The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 11 May 2011 9:14 am The Mountain Time Zone and the mountainous rain delay combined to knock me out before the final pitch last night. Hung in there through Mets Yearbook: 1966 and Mets Yearbook: 1967 (which SNY cut away from just as Whitey Herzog was about to announce his intention to draft…what a cliffhanger!) and reveled, as Gary Cohen did, in the fact that it took two pitchers — Mike Pelfrey and Jason Isringhausen — and two batters — Dexter Fowler and Ryan Spilborghs — to complete the same plate appearance when play resumed because of the precipitation interruption and the rash of owwies that were taking down Mets and Rockies left and right. But I was growing very drowsy as their Paulino — Felipe — walked our Paulino — Ronny. And the last thing I remember was something about Willie Harris pinch-hitting.

At which point I assume I closed my eyes in the hopes that he wasn’t really still a Met.

Next thing I knew, it was later. My first thought upon stirring was, “Is it the bottom of the ninth yet? Is K-Rod on? Omigod, what has he done? Is it the fourteenth because he gave up the tying run in typically aggravating fashion?” My second thought was “Mets 4 Rockies 3,” because when my eyes were opened fully, the postgame show was on and the score was on the screen.

“Gosh,” I wondered in the seconds before I conked out again, “I wonder how difficult he made it.”

Color me delighted to have read the pitch-by-pitch transcripts this morning and discover that Frankie Rodriguez kept no one awake. He didn’t extend the game. He didn’t inject anxiety into the game. He didn’t subliminally boost sales for Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey, the stuff I noticed advertised over the right field fence where Rockie home runs traveled earlier in the game. As far as I know, he didn’t react to anyone after the game the way he did when the sight of Colorado uniforms (or something) enraged him last August. Rodriguez just went out there, pitched the inning he was signed to pitch, pitched it cleanly and steered the Mets to the clubhouse with a win for all and a save for him.

Big-money free agent joins club and (eventually) performs as intended on consistent basis. Or as the headlines never seem to read, SOMETHING DOESN’T GO WRONG FOR METS.

Because of the creative contract to which the Mets signed Rodriguez, schoolkids no longer automatically associate “55” with Orel Hershiser, Shawn Estes or Chris Young (though Young’s shoulder will likely render him a well-meaning footnote in most Met textbooks). Frankie needs to finish 55 games this season — be the last Met to throw a pitch in just over a third of the scheduled contests — to have an option kick in that will allow him to serve as Mayor of Moneyville for another year. When he was Francisco Rodriguez, expensive, plea-bargaining, unreliable head case, this was cause for shudder. Now that he’s something like the K-Rod of American League legend again…still expensive but relatively reliable and no longer noticeably menacing society…I’d suggest taking an eye off his appearance clock.

Ideally, I’d rather the Mets not be on the hook for seventy-bajillion dollars in 2012 ($17.5 million, technically), but the clause is there and through no unfault of his own, Rodriguez is living up to his part of the bargain. The Mets occasionally take leads to ninth or maybe eighth innings; Terry Collins calls on Frankie; Frankie delivers the goods; Terry’s confidence grows; Frankie gets more calls.

He’s doing what he’s supposed to be doing. He’s also not doing what he’s not supposed to be doing away from the mound. I wouldn’t have blamed the Mets had they figured out a clever way to jettison his contract altogether after he attacked his girlfriend’s father last summer, but the Mets aren’t nearly clever enough to pull something like that off, so he’s here. What’s more, he’s presumably followed his proscribed course for good behavior. If we are to believe in redemption, then we have to believe that anger management programs might actually work.

Francisco Rodriguez will inevitably blow another game as the Mets closer. I wouldn’t be surprised if he blows his top, too, hopefully in a manner that harms neither human beings nor innocent animals. No doubt the guy is suspect, partly for a few too many ninth innings that went awry (in the tradition of all the other closers in whom we’ve misplaced faith for the past twenty years), mostly for what we learned about him in the wake of his temper overtaking him. If he slips in either way, we’re not going to be patient, more for Mets fan reasons than humanitarian ones, but in the meantime, he’s walked the straight and narrow off the field and he hasn’t given away much on it.

And unless we turn back time to when a quality start meant consistently going nine, somebody’s going to have to close games the rest of 2011 and into 2012. If the Mets want to be innovators and figure a better way to do it than automatically handing the ball to the same pitcher every time they’re ahead by three runs or fewer, fine. But until then, we have somebody who’s among the best in baseball at his particular core competency…and we don’t have many of those. We might as well get some use out of him.

As far as the $17.5 million fourth year for a reliever who was losing something off his fastball when we signed him…well, thanks Omar. But I’m disgusted enough that the Mets are likely positioning themselves as a small-market team — and not necessarily a good one — that I don’t want to hear about the need to shed gobs of salary to keep them afloat. Get the minority partner in here and act like a New York team. You don’t have to throw the multimegamillion-dollar deals around to impress us, but making it your priority to “unload” your better performers because you “can’t” re-sign them…it’s patently unacceptable. I don’t want to accept it. If you can honestly plot a trade of Francisco Rodriguez (or some other player whose name keeps coming up in this context but I don’t want to mention because I don’t want to think about him in terms of his not being a Met) to better the team in the long term without shooting it in the foot in the near term, you have my blessing. But nix to M. Donald Redux if it gets to that point.

If it’s late September and the Mets are long out of it and Rodriguez is sitting on 52, 53 appearances, I understand sending for a car and wishing him well as he leaves for the airport. If we’re long out of it with little hope of getting back into it right away, maybe a high-priced closer isn’t a priority (though ninth innings are still ninth innings, whatever the price). But if we’re in position to win games across the balance of this season, and there’s no better answer at the other end of the phone when Dan Warthen calls Jon Debus, then in the name of legitimacy, get Frankie up.

I may even sleep more soundly if we do.

by Greg Prince on 10 May 2011 12:43 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 31st game in any Mets season, the “best” 32nd game in any Mets season, the “best” 33rd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 031: May 16, 1983 — Mets 11 PIRATES 4

(Mets All-Time Game 031 Record: 27-24; Mets 1983 Record: 11-20)

There weren’t many people at Three Rivers Stadium this 44-degree Monday night. Maybe most Pittsburghers were home watching the Motown 25 special on NBC. It drew 47 million viewers, most of them, presumably, attracted by the appearance of the biggest star in the land in the spring of 1983, Michael Jackson. Jackson didn’t disappoint, revealing his moonwalk to a nationwide audience that had yet to think of the former Jackson 5 star as Tito’s, Jermaine’s, Jackie’s and Marlon’s brother from another planet.

Thus, it was left to a mere 1,970 to attend the Mets-Pirates game — an unscheduled makeup of a rainout the day before — and watch the first big move made by another performer emerging as a superstar in May 1983. It wasn’t going to do the broadly ignored home team much good, but for the visitors and anyone watching back on Channel 9 in New York, his development was going to be a thriller.

Darryl Strawberry had been up with the big club a week-and-a-half. His elevation was rushed by the reckoning of some, with his previously deemed necessary Triple-A seasoning curtailed to 71 plate appearances, yet it didn’t come a minute too soon considering the Mets were 6-15 when the SOS was flashed south to Tidewater. In the five-game losing streak that preceded Strawberry’s promotion, the Mets scored eleven runs; for their last three games, in which they were swept at home by Houston, they drew 15,719 paying customers.

No, it didn’t seem too soon whatsoever for 21-year-old Darryl Strawberry. Mets fans had been waiting for him since June 3, 1980, the day of the amateur draft when the Mets, by virtue of their abysmal 1979, held the first pick in the nation. Strawberry’s name — and who could forget a name like Strawberry? — first floated into the greater consciousness in Spring Training, when Sports Illustrated’s baseball preview issue (the one with Cardinal batting champ Keith Hernandez on the cover) intimated the long, lanky, lefthanded slugger was another Ted Williams waiting to happen. The 15,719 diehards who filed into a desolate Shea across three spiritless midweek nights, along with the millions of would-be attendees who were staying away from the stadium in droves, were all waiting after six lean years for anything to happen.

The next Ted Williams would do nicely in the imaginations of a superstar-starved fan base. The Mets attracted 15,916 for his debut, which may not sound like many, but it outgated the entire Astro series.

