The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 20 June 2007 7:42 am It was a team of Cuddyers versus a team of cadavers Tuesday night. Who would your money be on?

I suppose there's no shame in losing to one of the pitchers if not the pitcher of our generation, but there is a mighty-Mississippi-wide difference between taking a few collars and tipping a few caps and meekly grounding, flying, popping and lining out 26 times — with one late K mixed in to keep the whole thing on the up and up. The Mets lost for the millionth time in their last million and three games. As has been the case for almost all of these losses, they looked pathetic, impotent and beaten from the start.

We were stymied on offense by the magnificent Johan Santana and overrun on defense by, if I'm reading the boxscore correctly, everybody who wore a Twins uniform, save perhaps for Ron Gardenhire. The four errors didn't help. The dreadful pitching by returned-to-Earth Jorge Sosa didn't help. Actually, nobody helped. Everybody hurt. This loss, much like just about every loss since June 3 when the current chain of pain began, was a total and complete Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York effort.

Go team.

Tuesday it was the Twins who were massively better than the Mets. Over the weekend it was the Yankees. Before them it was the Dodgers and the Tigers and the Phillies and the Diamondbacks. True enough that each of these units is a quality outfit. Many of them, as has been tirelessly documented, were 2006 playoff participants and every one of them owns a winning record in 2007. Oddly enough, so do we. We're still in first freaking place after not quite three of the most rancid weeks I've ever seen a Mets team compile. Gil help us once the Braves, Phillies and Marlins are no longer subject to American League opponents.

Can you believe it's not even three weeks that this has been going on? Three weeks ago at this moment I had drifted off on the couch to the blissful images provided by Jose Reyes bouncing, Armando Benitez balking and Carlos Delgado blasting. That was three weeks ago. May as well have been another lifetime. The next night Barry Zito dropped a Santana on us. Not quite as complete, but we tipped our caps and won the night after. Then in came the Diamondbacks and by the end of that series, the slide was in progress.

Well, that's not telling you anything you don't know. I wish I could pretend to have reliable sources and report the exact cure, but I don't and I can't. In lieu of certainty, any suggestions? I dunno. Turn over a buffet table? Reinstate kangaroo court? Hold extra fielding practice in the midday sun? Punish every miscue with a mandatory slice of that awful Sbarro pizza? Trade for…oh damn it, I don't want to talk about trade rumors in June. I hate trade rumors. Trade rumors are what fans of teams who are thread-hangingly in it or hopelessly out of it cling to for the balance of the summer — who we must trade for…and which Quadruple-A stat monster none of us has seen must come up…and who we must sign in the next class of free agents.

I hate that stuff. I'd rather join a fantasy league than feel compelled to think in those terms midyear. I loved last summer because I barely heard a peep of trade or minor league or December chatter. I'm sure it was there but I didn't listen to it. I tried not to indulge it anyway.

Now? For now I'm answerless. There's the occasional evening's peace when the Mets play like what we thought we could safely assume the Mets would be, but it doesn't last. The Mets haven't won a game directly following a previous win since May 29, since the Reyes-Benitez-Delgado bounce/balk/blast game. Monday night was the first game since June 2 to feature hitting, pitching and defense acting in concert. If it wasn't a can of whoopass, it was close enough, and if we could open anything approaching a can of whoopass on the Minnesota Twins for one night, you'd figure we could at least gather a collective pulse for the challenge of facing Santana the second night. But you'd have figured wrong.

The only saving grace I can find, other than Johan Santana will not be pitching Wednesday night, is we are not the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. This isn't a gratuitious shot at (youthful potential and Oriole chaos notwithstanding) the sport's worst franchise either. I fell into the Devil Rays-Diamondbacks game in Phoenix after our fleeting attempt at professionalism, and the Devil Rays have not grown one inch in their decade on the planet. Arizona fell behind 8-2 in the fifth, but Tampa Bay couldn't hold the large lead. Tony Clark hit a two-run pinch-homer in the ninth off previously unblemished closer Al Reyes to tie matters at eight in the ninth and Chris Young launched a two-run job off Reyes' 44th and final pitch in the tenth to make it Arizona 10 Tampa Bay 8, arrive home safely.

The Diamondbacks did to the fourth-place Devil Rays what we did to the Diamondbacks that first Thursday night at Chase Field when we were the team for whom no deficit was too big, no hurler too daunting, no circumstance too impossible. I was actually getting nostalgic for the 2007 Mets of April and May. I can't imagine our current crop of June bugs being any more than mere pests to a team of middling or better caliber. It's the same guys, mostly, but their hearts or their guts or their souls or their ability to play decent baseball for as many as two consecutive nights…let's just say that at this moment we're a first-place version of the Devil Rays. But just barely.

We're actually only seven games better than they are. And I wasn't planning on using them as our yardstick this season.

by Jason Fry on 19 June 2007 6:22 am Granted, it hadn't done much to repair or losses or been much of a blessing to us recently. But last night was a night to remember the simple sweetness of what baseball's like when your team isn't trying to remove your heart from your body with a rusty box cutter while you bite through your own hand. I mean, sit on the couch, admire a good pitching performance, take in a little drama and then be able to relax? I could grow to like this sport.

Given our recent awfulness and the late rally that turned this one into a laugher, the Twins were kind of beside the point. Not that I know them anyway — I kept peering at the screen and wondering if that was Mauer or Morneau. Minnesota Twins … hmmm. It's the place where Jerry Koosman, Wally Backman and Rick Reed got exiled. The hats say TC, which baffled me as a child. There's a weird stadium and a baggie. Kirby Puckett played there. They beat the Braves in the best World Series I've ever seen. They never beat the Yankees in the playoffs. Bud Selig tried to contract them. Everybody forgets they're an original American League franchise. They're run cheaply and make up for it with smart GM-ing. And that's a wrap. (I know that sounds a lot like my mental checklist when we played the Tigers. What can I say? I'm not going to take AL Central for $100, Alex.)

