When Yogi Berra died in 2015, Dave Hillman ascended to the role of Oldest Living Met. Yogi Berra is among the most famous baseball figures of the past 75 years, perhaps ever. People still quote Berra, still invoke Berra, still remember Berra. He’s been gone seven years, but his legacy is likely to live on for generations.

When Darius Dutton “Dave” Hillman succeeded Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra as Oldest Living Met, I had almost no idea who Dave Hillman was, other than “member of the 1962 Mets,” and then mostly from looking at a list of the vital statistics I keep of Every Met Ever: birth date; date of first game as a Met; date of last game as a Met; and, where applicable, death date. Sad to say, I just the other day tabbed to the last column on Dave’s entry and made the necessary revision to his line on the list. Dave died Sunday in Tennessee at age 95, ceding his title of Oldest Living Met to Frank Thomas, 93.

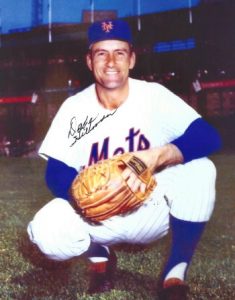

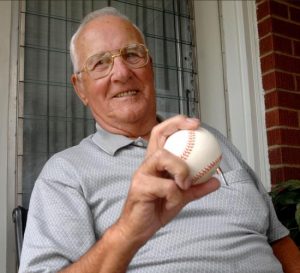

Dave Hillman threw his first pitch for the New York Mets on April 28, 1962, becoming the 29th man to play for them overall. The chronological numbering is modestly significant if you want it to be. The first 28 Mets were the Original Mets who made it out of Spring Training. They won one game with that initial crew — and lost eleven. While cutting down their roster to the mandatory 25, they opted to make some changes besides. Their first in-season moves included bringing in righty Hillman, who washed out in Cincinnati following a robust season of relief in Boston.

In pursuing Dave, a friend also named Dave reminded me, the esteemed Met brain trust of George Weiss and Casey Stengel passed on the opportunity to sign none other than future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, whose right arm at that moment was considered more done than Dave Hillman’s (the almighty Yankees dropped him), yet actually had several decent seasons left ahead of him. Had the Mets taken a chance on a four-time 20-game winner then at liberty, Robin and fellow Phillie expatriate Richie Ashburn might have shared dugout time reflecting on their Whiz Kids exploits; sizing up their Cooperstown prospects; and plotting to elevate the Mets to a record slightly better than 40-120. But that was a road the Mets were adamant about not taking. “I have spoken to Casey Stengel,” Weiss practically harrumphed, “and he is definitely not interested in Roberts.”

Robin posted double-digit win totals in 1963, 1964 and 1965. His final game in the majors came on September 3, 1966. For context, eight days later, Nolan Ryan debuted. Robin Roberts, 35 in April of 1962, lasted quite a while, Weiss’s or Stengel’s interest in him be damned. Like Roberts and Ashburn, Stengel and Weiss are in the Hall of Fame. Alas, even in the grandest of careers, not every pitch is a strike, not every swing is a hit and not every move proves the best choice in hindsight. The Mets needed a pitcher at the end of April 1962 and went with Hillman. Dave’s major league journey began in 1955 with the Cubs. He was, in the most honorable sense of the phrase, a journeyman pitcher. A journey that takes a man to the Polo Grounds and assume the mantle of (almost) Original Met can’t help but be honorable in our eyes.

The date of the first game Dave Hillman ever pitched as a Met stands as absolutely significant. April 28, 1962, marked the first Mets home win ever, over the Phillies. Jay Hook started and was hit hard. Bob L. Miller entered before the first was over and eventually allowed the visitors to extend their advantage. Dave, however, stood to be the winning pitcher after departing his one inning of work, the sixth, and the Mets taking the lead directly thereafter. The official scorer disagreed, taking into account a) the first batter Dave faced in the sixth (Don Demeter) leading off with a home run; and b) Met ace Roger Craig, the club’s Opening Day starter, coming on and throwing three scoreless innings to seal the 8-6 victory. Craig could have been credited with a save, but saves hadn’t gained official statistical traction by 1962, so Roger was awarded the win. Scorer’s discretion, as they say.