The first pitcher the underripe Strawberry saw was tough Reds righty Mario Soto, who struck him out. No shame in that. Soto struck out twelve Mets on May 6 and held them to one hit — a pinch-homer by Danny Heep, the player whose spot in right Darryl was usurping — until the ninth, when reigning Met power threat Dave Kingman took him deep with one on and two out to send Darryl’s first game into extra innings. Come the eleventh, the young/black/next Ted Williams (he was described as all three) nearly carved his signature in Shea’s concrete when he launched a fly ball that appeared en route to breaking a 4-4 tie and the Mets’ losing streak: both the five-game skid and the six-year horror show. Oohs and aahs followed its flight, perhaps into instant history.

“When I hit it,” the rookie said afterwards, “I thought it had a chance to be fair, but then I saw it hooking.”

It curved foul and Darryl Strawberry had to settle for his first major league walk. In the bottom of the thirteenth, he’d walk again, steal for the first time and be on second when George Foster ended the evening on a three-run home run off Frank Pastore. Darryl Strawberry scored the winning run, capping a pretty decent debut.

Only thing the kid forgot to do on his first night in the majors was hit. He went 0-for-4 that Friday night and struck out three times. Same thing the next day, a Met loss. Now the unreal comparisons were shifting from Ted Williams to Willie Mays, though not just because of talent. Willie, it was recalled, came up to the New York Giants 32 years earlier (also in May) and didn’t get a hit in his first dozen at-bats. In that regard, Darryl beat Mays to a taste of success by one AB. After an 0-for-11 start to his major league career, Strawberry singled off Cincinnati righthander Rich Gale.

His batting average soared to .083.

Now the question turned to when would Darryl Strawberry hit his first big league home run. Mays’s first hit was, in fact, a circuit clout — off the Boston Braves’ Warren Spahn — in his thirteenth at-bat and his fourth game. Ted Williams’s inaugural blast came in his fourth game, too, his fourteenth at-bat overall. Darryl Strawberry, who’d whetted every Mets fan’s appetite by belting 34 homers and swiping 45 bases at Double-A Jackson in 1982, had some catching up to do if he was going to be an immediate legend.

Manager George Bamberger, a rather uncelebrated rookie pitcher for the very same 1951 Giants Mays joined, recognized too much hype when he saw it, even as he was penciling his overmatched phenom into the third spot in the Mets’ batting order. Bambi advised Darryl “not to try to be Willie Mays. Just try to be Darryl Strawberry.”

By May 13, with an entire week of experience behind him, Darryl was surely neither Teddy Ballgame nor the Say Hey Kid. He wasn’t even Danny Heep. He’d played six games, totaled 24 at-bats and accumulated all of three base hits: two singles and a double. The Mets’ offensive savior was batting .125 (and the Mets were still buried in last place). Bamberger sat Darryl against challenging lefties like the Pirates’ John Candelaria and Larry McWilliams. Strawberry was lost enough against righthanded pitching.

Far from the expectations of New York, with Three Rivers’ smallest-ever crowd skipping Motown 25 and the Pirates throwing struggling veteran (and ex-Met farmhand) Jim Bibby, Bamberger started Strawberry in right. His first two at-bats produced a fly ball to center and a groundout to short. Darryl Strawberry, in almost total privacy, had lowered his batting average to .115.

But then, in the top of the fifth, a star was born.

Hubie Brooks was on second, reliever Lee Tunnell was on the mound and Darryl took the swing for which he and so many had waited. The result was also the desired one. The ball Strawberry hit traveled over the 375-foot mark on the left-center field wall to give the Mets a comfortable 7-1 lead.

Talk about a comfort zone. At last, in his 27th major league at-bat, Darryl Strawberry had arrived there, carrying with him his first major league home run, contributing to an 11-4 rout of the Buccos and shedding the proverbial monkey of initial pressure from his broad back.

“What you guys saw him do,” Bamberger told reporters, “he’s going to do a lot of.” Strawberry didn’t disagree: “I’ve been facing good pitching and it’s been tough on me. But I’m starting to get more aware of things. I wasn’t doing that before and if I keep it up, I know I’m going to have success.”

The manager and his right fielder were prophetic. Straw’s shot off Tunnell was the first of 26 he’d smack in 1983, establishing a Met freshman mark that has yet to be broken and earning him National League Rookie of the Year honors. He’d have a hundred home runs by 1986, the Met career home run record by 1988 and, before he left the team as a free agent following the 1990 season, 252 home runs as a Met. More than two decades later, no Met has come within 30 homers of Darryl Strawberry’s standard.

Maybe he doesn’t hold as many records as Michael Jackson was selling in May of 1983, but in the pantheon of Met sluggers, you can’t beat it.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 12, 1963, the Mets showed they could come out on top in a slugfest — and do whatever it took in the process. One Met in particular knew no limits when it came to effort. Casey Stengel had let it be known that if any Met found himself at bat with the bases loaded, fifty American dollars could be his if he “accidentally” allowed himself to be hit by a pitch. Fifty bucks was not insubstantial to the 1963 ballplayer, yet only one Met cashed in on the offer. With three on and one out, Hot Rod Kanehl stepped up and stepped into a delivery from the Reds’ John Tsitouris. That was using his head and his body, for Rod’s welt extended the Mets’ third-inning lead over Cincinnati at the Polo Grounds to 5-0. Kanehl HBP RBI was truly money because the Mets would eventually require every last run they could scrounge up in the second game of that Sunday doubleheader. Unaccustomed to pitching with a lead, Jay Hook gave it all away, and by the middle of the fifth, the Mets and Reds were tied at six. The Mets, however, came roaring back with five in their half of the fifth, capped by a three-run homer from Duke Snider. Suddenly it was 11-6 Mets. Then, just as suddenly, it wasn’t. Relievers Ken MacKenzie and Larry Bearnarth — “aided” by a Tim Harkness error — allowed the Reds right back into the game, then into the lead by allowing six sixth-inning runs. The Mets trailed 12-11 and stayed behind until the eighth when a pair of walks and a Harkness single set up Jim Hickman’s tying sacrifice fly and Choo Choo Coleman’s go-ahead single. The Mets led 13-12 heading to the ninth and, shockingly, won 13-12, as starter Tracy Stallard came in to stop the madness with a scoreless inning of relief, striking out rookie second baseman Pete Rose (who had been on base four times) to end the game. If this nightcap didn’t contain enough mythic elements already, consider that in their history, the Mets have given up exactly a dozen runs in 59 different games. This is the only one of those they’ve ever won.

GAME 032: May 13, 1970 — Mets 4 CUBS 0

(Mets All-Time Game 032 Record: 22-29; Mets 1970 Record: 16-16)

How close can you come? How close can a one-hitter get to being a no-hitter? Besides one hit, that is?

Gary Gentry found out for himself relatively early along the trail of tears better known as Mets Pitcher Near-Miss Gulch. You could pitch brilliantly, you could vanquish your opponent and, of course, you could earn a Happy Recap for your efforts, but you still missed the brassiest of rings.

In 1970, it hadn’t even been a decade that the Mets had gone without pitching a no-hitter. It didn’t yet stand out like a scorer’s thumb. Things were happening for the Mets. They’d won a World Series a mere seven months earlier, and nobody saw that coming. The no-hitter…it was bound to happen eventually.

As for Gentry, he was as good a possibility to throw it as any Met. He’d put up plenty of zeroes on plenty of scoreboards, judging by what he accomplished in just over a year in the big leagues. He won 13 games as a rookie in 1969, tossing the four-hitter that clinched the National League East title. Though he wasn’t around at its end, he started the game that gave the Mets their first N.L. pennant. And he won the first World Series game ever played at Shea Stadium — with lots of help from Nolan Ryan in relief and Tommie Agee in the field, but it was Gentry’s W.

First, Tom Seaver came up in 1967. Then, Jerry Koosman in 1968. Gentry was the next arm in that logical progression. In a way, it was no wonder Gary Gentry and Tom Seaver were able to fool out-of-town writers covering the 1969 World Series by trading uniform tops during a Memorial Stadium workout and dispensing disparaging quotes about “each other” for laughs. Nos. 41 and 39 were different pitchers, yet it seemed the Mets were cutting a string of hard-throwing righthanders from the same talented cloth. And now, in May of 1970, Gentry was attempting to one-up Seaver, who had thrown an intensely memorable one-hitter ten months earlier.

