The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2015 3:22 pm What can I tell you that you don’t already know?

You know the Mets are the champions of the National League Eastern Division. They won that title Saturday and they maintained that title Sunday and as regards 2015, it is theirs forever. Even the NCAA can’t take it away. Every time I start to think about something else, the Mets having won the division is all I can think of.

You know the Mets won Sunday in their first outing as the reigning champions of the National League East. They swept the Reds by deploying a classic Day After lineup. Although the Mets still have some home-field advantage business to tend to, you have to go with the Day After lineup. It’s one of baseball’s finest traditions. You rest everybody who did the most to get you the crown and send their understudies to play in their place. The understudies for a division champion can’t be too bad. They’re champions, too.

You know (if you pay attention to these things) the Mets held rookie hazing day after finishing off the Reds. This time they dressed the kids in adult-sized Underoos and paraded them through the streets of Cincinnati. Last year it was skimpy superhero outfits. The year before they constituted a blushing bridal party. Once again, everybody smiled, everybody laughed. Everybody smiles and laughs even when there’s no division title in the bouquet, so this time it must have really been giddy. Hazing of the new guys strikes me as one of baseball’s least fine traditions, but if everybody’s having a sincerely good time (and the too-often present homophobia and misogyny inherent in this ritual is as toned down as possible), then, you know, boys will be boys…I guess.

You know the boys in Washington are screwed, especially the fella they brought in to close games who instead symbolically shoveled dirt on their season. In an episode worthy of the 1993 Mets, Jonathan Papelbon choked Bryce Harper in the Nationals dugout Sunday. All one can say to that sentence, let alone image, is “Wow.” Vince Coleman would have thought Papelbon’s behavior was unprofessional. Harper’s misdeed was not running full-bore after popping up. He should have run harder. Everybody should run harder on popups. Phil Mushnick could tell you that. But there are ways to communicate that without hands lunging for the neck of your teammate/prospective league MVP. Papelbon — who defending N.L. Manager of the Year Matt Williams sent back out to pitch after he assaulted his franchise player — makes no one around him better and everyone around him bitter. Washington’s acquisition of him may have been the Met move of the trading deadline.

I didn’t get into blogging to tell you what you already know (though I don’t mind repeating the part about the Mets as champs and Papelbon as chump). So here’s something I’m gonna bet the vast, vast majority of you don’t know. I didn’t know it until yesterday, and — at the risk of sounding immodest — if I didn’t know it, chances are it’s not widely known.

But Seth Wittner knows it and tells it.

Seth is a Faith and Fear reader who wrote to us in the aftermath of Saturday night’s clinching with an agenda. He wants to promote “Loo-Doo” as Lucas Duda’s nickname. So do Seth a favor and spread that around if you like it.

But never mind Loo-Doo, because Seth embedded another couple of autobiographical notes into his e-mail:

1) He’s been a Mets fan since 1962, when he was 12.

2) He lived in Elmont, near where American Pharoah would someday become a champion, and schlepped via trains to the Polo Grounds to cheer on a nag of a ballclub that was years away from sniffing the floral side of a finish line. “Lots of tears back then,” he says of that Mets outfit that finished 60½ lengths out of first that first year. Lots of loyalty, too, given that Seth’s still with our Mets all these years later.

3) He and a friend entered the very first Banner Night contest at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and earned second place, the prize for which was “four box seats to the first game ever at the Big Shea”.

Whoa, I said. Due respect to Loo-Doo, you gotta tell me what your banner said. It must’ve been a Loo-Doozy if it could win you such a phenomenal bounty.

Seth wrote back and filled me in on the banner and then some.

“Our banner had a silver trumpet on a solid black background. It said, ‘Ta-ta-ta-Da-da-da!’ as in ‘Charge!’ Beneath the words, we had the music for that snippet of melody a trumpet would play.

“My friends and I used to make lots of banners and take them to the PG. A few times, photos of our banners made it into Newsday.

“Here’s a story you’ll enjoy. Leon Janney was a semi-retired Broadway actor who played a bartender for TV commercials between innings. He would interview players or their wives. Everyone was bringing banners cheering on guys like Mays or Frank Thomas or whoever. Mike and I made one that said ‘Let’s Go Leon Janney!’ It had a picture of a sudsy, overflowing mug of beer.

“We were sitting in the right field upper deck. I felt someone tap me on the shoulder. It was Leon! He walked all the way from his season box behind the plate to where we were and talked baseball with us for a few innings. He mailed us autographed headshots and invited us (while he sat with us) to come watch a Rheingold Inn taping…but he never told us where or when.”

I know from Rheingold. We all know from Rheingold, the dry beer, the beer synonymous with the early years of New York Mets baseball. But the Rheingold Inn? Leon Janney? A bartender for TV commercials between innings who would interview players or their wives?

Did the Mets have a Steve Gelbs in 1962? A one-man Branden and Alexa?

I did not know. So I looked Janney up to see if I could find out anything else. The following I learned from a book called Cue the Elephants, written in 2005 by Dean Alexander, a memoir of 50 years spent working in television.

There was a “permanent, full-sized, functioning tavern” constructed in a studio at Videotape Center in Manhattan. It was dubbed the Rheingold Rest (Rest…Inn…close enough). Alexander worked there and saw “hundreds of Rheingold beer commercials” shot there. He likened the set, with its mahogany and brass and Cheers-like feel, to a “forerunner of the modern sports bar”.

In the middle of the action was Janney — a former child star, whose credits included a turn in one of the Our Gang comedies — as a barkeep, “who casually chatted with stage, screen, sports and political personalities who just ‘happened’ to drop by.” Alexander namechecks Tony Randall, Phil Silvers and Jim Backus among the visitors, adding, “virtually every living athlete who had ever played in New York made a pilgrimage to ‘Rheingold Rest’.”

According to Bill Shannon’s Biographical Dictionary of New York Sports, the Rheingold Rest aired after Mets games on Channel 9 those first two seasons at the Polo Grounds. Whereas Choo Choo Coleman became famous in part due to Ralph Kiner’s tale of Choo Choo coming on his postgame show and being legendarily taciturn…

“Choo Choo, what’s your wife’s name and what’s she like?”

“Her name’s Mrs. Coleman, bub, and she likes me.”

…Mike Tennenbaum, a contributor to the Ultimate Mets Database’s Memories section, recalled hearing Mrs. Coleman herself on Rheingold Rest. Leon, apparently, got more out of Mrs. C than Mr. K got out of her husband. “She met Clarence at the public tennis courts in Orlando, Fla.,” Mike wrote. “She recalled this soft-spoken master of the understatement as a wonderful tennis player.”

A self-described “beer reviewer, historian and raconteur” named Dan Hodge reported Janney’s skills went beyond interviewing. On the Rheingold Rest, Leon could be seen “illustrating tricky plays with the imaginative use of bottle caps as bases and baserunners”. Surely that made the sponsor happy (even if the tricky plays probably related to the sponsor’s team running into outs or throwing balls away).

Maybe not everybody was a fan. In 2010, someone on a Brooklyn Dodgers message board brought up the Rheingold Rest only to judge it “more like the Rheingold Snooze”. Nevertheless, the harsh critic of the program had fairly nice things to say about the host: “I met Leon on the subway once after a Mets game in the Polo Grounds, and he was a very nice guy, but he didn’t seem to know too much about baseball.”

Neither did the Mets, based on their records in ’62 and ’63, but we loved them then and we love them now and it’s characters like Leon Janney, whether they stood the test of time or only cross your consciousness because somebody brings them up in the service of disseminating a nickname for the guy who just blasted a grand slam in the current season’s division-clincher, are all part of the Amazin’ tableau.

So thank you, Seth Wittner, first runner-up in the 1963 Banner Night procession, for telling me something I didn’t know about the Mets. Thank you, Leon Janney (1917–1980), for taking note of the banner in your honor and schlepping up from your nice box seat to say hi to Seth and his friend Mike, not to mention your kind conversations with the man who would play Felix Unger, the lady who had married Choo Choo Coleman and the guy on the subway who wasn’t easily impressed.

