Before he became my blogging partner of twenty Springs and counting, Jason used to torture me with a hypothetical. What if I could guarantee the Mets a world championship by not seeing or hearing any of the season that made them world champions? As we batted this devil’s bargain around between pitches, I searched for loopholes. Could I get updates at least? Could someone slip me scores under the door of wherever I was holing up? Would there be a commemorative VHS so I could eventually take in what I’d missed?

I don’t know that we ever defined all the conditions or if I ever fully answered the question, but long before I was asked it, I had tried my best to tolerate the Mets succeeding wildly with me in absentia. A world championship wasn’t involved, and it’s not like I was totally in the dark for six months, yet I knew the situation I’d traversed wasn’t ideal. Had I experienced more of this marvelous season from my usual vantage point of consuming most every pitch of most every game, I believe it would rate a lot higher among MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT. As is, I am quite fond of what I was able to get out of it, and what it portended for the Mets’ future.

With apologies to Elton John’s lyricist collaborator Bernie Taupin, the words I know, the tune I hum — yet I can’t tell everybody that the 1984 Mets are my song. But, oh, how it feels so real.

With further apologies to Foreigner, I’d been waiting for a year like that to come into my life. Nineteen Eighty-Four was a long time coming. A looooooong time. All I did was get older while the Mets weren’t getting better between the runup to June 15, 1977, and the aftermath of January 20, 1984. The same kid who loved the Mets in eighth grade, even while the Mets were trading Tom Seaver, was still loving the Mets, even while the Mets were losing Tom Seaver anew in something called the compensation pool, even while the description of myself as a “kid” grew less and less apt. Your accumulation of years is a larger percentage of your life when you’re younger, regardless that you haven’t lived that many years, meaning the Mets being terrible for seven years meant they’d been terrible FOREVER. If I hadn’t been permanently blinded by the orange and blue before I hit adolescence, maybe I would have stopped waiting once I had reached early adulthood.

Of course that was never going to happen. I was going to wait as long as it took for the Mets to stop being what they’d been and start being something else. Then the moment I’d been waiting for arrived, and the Mets couldn’t wait for me. Nor should they have. We’d all waited too long for the Mets to emerge from the mire in which they languished for seven seasons. “Go,” I’d tell them had they asked me. “Don’t hold off on what you need to do just because following the spring semester of my junior year of college at the University of South Florida, I won’t be coming directly back to New York like I usually do, and I therefore will be not where I oughta be at that moment when you, once and for all, stop being the dregs of the National League East and start being the kind of team I’ve dreamed about you being since I was in junior high. No, no, you go ahead without me. I’ll catch up.”

They didn’t ask. Just as well.

I doubt I enjoyed the best parts of the 1984 Mets any less than anybody who was privileged enough to be proximate to them as they transpired. I know I enjoyed them differently. The lyrics of that transformational season I do know, and the melody I can hum, even if, deep down, I have to admit what I’m belting out is a karaoke version.

To be clear, newspapers existed where I was, and the news on television included sports reports with videotaped highlights of select baseball games, and once in a while there’d be a national telecast or something on the radio. Mets information was available to the consumer diligent enough to seek it. But it wasn’t the same as being in New York as April turned to May and spring flowed into summer and the laughingstock/afterthought Mets transitioned in a blink to the truly amazing Mets who fought for and took hold of first place.

First place!

Real first place!

Not first-week first place or first-month first place before an inevitable descent to well below first place.

After 1973 and prior to 1984, the Mets’ latest first place record came 30 games into a season (19-11 in 1976). There’d be a few brief feints at upward mobility to tide me over, but mostly a lot of bad, bleeping baseball to overwhelm my optimism. Last place or next-to-last place had been the rule from 1977 forward, save for the second half of the split season of 1981, when I took a little too much delight in the Mets finishing a spirited fourth.

Then 1984 and first place! Or so I read in the papers from a distance. To be fair, I would have missed the promising start to this promising season, regardless of my summer plans. USF’s standard academic year annually included April. I always missed Opening Day. I missed the introduction of George Foster in 1982 and the (temporary) homecoming of Seaver in 1983. I accepted that, just as I accepted missing the final month of every season, because my academic year annually began at the tail end of August.