Like Tom the previous July, Gary was taking aim at a dangerous Chicago Cubs lineup, this time at Wrigley Field. It was the first meeting of the year between the two rivals whose fortunes passed in the midsummer night in ’69. Once again, the Cubs and Mets were one-two in the N.L. East, Chicago up by 2½ games in the early going. They had a hard-throwing righthander of their own, Bill Hands, going for them this Wednesday afternoon, and Hands would give his manager, Leo Durocher, nine innings and twelve strikeouts.

But Art Shamsky homered with no one on in the fourth and Gentry nicked Hands for his first hit of the year in the fifth, singling home Wayne Garrett. With a 2-0 lead, Gary became the story of the day, for he was pitching a perfect game at Wrigley Field.

Perfection lasted only until Ron Santo walked to lead off the home fifth, but Gentry erased that flaw from his ledger immediately, when he got right fielder Johnny Callison to ground into a double play. When Ernie Banks grounded to Garrett at third, the no-hitter was still intact. And when the Cubs could generate no more than two grounders and a strikeout in the sixth, Gentry was nine outs away from untrod Met territory.

Gentry received an enhanced cushion in the seventh when Garrett tripled home rookie Mike Jorgensen and Jerry Grote singled in Garrett to up the Met lead to 4-0. Perhaps Wayne’s presence in the middle of these Met rallies was an indicator that destiny was unfolding. The redhead wasn’t even in the starting lineup. He had come on to replace Joe Foy after Foy was hit by a Hands pitch (on, of course, the hand). Maybe that was the sort of sign Mets fans could take as gospel that Gary Gentry was really going to outdo what Tom Terrific accomplished on July 9, 1969 when he one-hit Chicago at Shea.

When he got through the bottom of the seventh by retiring Don Kessinger, Glenn Beckert and Billy Williams, Gary was only six outs away from making the Mets the fourth expansion team in the modern era to claim a no-hitter. Bill Stoneman of the Montreal Expos recorded one in 1969, his team’s first year. Bo Belinsky of the then-Los Angeles Angels chalked up a no-no in 1962, that franchise’s second season. And the Houston Colt .45s/Astros had been a veritable no-hit machine since entering the National League alongside the Mets in ’62, with Don Nottebart, Ken Johnson and Don Wilson twice turning the trick.

As the bottom of the eighth commenced, Gary Gentry and the Mets stood poised to join their ranks.

First up, perennial All-Star Santo. He flied to Agee in center for the first out.

Next, Callison, the former Phillie who won the 1964 All-Star Game at Shea with a three-run homer. He flied to Shamsky’s defensive replacement Ron Swoboda in right for the second out.

Four outs to go. The next batter would be Ernie Banks, another Cub with All-Star credentials (impeccable ones) and an 6-for-12 track record vs. Gentry in 1969. The two faced off in five games the year before and the pitcher never completely shut down the slugger in any of them.

Gentry worked Banks to a 2-2 count. On the fifth pitch of the at-bat, he threw a chest-high fastball that the pitcher wanted to come in with. “But,” as Gary would recount later, “I didn’t get it in enough.”

The goal was to get to Banks to hit the ball in the air. The wind was blowing in off Lake Michigan and Gentry figured he had a good chance to pop up Mr. Cub. But Mr. Cub had other ideas. He lined a looping fly ball to left. The left fielder, Dave Marshall, came running in and stuck out his glove in hopes of making a shoestring catch. The ball tipped off Marshall’s glove and fell in fair.

All eyes on official scorer Jim Enright…

Base hit all the way.

Marshall had no beef with the decision: “There’s no question but that it was a hit. I slid a little just when I got to the ball. At first I didn’t think I had a chance for it but the ball seemed to stay up and I went for it.”

Gentry couldn’t quibble either: “I’m glad it wasn’t a cheap hit.” But don’t think Gary wasn’t aware of what was going on. “I started thinking about a no-hitter in the fourth inning,” he admitted after finishing off what became a 4-0 one-hitter, “and kept thinking about it until Banks broke it up in the eighth.”

A 4-0 one-hitter over the Cubs…just like Seaver had done, though nobody was going to mistake Ernie Banks for 1969’s spoiler Jimmy Qualls. But as with Seaver’s gargantuan effort, a shutout victory was a shutout victory and a win that pulled the second-place Mets that much closer to the Cubs was what — in the standings, anyway — counted the most.

Gentry’s masterpiece went down as the fifth one-hitter in Mets history, filed alongside one apiece by Al Jackson, Jack Hamilton, Seaver and, earlier in 1970, Ryan. Five one-hitters in less than nine seasons, but no no-hitters…and with so many talented arms of late. Definitely a curiosity of sorts, though not a franchise trademark yet for a team still so relatively young. The Mets had achieved a miracle in their eighth year. Everything next to that world championship had to be considered a small wonder. Certainly they were capable of effecting small wonders after 1969.

Gentry would have to sate himself with the one-hitter and a whitewashing of one of the National League’s fiercest lineups. It was the fourth shutout of his career. Gary Gentry was 23 years old and the owner of a World Series ring. Who would have figured that at that moment in time, the middle of May 1970, he would have all the World Series rings and half the complete game shutouts he would ever collect?

Or that Mets pitchers collectively would still be one hit shy of their brass ring more than four decades later?

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 10, 1994, respectability enveloped the Mets one season after they performed as the most disreputable unit in baseball. With Bret Saberhagen having given up only two runs in eight innings but the Mets trailing 2-1 at Montreal, Dallas Green’s troops made one last stand against Expo closer John Wetteland. With two on and one out in the top of the ninth, center fielder John Cangelosi delivered his fourth hit of the day, scoring pinch-runner Ryan Thompson from third base to even matters at two. One inning later, with two out and nobody on, Joe Orsulak sent another Wetteland pitch over the right field fence at Olympic Stadium to give the Mets a 3-2 lead and Orsulak his fourth hit of the day. Reliever Doug Linton returned to the mound for his second inning of work and, when he struck out Montreal first baseman Cliff Floyd, the Mets had their fourth consecutive win and found themselves four games above .500 at 18-14, in second place in the newly realigned five-team N.L. East, 2½ in back of the recently transferred Atlanta Braves. If a modest winning streak engineered by the journeyman likes of Cangelosi, Orsulak and Linton doesn’t sound particularly momentous, understand that at the same juncture one year earlier, the 1993 Mets had already fallen irrevocably underneath an avalanche of failure and languished in seventh place in the seven-team Eastern Division, eight games under .500, twelve games out of first place with 130 to go. The manager was about to be fired, the general manager would soon follow and a 59-103 nightmare was unfolding in full. Therefore, just by playing competitively and conducting themselves professionally, the 1994 Mets were staking their claim as Comeback Team of the Year.

GAME 033: May 11, 2010 — METS 8 Nationals 6

(Mets All-Time Game 033 Record: 21-30; Mets 2010 Record: 18-15)

Teaching old dogs new tricks may present interspecies challenges, but new first basemen can apparently pick up on incredible acrobatic feats very fast. Ike Davis mastered his trademark trick before his major league career was one month old.

Ike was tearing up Triple-A pitching in the first half of April, just as he had done a number on Grapefruit League hurlers in March. Yet the Mets opted to send him to Buffalo for a bit more experience and to delay the start of his service-time clock, something worth considering in the long term if Davis delivered on his prospect promise. Were the Mets really that worried about losing him to free agentry in 2016? The man who drafted Ike in the first place, GM Omar Minaya, did not appear destined to be around by then — and had never really shown any interest in long-term ramifications of any player personnel moves — but he sanctioned the farming out of Davis and the reinstitution of former Met Mike Jacobs as the club’s starting first baseman to begin the year.

Twelve games into the 2010 season, the decision was clearly not working in anybody’s favor. Jacobs had little life left in his bat and the Mets were off to a 4-8 start. Davis, meanwhile, was hitting .364 and fast becoming a cause célèbre among results-starved Mets fans (WFAN’s Mike Francesa went so far as to hire a stringer from Buffalo to come on his afternoon show and report Ike’s daily progress). The Mets gave in to inevitability on April 19, ditching Jacobs and calling up Davis. Ike did not disappoint, going 2-for-4 versus the Cubs at Citi Field in his maiden game.

Mets fans figured they were getting a solid bat. What they might not have given much thought to was the rookie’s glove. It would in a matter of weeks, become Ike Davis’s calling card.

The first time Davis’s defense caught anybody’s eye was in his third game, an otherwise dreary 9-3 loss to Chicago at Citi. In the top of the first, with one out, Cubs second baseman Jeff Baker popped an Oliver Perez pitch foul to the right side. It appeared to be drifting out of play, but Davis tracked it, stayed with it and, even as it began to fall into the Mets dugout, didn’t give up on it. The rookie leaned in, grabbed it and held on, even as he tumbled head over heels.

