Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Championship teams aren’t meant to last. When the New York Mets returned to Shea in April 1987 to defend their second title, supersub Kevin Mitchell was a Padre, World Series MVP Ray Knight was an Oriole, reliable pinch-hitter Danny Heep was a Dodger, oft-forgotten reliever Randy Niemann was a Twin, and backup catcher Ed Hearn was a Royal. Twenty-four Mets had been on the active roster when Jesse Orosco fanned Marty Barrett; more than 20 percent of them, it turned out, had been wearing a Mets uniform for the last time when they vanished into the pile near the Shea Stadium mound.

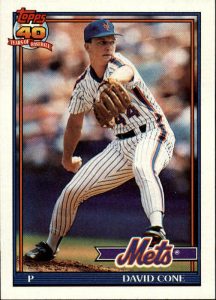

Hearn was a late subtraction, traded at the end of spring training (along with Rick Anderson and future recidivist Met Mauro Gozzo) to the Royals for a pair of unknowns: Chris Jelic and a rookie pitcher named David Cone. At the time, it seemed like one of those shrug-your-shoulders dog-and-cat trades, but with a side of sentimental melancholy: Hearn, nicknamed “Ward,” had filled in admirably for an injured Gary Carter that summer and seemed on his way to being a cult player and fan favorite.

It turned out to be one of the all-time steals in franchise history. Injuries ruined Hearn’s career, while Cone became the next great Mets hurler. By 1988, when Cone won 20 games as co-ace of the rotation, the trade seemed downright unfair. The Mets were a playoff-bound juggernaut; surely they had enough superb starting pitchers without fleecing other clubs out of theirs?

Cone would be a mainstay of the Mets rotation, then return to the city for a glorious run with the Yankees, making himself one of Gotham’s universal fan favorites. (He’s been a familiar face on the YES Network for some time, which we’ll reluctantly forgive.) He’d also prove an athlete who could handle the biggest of towns: open with fans, honest with the media, and no stranger to the far side of midnight. (This Sports Illustrated article, from ’93, is an excellent deep dive into Cone’s psyche that doesn’t shrink from examining his run-ins with tabloids and appearances in police reports.)

But in the beginning, his arrival in New York seemed more like a nightmare than a dream come true.

Cone was a Kansas City kid, raised in a blue-collar neighborhood by a tough-minded travel agent and a mechanic who saw success in sports as a way to ensure their children got the best possible education. (They also demonstrated where Cone got his quirky perspective, though — the Cone children’s backyard Wiffle Ball field was sometimes called Conedlestick Park.) Drafted by the Royals in 1981, Cone made his debut for his hometown team five years later. His first appearance on a big-league mound came in relief of Bret Saberhagen, which strikes me as spooky, given their similarities. At their peaks, both Cone and Saberhagen had more plus pitches than their catchers had fingers, along with a talent for improvising on the mound, and you wondered how they ever lost a game.

Cone was more serviceable than star in his first go-round, still trying to overpower hitters rather than outthink them. But he’d learn during winter ball, and reported to spring training in 1987 armed with two new pitches: a sidearm “Laredo” slider taught to him by Gaylord Perry and a split-finger fastball. Cone made the ’87 Royals rotation, only to be traded to the Mets on March 27.

He was convinced he’d be stuck in Triple-A, but with Dwight Gooden felled by cocaine, Cone began the season with the big club. He was coming into his own as a starting pitcher and a clubhouse presence in late May, when he broke his pinky bunting against Atlee Hammaker of the Giants. He’d be out until August, at which point everything that could go wrong for a Mets pitcher pretty much had — including Tom Seaver, last seen thankfully inactive on the Red Sox bench in the ’86 Series, reporting for comeback duty but then retiring for real after getting lit up by Barry Lyons. The Mets won 92 games, which was valiant but insufficient, but Cone had found he liked New York. He’d also grown as a pitcher, with Ron Darling helping him refine that splitter into a deadly weapon. (Cone would keep tinkering with the pitch, making another advance thanks to the tutelage of original Met Roger Craig.)

