Ray Daviault first came out of the bullpen for Casey Stengel on April 13, 1962. the second reliever used in the New York Mets’ first-ever home game. Ray’s mere presence made him the first Canadian in a Mets uniform. On July 7, after Marv Throneberry delivered a pinch-hit two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds, Ray had his first win on this or any continent.

Les Rohr was the first player the Mets ever chose in an amateur draft, the second player chosen overall in 1965. On September 19, 1967, he became a big leaguer for the first time, beating the Dodgers at Shea Stadium, 6-3. Les would finish the year with his second win, besting Don Drysdale in Los Angeles come September 30.

Rick Baldwin would have had enough of a challenge reaching the majors at age 21. Assigning him No. 45 could have only added to the pressure. Forty-Five had just been vacated by Tug McGraw, traded in the preceding offseason. Being the first to follow a legend, even numerically, is the definition of a tough act to follow. Yet in his first appearance, on April 10, 1975, Rick threw a scoreless inning of relief and he settled in nicely, pitching in a third of all Mets games that season.

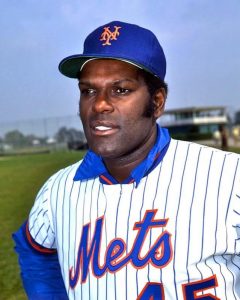

Claudell Washington had no act to follow. He was a trailblazer in his time, his time being 1980 in terms of the Met clock. He was the first acquisition of the Doubleday-Wilpon regime and, through his part in a Magic summer, Claudell indicated the new general manager Frank Cashen knew what he was doing when it came to reeling in talent.

Tony Fernandez was supposed to help make things better in 1993. Honestly, he didn’t, which was too bad, not only for the 1993 Mets, but for a shortstop who had distinguished himself greatly as a Blue Jay and Padre. The Mets would trade Tony to Toronto after a couple of months and Tony would help make things even better for the defending world champions, helping the Jays to their second consecutive Series win. Like Claudell Washington, Tony Fernandez enjoyed a long post-Mets playing career.

Phil Linz’s calling card was a last. It was his off-field playing, of a harmonica, that was credited in legend for spurring the Yankees to the final pennant of their seemingly endless American League dynasty. With Phil tooting away on the mouth harp on the team bus; manager Yogi Berra telling him to, in so many words, put the damn thing away; and Mickey Mantle making sure Phil heard differently (“Yogi says play it louder”), the backup infielder caused the usually mellow Berra to blow his stack. The slumping Yankees suddenly caught fire and Phil Linz was forever a musical icon.

That was in 1964. In 1967, with the Yankee empire too far gone to be saved by a charming anecdote, Phil Linz became a Met. He’d keep company for a season-and-a-half with beloved Mets coach Yogi Berra, the two of them posing happily for photographers once reunited at the Mayor’s Trophy Game. Unsurprisingly, a harmonica was in the picture. The Mets released Linz after the 1968 season, though Gil Hodges invited him to Spring Training for the following year. Phil declined, seeing as how he had thriving nightspot Mr. Laffs to tend to in the city. And besides, as the former New York/New York player put it to author Bill Ryczek decades later, “I was tired of sitting on the bench for a ninth-place team.”

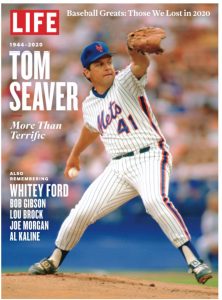

The Mets wouldn’t be a ninth-place team in 1969. Gil Hodges had plenty to do with that. So did his ace pitcher, Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver had a lot to do with everything from 1967 until almost the middle of 1977 and then again in 1983. How completely did Tom dominate the Met scene during his long, if interrupted tenure? Let’s answer that literally. Seaver started 395 games for the New York Mets and completed 171 of them. By comparison, since 1992 — the year Tom Seaver became the first player inducted into the Hall of Fame bearing a Mets cap on his plaque — 148 different pitchers have started 4,528 games for the Mets and together they completed 167 of them.

The Mets wouldn’t be a ninth-place team in 1969. Gil Hodges had plenty to do with that. So did his ace pitcher, Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver had a lot to do with everything from 1967 until almost the middle of 1977 and then again in 1983. How completely did Tom dominate the Met scene during his long, if interrupted tenure? Let’s answer that literally. Seaver started 395 games for the New York Mets and completed 171 of them. By comparison, since 1992 — the year Tom Seaver became the first player inducted into the Hall of Fame bearing a Mets cap on his plaque — 148 different pitchers have started 4,528 games for the Mets and together they completed 167 of them.