I'm giving the Twins short shrift not to be insulting, but because tonight was so much more about us, about looking for positives and finding some and then finding a whole lot more and then finally exhaling because there were enough positives that you could select them randomly instead of counting them up. John Maine, last seen handing out souvenir dingers to the entire Dodgers lineup? He was terrific. Carlos Delgado? Hit a home run and came within a Jason Kubel half-tumble of driving in two more. Carlos Beltran? Had good at-bats and actually got rewarded for them with a rifle double up the gap. David Wright? Three hits, nearly hit a home run, continued his sharp play at third. Jose Reyes? Scampered about gleefully. Heck, even Ricky Ledee went deep.

It was a game from the template of April or May. It was baseball like it oughta be. And it was wonderful.

Update: If you followed the link from Deadspin, welcome. To be clear, we doubt there's any truth to the blog post whispering about some kind of racial divide in the Mets clubhouse. Or to Julio Franco stirring it up. By the way, our sources tell us Roger Clemens subsists entirely on a diet of live kittens. Pass it on!

by Greg Prince on 18 June 2007 7:45 pm

If you wear it, they will come…or something like that. Our own Mets Guy in Michigan Iowa, Dave Murray, bears the numbers of four New York National League legends as he looks for a pickup game against Joe Jackson and the rest of the 1919 Black Sox on a recent visit to Dyersville, site of the field from Field of Dreams.

Is this Heaven? No, but we assume it was named for Duffy Dyer, so it’s close enough.

by Jason Fry on 18 June 2007 4:53 am Like all good-hearted people, I hate the Yankees.

When you break down that statement a bit, though, things get more complicated. The only members of the current roster whom I actually loathe are Satan and Miguel Cairo, and Miguel Cairo isn't worth more than passing bile. What I really hate is the franchise as a collective entity. And most of what I hate about it is the front-running, gimme-gimme fans with their sense of entitlement and their love of rooting for the overdog.

But only most of it. I also hate their cheap propagandists, Michael Kay and John Sterling and Paul O'Neill and Suzyn Waldman. A list to which we may as well add Joe Morgan and Jon Miller. Who, really, deserve our derision even more than the pitiable Lord Haw-Haws of YES and WCBS. Because Morgan and Miller are supposed to be neutral observers. They're supposed to be pros.

Watching tonight's game, you'd never guess who was in first place and who'd only just closed within double digits. You'd have no idea which team played an all-or-nothing game to go to the World Series and which was sent packing in the first round of the playoffs. If it wasn't Jeter's radiance it was Clemens' heroic journey back to the bank or Ron Guidry's ancient glory days. Those guys in the other dugout? Um, there was Jose Reyes, discussed mostly as Jeter's foil. And a couple of mentions of David Wright. El Duque got a retrospective of sorts — of his days as a Yankee.

Seriously, let's review some of the things I saw before I got so disgusted that I retreated to Howie and Tom:

* An “acrobatic play” by Derek Jeter that sure looked like a routine assist on a groundout to me.

* Did you know Jeter has cute little nicknames for his teammates? Like he calls Robinson Cano Canoe? That's why they call him Captain Intangibles. Championship stuff there.

* Later, Morgan went out of his way to praise Jeter for a tag play. The way he put his glove in front of the baserunner's hand was gritty and gutty and showed all the kids out there the way the game's supposed to be played, I guess. Only it was Canoe who did that. I mean Cano.

* A lame softball interview with Satan by Peter Gammons, who's so much better than this. Miller almost got in a mild dig at Clemens, noting that he was in fact with the team despite not pitching tonight, but then the Yankee chip in his head started beeping and he made Clemens' attendance sound like a tour of duty in the Peace Corps. And how did Clemens do against the Mets Friday night? Apparently he was beaten by Jose Reyes. No mention of who'd opposed him and thrown a shutout. None whatsoever.

* A while later, Morgan did recall (in chatting with Willie Randolph, who looked like he'd just been force-fed an entire lemon tree) that there'd been a Met pitcher in that game who'd done OK in the shadow of the Great God Clemens. And so he asked Willie about Odalis Perez. (I know they talked about Oliver a couple of innings later. Too little too late. And then Morgan came up with some tortured musing about the Yankees would have won if they hadn't had baserunners on at unlucky times. Or something. I got dizzy trying to follow it.)

Look, 8-2 is a beating. Chien-Ming Wang was masterful. A-Rod hit a ball to Montauk. Our various problems — crappy hitting, bad relief, dopey plays, whatever the hell's wrong with Beltran — weren't exactly erased by one good game by Odalis Oliver. But the bowing and scraping in the direction of Monument Park started long before the game cratered.

I've given up on respect in the tabloids and on talk radio — the circus is always going to be run by hucksters and suck in its share of rubes. But is it too much to ask that the self-appointed world-wide leader in sports do a little better than three hours of mash notes to one side of the room? The only saving grace of last night's loss was if you watched it on ESPN, you barely knew the Mets were there in the first place.

by Greg Prince on 17 June 2007 8:22 am The New York Mets play the New York Yankees for the sixtieth time in regular-season competition tonight. That is if the weather cooperates. Three times the weather hasn't cooperated: June 11, 2000; June 21, 2003; and June 25, 2004.

I remember those rainouts. I remember almost everything about every Subway Series. A few details about a few losses have probably fallen between the cracks — there have been 34 losses spread over 11 seasons, so it is probably best to let a few slip away — but mostly it's all fresh in the mind's eye, no part more fresh than the segment that came first.

Imagine something for the better part of 35 seasons and once it finally happens it's pretty thrilling. That was what every New York baseball fan likely did at least once between 1962 and 1996. Mets versus Yankees? It may not have been a universal concern, but there were enough Grapefruit League and Mayor's Trophy games to make one wonder what if they actually played each other for real? And so, by aegis of the commissioner's office, it happened.

You may have forgotten a lot about 1997, but you haven't forgotten June 16. Even if you don't remember the date, you remember Mlicki. We all remember Mlicki. We're all still lining up, if we're any kind of decent people, to buy Dave Mlicki a drink or a car or some token of affection for putting the Mets up 1-0 in all-time competition versus the Yankees ten years ago yesterday. Dave Mlicki was one of the most frustrating right arms the Mets ever had. He should have won 15 games every year. He never won more than nine. The year he shut out the Yankees 6-0 — we beat the Yankees! — his record was 8-12. While he was on the job, Dave Mlicki could be irritating in his determination to not get the third out, not throw the third strike when he needed it.