And oh my goodness did I love him. Cone was slim bordering on undersized — media guides generously listed him as 6’1″ — and bore an odd resemblance to a rather different hero of mine, Luke Skywalker. But while he wasn’t burly, he had the classic mechanics of a power pitcher and had honed them to near-perfection. His right hip was the focal point around which his arms and legs seemed to revolve, with no wasted motion. Cone has said Luis Tiant was his inspiration as a kid, and you can see that — Tiant’s famous for his hesitation and the turn of the back, but that obscures how tight and coiled his motion was. Plenty of power pitchers look impressive on the mound but arrive with mechanics that make you cringe because you can almost hear things grinding and fraying in their shoulders and elbows, but Cone looked like a gyroscope, from the way he loaded his arm down near his hip to the finishing, energy-dissipating kick of his right leg. It was like an engineer and an artist had collaborated to create the Platonic ideal of a pitcher.

Even Cone’s mistakes were mostly endearing. There was the famous play against the Braves where a livid Cone argued so vociferously with the first-base umpire that two enemy runners came home to score while Gregg Jefferies frantically tried to get his pitcher’s attention. I’ll even include the mishap that arguably cost the Mets a return to the World Series. Cone had written for his high-school paper and had a rapport with the beat writers, even joining them on occasion for pickup basketball games. In the ’88 playoffs, Bob Klapisch of the Daily News gathered Cone’s impressions for a ghostwritten column. Overamped after the Mets’ wild Game 1 victory, Cone compared Dodger closer Jay Howell to a high-school paper. Klapisch printed it, and Tommy Lasorda turned the unwise column into a rally cry, covering clubhouse bulletin boards with it and doing everything short of wrapping himself in the flag to protest this assault on Dodgerdom, fair play and the very idea of America. It worked — the vengeful Dodgers drove a rattled Cone from the mound in the second inning of Game 2, the Mets fell apart in Game 7, and I became one of the only people in America who watches Kirk Gibson‘s legendary home run with disgust about what might have been.

Remember that in ’88 athletes lied with a brazenness now characteristic of presidents; more often than not, a baseball player who’d said something stupid would blandly say he’d been misquoted, which too many fans then as now automatically believed. Cone didn’t do that; he owned what he’d done instead of letting Klapisch take the blame, and apologized to Howell. Three years later, cameras caught Cone and Buddy Harrelson arguing furiously in the dugout. Harrelson, a superb coach and baseball lifer but out of his depth as a manager in New York, tried to get Cone to lie about what had happened. Cone refused. The Mets clubhouses of the early ’90s were snakepits crawling with surly malcontents, arrogant and thin-skinned louts, and paranoid backstabbers, but Cone remained a standup guy. (And let’s throw in his sense of humor, best shown off in an Adidas ad that featured Yankee fans helping Cone safeguard his rehabbing arm.)

The Mets traded him in the miserable final weeks of 1992 to the Blue Jays for Ryan Thompson and Jeff Kent. (Like that clubhouse needed another socially inept sourpuss.) Cone won a World Series ring, while admitting that he felt like a rent-a-player, came home to Kansas City and won a Cy Young, was shipped back to Toronto after proving too outspoken for ownership’s tastes during the ’94 strike, and then returned to New York for the Yankees’ 1995 stretch drive. He arrived as a mercenary but would leave as an icon, winning four more rings with the Yankees, battling through an aneurysm that threatened to end his career, and pitching a perfect game on a day in which Don Larsen had thrown out the ceremonial first pitch, which is the kind of marvelous absurdity baseball seemingly has in inexhaustible supply.

