a lithe, dark-eyed center fielder with a name borrowed from a shoegazer band you wanted your parents to hate. The girls screamed for Angel Pagan; so, in my own nerdy blue-and-orange way, did I. I was certain that he was the one, the Cyclone who’d solve the pitiless math of the minor leagues and show up one day at Shea. Pagan was going to be a star, and I was going to be able to point at him from the back of the mezzanine and tell people how I’d seen him play in a little park on the beach, not so long ago and not so far away, and now just look at him.

Which turned out to be true. Eventually. If you squinted a little.

Toner was back in Brooklyn the next summer, which we were yet to realize wasn’t a good sign; he was out of baseball by 2004. But Pagan kept going: Capital City, St. Lucie, Binghamton, Norfolk. In 2005 he hit .271 with 27 steals in a full Triple-A season. He was only 23; it looked like my dream might even come true a little early.

And then, in the offseason, the Mets sold him to the Cubs.

I was heartbroken — and seethed when Pagan made his big-league debut in Chicago in 2006. He was a part-timer as a Cub, plagued by both injuries and mental lapses, but I didn’t care. He’d been a Cyclone. He’d been meant to be a Met. Anyone could see that — except, apparently, the Mets front office.

And then, a miracle. The Mets reacquired him.

Pagan didn’t become a star in 2008 — in fact, he was lost for the year in July after he hurt his shoulder diving into the stands — but there he was at Shea, just like I’d imagined. (He even rehabbed briefly with the Cyclones.) And when the Mets made the move to Citi Field in 2009, so did he.

2009 — the year to which this profile belongs — was not a good year in Mets annals. We first heard the name “Bernie Madoff” and discovered what he’d done for but mostly to the Wilpons. Not just the country but the entire world was struggling to escape a horrific recession that had been set in motion by arcane investment instruments and the supposed wizards who’d invented them. The new park, emblazoned with the name of those suddenly shaky financial titans, felt more like a monument to Fred Wilpon’s Brooklyn childhood than a home for the actual baseball team he owned.

And the team? The one picked as World Series champs by Sports Illustrated after two heartbreaking finishes in 2007 and 2008? It was a goddamn dumpster fire. Daniel Murphy played left field like a soldier being shelled. In the home opener, Mike Pelfrey served up a home run to the immortal Jody Gerut on his third pitch and later fell down on the mound. Carlos Beltran forgot how to slide. Oliver Perez showed up looking like he’d eaten an entire ZIP code and soon had an ERA to match. Ryan Church missed third base out in L.A. Luis Castillo turned the last out of a win in Yankee Stadium into a walk-off error. Omar Minaya decided that the bizarre behavior of Tony Bernazard, the Mets’ VP of player development, was part of a sinister plot cooked up by beat writer Adam Rubin. David Wright was hit in the head by a fastball, which helped send his glittering career into a tailspin from which it never truly recovered. New acquisition Jeff Francoeur got with the program by hitting into a game-ending unassisted triple play. And the injuries, oh the injuries. Every day seemed to bring a new one: Johan Santana, Carlos Delgado, Wright, Beltran, J.J Putz, Jose Reyes.

If you weren’t there, count yourself lucky.

In a season like that, you take any bright spots you can find, and Pagan was one of them. He somehow avoided the Biblical plague of misfortune, got playing time and showed he deserved it: His final line for the season was a .306 average with 14 steals. The Mets, being the Mets, responded by reacquiring Gary Matthews Jr. for 2009. Matthews proved not to be the answer — it’s hard to play with a giant fork sticking out of your back — and Pagan took his job, then had a breakout year. He hit 11 home runs and brought much-needed speed to the club, stealing 37 bags and playing excellent defense in center. He may not have been the most consistent player — he was still prone to lapses on the bases and on defense, earning himself the nickname El Caballo Loco — but he was definitely exciting, turning a triple play and hitting an inside-the-park home run in the same game. (Alas, the Mets still lost.)

And so there we were — that first Cyclones heartthrob, playing center for the Mets. No, it wasn’t at Shea and there’d been that detour to the Cubs and the Mets were crummy and sometimes Pagan brought too much loco and not enough caballo, but it was at least close-ish to what I’d imagined. Remember those Family Circus cartoons where Jeffy gets sent on an errand and returns later than expected, with a tangle of dotted lines representing his distracted ramblings around the neighborhood? Kid still came home, right?