Then 1984 and first place! Or so I read in the papers from a distance. To be fair, I would have missed the promising start to this promising season, regardless of my summer plans. USF’s standard academic year annually included April. I always missed Opening Day. I missed the introduction of George Foster in 1982 and the (temporary) homecoming of Seaver in 1983. I accepted that, just as I accepted missing the final month of every season, because my academic year annually began at the tail end of August.

In between, I’d drive my ass off to get back to New York from Tampa in time for all of May and all of June and all of July and most of August. That’s the majority of a baseball season. I’d settle in for my first game on TV and it was like I was never gone — and the Mets never got better.

Thus, it’s early April in 1984 and I’m straining to spy the Mets from afar, just as in ’82 and ’83, and they lose on Opening Day in Cincinnati, which is a shame, given that winning on Opening Day is usually one of our dependable highlights. Yet the ’84 Mets win their next six, all on the road, and that includes the debut of 19-year-old Dwight Gooden, whose potential I’m clued in on, because he’s from Tampa and he gets covered in the Tampa Tribune, plus I saw him pitch in March in St. Pete. Having Spring Training access while a college student in the Bay Area surely helped make up for the lack of Aprils and Septembers in New York. (Don’t cry for me, Temple Terrace.)

The Mets continue to succeed as they haven’t succeeded in ages, which is to say they don’t fall apart after a good first week or two. Their record never drops below .500, and they are in and out of first place as my summer semester at USF gets underway. One summer semester is a requirement. I wouldn’t have chosen to hang around Tampa as the Florida weather got even hotter. I wouldn’t have chosen to be far from New York as the Mets came into their own.

My absorption of box scores and wire copy has never been more purposeful or intense. Without the dragnet coverage provided by the beat writers in the hometown papers I’ve never missed more, I’m left to piece together what’s going on. “Chapman” is a name I see playing “2b” for the Mets. Huh? Is that Kelvin Chapman? Really? Kelvin Chapman from 1979? He’s still around? He is. He’s platooning with Wally Backman, whose presence at 2b isn’t a shock, as he’s been up and down with the Mets since 1980, but wasn’t Brian Giles the future at second base coming out of last year?

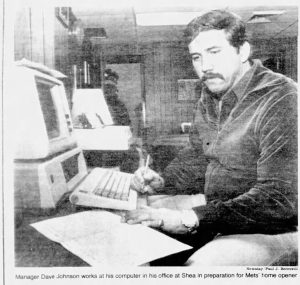

Stuff like that eventually explains itself. The computer-fueled managerial ability of Davey Johnson, who the Mets promoted from Tidewater in October of 1983 while I was immersed enough in my studies and so forth to not process what an epic hire it might be, shines through in the standings and the occasional stories I catch up on. In reflecting on his first season a year after the fact, specifically the lack of expectations surrounding the 1984 Mets before they’d played a single game, Davey told Jack Lang in the Sporting News, “I used to get a kick out of it when I picked up the papers in the Spring and saw where people were picking us for fifth and sixth. I knew a lot of people were going to be surprised because I knew we had a lot better team than they realized. It may have come together a little sooner than I anticipated, but I knew we were going to be a good team.”

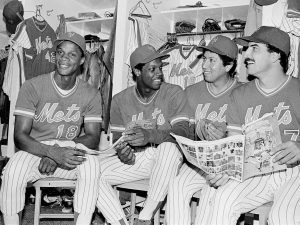

In 1984, Davey knows more than everybody. He’s platooning two minor league infielders at second and getting what he needs. He’s resurrecting Ron Gardenhire at short, who’s usurped the future of Jose Oquendo. He’s trusting in Hubie Brooks at third and moving incumbent center fielder Mookie Wilson down the order, and it’s working. Mike Fitzgerald has stepped up to squat down once hot catching prospect John Gibbons encounters injury. Foster looks alive in left. Darryl Strawberry isn’t homering every time up, as I thought might be possible, but just knowing our budding superstar right fielder might go deep during any at-bat is a boost. Keith Hernandez at first base is all we hoped he’d be when he came over from St. Louis.