A dislocated shoulder reduced Cone to a cameo in the 2000 Series against the Mets, pitching just five pitches, but they came in a crucial spot — he retired Mike Piazza in Game 4 with the Yankees clinging to a 3-2 lead. Then he was gone again, pitching for the Red Sox in ’01. His most notable start that year came against Mike Mussina, who’d replaced him in the Yankees’ rotation; with the score 0-0 in the top of ninth, Cone surrendered an unearned run. In the bottom of the inning, Mussina won the game but lost his bid for a perfect game with two outs and two strikes.

Cone sat out 2002, but still felt the pull of the game. Al Leiter and John Franco coaxed him into a comeback with the Mets for 2003 — the year he represents in our series, though it was his least successful campaign as a Met.

Cone, now 40, made the team and got off to a great start, pitching five scoreless innings against the Expos on April 4 with the loyal Coneheads in the stands to cheer him on. This time around, he was wearing 16 in honor of Gooden — another thing I loved about Cone was that uniform numbers meant something to him, as witnessed by his donning 17 for Keith Hernandez. (His original number, 44, is pretty damn cool too.)

Alas, the good times were not to last. Cone’s arm was sound, but the hip he used as a fulcrum for that perfect windup was worn down by decades of use. He went on the disabled list in late April, came back a month later and pitched two innings in relief in Philadelphia, the same place where he’d struck out 19 Phillies on the final day of the ’91 season, despite staying out all night and fearing he might be arrested midgame. (A woman had accused Cone of rape; Philadelphia authorities decided the charges were unfounded.) Cone pitched two innings, giving up a home run to Placido Polanco and exiting after coaxing a double-play grounder from Jason Michaels.

The next morning, Cone could barely limp across his hotel room. Like many a ballplayer, he’d stayed too long at the fair, and his body was telling him it was time to go. He retired, his roster spot going to 42-year-old Franco, who’d had Tommy John surgery and last been seen at the tail end of 2001, giving up a grand slam to Brian Jordan that still makes me want to lie down in a dark, quiet room for several hours. Franco mock-apologized for forcing Cone out; Cone joked that it was time to give the young guys a chance.

Two days after Cone’s final appearance, the fans at Shea responded to the announcement of his retirement and a video tribute with a standing ovation. Cone wasn’t there to hear it; he’d gone home to have dinner with his wife. He’d written a glittering story — 194 wins, 2,668 strikeouts, five All-Star nods, five World Series rings — but that story was over. Seventeen years later, though, I can close my eyes and still see him plain as day. He’s eyeing the hitter, thinking what he’s going to do with this pitch — and, if need be, with the one after that. He’s got a lot of options to choose from, and if any of them should prove lacking, well, he’ll think of something. And there’s no way I’m betting against him.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

Do you remember the vivid and cringe-worthy headline in the NY Post, “Weird Sex Act in Bullpen” about David Cone interacting with young female fans in the outfield?

Of course. The tabloid rumor that launched a thousand cartoons.

Conie was involved in both one of my favorite and least-favorite trades ever. Nothing to talk about the first one – maybe the most lopsided trade in Mets history in their favor (except possibly the Piazza deal). As for the second one, I saw it as the last in the casting-off trades of great late-’80’s Mets players, which started with the awful Juan Samuel deal, and swapping the likes of Ron Darling, Mookie Wilson and Wally Backman for virtually no one (not to mention getting literally no one for free agents Hernandez, Carter and Strawberry). The Cone deal was the final nail in the coffin, despite Jeff Kent turning out to be possibly the best hitting Mets second bagger this side of Edgardo. Didn’t matter. The best Mets team ever was officially toast.

By the way, I liked Eddie Hearn; but to be honest, aside from George Foster and Tim Corcoran, pretty much every ’86 Met was a cult icon. At least as far as I’m concerned.

[…] Staub 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1994: Rico Brogna 2000: Melvin Mora 2002: Al Leiter 2003: David Cone 2008: Johan Santana 2009: Angel Pagan 2012: R.A. […]