“I landed on my feet,” Ike mused after the game, “so that’s good.”

The highlight reel had only begun. A couple of weeks later, the Mets were battling the Giants, again at Citi Field. The two teams were knotted at four in the top of the ninth (Davis had homered twice) when, with two out, Pablo Sandoval lifted a foul pop toward the Mets’ dugout. Once again, it was Ike taking nothing for granted…and taking away an at-bat from an opposing player. He lunged for the ball and held on as he replicated his head-over-heels tumble from the Cubs series. Again, he landed on his feet, with teammate Alex Cora standing by to steady him. The catch sent the Mets to the bottom of the ninth, where Ike would take off his glove, pick up his bat, work out a walk and score the winning run when catcher Rod Barajas launched the first walkoff home run in Citi Field’s brief existence.

Was this a thing now? Could and would Ike Davis make these sorts of plays at will? Once could be a fluke. Twice could also be a fluke. Think about the fan in the stands who catches two foul balls in a row. It doesn’t mean you give the fan a Gold Glove. Ike was just a young man on a hot highlight streak, maybe.

Maybe.

What is known is the Mets were lacking definites four nights after the Barajas walkoff. They were playing Washington in Flushing and were getting nowhere for the longest time, with Jon Niese struggling on a misty Tuesday night and the Mets trailing 6-2 by the middle of the eighth. With no warning or even a sense that warning would be required, the Mets turned their night around: a Jason Bay single, a David Wright double and a Davis ground ball that was thrown away by Nat shortstop Ian Desmond opened the figurative floodgates. Bay scored to make it 6-3 on the error. After the Nationals brought in the much-loathed ex-Yankee Tyler Clippard, Jeff Francoeur struck out swinging, but Barajas doubled in Wright and Davis to cut the National lead to a manageable 6-5.

Cora beat out a bunt to move the leaden Barajas to third. Rod then scored on Angel Pagan’s single to right. Now it was a tie game. Clippard remained in as Jerry Manuel deployed pinch-hitter Chris Carter, just brought up from Buffalo. In Carter’s first Met at-bat, the former Bison — nicknamed the Animal — lashed a double to right field. In loped Cora with the go-ahead run as Pagan sped to third. National manager Jim Riggleman changed pitchers, inserting Miguel Batista, and ordered an intentional pass to Jose Reyes to load the bases and set up a potential double play. But Batista couldn’t shake the wildness with which Riggleman afflicted him. Batista walked Bay, and the Mets were up 8-6.

The Mets had batted around and were still going. Wright struck out but Davis came up for a second time and bid to cap the inning with a dramatic grand slam down the right field line. Was it foul? Was it fair? The umpires initially ruled the former, but it was close enough (and Citi Field’s foul poles short enough) to trigger a video replay review. The Mets had done well in those situations in 2009 — about the only thing they had any luck at that year. Davis was certainly sure he’d hit one fair. For a rookie, even a rookie whose dad was a big leaguer, Ike had no hesitation when it came to expressing his views orally or by body language, and everyone could see Ike beseeching home plate ump John Hirschbeck that he though he’d hit a four-run four-bagger.

But it was not to be. The men in blue checked the video, concurred it was foul and Ike flied out to center to end the inning. Oh well, Mets fans were left to think — a grand slam would have been nice, but we’ve got a two-run lead and we’ll just have to take our chances with K-Rod.

Francisco Rodriguez was no sure thing coming out of the bullpen, despite a contract that paid him to as flawless as humanly possible. Nonetheless, he started the top of the ninth in uncharacteristically efficient fashion, popping up Josh Willingham to second on the second pitch he threw and grounding Pudge Rodriguez to short on his very next pitch.

But this was K-Rod. No sense counting chickens and appraising their hatching capabilities.

Ian Desmond was the Nationals’ final hope, the same Ian Desmond who had thrown away Davis’s grounder in the eighth and made it possible for the Mets to hatch their six-run comeback. He worked Rodriguez to 2-0 before lifting the next pitch foul. It looked like it would go into the seats behind the Mets dugout.

Or maybe…whoa, wait a minute. It can’t be.

But it is. It’s Ike Davis yet again. With the body language yet again. He’s drifting, just like the baseball. The baseball isn’t going into the seats. It’s instead descending through the airspace over the Mets’ dugout. And the Mets’ first baseman is determined to meet it.

The crowd braces spiritually as Ike prepares for impact. Once again, he’s grabbing the ball. Once again, he’s tumbling over the railing, right leg, then left leg. And this time, he has a veritable welcoming committee, as every Met who’s on the bench rushes over to fashion for him the softest of feet-first landings. The kid missed a grand slam by inches a few minutes before. No teammate wants him to make up for it by slamming helplessly into the cement below.

“It’s not that far of a drop,” Davis would say later, exhibiting the lack of fear that had marked the beginning of his Met journey. “I’d rather end the game than worry about getting a bruise.”

Davis holds onto the ball for the final out of a rousing 8-6 victory. The Mets, in turn, hold onto Davis. Fernando Tatis grasps him awkwardly between the legs, but it’s all in the name of safety, of preserving the long-term viability of the 23-year-old who has so quickly solidified his place in the Met future and crafted, via three breathtaking catches in a span of three weeks, a defensive legend.

That’s Ike Davis. You know…the guy who makes those catches.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 31, 1995, the Mets required rescue from their all-time saves leader. After overcoming a 3-1 deficit with three runs in the bottom of the eighth at Shea and putting Bobby Jones in position to gain a win for his solid eight-inning effort against the San Diego Padres, good old John Franco came in and did what most Mets fans swore he did all the time. Considering that by 1995, Franco had long passed Jesse Orosco for most saves by any Met reliever, it was a statistical fallacy to claim John Franco “always” blew leads. But perception feeds on certain realities, and on this Wednesday afternoon, there was no denying that Franco entered a game in the ninth inning with the Mets up 4-3 and promptly gave up the tying home run to leadoff batter Eddie Williams (the same Williams the Mets selected with their first pick in the 1983 amateur draft). Franco would eventually get out of the ninth and still be pitching in the tenth when he blew the 4-4 tie, though to be fair, this was more the kind of inning Franco usually experienced: an infield error allowing Bip Roberts to reach; Roberts racing to third on Tony Gwynn’s single to center; and Roberts scoring on Ken Caminiti’s grounder to second. Down 5-4, however, the Mets forgot about Franco and recovered. Jeff Kent and Joe Orsulak each singled and pinch-hitter Chris Jones belted a deep fly ball down the left field line for a three-run, game-winning pinch-hit home run. The Mets prevailed 7-5, with the W going to the pitcher of record when they came to bat in the tenth…good old John Franco.

by Jason Fry on 10 May 2011 1:14 am The game the Mets just lost is the kind of game I’ve come to associate with the post-humidor Coors Field: a quiet succumbing, like getting hugged by a python that squeezes a tiny bit more each time you exhale, so that little by little everything goes black. The game starts too late, ends too late, and features the Mets doing a whole lot of nothing before giving up a flukey hit or making a fatal mistake. At least when the Rockies played arena baseball you could huffily declare the whole thing a farce.

Chris Capuano was good, entertaining to watch not just for his masterful mixing of speeds and locations but also for his obvious annoyance at mistakes and misfortune. Capuano is a heart-on-the-sleeve pitcher who must drive umpires crazy, though those who have strike zones like Mike Winters’ rather elastic trapezoidal creation deserve a certain amount of provocation. Capuano, alas, was about all that was praiseworthy: The few Met hits were little chip shots, with the hardest-hit ball of the night — Jason Bay’s long fly to center that backed Dexter Fowler almost to the fence — clearly headed for the wrong part of the yard.

Even as we get nice stories about some 2011 Mets — the resurgence of Jose Reyes and Carlos Beltran, Daniel Murphy playing and learning at second, Ike Davis’s so-far superb sophomore season — we have to overlook some worrisome steps backwards. Josh Thole, for one, looks utterly lost at the plate: Keith Hernandez sounded like he was about to run down to the field and throttle him, channeling an urge felt by most every fan. With Jhoulys Chacin having lost the plate and desperately needing strike one with the bases loaded and two out in the fourth, Thole let a get-me-over fastball go right down the heart of the plate, eventually grounding out. Two innings later, with two on and two out, he compounded the error, ignoring a halfhearted slider on 3-1 and then working the walk, bringing up Capuano to strike out feebly. Thole looks like he can’t figure out which way is up right now, which is neither unexpected nor something he should be pilloried for, but is horribly painful to watch nonetheless.