At least Dave Hillman was in the big leagues again and at least he took part in a New York Mets win…a historic New York Mets win. So did newly acquired Sammy Taylor and newly acquired catcher Harry Chiti. Chiti, while no Berra at or behind the plate, would become famous in a very Metsian manner a little later in 1962, returned to Cleveland when the Mets decided he wasn’t the receiver for them. The player to be named later turned out to be named the player named Chiti. This transaction went down in Originalist lore as Harry Chiti being traded for himself. Harry batted .195 and was never quoted on the subject of what to do when you come to a fork in the road (“take it” — Y. Berra), but his aftermath read as colorful.

Dave’s Met tenure left fewer footprints in franchise legend and was not much rosier in the way of statistics. He’d contribute to a few more wins and a whole bunch of losses — the song of essentially every 1962 Met — almost exclusively in relief. He notched the sixth save in Mets history. The sixth save in Mets history materialized in the Mets’ 51st game overall, an indicator less that starting pitchers went deep in those days than there weren’t many Met wins to save. Still, it was pretty clutch pitching. Dave came on in the eighth and popped up former teammate Ernie Banks with runners on, then stranded the bases loaded to finish the ninth. That the win Hillman secured improved the Mets’ record to 14-37, or that Hillman’s ERA for the year (including his stint with Cincy) hovered above 8, does not detract from a Mets win being a Mets win nor Hillman making sure it didn’t evolve into something less. In 1962, every win was sacred.

Three appearances later, Dave Hillman sported an ERA under 7, which was progress. It was also the end of the line for an eight-season veteran who’d certainly overcome obstacles to be able to put that many years into big league ball. The Mets wished to send Dave to the minors. Dave wished to move on, specifically back home to Kingsport, Tenn. — you might recognize the town as site of a long-running Mets farm club — with a career in clothes retailing in front of him. The 29th Met ever also became the seventh major leaguer to play his final game as a more or less Original Met. Forty-five players in all were 1962 Mets. Nineteen of them would never play again in the bigs after serving the 40-120 cause (Chiti, who Cleveland sent down to Jacksonville upon reacquiring him, was the sixth of them). In a 2008 interview, Hillman said of his last team, “It was a joke, the ballplayers they had assembled. It was all old players who were over the hill. There were one or two young pitchers that were good, but with the ballclub, they couldn’t get them a run.”

Hillman, nearing 35, may have resembled that remark, but he wasn’t inaccurate in his scouting report. And he couldn’t be blamed for considering the path of his baseball journey, which had landed him at being told he wasn’t quite good enough for those tenth-place Mets, and deciding trying to get it together at Syracuse wasn’t his best next step. Selling clothes at a store with his family’s name on the door (Fuller and Hillman, owned by his uncle) had more of a future to it than an excursion to Triple-A. This was 1962. Eight years in the big leagues didn’t set a person up for life. Life had six more decades to it in Hillman’s case. He’d be recognized from time to time for having been a ballplayer and he’d kindly answer inquiries about having been a Met or a Red or a Red Sock or a Cub way back when, but he wasn’t, when one ventured outside the borders of Kingsport or completism, what you’d call famous.

Then the famous Yogi Berra died, and Dave Hillman may or may not have thought much about inheriting the status of Oldest Living Met, a distinction that carried with it a note of renown or at least curiosity. I’d see his name and his birth date and get a little curious. When he died at 95, I poked around a little more. The Mets were a small segment of a life that went on and on, the longest life any Met has ever known. Being a 1962 Met wasn’t necessarily Dave Hillman’s calling card. But it’s how we came to know him or know of him. We thank him for the pleasure.

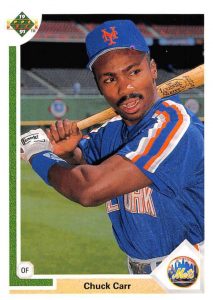

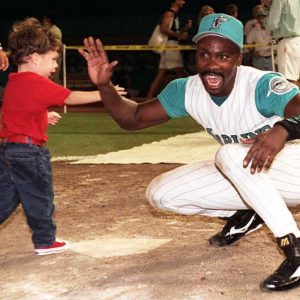

The 1993 Marlins featured atop their lineup and tearing around their bases Charles Lee Glenn “Chuck” Carr. Chuck was known in some circles as Chuckie. He’d refer to himself that way first-person style, as athletes exuding self-confidence have tended to do. He’d be referred to that way by colleagues, with varying degrees of affection or disdain. I have one overriding memory of the baseball career of Chuck Carr, a gifted outfielder who died at the indisputably too soon age of 55 on November 12, and it comes from 1993, three years after he’d broken into the big leagues as a New York Met, two years after the New York Mets decided they’d seen all they’d needed to see of him before making him a former New York Met.

