The agate type that used to fill newspapers’ TRANSACTIONS boxes and for all I know still do can change everything — about your team, about the players within, about the course of your expectations and satisfaction as fan. While the Hot Stove barely simmers, Kyle Tucker rumors notwithstanding, I’d like to take this opportunity revisit a few picas worth of Mets transactions through time.

In a particular but not chronological order, nitty-gritty details courtesy of Baseball-Reference…

January 13, 2005: CARLOS BELTRAN signed as a free agent with the New York Mets.

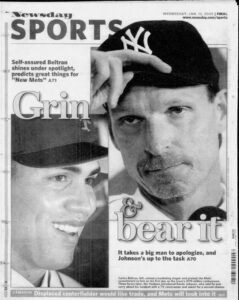

January 13 is the date BB-Ref has for Carlos Beltran [1] signing with the Mets, meaning happy twenty-first anniversary! But it wasn’t January 13, so happy twenty-first-ish anniversary! Maybe January 13 was when the ink officially dried on the contract, but it was learned Beltran was becoming a Met as of the early morning hours of January 9, 2005, shortly after the Jets upset the Chargers in the AFC Divisional playoffs. This, too, was an upset. Beltran seemed likely to either stay in Houston or get paid by the Yankees. Yet Carlos showed up at Shea to join the “New Mets” on January 11, the one day after the Yankees’ consolation prize, Randy Johnson, roughed up a cameraman who had the audacity to film him. Both New York arrivals were on TV that day and in all the papers the next; ours went smoother. By January 13, Beltran’s signing was no longer a bulletin, though the excitement was still fresh. We — the Mets — had lured the biggest, shiniest free agent on the market into our lair. It took a big, shiny, unMetlike offer, but such was tendered and accepted.

Just like that, Carlos Beltran was a New York Met. Just like that, everything Carlos Beltran did or didn’t do became our business. Just like that, we worried about Carlos Beltran, maybe in generous personal “I hope he’s all right” terms, but mostly in transactional “I hope he gets going/stays hot” terms. It is the Transactions box after all.

In 2005, the first year in which Carlos Beltran became our business, business was so-so. Then, from 2006 until he got hurt in the middle of 2009, business mostly boomed [3], even if things came to a chilling standstill once or twice. He returned to health after about a year and kept going/stayed hot, straight to the moment in 2011 when it seemed to everybody’s benefit to send him on his way. The seven-year contract was about to be up, the Mets were relatively down, and a Beltran could you get you a piece of future. Carlos by this point had put together a very nice Met past, enough to earn him a spot in the team’s Hall of Fame.

On January 20, 2026, the Baseball Writers Association of America vote for the big Hall of Fame will be announced. Carlos Beltran is the institution’s leading candidate. Those who track the publicly shared ballots (publicly shared partly for transparency’s sake and partly because if you’re going to fill column inches amid the Cold Stove portion of winter, how can you pass up a hardy perennial of a topic?) have calculated Beltran is running way past the 75% barrier [4] required for Cooperstown entry. Even if those BBWAA members who are shy about revealing their choices are not as pro-Beltran as their brethren, the Hall appears his imminent destination. Not a surprise if you watched him for his seven Met seasons. From 2005 to 2011, we had ourselves an every-tool craftsman who, all things considered, made the Mets’ investment of $119 million worthwhile. We not only got ourselves a Silver Slugger, a Gold Glover, and perception-changer, we are on the verge of saying we got ourselves a future Hall of Famer whose Met experience is hardly incidental to the qualifications inspiring all those check marks and X’s.

You can’t always say that, no matter how tantalizing the Transactions box looks the instant it is published.

February 10, 1982: GEORGE FOSTER traded by the Cincinnati Reds to the New York Mets for Greg Harris, Jim Kern, and Alex Treviño.

My brother-in-law goes by the familial code name Mr. Stem, denoting that his level of interest in the Mets is the inverse of mine. Yet Mr. Stem comes through every December 31 for my birthday [5] with what he believes are throwaway baseball items. He sees something old somewhere, he scoops it up, he sticks it in a box — after wrapping it exquisitely and numbering it so the entire presentation can be expertly choreographed — and he sends it to me for video unveiling on New Year’s Eve. This is part of our family tradition every December 31 ever since he and my sister moved to the West Coast. That and me good-naturedly (I swear) reminding them that the last year they lived back East, they sent Stephanie and me home well before midnight because they wanted to go to bed.

