KVELL: To beam with pride and pleasure

KVETCH: To complain

—From “Selected Yiddish Words and Phrases,” courtesy of some considerate landsmen in Santa Barbara, Calif.

A Mets fan generally finds himself kvetching or kvelling. It’s tempting to kvetch about the sleepy offseason that followed the signing of Michael Cuddyer or the way the Mets apparently charge their youngsters to “voluntarily” work out under their indirect auspices so they can someday become Mets who can afford the prices the Mets charge (though if they don’t volunteer, then they must not really want to be Mets, eh?). I can kvetch another day as needed. It remains a long winter.

Today I choose to kvell.

I’m actually choosing to kvell about a week ago today. The statute of limitations hasn’t run out on beaming with pride and pleasure over an event from seven days ago, has it? I can remember when the Mets have won big that, as the next season approached, there was an implicit tendency to “get over it” quickly or “put it behind us” by spring because, well, there was another season to play and you couldn’t rest on your laurels. You had to go out and win again.

The Mets, you might have noticed, didn’t go out and win again whenever they won big. Nor have they won big in quite a while. When you’re short on big wins, there is solace to be taken in the victories of long ago. They teach us something we can use going forward (as opposed to going backward). Or they just mercifully distract us from going nowhere. It’s never too late to retrokvell. That’s what the big wins are for.

So to kvell with it. I’m going to kvell a little more about Ed Charles from last week at the Queens Baseball Convention. That was a big win for all involved.

I have a confession to make about Ed Charles’s playing career. I don’t remember any of it firsthand, not even its late pinnacle. I remember clearly what his final team did and I know he was there when they did it. That fall is the foundation for all my fandom that’s since followed. I just didn’t know anything about him at the time they were doing it. (Yes, I feel sort of guilty about having once been a small child.) Despite my plunging into a lifetime of Mets love in 1969, there’s a cache of 1969 Mets whose contributions I had to catch up on after the fact.

Don Cardwell.

J.C. Martin.

Jack DiLauro.

Bobby Pfeil.

Rod Gaspar.

Ed Charles.

What they all had in common was they were either gone or going by 1970, my first full year as a full-fledged Mets fan. 1970 reinforced 1969. 1969 was the welcoming gift that said you can win like this every year. 1970 was the fine print that mumbled you probably won’t win like that ever again. But 1970 was quite fine by me, actually. Baseball from April onward, maybe we’d win, maybe we wouldn’t, but no doubt it was there everyday. At six, in 1969, I was enthralled. At seven, in 1970, I was engaged. In between, on October 24, 1969, the Mets released Ed Charles. The story was they had to make room on their roster to protect younger players…and he wanted to retire anyway…and they were going to give him a job in their promotions department…which didn’t exactly materialize as planned.

At eight, in 1971, I bought a book that listed everybody who played for the Mets in 1969, not just the stalwarts of ’70, but those whose presence predated or averted my consciousness. It was in the statistical appendix to The Perfect Game: Tom Seaver and the Mets by Tom Seaver with Dick Schaap (which is to say by Dick Schaap) that I first encountered Ed Charles. He was, at initial glance, no more than a name, a strange name among the Swobodas and Joneses and Gentrys and so forth, the Mets who stuck around to make a direct impression on me. This Charles was a Met only in the sense that Tom Seaver’s book said he was.

I had to take it on faith that Ed was as important as anybody else to the so-called Miracle Mets. I had to understand that the man who was first to join Jerrys Koosman and Grote on the mound at the end of Game Five was scurrying on merit. I had to believe Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson whenever they’d bring him up approvingly between pitches. The Glider Ed Charles; the Poet Laureate of the 1969 Mets Ed Charles; the Elder Statesman of the World Champion Mets Ed Charles. He had more titles than the Mets do to this day. He had enough titles to qualify as English nobility.

With more seasoning, I came to comprehend that the Mets I hadn’t known were Mets, too, that they ran and they threw and they fielded and they hit and they hit with power on occasion. I embraced, despite the sense one develops at an early age that the universe couldn’t have possibly existed prior to one’s awareness of it, the concept of there having been Life Before I Came Along. I got that the 1969 Mets were a team like no other, not only for their easily embroidered accomplishments, but for their whole overwhelming the sum of their parts — just as together they overwhelmed Chicago, Atlanta and Baltimore while I was first getting to know them. I read more and I listened more and I looked at the pictures and I watched the film and the videotape and I took it all in as best I could no matter than I wasn’t able to take it in as it happened.

