On November 8, the Monday before last, Edgardo Alfonzo turned 48. On November 16, this past Tuesday, Dwight Gooden turned 57. On November 17, today, Tom Seaver would have turned 77. Being a diehard fan means knowing when your favorite players — Tom, Doc and Fonzie are my Top Three — began to live. Being a diehard fan also demands your fandom and your appreciation of what and who you’re a fan of be taken seriously. Not everybody takes your demand or your fandom seriously, so when you come across those who do, you appreciate it. Given that this is the birth month of so much Met greatness (even the Met skyline logo was unveiled in November of 1961), November seems as good a time as any to appreciate those who’ve appreciated what it means to appreciate.

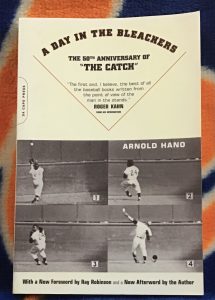

Arnold Hano, a book editor himself in 1954, inadvertently invented the literary form you read here and any number of places on a regular basis in the 21st century. It wasn’t called fan blogging, but he wrote seriously about being a fan: about wondering whether he should try to get a ticket for the game; about how best to travel to the game (opting for the short walk and long ride of the D train uptown from 59th St.); about the line that was already formed as he attempted to get into the game; about staking out his seat; about the fans sitting around him; about the view; about the food (“I had subsisted on two hot dogs, one beer and two cigars”); about the weather; and about the game itself in a very subjective manner.

The game was only the game in which Willie Mays made what is now known as The Catch. Nice game to pick, especially since what Mays was going to do couldn’t be known in advance. The World Series was in town. Arnold Hano was a Manhattanite and a Giants fan. The Giants were in the World Series. How could Hano resist? There were reasons, actually, mostly centered on supply and demand. But Hano threw himself into his quest, picking a subway, queuing up at the Polo Grounds, waiting out a low hum of anxiety over how many bleacher spots would be available as he berated himself over not arriving earlier, and eventually parting with the two dollars and ten cents it would take to gain admission.

Hano got in and basically birthed the blog. He wrote about what we would write about five, six, going on seven decades later. He wrote about having to fork over fifty cents for a fancy souvenir program when all he wanted was “the old-fashioned everyday kind of program with a scorecard, the kind that sells for a dime”. He expressed dismay that some people feel it necessary to watch a live baseball game right in front of their eyes with the aid of a newfangled portable radio. He’s disdainful of the nearby lady Brooklyn Dodgers fan who has converted for the day to the cause of the American League champion Cleveland Indians (his takes on Dodgers and Yankees fans in general are what we’d today call hot). He hasn’t much use for many of the bleacherites around him. Hano came to see the game, but he sees all and reports back.

And he does it without an enormous video screen replaying every play, never mind the cues of Russ Hodges’s play-by-play. Hano sits hundreds and hundreds of feet from home plate yet discerns fastballs from curveballs because that’s how you had to roll at a baseball game in 1954. That’s what he’d been doing since discovering baseball in the 1920s. Young Arnold had been sent to while away summer afternoons at the Polo Grounds the way other kids were sent to day camp. He’d lived practically upstairs from the field, on Edgecombe Avenue, and his cop grandfather had a season pass to seats in the grandstand. Over time, Arnold decided he liked it better in the bleachers, where fans could eschew decorum and just be fans, even the ones he kind of rolled his eyes at as Game One of the World Series got underway.

The percentage of the population that can claim to know what it was like to go to a World Series game in 1954, to see the New York Giants, to see the Polo Grounds, to see 23-year-old Willie Mays running down the longest fly ball imaginable off the bat of Vic Wertz and then turn and throw it into the infield pronto is forever dwindling. Hano’s book, published in 1955, preserves all of that. The morning chill. The afternoon sun. The weirdo parading through the bleachers between during the seventh-inning stretch soliciting donations to buy each and every Giant a wristwatch or a Cadillac or some expensive token of appreciation…or so the weirdo swore. The game. Of course the game. The game that locked in at 2-2 and stayed that way into the tenth inning. Hano is all over The Catch Mays made on Wertz’s drive, but he’s all over everything.