The arcana he secures is utterly random. Mr. Stem has a narrow frame of baseball reference, but his instinct for the utterly eclectic is so razor sharp that it could be Razor Shines [6]. Pulp novels from the 1940s. Statistical volumes from the 1960s. Out-of-print histories inevitably prefaced with “you probably already have this”. And, once in a while, something that makes me go SQUEE!

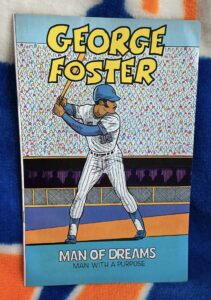

This past birthday, Mr. Stem sent me a comic book with the title George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose.

SQUEE!

GEORGE FOSTER [7]!

A COMIC BOOK VERSION OF GEORGE FOSTER!

GEORGE FOSTER IN A METS UNIFORM ON THE COVER!

GEORGE FOSTER SWINGING A BAT THAT ISN’T HIS TRADEMARK BLACK BAT, DESPITE THE FACT THAT THIS COMIC BOOK IS PUBLISHED BY GEORGE FOSTER ENTERPRISES, INC., THUS YOU’D INFER ACCURACY WOULD BE A GIVEN!

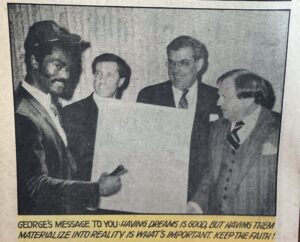

GEORGE FOSTER ACCOMPANIED BY FRED WILPON, NELSON DOUBLEDAY, AND FRANK CASHEN IN THE COMIC BOOK’S FINAL PANEL, NOT DRAWN LIKE THE REST OF THE COMIC BUT PHOTOCOPIED FROM HIS PRESS CONFERENCE WHERE HE’S SIGNING THE CONTRACT THAT’S GONNA MAKE HIM A MET FOR THE NEXT FIVE YEARS, THE MOMENT WHEN EVERYTHING ABOUT GEORGE FOSTER BEING ON THE METS WAS SUCH AN UNSULLIED POSITITVE THAT YOU JUST HAD TO GO OUT AND PUBLISH A COMIC BOOK ABOUT IT!

“If I knew that was going to be such a big hit,” Mr. Stem observed, “I would have saved it for last.”

It was my party and I’d SQUEE! if wanted to. You would SQUEE!, too, if it happened to you.

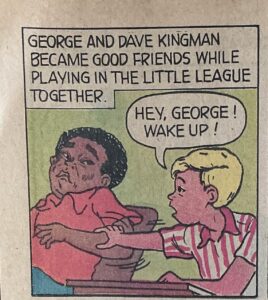

[8]The beauty part of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, besides its existence; its sense of opportunism (revisited four years later when Foster foisted “Get Metsmerized [9]” on the rap-listening Mets fan community); the panel that taught us “George and Dave Kingman became good friends while playing in the Little League together”; and the heroism with which it imbues its lead character as he commences his life journey of learning to take math class seriously so he can calculate his batting average between belting home runs, is its timing. Not just the timing of appearing in my hands weeks after the departures of so many Citi Field stalwarts pushed me into a Metsian funk, but the timing of its publication. George Foster Enterprises, Inc., hustled this comic onto the market in 1982. In 1982, we were ripe for believing George Foster’s purpose meshed with our dreams of making the Mets an overnight contender. We’d be disabused of those dreams before 1982 was over.