You might say I’d been trying to catch up with Ed Charles ever since I first saw his name listed among everybody who played for the Mets in 1969. You might also say that on Saturday, January 10, 2015, at the Queens Baseball Convention, I finally pulled even.

QBC wasn’t my first encounter with Ed. In 2009, we met in Caesars Club, he a de facto Mets ambassador, me a diehard Mets fan. It was Opening Day. Not the first game at Citi Field, but Opening Day in Cincinnati. A friend affiliated with a sponsor that was hosting a party did me a solid and put me on a list. The same sponsor brought in Charles, Ed Kranepool and Mookie Wilson to sign autographs and be legends. I was suitably impressed (so impressed that I couldn’t bring myself to talk to the Krane). I’m not an autograph hound, so at first I didn’t join the lines that I saw developing for the players. Then, when the queues shortened, I figured why not, and waited to meet the Glider.

The exchange was brief. I told the man I wanted to thank him for all he did for the Mets, for being such a great Met when he played. I didn’t want to say “you were my favorite player” or “I remember the time you…” because he wasn’t and I didn’t. I veer to the literal. Ed said, in so many words, all right, thank you very much. (I said more or less the same thing to Mookie and received more or less the same slightly baffled “so you don’t want an autograph?” look.)

I was quite satisfied with the interaction. He was Ed Charles, 1969 Met, whether I had directly experienced his playing or not. When he discussed and read his poetry at the Mets’ 50th-anniversary conference at Hofstra in 2012, I eagerly listened from the audience but I didn’t need to seek him out. I’d already done it. I was like the cop in the Kids In The Hall sketch who comes back from his European vacation and shows his partner a lone photograph.

“Ya just got the one picture?”

“I took another one, but it didn’t turn out.”

One hello. One view from the back of a college auditorium. Plus the various Old Timers Days and commemorative gatherings and whatever I caught on TV and whatever I kept reading and the dramatization of young Ed Charles in the 2013 movie 42, the highly idealized Jackie Robinson biopic that conveys the spirit of an essential American story even if it takes its sweet liberties with some of the details. As soon as I saw the scene in which a little kid named Ed goes to a Spring Training game and roots his heart out for Jackie, I knew who he’d grow up to be. And for anybody who hadn’t devoted a lifetime to reading about a certain whole and all its parts, the director included this helpful postscript graphic regarding the wonderfully earnest kid from that scene:

Ed Charles grew up to become a Major League Baseball player. He won the World Series with the 1969 Miracle Mets.

They took no liberties with those facts. I knew they were true.

The Queens Baseball Convention was founded to fill a void the Mets themselves probably don’t realize exists. Mets fans want to be together when there’s no baseball, want to talk Mets baseball no matter the month, want to hear about Mets baseball all throughout the year. The people who put QBC together — primarily (though by no means exclusively) Shannon Shark, Keith Blacknick and Dan Twohig from Mets Police — made not just filling but obliterating the void their mission. But there was a sub-mission as well.

Let’s do something for Gil Hodges.

Let’s do something for the memory of Gil Hodges.

Let’s do more than not forget the manager of whom every one of his contemporaries spoke and continues to speak so highly.

Let’s make a point of remembering him and talking about him and emphasizing what No. 14 was all about for any Mets fan who wasn’t certain why we keep talking about him.

That goal resulted in the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award. It was established a year ago when Gil’s son was gracious enough to tell us the idea was OK by him and was thoughtful enough to attend the first QBC to accept the award on behalf of his father. He even brought Art Shamsky. When we did it once, it became real. When it became real, we had to do it again.

We had to choose another recipient. Ed Charles was the first and only name considered. All that had to be done was to let him know he was chosen and ask him to come and accept.

Which, in my role as consulting historian to QBC (a title I made up for myself), it fell to me to do.

Which amounted to e-mailing somebody who I believed had Ed’s contact information, but didn’t.