And thank you, Sandy Alderson, for not trading for Jonathan Papelbon.

by Greg Prince on 27 September 2015 11:00 am  There have been 17 champagne celebrations for team accomplishments in New York Mets history. This is a scene from the 17th. Indulge me, Mets fans who weren’t viewers of Mad Men, as I channel Don Draper delivering — à la Matt Harvey on Saturday in Cincinnati — the most impressive pitching we had ever seen from him. The product, in this case, is a glorious new iteration of what our baseball team is capable of producing.

It’s not called the Collapse. It’s called a Division Title. It lets us travel the way a champion travels. Onward and upward, and higher again…to a place where we know we have clinched.

For those of you unfamiliar with what is being played off of above, Don, the master ad man, was branding, on the fly, the Carousel, Eastman Kodak’s contraption designed to show off your boring family pictures (long before Facebook usurped that function). The company executives who were Sterling Cooper’s clients had tentatively labeled their invention the Wheel. Don, however, saw something different in what they were selling.

And now you, the consumer of all things Mets, are seeing something different in the team with which you so closely identify. You’ve been used to a situation where you weren’t so much certain something was going to go wrong as you were sure nothing would ever go right again.

You’ve just learned the Mets have other, better applications.

My allegiance to the New York Mets dates back to late in the Mad Men era, to 1969, when everything went right, and 1970, when markedly fewer things worked out. After those two personally seminal seasons, I got that the Mets didn’t always win it all, but understood just as well that wondrous achievements weren’t beyond their grasp. In case I thought the first glimpse I got in ’69 was a fluke, 1973 came along soon enough to reinforce how wonderful the Mets could be.

Later…much later, there was 1986 and 1988 and 1999 and 2000 and 2006, each of them spawning commemorative t-shirts and selling tickets to games not originally scheduled. They made sense to me. They were of a piece with knowing what I knew was possible. All those other years, when the Mets weren’t winning, those were the outliers in my estimation. I got used to not winning for long (long) stretches, but I didn’t take that as the way it was supposed to be, just the way it was.

I don’t play the generational card much, certainly not to hold what I have experienced over the heads of those who’ve lived through less. To me, you choose the Mets whenever you choose them and you’re one of us. You’re eligible for every Real Fan perk I have to offer. But coming down the stretch in 2015, I felt genuinely bad for Mets fans who hadn’t been immersed in all or most or even one of those seven playoff years. I felt genuinely bad for anybody who made — whether by choice or instinct — 2007 the organizing principle of his rooting life. I felt genuinely bad for anybody who couldn’t help himself from shouting “COLLAPSE!” in a crowded ballpark (or comments section).

That’s not who the Mets have to be. That’s not what the Mets have to be about.

And now you’ve seen it for yourself.

You have the 2015 Mets. You have one of the 17 celebrations in Mets history. Seventeen times the Mets have opened bottles of champagne and poured them over one another. Seventeen times the Mets have won something transcendent as a team. Eight times it’s been entry to the playoffs. Six times it’s been a division title.

This time was one of each of those times. When Jay Bruce took his place in the procession behind Joe Torre, Glenn Beckert, Chico Walker, Lance Parrish, Dmitri Young, Keith Lockhart and Josh Willingham and made the final out of a Mets clincher against Jeurys Familia (following in the footsteps of Gary Gentry, Tug McGraw, Dwight Gooden, Ron Darling, Al Leiter, Armando Benitez and Billy Wagner), this was no longer a team that lets us down. This became a team that lifts us up.

Actually, it’s been a team lifting us up most of the past six months, dating back to those initial unbeatable April days, through the pitching-powered grittiness of June and July and then making like a dynamo once August hit with the full force of a revamped roster. Nevertheless, it had to be official to feel official. You had to know that the Mets could not just take a lead and build a lead but that they could keep a lead.

You know it now, baby. You know these are your National League East champions, the sole denizens of first place from August 3 to eternity where 2015 is concerned. You saw it on TV, you heard it on the radio, you followed it on the Internet and you can buy it at Modell’s.

You needed proof. I understand. We all need proof. Though it’s been obscured by the mists of time, there was a time I couldn’t believe a seemingly qualified Mets team could make it from September to October unscathed. In 1998, the Mets lost their last five games to ooze away from a winnable Wild Card. That was tough. In 1999, the significantly improved Mets lost seven in a row with two weeks to go and sent their fans and their fate into turmoil. That was tougher. As the Mets kept losing, I grew absolutely convinced the worst was inevitable. Neither the backstories of ’69 and ’73 nor the last-ditch rallies from ’86’s two Game Sixes could penetrate my consciousness. They choked last year, they’re gonna choke this year. That was my jam.

As you may know, the 1999 Mets got their act together on the final weekend of the regular season and, like the 2015 Mets, punched their ticket to the playoffs in Cincinnati. Before they could win that all-or-nothing showdown versus the Reds sixteen years ago, they had to beat the Pirates on the last day at Shea, which of course they did. That was the Melvin Mora Game, the one the Mets took when Mora scored the decisive run on a ninth-inning wild pitch. It was and remains my most cherished memory as a fan. The Mets had to do what they had to do and they did it. It wasn’t always going to be 1998. On the best of days, it could be 1999.

I watched that game in Loge alongside my friend Richie, who was kind of the baseball big brother I never had. We’re still in occasional touch via e-mail, but 1999 was really our year. Some years are like that, where you’re closer than ever to a particular person with whom you share a common interest. For Richie and me, it was the Mets and 1999. When Brad Clontz’s bases-loaded pitch thoroughly eluded Joe Oliver’s mitt and Mora raced home to give the Mets a season-lengthening 2-1 triumph and all 50,000 of us on hand went nuts, Richie had the presence of mind to grab me and stage-whisper over the din into my ear, “They didn’t choke.” It was exactly what I needed to hear.

To you who didn’t necessarily believe, I do for you what Richie did for me, albeit in the vernacular that overtook our consciousness following the unfortunate proceedings of September 2007.

They didn’t collapse.

I hope you heard that over the roar of the crowd. They didn’t collapse. They didn’t come close to collapsing. I didn’t think it was even an issue, considering they never led by fewer than four games from August 20 forward. I didn’t think anything needed to be said beyond “way to go,” considering the run the Mets went on between July 31 and September 14, playing 42 games and winning 31 times. Those were 1986-, 1988-type numbers. Those were being posted in the heat of what we called a pennant race, what I knew in my heart by late August was closer to a prohibitive runaway than a potential collapse.

A collapse wasn’t going to happen. And it didn’t. And it’s great. It’s great because we’re all Mets fans and it’s great because we’re all Mets fans who’ve experienced something like this now. I don’t have to dig deep and hark back. All I have to do is point to the standings and that lower-case “y” most outlets use to denote divisional champ. Links to video footage of the 17th champagne celebration in New York Mets history are fresh and plentiful as well.

You may still be tasting the literal and figurative bubbly from Saturday night. You may need to splash some cold water on your face. But if I could advise anything beyond, “they didn’t collapse,” it would be take how you felt in the moment after Familia fanned Bruce and put it somewhere where it will stay pristine. I don’t mean so you can take it out in the dead of winter or in some season down the road that doesn’t necessarily encompass a clinching. I mean, yeah sure, that too, but more immediately, I mean in case the rest of 2015 doesn’t match our fondest dreams.

I’m not suggesting this year won’t be the year. Heavens no, not while we are busy being N.L. East champions for the first time in nine years (or a million, in Met years). Alas, though, it’s worth noting that elsewhere on this continent, there are Cubs fans and Blue Jays fans and Royals fans and Pirates fans and some other fans who are convinced that this year is gonna be the year, based on the simple fact that their year has already been extended into the next month, just like ours has.

It’s a natural reaction. Just as bad results beget bad vibes, good results imply even better ones lie directly ahead. Last year at this time, there were 10 teams whose fans were feeling pretty, pretty good about their impending October appointments. In a matter of weeks, two; then six; then eight; and ultimately nine flocks felt significantly less good about the circumstances that had befallen the objects of their affection.