Do you remember that? No, you remember 6-0 on June 16, 1997. You remember barely controlling your excitement and/or your angst if in fact you bothered to try. From the first pitch of that first game, Andy Pettitte to Lance Johnson, I needed weighted boots to keep my feet on the ground. Strip aside playoff games from '88 and key pennant race games from the years surrounding those and this was the biggest game since Game Seven against the Red Sox. In the Self-Esteem Division of the Emotional Well-Being League, it was the biggest game ever.

We led from the first inning on. We never trailed. We won. What if the Mets played the Yankees in a game that counted? The Mets would win 6-0. We had our answer.

So why did the question have to be repeated 58 going on 59 more times?

If we had stopped with Mlicki and 6-0, that would have satisfied everybody. We would have had our win for all time and they…well, what do I care about them? Part of the social contract of following one team in a two-team market is the implicit understanding that you don't have to bother with the other team. Prior to June 16, 1997, I didn't have to think about the New York Yankees very often if I didn't want to. I didn't want to. If I did, they were right there for the following when I started with baseball. I went with the Mets and that was that. The Yankees had their downs and ups and their cycles (some lasting distressingly longer than others) but they existed in somebody else's vacuum for my purposes.

That changed as of June 16, 1997. They weren't just a psychic enemy by dint of obnoxious co-workers and classmates, they were opponents. They were on the schedule. You could ignore the Yankees to the best of your ability — preblog media making that a tough enough task — but now you had to stare them in the face three, then six times a year every year whether you wanted to or not.

It's easy to bash Interleague. It's easy to point to any game that involves the Devil Rays or Royals taking on a National League team, or the Pirates or Rockies going against an American League team and snottily dismiss it with “well, there's a rivalry everybody wants to see.” To which I say, what do you want from these clubs? They're part of a larger structure, they have to play somebody. I imagine there was a moment in baseball history when the Pirates playing the White Sox would have caused quite a stir, maybe around 1960 or 1972. I tuned in briefly to their game last night and saw loads of empty seats at PNC Park, no different than it would be if the Pirates played just about anybody these days.

So Interleague isn't a panacea through no fault of its 30 participants, some of whom undeniably suck regardless of matchup. But it does rock New York and a few other intracity locales as has been well documented by the Attendance line at the bottom of boxscores since 1997. People show up. Hardly anybody claims to like it anymore, but I'm waiting for the first Subway Series game in which you can walk up to the ticket window an hour before first pitch and purchase four on the aisle in either Queens or the Bronx. I made it my business to go the first one at Shea in 1998 for the sake of history. I relished the chance to go the next couple of years because, duh, it was the Mets playing the Yankees. Since 2001, I simply hate the idea that a Yankees fan's ass might be taking up my rightful space.

Hmmm…I wonder how much more they could charge for admission if they marketed it as “Don't Let Those Bastards Sit In Your Seats.”

It's not like we don't get our money's worth out of the Subway Series. Pound for pound, Mets-Yankees games have to be the most breathtaking of any games in the Majors in just about any year. Tell me each side doesn't play its heart out even after they spew quote after quote about how it's either just another game or, worse, a pain in their excessively compensated ass. Think how many games you can instantly identify by name since 1997. The Mlicki Game. The Matt Franco Game. The Shawn Estes Game. The Mister Koo Game. Think how many obscurities spring to life through the prism of the Subway Series and how instantly incandescent they become. Shane Spencer…Ty Wigginton…Richard Hidalgo…and that was just one weekend in 2004.

Come to think of it, save for Piazza being Piazza on multiple occasions and Wright and Floyd using Yankee Stadium's upper deck for target practice on June 25, 2005, does it strike you odd that so many of our triumphs against baseball's best-funded corporate entity have been won on the wings and prayers of relative obscurities? Even obscure for the Mets? Would you be able to differentiate Dave Mlicki from Robert Person or Mark Clark if not for the Subway Series? Would Steve Bieser's Q rating be anywhere near as high as it is if not for the balk he teased out of David Cone on June 18, 1997, two days after Mlicki had his passport to Amazin' immortality stamped? Would Tsuyoshi Shinjo's orange wristbands burn as brightly in memory if he hadn't given over a quad to beat out a play at first, thus setting up Mr. Mike's midnight roughshod ride over Carlos Almanzar on June 17, 2001?

Perhaps it's a function of not having that many stars, at least not until fairly recently. Who does the damage for the Yankees? Not Carlos Almanzar or Enrique Wilson or Tanyon Sturtze, cherished goats from our perspective. It's Jeter and A-Rod and Jeter and Posada and Jeter and Giambi and Jeter and, earlier, Williams and Jeter and Martinez and Jeter and O'Neill and Jeter.

It's always fucking Jeter, isn't it? He kicks our brains in and then he's selling us a Ford Explorer. Can somebody please screen these ads ahead of time?

We play the Yankees just about as much as we play any N.L. Central or Western opponent. Mets-Astros games may have their own particular flavor but there's no denying a unique culture has sprung up between the Mets and Yankees. There are five essential types that can describe just about every Subway Series game.

• The joyous bizarrofest won by the Mets, definitely the class of the genre of which The Matt Franco Game of July 10, 1999 is the archetype and patron saint.

• The inane choke lost by the Mets, such as the end of the world brought to us by Billy Wagner on May 20, 2006 but honed to imperfection by Armando Benitez on June 14, 2002 and Braden Looper on June 26, 2005.

• The scintillating pitching & defense duel won by the Mets, last spotted Friday night, previously spun May 18, 2007 via Oliver Perez and Endy Chavez.

• The slopfest lost by the Mets — you know, like Saturday.

• The dull Yankee win, representing probably a bulging plurality of the 34 Met losses since June 17, 1997, particularly on Sunday nights.