And as 2011 goes on, I’m more and more worried about David Wright. I know he’s still a hugely valuable player, but remember when we were amazed at how a player so young could be saddled with an 0-2 count and feel like he had the pitcher right where he wanted him? Wright was constantly battling back to 3-2 and getting hits or at least pushing the pitcher’s tank closer to E, and it was wonderful to watch — a precocious young hitter who backed pitchers into a corner and forced them to meet him on his terms. Wright isn’t that player anymore — he racks up gobs and gobs of strikeouts, can’t seem to climb out of pitchers’ counts, and seems desperate at the plate a frightening amount of the time.

On the subject of smaller but still nettlesome problems, can someone send Willie Harris to the Boyer-Emaus Remedial Academy for Underachieving Youth already? Harris finally got a hit on a sheepish check swing past Troy Tulowitzki, then tried to steal second, in whose general vicinity he was spotted after Jonathan Herrera caught Chris Iannetta’s throw, read and annotated a chapter of Moby Dick, shaved and loosened back up with a round of vigorous calisthenics. I’d suggest hiring ninjas for the Harris operation, but honestly these days all it takes to eliminate him is a pitcher with modest ability.

Speaking of ninjas, the 2011 Mets are showing a knack for being done in by initially undetectable injuries. Jason Bay feels something pull on the second-to-the-last day of spring training and is marooned in St. Lucie for weeks. Angel Pagan feels something in his side, is pinch-hit for, winds up in Florida and now won’t be doing much of anything until God knows when. Worst of all, Chris Young — who’s looked very capable when actually pitching — can’t get loose in the bullpen and goes for a just-in-case MRI. Boom, anterior capsule tear, and there (in all likelihood) goes both Young’s season and his Mets career. No cringeworthy collisions, no teammates and trainers carrying grimacing guys off fields — just Mets exiting with some apparently minor ailment that proves major.

But then again, it’s a theme that fit tonight: Your 2011 New York Mets, Quietly Succumbing.

by Greg Prince on 9 May 2011 1:52 pm  Imagine if there had been no 1969. Perish the thought, but stay with me for a second. Imagine we’d gone from 1968 and its encouraging leap from 61 to 73 wins to the next season taking the Mets from 73 to 83 wins. Tom Seaver would lead the league in strikeouts and ERA while winning 18 games. Tommie Agee would set a team stolen bases record and hit 24 home runs. Donn Clendenon would drive in nearly a hundred runs. And, best of all, the Mets would participate in their very first pennant race, a three-way battle with the Pirates and Cubs, holding a piece of the top spot in the National League East as late as the 148th game of the season.

Looked at that way, 1970 would be a fantastic Met success. And, I’m guessing, if you told Mets fans at the end of 1968 to be patient, just wait, and in two years, you’ll have all that (after experiencing seven seasons when not losing 90 games was a stunning accomplishment), it would have been received gratefully.

But there was a 1969. It was real and it was spectacular. Thus, 1970, all of which occurred as described above, came off as little more than an Amazin’ letdown. We went from the Miracle Mets to merely mundane in the space of less than twelve months, proof that you can’t outdo a once-in-a-lifetime happening.

Mets highlight films, however, were never stopped from interpreting recent history in the best possible light. We’ll see how that propagandistic bent manifested itself when SNY debuts Mets Yearbook: 1970, 6:30 Wednesday evening, following the Mets-Rockies matinee.

As a personal aside, just as late summer 1969 was the ideal moment to discover the Mets, I have no problem with 1970 being my first full season as a fan. I must have liked what I saw, ’cause I’m still here.

Image courtesy of kcmets.com.

And check out the story of Jeff Gerst, from the last time we posted an advisory of a Mets Yearbook episode. It truly qualifies as Amazin’!

by Jason Fry on 9 May 2011 12:56 am One of my Little League career’s many lowlights was the day a searing liner was hit out to me amid the clover that covered right field — a place generally unexplored by balls and so not coincidentally where I and millions of other kids not destined for greatness have played. After some combination of misjudging the ball, chasing it and fumbling to pick it up, I got it in my grip and heaved it with all my might, nearly skulling the understandably startled center fielder.

I wasn’t completely useless, though. I had two talents which my coach learned to exploit, and that in hindsight seem like early signs pointing to a future as a blogger:

1. Though I had none of the physical skills required to play catcher, I knew quite a bit about the position from having my nose buried in baseball books all the time. So I was possibly the youngest catcher able to frame pitches and/or bring them back into the strike zone, at least to the satisfaction of the high-school umpires of late-1970s Long Island.

2. I could keep score, which freed up Coach to attend to such essential duties as breaking up rock fights and stopping half the team from making a beeline to the ice-cream truck mid-inning for Fun Dip and Pop Rocks.

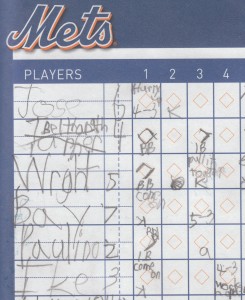

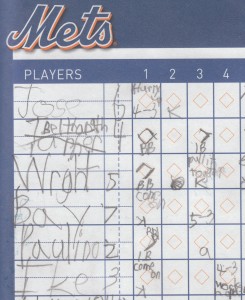

So far Joshua hasn’t had any on-the-field misadventures as cringeworthy as my 9-8 non-putout, thank goodness, and he can actually throw. But that aside, his Little League career is not all that different than mine. But now there’s a positive in that: Today he kept score avidly, save for the time needed to devour a Carvel cup of vanilla with rainbow sprinkles, recording every play from Jamey Carroll’s single to David Wright waving at strike three.

Part of the kid's handiwork He got the numerical equivalent of the positions at once, even shortstop, and was barely thrown by anything — the only play that caused him to furrow a brow was Matt Kemp’s fifth-inning GIDP, which was pretty challenging to account for up and down the scorecard. He even added editorial comments — Jason Bay’s first-inning strikeout includes a scrawled “come on,” Wright’s third-inning K is accompanied by “pull it together,” and Andre Ethier’s fatal home run is noted with “oh man.” Pretty much what I was thinking at the same time in each instance, minus the profanity and sputtered beer.

The Mets lost today. But all in all, that was a bump in the road:

1. It was my 42nd birthday, or my Jackie Robinson birthday as we decided to call it. I hope my Turk Wendell birthday sees a lot more pennants on the wall of World Bank Economic Liberalization Program Stadium, and doesn’t involve crabbing about the lack of a no-hitter.

2. My lovely wife graciously agreed to share Mother’s Day with me, and to mark it with seats for all three of us in the Pepsi Porch.

3. It was my first 2011 visit to Citi Field, the lack an issue of April deadlines and one brush with bad weather. We got a stupefyingly gorgeous day — hot in the sun, yes, but around the fourth inning the clouds came in and left everything pleasantly warm without the added touch of deep-frying.

4. Joshua proved impressively leather-lunged, bellowing at players and the Mets in general. Emily and I eventually tired of this, perhaps because we were hemorrhaging from the ear canals, but our Pepsi Porch neighbors were amused. Or at least tolerant.

5. Excused myself in the mid innings for a visit to the Promenade behind home plate with Mr. Prince. We drank foreign beers and discussed an upcoming project we’re excited about and hope you will be too.

6. Jose Reyes tripled. It was pretty great.

Not bad for a season debut. On the way out, with Joshua still a bit mopey about the loss, I tried to cheer him up by noting that “the second-best thing you can do with an afternoon is watch your baseball team lose a game.” He cocked his head a bit, curious, and I asked him what he thought the best thing would be.

He got that too. Time to teach him to frame pitches.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2011 2:43 am Remember Angel Pagan? Me neither.

Just kidding. Of course I remember Angel Pagan. Angel Pagan was the Mets’ center fielder before Jason Pridie. Pagan was pretty good at one point, I vaguely recall. Finished in the Top 10 in triples among National League batters two years in a row.

You know who else hit a lot of triples? Wally Pipp. Wally Pipp led the American League in triples in 1924 with 19. He was also sixth in games played with 153. There were several years when Pipp barely missed a game. Real fine player, that Wally Pipp. Real good right up to the middle of 1925. You look at his numbers and you see an all-around consistent player who just suddenly disappears from his team’s lineup.

