The Mets didn’t play ball in October, and I learned to be OK with that, despite dedicating my waking hours from late March through late September to their ultimately insufficient quest to play ball in October. Maturity being what it is, I grew distant enough from the grating, granular shortfalls of the 2025 season to allow that losing out on a playoff spot by a tiebreaker is sometimes just how the ball bounces (or gets lodged at the base of an outfield wall). Hence, I could go about my October not hung up on who was not playing ball, and enjoy a helluva lot who was, and, when there were no games in progress, just think and talk about other things.

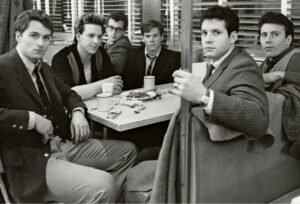

During a lull in the postseason, somewhere between the end of the ALCS and the beginning of the World Series, I got together at a nearby diner, as Long Islanders do, with the two friends I’ve known longer than anybody, not counting those with whom I share bloodlines. It would be simpler to say they’re my two oldest friends, but I’m a little older than each of them, and it would be just like me to point that out to them, not as a badge of personal longevity, but because of my fondness for exactitude. Had I mentioned that, it likely would have earned me a pair of stares before the conversation quickly pivoted somewhere else, probably toward that episode of Welcome Back, Kotter where Vinnie Barbarino murmurs, “gimme drugs, gimme drugs,” over and over to howls from the studio audience. However one sorted the technicalities of longest and oldest, it was an overdue meetup, as they all are at this stage in life, and like all our too-rare get-togethers, I couldn’t tell you what we talked about, exactly. Except John Travolta pretending to be a stoner (for Freddie “Boom Boom” Washington’s sake) on Kotter.

“When a woman asks a man — back from golf, the bar, a game — what he and his buddies talked about for the last four hours, the mumbled reply of ‘Nothing’ isn’t designed to drive her insane,” S.L. Price reasoned in his 2012 Vanity Fair retrospective on the enduring influence of Barry Levinson’s 1982 classic period piece Diner. “It was, indeed, four hours of ‘nothing’ which, for guys is…everything. It’s in what’s not said — the tone, the pauses.”

There was one pause I noticed when I groped to capture the contents of the afternoon for my wife, but mostly came up devoid of details, other than I ordered a Reuben with potato salad, and it came with fries, but the fries looked good, so I didn’t say anything to the waiter. I had paused my instinctual inclination to veer off into baseball and the Mets. One of the two guys at the table with me is a lifelong Mets fan, currently geographically displaced. His Amazin’ simpatico was my sports salvation through junior high and high school. The other isn’t into sports, but has been sympathetic to our cause these past many decades. Neither of them brought up the Mets, and I wasn’t tempted to, either. Other than a stray reference to some uniquely Canadian pennant fever I’d glimpsed after the Blue Jays clinching the American League flag the other night (fans ran into the street, but dispersed when the traffic light changed, which was apparently from a 2015 ALDS celebration but got reposted), and my recollection that the last time we were together was at Citi Field seven years ago, baseball didn’t as much as flicker within our rolling dialogue. My overriding obsession took a back seat to, well, nothing.

Just like in Diner, I suppose, except in real life, which, incidentally, is where I first saw the fictional Diner, with a group of friends that included at least one of these guys from lunch in October, maybe both; forgive the inexactitude forty-three years later. In a lovely cosmic coincidence, I’d had Diner sitting on the DVR from the last time TCM aired it. One night shortly after that late lunch with my friends, an evening when the 2025 World Series wasn’t showing, I rewatched Diner for the first time in ages.

“It still holds up” is an understatement. I wasn’t old enough upon Diner’s initial release to fully appreciate it, and I appreciated it plenty when I was nineteen. Most movies I’ve loved forever are like this, me not noticing that line wasn’t just a good line, it had something to do with something else from earlier in the movie, and it will come back around later to reveal something else. Or it’s an even better line than I realized the last time I rewatched this. Diner is as rewatchable as a rewatchable gets.

