En route from the bottom 60% of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT — Nos. 55–44 here; Nos. 43–34 here; Nos. 33–23 here — to the just plain Top 20 (expressed without a percentage sign because they are, in fact, Nos. 20–1), I need to make a stop in consecutive years to explore No. 22 and No. 21 on my list. It’s a convenient coupling and can’t possibly be coincidental, but I’m pretty sure the adjacent nature of these seasons in my ranking of favorites is just that.

The two seasons we are about to visit do exist adjacently in both my affections and their chronology. They are bound together by one ginormous event that was a huge factor in our baseball lives for 232 days. It (along with winter, one supposes) was the reason there was no baseball in that span. Then the ginormous event was over and receded into the backstory of our game, though not as far back as the two Met seasons it linked. These seasons are utterly anonymous in any garden-variety retelling of Met history, which may be just as well since they happened almost off the narrative grid that’s taken us from 1962 to the present. In their limited time as the present, both years were about new beginnings. The first of them didn’t take in such a capacity — that aforementioned ginormous event cut if off before it could gain traction; at least it stanched the bleeding of the season that preceded it. The second of them hinted at what was ahead, but doesn’t quite fit the role of harbinger of an era to come. A little here and there, perhaps, but it, too, doesn’t connect neatly to its relatively near future.

Yet here they are, on the edge of the Top 20, ranked above 33 of the Met seasons through which I have lived and rooted. I have maintained above-average affection for these two years despite their anonymity, or maybe as an ode to it. I know I lived them. I know I rooted during them. I remember ripples of gratification obscuring these seasons’ obvious imperfections. I liked these years a good deal then. To say I treasure them now might be an exaggeration, but I’m guessing they’ve stayed closer to my Met heart than they’ve hung around the Met heart of others. That’s just where I’ve kept them since I first found them roughly three decades ago, and it’s never occurred to me to shove them all the way into the back of my memory’s storage unit.

Keep the seasons nobody else thinks about handy. You never know when you’ll need them.

No World Series in 1994? The hell you say! I experienced my version of the Fall Classic throughout the spring and as much summer as the feuding factions of MLB would allow. My World Series pitted the Mets versus how bad the Mets could have been. Respectability captured the only Series that mattered in 113 games. Context was named MVP.

True, there was no actual World Series that year. I prefer to err on the side of “big whoop” where that widely bemoaned cancellation is concerned. When Commissioner Bud Selig announced more than a month after the Players Association struck Major League Baseball that the World Series was canceled, garments were rent and wails went up. Millionaires and billionaires arguing!!! How could they do this to the WORLD SERIES?!?! I’ll never watch another game!!! I was approximately 5% sympathetic, 95% STFU with that BS, except I probably didn’t use acronyms.

True, there was no actual World Series that year. I prefer to err on the side of “big whoop” where that widely bemoaned cancellation is concerned. When Commissioner Bud Selig announced more than a month after the Players Association struck Major League Baseball that the World Series was canceled, garments were rent and wails went up. Millionaires and billionaires arguing!!! How could they do this to the WORLD SERIES?!?! I’ll never watch another game!!! I was approximately 5% sympathetic, 95% STFU with that BS, except I probably didn’t use acronyms.

Yes, the World Series oughta be sacrosanct, but no more so than the regular season that sets its stage, which in 1994 had a curtain pulled down over it on August 11 after negotiations regarding a salary cap the owners wished to impose went nowhere. If you couldn’t get back to your schedule and play it to some sort of conclusion, why would a World Series matter? I start to care about the World Series in an earnest, nonpartisan way once the identity of the pennant-winners comes into focus. We were miles from those big reveals on August 11.

