You might know Ken MacKenzie was the only Met pitcher to post a winning record in 1962. As calling-card facts go, it is distinctive and enduring and, within the context of a team that inspired its beat writers to track what Leonard Koppett dubbed the “neggie” or negative statistic (like the Mets’ failure to win a single game on any Thursday), unusually upbeat. Less commonly referenced is that Ken was also the only Met pitcher to post a winning record in 1963, a year during which he was traded, and that no Met pitcher who remained or emerged in 1964 posted a winning record. For three seasons, Ken MacKenzie provided the only concrete evidence that the Mets could win more than they lost.

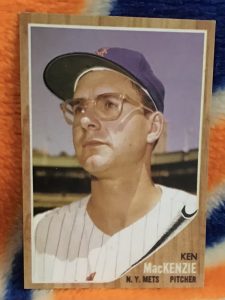

Few are the Original Mets who symbolize winning in orange and blue, but you can’t take away from Kenneth Purvis MacKenzie his distinction, nor would have Ken, who passed away Thursday at age 89, downplayed his association with our tribe. If you trailed a vehicle tooling around the Tri-State Area with a Connecticut plate reading 62 MET in recent years, you were following in the tracks put down by the automobile of Ken MacKenzie.

One day after stocking the prospective Original Mets with 22 personnel possibilities from the 1961 expansion draft, George Weiss returned to his shopping and purchased Ken’s contract from the Milwaukee Braves. The lefty reliever became a member of Casey Stengel’s very first pitching staff, the one that broke camp in St. Petersburg, flew to St. Louis to begin the franchise’s official existence, and came home to the Polo Grounds to reinstate National League baseball in New York. Ken’s Met debut occurred on April 15, 1962, the club’s fourth game ever. Curiously, the native of Gore Bay, Ontario, was the second Canadian in Mets history. Ray Daviault, who pitched in the Home Opener on April 13, hailed from Quebec.

The Mets reserved two spots for pitchers from the Great White North, yet they were heading south at a precipitous rate. The Mets’ first nine games resulted in nine losses. MacKenzie worked in three of those, though he steered clear of any deleterious decisions himself until May 4, when he took the L in a 6-5 defeat at Philadelphia. But Ken’s days would come.

The first of them arrived May 19 in Milwaukee, versus the team that sold him to the Mets. Ken let the Braves know he remembered them by throwing a pair of scoreless innings that culminated in retiring Hank Aaron on a grounder to short. The Mets were behind, 5-2, when MacKenzie entered, and he hadn’t extended their deficit a whit in the sixth and seventh. Holding the fort can be fortuitous, and so it was this Saturday in Cream City. Another ex-Brave, Frank Thomas, tripled to lead off the visitors’ eighth. A rally commenced. Down 5-4, Stengel pinch-hit Richie Ashburn for Ken. Whitey came through with a single. Charlie Neal crossed the plate. The game was tied. Jim Hickman then batted with one out and delivered a sac fly to score Rod Kanehl. Ken MacKenzie was the pitcher of record on the long side. Craig Anderson nailed the final six outs.

The Mets were 10-19, or 10-10 since losing those first nine. Ken MacKenzie was 1-1. Having tasted variations of .500, Kenny and the Mets the very next day decided they wanted more out of life. Being the Mets, they’d have to struggle for it. They trailed the Braves, 5-1, at County Stadium in the seventh when MacKenzie came in once more. The seventh inning on May 20 reflected his success of the day before, with Ken striking out Aaron again. The Mets trimmed the Braves’ lead in the eighth to two runs and stuck with their lefty in the bottom of the inning. Ken did not give up a run. In the top of the ninth, Casey again pinch-hit Ashburn for MacKenzie. Ashburn again singled, sparking a four-run uprising that vaulted the Mets into a 7-5 lead. Anderson again came on to protect what Ken had constructed. This time it wouldn’t be easy for Craig, as Hammerin’ Hank doubled home his brother Tommie, but the Mets held on to win the first game of this Sunday doubleheader, 7-6, and they’d grab the nightcap as well.