[8]The beauty part of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, besides its existence; its sense of opportunism (revisited four years later when Foster foisted “Get Metsmerized [9]” on the rap-listening Mets fan community); the panel that taught us “George and Dave Kingman became good friends while playing in the Little League together”; and the heroism with which it imbues its lead character as he commences his life journey of learning to take math class seriously so he can calculate his batting average between belting home runs, is its timing. Not just the timing of appearing in my hands weeks after the departures of so many Citi Field stalwarts pushed me into a Metsian funk, but the timing of its publication. George Foster Enterprises, Inc., hustled this comic onto the market in 1982. In 1982, we were ripe for believing George Foster’s purpose meshed with our dreams of making the Mets an overnight contender. We’d be disabused of those dreams before 1982 was over.

As I descended slightly from my instant euphoria over holding and leafing through a copy of George Foster: Man of Dreams, Man With a Purpose, I attempted to give my sister and her husband a capsule Metsplanation of the significance of trading for George Foster and shelling out the enormous bucks Cincinnati no longer wished to shell in ’82, which is to say why this comic book got me right in the feels. The Mets, I detailed broadly, had never acquired a player of his caliber, at least not one still more or less in his prime. Foster, I continued, was regularly among the league leaders in all kinds of categories from which the Mets were usually absent. He’d been an MVP not that long before. He was an intrinsic element in something called the Big Red Machine, a contraption that had won championships.

“So what happened when he came to the Mets?” my sister asked.

“He fell of a cliff. Was never as good as he’d been with his old team. Became such an object of disdain that fans outside Shea, when they recognized the stretch limo he took to the ballpark, pelted it with rocks and garbage.”

“Doesn’t that always happen?” A Met trade for a superstar going south, she meant.

[10]I figured I had about thirty seconds more of their attention before their interest on the subject waned and they’d want me to unwrap the next tchotchke, so I condensed it to “not always, but enough to leave that impression.”

[10]I figured I had about thirty seconds more of their attention before their interest on the subject waned and they’d want me to unwrap the next tchotchke, so I condensed it to “not always, but enough to leave that impression.”

Left uncited in my summary was the time the Mets traded a superstar of their own and could be said to have gotten the better of the deal. The catch was their transactional victory didn’t emerge as a certifiable Met win for approximately a third of a century.

March 27, 1987: DAVID CONE traded by the Kansas City Royals with Chris Jelic to the New York Mets for Rick Anderson, Mauro Gozzo, and Ed Hearn.

No, George Foster didn’t resemble a comic book hero as a Met, but he was an important building block in who the Mets were going to become. And after the massive disappointment of 1982, he proved intermittently productive over the following three seasons and helped lift the Mets to their outstanding start the year after that, 1986. Then the cliff beckoned again. He fell off it for good by August, no longer contributing to the ballclub that had grown up around him and showing himself unwilling to accept a reduced role now that he was no longer a Man With a Purpose at Shea.

During the years in between the trade for Foster and the release of Foster, the Mets made mostly outstanding trades. I didn’t get into that with the Stems, but we know they did. We also know that on the other side of the championship the Mets won once Foster talked his way out of town, they had one more dynamite deal up their sleeve.

I’m not the only person with a Mets connection who celebrates a birthday right around New Year’s. David Cone [11] was born two days after me. His Mets connection might be stronger than mine.

True, I beat Coney to this earth by approximately 48 hours and to a deep and abiding interest in who the Mets might trade for by many years, but it was me being all “we got who for Ed Hearn?” as Spring Training 1987 wound down, rather than David Cone being all “what do you mean there’s a Mets fan two days older than me who has no prior awareness of my potential as a starting pitcher?” Cone didn’t know who I was when he came over from Kansas City with eleven games’ worth of big league experience, but I learned about him plenty in the seasons to come. Especially in 1988, when he won 20 games for the division-winning Mets. And 1990, when he shut down the Pirates in the final Big Series of the era (9 IP, 1 ER, enormous W). And 1991, when he led the National League in strikeouts for a second consecutive year, capping it with 19 on Closing Day in Philadelphia. And 1992, when he went to his second All-Star Game as a Met. Hearn the backup catcher for Cone the budding ace worked out very well for the Mets. Only problem was Cone, 28 and on the eve of free agency, would now want to get compensated commensurate to his achievements as he approached the next segment of his career.