One thing, however, bugged me during this Diner rewatch. The throughline of this film set in Baltimore between Christmas Night and New Year’s Eve 1959 is the Colts. One of the guys at the diner, Eddie (Steve Guttenberg), is nuttier about the Colts than the rest of his pals. Eddie is so nutty about the Colts that he is going to make football knowledge a prerequisite of his upcoming nuptials — he’s finalized a comprehensive quiz for his fiancée to ensure she is indeed the right girl for him…or give himself an out in case he’s overcome by cold feet. The color scheme for the wedding, including the bridesmaids’ dresses, is blue and white. Most importantly, the gang will be getting together Sunday to go to the NFL championship game at Memorial Stadium. Everybody else agrees meeting at noon will suffice. Eddie insists on a quarter to twelve, because, you know, it’s the championship game.

One thing, however, bugged me during this Diner rewatch. The throughline of this film set in Baltimore between Christmas Night and New Year’s Eve 1959 is the Colts. One of the guys at the diner, Eddie (Steve Guttenberg), is nuttier about the Colts than the rest of his pals. Eddie is so nutty about the Colts that he is going to make football knowledge a prerequisite of his upcoming nuptials — he’s finalized a comprehensive quiz for his fiancée to ensure she is indeed the right girl for him…or give himself an out in case he’s overcome by cold feet. The color scheme for the wedding, including the bridesmaids’ dresses, is blue and white. Most importantly, the gang will be getting together Sunday to go to the NFL championship game at Memorial Stadium. Everybody else agrees meeting at noon will suffice. Eddie insists on a quarter to twelve, because, you know, it’s the championship game.

Exactly! Of course that’s how Eddie would think, because that’s exactly how I would think if the team I was craziest about in the world was about to play for the championship. You can’t take any chances, right? Except that scene from Diner came after many scenes in Diner when Eddie was doing other things besides concentrating on his beloved Baltimore Colts preparing to play for the National Football League championship. Barry Levinson may know his milieu like few directors have known theirs, but I’m sorry, there’s no way that if the Mets were in the World Series, I’d be calmly hanging out at the diner talking about sandwiches or Sinatra or anything but the Mets being in the World Series. If no one else wished to go over lineups with me, I’d be off in a room by myself pondering potential matchups. That would have been the case in October of 1982, just as it would have been the case in October of 2025. In fact, when our little group left the movie theater in the summer of ’82 — to head to a diner, naturally — the most quick-witted among us nodded in my direction and suggested, “Hey, let’s go to the Mets game!”

At the time, the Mets making a World Series was the stuff of cinematic fantasy, but yeah, “the game” is where my head would have been had the Mets of that era been the powerhouse that the Baltimore Colts had been in Diner’s. That’s where you indeed would have found my head in October of 1986, and October of 2000, and October of 2015. Priorities are priorities when a championship sits in your team’s grasp. Everything is different when your team is in it.

Just as it’s different when your team isn’t in it. You can go to the movies. You can go to the diner. You can think and talk about other things as well as nothing. You can also watch the ballgames your team isn’t in. Those can be classics, too.

No, Kevin, you were not. No Game Eight versus the Dodgers. No Game Nine. No games at all following Game Seven, the final satisfying course of a veritable Fall Classic feast, itself the last stage of an almost endless postseason bacchanalia of excitement and emotion blissfully free of ghost runners, even for those of us on the outside looking in. We should be filled up, yet we are never truly full when it comes to baseball. As the first utterly empty week of our lives in nearly three-quarters of a year has wound down, I’m not surprised I find myself continuing my emotional alliance with the likes of Gausman and, more widely, Blue Jays fans, regardless that I don’t know any. At my most directly invested, I’ve been Linus sitting on the curb beside Charlie Brown as Charlie Brown cries into the void, “Why couldn’t Kiner-Falefa have taken a secondary lead just two feet further?” I don’t know, Ontario version of Charlie Brown, but I feel ya and I hope, despite the outcome, that what transpired for Toronto across October of 2025 stays with you more as fun than torture.