We are one of ten lucky batches of sumbitches. We have, at base, a 10% probability of winning the World Series. We can parlay that into 100%. Or we might crap out when pitted against another of the 10-percenters. Sadly, we can’t all be destiny’s children clear into November. If we don’t taste champagne again (let alone again and again and again) this year, I ask that you make a point of circling back to September 26 and remembering the night we did as your signature moment of 2015. Remember fiercely the 17th celebration in the event that the 18th, 19th and 20th don’t transpire exceedingly soon.

Remember 2006? What do you remember? If you say “Beltran looking at strike three” or words to that effect, I say reconsider. Remember beating the Dodgers in the NLDS. Remember beating the Marlins to clinch the East. Those touched off Celebrations Nos. 15 and 16. You see how long it took us to get to 17. As Monty Python might have put it, every celebration is sacred.

Don’t be that fan who, when presented a memory of anything that isn’t airtight success, says, “Don’t remind me.” You’re reading the wrong blog if that’s how you take your Mets. I make it my business to remind you of what our team has done, sometimes to make a larger point, sometimes just for the hell of it. But I don’t do it to make you feel bad or worse. When I invoke 1988, it’s not about Scioscia; it’s about 100 wins and a division crown. When I invoke 2000, it’s not about losing the World Series; it’s about winning a Wild Card, a Division Series and a pennant. When I invoke 2006, it’s not about one pitch that wasn’t swung at; it was about the most fun year I ever had blogging…until this one, which is just about as much fun to date.

Someday I will bring up 2015, the division title, the Saturday Duda and Granderson and Wright went deep and Harvey stayed in longer than anticipated and Familia finished up to clinch it. Regardless of what comes next, that — and everything that led to that — happened. It was beautiful. It will always be beautiful. Don’t let the course of Metsian events as yet unknown squeeze the context out of what you’re enjoying now and deserve to enjoy forever.

I’ll tell you one thing that has made 2015 unique among Met years that have included at least one champagne celebration, at least for me. You won’t find it in the standings, it doesn’t show up in a box score and I defy anyone who thinks it can be solved by deploying advanced metrics. The answer is all over whatever device you’re reading this on.

I got to enjoy this run toward glory with you. With you who visit this blog; with you who drop us a line via e-mail; with you who Like us like crazy on Facebook; and with you who I have the pleasure of tweeting back and forth with between every other pitch on what is sometimes derisively dismissed as #MetsTwitter. I don’t get the derision and dismissiveness, by the way.

• You know who composes #MetsTwitter? Mets fans who use Twitter to communicate their Mets thoughts to other Mets fans.

• You know who puts down #MetsTwitter? Mets fans who use Twitter to communicate their Mets thoughts to other Mets fans.

• You know who uses Twitter to communicate their Mets thoughts to other Mets fans? #MetsTwitter.

To paraphrase one of my favorite lines from the movie The Commitments, “Isn’t everybody on #MetsTwitter an arsehole? Except for management, that is.”

Anyway, when you’re a Mets fan online, you’re never by yourself. Nor would you choose to be. Taking in these Mets and what they’ve done alongside you — whether you always believed; you never believed; you didn’t believe until you had to believe; or you are unwittingly the embodiment of a human weathervane — has placed me comfortably inside a packed and jubilant stadium for every game. When we get a night that uncorks the best of our emotions, the celebrations we watch from the field and the clubhouse are more than matched by the joie de Uribe we engage in among each other. I swear the sensation is more real than virtual, whether or not you opted to pour champagne on your own home turf.

Which we Princes did, once the Jeurys-rigged ninth inning was completed and Stephanie and I emerged from our traditional post-clinch clench. We didn’t exactly don goggles and spritz Moet & Chandon around our living room and onto our cats. We laid in only enough to toast and sip, and that we took care of in a state of serene satisfaction. Unfortunately, I had a pre-existing headache that the surfeit of tweeting and the modicum of imbibing probably exacerbated a bit. I realized we hadn’t had anything substantive for dinner, which couldn’t have been helping, so I placed an order with a nearby pizzeria that operates under an agreeable enough family name and told them I’d come pick my order soon.

When the time came, I grabbed my Superstripe-model Mets cap (it’s my favorite), proudly affixed it to my slightly aching head and stepped out into the cool September night. It was the kind of move I made just as easily, pizza or otherwise, in the early autumn of 2006 and 2000 and 1999 and 1988 and 1986 and 1973 and 1969. It was 2015, which by now had something permanently in common with all of those aforementioned banner years.

It was a year when being a Mets fan once more felt exactly the way it’s supposed to feel.

And after I picked up the pizza? I spent the rest of the night talking Mets — present and past — with the good folks of the Rising Apple Report, which you can and should listen to here.

by Jason Fry on 27 September 2015 12:46 am

It’s not a new story any more. In fact it’s a well-worn tale on its way to becoming a cliche. It’s not a new story any more. In fact it’s a well-worn tale on its way to becoming a cliche.

But that’s the fate of stories that resonate with people, that mean something. And this one does. It’s the one I keep coming back to. And it’s worth hearing again.

It’s the story of Wilmer Flores, sent away to Milwaukee with Zack Wheeler for Carlos Gomez. In theory, it was a trade designed to make everybody happy. Gomez would come back to his first team, a rambunctious colt grown into a high-wattage hitter and charismatic clubhouse figure. Wheeler would return next summer knowing that his new team had valued him enough to acquire him long months before he could again be useful. And Flores would escape a situation that had become frankly dysfunctional.

He wouldn’t have to keep learning to play a position he’d once been told to stop playing, with his every hesitation and mistake exposed in public and excoriated at top volume. He wouldn’t be asked, while already doing something extremely difficult, to also add muscle to a sick, sputtering offense. Instead of being expected to speed up a transformation into something he’d never been, he’d be accepted for just being Wilmer Flores.

Plenty of athletes would have jumped at the chance. But Wilmer Flores didn’t want to go. Despite everything that had happened, he wanted to stay with the professional family he’d been a part of since he was literally a child. Distraught and dismayed, he spent his final moments as a New York Met in tears — an ordeal that was public, just like the previous ones.

And then came a twist that would have made even a soap-opera fan incredulous. The done deal was undone. Forty-eight hours later, the Mets faced off against the Nationals, the kings of the N.L. East, with Flores at shortstop. In the 12th inning, with the game knotted at 1-1, he drove a ball into the Party City deck. With a horde of teammates awaiting him at home plate, Flores tossed his helmet away and then grabbed at his uniform, at the script word on his chest, the one that turned out to have meant as much to him as it has to us: METS.

That all happened the same crazy week of the season that saw the great-pitch, zero-hit 2015 Mets 1.0 rebooted as Mets 2.0. There was the arrival of Michael Conforto from Double-A, viewed with reflexive suspicion as a low-cost PR gesture. There was the import of Juan Uribe and Kelly Johnson and Tyler Clippard, battle-scarred veterans and baseball professionals. And there was the shocking acquisition of Yoenis Cespedes, Plan C after deals for Gomez and Jay Bruce failed to materialize.

All of those events fueled the Mets’ astonishing rocket ride past the Nationals, a trajectory that has now reached escape velocity. But it was Flores’s resurrection that was the heart of it — the story we’ll remember, and tell in an effort to make sense of two months in which the impossible became routine.

For a long time we’ve labored under the burden of bad stories. There were the twin collapses that taught us to fear things that go bump in the September night, and then the financial reversals that taught us to assume we were being lied to on December mornings. The Mets, still shell-shocked from back-to-back disasters at Shea, moved into a modern park just in time for a savage economic downturn and the revelation that the coffers were bare. Both they and we took up residence at Citi Field like squatters in an stripped and abandoned palace, sniping about obstructed views and Dodger shrines, watching terrible baseball and listening to worse excuses.