Whoever said they don’t make ’em like that anymore wasn’t kidding.

Numbers say so much on behalf of Tom Seaver. So do images, such as those designed by the fabulous illustrator Warren Fottrell (a.k.a. Warren Zvon), a beautiful soul we lost in 2020. Warren did most of his speaking through graphic art, but he stopped by our blog on the occasion of Tom’s 75th birthday and left this comment:

Some people have a special type of integrity that can’t be described with words. Tom, throughout all his years in the spotlight, before and beyond, has been this type of person. Not only true to himself but true to the world around him. Not afraid to speak the truth. He wanted to be a winner but knew that the only way to truly be one was to take responsibility for being a loser when that was a required truth.

Over the years I’ve learned a lot from the mightiest of Mets aces, things he never intended to teach me and things I never set out to learn.

As a kid going to Shea, watching the Mets play, I wasn’t as big a fan as I am now. I took George Thomas Seaver for granted then.

He was simply our best pitcher.

But now, because of the way he has lived his life, the way he has consistently been the person he strives to be, I no longer do. I’ve learned that he is so much more than just a great Mets pitcher of the past, and when he goes a piece of me will go with him. A big piece.

So, yeah, Tom was the complete package, the greatest Met we’ve ever known, the greatest Met we’ll ever know. But his death is not the complete story when we look back at this year that has had far too much sadness, baseball-related or not. We are well aware we lost The Franchise in 2020. We should also remember the six other Mets who passed away this less than terrific year. Ray Daviault. Rick Baldwin. Les Rohr. Claudell Washington. Phil Linz. Mets fans rooted for them when they entered a game. Mets fans applauded when they did something good. Mets fans might have wished each of them had done a little more or stayed a little longer as Mets, but what they did in our uniform of choice deserves acknowledgement and another round of applause.

Seaver shared an affiliation with those guys, just as he shared an affiliation with the half-dozen Hall of Famers beside himself who died in 2020. I can’t imagine this year didn’t set a record for most baseball fans left mourning the loss of a personal favorite. Every player who’s ever played is some fan’s favorite, probably, but this year saw the passing of not just those we dare to call immortals, but those who defined their ballclubs.

Bob Gibson. Lou Brock. Joe Morgan. Whitey Ford. Al Kaline. Phil Niekro. They, like Seaver, were ballplayers kids idolized and adults revered. Gibson with the ERA nobody’s surpassed (the only figures lower were the batters he sent sprawling to the dirt). Brock who ran on everybody and collected more bags than Carrie Bradshaw. Morgan who sent the Big Red Machine into a whole other gear and made necessary the split screen for postseason telecasts, just so NBC could keep showing him leading off first. Ford with the World Series performances that were so historic that they knocked Babe Ruth out of the record books (the pitching record books). Kaline who won a batting title as a veritable baby and kept piling up base hits into middle age. Niekro the eternal elder who practically never stopped getting outs on the pitch he mastered better than anybody who’d ever lived.

It wasn’t just that they, like Seaver, were great. They were epic. They left indelible impressions on anybody who loved the game.

Bob Gibson became our assistant pitching coach, you might recall. It was 1981. Old teammate Joe Torre recruited him to give the Mets staff some attitude. It was not transferable, but the thrill of Gibby in a Mets uniform was something to behold. I was less thrilled at the thought of him knocking down an Agee here or a Milner there, but Bob had his reasons. Also, he was wearing a Cardinals uniform then. I wasn’t supposed to like him.

Bob Gibson became our assistant pitching coach, you might recall. It was 1981. Old teammate Joe Torre recruited him to give the Mets staff some attitude. It was not transferable, but the thrill of Gibby in a Mets uniform was something to behold. I was less thrilled at the thought of him knocking down an Agee here or a Milner there, but Bob had his reasons. Also, he was wearing a Cardinals uniform then. I wasn’t supposed to like him.