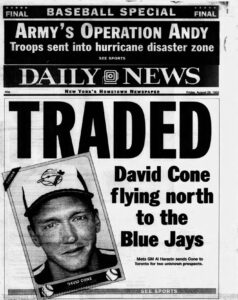

August of 1992 found the Mets nearly two years removed from that final Big Series of the era. Despite the future former ESPN commentator’s [12] electric arm, magnetic presence [13] (maybe sometimes a little too magnetic [14]), and ongoing superbness, the Mets had faded from contention in 1991 and imploded altogether amid an on-the-fly reloading the next season, one of those periods when it becomes reasonable to ask, “Doesn’t that always happen?” Whether it does or not, Al Harazin, the GM who succeeded Frank Cashen, decided to take a different approach. Instead of trading for an established star, he’d trade the one he had who was having a helluva year to a formidable team with championship aspirations..

August 27, 1992: JEFF KENT traded by the Toronto Blue Jays with a player to be named later to the New York Mets for David Cone.

We are deep enough into January to take a cue from Larry David [15] and move beyond wishing one another a Happy New Year. The residue from my birthday and David Cone’s birthday has evaporated. We look forward to later January things as January gets going. We, as baseball fans, look forward to the Hall of Fame voting being announced, particularly if we have a rooting interest.

As baseball fans we root for greatness to be properly recognized, but that’s not really our rooting interest when it comes to the Hall of Fame. We root for players we liked when they played and, I’ve come to conclude, we root to tell the Hall of Fame voters they don’t know what the hell they’re doing. On January 20, when the envelope is unsealed on the MLB Network, we might very well cheer that Carlos Beltran has been elected on his fourth ballot; we might offer polite applause if Bobby Abreu or Francisco Rodriguez shows any sign of momentum; we might feel our heart warm if David Wright remains eligible to appear again next year; we will likely be curious to see if Daniel Murphy or Rick Porcello received as much as one vote; and we will certainly be sure somebody is getting overlooked or, worse, overvalued.

The Hall of Fame attempts to honor baseball’s legends, but I’ve become convinced the main reason it’s there is so fans can tell anybody who’ll listen that they’re right and most everybody else with an opinion slightly different from theirs is a clod. Which reminds me — the list of no longer insightful phrases I hope transmit a faint shock to the fingertips of anybody who types them, so as to discourage their rote repletion, now includes:

• “we root for the laundry”;

• “this is why we can’t have nice things”;

• “if the Wild Card existed then, we would have been in the playoffs every year”;

• and, especially in the weeks surrounding New Year’s Eve/Day, “…more like Hall of Very Good”.

To prepare us in our self-assuredness that we’re right and they’re wrong, the Hall of Fame gives us a test run by announcing its Era Committee decision in December. Different Eras are Committee’d in different Decembers. In December 2025, the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee convened. That’s the one that considers players who shone most brightly from 1980 forward who are no longer eligible to be on the writers’ ballot. The other Era Committee is the Classic Baseball Era Committee, covering the days before 1980. There was a lot of classic baseball played from 1980 forward, and the 1980s aren’t particularly contemporary at this time, but never mind that. Those are the names. And the committee with the contemporary name elected one new Hall of Famer last month.

[16]The guy we got for David Cone. Well, we got two guys for David Cone. One was initially a player to be named later, whose name wasn’t Classic or Contemporary. It was Ryan Thompson. High hopes were attached to Ryan Thompson. They weren’t fulfilled, not when he was a Met, not after he was a Met. It happens. They could have waited to name Ryan Thompson all they wanted. He wasn’t making the Hall of Fame.

[16]The guy we got for David Cone. Well, we got two guys for David Cone. One was initially a player to be named later, whose name wasn’t Classic or Contemporary. It was Ryan Thompson. High hopes were attached to Ryan Thompson. They weren’t fulfilled, not when he was a Met, not after he was a Met. It happens. They could have waited to name Ryan Thompson all they wanted. He wasn’t making the Hall of Fame.

Jeff Kent [17], on the other hand, is a Hall of Famer. The Contemporary Baseball Era Committee says so, and who are we to argue with such a thoroughly named committee? When the news of his 1992 acquisition thrust itself onto my radar, I was being all “we got who for David Cone?” The answer was never — not in the immediate aftermath of the news nor at any juncture of the parts of five seasons he was a Met — “we got a future Hall of Famer for David Cone!” But son of a gun, that’s exactly what we did.