In 1984, Davey knows more than everybody. He’s platooning two minor league infielders at second and getting what he needs. He’s resurrecting Ron Gardenhire at short, who’s usurped the future of Jose Oquendo. He’s trusting in Hubie Brooks at third and moving incumbent center fielder Mookie Wilson down the order, and it’s working. Mike Fitzgerald has stepped up to squat down once hot catching prospect John Gibbons encounters injury. Foster looks alive in left. Darryl Strawberry isn’t homering every time up, as I thought might be possible, but just knowing our budding superstar right fielder might go deep during any at-bat is a boost. Keith Hernandez at first base is all we hoped he’d be when he came over from St. Louis.

And how about that pitching? Gooden. Ron Darling, who debuted last September when I wasn’t suffering nearly as much Mets separation anxiety. Walt Terrell, part of the same trade that brought Darling from Texas for former Flushing heartthrob Lee Mazzilli. Mazzilli’s on the Pirates now. There’s a game in Pittsburgh, on June 6, when Gooden — they call him Doctor K and hang K’s for his strikeouts at Shea, I learn — flirts with the first no-hitter in Mets history. He doesn’t get it, and the Mets give up their 1-0 lead in the eighth, yet “Doc” is still on the mound in the ninth, trying to hold a 1-1 tie in place. The Mets have good relievers like Jesse Orosco and Doug Sisk, but Davey trusts Dwight the way managers have always trusted aces.

Mazzilli, who wore 16 for the Mets before Gooden did, walks to lead off the bottom of the ninth and then steals second. A ground ball moves him to third. An intentional walk is ordered to Bill Madlock. Johnson tells his rookie pitcher to take on the main Buc slugger Jason Thompson. Unfortunately, Thompson drives a ball to Wilson in center. Mookie still doesn’t have much of an arm. Mazzilli still has enough legs. Lee beats the throw. Fireworks go off above Three Rivers Stadium. Pirates win, 2-1.

Except Davey Johnson is clever enough to put on an appeal play and short-circuit the celebration. Fitzgerald throws to Brooks at third. Doug Harvey calls Mazzilli out in an 8-2-5 double play. Lee left the bag too soon (similar to his timing in departing Queens before he could be part of a contending Mets team). Coach Frank Howard says later, “Anyone with eyes in his rear end could have seen it.”

No part of me saw this incredible reprieve from the governor. I had to read about it in the Tribune. I had to read, too, that the Mets and Pirates played on until the thirteenth, when Backman sparked the go-ahead rally and Tom Gorman — another fringe Met off my outdated radar — saved the 2-1 victory. I was extremely happy to have the win and the momentum, but I wished I could have embellished it by walking around after learning of it and bumping into people who also knew about it and cared about it. That just wasn’t how it was going to be when you lived somewhere else when the Mets were riding high.

The important thing was the riding high, I told myself.

On June 21, the Mets and Phillies played one of the craziest games I never saw or heard in all my years as a Mets fan. It’s probably more of a legend in my mind because a) I didn’t see or hear it; b) I was determined to run up my Sports Phone bill to stay abreast of it the weekday afternoon at Shea while it was in progress; and c) I was on one of those multiple all-nighter jags I would get on during college when assignments and tests and work all collided to make sleep a luxury. The 1984 Mets were Vivarin for my soul.

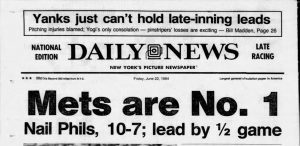

The upshot of June 21 was the Mets had a 6-1 lead; fell behind, 7-6; and stormed back to win, 10-7. I don’t know if “stormed back” was ever more appropriate. The Mets had stormed back from the depths of the NL East in 1984 and now they were beating the team that had been the embodiment of subjugation. The Phillies were at the end of their line as a formidable foe, but they’d won the pennant the year before and so many division titles since 1976. There was a passing of the torch going on here, I decided. The Phillies, by losing, fell out of first place. The Mets, by winning, took over first place. Not with a joke record, either, like when the Mets earned a first-place headline from the Post in 1979 for winning on Opening Day. The Mets were 36-27. Fewer than 100 games remained to the 1984 season and the Mets were in first place. You could calculate a magic number if so inclined. The fans at Shea, I read in the thin but essential National Edition of the Daily News, chanted WE’RE NO. 1! as they might have when Rusty Staub and Ron Hodges were contributing to miracles for the 1973 Mets. As it happened, Staub and Hodges delivered key RBIs to topple Philadelphia in 1984. It was all so perfect.