Which led to e-mailing somebody else who I was told had Ed’s contact information.

Which led to calling that person to get Ed’s contact information.

Which led to being given Ed’s phone number and being told I could go ahead and call him.

Which led to me calling a 1969 World Champion New York Met…at home.

Which led to me putting it off for too many days on top of how long it took me to secure his phone number because as soon as somebody said to me, “Here’s Ed Charles’s number,” I froze. At that instant, I was nobody’s consulting historian. I was instead six and overcome by awe for the idea that I could call somebody on the Mets. Never mind that he hadn’t been on the Mets in 45 years. Never mind that this was a professional obligation. Never mind that in my working life I’ve called thousands of people who had no idea who I was to ask them questions.

In the moment of staring at Ed Charles’s phone number, I was six years old. Every Met was a movie star, an astronaut and a Met and I would never dream I could just pick up a phone and talk to somebody of that ilk. When I was six and missed school, my mother would insist I call another kid in my class to find out if there was homework. I hesitated to do that. I figured the other kid would hang up on me or tell me to go away. I still half-expect that reaction when I call people today. Hooray for the advent of e-mail, y’know? Except Ed Charles didn’t have an e-mail address. He had a phone number. If this Gil Hodges award was going to gain the traction we hoped it would, I had to use it.

So I did. I called Ed Charles. At home.

He didn’t hang up on me or tell me to go away, which I considered a preliminary victory. Someone you’ve never heard of calls you out of the blue to tell you you won an award you’ve never heard of and would you mind dropping by this event you’ve never heard of to pick it up and — if you’re up for it — maybe say a few words, you’d consider ending the conversation before it got much further.

But Ed Charles didn’t do that. He listened to my spiel, he checked his calendar, he asked for a little more information and he gave me his home address so I could send it through the mail.

Now I had Ed Charles’s phone number and address. Me, a former six-year-old. I suppose this says something good about the way things begin to tumble into place, but I also can’t shake the feeling that something’s a little awry with a world that grants me that kind of entrée to a 1969 World Champion New York Met.

I know I’m no kid. I know I’ve written books and articles and blog posts galore. I know I’ve interviewed plenty of people reasonably famous in their fields, in and out of baseball.

Still, c’mon. It’s me. What am I doing with a 1969 Met’s phone number and address?

Nevertheless, I followed through. I wrote Ed Charles a letter in which I explained the Queens Baseball Convention, the Gil Hodges award and why we wanted to present it to him. I slipped in something about having been six years old in 1969, because a former baseball player has probably never heard an adult invoke his childhood fandom before. Then, the following week, I called him to make sure he received it.

He had. He was good with it. He said he’d be there. That, I said, is wonderful. I told him I’d check back in with him shortly before the QBC to firm up all details.

When I did, let’s just say I got the impression that receiving the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award at the Queens Baseball Convention wasn’t uppermost in Ed Charles’s thoughts. Thus, despite his calm assurance that he would join us, I became convinced he wouldn’t. That he’d forget. That he’d take ill. That it would be too cold. That it would snow. That I had dropped the ball in making certain he found his way there. As late as 5:30 last Saturday, I could hear myself making the lamest of “though our guest of honor couldn’t be here today…” remarks and disappointing everybody who had been waiting for and maybe come only because of Ed Charles.

Then, while participating in a panel nobody would remember I was on because all anybody would remember was that I said Ed Charles was coming and he didn’t, I got the high sign from my wife who had been kindly keeping an eye on the door. Ed Charles had arrived.

I excused myself and bore witness to the entry into the Queens Baseball Convention of Edwin Douglas Charles. The Glider. The Poet Laureate of the 1969 Mets. The Elder Statesman of the World Champion Mets.

Ed Charles was here, resplendent. Everything about him was world championship. The black cane. The silver suit. The tan topcoat that complemented the suit beautifully. The topcoat got my attention in particular because a friend once recalled for me the scene at Shea Stadium on the day in 1970 when the 1969 flag was raised. Ed had been relegated to ex-Metdom before any of his teammates were, which could have put a damper on the festivities the way getting over it and putting it behind us can.