Kent, whom the Baseball Writers Association of America resisted electing for ten winters, was on the committee ballot alongside seven other players. The eight of them all had credentials making them worthy of a second thought, which is the whole idea of these committees. The BBWAA has the definitive word, but not necessarily the final one. Not enough writers opted to ink in an X or check mark next to Kent or the other seven — Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Carlos Delgado, Don Mattingly, Dale Murphy, Gary Sheffield, and Fernando Valenzuela — thus none of them was ever elected during their prime eligibility period. Writers can miss things. Thus, committees, despite their own capability for missing things (like Keith Hernandez’s qualifications), convene and debate and vote.

In December, they voted for Kent in numbers large enough to immortalize him. They voted for Delgado somewhat, but not quite enough to push our former first baseman (another ex-Blue Jay) over the top. This Carlos’s level of support made for a nice refutation of the writers who ignored him his one year as a BBWAA candidate in 2015, even if it was insufficient for 2026 induction. Murphy and Mattingly, arguably the best players in their leagues at their peak, also won measurable if inadequate support. Bonds and Clemens, inarguably the most prolific hitter and pitcher of their and perhaps all time, didn’t get any reported votes, for presumably the same reasons the writers never came close to selecting them. Nothing of note for Sheffield, one of the most dangerous hitters I ever watched, including when he was in his Met twilight; nothing, either, for Valenzuela, a huge star and a great pitcher.

It could be argued Fernando didn’t do what he did so marvelously long enough. It probably was when the committee met. Same for Murphy and Mattingly. The arguing, official and otherwise, seems to the be the point of every aspect of the Hall of Fame selection process. I couldn’t stand Roger Clemens, but I wouldn’t argue he wasn’t a Hall of Famer in terms of performance, however toxically he put together a good bit of it. That’s what makes me less than ideal as a Hall of Fame consumer. I’m not much for arguing against the merits of great baseball players. If they got far enough to be considered anew after the writers said “nah,” they probably had a lot going for them as players. The existing plaques wouldn’t fall down in shame if a new one was added for any of them. Even — yeech — Clemens.

It takes a ton of retrospect to apply the L-word to Jeff Kent from when he was a Met. I don’t know that I’ve stockpiled enough. If I call him a flagship Met of the years when the Mets were sinking, it comes off as an unintentional insult. Still, I think of him as kind of the personification of his Mets at their striving best. There were days and nights, you thought those Mets could get better. Those were days and nights when you grabbed a peek at Kent, who was 24 when was traded to us, and thought, maybe, just maybe, we can build a little around this guy. And even if we can’t, he’s already here and he’s not really the reason we’re not great.

If it was somewhere between 1992 and 1996 and you were a Mets fan, that’s pretty much what love was.

At his Met best, which covered roughly the middle of 1993 to the middle of 1994 (slashing .302/.362/.511 over the 162 games the Mets played between 6/22/93 and 6/19/94), he was an All-Star caliber second baseman, despite not being named to either year’s squad. He’d get his NL due later, in another uniform, though by then, I’d be feverishly punching out holes next to second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo’s name in my personal quest to see my favorite Met start ahead of everybody else. Fonzie I absolutely loved. He and his team as one century became another inspired torrents of passion.

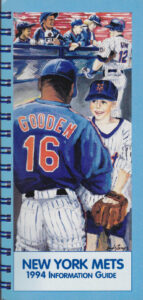

Kent I liked OK when he was going well when he was a Met. He surely had his moments. As illustrated in the above paragraph, he had a solid season’s worth. During the second half of 1993, he set a foreshadowy second baseman home run record (most in a single season by any Met playing the position — 20 overall, 19 in games he manned second, eventually broken by Edgardo). His potential was legitimately encouraging to fans and as well as management. With the Mets aiming to grope their way out of last place and their image-makers wishing to communicate their present included glints of sunlight, they included Kent alongside legend-in-residence Doc Gooden on the cover of their 1994 media guide, Norman Rockwell-style. In the foreground Gooden is signing an autograph for a delighted kid. Behind them is Kent, doing the same for a couple of more kids. It was the Mets’ way of saying we have players you’ve loved and players we think you might like. Not pictured: any Met throwing firecrackers at anybody. The Mets may not have been ready to vault out from under .500, but they were gonna be fairly affable. [18]