It was, I’m pretty sure, from a morning in late June of ’93. The Mets were already certifiably dismal. I mean worst team money could buy dismal, and this was with cognizance that there was a book out that spring about the previous year’s Mets and it was called The Worst Team Money Could Buy. This team was worse. Much worse. But, as even the worst Met teams do, it cobbled together its moments, and one it desperately needed came at the expense of those expansion Marlins. On the night of June 29, following an extended stretch of the worst baseball I’ve ever seen the Mets play — they’d lost 48 of their previous 63 games, which translated to a winning percentage of Basically Never — they limped into Joe Robbie Stadium on a Tuesday night. They had been off Monday. On Sunday, at Shea, Anthony Young had lost his record-setting 24th consecutive decision. The Mets, not just Young, hadn’t won since the Monday before that, a victory that itself was the first since the Monday before that, which itself was the first Met win since the Monday before that. Garfield the Cat hated Mondays. The Mets by June of 1993 were the personification of them. No wonder it’s the only day when they won.

Storm clouds followed the 1993 Mets everywhere. Natch, they’d meet them upon their inaugural visit to Joe Robbie, which would become notorious for summertime rain delays over the next eighteen years, which is why they now play in Big Empty Park with a retractable roof downtown. The damp notoriety began in earnest on the next-to-last night of this particular June. It wasn’t so much that precipitation came blowing in hard on the Mets and the Marlins after three innings. It was that the grounds crew of the facility hadn’t been schooled on the proper method for unrolling and spreading out a tarpaulin. Tim McCarver grew quite amused that right field was well-tarped…which was quite an accomplishment…if that was the goal…which it wasn’t.

In assessing the left side of the infield as “absolutely inundated with water,” Tim took a page from Joe Namath’s most memorable trip to Miami. “I guarantee you,” Tim promised, “that shallow right is dry as a bone!” The men in teal tops and tan shorts missed most of the infield with their efforts, meaning a lot of futile dragging was done in a downpour before the crew rerolled and tried again. The Joe Robbie PA commented on the action like any good movie soundtrack, blaring the theme from Mission: Impossible.

“What,” McCarver asked Ralph Kiner with trademark incredulity, “is going on?” That had been the sentiment surrounding the Mets for nearly three months of a season gone awry. Tim thought about it some more and declared that for the dugout-sheltered players watching another team — “the wet brigade” — struggle, “this is the most fun the Mets have had all year!” By the time the crew, supplemented by additional stadium personnel, hit its mark and covered the entire infield, the rain had come to a full stop. Even Eddie Murray paused from his two-year commitment to taciturnity and broke into a grin.

Fun somehow became the watchword of that Tuesday night, provided the 21-52 Mets hadn’t sucked the good humor out of you and you didn’t mind staying up late. The tarp was eventually taken off the field (no crewmen were lost) and the Mets managed a 10-9 win. “Managed,” as in after the delay of 88 minutes, the Mets broke a 1-1 tie in the fourth; built a 6-1 lead in the top of the seventh; gave it back when the Marlins scored seven runs in the bottom of the seventh; grabbed the lead anew on three runs in the eighth; saw the Marlins even it up in the bottom of the ninth; and finally go ahead for good in the twelfth. Time of game: 4:20. Time when game ended: closing in on 1:30 AM. Saves blown by Mets: two — one by Pete Schourek, another by John Franco. Homers hit by Mets: four — one apiece by Murray, Jeff Kent, Todd Hundley and, before the rains came, Jeromy Burnitz, the rookie’s first as a major leaguer. Not only did the Mets win this game, it kicked off their first winning streak since the middle of April. It was a two-game winning streak in the middle of April and a two-game winning streak at the end of June, but when you’re bracketing a stretch of 15-48, you don’t have to be Crash Davis to know you don’t [bleep] with a winning streak.

In the midst of the madness of June 29, specifically in that seven-run seventh that gave the Marlins an 8-6 lead, Chuck Carr singled home Greg Briley to cut the Mets’ edge to 6-2. Carr had to leave the game after straining a rib cage. That meant by the time Dave Telgheder came out of the Mets bullpen to pitch the tenth, eleventh and twelfth, Carr was not playing. I mention this because either the morning after this game or maybe the morning after the game that followed, Telgheder was a guest on WFAN. I was definitely interested in hearing what he had to say. Dave had been up for a couple of weeks at that point. He’d started one of those Monday Met wins and earned the W. He finished the Tarp Game and rose to 2-0. As far as I was concerned, Dave Telgheder at 2-0 was the 1993 equivalent of Ken MacKenzie.