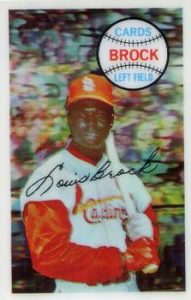

Lou Brock I never stopped liking, even on those occasions he was sliding into second ahead of the tag on a bullet delivered by Jerry Grote. Brock v. Grote never was fully settled, but we knew it was a case of the premier base stealer in the land versus an arm that was the envy of his catching peers. Only one of the people at the center of the battle that mesmerized Mets and Cardinals fans for a generation smiled much. Hence, though I pulled for Jerry to throw him out, I could never dislike Lou.

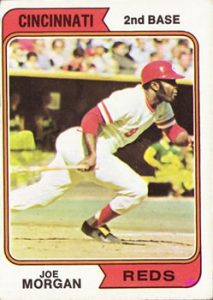

Joe Morgan was something else. At his height (no pun intended), Little Joe was a bigger deal on those powerhouse Reds than any of his co-stars, and his co-stars were frigging Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez. Getting Morgan to Cincinnati was like adding whipped cream to ice cream and syrup. It was already fantastic, but now you won’t believe what this concoction tastes like. I can still see him breaking from the box on his 1974 card. He’s probably gonna come all the way around.

Joe Morgan was something else. At his height (no pun intended), Little Joe was a bigger deal on those powerhouse Reds than any of his co-stars, and his co-stars were frigging Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez. Getting Morgan to Cincinnati was like adding whipped cream to ice cream and syrup. It was already fantastic, but now you won’t believe what this concoction tastes like. I can still see him breaking from the box on his 1974 card. He’s probably gonna come all the way around.

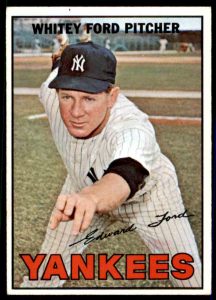

Whitey Ford was a name out of the past when I first heard of him, so far out of the past that my father said he saw him in high school. Not “went to see the Chairman of the Board at the Stadium” see him in high school, mind you. My dad was in high school and Ford was in high school and their schools played each other on one diamond or another. They were contemporaries, a couple of kids from Queens. Ford retired two years before I started watching baseball, which I found hard to believe once I learned his career spanned 1950 to 1967. I had scattered memories of 1967. My dad was my dad. Hard to put that together when you’re barely more than a tyke. I discovered not too long ago that Ford tried a comeback of sorts in 1968, pitching at Shea in the Mayor’s Trophy Game against the Mets. They didn’t score off him. Not too many did.

Whitey Ford was a name out of the past when I first heard of him, so far out of the past that my father said he saw him in high school. Not “went to see the Chairman of the Board at the Stadium” see him in high school, mind you. My dad was in high school and Ford was in high school and their schools played each other on one diamond or another. They were contemporaries, a couple of kids from Queens. Ford retired two years before I started watching baseball, which I found hard to believe once I learned his career spanned 1950 to 1967. I had scattered memories of 1967. My dad was my dad. Hard to put that together when you’re barely more than a tyke. I discovered not too long ago that Ford tried a comeback of sorts in 1968, pitching at Shea in the Mayor’s Trophy Game against the Mets. They didn’t score off him. Not too many did.

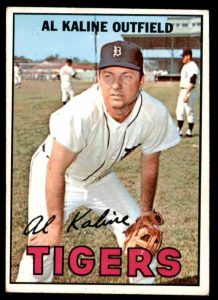

Al Kaline was part of the foundation of my baseball cognizance, one of the ’67 Topps my sister bequeathed me once it was clear I cared about the cards and she never would again. I gleaned from the back that he was the Tiger among all Tigers. He remained so into 1974 as he chased 3,000 hits and 400 homers. The former he got, the latter he missed by one (a moderate-sized disappointment to me the summer I was eleven and tracking his progress). Also in his last year playing for Detroit, I stared intently at a battery. It had the name of a great ballplayer. Alkaline. To this day I revel a bit when I pick up an alkaline battery. “It’s Al Kaline!”

Al Kaline was part of the foundation of my baseball cognizance, one of the ’67 Topps my sister bequeathed me once it was clear I cared about the cards and she never would again. I gleaned from the back that he was the Tiger among all Tigers. He remained so into 1974 as he chased 3,000 hits and 400 homers. The former he got, the latter he missed by one (a moderate-sized disappointment to me the summer I was eleven and tracking his progress). Also in his last year playing for Detroit, I stared intently at a battery. It had the name of a great ballplayer. Alkaline. To this day I revel a bit when I pick up an alkaline battery. “It’s Al Kaline!”