Gee, I wonder what happened to him.

And speaking of Gee, I wonder how many of us on the eve the 2011 season saw the Mets rampaging to a third consecutive victory in early May using a herd of recent Buffalo Bisons. You know how we hang on every element of the Opening Day roster right up until the trucks are packed in Port St. Lucie? Well, we’re idiots. Whatever we obsessed on getting exactly right at the end of March is irrelevant barely five weeks later.

Dillon Gee. Mike O’Connor. Ryota Igarashi. Justin Turner. Ronny Paulino (him we assumed would be here sooner than later though we didn’t much care). Not one of them was an active Met when the Mets met the Marlins to start the season; all of them played a role in beating the Dodgers Saturday night. It started with Gee, who was pressed into service when Chris Young’s tight right shoulder reminded us he’s too good to be true, and it crested with Turner, the second baseman who wasn’t deemed sound enough to beat out All-Star nominee Brad Emaus yet was perfectly fine as a pinch-hitter in the eighth. Together, these recent minor leaguers who weren’t necessarily expected up here so soon teamed with several longer-tenured Mets to short-circuit Andre Ethier and other assorted men in blue.

Leading their charge once again was Jason Pridie, another erstwhile Bison, now a staple of Met lineups for years to come as far as I can tell. Pridie of the Mets, as moviegoers everywhere will someday know, showed up in New York with little fanfare and was soon the everyday center fielder for thousands of consecutive games, many of them stirring. Like the Friday night affair he won with a three-run home run. Like the Saturday night triumph he helped seal with three base hits.

On the day they ran the Kentucky Derby in Louisville, Jason Pridie proved a real iron horse, you might say. Got his batting average up to .300. Galloped home a couple of times. No stopping this fellow. Just pencil him in for the next decade or so.

Angel Pagan…I wonder what he’s up to these nights.

by Jason Fry on 7 May 2011 1:46 am Being of inferior genetic stock, I don’t have the faintest idea what it must be like to be a major-league baseball player, blessed with amazing hand-eye coordination and fast-twitch muscles and everything else I lack.

But I’m willing to edge not very far out on a limb to say this: It must be awesome being Jose Reyes.

There he was tonight, tripling twice and doubling and walking and stealing and coming home to score. He was everywhere, in perpetual motion, churning legs and flying hair and clapping hands. It must be a blast to be in there doing all that.

When Jose is really on — as he’s been for a happily long stretch now — he doesn’t so much hit balls as he attacks them, slashing at them with his bat and then lighting out after them on the basepaths. He’s around first before you’ve gotten beyond that initial instinctive YEAAAHHHHH!!!!! and you catch up with him making calculations as he nears second. With most balls in the gap, you assume a double and figure if everything breaks right the batter might wind up with a triple. With Jose it’s the opposite — you assume triple and hurriedly downgrade your expectations when you remember there’s a plodding runner stuck in front of him or a particularly rifle-armed outfielder behind him with bad intent. When he’s standing on second Jose tends to look pleased but also slightly disappointed, like a kid who got a nice piece of cake but saw the knife placed just on the wrong side of a perfect frosting rose. Jose on third is something different. It starts with the body hurtling to the ground, dreadlocks aloft, the toes stretched to drag in the dirt. We all know he shouldn’t be sliding head-first, that it’s as crazy for him to put his hands and wrists in harm’s way as it would be for a violinist to punch it up with some drunk at a bar. Yet, at the same time, it’s so cool, the way he locks on to the base as he goes by, using it like a fighter uses the arresting wire on a carrier’s deck. And then the look at the ump, daring him to deny what he’s just seen and all those people have just enjoyed. He gets the safe sign (unless Marvin Hudson is involved), but there’s still all this extra energy from his flywheel trip around the bases. So he has to clap, except when Jose claps he doesn’t clap like you or I clap — he whacks his hands together like a sugared-up kid with the biggest erasers in the world. Or he finds someone to point to. Or he just grins a million watts’ worth. Or maybe he tries out all three.

Two such Reyes trips to third would have been treat enough for most any night at Citi Field, but we also got Carlos Beltran as the undercard.

Beltran is an entirely different player to watch: expressionless where Reyes is exuberant, a quietly graceful machine where Reyes is a manic eruption of windmilling limbs. When Jose’s on he lunges at balls with an almost palpable hunger; when Beltran’s locked in he knows exactly what pitch he wants, identifies it and makes whatever minute adjustments are necessary to catch the ball with the fat part of his bat, employing his lethal swing as he has so many times before. Then he’s off, gliding to whatever his destination is and stopping there, mission accomplished.

None of this inspires Reyesian flights of fancy — if anything it plays into the hands of Beltran’s detractors, who register the absence of grimaces and fist pumps rather than the presence of well-machined execution. But I love to watch him nonetheless: I sometimes find myself surprised that a well-struck Beltran hit went as far as it did, because that sniper’s swing is so quietly perfect that it seems like it shouldn’t send a ball rocketing off into some distant corner of Citi Field, or sailing off to settle down above the Great Wall of Flushing. And seeing Beltran whole again — or as close as he can come these days — feels like a gift. The Mets haven’t been particularly lucky this year, but there has been this: Beltran is an everyday player where we wondered how much we’d have to hear he was resting, and we no longer worry about him when there’s a tricky bloop to right or an extra base that needs taking. He’ll get it and he’ll get there, and then he’ll be in there tomorrow.

There was more tonight, of course: one of Ike Davis’s patented blasts out of the yard; the delightful, unexpected sight of Jason Pridie lashing a game-changing three-run homer beyond the David Wright DMZ; and the oddity of having every Dodger intentional walk backfire soon after enduring every Giant intentional walk working to perfection. Not to mention that the 10-year-old who very capably delivered the first pitch — the son of a Red Hook firefighter killed on 9/11 — was named Chris Cannizzaro and yes he was named for the Mets catcher and yes he really is a fan. “Always hated the Yankees,” he explained coolly. Great all around, but watching Reyes and Beltran was best of all.

The Mets are having a confounding, which-way-is-up year, one in which there are encouraging stories but also too many holes to fill, at least for this campaign. I’ve been a fan long enough to know what’s coming. I understand that Beltran is in his final Mets campaign, and should bring back a decent prospect or two in the summertime, particularly if he’s still looking as sound then as he does now. I understand Reyes isn’t on base as often as he could be, that he’s lost time to injuries, and that he might be too expensive to bring back. But he remains a monster talent at a critical position, and he too might fetch a decent reward from some playoff contender on his way to free agency and a new home.

And perhaps that will be the right thing to do in both cases. Perhaps they will leave us and in two or three years we will love the players we got in return, young stars who have us giddy with the possibilities and whose names are front and center when we crow about the new core. That could happen, and we could be grateful it did. But oh, what a price. Carlos Beltran in Angels red would hurt, but Jose Reyes in San Francisco black and orange, only seen six times a year, might really break my heart.

I’ll savor every sweet swing and tumbling third-base-as-brake slide. We all should. But the more of them we see, the more we will have to wonder how many are left, and how we will feel when the answer is none.

by Greg Prince on 6 May 2011 4:36 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season consisting of the “best” 28th game in any Mets season, the “best” 29th game in any Mets season, the “best” 30th game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 028: May 1, 2011 — Mets 2 PHILLIES 1 (14)

Mets All-Time Game 028 Record: 23-28; Mets 2011 Record: 12-16)

Mets players had heard worse things shouted in their direction as they batted at Citizens Bank Park, but little in the Phillie fan verbal arsenal was as confusing as the chant that went up through the stands in the top of the ninth inning as they engaged the Phillies in a 1-1 tie. It wasn’t derogatory. It wasn’t about the game at all, but anyone tuned into ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball could be excused for making the connection.

The real world made an unannounced appearance at the park the locals call the Bank. Daniel Murphy was pinch-hitting for Justin Turner against reliever Ryan Madson when the chants went up:

U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!

Murphy clearly didn’t know what was going on. Shots of both dugouts indicated similar cluelessness among the Mets and the Phillies. But across Citizens Bank Park, right around 11 o’clock, the word had gotten out: The USA — its military, at any rate — had killed Osama Bin Laden. ESPN viewers learned about it a couple of minutes earlier when play-by-play voice Dan Shulman broke the news of an impending White House announcement to sports-minded America. Fans in the stadium, armed as they tend to be with portable mobile devices, picked up on the story right around the same time. They broadcast to each other what was going on.