None of this had a darn thing to do with the Mets in 1994, which may also be why the World Series talk rang hollow with this diehard baseball fan. On the last night games were played, the Mets sat 12½ games from a postseason berth, the first time one was compelled to apply such nomenclature to baseball. Before 1994, we’d simply state how many games out of first place a team that wasn’t in first place was, and you had all you needed to know. But now, like every other sport, baseball offered side doors to the playoffs. The Wild Card was brand new in ’94, one per league. The Mets weren’t in the running for one of those. Nor, at 18½ games from the top of the NL East, was first place realistically attainable to them in their realigned division. The Expos were on fire and the defending Western Division champion Braves never lost a step when somebody finally decided to get geographically correct about their Georgia location. Let Expos fans and Braves fans and other teams’ fans regret the lack of a 1994 World Series. It wasn’t our problem. I was the prototype for football coach Jim Mora bellowing at the assembled Indianapolis media, “PLAYOFFS?” when a reporter dared ask him if his 4-6 Colts still had a shot at playing for the Super Bowl.

Yet I didn’t get mad that the Mets had no chance at any canceled playoffs, because the 1994 Mets were getting close to getting even in the winning percentage column. They succeeded wildly at not sucking all that much. T-shirts weren’t licensed and sold at Modell’s to celebrate the accomplishment, but I guarantee you if they had been, I’d have bought one. Not automatically expecting to lose can move theoretical merchandise.

The Mets’ record of 55-58 is a little misleading in communicating a sense of their ability to sustain stretches of competent baseball. They were surprisingly good in the first and final swaths of their limited season (18-14, 22-15), a stone drag in the ad hoc middle (15-29). Their composite mark left them four wins shy of their 59-victory sum from 1993, which, it should be noted, was compiled across a slate of 162 mostly miserable games. There’s that most valuable context coming to the fore: it was no longer 1993 for the Mets. That year’s team was a grim laughingstock. If it’s darkest before the dawn, 1994 represented those five or ten minutes ahead of the time listed for sunrise. It was no longer pitch black outside. You could begin to see clearly now.

Had there been no strike and the Mets maintained their .487 winning percentage — sixth-best in the entire National League — that would have been good for 79 wins, a gain of twenty from 1993, not to mention a couple of lucky bounces from being a winning team one year removed from being the butt of David Letterman’s monologue. Had they reverted to the low expectations 1993 wrought, they were still highly unlikely to lose as many as 90 games. The Daily News ran a computerized simulation of the daily standings during the strike in lieu of the real thing. According to Bill Konigsberg and Pursue the Pennant, the 1994 Mets “would” have gone 73-89. Not great, but a legit hop, skip and/or jump from the 59-103 that weighed us down in ’93.

I keep coming back to 1993 even as I praise 1994 for getting us away from it. Perhaps I was prone more than I realized to a condition we’ll label Marlin Envy. Yeech, I know, but Florida was a fresh new team in 1993. Colorado, too. I’d never experienced National League expansion from the ground up. Ballparks you hadn’t seen before. Logos you hadn’t seen before. Names from out of nowhere that lodged themselves onto the schedule and into your consciousness. Teal! Purple! The novelty was bracing. What was less delightful was being the one established unit in the senior circuit incapable of taking advantage of the neophytes. We finished behind the Marlins in 1993. We finished behind the Rockies in 1993. We finished behind everybody in 1993.

If you can’t beat ’em, sort of replicate ’em. The 1994 Mets came off a bit like a modern expansion outfit themselves. Not in line with the 1962 version of themselves, but the way expansion teams were constructed in the ’90s, with a handful of high-priced players mixed in with the prevailing gumbo of discards and kids getting a chance they might not have arisen had these extra jobs not been open. The team charter flew by the seat of its pants. Opening Day was April 4. Our Opening Day first baseman, David Segui, was acquired on March 27. Our Opening Day shortstop, Jose Vizcaino, joined the organization on March 30. The first week of the season included the Met debuts of seven other players guaranteed to set few fans’ hearts aflutter. Unheralded rookies Fernando Viña and Kelly Stinnett. Downswing retreads Pete Smith and John Cangelosi. Scrap heapsters Jonathan Hurst, Doug Linton and Luis Rivera. Yet with these and the rest of the Mets off and running to a start of 4-1, who gave a damn about their non-reputation? If we knew the term “replacement level,” we would have embraced it. All we wanted was to replace the bitter taste of 1993.