Ah yes, ESPN games are a notable subgenre of the Subway Series. They used to present the occasional uplifting breakthrough (Luis Lopez sac-flying home Carlos Baerga while Brian McRae dawdled around first on June 28, 1998, thus saving us from completely losing Shea face; Al Leiter stopping the coach-firing, losing streak madness of June 6, 1999 and sparking up a 40-15 run for glory), but ever since the first Subway Series rainout — Ventura flopping around on the tarp with a fake Mike mustache which was funny until it wrought that horrendous shame-of-the-franchise day-night doubleheader of July 8, 2000 — Sunday nights have increasingly morphed into episodes of embarrassment. We actually won the first four ESPN games we played against the Yankees. Yet after Sunday night June 16, 2002 — Mo Vaughn hammering David Wells at Shea — we are 1-7 in the Simpsons/Sopranos slot, up through and including the unawaited debut of Tyler Clippard on May 20, 2007. Lifetime with Joe Moron and Jon Imbecile bungling the action, we're 6-8. You can keep prime time.

Let's say you have a game like Saturday afternoon's. I'd rather not, but we did. Even as it dragged on until Carlos Beltran courteously ended it with one swing, we were guaranteed the agony of 24+ hours without a chance for revenge. That's the worst part of the Subway Series, save for the 34 losses. The waiting is indeed the hardest part. I don't do or think anything special for games against the Phillies or the Nationals or even the Braves unless circumstances dictate otherwise. For 15 regular National League and 13 intermittent American League opponents, it's generally enough to pay a little attention beforehand and turn on the TV once the clock strikes 7.

Not with these games against the Yankees. I try everything including trying nothing. When the Subway Series was still novel, even when it was getting old, I allowed myself to get sucked up into the hype Subway Series Fridays brought. I bought all the papers, I stayed glued to the FAN, I watched the idiots-screaming-into-the-camera features on the news. This past Friday, I decided to go unspoiled. I read nothing. I heard nothing. I watched nothing. I didn't even wear a Mets t-shirt. Because my strategic disengagement worked (that and Ollie), I tried it again Saturday. The results were mixed, then abysmal. Once it was 10-5, I pulled out a trick I use only in dire circumstances. I dropped all television and radio contact, which is different from simply turning off your sets right there. We needed to pick up a few things at Stop & Shop, so pick up we did. Pick up and leave Channel 11. No earbuds, bud. No concern for what was going on in the late innings. None evinced, anyway.

We arrived home for the top of the ninth, groceries in, garbage waiting to be taken out. I'll just sit and watch this disaster, now 11-6, go final and then hit the dumpster, figuring I'll see the Mets there in about two minutes. Then Delgado gets a hit. And Lo Duca. An out but then Castro gets a hit. Gotay doesn't, but Gomez battles Rivera so hard that it must elicit a reflexive smile from Art Howe in Cincinnati with the Rangers. It's 11-7. Stephanie hands me a rainbow roll from the Stop & Shop seafood department. I chew on it as if it's the most important thing in the room. I can't invest outward interest in what's on the TV. I walked away from this game and now this game has come crawling back to me. If I embrace it, it will only turn on me in anger.

Reyes's turn to not give up the ship. And he doesn't. It's 11 to 8. I'm out of rainbow roll. I just sit and stare and Beltran. If I make too much out of the bases being loaded and our technically best player coming up, there will be nothing to come of it.

I act like this at Shea once in a while. And I certainly twist my thoughts into pretzels dozens of times a night so as to bring good luck or not bring bad luck to the Mets. But this kind of thinking, this kind of anxiety, this brand of intense, insane, insipid ohmigodibetternotscrewthisupforus contortionism doesn't happen when the Mets play 15 regular National League and 13 intermittent American League opponents.

I don't know if I should credit or blame the Subway Series for this strain of behavior. Anything that makes you feel baseball this much is probably a worthwhile if utterly unhealthy endeavor. I love beating the Yankees. I hate losing to the Yankees. Fifty-nine times since June 16, 1997, I've experienced the sweet and the bitter ends of this particular rainbow roll repeatedly. Both are tastes you never quite get out of your mouth.

But on the eve of my sixtieth bite, I wouldn't put up much of a fuss if they decided not to serve us any more after this. Really, I was sated after the first helping ten years ago yesterday.

by Greg Prince on 16 June 2007 10:41 pm Scratching out two singles makes him just a bit less Wilson Delgado and a bit more Carlos Delgado for the day (though that fifth-inning cutoff clank which allowed Cano an extra base and eventually an extra run was worthy of Marvelous Marv Delgadoberry). Alas, if one can take a slight breather from mulling What's Wrong With Carlos Delgado?, one must now join in progress the vigil as regards What's Wrong With Carlos Beltran?

On an endless afternoon when everybody hit somebody sometime, Beltran didn't hit at all, didn't get on base, didn't show any signs that he is Carlos Beltran, millionaire, who owns a mansion and a yacht. 0 for 6. Oh for six. Six times up, no times on. There isn't a way to term it or type it that makes it any less unappetizing.

What's wrong here? The knee? Getting his timing after taking time to heal the knee? Retraining his eye? Not that the game wasn't lost many times in many ways by many Mets between innings one and eight, but how on earth could a man who is so incredibly skilled at taking pitches (ahem) swing at the very first one thrown toward him by Mariano Rivera after the Greatest Blah Blah Blah Ever is obviously waaaaay the fuck off his stride? Rivera threw 32 pitches to 7 batters and allowed 5 hits in the ninth. He throws 1 pitch to Beltran and Beltran swings at it and Rivera slithers away essentially unmolested.

I can't imagine how one differentiates, from the batter's box, in nanoseconds, between a good pitch to swing at and a good pitch to take. But after a closer in a non-save situation — which always screws them up — has struggled to get three simple outs against one very simple team and has afforded said team a gaping if undeserved shot at redemption, I can differentiate between a good opportunity to take and a good opportunity to swing and pop up and call it a night.

Delgado wallowing in a slump I can live with somehow. I've seen it before and we persevered together, he and us. But Beltran, lordy, he's just too important to this team. When he sucks, we suck. I've given the matter a great deal of study and have reached the considered conclusion that he just can't be doing that.

by Greg Prince on 16 June 2007 8:29 am They pull a knife, you pull a gun.

He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue.

They start Clemens, you start Perez.

That's the Met way.