U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!

No Mets fan couldn’t be taken back ten years, to September 11, 2001, to when the name Osama Bin Laden became regrettably familiar. Wrapped in the reluctant flashbacks, however, was a baseball-shaped beacon of hope. Ten days after the terrorist attack on New York, baseball resumed in the city, at Shea Stadium. It was the Mets who took the first step toward bringing New Yorkers back to something resembling normality. It was Mike Piazza who made many forget the horrors of two Tuesdays earlier when on Friday night, September 21, he hit a breath-taking home run against Atlanta. The Mets won that game that just about everybody instantly decided was more than a game.

Now, a decade later, coincidence or something had the Mets on a baseball field when the engineer of those evil attacks had been at last eliminated. They weren’t in New York, they weren’t aware of what was about to be announced in Washington, they had no idea what had taken place that day in Pakistan. But there they were anyway, them and the Phillies and the wired fans who were letting it be known that this was suddenly also, maybe, more than a game.

U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!

“I don’t like to give Philadelphia fans too much credit,” David Wright would say eventually, “but they got this one right.”

Murphy went down swinging for the second out of the top of the ninth. Wright walked and stole second but was left there when Jason Bay flied out to center. David was the thirteenth Mets runner left on base through nine innings. Their limited offense, combined with Chris Young’s strong seven, was enough to build a 1-0 lead, but the bullpen gave that back in the bottom of the eighth when Ryan Howard went the other way on Tim Byrdak for the tying RBI. Frankie Rodriguez allowed a couple of Phillies to reach in the bottom of the ninth — the Mets’ closer’s modus operandi early that season tended to involve baserunners — but Philadelphia didn’t score.

Extra innings commenced as President Barack Obama stepped to an East Room podium and confirmed what had been reported. Bin Laden was indeed dead. It took a painstakingly planned, rigorously executed operation, but the ten-year mission to take out this global public enemy was at last successful. Crowds were now gathering outside the White House to celebrate. Same thing was happening at Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan where the World Trade Center had stood until 9/11/01.

The Mets and Phillies played on. And on. They were the only game in baseball as Sunday night became Monday morning but hardly the only thing on anybody’s minds. One who had his thoughts divided was ESPN analyst Bobby Valentine. Valentine was the manager of the Mets in 2001. As those Mets threw themselves into lending their celebrity and their facility to recovery efforts (Shea’s parking lot served as a staging ground for rescue workers and Met players and coaches joined in loading supplies onto trucks when not quietly visiting firehouses and hospitals), nobody gave himself over to New York more forcefully than Valentine. Between directing logistics and comforting families of victims, he hardly slept during the middle of that September — and he still managed to lead the Mets to three consecutive wins in Pittsburgh before the game when Piazza homered and so many cheered so cathartically.

In the ESPN booth, Bobby V kept his emotions in check as best he could. He explained afterwards, “When I heard it was confirmed I got choked up.” The former manager conceded it was “an emotional couple of seconds there” before he “threw a little water on my face” and resumed analyzing.

As for the 2011 Mets, they went about business as usual. They kept leaving runners on base, sixteen through thirteen innings, not making the most of three shutout frames from rookie reliever Pedro Beato. But in the fourteenth, there was a breakthrough. Ronny Paulino, making his first start behind the plate for the Mets, notched his fifth hit of the long evening, a double to left that scored Wright to give the Mets a 2-1 lead. The Mets then left the bases loaded (nineteen through fourteen), but in the end, the LOBs proved as irrelevant as #OBL — Bin Laden in Twitterspeak — proved gone. Taylor Buchholz retired the Phils in order in the bottom of the inning to secure a 2-1 win for the Mets in fourteen.

Inside the victorious clubhouse, there was naturally enough talk about Paulino’s feat — and how the backstop, in a way, echoed Piazza’s accomplishment against Atlanta from 2001 — but mostly the questions for the Mets regarded what they were thinking when they heard the chants and what this all meant to them considering that their predecessors were such an enduring sidebar to the New York aftermath of 9/11. Young, a Princeton student that September, watched Obama’s speech in the clubhouse after his seven two-hit innings were done: “There are some things bigger than the game and our jobs.” Beato was a newly minted high school freshman in Brooklyn who went up to the roof and witnessed the smoke rising from the World Trade Center: “I couldn’t stay up there that long. We didn’t want to get in trouble.”

Manager Terry Collins admitted he had no idea why the fans were chanting in patriotic unison when they started but that bench coach Ken Oberkfell clued him in to what was going on far from Philadelphia, far from baseball. But baseball is never far from the minds of those paid to play it and guide it. Third base coach Chip Hale put the whole thing in perspective for Collins when the last out was recorded, telling the skipper, “That’s as big a night as we’ll have in a long time. We got Bin Laden and we won.”

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 4, 2007, age was paired with beauty when Julio Franco broke his own record as the oldest man to homer in major league history. Starting at first base as the Mets took on the Diamondbacks in Phoenix, Franco, 48, made his feat that much more one for the ages by launching his second-inning four-bagger — into the Chase Field pool — off fellow fortysomething (43) Randy Johnson, no easy mark for any demographic. Although both men had been playing big league ball since the 1980s, it was the first time Julio had ever gone deep versus the Big Unit. Most of Franco’s perceived value as a Met was as a clubhouse sage, but in this 5-3 win at Arizona, he proved he could still get around the bases…and not just via the trot. Franco set himself a second record before turning in that Friday night when he became the oldest man in major league history to homer in the same game that he stole a base: second, in the ninth. Julio didn’t last much longer as a Met, but nobody ever got more mileage out of his own maturity.

GAME 029: May 5, 2006 — METS 8 Braves 7 (14)

Mets All-Time Game 029 Record: 31-20; Mets 2006 Record: 20-9)

Maybe the cliché that attaches itself to managers making every last move in an unyielding battle of wills versus their opposite numbers should be, “They played that game like it was the 29th game of the regular season.” It would have been true the Friday night that Willie Randolph, Bobby Cox and their respective units wore each other down across fourteen messy innings in 2006.

The Mets hoped they’d eventually land somewhere in the vicinity of the actual cliché, the one that invokes seventh games of World Series. They were off to a hot enough start in 2006 (in first place from the third game of the season on) and they were stubborn about not cooling off. The Mets had already immersed themselves in a monthlong stretch in which they would play sixteen home games and win eight of them in their final at-bat. Of those eight “walkoff wins,” this Shea showdown may have been the most thrilling, grueling and absurd of them all.

Consider that it was against the Braves, still perceived as the Mets’ great threat after nearly a decade of chasing them, though for a change it was the Mets looking down at third-place Atlanta in the standings. As the Mets attempted to add a little more distance between them and their southern foes, they undertook a mini-marathon that would have fit comfortably alongside the Grand Slam Single game.

At various points, the Braves held one-run leads of 1-0, 2-1 and 3-2, but it was a 6-2 deficit that stared the Mets in the face as they batted in the bottom of the seventh. Steve Trachsel had lasted six characteristically (for 2006) mediocre innings, leaving the Mets in a 4-2 hole. The usually reliable submarine specialist Chad Bradford didn’t help matters by giving up two in the top of the seventh. The offense sputtered, too, as the Mets left seven runners on base between the second and the fifth. Braves starter Kyle Davies had held the Mets mostly at bay, save for a Carlos Beltran homer in the first and a bout of wildness in the third that included three walks, a wild pitch and a bases-loaded fourth ball to David Wright.

Davies seemed in command when the seventh began, but he didn’t come close to seeing its end. Jose Reyes led off with a single to center and Paul Lo Duca ground-rule doubled, keeping the speedy Reyes from scoring. Davies left in favor of Macay McBride, who induced a grounder to third from Beltran, but it was not handled by Shea favorite Larry “Chipper” Jones and Reyes came home on the error. A Carlos Delgado ground ball found a hole to score Lo Duca, and suddenly it was 6-4 after batters.

Out went McBride, in came Ken Ray to go after Wright. Ray was partially successful, limiting David to a fly ball to right, but it moved Beltran to third. Cliff Floyd singled to right, getting Beltran home from there. After a passed ball and an intentional walk to Xavier Nady (the first of four Cox was to order), Kaz Matsui singled in Delgado from third.