Phil Niekro dared stand in the way of Met destiny in 1969, throwing the very first pitch they’d ever seen in a postseason game. Fortunately, the Mets persevered in Game One of that maiden NLCS, but the outcome was no given, considering Niekro won 23 games that year (finishing second to Seaver for the Cy Young) and was on a path that would take him past 300 before he was done. He was another of those opponents I couldn’t help rooting for on the side. When I attended college in Florida, Phil was still pitching for the Braves, whose games I listened to on the radio. This was when Torre had taken over in Atlanta and I felt a kinship with his new club. I rooted hard for the 1982 Braves to win the pennant, mainly so Phil Niekro could finally pitch in a World Series. The Braves lost that NLCS, too, making Phil 0-for-2 in his best stabs at a championship. Nevertheless, he made the Hall of Fame without a ring. He also made it to Citi Field one September day in 2012 to help promote a documentary called Knuckleball! His role, on film and in actuality, was to mentor another late bloomer named R.A. Dickey. Watching them reunite during BP was a joy, as was the chance to ask Niekro a question about what it was like facing Seaver in the playoffs. He threw me a curve, telling me he saw his assignment as facing the Met hitters and “Seaver batted ninth.”

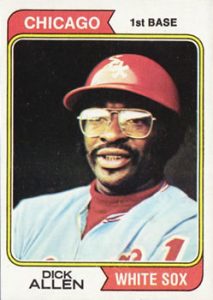

Maybe someday soon when we remember Hall of Famers who left us in 2020, we’ll add Dick Allen to the discussion. Allen isn’t in, but he’s come close via a veterans committee vote and is considered a favorite to cross the plate eventually. To Phillies fans in the ’60s, Allen was every bit the immortal that Seaver was to us and the aforementioned six were where they reigned. True, Allen didn’t necessarily mesh with Philly during his initial go-round, but those were complicated times. Nobody doubted he could mash (especially against the Mets), and everybody saw him put it together once he landed on the White Sox in 1972. When he died, I was moved to call up the image of his 1974 card. There he was, relaxed in the dugout and looking as he was to me when I was eleven: the coolest man in the majors.

Maybe someday soon when we remember Hall of Famers who left us in 2020, we’ll add Dick Allen to the discussion. Allen isn’t in, but he’s come close via a veterans committee vote and is considered a favorite to cross the plate eventually. To Phillies fans in the ’60s, Allen was every bit the immortal that Seaver was to us and the aforementioned six were where they reigned. True, Allen didn’t necessarily mesh with Philly during his initial go-round, but those were complicated times. Nobody doubted he could mash (especially against the Mets), and everybody saw him put it together once he landed on the White Sox in 1972. When he died, I was moved to call up the image of his 1974 card. There he was, relaxed in the dugout and looking as he was to me when I was eleven: the coolest man in the majors.

Qualifying for Cooperstown isn’t a prerequisite for leaving an impression, not when you were a kid who collected cards and listened to games and took the announcers at their word. Bob and Ralph and Lindsey were always respectful of and effusive over the likes of Denis Menke and Bob Watson and Glenn Beckert (even if he was a Cub) and Lindy McDaniel (who always seemed to be notching a save for the Yankees) and of course Jimmy Wynn the Toy Cannon, as if it that was how it appeared on his driver’s license. Jay Johnstone was considered a real card (even if he never played for St. Louis). Biff Pocoroba caught in Atlanta and got a rise out of everybody when they heard his mellifluous name called. Horace Clarke was a misunderstood staple in the Bronx at second. Roger Moret was almost unbeatable for a spell in Boston. I had plenty of Bart Johnsons and Ed Farmers in my shoeboxes. I probably had a few Adrian Devines, too. Tony Taylor was endlessly dependable. Ron Perranoski helped revolutionize relieving. A little before my time but just in time for me to cherish his ’67 card was Lou Johnson of the Dodgers. A little later, but just in time to frustrate the Mets for the final time during the 1986 regular season, was the Expos’ Bob Sebra, who outdueled Ron Darling the final week of the year to remember.