We were a dumpster fire, a pitiable farce, a national joke. The athletes paid to be Mets failed and were discarded or succeeded and were subtracted anyway, sometimes exiting with an anonymous knife in the back. They left if they could, most of them; we stayed because we had no choice, we were born to this and it was too late to choose otherwise. And so for six years we subsisted on the little we had. There was nostalgia, correctly diagnosed by Don DeLillo as a product of dissatisfaction and rage. There was the ragamuffin insistence that glasses were 1/10th full. And there was hope — wild and desperate hope, idiotic and indomitable hope. Hope, a bucket constantly filling with water even as it runs out the massive hole blown in the bottom.

But those bad stories have lost their power over us. They dissipated into phantoms a little after 7 tonight, exorcised by Matt Harvey and Lucas Duda and David Wright and Jeurys Familia. We’ve rediscovered that September can be wonderful, and repopulated our dreams with memories that will make us laugh and clap and shed a happy tear come winter.

Like Matt Harvey explaining why this time he wasn’t going to let go of the ball, his face hard but his voice cracking.

Like Daniel Murphy and Jon Niese, two of just four remaining Mets who wore orange and blue at Shea, beaming at their children, who looked amazed at finding themselves scooped up in their fathers’ sodden, sticky arms.

Like the conga line of Mets slapping hands with fans who’d made the trek to Cincinnati and camped out behind the visitor’s dugout, waiting with their banners to salute and be saluted.

Like Cespedes in his custom goggles (as if he’d wear any other kind), standing with a cigar in his mouth next to Bartolo Colon, as imperturbable and Zen with a champagne bottle in his hand as he is with a ball out on the mound.

Like Wright, older and wiser than the last time he saw a magic number hit zero — and so appreciating the moment even more.

Like the joy on the face of Terry Collins, who spent four and a half years stoically explaining why a perpetually undermanned team wasn’t winning, then awoke one day to find he’d been handed a real one — a team he’ll now take to his first-ever postseason.

Like you, wherever you were, whether it was Cincinnati or your favorite bar or your lucky spot on the couch. In the top of the ninth I realized we had no champagne in the fridge and so hustled two blocks to the store. I got back for the bottom of the inning, and when Familia fanned Jay Bruce I sank onto my back on the carpet — a collapse born of joy instead of pain.

These are all good stories we get to tell ourselves now. And next time things threaten to go awry, next time we doubt or despair, we’ll remember that disaster isn’t the only thing that can take you by surprise.

Because sometimes the dutiful, decent captain whose career seems in jeopardy actually returns from the disabled list — and launches a massive home run on the first pitch he sees.

Because sometimes that kid called up from Double-A as a glimpse of the future turns out to be the present, and you realize he’s here to stay.

Because sometimes the big bat you want gets away, and the next big bat you want gets away, but the third time really is the charm, and you find yourself wondering if you too would be better at everything if you wore a parakeet-colored compression sleeve.

Because sometimes the late-season showdown with your biggest rivals, the one you’d been dreading, yields three straight come-from-behind victories, including one in which a 7-1 deficit in the top of the seventh turns out to be no big deal.

And because sometimes the accidental shortstop you get saddled with turns out to be the heart of the team — the one whose reaction to cruelties and misfortunes is to want to stay and help write a better story. And then sometimes, given an unlikely second chance, he does just that.

October is an undiscovered country. The Mets may win 11 more games after their normal course of 162 or they may win none; their season may continue into November or be a memory before the kids have picked out their costumes.

But whatever happens in the postseason, they’ve already won. And so have we. All of those games are bonuses, extras, lagniappe — a stolen season snatched back from winter. They’re our reward for nearly a decade of crazy perseverance, for getting up when it seemed a lot smarter to stay down, for insisting — in the face of considerable evidence to the contrary — that ya gotta believe.

The magic number is zero. The ball’s over the fence. Doubt and despair are walking off the field with their heads down. Come on around to where we’re waiting to greet you with open arms.

Welcome home.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2015 1:50 am A Nationals loss cut it from three to two. A powerful Mets win — Syndergaard, Duda and Granderson at the forefront — sliced it from two to one. That’s where the magic number stands now. With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, the Mets will have officially qualified for the postseason.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, it occurs to me that the October routine to which I have hewed for the past eight autumns will be altered significantly.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t be writing that post that puts in perspective how long the Mets have waited — and are still waiting — to make the playoffs again.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t be seeking new ways to compare the Mets’ ongoing playoff drought to those of other teams that haven’t won anything in a very long time.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t be going to the well of the same seven previous Met postseasons to draw parallels to what’s going on in yet another Metless postseason.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t have to attempt to cheer myself/us up by gratuitously referencing something that happened in October of 1969, 1973, 1986, 1988, 1999, 2000 or 2006.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t have to temporarily align myself with or against some team I don’t give a fig about the rest of the year.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t feel compelled to weave a tenuous Mets angle to make whatever I’m writing about some non-Mets playoff team quasi-relevant to a Mets readership.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t lose a large percentage of my sense of purpose once the regular season is over.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t be treating the postseason as I imagine a heroin addict treats methadone.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t be continually monitoring my interest level in October baseball and either wondering why it’s not greater or marveling that it’s as great as it is.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t have any idea what’s going in one NLDS and two ALDSes.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t have to frame winter’s spiritual arrival quite so soon.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, I won’t soon mention 2007 or 2008 except incidentally.

With one more Mets win or one more Nats loss, what I will do is…

Well, I can’t say for sure, but I sure look forward to finding out.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2015 9:15 am The fine folks of Steak ‘n’ Shake, a restaurant chain I’ve been known to patronize with a little too much enthusiasm for my optimal well-being, use as their slogan the phrase, “In Sight It Must Be Right.” Although its backstory has something to do with letting the customers see the meat that’s about to be turned into their sumptuous Steakburgers, the implication is if you are tooling about this great nation of ours, or perhaps just strolling down Broadway in the vicinity of the Ed Sullivan Theater, and you see a Steak ‘n’ Shake, then…bingo!

I can’t see a Steak ‘n’ Shake from where I sit, but I can see a division title up ahead in the ever decreasing distance. Why, it’s not very distant at all. The lights are on, the doors are open, the grill is hot. We’re gonna be inside any minute.

And man, it’s gonna be delicious.

The New York Mets, by way of the extraordinarily thoughtful Baltimore Orioles, lowered their magic number to 3 on Thursday. With more than a week to go, the Mets will have to win and/or the Nationals will have to lose a total of three games to make the sixth National League East championship and eighth playoff berth in Mets history a reality. The Mets lead their closest competitor by 7½ games with nine to go.

I am restating what you all know just to emphasize how in sight all of it is. It’s happening. It’s really happening.

The Orioles did more than their share of our dirty work over the past three days, sweeping their Beltway neighbors while the Mets napped Tuesday and Wednesday and bringing that number we can’t resist counting down from 7 to 4 — or Belanger to Weaver, in deference to who was doing the actual knocking off of digits for us. But the Mets woke up last evening and did a little whittling of their own, directly taking care of business in Cincinnati.

The top five men in the lineup all produced for what seemed like the first time in a long time; Steven Matz pitched adequately and hit effectively; and the bullpen didn’t break. Jeurys Familia recovered from his recent Freddie Freeman debacle (like you didn’t know one of those wasn’t going to come crashing down on us eventually) to move within one of Armando Benitez’s saves record. As countdowns go, it’s not the one that has our attention, but 42 saves compiled relatively quietly is a quality accomplishment.

Winning 6-4 en route to a magic number of 3 sets us up for something loud and joyous. We are in the driveway if not quite at the doorstep, but we have arrived close to where we need to be. It is real and it ought to be understood as spectacular.

We haven’t done this in nine years. Approximately 17% of my life has been lived since the last division-clinching. That’s a time frame that encompasses a September when our seemingly surefire Magic Number countdown stalled at Swoboda, a marker we dipped below last night. I’ve had it in the back of my mind (lately somewhere toward the front) that if — if — we got this one below 4, I would treat its conclusion as 4-gone.