The upshot of June 21 was the Mets had a 6-1 lead; fell behind, 7-6; and stormed back to win, 10-7. I don’t know if “stormed back” was ever more appropriate. The Mets had stormed back from the depths of the NL East in 1984 and now they were beating the team that had been the embodiment of subjugation. The Phillies were at the end of their line as a formidable foe, but they’d won the pennant the year before and so many division titles since 1976. There was a passing of the torch going on here, I decided. The Phillies, by losing, fell out of first place. The Mets, by winning, took over first place. Not with a joke record, either, like when the Mets earned a first-place headline from the Post in 1979 for winning on Opening Day. The Mets were 36-27. Fewer than 100 games remained to the 1984 season and the Mets were in first place. You could calculate a magic number if so inclined. The fans at Shea, I read in the thin but essential National Edition of the Daily News, chanted WE’RE NO. 1! as they might have when Rusty Staub and Ron Hodges were contributing to miracles for the 1973 Mets. As it happened, Staub and Hodges delivered key RBIs to topple Philadelphia in 1984. It was all so perfect.

Except for me not being anywhere near it.

My summer semester ended as the All-Star break was concluding. The Mets were the first-place Mets as baseball’s best gathered at Candlestick Park, sending their largest contingent of players to date to the Midsummer Classic. Hernandez on the bench. Orosco in the pen. Strawberry in the starting lineup (his Rookie of the Year award from the year before and unforgettable name might have boosted his vote total). And Gooden. Gooden was 19 and pitching in the All-Star Game, striking out every American Leaguer he faced in the fifth inning and giving up no runs in the sixth, either. I watched from a booth in an off-campus pub, ostensibly enjoying a post-finals night out with a couple of friends whose attention I kept directing at the TV over the bar. I Metsplained to them who Dwight Gooden was and why what he was doing was so stupendous. They nodded politely before steering the conversation back to another topic.

My summer semester ended as the All-Star break was concluding. The Mets were the first-place Mets as baseball’s best gathered at Candlestick Park, sending their largest contingent of players to date to the Midsummer Classic. Hernandez on the bench. Orosco in the pen. Strawberry in the starting lineup (his Rookie of the Year award from the year before and unforgettable name might have boosted his vote total). And Gooden. Gooden was 19 and pitching in the All-Star Game, striking out every American Leaguer he faced in the fifth inning and giving up no runs in the sixth, either. I watched from a booth in an off-campus pub, ostensibly enjoying a post-finals night out with a couple of friends whose attention I kept directing at the TV over the bar. I Metsplained to them who Dwight Gooden was and why what he was doing was so stupendous. They nodded politely before steering the conversation back to another topic.

There was another topic? What was more worth talking about than what the Mets were doing? The Mets had finished out the first half of 1984 by sweeping a five-game series from the Reds at Shea and tossing their caps to the fans in the box seats upon completion of their rampage. I practically panted as I stared at the agate type and gleaned assorted details in the Trib, my eyes lighting up the same as they did in a muffler shop waiting room where I picked up a recent issue of Sports Illustrated and found a feature story on the Mets as a revelation and Gooden as a Metropolitan phenomenon. “He’s a happening in New York,” the article said, and I wondered how he and they could be happening without me.

There was another topic? What was more worth talking about than what the Mets were doing? The Mets had finished out the first half of 1984 by sweeping a five-game series from the Reds at Shea and tossing their caps to the fans in the box seats upon completion of their rampage. I practically panted as I stared at the agate type and gleaned assorted details in the Trib, my eyes lighting up the same as they did in a muffler shop waiting room where I picked up a recent issue of Sports Illustrated and found a feature story on the Mets as a revelation and Gooden as a Metropolitan phenomenon. “He’s a happening in New York,” the article said, and I wondered how he and they could be happening without me.