In five games this season against the despised Braves and the detested Yankees — the intersection of haunting nightmares and the uncontrollable shakes — Ollie's ERA is 1.26. He's 5-0 against our most bitter rivals. If you need someone to take out a ghost or two, Ollie is obviously your man. Throw in his respectable work from seventh games of championship series and it appears this fellow might very well be a keeper.

Oliver Perez is clearly the most interesting starter on the active roster. It's no longer a question of not knowing what you're going to get. You know you're likely to get quality. You're just not sure how you're going to get it. Friday night I found it fascinating that both Billy Wagner and Jorge Posada, who presumably did not compare talking points, both called him effectively wild. That's a lot different from “oh dear, he's gone three and oh again.”

Of course he had help. It's about time somebody on the Mets helped somebody else on the Mets, each of them riding around the last road trip aimlessly, 25 Mets in 25 directionless cabs. Carlos Gomez certainly threaded the needle in left, the needle being morons with outstretched hands. There was a little pinch of Endy on display, though certainly not as polished. He does have that “Skates” quality in his stride; two or three times I was sure he pulled something he needed for running.

Back in the era of good feeling, I was ready to stamp Carlos the Third's ticket back to N'Awlins, having watched his average spiral and his savvy fail to sprout. Seasoning is why we relocated our triple-A operations to the home of Cajun cooking, right? But the Mets are in no position to send back a player, no matter how undercooked, who can create a run and save a couple more. And this unexpected accumulation of Major League service time might not be so bad. His career trajectory to date is a bit reminiscent of his big brother Jose Reyes. Jose was up too soon, it was said, and could have used a little more good Tideing. But between injuries and pervasive team lousiness in 2003, Reyes was never shuttled off to Virginia and, growing pains notwithstanding, I think it was to his benefit. We could see it with Gomez. Let the trial be by fire. But somebody make sure the kid stays on his feet.

Had to love the bunting on Clemens and his fatigued groin (boo frigging hoo). It's just smart baseball. You've got the tools, use them. Ron Darling noted fielding bunts is one of those disciplines drilled into you during Spring Training and hey, guess what, Clemens didn't bother with Spring Training. But he and his agent did stay at a Holiday Inn Express last month.

Six-and-a-third innings of two-run ball, as representative an outing as it was for (grumble, grumble) a Hall of Fame pitcher, rates a million bucks? Now that's smart baseball! Why bother with the fundamentals when all you have to do is show up in June, stick around the premises only as long as you feel necessary and not be expected to complete seven?

Apropos of nothing except my enjoyment of The Ballclub's recurring and regularly compelling Lost Classics feature, I found myself recalling the last two times the Mets faced the, oy, Rocket. He was an Astro and he was good.

May 16, 2004: 7 IP, 0 ER, 2 H, 1 BB, 10 SO

April 13, 2005: 7 IP, 0 ER, 2 H, 1 BB, 9 SO

Clemens as an Astro didn't pack quite the putrid punch as did and does Clemens the Yankee only because Strychnine presumably doesn't taste as bad as Drano. Don't get me wrong. I was steadfast in my desire to watch the mound open up and swallow him and his rapidly fatiguing groin with one enormous suck during his Houston hiatus, but I was willing, in the abstract, to grudgingly admire his pitching output if not the outputter himself. Mike Piazza's two-out, ninth-inning, game-tying home run off Octavio Dotel to cost Clemens a victory at Minute Maid in '04 (Jason Phillips getting his wallop on to win it in the 13th) and Kaz Ishii — remember him? — matching Clemens pitch for pitch the following April at Shea (Reyes singling home Victor Diaz in the eleventh for walkoff closure) positions each of these as Lost Classics candidates, but what seals their respective nominations is the fact that Roger Clemens started, Roger Clemens excelled and Roger Clemens was no-decisioned as the result of Met lightning striking.

I'd give Clemens plenty of credit for striking out eight Mets during his lucrative if abbreviated Friday night stay, but those of us who remained awake through the Los Angeles lossquake know that isn't terribly impressive (4 through 8 in the order: 0 for 19 with a walk), especially since three of those K's were Delgado, Delgado and Delgado, with more Delgado striking out a fourth time after Clemens left. CD really is in Montañez territory right now. Here's what I mean:

Wille Montañez 1978

First Met Year

Age: 30

Games: 159

HR: 17

RBI: 96

BA: .256

OPS: .712

Willie Montañez 1979

Second Met Year

Age: 31

Games: 109 (traded in August)

HR: 5

RBI: 47

BA: .234

OPS: .594

Or try this:

Bernard Gilkey 1996

First Met Year

Age: 29

Games: 153

HR: 30

RBI: 117

BA: .317

OPS: .955

Bernard Gilkey 1997

Second Met Year

Age: 30

Games: 145

HR: 18

RBI: 78

BA: .249

OPS: .755

As for the present:

Carlos Delgado 2006

First Met Year

Age: 33/34

Games: 144

HR: 38

RBI: 114

BA: .265

OPS: .909

Carlos Delgado 2007

Second Met Year

Age: 34/35

Games: 62

HR: 10

RBI: 39

BA: .221

OPS: .687

Delgado owns a deeper portfolio of accomplishment than Montañez or Gilkey, but he's also older as he teeters. His predecessors in disturbing falloff surprised the Mets with their acquisition-season productivity; Gilkey tied the team ribby record (in his walk year — also very smart) and Montañez's 96 runs batted in were actually third-most in Mets history at the time…and driving in nearly one hundred 1978 Mets was a feat of mind-boggling proportions considering how doubtful it is that one hundred Mets actually reached base in 1978.

We know Carlos was extremely streaky in 2006. His April, however, set the tone for the new, improved lineup and when he faded for extended intervals, it barely mattered as everybody else was scorching. It felt like Delgado got back half his power numbers in about three weeks in August (a month when he swatted eight homers and drove in 26 runs), thereby piecing together one of the better slugging seasons we've ever seen in these parts. That batting average was eerily low, but he was getting on base and driving the ball enough to write off that .265. Now .265 is sadly aspirational.