Hence, I’m getting ready to get giddy. I’m warning our affiliates that when — when — it happens, I will brook no pessimism. Save it for the morning after the morning after. Save it for your NLDS anxieties. Those will be legitimate when they approach. But first this is in sight. I defy you to not enjoy it.

A hundred out of a hundred Mets fans instinctively thought “Bud Harrelson” when the last out was made in Cincinnati, and not just because you can’t watch the Reds without thinking of Pete Rose and you can’t think of Pete Rose without thinking of Buddy Harrelson taking a licking and keeping on ticking. Buddy is the quintessential 3 in Mets history; every other 3, from Gus Bell to Curtis Granderson would have to acknowledge his pipsqueaked primacy. But today I want to give a nod to a 3 who came and went in two seasons and left little legacy, except for two things I remember most of all.

Damion Easley was one of those veteran pickups who looked very good when he did something well and who looked deceptively decent when he wasn’t doing much of anything. I was always comforted by the presence of Damion Easley in the lineup or off the bench despite looking it up once and discovering that his Wins Above Replacement during his second of two years as a Met was negative. I couldn’t quite comprehend that. Damion Easley seemed to be one of those guys who made your team better. How could he be dragging it down?

I suppose on some meta-level he must have been, because no team that included Damion Easley ever made it to the postseason, including the eventually Swoboda-stalled Mets he came to in 2007 (though an injury curtailed his season long before any lead got away) and the star-crossed 2008 outfit that followed directly behind them. In the twilight of his 17-season career, it was mentioned regularly that no active player had played more games without making it to the playoffs than Easley. How brutally fitting in that context it was, then, that in the last of his 1,706 major league appearances, Easley’s team was eliminated from playoff contention. Those were the 2008 Mets, the unit to whom Damion’s WAR measured -0.5, implying that if not for the half-win he was taking away, the Mets would have…well, they would have come up a half-win short, wouldn’t have they?

So get off Damion Easley’s case. Besides, in Easley’s final plate appearance, pinch-hitting for rookie Bobby Parnell with two out and nobody on in the bottom of the ninth, the Mets trailing by two, he walked, making him Shea Stadium’s last baserunner and, once Ryan Church flied to Cameron Maybin, Shea Stadium’s last runner left on base. He went out by making one more lunge at a postseason that ultimately never accepted him.

I remember Damion holding the unwanted distinction of being the active leader in a category no player wants any part of, but I said I remember something else as well, and that’s this. When the ’08 Mets had commenced to rolling, Easley was an important part of the surge. There would have been no Game 162 heartbreak if not for the midseason uprising that briefly catapulted the underqualified Mets past the mighty Phillies. On the night in July when they won their seventh in a row (en route to ten straight and a 40-19 spree that carried them into September), Easley made all the difference, homering off the Rockies’ Taylor Buchholz in the eighth inning to give the Mets a 2-1 lead Billy Wagner would preserve in the ninth.

Frankly, I don’t remember the home run, but I do remember that Easley did something noteworthy in that particular game, because he was Kevin Burkhardt’s postgame guest that night, and a phrase he used in their interview has stuck with me to this day. He said the Mets weren’t just confident, but that they had “the earned confidence”. They felt good about themselves, Easley explained, because they had earned every right to feel that way.

We, my friends, can feel good, too. We can be confident. After a 153-game span during which our first-place team has definitively separated itself from the pack, we have earned it. We have in sight something Damion never got to glimpse up close. It is only right to revel in the feeling as we move even closer.

by Jason Fry on 24 September 2015 12:30 am The Mets’ slump has become a full-fledged rut, one of those stretches where a team seems suddenly incapable of doing any of the things it just recently did so well. Met hitters are expanding the strike zone and flailing their way through frantic at-bats, Met fielders are being alternately impetuous and butter-fingered, Met starters are faltering and Met relievers are getting pounded. A rut like this wouldn’t be fun to watch in early May, and it’s certainly not fun to watch in late September when we’re thinking about a different month and its promises and perils.

If you’re convinced you’re watching another collapse, well, I’ll try to be of some solace. The Mets are a mess right now, no doubt, but the Nationals are fighting not just them but also the math — and right now the math is the far tougher opponent. If that sounds snarky, it mostly isn’t — it’s just the reality of the last two weeks of a pennant race that’s dwindled to a handful of games. For the outcome to be different, the Nats have to be very close to perfect and the Mets have to be not just mostly terrible, like they were on this mercifully concluded homestead, but excruciatingly terrible.

Is it possible both those things will happen? The math says it is, so I won’t tell you it isn’t. But the Mets have to play even worse than they’re playing right now, and the Nats have to play a lot better than they have against Baltimore. We think we’re miserable, but while the Mets were watching another close one spiral out of control in the late innings on Wednesday night, the Nats had Matt Williams trying to destroy Max Scherzer‘s arm, Bryce Harper and Jayson Werth fanning on pitches they had no business swinging at, and Jonathan Papelbon throwing at Manny Machado‘s head in a game the Nats only trailed by one.

OK, you say, the math will let the Mets survive their own ineptitude, but they’ll limp into the playoffs and get steamrolled. Eh, not worth worrying about. October’s a new season. Plenty of teams have hit the postseason hot and fallen apart, just as plenty of teams have arrived looking rickety and wound up covered in confetti. (It’s dirty pool, but recall that the 2000 Yankees looked like impostors when they arrived at the World Series.)

If you accept that but hate “backing in” to a playoff berth, just stop. It’s been nine years without a postseason berth. I don’t care if the Mets perform an avert-your-eyes pratfall worthy of the bastard child of Jar Jar Binks and Buster Keaton so long as they get there.

And then we’ll see what happens.

Until then, hey, look at it this way — ruts and insane winning streaks both feel like they’ll last forever, but they never do. If you think baseball obeys both causality and moral virtue, the Mets have 10 games to figure out what’s wrong and fix it. If you think baseball is an entertaining, largely random sequence of discrete events, the Mets have 10 games to hope their luck reshuffles into something that will make us happier. Until then, hey, look at it this way — ruts and insane winning streaks both feel like they’ll last forever, but they never do. If you think baseball obeys both causality and moral virtue, the Mets have 10 games to figure out what’s wrong and fix it. If you think baseball is an entertaining, largely random sequence of discrete events, the Mets have 10 games to hope their luck reshuffles into something that will make us happier.

* * *

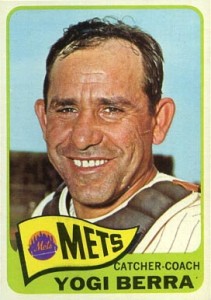

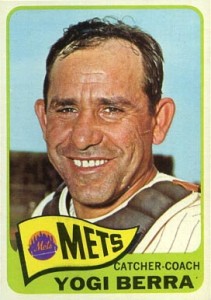

Greg did a superlative job paying tribute to Yogi Berra, so the best thing I can do is point you to his work from yesterday. But I’ll add a little bit from the perspective of a baseball-card dork.

You’re looking at Berra’s 1965 Topps card – his only one as a player for the Mets. (Those are Yankees pinstripes in the photo.)

To review, Yogi retired at the end of 1963, capping 18 seasons with the Yankees. He managed the Yankees in 1964, got fired despite taking the team to the World Series, and joined the Mets as a coach in the spring of ’65. He had eight at-bats during spring training, but agreed at the end of April to be added to the active roster for two weeks. That wasn’t an arbitrary timeframe — this was when teams carried 28 players for the first month of the season.

Yogi’s tenure as a Mets player consisted of nine at-bats over four games. He returned to duty with a pinch-hitting appearance on May 1, then collected two singles and caught nine innings as the Mets beat the Phillies, 2-1, on May 4. “Might be beginner’s luck,” he told reporters. (His first hit was a perfect introduction to life as a Met: It drove in Ed Kranepool, but Joe Christopher managed to get thrown out at third before Kranepool crossed the plate, erasing the run and what would have been Yogi’s 1,431st RBI.) He collected another at-bat the next day and then caught a full nine once more on May 9, the first game of a double-header against the Braves. Yogi struck out three times against Milwaukee’s Tony Cloninger. He was in pain and couldn’t get around on the fastball. On May 11, the eve of cut-down day, he quit. “I can’t do it no more,” he said.