In 2011, though, Jeffy forgot about the quart of milk for Mom. Pagan got off to a slow start, reacted badly, was plagued by injuries, and alienated both teammates and management. There were highlights — most notably his walkoff homer against the Cardinals, nearly caught by Gary, Keith or Ron in the Pepsi Porch — but there weren’t enough of them, and in the offseason Sandy Alderson sent Pagan to the Giants for a much-needed reliable reliever, Ramon Ramirez, and a similarly dynamic/enigmatic outfielder, Andres Torres.

This time, I wasn’t heartbroken. The caballo/loco ratio was out of whack, and while I still felt affectionate about the original Cyclone who’d made good, I’d also decided Pagan was one of those players who’d benefit from a new clubhouse and new voices. Which turned out to be true — Pagan rebounded to garner some low-level MVP votes as the ’12 Giants won a title, then proved a useful player for them over several more seasons. (The trade was a disaster for the Mets, as Ramirez and Torres both imploded.) Eventually Pagan wore out his welcome in San Francisco too: When the team found itself in desperate need of outfielders in 2017, it was telling that they didn’t ink the guy they’d employed just the year before, the one who was unsigned and loudly advertising his availability. Pagan, by then one of the last of the Shea Mets, never did find a deal; his retirement turned out to be involuntary and more permanent than he’d imagined.

So what does all this mean? I’m tempted to conclude with a warning about how storytelling compels us to search for a moral even when it’s just a bunch of stuff that happened. But that feels both glib and cheap. Here’s a more worthy lesson: Baseball infatuations are part of being a fan, even if they aren’t yet supported by reality. There’s nothing at all wrong with that. Dreaming is free, to quote the philosophers Stein and Harry, and it’s to be celebrated and encouraged. But just remember that even those dreams that do come true might not exactly fit what you saw when your eyes were closed.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2008: Johan Santana

2012: R.A. Dickey

As a Mets fan who thinks Loveless by My Bloody Valentine may be the best album of the 90’s or is at the very least the best album ever by any band from Ireland, there is nowhere else I can turn for a line like “a lithe, dark-eyed center fielder with a name borrowed from a shoegazer band you wanted your parents to hate.” Brilliant Jason, you’re the only writer in the English language who could’ve written that (and I’m sorry I didn’t). Angel Pagan. Of course. Perfect band name, just have to pronounce Pagan differently. And the trade that led Sandy Anderson to think that a remark like “what outfield?” was so funny.

This series is great.

Thank you Dave, we’re both glad you’re enjoying the series!

Am I the only guy who keeps mixing up Angel Pagan with Endy Chavez?

Actually, I believe you are!

“Matthews proved not to be the answer — it’s hard to play with a giant fork sticking out of your back” – but he got an MVP vote only four years ago! How could this happen …!? Some 60 PA and 1 RBI. I know RBI aren’t the preferred metric to rank players, but at a certain ratio you just know the guy was no more useful than a half-eaten sandwich in a hole in Yonkers.

Always fascinating how the Mets always get the very worst out of half the players they touch. See: Matthews, Ramirez, Torres (sort of). While ’12 was the first year I had MLB.tv glued to my eyeballs, I didn’t even really remember Ramirez, who paled in comparison to the other countless horrors in that bullpen. Frank Francisco. Manny Acosta. Elvin Ramirez. Miguel Batista. Woof.

There’s a great video by Jon Bois about Jeff Francoeur on Youtube… I would provide a link, but Youtube appears to be blocked now in the office. Good times.

I know it. And you’re right, it is great!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1VtKxqbwpm0

Gary Matthews Junior was the first of the Mets’ Juniors of Doom, the others being Eric Davis Junior and the execrable John Mayberry Junior. I was torn between two theories – a, the Wilpons thought they were trading for their dads, or b, the Wilpons thought they were trading for Ken Griffey Junior. (Then again, that might be too sarcastic a take even for a Met blog comment section.)

Garry Matthews Jr. made one of the best, if not THEE BEST, catches in baseball history, robbing someone of a homer, leaping above the wall with his back to the plate.

Google it on YOUTUBE and you will not believe it!

Weirdly, when I visited the Rangers’ stadium last year, I got a bobblehead of this moment.

[…] Lost and Found » […]

Forgot Sandy Alomar Junior. I knew there was another member of the fraternity.