Of the 37 players who wore the Miracle Mets 25th anniversary sleeve patch in 1994 (you don’t have to be a uniform sleuth to pick out ’94 highlights), only four — Dwight Gooden, Kevin McReynolds, John Franco and Todd Hundley — had previously played for a Mets team that had posted a winning record, something no Mets team had done since 1990. If we were moving on from 1993, we were also inextricably separated from the suddenly not so recent golden age of Mets baseball. Gooden was the last 1986er extant on the roster. 1988’s near-MVP McReynolds returned after a two-year absence, Kansas City offloading him on us so we could dump Vince Coleman on them. K-Mac wouldn’t be back after 1994. and Doc, testing positive like it was 1987, wouldn’t last until the strike. When the 1969 Mets were introduced at a distressingly empty Shea Stadium on July 24 (nothing personal, fellas — Mets attendance landed near the bottom of the NL), they were the only world champions in sight.

Of the 37 players who wore the Miracle Mets 25th anniversary sleeve patch in 1994 (you don’t have to be a uniform sleuth to pick out ’94 highlights), only four — Dwight Gooden, Kevin McReynolds, John Franco and Todd Hundley — had previously played for a Mets team that had posted a winning record, something no Mets team had done since 1990. If we were moving on from 1993, we were also inextricably separated from the suddenly not so recent golden age of Mets baseball. Gooden was the last 1986er extant on the roster. 1988’s near-MVP McReynolds returned after a two-year absence, Kansas City offloading him on us so we could dump Vince Coleman on them. K-Mac wouldn’t be back after 1994. and Doc, testing positive like it was 1987, wouldn’t last until the strike. When the 1969 Mets were introduced at a distressingly empty Shea Stadium on July 24 (nothing personal, fellas — Mets attendance landed near the bottom of the NL), they were the only world champions in sight.

Maybe the most compelling evidence that time was marching on came from the box score of April 5, the season’s second game. Dallas Green, in what was supposed to be his first full season of getting the Mets back on their feet, used a dozen players to beat the Cubs that afternoon. None of the twelve was alive on April 11, 1962, the official date of birth for Casey Stengel’s baby Mets. Our actual expansion roots, just like our glory days, were also growing more and more distant.

In a way, the 1994 Mets, commemorative patch notwithstanding, were, for better or worse, unmoored from their past. It was probably a necessary detachment. The Mets’ past was no longer providing a useful template for their immediate future. Their nascent present was about to evaporate on August 11, anyway. Nineteen players who were Mets in 1994 wouldn’t be Mets in 1995. Some of that was the attrition of a long strike, some of it a fact of replacement level life. For those of us just learning to communicate via computer, the phrase “reboot” was entering our lexicon. Perhaps that’s what we were experiencing as Mets fans back then. Our screen froze in 1993. Somebody must have told us to unplug, then plug back in and see if it works.

Son of a gun, it did. But maybe someone from IT needed to come by and take a closer look to figure out what exactly was going on.

21. 1995

Had the power rankings contrivance existed in 1995, the Mets might have crept to the fringe of the middle of the pack by the end of the season, decently above the cellar-dwelling rabble, far beneath your momentum-laden outfits like the Refuse to Lose Mariners and your eventual World Series combatants Atlanta and Cleveland. But that was no way to measure what we who were paying attention to our Amazins had goin’ on. Comparing the Mets to the powerhouses of the day wouldn’t have reflected the velocity with which our mood had risen. Had we worn mood rings, you would have seen ours turning violet, the color indicating the ring in question wraps around the finger of a person feeling very happy.

Mood rings weren’t undergoing a renaissance in the early fall of 1995, but the Mets sure were, a stark reversal from where they started in baseball’s late spring. The all-encompassing strike that knocked out everything the previous August through October crossed the line from one year to the next as 1994 became 1995. We didn’t know when our game would be played again, and we didn’t know who would play it. The owners, unable to pierce the resolve of the Players Association, hatched a scheme to hire replacement players. Not replacement level players (the Mets had already tried that in ’94), but minor leaguers not subject to union rules; stray retirees who thought they had something left; and, essentially, some dudes off the street. If you put them in major league uniforms and told the fans that these fellas were now your favorite players, maybe it fool some of the people some of the time.