“In the Giant tenth,” Hano notes after Cleveland manager Al Lopez has pulled out all the stops only to remain in a tie, “the Indians were down to a substitute first baseman, a substitute shortstop, a substitute right fielder, and a substitute catcher,” which is about as trenchant an observation as I’ve ever read about going to your bench and coming up empty. Bob Lemon — “a tired, very courageous gentleman” — is still at it on the mound for the visitors. Starting pitchers didn’t necessarily stop at nine innings (or nine pitches) in 1954, and partisans weren’t shy in their admiration for the enemy.

The game ends when pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes takes advantage of the generous right field dimensions, “smiting the ball just as far as was needed” for a 5-2 Giants win that set the stage for a Giants four-game sweep over the heavily favored Indians. The other underdog turned hero from the story is Hano, who publishes the book, continues his career as a writer and advocate for more than sixty years beyond publication, and lives until the eve of the 2021 World Series. When word of his passing at 99 spread last month, I took A Day in the Bleachers off my bookshelf and reread it during the first two games of this year’s Fall Classic. Hano on the Giants and Indians made the Astros and Braves on Fox far more palatable than I could have fathomed.

It’s kind of crazy, but it’s definitely happening. Jim Lampley, a familiar national sportscaster comes on after the first sports update at 3 PM, which itself is delivered by New England-accented Suzyn Waldman. Howie Rose, whom we know as the lone holdover from WHN, thanks to his new show Mets Extra, follows, bringing us to Mets baseball, rain delay and all. Because the Mets’ flagship is now an all-sports station, we aren’t sent back to the studio for the best of Merle Haggard and Loretta Lynn, their considerable talents notwithstanding. Howie stays on and keeps talking sports until the tarp is pulled. Bob Murphy and Gary Thorne take it from there, painting the word picture of the critical Mets’ 9-6 victory over the Cardinals, the otherwise frustrating Mets pulling to within 5½ games of first place.

Then, after the postgame edition of Mets Extra, to carry us through after midnight and before dawn is a warm, throaty voice that is more fan-friendly than radio-typical for 1987. He is not smooth like Lampley or the promised morning man Greg Gumbel, who we recognize from television. This guy we don’t recognize at all. He is a lot of shtick at first listen, yet the shtick sticks. It stuck on me instantly and it stuck around for the next 34 years.

Steve Somers was one of the original voices of the FAN and the last to stay in a regular time slot from the station’s inauguration until just this week. He was Captain Midnight in the late 1980s until the mid-1990s. Then he moved around the schedule some, landing for keeps in the evening/late evening. Steve who came from San Francisco fashioned himself into a native New Yorker around his 40th birthday. He belonged here all along. He fit most comfortably overnight talking sports — a lot of Mets, in particular, as the Metropolitans became his baseball team — and talking life from somewhere in Astoria. Other hosts wanted to let you know how much they knew. Steve insisted over and over again there was no such thing as an expert. Other hosts lost patience with callers. Steve let them go on because it was the middle of the night and he was grateful anybody was on the other side of the phone let alone the other side of the glass. As his nudged if not forced retirement moved into focus this fall, he and those who valued working with him and talking to him came on to schmooze with him, mostly about what it was like all those years ago first hearing him.

WFAN, ensconced at 660 AM since October 1988 and simulcast over 101.9 FM in November 2012 (plus whatever name the app goes by presently) can wear on the modern ear quickly, perhaps because we’ve all trained ourselves to conduct a sports radio show in our head, but no radio station has ever been better about mythologizing itself. When a WFAN voice with ties to the station’s beginnings commences a dialogue with another voice with ties to the station’s beginnings — turning the clock back to July 1, 1987, and the dial up to 1050 AM — it reminds us that we as fans who were tuned in the second WHN signed off from playing country music were about to be taken seriously like we’d never been taken seriously before. Any time, day or night, somebody was likely to weigh in on Darryl Strawberry. Whether they made any sense or not didn’t matter. I kept reading in the papers back then that an all-sports format would never work. Suddenly superserved by one, I wondered how an all-sports format hadn’t already existed. There were a lot of us out here. We were up at all hours. I was in my night owl mode when Steve Somers landed in New York. I never called him, but I was sure he was schmoozing in my direction, certainly in my wheelhouse.