Don't mean to take the edge off a sweet victory, considering the circumstances, the opponent and the opposing and losing pitcher, but I'll feel a lot better when Delgado is cleaning up something besides the dregs of what was a fabulous career.

by Jason Fry on 16 June 2007 3:26 am When they brought the Antichrist back, it wasn't a sure thing we'd face him. Then it looked like their rotation wasn't aligned for another meeting. And that was fine with me. It's an old hatred by now, a grudge that involves vanished players and distant times. I can reach back and bring the causes back to life, but a lot of the hatred has become ritualistic, received wisdom — Greeks and Turks, Shiites and Sunnis, Hatfields and McCoys. Long ago something happened, and now we hate.

It didn't help that yesterday was one of those rarest of days in a baseball season — a day your baseball team isn't playing and you're glad. It seems crazy — in January you'd traverse the desert to see three scoreless innings between the Angels and the Rangers — but it does happen, and Thursday was proof. Did any of us want to see the Mets take the field after their humiliation by the Dodgers and apparently mute acceptance of same? They needed a day off. We needed a day off. But with Clemens and the Yankees on deck, that day off was inevitably spent bemoaning everything that had happened and fretting about everything that might happen.

Tonight was our final night on LBI, and Emily and I hijacked the TV and provided a running lesson in Met history and hatreds for our housemates. Two of our friends have an eight-year-old son, and we were off and running when he asked, “Why do you hate him so much?” I left the explanation to Emily and she provided, delivering a capsule biography that included Piazza, the bat shard, headhunting and hiding behind the DH. (I might have removed myself from consideration by telling Joshua, “You know how we say we don't want bad things to happen to any person? Well, that doesn't apply here. The Yankee pitcher is a very, very bad man, and if an asteroid crushes him, Mommy and Daddy will be happy.” Oh, and I also tried to convince the eight-year-old that you could see the stump of his tail. And if I were in a court of law, I would have to admit to saying he colored his hair with the blood of innocent children. What?)

The game itself was light on historical digressions, because they never would have ended. How could you sum up the rancid brew of emotions that churned in our guts when Oliver lost the plate and finally threw a strike that wound up with Carlos Gomez feeling for the left-field fence on a ball that was obviously going to be a home run? I mean, where to start? Todd Zeile hitting a ball to pretty much the same spot, only in that game the smartest Yankee fan on earth is in the seat and doesn't touch the ball, and Timo Fucking Perez doesn't fucking run and Derek Jeter does what Derek Jeter does and Armando Fucking Benitez walks Paul O'Neill and we're doomed, doomed, doomed. And of course it's hit by Miguel Cairo, one of the more useless Mets of recent memory who regards his time at Shea like we regard three hours spent in the DMV. And Gomez is a baby whose outfield play has been a little shaky considering all his talent and there are 55,000 baying on the biggest regular-season baseball stage of all. Telling the backstory of that one would scare any eight-year-old away from the game — best to avoid any sport where one home run barely sneaking over a fence can unleash such a geyser of bile and pain.

Only it isn't a home run. Two Yankee fans whiff on the ball. Gomez makes a great catch. Hideki Matsui is halfway to third for no apparent reason. Inning-ending double play and Oliver has escaped the hangman.

And while our offense was still pretty slumbery (the baseball newcomers were introduced to the concept of the golden sombrero courtesy of poor Delgado), Reyes' satellite-killer and Gomez's wheels were enough. Clemens disappeared (no doubt to turn into sulfurous vapor in the shower), Joe Smith got A-Rod, Captain Intangibles' double didn't kill us and we were home free. I'm not sure how exactly 2-9 feels like a ticket to the Promised Land, but it does.

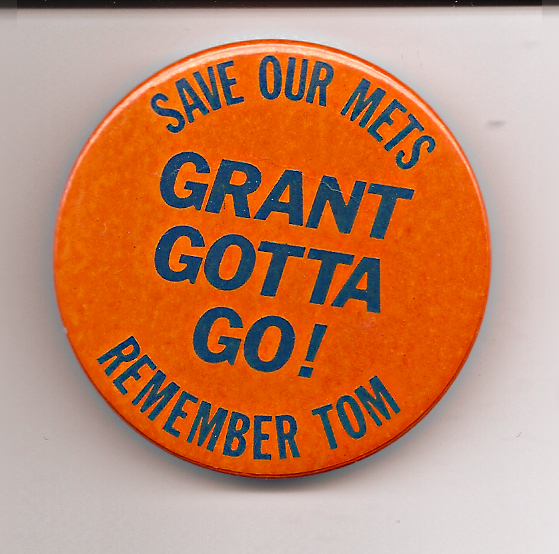

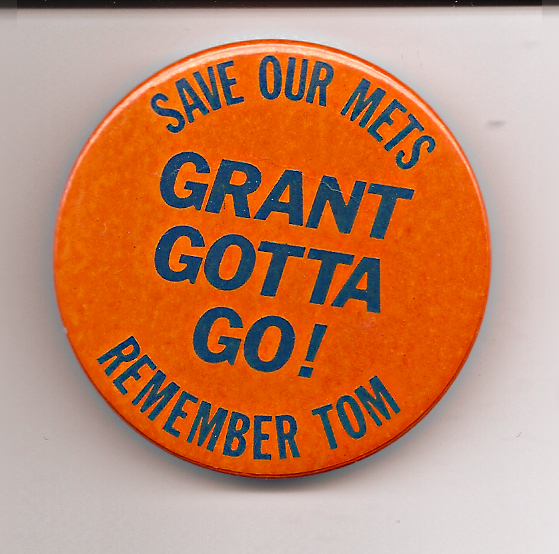

by Greg Prince on 15 June 2007 12:39 pm

Grant would be gone not all that long after June 15, 1977. And Tom would be remembered always. Saving our Mets, however, would take a while.

by Greg Prince on 15 June 2007 12:35 pm If you’re still trying to make sense out of a senseless act thirty years after the fact, then it’s Flashback Friday at Faith and Fear in Flushing.

The Mets seem to be mired in utter disarray as we speak, losers of five in a row, nine of their last ten, all four of their most recent series, each against a quality contender. They couldn’t be playing any worse. And they couldn’t be playing anybody hotter than the Yankees, three games this weekend, at Yankee Stadium.

It sounds like hell. Yet I can handle it standing on my head.