I remember exactly one thing Dave Telgheder said to whoever was interviewing him. I remember the gist of it, at any rate. The conversation was upbeat, befitting the veritable coming out party for a rookie pitcher who was succeeding when most about him were doing the opposite. I don’t remember who was asking the questions, but I don’t think it was much more of an interrogation than “what did you like best about getting that win in that crazy game?”

According to my memory, Telgheder said something that included his delight at the Mets getting to “shut up little Chuckie Carr.” Dave laughed when he said it, but devilishly. For a more modern reference point, maybe you recall John Buck assuming pie duties from Justin Turner one postgame when Jordany Valdespin was being interviewed about his walkoff heroics in 2013. It wasn’t a gentle “yay, we won!” whipped cream smush in JV1’s face. It was “this is an excellent excuse to hit you who irritate your teammates hard in front of everybody and make it look celebratory.” As I try to reconstruct Telgheder’s tone and words in my head, that’s what it sounds like. Dave, who came up through the Met system, was kidding about Chuck, who came up through the Met system, so maybe it was all good-natured. Or, to borrow a phrase introduced by Al Franken about ten years later, maybe he was “kidding on the square”: kidding…but not kidding.

As I took this all in (which was better than taking in the pennant chances for a team almost 30 games out of first place before the season’s halfway through), I wondered what, exactly, was so bad about Chuck Carr? Was he notably yappy when he was on the Mets? He’d been here for so brief a time, that I can’t swear I’d formed a strong impression. In that way that I was absent from typing class the week we were taught how to type numbers without looking at the keyboard — and therefore I still have to look at the keyboard when I want to type numbers — I wasn’t intently watching the Mets the week Chuck Carr first joined the team. It was the last week of April 1990. I was in the process of moving into my first apartment and flying to Tampa for my fiancée’s college graduation, after which my first apartment would become our first apartment. Big doings in two people’s lives. Three if you count what Chuck Carr was up to.

The 1990 Mets didn’t roar to the sort of start traditionally expected of them. Keith Miller, one of the better utilitymen the franchise has ever employed, emerged out of lockout-shortened Spring Training as the starting center fielder. Notice I didn’t refer to Keith Miller as one of the better starting center fielders the Mets have ever employed. Keith was a stopgap. Then Keith was injured. The Mets weren’t loaded with center field depth. To fortify their ranks, they had to reach down to Double-A Jackson and promote by two levels speedster Chuck Carr. I read New York Mets Inside Pitch and listened to the Farm Report on Mets Extra enough to know Chuck Carr was a speedster. Carr stole 62 bases in 1988 when he was a Mariner minor leaguer, 47 more in 1989 once the Mets got him. If the Mets had a speedster running wild in their system, word rose to New York before the player with the fast feet did. We didn’t have that many speedsters. In the ’80s we’d had Mookie Wilson and Lenny Dykstra. This was the ’90s. They were gone.

Davey Johnson, still managing the Mets in the new decade, shed about as much light as possible on the coming of Carr: “My needs now are somebody who can pinch-run, play some defense. My center fielder [Miller] has a tight hammy, and we needed another outfielder. How much Carr plays or how long he’s here is uncertain at this point.”

Not quite a heralding befitting a prime prospect. Davey was just trying to keep together what turned out to be his last Mets team. Carr played one game for Johnson, a loss on April 28, before returning to Jackson. Center field at Shea would find its groove in short order, with Daryl Boston coming over from the White Sox to platoon with perennial fourth outfielder Mark Carreon, usually a corner man. By the time their skills meshed to create one steady center fielder within a potent lineup, the Davey Johnson era had morphed into Buddy Harrelson’s managerial tenure. Somewhere to the south of New York City, mostly at Jackson and a little at Tidewater, Chuck Carr continued to run. He stole 54 minor league bases to go with one that he nabbed during a swift August jaunt to Queens.