He did this one bit for a while that has stayed with me. Every night (or morning) at 3 A.M., he would play “Night Moves” by Bob Seger, using it to soundtrack the essence of his autobiography, hailing the night as the time when you could sit in your solitude and contemplate your future and where it might take you. There’s a line Seger has in there about a girl he knew when he was young. You know: a black-haired beauty with big dark eyes, and points all her own, sitting way up high…“way up firm and high.”

Without fail with “firm and high,” Steve would interject, “she went to a good school.” Every night I knew it was coming and every night it cracked me up.

This is all according to the official Nassau County website and it’s a little relevant to our conversation because nearly 124 years later, the Queens Baseball Convention gaveled into operation not in Queens, but in neighboring Nassau. Actually, I don’t think a gavel was involved. Nevertheless, jurisdictional niceties may have seemed slightly confusing to those looking at QBC last weekend and wondering what it was doing convening outside the home borough of Mets baseball.

It was making for an Amazin’ time, of course. QBC always does that, no matter where it is. But if the geographic thought did enter the intersection of one’s thoughts, it should have scurried along quicker than the traffic on Sunrise Highway. Metsopotamia, after all, is a state of mind, and Mets fans don’t have to be in Queens to congregate with other Mets fans. QBC proved that in Wantagh on Saturday. I, for one, was delighted by the latest location of the only For Mets Fans By Mets Fans fanfest in operation because, quite frankly, it was a helluva lot closer to where I live than it used to be.

Convenience! It’s not to be underrated nor overlooked. Because QBC paid homage to Queens’s former borders, I didn’t have to schlep on various Long Island Rail Road and subway trains to meet it more than halfway. Instead, I hopped in my sturdy Toyota (it predates Nassau County’s centennial) and zipped across side roads to Mulcahy’s of Wantagh. It was so convenient, I did it twice. Stephanie, you see, was very much up for QBC, maybe not so up for the full seven or eight hours it goes on. No problem, honey, I gallantly said to my wife. After the first couple of hours, I can take you home and head right back. (She offered to take the LIRR, which was also convenient to Mulcahy’s as well as thoughtful on her part, but I wished to revel in my rare alignment with the defining feature of suburbia.)

Location, location, location, as they say in real estate. Affinity, substance, bonhomie, as we say in fandom. Put them together, and you had the keys to what made this QBC as wonderful a QBC as any of those where the Queens aspect was literal. It was worth reaching by any conveyance, wherever you were coming from. It was so nice it was worth reaching twice. It contained such a storm of Metscentric activity that you barely noticed the tornado flying through nearby if not frightfully nearby portions of Nassau County. At one point an announcement was made about a tornado warning — we don’t get many of those around here — and things grew a little eerie for a few minutes, but nature looked kindly on our gathering at Mulcahy’s Pub and Concert Hall and conveniently left Wantagh alone.

My primary reason for attending QBC was to play a role in handing out the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award. It doesn’t usually take more than one set of hands, but this was a very special presentation, to the family of the late Shannon Forde. If you asked everybody who treasured their relationship with Shannon to help hand out this award, we’d still be there.

I was honored to represent the blogging community. Mets fan blogging began in earnest in the 2000s. Shannon, whose job with the Mets was in media relations, was one who took notice and took action. She invited a bunch of us bloggers to Citi Field as media. She saw the likes of us as a legitimate vehicle that delivered information and perspective to Mets fans. Probably not everybody in her job would have reached out. Shannon went extra miles to make sure we were communicated to by the Mets so we could communicate a little better to the Mets fans for whom we wrote. The “mother’s basement” stereotype was still rattling around then. If you dismissed bloggers’ existence, you didn’t have to pay attention to what they blogged.