[18]

They were gonna be better once ’94 got going, and not only because they couldn’t have been much worse than their 59-103 selves. No Met started the new season hotter than Kent, who earned himself NL Player of the Week Honors for the second week of the year, which encompassed five games — but what games! Six homers! Thirteen RBIs! Start the All-Star voting ASAP! If nothing else, Jeff was making some early takes on the trade that brought him to Flushing look vastly premature and more than a little myopic. To be fair, everybody was in shock at the end of August in ’92, and few were in the mood to learn much about the new kid in town.

Still…

“Good Lord. I can’t believe we didn’t get a proven major league player in return.”

—Dave Magadan

“Ever since they let Straw go, nothing surprises me anymore.”

—Gooden

“They had someone who’d proven he could make it in New York, and they let him get away.”

—Cone himself, though he might have been biased

Kent didn’t keep up the offense as 1994 wound down and then disappeared due to a strike. When baseball re-emerged in 1995, the infielder who made strides beyond the assessment that followed his acquisition — “regarded as a solid and versatile player…but not a spectacular one,” per Tom Verducci in Newsday — failed to progress. And any gestating thoughts I (or any Mets fan) might have incubated about Jeff Kent growing into a future Hall of Famer likewise didn’t materialize.

Tom Seaver came along and created a Hall of Fame résumé right before our eyes. Nolan Ryan went to Anaheim and did the same, packing with him what surely somebody between 1966 and 1971 referred to in Queens as Hall of Fame stuff. Willie Mays was Willie Mays. Gary Carter was on the road to Cooperstown the day he became a Met; the championship he helped lead us to allowed him to access the express lane, even if the writers made him sit through six ballots’ worth of traffic. Eddie Murray, who did not elevate the Mets by force of his bat and personality, would pay no penalty for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, having already stamped his first-ballot ticket in Baltimore.

Mike Piazza was a megastar who became larger than life as a Met. Rickey Henderson was on Mount Rickey forever. Roberto Alomar and T#m Gl@v!ne, not personal favorites, couldn’t be denied their destiny. We knew they were “future Hall of Famers,” which made their middling fits (to put it kindly) all the more vexing. Pedro Martinez, who became a personal favorite while in our midst, might as well have signed kids’ programs with “HOF” after his name the moment he came here. Billy Wagner someday becoming a Hall of Famer didn’t seem illogical as he manned the Met mound, even on those occasional afternoons when saves eluded his grasp.

But Jeff Kent? While he was a Met? From August 1992, when he was not yet any kind of name outside Toronto, to July 1996, when it seemed fait accompli that he’d be dealt to somebody somewhere sometime soon (he’d been moved off second base and marooned at third because Jose Vizcaino had been bumped from short and transferred to second in the interest of making room for Rey Ordoñez’s magic glove), there was no inkling that Jeff Kent of the New York Mets would become Jeff Kent of the Hall of Fame. Not even in National League Player of the Week mode, as delicious a week as that was. Not even when the 1995 Mets finished on an unforeseen upswing, going 34-18 and raising unreasonable hopes for 1996. Late ’95 was a whale of a time to be a hopeful Mets fan. Everybody was youthful, everybody was doing something promising.

Unfortunately, that was also the year when a meeting among Mets fans was called and it was decided we were going to mostly boo Jeff Kent as long as he was around (and really let him hear it should he ever go). His pre-strike gleam wore off. The better-angels side of his nature — I seem to recall a “Kent’s Kids” sign over the Picnic Area seats, and he was a spokesman for the No Small Affair organization that served disadvantaged youngsters — didn’t cut much ice against a personality that didn’t mesh with the Hootie & the Blowfish vibe the latest youth movement evinced. “How ’bout them baby Mets?” John Franco was heard to shout with a little love and some tenderness after one particularly uplifting triumph. Those were the Mets of Pulse and Izzy and Rico and Huskey and rookie Fonzie. Kent was among them as well if not exactly of them.