But the residue of miraculous machinations hadn’t evaporated from Shea yet.

“Ed was…back for Opening Day. We in the stands had no idea he was there and thus, as the Mets were getting their world championship rings, we suddenly heard the name Ed Charles announced over the P.A. system and saw him running out of the dugout, wearing an open trench coat, waving both arms high to the fans as he went to get his ring. All the players along the first base line applauded him and I think he got the longest ovation of all the players.”

From wearing a trench coat when the other World Champion Mets were in uniform to wearing a topcoat when so many of the fans at McFadden’s were wearing Mets jerseys. By any outerwear, it was Ed Charles.

Ed Charles, who was portrayed in a major motion picture.

Ed Charles, who rode in the Canyon of Heroes.

Ed Charles, who tossed off light verse on the team bus and recited sacred poetry in Bryant Park.

Ed Charles, who after playing professional baseball for most of 18 years, earned a World Series ring in his very last game.

Ed Charles, whom I was almost too scared to call but did anyway and now he was at QBC and he was looking for me.

There’s a word for when Ed Charles shows up like that.

Amazin’!

Logistics ensued. Shannon cut short the last panel of the day. Keith and Dan transformed a humble stage into a worthy podium. Ed asked where I wanted him, as if being right here right now and having been at third against southpaws hadn’t sufficed. I didn’t want to put him out in any way, so I offered him his choice. Sit in the front row alongside Steve Jacobson — the longtime Newsday columnist who showed up specifically to support Ed, one of his very favorite players to cover — and come up to accept the award when introduced; or sit on the chair Keith placed on the podium until it’s time to get up and say a few words if, in fact, you wish to say a few words. I was cognizant of the black cane and wanted to be fully attuned to whatever condition that necessitated it.

It’s none of my business how old anybody is, but baseball’s funny about openly sharing vital statistics. For example, the January 2015 page of the official Mets calendar over my desk tells me, even though I didn’t ask, that Daniel Murphy is 6’ 1”, 215 lbs. and will be 30 years old this April. It’s that sort of openness with data that made it easy for me to know that in the same month Murph blows out his candles, Ed is slated to blow out just as many…plus 52 more. I wasn’t about to make a nearly 82-year-old man stand up any longer than he deemed necessary.

You know what Ed chose to do? He chose to stand for the entire duration of the presentation and everything after, which probably added up to almost an hour. He deemed it necessary. He stood while I spoke from a prepared text. He stood while he spoke without notes. He stood while he asked for audience questions. He stood while he answered them. He stood while he read from a revised version of “An Athlete’s Prayer,” the very same poem he read in Bryant Park after he rode in the Canyon of Heroes — references to DiMaggio and Clemente substituting for those hailing Ruth and Cobb, though “Robinson” stayed a staple of both. He stood while the audience stood and applauded. He stood while Mets fans streamed toward him afterwards for, basically, the same reason I went over to him in Caesars Club six years ago: for being such a great Met when he played, though maybe to add “you were my favorite player” or “I remember the time you…”

I can do that, too, now, because I have revised memories of Ed Charles. I remember the time he came to QBC and (all apologies to survivors of the Art Howe administration) lit up the room. I remember the way he knew exactly what to say on the occasion we honored not just him but his manager. I remember that he warmly tailored his remarks to be as much about Gil Hodges as they were about Ed Charles. I remember thinking that he’s no doubt given some iteration of this talk at countless Hot Stove gatherings, but today, in 2015, it felt fresh and new and alive and the embodiment of what a friend who was there called living history. In “An Athlete’s Prayer,” there’s a line Ed wrote that says, simply, “We players perform as best we can.”

Funny, he should say that. As I stood off to the side of the podium after delivering my introduction and kvelled from watching Ed do his thing, the word “performance” came to mind, specifically in the context of a soundbite constant MLB Network viewers might recognize. It’s one you might have heard broadcast in Howard Cosell’s voice, the singular ABC announcer (and original Met pregame radio host) booming, “WHAT A PERFORMANCE!” Humble Howard exclaimed it after George Brett hit the third of three home runs in one Royals playoff game.