Yogi’s time as a Mets player was a footnote to his playing career, one that I imagined seemed unnecessary then and definitely feels that way now … except it produced that card. And that’s a pretty good exception.

I mean, just look at it. It’s perfect. It’s a great baseball card and a great piece of Americana all in one.

Greg, Shannon Shark of MetsPolice and I talk a lot more about Yogi and his place in Mets history in the latest episode of I’d Just as Soon Kiss a Mookiee, the world’s best Mets-Star Wars podcast. You can listen in here.

by Greg Prince on 23 September 2015 10:55 am The first-place Mets, you might say, were lucky Tuesday night. True, they lost for the fifth time in seven games — 6-2 to the Braves — but they won a valuable square foot of real estate in their march toward the National League East title when the Nationals lost to the Orioles. Their magic number dwindled to 6, proving that being lucky on top of being (usually) good has its benefits.

Met luck isn’t always appreciated in the modern age, but once upon a time they were led to the precipice of the promised land by someone considered by his peers the luckiest man on the face of the earth…someone also considered one of the best to ever ply his craft.

Yogi Berra was legendarily lucky and unquestionably good. If you have that going for you, there’s not much that can go against you.

Berra — whose presence as a Met catcher, coach and manager for eleven seasons between 1965 and 1975 was so constant that it barely occurred to a kid reaching baseball consciousness in that period that he’d had anything to do with anybody else — passed away Tuesday night at 90. It was the last night of summer, but fall was already firmly in the air. The first thing I thought of when I heard the news this morning, what with the window open and a soft breeze brushing by, was that this is Yogi’s time of year. When others might be putting a wrap on their baseball seasons, Yogi’s was just getting going. He played, managed or coached in 23 postseasons, from his rookie year with the Yankees in 1947 to 1986, when he was the bench coach for the National League Western Division champion Astros. Nobody came to the plate more often in World Series competition and nobody recorded more hits. Nobody else guided a team from each league to the seventh game of the World Series.

As this autumn alights, each of the three franchises for whom Yogi Berra wore a uniform is well positioned to make it to the playoffs. It’s a fairly fitting tribute to how whatever he touched eventually turned to good.

Yogi Berra was a fall classic unto himself. And he wasn’t bad the rest of the year, either. Take April, for example. April 1972, to be specific. That was the month Yogi accepted his second managing job, taking the reins of our New York Mets. It was under the worst circumstances imaginable. The man he coached first base for, Gil Hodges, had just died young. It still stands as the most tragic episode in the history of the franchise. Gil was already a legend. Now he was a saint. There could be no tougher act to follow.

But Yogi followed it. “I don’t like the way the job came,” he would say later. “But I want to prove I can manage.”

He did so once before, after his Hall of Fame playing career with the Yankees wound down. He took over the 1964 club at the end of its dynastic run and led them to one pennant more than perhaps they were due. They were 5½ out with 38 to play, yet finished first. He got them to Game Seven against Bob Gibson and the Cardinals. For his troubles, he was fired.

The Mets swooped in and gave him a home. Yogi would coach (and briefly catch) for Casey Stengel. Casey gave way to Wes Westrum, who gave way to Salty Parker, who gave way to Gil Hodges, who brought about the miracle of 1969, with three trusted lieutenants from his Washington Senators days — Rube Walker, Joe Pignatano and Eddie Yost — plus Yogi. Always Yogi. A World Series was being played, a World Series was being won, there was Yogi, just as it had been almost without pause for the Yankees before the Yankees booted Berra out of the Bronx.

That worked out fine for us and fine for Yogi. He belonged to us from 1965 forward. He’d put on No. 8, he’d trot out to the first base box and good things would tend to happen. Many things went right in 1969. The luck of Yogi was not to be discounted. How lucky was Yogi?

He was the player who had already booked a later flight and thus wasn’t on board when the team plane was bounced like a basketball.

He was the customer who, during Spring Training, waited for his fellow coaches to pay for and pick up their laundry first and then, as he approached the cash register, discovered his receipt came printed with a star, denoting he was the establishment’s something-thousandth customer and therefore got his clothes back at no charge.

He was, as a teammate once put it, blessed with great luck to even out the grand scheme of things. As Phil Pepe related the theory in The Wit and Wisdom of Yogi Berra, “If God had to make somebody who looked like Yogi, the least he could do was make him lucky.”

Had he not been called to take on the impossible task of following Hodges, Yogi probably could have settled in for the long haul and remained a first-base box fixture at Shea Stadium. Instead, he put himself on the line. He would be the manager of the Mets, with all the pressure that implied. He inherited a ballclub that was supposed to win in 1972. His good humor would be tested. His likeability would be dented. It couldn’t help but be. It was his show.

Yogi brought the Mets out of the gate fast — 25 wins in 32 games. A team that could have been excused for grieving was playing its best ball since 1969. It’s a detail that seems to get glossed over when the quick start is recalled. The ’72 team was populated to a great extent by players who matured into major leaguers under Hodges. To this day, they speak reverentially of Gil in tones no player will likely ever summon for a manager again. Yet there they were, in the wake of losing Hodges, playing hard and winning for Yogi.

It had to be more than luck that was transpiring under those trying conditions. None other than Stengel had attested to the smarts and skills Berra brought to bear. “My assistant manager,” Casey called him when he caught so durably and dynamically for the Yankees. “I never play a game without my man.” In the decades to come, it would become fashionable to second-guess the Mets’ choice. They were clumsy in not waiting more than a couple of hours after Hodges’s funeral to name Berra as his successor and they were shortsighted in not giving serious consideration to their farm director (and another Stengel acolyte) Whitey Herzog. Perhaps. But Berra proved the right man to keep the franchise going at its darkest hour. In the rush to quote his most irresistible malapropisms, what he knew about baseball and how he applied it to a team that badly needed it shouldn’t be glossed over.

Once more to Mr. Stengel: “They say Yogi Berra is funny. Well, he has a lovely wife and family, a beautiful home, money in the bank and he plays golf with millionaires. What’s funny about that?” Casey might have mentioned the 358 home runs, the three MVPs, the fifteen All-Star selections, all of that World Series bling, the love and admiration of multiple generations and (though the Ol’ Perfesser had to watch it from the upper Upper Deck) the ability to draw a standing ovation from a Shea Stadium packed with Mets fans and Yankees fans who had been snarling at each other prior to the first pitch of the first interleague game between the two teams in 1998.

The first pitch was delivered by Yogi — in a Mets cap. Of course everybody rose and everybody cheered. Nobody snarled when Yogi Berra was in the house.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t much luck could do in the face of mounting injuries as 1972 got away from Yogi and the Mets. But the best of Berra was yet to come. Actually, the worst of mounting injuries was yet to come, too. The 1973 club was supposed to pick up where the 1972 club fell apart. Instead it crumbled further. After a decent enough start, the Mets dipped below .500 in late May and into last place in late June. For extended stretches, there was no Jerry Grote; no Bud Harrelson; no Cleon Jones. Not to mention there was absolutely no clue as to what was wrong with Tug McGraw.

Yet there was a glint of luck shining through. While the newspapers mulled over the possibility that the Mets would do what the Yankees had done nine years earlier and pin the blame on Berra — a possibility chairman of the board M. Donald Grant didn’t exactly discourage from being discussed — the Mets never fell so far into the basement that they fell out of the race. They were aided immeasurably by a division that was never definitively wrested from their theoretical grasp. But what a wild theory it was to think the Mets were still in it. A team in last place as summer churned down to its nub coming on to win a title seemed too fanciful a proposition for even those who bore witness to the miracle of ’69.

But Yogi had been there four years earlier and Yogi understood something everybody else was slow to comprehend.

On August 17, the manager examined the standings in the N.L. East. The Mets hadn’t been very good — 53-65, sixth place in a six-club circuit — but the deficit between them and the first-place Cardinals was a mere 7½ games. The gap had been larger at that stage of 1969, and the Mets had come back then.