The young Mets played beautifully over the last two months of 1995. Yet amid the proto-OMG emotion of that late summer, Jeff Kent, 27, seemed atonal in relation to the whole “Hold My Hand” arrangement. As that season finished, Marty Noble described Kent’s status for the future as “unclear,” citing “his failure to drive in runs [as] a critical factor in the team’s poor early performance. He made a comeback, but it has been gradual and rarely conspicuous. And the club is quite aware that his square-peg personality grates on his teammates.”

Fair or not, the last couple of years of Kent as a Met and Met mope (the Jeff Can’t phase) set the stage for the reception we’d give him as an opponent, including two postseason interactions — in 2000 and 2006 — when his presence as a losing Giant and then losing Dodger landed as a fringe benefit within Met Division Series victories.

But there he is. Hall of Famer Jeff Kent, no matter what we were thinking when he was New York Met Jeff Kent. For his part, I get the idea that Kent stopped thinking about us a long time ago. He was gracious enough to join Jay Horwitz on the alumni director’s podcast shortly before the Contemporary Era Committee voted, and he mostly pleaded amnesia as regarded his Met years, save for liking Jay and appreciating Dallas Green.

Y’know what, though? Good for that mope of a Met making the Hall. I love in 2026 that the dreadful 1993 Mets were studded by two Hall of Famers, Murray and Kent. There was nothing that felt immortal about attending sixteen games at Shea that season, but one did come away from the whole experience feeling baseball-bulletproof. If this kind of year can’t kill me, nothing can — and I got to see two Hall of Famers over and over!

July 29, 1996: CARLOS BAERGA traded by the Cleveland Indians with Alvaro Espinoza to the New York Mets for Jeff Kent and Jose Vizcaino.

Murray was gone before 1994, off to Cleveland to have the kind of effect — leading a younger team toward the playoffs — he never had in Flushing. Kent carried the Cooperstown banner forward on his own at Shea. Not that it was visible in real time, but we now know it was there, clear to the day he and Vizcaino were traded to Cleveland for former All-Star Carlos Baerga [19] and utilityman Alvaro Espinoza (missing the Baltimore-boomeranged Murray by about a week), a classic trade that didn’t seem to help anybody in the short term. The Indians went to the playoffs with Kent and Vizcaino, but they were going, regardless. Then they got rid of their ex-Mets and kept winning. Cleveland was a way station for more than one young or young-ish Met who’d pick up steam elsewhere. Jeromy Burnitz as a Tribesman in 1995 didn’t contribute much to their successful pennant push. He had to be shipped to Milwaukee to attain the stardom Dallas Green was too impatient to cultivate.

It took a second trade, to San Francisco (again with Vizcaino), to thrust Kent into star territory. In San Francisco, starting with the ’97 season, Kent would hit behind Barry Bonds, see streams of good pitches, hone his power stroke, and begin printing his calling card: most career home runs by a player who primarily played second base, 351 of his 377 total. Not Hornsby. Not Morgan. Not Sandberg. Kent…yeah that Kent. Turns out his 1993 was the start of something big. How big couldn’t be known then. In 2000, he won the National League MVP award for which Piazza was frontrunner deep into summer. Mike caught every day and it caught up with him. Bonds put up Bonds numbers, but that was to be expected. Kent produced stratospheric statistics for a middle infielder: 33 homers, 125 RBIs, a .334 batting average. The Giants finished first. So did he. Between 1997 and 2005, Jeff earned two Silver Sluggers, was named to five All-Star teams, and received MVP votes six separate times.

You may or may not have begun to connect Kent with the Hall of Fame as his career enjoyed its highest heights, bulging with slugging statistics as it was. A lot of sluggers had impressive statistics in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some seemed less impressive as revelations came to the fore. None attached themselves to Kent. He was the second baseman with the most home runs. After he finished up in 2008, his name tended to get mentioned in the company of those who would be crowding the ballot in 2014. Greg Maddux, Frank Thomas, and Gl@v!ne figured to be locks, and they were. Mike Mussina would creep up the ranks until winning the golden 75% of the BBWAA vote in 2019. Kent went ten years without cracking 50%. Then came the committee, which took a closer examination of his calling card. If he wasn’t the ablest defender or the friendliest teammate, he didn’t have to be. No second baseman hit more home runs.