Kim Batiste of the Phillies. Damaso Garcia of the Blue Jays. Matt Keough of the A’s. Ted Cox who stirred prospect hype with the Red Sox before they traded him to Cleveland. Tommy Sandt. Ed Sprague. Bob Oliver. Mike Ryan. They were pictured on cardboard. They were performing on television. They were important because we love baseball. They were important to those who knew and loved them, too, of course. For their families and friends, they didn’t have to be baseball players on baseball cards. Isn’t it something that actual people stand behind those images?

Eddie Kasko, who I remember as a manager of the Red Sox, died in 2020. John McNamara, who we all remember as a manager of the Red Sox, died in 2020. Billy DeMars, who I remember coaching for the Phillies forever, died in 2020. Jim Frey, batting coach and father figure to rookie Darryl Strawberry before he left to steer the Cubs past the Mets in ’84. Hal Smith, who isn’t the hero of the 1960 World Series but made it possible for Bill Mazeroski to be because he also hit a dramatic home run. Don Larsen, who threw a perfect game in the World Series in 1956 (as if that’s a sentence to type in a nonchalant font).

Four of the heretofore 17 surviving New York Giants: Gil Coan, Johnny Antonelli, Mike McCormick, Foster Castleman. Antonelli won 25 games for the 1954 world champions; the Mets acquired him for 1962, but Antonelli opted to retire. McCormick won a Cy Young in ’67, still a Giant in San Francisco. Now there are 13 surviving New York Baseball Giants. I get together with other lovers of the New York Baseball Giants over Zoom these days. We used to get together at an East Side bar called Finnerty’s, an establishment usually devoted to serving Bay Area fans. That place, like too many that depend on people being out and about, didn’t survive 2020’s pandemic ravages. Same for a Midtown sports bar very close to the hearts of myriad New York baseball fans, yours truly included, Foley’s.

“Young man!”

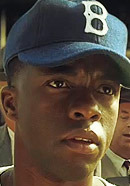

That was my favorite line from the movie 42 because it was what the actor playing Jackie Robinson said to the actor playing a young Ed Charles. We know who mature Ed Charles grew up to be. We also got to know the actor playing Jackie Robinson as one of cinema’s brightest stars, Chadwick Boseman. He died on rescheduled Jackie Robinson Night in 2020 at the age of 43.

Young man, indeed.

I went to a game in 2019, which seemed unremarkable as an event because going to a game is what a person who loves baseball routinely did prior to 2020, except this was kind of a special game for numerous reasons. One of them was I found myself sitting in the same section as the family and friends of the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates, right next to the wife and child of outfielder Starling Marte. Mrs. Marte urged her youngster to cheer “Daddy” on every time he batted. Steven Matz was pitching a shutout, so I didn’t particularly want Marte to succeed, but I have to admit I did get a kick out of the cry. When Big Daddy Marte was rumored to maybe be coming to the Mets, I hoped a little it would happen given my (admittedly tenuous) connection. When I learned in May that Noelia Marte, all of 32, had died of a heart attack, I felt the connection again.

I went to a game in 2019, which seemed unremarkable as an event because going to a game is what a person who loves baseball routinely did prior to 2020, except this was kind of a special game for numerous reasons. One of them was I found myself sitting in the same section as the family and friends of the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates, right next to the wife and child of outfielder Starling Marte. Mrs. Marte urged her youngster to cheer “Daddy” on every time he batted. Steven Matz was pitching a shutout, so I didn’t particularly want Marte to succeed, but I have to admit I did get a kick out of the cry. When Big Daddy Marte was rumored to maybe be coming to the Mets, I hoped a little it would happen given my (admittedly tenuous) connection. When I learned in May that Noelia Marte, all of 32, had died of a heart attack, I felt the connection again.

“Pat Cawley of Glendale” was the State Farm Agent of the Day on basically every SNY telecast for years; Gary, Keith and Ron spoke of him as if he was a relation. Suddenly one night this offseason I saw Pat passed away. He was only 55. Luke Gasparre greeted me and who knows how many fans from his post atop Section 310 at Citi Field. Luke ushered at Shea Stadium for the life of the old ballpark and did the same through the first decade of the new ballpark. The World War II veteran died this year, too, having lived to be 95. Claire Shulman became Queens borough president in 1986 and had the honor of presiding as the Commissioner’s Trophy came home to Flushing — she also showed homeland loyalty by making municipal bets on behalf of the Mets during various Subway Series conflicts. Shulman died in 2020 at 94. Roger Kahn, who made Brooklyn even more famous than it already was via The Boys of Summer, signed off the beat for good at 92.