I could have mentally aligned with the come-from-behind winners, but none of my internal affinity developed in the Dodgers’ direction. Respect and grudging admiration? Sure, why not? Of course the Dodgers are the world champions again. They’re the Dodgers. It’s been their world for a while. They might as well keep the title to confirm ownership. Preordainment didn’t demand they win it all, but the element of surprise has only so many tricks up its sleeve. The Dodgers embody abundance. There’s just so much of them. You get past the megastars, there are superstars. You get past the superstars, there are stars. You get past the stars, there are studs and stalwarts and substitutes who inevitably find a way to come through. You rarely get past all that, though if you do, you might bump into a living legend who is now consigned to the status of museum piece, except when he enters in the top of the twelfth to extricate his team from a bases-loaded jam. The instinct when the Dodgers come to work will always be to bet the over, even if it only seems like they always win.

Thirteen consecutive postseason appearances.

Gotta be more.

Five pennants in nine years.

Seems light.

Three of the past six world championships.

That’s it?

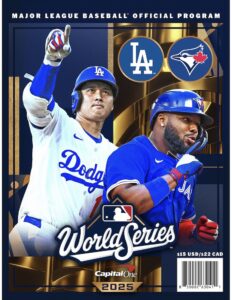

The most vital counting stat is the Los Angeles Dodgers of 2024 and 2025 are the most recent team to have won consecutive World Series, ensuring reflexive references to the team that repeated as world champion in 2000 will be reduced dramatically during future postseasons.

October is crammed with contemporary components that can shake out in any direction. Or they can just pour straight from of the sack in predictable fashion. Twelve teams go into the mix at September’s end. Eight have to play off to become four, with those four playing the four who sit and wait. From there, we have four, then two, then, at last, one. Anything can happen. It is designed so anything can happen, or so that fans can believe anything will happen. Two years ago, though it seems far more ancient now, the postseason process yielded the five-seed Texas Rangers defeating the six-seed Arizona Diamondbacks in baseball’s final round, concrete evidence that randomness can occasionally rule October.

This year, like last year, these Dodgers happened. When these Dodgers happen, apparently nothing can stand in their way.

Los Angeles, as if to present itself a challenge, accepted as roundabout a route as a 93-win team could receive. A Wild Card Series, in which they flicked the Reds — briefly occupying the presumed Met slot — aside in two games. Ceding all-important home field advantage for the rest of their run, L.A. strung along the Phillies until eliminating them in four during the National League Division Series (with Philadelphia assisting by essentially eliminating themselves at the conclusion of the final game), then whooshed by the senior circuit’s nominal top team, the Milwaukee Brewers, in a sweep. Each of those NLCS contests left behind a close score, but in the mind’s eye, it was a big blue stampede.

The series that decided the pennant was when I gave up on hating the Dodgers. I still don’t particularly care for them, mind you, but I had my Utley-stemmed animosity reduced to a shrug emoji. I liked the way the Dodgers pitched their way past the Brewers, which was with starters staying in as if that’s what their job description entailed. It was refreshing to experience, regardless of who was doing it.

The effort that pushed the Dodgers over the top, a predictable destination for a franchise whose logo could be a cornucopia, was that of Shohei Ohtani as pitcher and hitter in Game Four, the Friday night he struck out ten and homered thrice. When he accomplished all that, it was immediately and universally proclaimed the greatest game any individual had ever put forth. Truthfully, you couldn’t compare Ohtani’s crowning glory to anybody else’s, because what he did was incredibly incomparable. The only downside to it is any game when he doesn’t strike out ten while homering thrice — like that eighteen-inning night he got on base nine times (four times via intentional walk) but didn’t bother to pitch — is bound to come off as a mild disappointment. The Dodgers, when they peak, have all the starting pitchers, most of the hitters, momentum as a default setting, and drip relevant history. In Ohtani, they’ve combined the lot of it.