[20]This all followed the Kent-for-Baerga trade. Baerga gave us one solid veteran-leader year during his 1996-1998 stay, coinciding with the Mets’ ascent to contention. When Alfonzo was inducted into the club Hall of Fame in 2021, he invited Baerga to be an honored guest at the ceremony, indicating some genuine impact from the man who was our Carlos B before we came to know Carlos Beltran. Contemporary accounts of the rising 1997 Mets pointed to Carlos Baerga as a clubhouse catalyst [21], and he definitely chipped in some big hits as the team rose from 71-91 to 88-74.

[20]This all followed the Kent-for-Baerga trade. Baerga gave us one solid veteran-leader year during his 1996-1998 stay, coinciding with the Mets’ ascent to contention. When Alfonzo was inducted into the club Hall of Fame in 2021, he invited Baerga to be an honored guest at the ceremony, indicating some genuine impact from the man who was our Carlos B before we came to know Carlos Beltran. Contemporary accounts of the rising 1997 Mets pointed to Carlos Baerga as a clubhouse catalyst [21], and he definitely chipped in some big hits as the team rose from 71-91 to 88-74.

But with massive hindsight, it’s hard to say we won the second Jeff Kent trade, just as it’s glibly easy to say we won the first one. You trade for a future Hall of Famer before it is sensed he is a future Hall of Famer, you’re entitled to call it a win. You trade one away? Well, that’s the business of baseball. Baerga, who had been really good for Cleveland until he wasn’t, lingered long enough in the bigs to play for the 2005 Washington Nationals. Cone had enough pitches in his right arm to return to the 2003 Mets following some notable successes with Toronto (World Series ring), Kansas City (Cy Young Award), and some other New York team (whatever). Yet they’re not Hall of Famers. Maybe Cone deserved a closer look [22], but to date he hasn’t. Hell, George Foster hit 348 home runs in an era when that was a ton, and received only negligible Hall support in four elections — and he had his own comic book!

[23]Let’s leave George out of it for the moment. Let’s consider Hearn for Cone for Kent for Baerga, plus Cone coming back to finish up in orange and blue, and Hearn persevering through health issues to make all the 1986 reunions, and whatever it was Baerga taught Fonzie that shaped Edgardo into the most important non-Piazza player we had during the Bobby V years. Let’s say we won the Jeff Kent Trades over and over, even if Kent didn’t make a semblance of a case for immortality until he made it to San Francisco.

[23]Let’s leave George out of it for the moment. Let’s consider Hearn for Cone for Kent for Baerga, plus Cone coming back to finish up in orange and blue, and Hearn persevering through health issues to make all the 1986 reunions, and whatever it was Baerga taught Fonzie that shaped Edgardo into the most important non-Piazza player we had during the Bobby V years. Let’s say we won the Jeff Kent Trades over and over, even if Kent didn’t make a semblance of a case for immortality until he made it to San Francisco.

Had he stayed a Met, you imagine the bat would have found a place in that late ’90s lineup, but once we had Fonzie at second and Robin at third, did you miss Jeff Kent whatsoever? For that matter, did you miss Nolan Ryan when we were running Seaver, Matlack, and Koosman to the mound every week? Besides on principle? Transactions are nuanced. They can look bad in the moment and worse with perspective, but not totally disastrous in the scheme of things.

Thus, I am comfortable to declare that it really happened. We traded somebody at the top of his game for a veritable unknown, and the veritable unknown went on to a Hall of Fame career after the Mets got him. Also after he left the Mets. A lot more after he left the Mets than when he was with the Mets. Honestly, an accurate assessment of trading for and away Jeff Kent requires immense nuance. In a comic book universe, however, we can position the facts as we see fit to create the most crowd-pleasing storyline we can.