Brett played third base for Kansas City (as did Charles, for the post-Philadelphia, pre-Oakland A’s prior to his being traded to the Mets). Brett’s three home runs in Game Three of the 1978 American League Championship Series off Catfish Hunter — future Hall of Famer versus future Hall of Famer — indeed represented a performance worthy of Cosellian exultation.

But this, from Ed Charles, for every Mets fan on hand…this was a performance for the ages.

Oh, and I remember the ring. I’ve never been about the rings (baby), but I gotta tell ya that as I continued to stand and kvell, I caught sight of Ed’s ring…his 1969 World Series ring, that is. I’d seen pictures of the ’69 model, so it was familiar to me, sort of like when I first entered Fenway Park — the first non-Shea ballpark I ever visited — and recognized it because I’d seen it on television. I’d seen one of those rings displayed in Cooperstown, behind glass. I’m pretty sure there’s one in the Mets Museum, too. But at this moment, I was seeing a 1969 World Series ring on a 1969 World Champion Met. A 1969 World Champion Met who talking about 1969 and Gil Hodges to a group of ardent Mets fans because I called him and asked him to and he got a ride regardless of any ball I feared I dropped and because this isn’t the kind of man to not come through with a performance for the ages where there is a critical mass of ardent Mets fans looking forward to seeing him.

Like I said, I’ve caught up with Ed Charles. Now, I’d like to think, we are forever tied.

Also, I may need to revise my All-Time Favorite Mets list.

You can listen to the entire Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award presentation from QBC 2015 here, courtesy of Alternative Sports Talk Radio.

Below is the text of my introduction of Mr. Charles. Embedded audio is posted beneath it.

***

Last year at QBC, we inaugurated the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award in memory of our late world champion manager — and might I add Hall of Fame human being — to honor those Mets who, when we think of them, will always warm our hearts, brighten our spirits and light our way. We dedicated the first award to Gil himself and were thrilled to present it to his son, Gil, Jr., who sends us his best regards. He really wanted to be here with us again but can’t be. He promises us he’ll join us once more at QBC next year.

For our second year, we are just as thrilled to be able to present it to Ed Charles, New York Met third baseman, 1967 to 1969, world champion forever.

Selecting Ed was not a hard call. His leadership as a player mirrored Gil’s as a manager. The esteem he’s held in sits at that same high level. Every mention I find of Ed since he stopped playing baseball usually goes the like this:

“Ed Charles is one of the nicest people I ever met.”

There’s usually something about a small exchange with you that meant the world to your fans, whether it was from when you were playing or from when you were retired from the game. You sent letters and poems and offered a handshake and a smile and never stopped letting Mets fans remind you how much THAT meant to them and how much 1969 continues to mean to them.

It occurs to me that because your playing career ended with the World Series that you’ve been a quote-unquote “1969 Met” longer than any of your teammates. You were out there carrying the banner on your own until the other guys on the team eventually joined you in retirement. And you’ve done it with a keen awareness of what it means to Mets fans and world-class empathy that’s rare these days.

It’s no small thing, and we appreciate you no end for that.

If you’re keeping score at home, as Bob Murphy liked to say, Ed was the first 1969 Met in professional baseball. He started playing in 1952, approximately six years after that scene in the movie 42 where a young Ed Charles catches the eye of the great Jackie Robinson, who is on his way to eventually joining the Brooklyn Dodgers and changing America for the better.

If I’ve read the background correctly, Ed, in real life, Jackie waved to you as his train was pulling away. In the movie he throws you a ball. I guess that version is more dramatic, but either way, the inspiration was just as real.

Ed is one of two 1969 Mets to begin his major league career the very first day the Mets themselves came into existence; Ed and Ron Taylor each played their first big league game on April 11, 1962. Ron was playing for Cleveland, Ed for the Kansas City A’s.

If you’ve done the math and noticed it took Ed ten years to make the majors after starting in the minors, just realize how much perseverance that required and what a world he was trying to succeed in, one where most ballclubs stuck to a quota system when it came to African-American players. Ed EARNED a much earlier promotion. That he didn’t get it didn’t stop him from making it.