“As an old National League fan,” Pete Hamill reflected in 2000 of the interborough Fall Classic just completed, “I was rooting for the Mets.” Hamill’s report in The Subway Series Reader, which was maddeningly evenhanded, took the time to celebrate the Mets’ lone win, in Game Three, particularly Benny Agbayani’s exploits. “Instantly,” Hamill wrote, “hope rose for millions of Mets fans.” Sort of like it did for readers every time they saw Pete Hamill’s byline. We wouldn’t see it again after his passing in 2020 at the age of 85.

In the midst of that World Series, I wrote as much as I could to every Mets fan whose e-mail address I had. One of those fellow Subway Series travelers was a former colleague named Jim Ryan. Jim had sold advertising at the magazine I edited. He wasn’t a me-level Mets fan, but Shea was where his sympathies resided, which was no small thing when you worked in an office in New York in the Baseball Chernobyl years that followed 1996. I still remember Jim’s reply to whatever I wrote coming out of Game Three. He scored a ticket for the game and reported on a peanut vendor who, like Berra to Linz in 1964, told some overly loud Yankee bellower to stick it. Jim was so impressed that he claimed to have bought out the vendor’s entire stock on the spot.

Jim knew how to execute a grand Met gesture. Two years earlier, in 1998, Jim asked a friend of his who worked for the Mets to arrange for a dream of mine to come true. The dream was embedded so deeply in my subconscious that I don’t know that I dared speak it unless specifically asked. In the course of conversation, however, I revealed to Jim that I had never set foot on the field at Shea Stadium. Others would have nodded and shrugged. Jim made it happen. He arranged through his friend to get us on the VIP list for the DynaMets Dash one Sunday after the Mets played the Braves. We were very big kids to be taking part in this decidedly youth-oriented promotion, but they didn’t have the dash when I was 14 & under. So we ran the bases as if we weren’t too old for such glorious nonsense.

When I divined in September that Jim Ryan, 54, died of a heart attack, I was back on the field with him again, each of us dashing (he was way more dashing than I was), each of us laughing that we were part of this. I was in the office with Jim, too, sharing a stray moment related to some client of his or some story of mine or some ’70s song we both loved. When word spread through channels that Jim had passed away far, far too young, I noticed two of my fellow co-workers from those days used the same term to describe Jim: a friend to all. It was true. Everybody liked him and nobody didn’t like him. We were never incredibly close, but in those passing minutes that make a day and a week and a big chunk of your life before you know it, he was a friend to me, and I appreciated it. I still do.

Wonderful column. So poignant. Sunday Morning’s Hail & Farewell segment left them all out. An oversight that I would surely have pointed out when I used to mix that soundtrack every year. My AL hero was Kaline too. I asked Hamill about Ebbets Field at the NY Tenement Museum. And Kahn at a UCLA book talk a few years ago. As he wrote, ‘I worked for a newspaper that no longer exists, for a team that is gone, in a ballpark that’s demolished.’ Truly a 2020 epitaph. And Scully, who remains with us, kindly answered all my questions about his years in Brooklyn, when I worked with him for CBS Radio. Maybe my dad took me to a game there, but I was only 5 or 6 years old. No memory or evidence. Here’s to a better 2021. And happy birthday from LA!

Beautiful tributes, Greg.

Thank you so much for the journey down memory lane. I too had fond memories of all these human beings who gave us joy in the celebration of our ‘pure’ National Pastime. Thank you again. And all the best for a Happy and Healthy New Year.

Beautiful tributes. Daviault’s victory was the first Mets game I ever attended in person.

Wonderful as always Greg. Beautiful and moving.

Let’s just get through one more day – and it’s on to a better year!

Very nicely done, Greg.

Fun fact about the Phil Linz harmonica incident. That winter he got an endorsement deal from Hohner, the company that has made probably 99% of all harmonicas any of us have ever heard played. I read that this deal was for $10,000, which was likely more than he was making playing baseball in 1964. So perhaps he was a harmonica player (harmonicist?) who in his spare time played baseball.