In 1991, the Mets decided a single speedy center fielder was exactly what they needed to start the season. Except it wasn’t Chuck Carr. It was Vince Coleman, signed to a four-year deal that isn’t primarily recalled for how it blocked the path of Chuck Carr, but it did that, too, one supposes. Carr was up and down with the Mets the year they stopped altogether contending. The game in which he was granted his first big league start, August 28, was also the game in which he notched his first career RBI (off T#m Gl@v!ne, no less) and the game in which he injured himself in the field while misjudging a fly ball. There’d be one more appearance about a month later. The Buddy Harrelson era was about to end. So, in Met terms, was the Chuck Carr era, such as it was. The Mets swapped him and the 28 bases he stole between Norfolk and New York in 76 games that summer to St. Louis for a Single-A reliever. Across three seasons, Carr stole 128 bases for Mets affiliates and two for the Mets.

Artificially turfed Busch Stadium had been traditionally friendlier terrain for outfielders whose game was defined by their speed. The brief glimpse the Cardinals gave Carr in September 1992 generated Chuck’s kind of results: 22 games, 10 steals — plus a two-run double off Jeff Innis in one of Carr’s first games back in the majors, his way of invoking Simple Minds. Don’t you forget about Chuckie. The franchise coalescing in Florida took note. The Cardinals exposed Carr in the expansion draft. The Marlins took him with their seventh pick. He was about to be an Original Fish.

Within two weeks of the birth of the Marlins, Chuck Carr established himself as every day center fielder and leadoff hitter. By the time the Mets showed up at Joe Robbie for the Tarp Game, Carr was proving the skills he’d hone in the minors could play in the majors. He had 28 steals, en route to an NL-leading 58. A member of a first-year club leading his league in something was something else. As towering as Frank Thomas’s 34 home runs soar in the annals of the 1962 Mets, they placed him only sixth in the National League.

From the perspective of nearly thirty years on, the NL’s Top Ten Stolen Base Leaders of 1993 grabs a Mets fan’s attention. Gregg Jefferies, who wasn’t known for a bag thievery in New York, placed fourth with 46 sacks swiped. Eric Young, Sr., finished seventh with 42 for Colorado (his namesake son would lead the league in that category as a half-season Rockie/half-season Met two decades later). Brett Butler, two years before the Mets would sign him four years too late, totaled 39 stolen bases for the Dodgers, good for ninth in the circuit. Dykstra, as part of his MVP runner-up portfolio for the pennant-winning Phillies, absconded with 37, tenth among NLers. And that guy the Mets thought would be their speedster supreme, Vince Coleman, stole 38 bases, or ninth-best sum in the league. Vince might have swiped more had his Met career not come to an inglorious end in late July after he staged his very own Fireworks Night in the Dodger Stadium parking lot.

Chuck Carr outstole them all. His 58 bases were as many as any Met had ever stolen to that point, matching Mookie’s total from 1982. Chuck was also the most thrown-out base stealer of 1993, caught 22 times. He didn’t walk much for a leadoff hitter, and his OPS, when measured by contemporary standards, doesn’t amount to numbers associated with a spectacularly effective offensive player. But this was 1993. It wasn’t so far removed from the ’70s and ’80s that a base stealer who played fairly spectacular center field defense couldn’t be appreciated on his own terms. Marlins fans (they existed before they didn’t) appreciated Carr plenty. Far from wishing someone “shut up little Chuckie Carr,” they voted the kid from Southern California their Most Popular Marlin after the club’s first year of existence. He rewarded their support by stealing another 32 bases in strike-truncated 1994 while leading the league in singles and continually flashing his trademark smile. Chuckie may have been derided by some peers for the perceived crimes of excessive chatter and personal aggrandizement, but the folks who gave their hearts to the game (and slid their dollars across the ticket window counter) at a juncture when the game was on the verge of walking out on them noticed when a player gave his heart right back to it and them. Chuck Carr didn’t scowl his way to 90 stolen bases over the course of his two best seasons. The Memories section of Carr’s Ultimate Mets Database page confirms that if a person outside the baseball industry crossed paths with Chuck Carr, they were highly likely to identify as a Chuck Carr fan.

Against Dave Telgheder’s recommendation, I maintained a slight fondness for Chuck Carr even as his Met affiliation faded from view. We know how Old Friends can be in their wrath toward the team that gave up on them, and indeed, Chuck Carr drove in more runs against the Mets than he did any opponent in a major league run that lasted through 1997. Then again, driving in runs wasn’t exactly Carr’s specialty, so I don’t think it did any harm to give Chuck a light hand when he’d be announced as part of the Marlin starting lineup at Shea. I’ve always tried to acknowledge the prodigal sons when they’re in for a visit, at least until their post-Met success erodes my lingering goodwill.