As he told Steve Jacobson in the book Carrying Jackie’s Torch, talking about himself and his contemporaries who were routinely discriminated against through the 1950s in the minor leagues, “Jackie integrated the major leagues. We integrated baseball.” And when you read Steve’s book, you learn all over again that there were plenty of places in baseball that didn’t want to be integrated.

Ed, who of course wore No. 5, is one of FIVE third basemen to lead the Mets in home runs in a season, which helps explain Jerry Koosman’s sound advice: “Never throw a slider to the Glider.” The other third basemen in question: Charlie Smith; Howard Johnson; Bobby Bonilla; and the current No. 5 at third base, David Wright. Ed did it in 1968. And we all know what happened the next year.

Regarding home runs: Ed hit 21 in his not quite three seasons as a Met, but SIX of the home runs came off Hall of Famers: Juan Marichal, Don Drysdale, Bob Gibson, Phil Niekro, Gaylord Perry and Steve Carlton. Just so you understand, beyond his demeanor, determination and grace, Ed Charles could play some ball.

The home run against Carlton and the Cardinals was Ed’s most significant. It followed Donn Clendenon’s on September 24, 1969, and gave Gary Gentry an insurmountable lead that allowed the Mets to clinch their first title of any kind in the National League East. I also like that it came off Carlton, who was still pitching against the Mets as late as 1986 — another pretty good season — and threw a game that year against rookie Jamie Moyer, who pitched against Johan Santana and the Mets in 2012, just about a month before Johan threw the first no-hitter in Mets history.

I think it’s appropriate that Ed has that kind of reach across the generations. They called him the elder statesman of the 1969 Mets. How elder? Ohmigod, he was 36. Yes, ancient. But that’s how young the Mets were then, and gets at a larger point: how much those younger Mets looked up to Ed and how much Gil Hodges trusted him to be the on the field, in the clubhouse leader that a championship team needs. It’s no wonder, as George Vecsey wrote in the aftermath of 1969, that “Ed was the most popular man in the Met clubhouse”.

You’ve no doubt heard Ed referred to as the Poet Laureate of the ’69 Mets. I ask you: how many teams have poet laureates? Ed has taken poetry to heart all his adult life and written some very serious and sensitive verse in his time. But this one, a little lighter in tone, I think is my favorite. It’s from the summer of 1969:

East Side, West Side

Word is goin’ round

When late October comes

The Mets will wear the crown

Ed was the oldest player on that team. The youngest? Wayne Garrett, who shared third base with him in yet another of Gil’s beautiful platoons: Ed facing the lefties, Wayne the righties. In a period where there was a lot of talk about a “generation gap,” those guys joined together and contributed to the ultimate team effort.

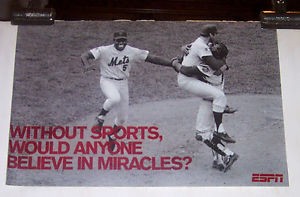

As it happened, in Game Two of the World Series, lefty Dave McNally was pitching for Baltimore, so Ed was the third baseman. He started the winning rally that day and scored the winning run. In Game Five, it was McNally again, so it was Ed at third again. The first 1969 Met to make it to the mound after the last out of the World Series who wasn’t the pitcher or catcher? That was Ed Charles. The picture of Ed charging — not “Gliding” that day — is iconic and perfect. Ed was every Mets fan, every New Yorker that day. About a dozen years ago, ESPN used that photo of Koosman and Grote and Charles in an ad campaign whose point was to celebrate sports.

I don’t know that any group of people celebrated anything like Mets fans celebrated and still celebrate those 1969 Mets. For that, we will always thank Gil Hodges and we will always thank Ed Charles.

Ed Charles was mesmerizing and inspiring, and your introduction set the stage beautifully. It was a wonderful event, and I feel honored to have been there to witness it.

Thank you, Sharon. Thank you for the beautiful pix as well.

Beautifully put, Greg. As Mets fan are so accustomed to kvetching, I didn’t even know kvelling was a thing (and my spellcheck doesn’t either), but you’ve earned a lot of kvelling here. And congrats to the committee who selects the recipients for the award that honors our most honorable figure…Ed Charles is the perfect honoree.