The shock-surprise quotient, in which one is shocked but not surprised, barely applies to Shohei. That he does everything he does is neither shocking nor surprising, never mind that nobody else does what he does. The Dodgers returning to the World Series was about as unsurprising as a postseason step could be. Yet when you delved into the details…nope, it was pretty much what you might have figured.

Would have one figured on the Blue Jays alighting to meet them? At the outset of the postseason, not necessarily. Who the hell knows what goes on over in the other league? Yet after the Jays did humanity a solid and dispatched the Yankees, they deserved closer consideration. As they clashed with Seattle, their possibilities were undeniable. For a spell, however, it was the Mariners’ year, much as it was the Brewers’ year when the year was no further along than August. Baseball years can be hot potatoes as they progress. The M’s had the Big Dumper and J-Rod and intoxicating charisma you hang a temporary hat on. The M’s had that cheek that had never been kissed by a date in the World Series. The M’s withstood a fifteen-inning breathholding contest versus Detroit just to advance to the ALCS, back when fifteen innings seemed like a lot. The wind was at the back of the Mariners clear to the nights it reversed course inside Rogers Centre, and suddenly, it was the streets of downtown Toronto, rather than the streets of Seattle, filled with revelers.

Would have one figured on the Blue Jays alighting to meet them? At the outset of the postseason, not necessarily. Who the hell knows what goes on over in the other league? Yet after the Jays did humanity a solid and dispatched the Yankees, they deserved closer consideration. As they clashed with Seattle, their possibilities were undeniable. For a spell, however, it was the Mariners’ year, much as it was the Brewers’ year when the year was no further along than August. Baseball years can be hot potatoes as they progress. The M’s had the Big Dumper and J-Rod and intoxicating charisma you hang a temporary hat on. The M’s had that cheek that had never been kissed by a date in the World Series. The M’s withstood a fifteen-inning breathholding contest versus Detroit just to advance to the ALCS, back when fifteen innings seemed like a lot. The wind was at the back of the Mariners clear to the nights it reversed course inside Rogers Centre, and suddenly, it was the streets of downtown Toronto, rather than the streets of Seattle, filled with revelers.

So we who dutifully tune into every World Series, even the Metless iterations, acquainted ourselves with the gamers, grinders, and second-generation Guerrero of the Jays, and we attempted to tease new storylines from their presence. The intensity of their extended moment in the postseason spotlight was so great that it took until Game Six, specifically the closeups of the outfield wall in Toronto when that ball got stuck at its base and morphed into a ground rule double, for me to recall where I knew that smoky blue with the powder blue trimming fence from. That was the fence Francisco Lindor homered beyond in September of 2024, that matinee when he broke up Bowden Francis’s no-hit bid in the top of the ninth of a game we absolutely had to have. From repeated viewings of Mets Classics, I’d recognize its distinct color scheme anywhere, yet I was so immersed in the Jays for the Jays’ sake, that the Mets of recent vintage had barely infiltrated my thoughts.

Flushing expats currently nesting north of the border needed to be processed on their newly Canadian terms. Chris Bassitt was now a gritty middle reliever rather than the starter who anchored our rotation for the bulk of 2022 until his shortcomings against Atlanta and San Diego weighed us down and helped sink us. Max Scherzer was back to being a citizen of October, not the ferocious fussbudget who engineered an escape from Queens in 2023. Andrés Giménez had long gotten used to hitting with runners in scoring position and with people in the stands, the latter of which he didn’t have the opportunity to do when he debuted with us amid the mandatory emptiness of 2020. I knew they’d been Mets once (just as I vaguely remembered backup catcher Tyler Heineman spending two months as a Paper Met in a the offseason spanning ’23 and ’24), but I didn’t see Metsiness in this World Series…save for a couple of AARRGGHH!!-inducing baserunning mishaps.