The Mets were in the midst of their very first three-game winning streak, and Ken MacKenzie was 2-1. “The darlings of New York — an odd-lot collection of expendables,” reported Bob Green of the Associated Press, “suddenly are the hottest team in baseball.” The relief pitching Stengel was getting from Ken, among others, was proving a “thorough-going pleasure,” according to Dick Young in the Daily News. For the briefest of instances, despite Green’s assessment that “there is still an air of the Keystone Cops about this crew that lost nine straight at the start of the season — they flounder about and sometimes run into each other,” it appeared the 1962 Mets would have to be taken somewhat seriously. They’d won nine of their previous twelve games and led two teams (Houston and Chicago) in the standings. “Somehow,” the man from the AP marveled, “Stengel, the old master manipulator, has them winning.”

Well, that didn’t last. A seventeen-game losing streak awaited as soon as the Mets left Milwaukee, and tenth place was a sure thing by the end of May, yet Ken MacKenzie was destined to make his mark in the other direction. On July 2 in San Francisco, Ken rescued Anderson for a change, setting down the Giants in order in the seventh inning after Craig turned a 4-1 Met lead (built at Juan Marichal’s expense, no less) into a 5-4 Met deficit. Another savvy pinch-hitting choice by Casey the master manipulator — this time Rod Kanehl reaching on an error as he batted for MacKenzie — contributed to a four-run eighth that provided the Mets the winning margin in an 8-5 triumph. Ken’s record was raised to 3-3.

The next victory in the MacKenzie collection was a doozy. Four innings of relief were punctuated by Ken himself singling in Joe Christopher to give the Mets a 9-6 lead, an insurance run that proved vital in what turned into a 9-8 final. With his arm and his bat, MacKenzie could now claim a 4-3 record.

Casey tried his lucky lefty as a starter in a Polo Grounds doubleheader on August 18. Not much luck for Ken in that capacity, and he’d be 4-4 by the time that game versus the Cardinals was over. Yet one more decision was in the offing as 1962 rolled on. The day that distinguishes MacKenzie among all Mets pitchers until 1965 (when Jim Bethke, Darrell Sutherland Dick Selma all finished over .500) is August 22, a home date versus the Giants. A home date versus the Giants in 1962 was no matter of playing out the string. San Fran was charging hard to catch up to L.A. at the top of the NL standings. And even if neither the Giants nor Dodgers was battling for a pennant, Mets fans remembered who left their town high and dry in 1957. “Every close Mets’ game against the Giants or Dodgers,” Stan Isaacs wrote in Newsday at the time, was tantamount to “another version of the ‘little World Series.’”

In this classic of the genre that drew 33,569 paying customers, the Mets led the Giants by three heading to the eighth. Alas, what Isaacs termed “the creeping dread of catastrophe” was also in attendance beneath Coogan’s Bluff. Bob L. Miller had handled the former neighborhood residents for seven innings, but Bob was burdened by an 0-10 record, and the Mets were 31-95 entering this particular Wednesday night, which is to say Met catastrophe didn’t necessarily creep in on little cat feet. Miller issued a pair of walks to start the eighth, then secured a groundout, then faced Willie Mays.

Facing Willie Mays didn’t often end fabulously for a pitcher, as Miller could attest after allowing an RBI single to the Say Hey Kid. The Giants were now down by two, they had two on and Orlando Cepeda due up. Miller time was over. MacKenzie time was at hand. Ken was a lefty, and Cepeda was a dangerous righty, but Casey had his reasons, all of them tied to his faith in the Canadian southpaw.

”He gets those righties out better than lefties and now he’s getting the lefties out. That man is getting close to being a big league player. I mean just because you’re playing for us don’t mean you’re a big leaguer, but he’s getting there.”

Which is great, except Cepeda singled to center to score Chuck Hiller and move Mays up to third, from whence Willie came home when the next batter, Felipe Alou, grounded out. The game was knotted at four. Bob Miller’s shot at getting his first win was erased by MacKenzie’s not so hot outing.