After Carr left the Marlins, I stopped keeping up with his doings. I didn’t realize, until I read his obituaries, how much injuries depleted his primary skill set as the ’90s wore on. I didn’t know that he pretty much talked himself out of Milwaukee in 1997, albeit in the stuff of an anecdote Ron Shelton has to wish he’d written. It seems Carr swung on two-and-oh against manager’s orders and popped up. When confronted, Carr reasoned, “That ain’t Chuckie’s game. Chuckie hacks on two-and-oh.” Chuckie also packs for his next stop after such an explanation. The good news for Carr was his next stop was playoff-bound Houston, for whom he would hit his only postseason homer, off John Smoltz in the ’97 NLDS.

Then, while I was too busy focusing on the late ’90s/early ’00s Mets to notice, Chuck Carr was out of Major League Baseball. But not out of baseball. Carr’s smile in games and toward fans was genuine. He loved the sport enough to keep working at it wherever he could. He went to China and played on the Mercuries Tigers with future Met Melvin Mora (thus making them Mercuries Mets). He played in the Atlantic League when independent ball in the Northeast was a fresh concept. One of his two indy seasons was as a Long Island Duck, reuniting with Harrelson as Buddy was getting his quackers off the ground. Chuck then took his talents to Italy and then finished up in the Arizona-Mexico League, a 35-year-old player-coach ten years removed from his stolen base crown. Had Chuck Carr’s career crested later, in this day and age, he might have been hailed on social media for his “swag”. Or his flair/bravado might have rubbed some teammates and opponents the wrong way anyway because big league baseball still has more John Buck than Jordany Valdespin at its stodgy core. Or as someone who could run a lot but not hit nearly as much, he might not have been handed more than a cup of coffee — to go.

But if Chuck Carr was the person he was all along, he probably would have kept on talking and kept on smiling and there’d have been a reason to keep on applauding. It’s never too late for a baseball fan to put two hands together for a baseball player who let you know how much he loved the game.

This was very nice. Timely and informative. And I enjoyed reading. Happy Thanksgiving!

Chuck Carr played for the Atlantic City Surf and the Long Island Ducks of the Atlantic League in 1999-2000 when I was an umpire there, and was always a happy, smiling presence who treated me with kindness and respect. Cancer sucks. May he rest in power and peace, and forever keep hacking at 2 and 0 pitches. Thanks for this sweet memorial, Greg.

Great piece. But I can’t shake the feeling that I’ll be the World’s Oldest Mets Fan the next time the Mets win a World Series.

Early ’90’s was when I was getting my career started so I missed a lot of Mets business during that time. And my career ended up being in Indiana which meant missing even more. Absolutely no memory of Chuckie Carr as a Met.

Great article. Loved the writing, especially the humor about that ’93 team I paid little attention to.

And something I never knew, “So did newly acquired Sammy Taylor and newly acquired catcher Harry Chiti. Chiti, while no Berra at or behind the plate, would become famous in a very Metsian manner a little later in 1962, returned to Cleveland when the Mets decided he wasn’t the receiver for them. The player to be named later turned out to be named the player named Chiti. This transaction went down in Originalist lore as Harry Chiti being traded for himself. Harry batted .195 and was never quoted on the subject of what to do when you come to a fork in the road (“take it” — Y. Berra), but his aftermath read as colorful.”

That is indeed so very Metsian.

When I (infrequently) think of a Hillman on the Mets, I think of Eric, who was mentioned in a recent FAFIF article as owning an unlikely Met career record. When Chuck Carr came up to the Mets, I was initially excited because I thought they had somehow landed Chuck Cary, then I saw I was off by a letter. And the Mets Frank Thomas, to me, will always be the other Frank Thomas, similar to the other Bob Gibson, the other Reggie Jackson (Al’s kid who played in the Mets system and never made the majors), the other Pedro Martinez (the Mets eventually got the “right” one also) as well as both Bob Millers, both Bobby Joneses, both Sandy Alomars, and both Shawn and Sean Green.

Mistaken identity is one of the more charming weirdnesses of Metsiana. In any case, thanks for a fascinating article, and may both the deceased rest in peace. “Chuckie hacks on two-and-oh” deserves to be in the Baseball Quotes Hall of Fame, together with all the Stengelisms, Berra-isms and Satchelisms said and unsaid.