So why not now?

“We’re not out of it, yet,” was Berra’s mantra into the middle of that August. “We can still do it.” It was more than a case of the You Gotta Believes in the manager’s mind. “Everybody in our division had some kind of streak except us, and I had my whole team back,” he said. “I felt if we could go on a little streak, we could make a move.”

Indeed, on August 17, Harrelson, Grote and Jones were penciled into the same starting lineup for the first time since August 1. By August 31, the whole team had begun to sharpen. They climbed out of last that day and into fourth on September 5. Two weeks later they were in the midst of the most remarkable journey any team has taken in any week in any September.

On the 18th, they beat the first-place Pirates and sat in fourth place, 2½ back.

On the 19th, they beat the first-place Pirates and reached third place, 1½ back.

On the 20th, they beat the first-place Pirates (the glorious Ball Off the Top of the Wall affair) and took second place, one half-game out.

On the 21st, they became the first-place Mets, beating the Pirates and taking a half-game lead.

Once Yogi’s crew was ensconced, they stayed ensconced. He had the regulars he wanted where he wanted them. Grote behind the plate, John Milner at first, Felix Millan at second, Harrelson at short, Wayne Garrett at third, Jones in left, a platoon of Don Hahn and Dave Schneck in center and Rusty Staub in right. Jones, Garrett and Staub were the hottest hitters on the planet. The pitching — Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, Jerry Koosman, George Stone forming the most formidable of rotations and a rejuvenated McGraw blowing minds and saving games out of the pen — yielded almost nothing.

Yogi Berra hadn’t panicked and Yogi Berra was proven a prophet. He let his players play and he watched his players win. First a division, then a pennant, then three games against the first club that could legitimately claim the dynasty tag since his old Yankees. Yes, he could’ve started Stone in Game Six at Oakland. Yes, he could’ve had a better-rested Seaver ready for Game Seven. Yes, he might’ve thought about sending Willie Mays up for one final at-bat when the Mets were barely holding on against the A’s. Mays was at the end of the line, but he had also been one of the handful of players in the history of baseball who had fashioned a more spectacular career than Berra. Yes, Yogi could have conceivably done a few things differently and maybe helped win the 1973 World Series for the New York Mets.

But no, nobody else got the 1973 New York Mets to the World Series and I don’t know that anybody else could have. We still relish that stretch drive. We still cherish the touchstone that is summed up so logically in his irrefutable statement that it ain’t over till it’s over. We still Believe in Mets team after Mets team because of that Mets team.

Yogi Berra was the manager. Lucky for us he was good at it.

by Jason Fry on 22 September 2015 2:56 am From our vantage point in the front rows of Citi Field’s third level. Emily, my father-in-law and I had a pretty good view of what was going on down there on the field during the first inning of Monday night’s game. We’d watched Jon Niese convince three Braves to play patty-cake with the infield, and now we were watching the Mets continue to frustrate us. Much as they had against the Yankees early in Sunday’s debacle, the Mets seemed determine to squeeze as little offense out of a good situation as possible.

Curtis Granderson had walked, continuing his remarkable transformation at an age when few baseball players are capable of changing their spots. Daniel Murphy had dropped a single into right, followed by a similarly soft hit from Yoenis Cespedes. But then Lucas Duda hit a ball basically straight up, which didn’t benefit anybody except Shelby Miller.

Up came Travis d’Arnaud, who hit a little bouncer to Adonis Garcia at third.

Garcia flipped it into Daniel Castro at second, with Cespedes bearing down on him, and then everything sputtered and got weird. The ball was lying on the infield, Granderson was across the plate, umpires were doing things, and then several Braves converged around a lone Met in camo and pinstripes.

I couldn’t figure out the specifics of what had happened down there, but the general issue was immediately clear: Murph had Murphed.

But this was a bizarre one even by the standards of our own lovable avatar of chaos. Up in the stands we all shrugged and muttered; that Murphy, whaddya gonna do? Down on the field, Murph gave his gear to Tim Teufel and slunk morosely around the infield like a dog who’d just been found surrounded by shredded throw pillows. Later, looking at the replay on SNY, I still couldn’t figure out what Murph thought he was doing. He couldn’t have assumed it was a double play, because he was (inexplicably) turned around between second and third watching what was happening behind him. He saw Castro hadn’t thrown to first … and wandered onto the infield grass anyway. Did he think Duda’s pop had been the second out?

Gary Cohen was so flummoxed he missed the play, which pretty much never happens, while Keith Hernandez just gave a little moan of despair at finding himself in such a pitiful fallen world.

In the top of the third, the relevant question wasn’t about Murph’s recent bout of Murphing, but whether Niese could avoid Niesing.

Niese had been rolling along, mixing his pitches so effectively that I considered the underwhelming Atlanta lineup and had That Thought, followed by noting to Emily’s dad that Niese was absolutely pouring in strikes.

Which he immediately and perversely stopped doing. Having retired the first eight Braves without so much as breathing hard, Niese threw four straight balls to Miller, hitting a Leiteresque .059 and nearing the end of a full campaign as a starting pitcher without a single RBI. He then gave up a hit to Michael Bourn, Castro was safe on Wilmer Flores‘s error, and up came Freddie Freeman with Niese stalking around the mound.

Stalking around the mound is a danger sign with Niese; it strongly suggests that he has lost his cool, which can soon be followed by his focus, which can soon be followed by whatever lead he’s been given, which can soon be followed by the game.

Freeman belted the first pitch, which knuckled in the air — and wound up in Cespedes’s glove.

Niese had tried to Niese, but been given a reprieve — which he took full advantage of. He started off the fourth by walking Garcia and surrendering a hit to the ageless A.J. Pierzynski, but then made a nifty grab on a Nick Swisher bouncer back to the mound, starting a double play. Starting the sixth, he made an even better play, sprinting to first as Duda collapsed on top of a Castro grounder and flung it to first for the out.

And Murph would be heard from again, as he so often is. He rammed a first-pitch double off Andrew McKirahan with nobody out in the seventh, the big hit the Mets have been missing for several days. That got the Murph-O-Meter back to neutral, wrapped up a 4-0 Mets win, and brought several hundred thousand Met fans in off their ledges, or at least convinced them to stop hanging their toes over the edge while screaming about T@m G1av!ne and Luis Ayala.

Not a bad night’s work, bouts of chaos notwithstanding.

by Jason Fry on 21 September 2015 12:15 am I love our apartment in Brooklyn, but it has one nasty design flaw: The downstairs plumbing can back up during torrential summer storms, turning the toilet and tub into geysers of dirty water until the city’s sewer system catches up with all the water falling out of the sky.

It’s gross, y’all.

As you might imagine, this has made me a bit edgy during bad weather. When I know potential trouble’s coming, I fire up the computer, monitor the radar map and start asking frantic questions. Is the water in the toilet starting to shimmy and shake? How hard is it raining? How long will this last? Do I get the pump ready? No? How about now?

Weather.com’s radar shows light rain as pale green; downpours that could do us harm show as red. But Weather.com only updates every five minutes, which is annoying when you’re a paranoid bathroom defender.

Another site, Weather Underground, updates every minute. Much better! But here’s the thing — Weather Underground’s color gradient is more … let’s say alarmist than Weather.com’s. Weather Underground’s red is the equivalent of Weather.com’s yellow, which is a level of rain I keep an eye on but not enough to be a problem. Weather Underground’s yellow is the same as Weather.com’s green, which is routine if-you’re-going-out-grab-an-umbrella stuff.

I’ve lived in this apartment for nearly two decades. I know how this works. But knowing it doesn’t help when I load Weather Underground during a summer storm and see a wall of red coming at Brooklyn.

My heart pounds.

My breath gets short.

Even though I know that the red I’m seeing is not actually red.

So Matt Harvey was pretty good for five innings. Then he left and the Mets commenced to play stupid, to quote a man who saw a lot of that. Daniel Murphy yakked up a ball he should have ate; David Wright made an error; Hansel Robles gave up a whole lot of runs. The back end of the bullpen then gave up a whole lot more. Meanwhile, the Mets weren’t hitting. They let a shaky-looking C.C. Sabathia off the hook in the first and never put him back on it.