If Ken couldn’t preserve a win for his beleaguered teammate, he could at least make it up to the rest of the team. Stengel had MacKenzie bat for himself to lead off the home eighth. He made contact, which is so much better than striking out, because you never know what will happen when you put the ball in play. In this case, an error happened, charged to Giant second baseman Hiller. MacKenzie was on first, carrying the potential go-ahead run. Its potential grew in possibility when Casey replaced Ken on the basepaths with Joe Christopher. The Ol’ Perfesser called on pinch-runners 86 times in 1962, still the most in any season in Mets history. “With a chance to go ahead, Stengel operated like the master he is,” Isaacs observed. “He still makes the masterful moves with the Mets, but the boys just don’t ‘execute’.”

On the night of August 22, they did. Richie Ashburn drew a walk to advance Christopher to second, and Neal singled to drive speedy Joe home with the lead run. Up 5-4, and not taking an opportunity to beat a contender (or anybody) lightly, Stengel inserted Roger Craig to pitch the ninth. Roger Craig was the ace of the starting rotation in 1962, but what exactly was Casey gonna save him for that was bigger than this? Roger indeed notched the save…with defensive help from none other than Marv Throneberry at first. Following Jose Pagan’s leadoff single, Marvelous Marv made a nifty stab on a sharp grounder off the bat of Willie McCovey and started a clutch 3-6-3 double play that set the stage for the final out.

Isaacs, ever ready to interpret the deeper meaning of Mets baseball in its infancy, heard “a grown man in the upper right field stands blurt, ‘Oh boy, we saw the Mets beat the Giants,’” illustrating that “for people who are with it, these Met games are an experience over and above the mere pleasure of watching baseball. Grown men at Yankee games or My Fair Lady or Little Orchestra recitals don’t come away with the gleam in the eye of the man who exulted at the good fortune of having seen the Mets beat the Giants for the fourth time in seventeen games.”

Amid the enthusiasm attached to such an outcome, MacKenzie’s won-lost mark rising to 5-4 might not have seemed a particularly big deal. let alone rated an “oh boy”. Even in 1962, when pitchers were judged mainly by their accumulations of Ws and Ls, it was understood relievers sometimes happened to benefit from right place/right time syndrome to record their victories, particularly when a pitcher left a game trailing or tied after giving up key runs himself. Sometimes the pitcher on the hook sat back and enjoyed the fruits of his team’s offense making everything better and him a winner. “Vultured” is how those wins tend to be described. But it’s a long season, and teammates do pick up for teammates. This team was on its way to losing three times more often than it won, yet one pitcher on this team was the pitcher of record nine times and came away with one more win than loss on his ledger. If it was that easy to achieve, some other 1962 Met would have achieved something like it. None did.

Five-and-four was the record Ken MacKenzie would keep for the rest of 1962, and that’s the record by which he’d be recognized into baseball eternity. The 3-1 he cobbled together in 1963 would be less invoked as a piece of trivia, but, yeah, no other pitcher in the Mets’ second year had a winning record, either. Ken showed enough as a “big league player” to attract the interest of the contending Cardinals in the summer of 1963. St. Louis swapped Ed Bauta to the Mets to acquire MacKenzie while they were visiting New York. Ken had worn 19 as a Met. It was immediately issued to Ed. The pitchers themselves traded warmup jackets, with Ken shedding blue nylon in favor of red.

But Ken’s license plate nearly sixty years later didn’t read 63 CARD. He clearly relished his connection to that first bunch of Mets, and if being known as the guy who won for a team that made losing an art form was what people chose to remember, it beat being known as just another pitcher who lost a lot…or being mostly forgotten. He nodded along for decades when his other calling card, his status as the so-called “lowest-paid member of the Yale class of 1956,” was brought up to him. Going into professional baseball wasn’t a path to riches for an Ivy Leaguer or any leaguer back then. Embroidered within the legend of the first Yalie to pitch for the Mets (Ron Darling being the second) was Stengel’s advice to bear down against tough batters like he was facing “the Harvards”. Per MacKenzie, who would coach at his alma mater after retiring from baseball, that was no stray tossed-off trifle of Stengelese. Ken actually pitched very well against Yale’s archrivals, and MacKenzie said Casey knew that, much as Casey had a knack for knowing something about everything.