Mood rings weren’t undergoing a renaissance in the early fall of 1995, but the Mets sure were, a stark reversal from where they started in baseball’s late spring. The all-encompassing strike that knocked out everything the previous August through October crossed the line from one year to the next as 1994 became 1995. We didn’t know when our game would be played again, and we didn’t know who would play it. The owners, unable to pierce the resolve of the Players Association, hatched a scheme to hire replacement players. Not replacement level players (the Mets had already tried that in ’94), but minor leaguers not subject to union rules; stray retirees who thought they had something left; and, essentially, some dudes off the street. If you put them in major league uniforms and told the fans that these fellas were now your favorite players, maybe it fool some of the people some of the time.

Thanks to a U.S. District Court judge named Sonia Sotomayor, we never discovered just how gullible we might be. Sotomayor issued an injunction against the owners on the eve of Fauxpening Day, keeping them from unilaterally subverting the collective bargaining tenets that had been in place before the strike. In short, play ball!

Alas, the Mets weren’t prepared to do so, or at least not do it well. On April 26, after an abbreviated Spring Training, they lost their first game, the first game ever played at Coors Field in Denver. On April 27, they lost the second game ever played at Coors Field in Denver. For the first time since 1965, the Mets were 0-2. Two home wins followed (disgruntled fans tossed money at the players in the Shea Opener), boosting the 1995 Mets to .500 for the first and last time.

The season would be shortened to 144 games in deference to the late start. Yet the season started getting long real soon. That’ll happen when your team drifts from .500. For a spell, it wasn’t bothersome. Just having baseball back was a thrill, as it is every April. That never lasts, though. Any baseball might beat no baseball, but bad baseball drops out of contention quickly enough.

For the fifth consecutive season, the Mets were wearing home jerseys that didn’t look quite like the jerseys they wore the year before, their search for an identity taking a sartorial twist. In 1991, they’d added buttons to their racing stripe tops. In 1992, there was an “S” patch to honor the late Bill Shea. The 1993 strategy deleted those ’80s side stripes and birthed the wordmark tail nobody asked for; it was still there in 1994, as were, for just that year, MLB’s 125th Anniversary logo on one sleeve and a quarter-century commemorative emblem for the 1969 Mets on the other. In 1995, the Mets’ motif was back to basics…maybe a little too basic. The tail was off the “Mets,” which was a good deletion, and the overall look echoed what you might call the classic motif of 1965 to 1977. Mets in script, number on the front, no muss, no fuss, not bad.

Except there was something about that script “Mets” that struck this viewer as a little too thin, definitely not as hearty as it used to be. It seemed to speak for what the 1995 Mets — who we weren’t even sure were going to be the 1995 Mets when replacement players roamed St. Lucie — thought of themselves.

We don’t want to bother anybody.

We don’t want to get in the way.

Maybe you’ll come out and join us at the ballpark.

Maybe you won’t.

You might not know who all of us are yet, but that’s OK.

Just look for the familiar name on the front.

Whatever you want to do is fine with us.

We still have a hundred-something games left.

We’ll be here even if you’re not.

A fan will see what a fan sees. For quite a while in 1995, I saw an invisible team. When the Mets did appear in a highlight, it was as backdrop for some other team’s development. The Rockies’ new ballpark. Cliff Floyd of the Expos badly banging up his wrist in a first base collision with Todd Hundley. Chipper Jones of the Braves belting his first career home run into the sparsely populated right field Loge seats at Shea. There was minimal carryover from whatever infused with 1994 with hope before the strike. My main Met coming into the season, Rico Brogna, had won me over as a rookie the summer before when he emerged from what seemed like nowhere to bat .351 in 39 games. I waited out the labor-management machinations without rancor because I knew Rico Brogna was waiting on the other side. In the chill of Denver on Opening Night, Rico batted third and blasted the first home run in Coors Field history in the fourth. The Mets lost in fourteen. Rico’s start sizzled like it had in ’94, then cooled off to solid if not spectacular, which describes the injury-abbreviated career that awaited him. I sort of believed he’d keep hitting .351, just as I definitely believed the Mets who finished just shy of .500 in 1994 would storm past the respectability barrier after Judge Sotomayor gaveled some common sense into the National Pastime.