The Mets were a distant memory by the time this Series got going. Fine. I didn’t need to hear about them, not even in national-broadcast asides regarding our stars. Walks were worked out on full counts, and nobody invoked Juan Soto. Home runs went for long rides, and they weren’t deemed like something off the bat of Pete Alonso. By Game Three — the overnighter at Dodger Stadium that could have as easily played out in a clockless casino — the chat was limited to the actual participants. The Mets didn’t matter any less than the Mariners and the Brewers. Nothing mattered but the Dodgers and the Blue Jays. Give me a World Series that’s a World Series like this World Series, and eventually nothing else exists, just the two combatants and the prize for which they are vying down to the last heartbreaking swing. My first seven-game World Series was Pirates-Orioles in 1971. I was eight years old. I understood it transcended my standard parochial concerns. I rooted for the Pirates for a week like I’d usually rooted for the Mets. It helps to pick a side. The Orioles, like the Dodgers of now, were a little too familiar. I didn’t know the line about familiarity breeding contempt when I was eight, but I intrinsically got it.

The Dodgers were always going to represent the team we knew in this World Series. The Jays took on the role of the fresh face. Not as fresh as the Mariners would have been to the biggest stage, but fresh enough. Their World Series experience from 1992 and 1993 wasn’t salient to their modern-day endeavors except that the image of Joe Carter touching ’em all (he’d never hit a bigger home run in his life) remained accessible in our collective subconscious. Understanding Toronto had captured a pair of Big Ones in living memory — and noticing that Toronto is a large city and the Blue Jays have a large payroll — reduced the temptation to cast the AL champs as the scruffy upstarts in all this…even if against the Dodgers, almost anybody would be.

At the core of the World Series, we had the team that took out the Phillies versus the team that eliminated the Yankees. We were already blessed, regardless of outcome.

If you engaged with it, especially if you stayed awake for the marathon portions of it, this World Series evaded easy narratives. Once a handle was had on it, the handle grew slippery. When the Jays took a three-two lead, I read an article positing that if not of Yoshinobu Yamamoto throwing a complete game in Game Two and Ohtani producing so much offense in Game Three, the Series might be over. Uh-huh. And had the Jays kept missing their team bus, the Dodgers would have swept. There was no need to rush to conclusions. At various points, this World Series clearly belonged to the Dodgers, the Blue Jays, the Dodgers, the Blue Jays, and back and forth several times per night. I’d like to think the World Series belonged to everybody.

The Commissioner’s Trophy wound up in the Dodgers’ hands, once they prevented Games Six and Seven from landing in the Blue Jays’ mitts, with the Jays doing just enough to not wrap it within. The end result left me in mind of the 1975 World Series, when I rooted hard for the Red Sox, who fell to the Reds, and I couldn’t argue that the Reds hadn’t earned it, but I swore both teams not only could have won it, but should have won it. The 1982 World Series between the Brewers and Cardinals returned to my consciousness, too, probably because it followed the same trajectory of one team winning Games One, Four, and Five, and the other team (the one I was rooting against) winning Games Two, Three, Six, and Seven. Nobody in the 2025 World Series ever trailed by two games. No stubborn the home/road team has won every game pattern emerged. It always felt up for grabs. It felt, in some intangible manner, like a real World Series, the way snowstorms when you were a kid remain the snowstorms you still remember deeply. I don’t need two feet piling up outside in the months ahead. I’ll always take seven games to decide the world championship. In the wake of what we just experienced, all those World Series that went four, five (except for 1969, of course), or six games suddenly seem inauthentic. After seven games, particularly seven games like 2025’s, my inclination would be to give everybody a parade, sanction everybody to hoist nothing less than a WE WERE PART OF SOMETHING SPECIAL banner. One winner coronated, perhaps, but no losers detected. Hosannas all around.

My pro-Jays lean wasn’t as anti-Dodgers as I would have suspected. Maybe for the first time I truly understood why impressionable youngsters through the ages have gravitated to the overbearingly dynastic. The team you attach yourself to is relentlessly impressive, and rolling in their retinue becomes as rewarding as it is easy. Unwillingly witnessing what the Yankees were doing under Joe Torre in 1998 made me think this must be what it was like when Joe McCarthy was pushing buttons in 1938, or when Casey Stengel’s doublespeak c. 1958 was merely a sideshow rather than his main event. The Dodgers of Dave Roberts are in that territory. I can totally understand if soulless children, presuming baseball is on that demographic’s radar, gravitate to this franchise. The Dodgers have the biggest names. The Dodgers win a lot. If you came along within the past two years, the Dodgers win all the time. If you watched only this World Series, they never lost a razor-close game.