A few summers ago on a miserably hot day, my wife, daughter and I were at the annual feast at Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in Williamsburg, gorging on all sorts of sausage and peppers, zeppoles and whatnot, waiting for one of NY’s most surreal sights, the Dance of the Giglio (80 foot high tower on a platform with about a 20 piece band being carried down the street by 100+ men). When who do I see but Ed Charles, looking quite dapper on a day when everyone else was succumbing to what felt like Death Valley heat with New Orleans humidity…not to mention looking more fit at about 80 than, well, never mind about my physique. I’ve accumulated a pretty cool list of random celebrity sightings over the years, but I almost always leave them alone, and when I pointed Ed out to my wife, was going to leave him alone too. But my wife pointed out that he was wearing a Mets Alumni polo shirt, probably not designed to hide his identity, and probably loves when men of a certain age regale him with stories of their childhoods watching him play. So I did. Being a few years older than you, I remember the Glider just fine. Went up and introduced myself, got a warm smile and handshake, and told him that the picture you have accompanying this article is my favorite baseball photo ever thanks to the pure joy on his face, the joy of reaching what he had probably dreamed of since he was a boy idolizing Jackie Robinson, joy that no one could ever take away from him, ever. He, as you’ve experienced, couldn’t have been more gracious. He wasn’t a guy who put up any eye-popping numbers, the back of his baseball card never made anyone say wow. But in many ways he was as an important player to that team as any of the stars were.

Thank you, Dave — and that must be one blessed street fair to attract such a high caliber of reveler: you, your family, the Glider. Take that, San Gennaro.

I was in the first row during the presentation and you did a wonderful job with your introduction. I was so impressed when he entered the room dressed impeccably. He always was a classy guy.

His talk was inspiring and wished more QBC attendees had stayed. Even though I had a long ride home (MA), I had to see Ed, one of my heroes from 1969.

Thank you for your participation again this year and am looking forward to what you guys are planning for 2016.

Appreciate your coming, your staying and your thoughts, Frank. Whatever we’ve got in the way of remembering Gil next year will be even better if we can do it through the prism of the 2015 world championship.

Greg, thanks for a post that makes the reader feel like he/she was there. I couldn’t make it again to the QBC (my son had travel hockey that day), but I felt I was right there with the all of you plus the Glider, via your essay.

Back in the day (c.2004), before the Internet became the monster it is today, fans still had to line up outside Shea for opening day tickets each January. In 2004, the designated morning registered a frigid 9 degrees. The lines of Met fans eventually snaked indoors, where after purchasing tickets, there was also a meet-and-greet with hot chocolate, donuts, and Mets Alumni, including Ed Charles, 1969 World Series Champion.

Mr. Charles was as gracious and accommodating then as you indicate he was at the QBC ’15. He is a treasure in his own right; thanks again for sharing the story of your interactions with The Glider.

Thanks Will. Hope the hockey schedule is more forgiving next January.

Seemed that “first day tickets on sale” day always lowered the temperature by 30 degrees.

This is beautiful. Thank you, Greg.

Thanks very much, Tad.

I’ve had some discussions with Ed over the past year for a book project and he could not have been more gracious and helpful. His connection to Jackie Robinson — about whom he wrote a beautiful poem — is truly profound, from the childhood encounter to some meetings he had with Jackie later in life. I think Jackie not only inspired Ed to play baseball at a time (the 1950s-early 60’s) when it was still difficult for blacks to make it to the bigs, but also to work with inner-city kids in the Bronx following his retirement from baseball. I couldn’t be happier that the Glider received this award from QBC.

I love that when Ed Charles worked with those kids, he didn’t bother mentioning his affiliation with professional sports. It wasn’t about him, it was about them.

Great job on the recap , Greg. Wish I could have attended, but hopefully next year. And, where else but on FAFIF would u spot the term ” retrokvell” ??

Hope to see ya there, Jack. And if not here, then I ask you — retrokvell where?

[…] Our main man the Glider is the only Old Timer to rate two Diamond Club Girl escorts. He literally skips to the foul line. Are the Diamond Club Girls just that lovely or is Ed Charles just that happy to be here? […]

[…] a more important takeaway to be had from Gil Hodges: A Hall Of Fame Life. There’s a reason we still talk about Gil in reverent terms 43 years after his […]