MacKenzie threw his first pitch in the majors for the Braves in 1960 and his last for the Astros in 1965. His tenure left him about a month shy of qualifying for the major league pension, and as a Yale alumnus not necessarily in the same league financially with classmates who pursued other endeavors, he put out feelers to his old teams in 1969, when he was 35, to see if there’d be room for him on the September roster in order to accumulate the requisite days he needed. He also checked in with the expansion Expos, given that they were ensconced in Montreal; he was Canadian by birth; and their enterprise was run by John McHale, who remembered him from their days together in Milwaukee, pre-Mets. McHale, operating a team that was going nowhere, brought Ken on board to finish out his career as an active pitcher. He threw only batting practice, but he earned his pension. He also had a pretty good seat for what had been unthinkable seven years earlier when he came into Shea Stadium with the Expos on September 10 and watched the Mets surge into first place. In 1962 and 1963, MacKenzie was the only Met with a winning record. In September of 1969, the Mets as a whole hardly ever lost. Despite wearing the uniform of the Expos, MacKenzie admitted to Isaacs he was quite happy for their opponents’ upturn in the standings. “I’ve always thought of the Mets as my team,” Ken said.

For the rest of Ken’s life, that sense of identity was clear, and not just if you saw his car. MacKenzie remained a generous sharer of stories about the Original Mets whenever he was asked to recall those days, a gift that grows in value when you realize there are only nine living Mets among the 45 who played for our team in 1962. They were just anecdotes, but they were the kinds of anecdotes that would otherwise disappear from the baseball discourse if he didn’t tell them. Pregame hands of bridge in which Ken and his pal Hot Rod Kanehl competed against two future Hall of Famers, Gil Hodges and Duke Snider. An unexpected compliment from batting coach Rogers Hornsby that “‘you’re not a bad hitter, you put the bat on the ball.’ And usually, he didn’t talk to anybody.” Ken would confirm, as best he could as the details blended into Met mythology, the old favorites about Yale, and going 5-4 when everybody else was going 35-116 combined. Historical retellings are ultimately copies of copies of copies once the source material is no longer within our grasp. Here was a primary source, still telling it like it was.

When the Mets performed their biggest mitzvah as a franchise and invited back 65 of their alumni for a blowout sixtieth-anniversary celebration at Citi Field in 2022, the first Met returnee Howie Rose introduced was Ken MacKenzie. Ken had helped promote the revival of Old Timers Day all year, joining Jay Horwitz’s podcast over Zoom and granting a lengthy interview to the Hartford Courant. When the big day approached in late August, Jay later revealed, Ken checked himself out of the hospital to make sure he’d be there. He had to be wheeled to the foul line, but this Original Met wasn’t gonna miss this occasion.

A grown man in the upper left field stands that afternoon didn’t blurt anything in the moment, but he did applaud heartily, thinking to himself, in so many words, “Oh boy, I’m seeing the first Met to post a winning record.” There were, that grown man is certain, more than a few gleams in more than a few eyes when Ken’s name was called.

It’s almost getting to the point where I look forward to the passing of the remaining early Mets so I can read about them in depth here. Thanks once again for revisiting my youth. Boy that 1962 Hot Streak was fun!

About that Yale comment. In Lindsay Nelson’s Hello Everybody, he tells the story of MacKenzie negotiating his proposed 1963 salary with George Weiss. Ken pulled the “I’m the lowest paid member of my Yale graduating class” card, to which Weiss replied: “Maybe so, but you also had the highest ERA.”

Thanks again.

I never heard of this guy til reading this, thanks Greg!

I never heard of this guy til reading this, now I love him, thanks Greg!

Mr. McHale and the 1969 Expos were quite generous to Mr. Mackenzie by adding him to that September roster. Good for Ken! I believe these days, MLB management would be less magnanimous in that regard.

Players seem better represented via collective bargaining today, but that doesn’t make McHale any less of a mensch in this context.

Great story. Brings back many memories. Bob Miller (the left handed Bob Miller) winning on the next to last day of the 1962 season to avoid going 0-12. Choo Choo Coleman; Jay Hook……

As a New York Giant fan living in Brooklyn in 1957, Dodger fans and I shared the same angst when our teams left, and the same joy when the “getting near to be a big league player(s)” Mets arrived. To this day, I enjoy Mets victories over the Dodgers and Giants more than against any other team….well maybe the Yankees(lol).

[…] Prince wrote about the late Ken MacKenzie as only Greg Prince […]