Like the 1960 Pirates, the 2025 Dodgers were outscored overall across seven games. Like the 1960 Pirates (Hal Smith and Bill Mazeroski), the 2025 Dodgers made hay out of a pair of home runs (Max Muncy and Miguel Rojas) hit in the eighth and ninth innings of the seventh game…then topped all that with an eleventh-inning home run (Will Smith) to capture the lead they never surrendered. The 1960 Pirates were a historic underdog, to Stengel’s last Yankees team. The 2025 Dodgers were the personification of an overcat, but didn’t scat when they were compelled to make comebacks. It helps to have resources. It’s even better when you can put them to good use.

The Dodgers always seem to know what they’re doing and how to do it. Then they do it. No wonder Steve Cohen five years ago mentioned wanting the Mets to grow up to be just like them within what were then the next five years. Hasn’t happened yet. Next year, perhaps. Always next year. Always perhaps. You can’t ask for more in November.

I am reasonably certain this postseason is unique and completely without precedent for me. I did not watch any part of any game. Not a pitch or AB or anything. The way the Mets’ season went down completely soured me on any thought of the game. IOW I now have a new least favorite season – though 1977 is so special that maybe it’s actually second.

My goals for the postseason were, 1) Don’t let the Phillies win and 2) don’t let the Yankees win. So in an abstract sense it should have been relatively satisfying even if we didn’t have the Seattle-Milwaukee series I’d have preferred. But my apathy continues and it’s possible this lasts until pitchers and catchers report next February.

My first 7 Game WS was 1973, when I was 8, and that was the first season I kept up with the Mets all season. I learned about the 1972 7 gamer from the 1973 baseball cards.

All in all, this (probably) has to be the most exciting WS of all time. If the 1973 Mets did not leave 72 men on base, surely that one would have qualified.

I love baseball, so I’m always going to watch the World Series, because all too soon after, baseball goes into hibernation.

So the fact that there’s no ghost runner in the postseason clearly shows that MLB knows it’s a stupid rule at best, and at worst, simply not baseball. If it’s not in the postseason, then it shouldn’t be in the regular season either.

We were on vacation far away out of the US but still watched most of the WS. Nice that the teams who vanquished evil made it.

After Game 5 I encountered a bunch of jubilant Jays fans. We chatted for awhile and I said “Good for you guys, this has been great so far!” The guy I was talking to, fueled by beer and happiness, prematurely pronounced “It’s about time! We haven’t won since 1993! That’s insane!!” Uh oh.

A. It ain’t over yet, Bub.

B. 1993? Ha!

I felt bad for him a few night later.

My standard reply whenever anyone says anything about how well the Mets are doing is an immediate “please don’t ever say stuff like that out loud.”

Cal was robbed.

The question that bugged me more and more as the playoffs got deeper and the Blue Jays made it further, all the way to a 9th inning lead and the winning run on 1st base in the 11th inning of World Series Game 7, is why is Trey Yesavage so good for Toronto but Jonah Tong was so inconsistent and not ready for us?

The two are about the same age, same fast track ‘helium rise’ trajectory through the minors, same level prospect, with even a cosmetic similarity in pitching style. Yesavage was called up ‘prematurely’ like Tong to fill the same critical rotation hole as Tong did for a scuffling contender. Yet for all their similarities, Yesavage delivered on his promise for the Blue Jays, all the way to the World Series, while Tong fell far short of virtually the same promise. If Tong had just been 1 game better than he was, the Mets get in and maybe flip a switch in the wildcard round.

By the end of the 2025 postseason, Yesavage versus Tong summed up my mystified frustration and disappointment over the 2025 Mets.