Finally, on the evening of July 14, I pulled into the driveway of my family’s house on Long Island after a two-day drive, raced inside, greeted my parents, and turned the TV to Channel 9. The Mets were playing the Braves in Atlanta. Mets announcers were telling me all about it. Mets reporters would expand on it in the morning. The Mets won, 7-0, and increased their lead over their new rivals, the Cubs, to a game-and-a-half. Everything was, at last, as it should be.

It stayed that way for a couple of weeks. The Mets came home a few days after I did and I got to see them in person. Just showed up at the ballpark with my friends and lined up for tickets for the game that night. The line was way longer than it had been in previous summers, but we got in. The seats were way the hell up in the Upper Deck, but it was a pleasant change from sitting anywhere you wanted to watch a lousy team nobody wanted to see. The guy who ran Mets ticket sales confirmed the obvious for Lang: “It’s great to have a big advance sale, but you know you’re going good when people decide the day of the game they want to see the Mets play.” The first-place Mets engaged in another back-and-forth battle, this time with the Cardinals. We beat them in ten, 9-8, Hernandez sticking it to Neil Allen for the game-winning RBI, symbolism that nobody had to explain to the throng of 36,749. This wasn’t Tampa. We — we — chanted WE’RE NO. 1! like they did in June. I really was home.

It stayed that way for a couple of weeks. The Mets came home a few days after I did and I got to see them in person. Just showed up at the ballpark with my friends and lined up for tickets for the game that night. The line was way longer than it had been in previous summers, but we got in. The seats were way the hell up in the Upper Deck, but it was a pleasant change from sitting anywhere you wanted to watch a lousy team nobody wanted to see. The guy who ran Mets ticket sales confirmed the obvious for Lang: “It’s great to have a big advance sale, but you know you’re going good when people decide the day of the game they want to see the Mets play.” The first-place Mets engaged in another back-and-forth battle, this time with the Cardinals. We beat them in ten, 9-8, Hernandez sticking it to Neil Allen for the game-winning RBI, symbolism that nobody had to explain to the throng of 36,749. This wasn’t Tampa. We — we — chanted WE’RE NO. 1! like they did in June. I really was home.

Perfection fizzled in the days ahead. The Cubs took three of four in the ensuing series at Shea, then swept four from us at Wrigley to seal off first place once and for all, taking a bit of the edge off my excitement. So now I’m here and you start losing? You do know I was looking forward to you and me spending quality time together in first place? Yet the memory of 1984 never goes breaking my heart, We were en route to 90 wins and a solid second-place finish, and Gooden — did I mention he was 19? — was exploring a universe of his own, really racking up the strikeout numbers as the schedule wound down. Nevertheless, it became evident to me that I had missed the best part of the season by fulfilling my academic requirement. The five weeks I was around, the Rising Stars the contemporary ad slogan urged us to Catch were in something of a holding pattern, and the Mets mostly seemed to be on the road. Their victory tour didn’t go any better than the Jacksons’. I rushed back to Shea to catch three of the last four games I could in mid-August, versus the Pirates. We lost two of them. The one win was a Gooden win. (Don’t cry for me, Massapequa.) I thoroughly annoyed whoever sat behind me with my standing and clapping with two strikes so I could properly acknowledge those K’s going up in that Korner that was all the rage. Like the foam finger I bought and the wave I considered charming enough to participate in the first time it washed over my section, I wanted to reach out and touch every totem of the 1984 Mets.

Perfection fizzled in the days ahead. The Cubs took three of four in the ensuing series at Shea, then swept four from us at Wrigley to seal off first place once and for all, taking a bit of the edge off my excitement. So now I’m here and you start losing? You do know I was looking forward to you and me spending quality time together in first place? Yet the memory of 1984 never goes breaking my heart, We were en route to 90 wins and a solid second-place finish, and Gooden — did I mention he was 19? — was exploring a universe of his own, really racking up the strikeout numbers as the schedule wound down. Nevertheless, it became evident to me that I had missed the best part of the season by fulfilling my academic requirement. The five weeks I was around, the Rising Stars the contemporary ad slogan urged us to Catch were in something of a holding pattern, and the Mets mostly seemed to be on the road. Their victory tour didn’t go any better than the Jacksons’. I rushed back to Shea to catch three of the last four games I could in mid-August, versus the Pirates. We lost two of them. The one win was a Gooden win. (Don’t cry for me, Massapequa.) I thoroughly annoyed whoever sat behind me with my standing and clapping with two strikes so I could properly acknowledge those K’s going up in that Korner that was all the rage. Like the foam finger I bought and the wave I considered charming enough to participate in the first time it washed over my section, I wanted to reach out and touch every totem of the 1984 Mets.