Solid if not spectacular would have been fantastic for the 1995 Mets at mid-season. The All-Star break came 69 games in, a function of the shortened season. The Mets were buried at 25-44, the third-worst record in all of baseball. Our only All-Star was Bobby Bonilla, whose persona had ventured into elder statesman territory, except for that May Saturday in Philadelphia when he a) ran through third base coach Mike Cubbage’s stop sign, b) got thrown out at third to kill a Met rally, and c) insisted to reporters that Cubbage “can kiss my ass” once told mild-mannered Mike’s side of the story (“I held him up”). Otherwise, Bonilla was being productive at the plate and less destructive than in past seasons to the club’s esprit de corps. Four years into his five-year contract, that’s really all you could ask of Bobby Bo. Still, you prefer to beam with pride rather than grimace in resignation when the lone player representing your cause in a going-nowhere year is introduced at the All-Star Game.

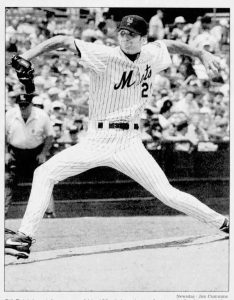

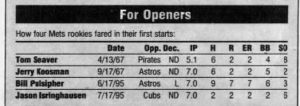

Two genuine spritzes of excitement, delivered a month apart, did burst forth from the rotating lawn sprinkler of player transactions. We didn’t even mind if our trouser legs got soaked as we strolled down the street when the news hit us. On June 17, Bill Pulsipher, 21, was summoned to make his major league debut. Pulsipher — Pulse — was the lefty starter we’d been hearing about since the year before when he was dominating Double-A. On July 17, Jason Isringhausen, 22, got the call to throw his first pitches in the bigs. Isringhausen — Izzy — was Pulse’s righty complement and the object of a swelling fan outcry to get him up here already from Norfolk, where he’d been toying with Triple-A batters. Each pitcher went seven innings in his respective introduction. Pulse’s, at Shea, were messy and the Mets lost (I witnessed it in person alongside this Jason guy I knew only from an AOL board; how exotic!). Izzy’s, at Wrigley, sparkled and the Mets won (I listened to most of it on the radio because something called The Baseball Network couldn’t be bothered to beam it into New York). For fourteen combined innings, our mood rings escaped black. For fourteen combined innings, the kids allowed us to anticipate what might be.

What actually was by the drizzly Sunday morning of August 6 had reverted to dreary, as the New York Mets sported the worst record in the National League, 35-57. The trade deadline motivated them to send Bobby Bo to Baltimore and Bret Saberhagen to Colorado. In a couple of weeks, they’d end the Brett Butler experiment and dispatch their leadoff hitter back to Los Angeles from whence he came. Izzy and Pulse were the bleeding edge of a de facto youth movement. The Mets didn’t explicitly advertise their change in direction. Nobody implored us to bring our kids to see their kids, “their” kids dressed in those not quite satisfying thin-scripted jerseys, yet that’s what I was doing on August 6. Well, no kiddies, but I did bring my wife, both of us in box seats alongside my college friend Rob Costa, by 1995 a sales rep in good standing for what would eventually be reviled as Big Pharma. Rob was a sweetheart who didn’t much care about baseball, but tickets to Mets games were one of the perks he was authorized to disperse at his discretion. He made us his clients for the afternoon.