That wasn’t Shannon’s style. She treated us like she treated everybody within her professional purview: with nothing but good humor and implicit respect. Shannon took our little cohort seriously, maybe more seriously than some of us took ourselves. It wasn’t just that she invited us out to the ballpark. She waved us inside spaces where most of us would never have otherwise set foot. It was as if she ran around to a side entrance, held a door open for us, and told us, “It’s OK, come on in, you belong.” She understood we who weren’t card-carrying members of the BBWAA may have required a little TLC at first, yet she never approached us as anything less than professionals.

Shannon believed we had a place there as people who were simply trying to tell the Mets’ story in our own individual ways to readers who simply wanted to understand the Mets from every angle possible. We the fans who blogged represented the fans who read. Shannon got that. She provided us a runway to hone our insights and present our team in ways we couldn’t have otherwise. It’s hardly the only reason QBC wanted to acknowledge her, but a lifetime of kindnesses of that nature add up. When she died at 44, everybody who’d come in contact with her praised her for her skills, her professionalism, her trailblazing and, most importantly, her humanity. Gil Hodges left us in 1972, Shannon Forde in 2016. It’s never too late to say a good word on those who made their world better.

The rest of my non-commuting QBC day, given that the organizers didn’t burden me with any other official responsibilities, was dedicated to listening to other folks on stage and hanging out with Mets fans all over Mulcahy’s. There was a lot of hanging out. There were a lot of Mets fans. Mets fans I’ve known for years. Mets fans I was just meeting in person. Mets fans I hadn’t seen since the last QBC in 2019, who I mostly see at QBCs. It was as if my social media feeds had sprung to life, but only the pleasant threads.

Syndergaard plays in an era with movement and money. God bless, as they say. Were justice prevalent prior to the challenge Curt Flood brought to the reserve clause system, every player could have explored the marketplace. Ron Hunt, a Mets fan favorite fifty years before Syndergaard came along, played major league baseball in the 1960s and early 1970s. There wasn’t free agency. Hunt’s career was over the same year Catfish Hunter extricated himself from Charles Finley on a technicality, a year before Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally went before an arbitrator named Peter Seitz and won players the kind of freedom Flood had so nobly sought for himself and his peers.

Hunt missed all of that. But Ron, for a long time baseball’s career leader in getting hit by pitches, gave his all to the game and the people who support it. That was and remains his guiding principle as a ballplayer and ballplayer emeritus. As he has told Ken Davidoff, his de facto Boswell in the New York Post — and as he mentioned to me when I had the good fortune to speak briefly with him — he made his career about the fans. I saw it when Hunt appeared at Citi Field in 2019. I met Mets fans who became Hunt fans in 1963 and 1964 and never stopped rooting for the guy regardless that he was traded away. To them, he never stopped being a Met. To him, Mets fans never stopped meaning the world.

Davidoff recently updated his ongoing Hunt chronicling by reporting that Ron’s battle with Parkinson’s disease has stiffened. The good news is there is a treatment that has made his life better. The bad news is the prohibitive expense to keep it going. Ron’s daughter has worked with one of his longtime fans to establish a GoFundMe page to get her dad access to what he needs. Fans have responded, just as Ron has always responded to fans and just as Ron worked hard on behalf of the Baseball Assistance Team when he saw other players in need of help.

Ken’s latest story is here. The fundraising page is here. I thought you might like to know about it.

The Giants should not have left NY. The Mets should not have left WFAN and were better off at WOR than CBS AM.

You could tell with Steve Somers for at least the last year or so it was time, at least as a regular host. Longtime, if not original, hosts Tony Paige, Mike Francesca, Joe Benigno, Steve Somers, plus anchors John Minko and Harris Allen, out. Mark Chernoff no longer running the ship. Quite a turnover. They’re missed.

Steve Somers was always a favorite of mine, especially as I was driving home fron Shea, after listening to the post-game from Howie Rose.

My favorite Somers bit was when he played the song ‘He’s a

Cold-Hearted Snake,’ and then interspersed it with himself saying ‘George Steinbrenner.’

A Classic.

Thanks for the Ron Hunt links. I made a small donation with a brief note about having been to the 1964 All Star Game and seeing his base hit. His daughter responded with what appears to be a non-automated thank you. That was sweet.

BTW, they are very close to their goal, which seemed to be quite a lofty number, so good to see.