I noticed during my month-plus in New York a few other things were changing without telling me. Little things. A new shopping center opened in the center of Long Beach, cosmetically improving the immediate neighborhood; the Waldbaum’s from two blocks east moved in. My neighbor was sunbathing to a radio station I hadn’t heard before, Lite-FM; 106.7 on the dial had switched formats over the winter. When I used a pay phone, it suddenly cost more than a dime to make a call. I understood Queens was getting a new area code — 718, something to remember for those thinking about connecting to 507-TIXX. For better or worse, the kind of change you might not pick up on if you’re around all the time was in the air. I was glad the Mets were a part of it for the better.

My senior year at USF beckoned at the end of August. I kept tabs on the Mets as best I could, deluding myself for as long as the math would allow that the Cubs would blow it and we’d pass them, because they blew it and we passed them in 1969…but 1984 wasn’t quite 1969. As an arc, however, it was the closest thing we’d had to it in fifteen years, and if you don’t think that’s Amazin’, then you weren’t exposed to at least some of it. It was the year that so needed to happen, the year that couldn’t wait one more inning for its most ardent fan to pull up a chair and soak it all in. Geography was more of an obstacle to Metsian immersion than it would be once developing technology collapsed barriers. Change was coming where that was concerned, but not with lightning speed. My college curriculum included a computer class that involved punch cards. Try to log into an out-of-town broadcast with those.

After the 1984 season was over, I had to put up with being in a place my team wasn’t for just a little longer. The Mets and I would get together for good soon enough. Something splendid had begun, and once I graduated, in April of 1985, I’d make damn sure that I’d be on its scene.

The splendidness has waxed and waned since. I’ve never left.

The splendidness has waxed and waned since. I’ve never left.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City

It’s pretty funny that the photo caption says “Davey Johnson works at his computer…” while he writes stuff down with a pen and paper. I guess “works at his computer” had a different meaning 40 years ago.

1984 was a lot of fun at Shea.

I got my driver’s license that year specifically so I could go to Shea whenever I wanted.

I too had a computer class a couple of years later with the punchcards. Sometimes it got better reception than Channel 2.

Who you gonna call?

Cub-Busters!

Thanks for taking the time put together this series, Greg. Terrific off-season content.

A fan since I bought a Topps rack-pack in 1974 and got a Seaver and Mets team card, 1984 was definitely one of my favorite seasons, with Doc and Davey on the scene and full seasons of Darryl and Keith. So much fun. I couldn’t wait for each game to start. I remember grilling burgers and dogs and playing Wiffle ball in the parking lot before July 29 banner day doubleheader loss against the Cubs from which we never seemed to recover.

Cut school on a Wednesday to attend Closing Day matinee, when we beat Kooz in Stearns’ Shea finale. We hung out in the Diamond Club afterward for hours to celebrate a season that was a long time coming. How is it possible that was 40 years ago?

How is it possible that was 40 years ago?

Well, you know…time keeps flowing like a river, to the sea.

I think it was Hubie Brooks that made that observation. Bruce Boisclair, maybe.

It’s difficult to describe how hard it was to be a Mets fan between 1977-1983. It wasn’t that they were bad (and they were), it was that they were bad, hapless, and just plain embarrassing. Those seasons were all but over by Memorial Day, sometimes even Easter. Shea was a barren, garbage-strewn dump, as were the rosters. Then 1984 happened. That was a magical time, the first time I was old enough to appreciate the Mets playing actual meaningful, competitive baseball. Seeing them atop the standings…IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SUMMER…was just completely mind-blowing. Radical change was in the air. They ultimately fell short (f*ck Rick Sutcliffe) but still, it was electric.