I’d been to six games since the strike ended. The Mets were 0-6 when I appeared in their midst. On August 6, there was mist, but there was also no mistaking that a losing streak was about to be broken. Third-year starter Bobby Jones gave up a first-inning run to the Marlins when Terry Pendleton grounded out to second with a runner on third and less than two out. Pendleton was a ghost of Shea pennant race past. Gloomy as the skies were, this was no day for ghosts or, for that matter, the past. Jones settled in to keep the Fish at bay through six. In the meantime, Bobby from Fresno drove in the tying run on a squeeze bunt in the second; my main Met Rico went deep to provide us a lead in the fifth; erstwhile utility infielder Edgardo Alfonzo, lately getting a chance to wrangle third base with Bonilla no longer around, chipped in an RBI in the sixth; and Jeff Kent, who never seemed to shake the boos his crummy first two months brought on, put things out of reach with a three-run homer. Jones pitched into the seventh of a 7-3 Met victory, my first since May 1, 1994.

Jones was 25, same age as Brogna. Alfonzo, or “Fonzie,” was all of 21. Kent was the senior youth at 27. Throw in Pulse, Izzy, 26-year-old Hundley behind the plate most days, 24-year-old Carl Everett around in right, maybe 25-year-old left fielder Damon Buford, who we got for Bonilla…did we have something here? Minor league slugger Butch Huskey would be promoted a couple of weeks later. He was 23. The other Oriole we received as payment for Bobby Bo, Alex Ochoa, would be up in September. “Five-tool” was the scouting report attached to this intriguing 23-year-old.

We had something here, all right. We had a young Mets team finding its footing all at once. From that gray Sunday afternoon at Shea in the company of Rob Costa forward, all the way to the end of the season, the Mets played 52 games and won 34 of them, an eight-week pace three games better than anybody else in the National League over that span and, for what it was worth, one game better than the 1986 Mets (33-19) from when they played their final 52 regular-season games. Meanwhile, Saberhagen and Butler were helping the teams to whom they’d been traded to the expanded playoffs, the same tournament that would include Worst Team Money Could Buy alumni Eddie Murray with the Tribe and Vince Coleman with the M’s. Bonilla didn’t show Baltimore October, but he won terrific-teammate kudos for pushing modest Cal Ripken from the dugout to take a victory lap at Camden Yards when Cal surpassed Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games played standard on September 6.

What was that acronym I learned from America Online? “LOL,” which by the 2010s would often be something done in the Mets’ faces when players they moved on from moved on themselves to bigger things and better situations. Yet we didn’t miss any of those veterans who wore out their Shea welcomes. We had the kids, and this old man of then 32 was bringing himself as often as possible to see them in winning action. My 0-6 start became a 7-7 final personal record, a crisp .500 in my steno pad of dutifully logged results, secured on the last day of the season when nothing could have deterred my rushing to Flushing. It took eleven innings, but the Mets beat the Braves for a series sweep. They had just swept the Reds the series prior. In August, they had swept the Dodgers, Izzy outpitching reigning rookie phenom Hideo Nomo in a sunny Sunday finale. The Braves, Reds and Dodgers were the three National League division winners in 1995. DiamondVision let us know the Mets were the only NL team to take three of three from all three flag-bearers. We were creeping into the highlights on our own merit.

The Mets’ final record in that 144-game season was 69-75. Momentum might have carried them to 81 or more wins had the pocket schedule contained its usual allotment of boxes. The upsurge was enough to catapult the Mets from fifth/last place in the East to a tie for (admittedly distant) second. We were statistically better than Florida, better than Montreal and no worse than Philadelphia, the league’s most recent pennant-winner. Give us time and we could think about taking aim at Atlanta.

I’ve rarely ended a Met year in a better mood, even if there was no ring to prove it.

Great summary as always. I have one of those non-existent World Series balls too. How can 1994 be 30 years ago?

And, BTW, how can 1986 be 38 years ago?

1995 was the year I paid the least attention to the Mets, ever. I was still livid about the strike. I went to Opening Day because someone gave me tickets, but I didn’t care. I was so angry I stopped paying attention to sports, period. I think I read Lupica’s DN columns and otherwise ignored the sports section.

96 and 97 are foggy memories. I know we had Bernard Gilkey at some point, and some guy called Lance had 200 hits, but I was a casual non-observer. I really didn’t start paying attention until ’98 and was finally all-in with the arrival of Mr. Piazza.