As things cratered, there was a lot of bile directed at Scott Boras (I contributed my share on Twitter), which wasn’t really relevant considering what went wrong in the game, but at least made us feel a little better. And then there was the collective nervous breakdown one expected, which I tried not to contribute to but probably did anyway.

The radar looks red — the crimson of anger, of BLOOD, of DOOM. And my trying to tell you to flip over to the other, more sedately colored app showing the exact same weather isn’t going to help. Because we remember, and we react.

The Mets are not phoning it in or lacking cojones or choking or trying to kill us or anything like that. The problem is several talented members of the team are simultaneously not getting hits. This is an unfortunate confluence of unfortunate things that happens to baseball teams periodically. We — the poor blighters who live and die on the outcome of games we can’t affect — call this thing a slump. And then we desperately try to make that slump conform to our insistence that everything has a reason and is part of a larger story.

And, well, when we’re laboring under the collective memory of some bad shit, the story we tell ourselves is a tragic one.

I get it. I do it too. But check back at mid-week and we’ll see what the radar looks like, OK?

* * *

First the New York Times, now New York magazine! It’s a Faith and Fear media bonanza!

Thanks to longtime pal of mine and reader of the blog Will Leitch for his kind words. Here’s hoping Will has a reason to check in on us to get our dazed reaction to confetti and champagne. He’s familiar with our dazed reaction to less happy events.

by Greg Prince on 20 September 2015 10:35 am Saturday’s was one of those games in which you tend to focus on one key element that went awry until you realize the other key element never went anywhere and thus rendered the first key element’s awryness moot. Noah Syndergaard, Terry Collins said, threw two bad pitches. Your impulse will be to obsess on those two bad pitches, each of which were turned into home runs with a man or more on base. And you will, because they resulted in five runs allowed, and there’s no way you can ignore your talented starter surrendering five runs on two swings. You will search for a rationale. You will rue pitch selection and BABIP bloops and FIP fates. You will seek to dissect Syndergaard’s pair of shortcomings all the way from here to Denmark.

But you can’t ignore the other key element. The Mets didn’t hit a lick against Michael Pineda and the approximately 48 Yankees relievers who trudged in behind him at Joe Girardi’s hyperactive direction. Together, the 49 of them shut out the Mets, 5-0.

If Collins’s one big moment of managing — pinch-hitting Juan Uribe for Lucas Duda with the bases loaded and two out in the sixth when the Mets were already down by five — had paid off, yet the Mets still lost by, say, 5-3 or 5-4, the impulse probably would be to fret over the hitting. We’d feel reassured that Syndergaard pitched very well (6 IP, 8 SO, 0 BB) when he wasn’t making the two bad pitches (a fastball to Carlos Beltran, a sinker to Brian McCann).

But why couldn’t they get one more big hit?

Why couldn’t they bring one more runner home in a key situation?

Where is Yoenis Cespedes (0-for-17) and why have you replaced him with Folgers Crystals?

What is Kevin Long doing to stop this offensive shame spiral? Can we get Lamar Johnson back?

How about Dave Hudgens?

Yeah, hi Pete, you’ve got a great show, first time, long time, listen, I wanna know why Terry isn’t batting Cespedes ninth, they need to get Wally up here to read him the riot act and maybe overturn a few buffet tables, the guy’s a total bum.

None of that happened. Uribe struck out and Saturday’s bottom-of-the-inning paucity continued unabated. Nevertheless, the nagging feeling never left the pitching side.

It was pitching that carried the Mets through the Cespedesless portion of summer, back when everybody was going 0-for-17 and nobody batted an eyelash (though if Collins had batted an eyelash cleanup, it would have been an improvement over John Mayberry). It was pitching that provided the floor — keeping the Mets from ever falling more than 4½ back while waiting for the lumber-carrying cavalry to arrive — for an otherwise anemic attack. The pitchers executed Dan Warthen’s master plan of throwing “strikes when you have to” and “balls when you want to”. The starters as a unit made you feel like Dwight Gooden did in 1985. Gooden admitted to Tom Verducci in Sports Illustrated that when he was having his season of a lifetime, he quietly rooted for his teammates to get him a run or two and then make their outs already yet so he could go back to the mound. Three decades later, I understood the impulse. I only wanted to watch our pitchers. For that matter, the only Met hitters I wanted to watch were our pitchers.

Now? Nowadays, give or take an unheralded Marlin rookie or bulging Yankee battalion (Pineda, fine…but six relievers for fourteen outs with a five-run lead?), you figure the Mets are going to hit. There will be slumps, but slumps end. Even if slumps are slow to cease and desist, all it takes sometimes is one good inning of hitting to make everything better for your batters.

It’s never that simple for your pitchers, especially our pitchers. One bad inning of pitching makes everybody anxious. Two bad innings can quickly equal a loss. A loss fuels anxiety. The element you counted on to prevent or at least curtail losing is no longer a certainty. It’s not a matter of Syndergaard not matching Pineda on a given Saturday. It’s Syndergaard not matching Syndergaard from June or deGrom not measuring up to deGrom from July or Harvey…

Oy, Harvey, and all that implies.

Pitching is more than the backbone of a baseball team. It is the back discomfort of baseball. “When it comes to backs,” I never get tired of quoting Paulie Walnuts quoting a doctor friend of his, “nobody knows anything, really.” Nobody knows what good inning limits really do. Nobody knows how resilient anybody’s arm really is. Nobody really knows why there were Hall of Fame pitchers who took the ball every fifth (or fourth) day for a generation and rarely missed a start and nobody really knows why all the TLC in the world can’t divert a fresh, young gun from the DL let alone TJS.

What I don’t know is if the set of solutions the Mets are attempting to apply to their pitching questions will answer anything. Let’s skip a day. Let’s skip a start. Let’s skip Harvey into the clubhouse after five. Let’s leave it to Logan Verrett to make everything better. Logan Verrett filled in twice for Harvey. Logan Verrett will fill in for deGrom on Tuesday. Logan Verrett is this organization’s little blue pill. I hope they’re taking him as directed.

Goodness knows this staff is talented. If goodness knows anything else, I hope goodness will let us know ASAP. DeGrom looks tired. Syndergaard throws two bad pitches out of 88 and somehow gives up five runs. Harvey has a recurring case of the agent. Steven Matz isn’t the least bit grizzled. Jon Niese is excessively frazzled. Bartolo Colon is Bartolo Colon, which is usually great, except for those nights when it decidedly isn’t. Sharpness has been in short supply in general. Still, you’ve gotta trust that enough of these exceptionally talented fellows will sharpen in time for those moments when there won’t be time to work it through; or to rest them up; or to skip merrily along and let Logan do it.

For 148 games, it’s been a long season. You’d be inflicting harm only on yourself if you didn’t relax a little when everything didn’t go right. Those 148 were played to get us to the 14 games that remain and then (knock wood) an unknown quantity beyond. The known quantity that got us most of the way here was starting pitching. I wish I could know that it will be as sound as it was in the heat of summer the rest of the way. It is the lengths our starting pitching can go to that will likely determine how long our impending autumn will run.

In theory, relaxation is still advisable. In practice, good luck with that.

|

|

Until then, hey, look at it this way — ruts and insane winning streaks both feel like they’ll last forever, but they never do. If you think baseball obeys both causality and moral virtue, the Mets have 10 games to figure out what’s wrong and fix it. If you think baseball is an entertaining, largely random sequence of discrete events, the Mets have 10 games to hope their luck reshuffles into something that will make us happier.

Until then, hey, look at it this way — ruts and insane winning streaks both feel like they’ll last forever, but they never do. If you think baseball obeys both causality and moral virtue, the Mets have 10 games to figure out what’s wrong and fix it. If you think baseball is an entertaining, largely random sequence of discrete events, the Mets have 10 games to hope their luck reshuffles into something that will make us happier.