I can handle a whole host of Met hell because I’ve lived through the ultimate Mets detonator. I lived through the blowing up and immolation of the New York Mets. I lived through June 15, 1977. I was in the house when the house burned down.

I stuck around and waited for contractors to show up and start rebuilding. Not everybody did. Many fled to higher ground. Those who would define their interest in a baseball team as some kind of leisure activity related they saw fit to wash their hands of the whole mess. Why would I want to devote myself to a pastime that would make me miserable? these souls asked. They got out of baseball, certainly out of the Mets. Those who stayed with baseball and not the Mets? They will have their own Hell to deal with eventually.

Oh them of little faith and virtually no character. Silly ex-fans. Mets are for life.

Thus here I am, exactly thirty years later, alive and willing to recall the grisly particulars. So do me a favor and try not to use phrases like “I’m out on the ledge” near me to illustrate your displeasure with something as pedestrian as a five-game losing streak or an unfavorable upcoming schedule. Losing five is nothing. Losing 41 was everything.

Thing is we knew this was coming. This was in the air for a long time. In the very last edition of The Long Island Press, on March 25, 1977, Jack Lang reported it was inexorably en route:

Contrary to their denials, the Mets have promised Tom Seaver they will trade him if they can work out an equitable deal, The Press learned today.

The Press died the next day. But the talk of a deal lived on. Lang’s exclusive was the Mets would send Seaver to the Dodgers. That didn’t happen. But it was out there. The idea that our best player ever — then as now — could be swapped mainly out of management pique did not materialize without notice.

If you can ever be prepared for your one and only baseball hero to be sent somewhere else, you could have seen this coming. The ’70s in general and free agency in particular had stripped us of our native innocence. We were a cynical lot, we adolescents of 1977. Never mind Vietnam and Watergate (though those didn’t help). Sports had become a big, nasty business on our watch. If you were barely old enough to remember 1969, you were plenty old enough to have witnessed intense labor strife in and around the seasons that followed: strikes threatened, games cancelled, dynasties dismantled, contracts voided, options played out, clauses no longer reserved, checkbooks brandished, superstars dispatched over money, uniforms exchanged with alarming suddenness.

The Oakland A’s were no more, not really, by 1977. It wasn’t that I was an A’s fan. I wasn’t. But this was the dynasty of our age. This was the defending world champion we took to seven games in 1973 and felt little shame over losing to because they were the finest conglomeration of pitching, hitting, running, fielding and moxie we’d ever see operate over an extended period. But the A’s, the Swingin’ A’s who grew mustaches and challenged penurious authority, scattered to the four corners of the baseball map by ’77. Catfish Hunter got out on a technicality. Reggie Jackson wouldn’t sign so he was sent to Baltimore. Vida Blue, Joe Rudi and Rollie Fingers were sold to deep pockets, albeit temporarily when the commissioner ordered Charlie Finley to cut it out. Didn’t matter. Free agency took care of just about every Athletic still in Oakland after 1976.

If the perennial champion A’s could go every which way but on, what was the likelihood that a perpetually middling 83-79 type outfit like the Mets would be immune forever? Money and player freedom and the possibility of more money were three elements that eluded the understanding of Mets management by 1977. It was their misfortune to employ the greatest pitcher of his era, one who could command compensation every bit as handsome as he appeared on all those Mets yearbook covers.

Tom Seaver wanted the Mets to spend more money. Some on him. Some on his team. The Mets were going to do no such thing. They didn’t care for the idea of this ingrate not appreciating that they had lowballed him before free agency took hold. They didn’t think much of Tom Seaver’s 182 wins between 1967 and 1976, his three Cy Youngs, his strikeout and ERA titles, his role in leading one miracle team to a world championship and another to the cusp of a second.

At least that’s how it seemed from here. I was probably more accepting of the idea of Tom Seaver being traded in the days leading up to June 15, 1977 than I am now. It makes no sense now. It made…well, it didn’t make any sense then either, but you understood it. No, actually you didn’t understand it, but you got it. At the very least you saw it coming.

It was everywhere. It was, sadly, all that was keeping anybody’s attention on the Mets in the spring of ’77. It is perhaps forgotten that prior to trading Tom Seaver to Cincinnati and similarly embroiled Dave Kingman to San Diego and, for weird measure, Mike Phillips to St. Louis on June 15, the Mets were not exactly Camelot.

1977, based on April and May, was already the first godawful year I experienced as a Mets fan. They lost 91 games in ’74, but there were injuries (the Mets were always injured in the ’70s) and residual goodwill from ’73 and, quite frankly, I kind of zoned out that summer. 1977 was way worse. Last place was achieved May 4 and maintained steadily thereafter. Make no mistake: We would finish last without Seaver and Kingman and Phillips but we would have likely finished last with them.

Would have been nice if we could have found out.

There was no goodwill to be had that grim spring, no equity allowing anybody the moral standing to tell anybody else they gotta believe. Since 1974 we had watched Tug McGraw, then Cleon Jones, then Rusty Staub marched beyond our borders. We saw Yogi Berra take the fall in ’75 despite putting his team and his legend over the top two years earlier. Against that backdrop, what chance did Cobra Joe Frazier have?

The manager who eventually succeeded Berra was offed before his second May in the job was over, removed from office after a 15-30 start despite bringing home a pretty decent 86-76 finish the year before. It was inevitable with Frazier, and not just because he had no relevant Major League experience and not just because by comparison Art Howe really did light up a room. Nobody’s head was safe by 1977. It was shocking when Yogi was axed because he was Yogi. It was more shocking that Frazier was ever hired. There wasn’t anything surprising about his no longer managing the Mets.

Under player-manager Joe Torre (sure, why not?), the Mets briefly righted their ship, winning seven of eight into early June. That made the Mets 22-31. Alas, they were still the ’77 Mets. Swift Lenny Randle punched out Frank Lucchesi in Texas (is it any wonder we were cynical?) and wound up our third baseman. He was having a good season. And Seaver raced to his usual sublime start, racking up seven wins in his first ten decisions…his last ten decisions of local consequence, it would turn out. I don’t remember anybody else on that roster excelling.

Unraveling in the shadows of Seaver’s staredown with M. Donald Grant and Grant mouthpiece Dick Young was the Met tenure of Dave Kingman. Kingman was not Seaver. Seaver was homegrown. Kingman was purchased from San Francisco when Horace Stoneham was broke and drunk. Seaver was as well-rounded a pitcher as one could imagine. Kingman was a one-trick pony. But, oh, that trick. Whereas Seaver’s craft became what the Mets would be known for, Kingman’s single skill — the ability to occasionally launch majestic, awesome, cloudburst home runs — was an anomaly. But what a delicious anomaly on a team forever starved for power or offense of any kind. Yeah, Kingman struck out when he wasn’t homering (he left town at .209) and didn’t exactly take extra fielding practice and maybe never finished in the top percentile of his charm school class, but he was Dave Kingman. In the schoolyards of 1977 New York, Dave Kingman equaled slugger. You swing for the fences? Who do you think you are…Dave Kingman?

The Mets couldn’t afford to lose anybody who was identified with anything positive, but now zero hour was at hand. SkyKing was relatively small potatoes, no matter how tall he stood. Seaver was The Franchise, the best nickname ever assigned any Met, maybe anybody. Tom Terrific wasn’t bad either. His mind was supple, his motion was exquisite. Just by going to the mound every five days he taught a generation to pitch.

But who needed to make every effort to hold on to that? Not the Mets of M. Donald Grant and Dick Young. They were content to chase Seaver far from New York and, if the dust pulled Kingman along, that’s fine. We’re the New York Mets. We won two pennants when nobody thought we could. We had a good record in August and September last year. Who needs an All-Star slugger and a Cy Young winner?

This is the publicly articulated front-office thinking we as 14-year-old-or-thereabout Mets fans were up against as the clock neared midnight on June 15, 1977 and as I woke up for school the next morning to collect the bloody details of the instantly dubbed Wednesday Night Massacre from the radio. It may has well have been an assassination bulletin. M. Donald Grant murdered our team.

A friend and contemporary suggested to me the other day that it was the end of our childhoods. Maybe. I guess. Childhood was no age of innocence if you were paying attention to the front or back pages back then. Like I said, the realpolitik of baseball — undeniably business every bit as much as game for the previous half-decade — was in evidence everywhere. Norman Rockwell was clearly done for.

But Tom Seaver not a Met? Adults took that one pretty hard. Roger Angell: Tom Seaver is gone — no longer a Met, no longer a sunlit prominence in this flattened city of New York. Indeed, what was the point of having the Mets if you weren’t going to have Tom Seaver be one of them? Seaver was angry with Grant and pretty satisfied to be joining the two-time titleholding Reds (I just assumed his presence would mean a resumption of their dominance and that their Big lumber-fueled Machine would assure him of 25 or 30 wins per annum), yet he wasn’t smiling. He cried. Nancy cried. It was on the front page of the Post. My sister had just begun an internship with an advertising agency that had Bausch & Lomb as an account. She clipped the pictures of them dabbing their eyes and mocked up an ad for soft contact lenses to show around the office. She was just being clever, but she picked the wrong week to start mocking Tom Seaver.

We were in the toilet already for ’77. Seaver could pitch his heart out, Kingman could connect on a semi-regular basis, Mike Phillips could do whatever it was that Mike Phillips might have done and we were going to have a tough time topping Montreal for fifth. We were in the toilet, but we should have all gone down together. And who knows? There was always 1978.

At least there would have been. The Mets were over for years to come. Seaver was as Red as they got. On Saturday the 18th, he appeared as if from out of a nightmare on the dingy mound at Olympic Stadium in Cincinnati grays, shutting down the Expos on the Game of the Week. NBC rounded up Marv Albert and Art Shamsky to broadcast. Two New Yorkers announcing that two days after wiping his eyes dry, the quintessential Met had thrown a three-hit, eight-strikeout complete game shutout. You couldn’t not look at Tom Seaver, whatever uniform he wore to work, and not see the Met within. I thought he deserved to have Bench, Rose, Morgan and Foster at his disposal. With hindsight, I thought wrong. Tom Seaver never, ever should have been let go.

What a pity. What a tragedy. Nobody died is the best I can say about it.

Ladies and gentlemen, Queens grew quiet. Again, what was the point? Except for the odd Jacket Day, plenty of good seats became available. The Mets, the locus of New York’s baseball coverage as recently as 1975 and still considered a contending entity as late as March, fell off the face of the city. There was a better chance the lights would go out for 24 hours than there was that you could spot bright faces congregating at Shea Stadium. The action had moved to another borough and would remain there well into the 1980s.

But like I said, I lived through it. Gritted my teeth and lived through it. Sucked it up and lived through it. The house wouldn’t be rebuilt for an eternity, but I hung in. I never stopped idolizing Tom Seaver but I never stopped rooting for his old team, my continuing team. The names were suddenly unfamiliar and the mix wasn’t particularly promising. To paraphrase from a General Washington dispatch dramatized in 1776, I began to notice that many of the Mets were lads under 25 and old men, none of whom could truly be called ballplayers. “Bring Your Kids to See Our Kids” was the Mets’ pitch. Without Seaver, pitching was the last thing they should have tried.

But I was a Mets fan. I couldn’t be one of those people who switched allegiances or swore off this habit. What was I going to do — stare out the window and wait for death? I was 14, but I was fully made. And unlike Tug and Cleon and Rusty and Yogi and Tom and Dave and Mike, made fans never leave the life.

I didn’t care for Tom Seaver’s absence, what it represented as regarded the immediate prospects of my team and how little it indicated management cared about its product or its customers. That Jack Lang story in The Press said the Mets thought they had a shot at Don Sutton. A thorough 30-year retrospective by Brian Costello uncovered Torre’s recollection that future Dodger star Pedro Guerrero was waiting in the wings. Instead Grant and Joe McDonald took the 99-cent store approach to rebuilding: quantity, quantity, quantity, quantity…and so cheap!

I came to pull for Steve Henderson, Doug Flynn, Pat Zachry and Dan Norman in short order. But I never should have had to.

Next Friday: Mighty Casey’s last at-bat.

|

|