Now it was tied 6-6. Airtight Met relief was provided for the next three innings by Aaron Heilman (seven up, six down) and Billy Wagner (a spotless tenth). The Mets generated leadoff baserunners in the eighth — a Reyes triple — and ninth — a Nady walk — but couldn’t cash them in as Ken Ray gave way to Oscar Villarreal, Oscar Villarreal gave way to Mike Remlinger, Mike Remlinger gave way to Chuck James and Chuck James gave way to Peter Moylan. Moylan, the seventh Coxman to pitch that night, put down the Mets 1-2-3 in the tenth.

There was finally movement on the scoreboard in the eleventh when Wilson Betemit led off the visitors’ half with a home run off Wagner. Billy, in his first season as Met closer, was proving a double-edged sword, usually stabilizing ninth innings for Randolph but being susceptible to some badly timed bombs — one to Washington’s Ryan Zimmerman at Shea in the first week of April, another, more frightening shot to Barry Bonds toward the end of the month in San Francisco. The Bonds bomb forged a ninth-inning tie and the Mets came back to win at AT&T Park, so Billy could be forgiven that faux pas (and besides, it was Barry Bonds). But would Wilson Betemit sink the Mets on Cinco de Mayo?

To borrow the native tongue of so many Los Mets, “¡No!”

Oh, Wagner would make it fairly interesting, by allowing a single to the next batter, Marcus Giles, who would steal second with one out and take third on a Chipper groundout. Randolph instructed Wagner to intentionally walk Andruw Jones (one of two IBBs by Met pitchers) and Billy threw sand in the eyes of the Braves rally when he induced a lineout to center from Braves rightfielder Jeff Francoeur.

Still, with Sandman exited, the Braves had just crafted their fourth one-run lead of the increasingly late night. Chris Reitsma came on to close out the Mets in the bottom of the eleventh, but he must have picked up something from Wagner, for he, too, came down with a bad case of first-batter gopheritis. Cliff Floyd, who entered the game with an unsightly .185 batting average, ripped Reitsma’s second pitch of the inning deep to right and the Mets had knotted their fourth tie of the night at 7-7.

Reitsma righted himself and sent the game to the twelfth. Duaner Sanchez, who hadn’t been touched for a run yet in his first 14 appearances covering 19 innings, kept up the phenomenal work. The Mets tried to make a winning pitcher of Sanchez when, with two out in the bottom of the twelfth, Beltran doubled. Cox made with another intentional walk, to Delgado, but then saw the strategy go shaky when Reitsma walked Wright unintentionally. Back to the plate came Floyd, with a chance to duplicate what he did to start the eleventh. This time, though, Reitsma prevailed, striking out Cliff and making this at least a thirteen-inning game.

No problem for Sanchez. He set down the Braves 1-2-3. Cox had issues in the pen by now, for he’d used everybody at his disposal, so he went to a starter, Jorge Sosa, to serve as Atlanta’s ninth pitcher of the night. After a leadoff walk to Nady — one of nine not sanctioned by the Braves manager — Sosa stiffened and escaped trouble. Randolph had to go to a seventh hurler himself (sixteenth overall between the two teams), Jorge Julio. The reliever who came over from Baltimore with minor leaguer John Maine during the offseason in exchange for Kris Benson got himself in trouble to open the fourteenth when he gave up a single to Chipper/Larry. Jones would get as far as second, on a stolen base, but Julio popped up Francoeur and grounded out Adam LaRoche to leave him there. The Braves had gone 4-for-18 with runners in scoring position.

In the bottom of the fourteenth, as the clock neared midnight, it would be the Braves’ catcher who would open the door to Atlanta disaster. Sosa didn’t help by walking Beltran with one out, but he popped up Delgado to Chipper for the second out. Now facing David Wright, he threw a pitch that got by Brian McCann for a passed ball (his second). This was key because with Beltran on second instead of first, Carlos was able to score the winning run when David Wright’s ground-rule double — his third hit and sixth time on base — bounced over the left field fence.

The Mets took their first lead of the night, 8-7, at one minute before midnight. No better time to get in front than on the last swing of the evening.

It wasn’t close to easy to get there. The Mets ran through five pinch-hitters, each of them going 0-for-1. They left nineteen baserunners on and went a dismal 4-for-21 with runners in scoring position, grounding into three double plays along the way. Leadoff man Jose Reyes alone reached base six times in eight opportunities but was brought home only twice. The leadoff triple that didn’t become the go-ahead run in the eighth (the bases were left loaded when Floyd grounded to first) was particularly gnawing.

In the end, however, these 2006 Mets were, per the British, quite chuffed with their Churchillian determination. Wright: “We are not going to roll over.” Beltran: “We are never going to give in.” Randolph, in the role of prime minister, added, “We kept scrapping and clawing. It was a big character win for us.” It was left to Cox to concede: “We had it won twice. We gave it up twice.”

So the Mets didn’t have to pay for their sins…at least not immediately. They won the game but they’d be back at work in almost no time, with a matinee scheduled a little more than thirteen hours hence. All Willie Randolph could hope for at that point was a long and effective outing from Saturday’s starter.

He’d find out soon enough what he was in for.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On May 9, 1982, Rusty Staub did something he never did the first time he was a Met. Le Grand Orange came to Queens from Montreal at the start of the 1972 season and, before he was unceremoniously traded to Detroit by M. Donald Grant, slugged 62 home runs in four years. It was the sixth-most in franchise history at the time of his departure, but not one of those 62 ended a game. Then again, all 62 were hit when Staub was in the game as a right fielder. As a regular in Yogi Berra’s and Roy McMillan’s lineups, he was going to come up when he was going to come up. But when Rusty returned to New York prior to 1981, he was on the verge of adapting to a new role: pinch-hitter deluxe. Staub began ’81 as the club’s starting first baseman, but with the emergence of Mookie Wilson in center, the trade for Ellis Valentine to play right and the realization that Dave Kingman’s defense was best hidden at first, Staub, 37, gravitated to the bench where became the Mets’ main man in a pinch. By 1982, he was ensconced in that job, and few could do it better. Rusty’s brilliance as the guy you’d count on to come through in a tight spot never shone brighter than it did when George Bamberger sent him to pinch-hit for Craig Swan with two out in the bottom of the ninth of a 5-5 game versus the Giants. Rusty came through in that tight spot, all right, belting his first Met walkoff homer. The game-ending shot versus Greg Minton gave the Mets a 6-5 win and went down as the one of two walkoff home runs (both pinch) of Staub’s two Met tenures.

GAME 030: May 6, 2006 — METS 6 Braves 5

Mets All-Time Game 030 Record: 26-25; Mets 2006 Record: 21-9)

Length. In the modern baseball parlance, it’s a manager’s fondest dream when he is starting a pitcher who isn’t particularly consistent. On a Saturday afternoon at Shea Stadium, Willie Randolph had a real bad hankering for length out of the righty to whom he was handing the ball against Atlanta, Victor Zambrano.

Leaving aside Zambrano’s credentials for a moment — and all Mets fans really cared about where Victor was concerned was that he wasn’t Scott Kazmir, the top pitching prospect the Mets mysteriously gave up to get him two years earlier — the biggest factor facing Randolph’s club at 1:10 PM was that they were barely out of Shea before coming right back to the ballpark.

It was as if the Mets had played Friday night for all the marbles only to discover a fresh set of marbles had been placed before them about, oh, ten minutes later. The game the night before was an 8-7, 14-inniing thriller of a win, but the nearly five-hour festival of attrition, which ended at 11:59 PM, took plenty out of the Mets’ bullpen, particularly its big three of Aaron Heilman, Duaner Sanchez and Billy Wagner. They’d each pitched two innings, and it would behoove Willie to not have to use any of them at all.

Thus, when Zambrano was given the marble, so to speak, it was imperative that he handle it for as long as he could.

That plan went out the window almost immediately.

Zambrano didn’t blow up in the first inning or anything like that. To the contrary, he looked fantastic, retiring Marcus Giles, Edgar Renteria and Chipper Jones in order, striking out the first and third of them (Jones on a 3-2 count). The Mets got him a run in the bottom of the first and Victor appeared poised to protect the 1-0 margin. His seventh pitch to leadoff batter Andruw Jones in the second — his 23rd overall — was as beautiful a pitch as he ever threw as a Met. It was a breaking ball that made Andruw appear amateur. He swung, he missed, he was out…and so, somehow, was Victor Zambrano.

Seemingly without waiting for strike three to be officially registered, Zambrano took off for the Met dugout, his left hand grabbing his right arm. Something was terribly wrong in two senses of the word. Obviously the righthander experienced something painful. It turned out to be a torn flexor tendon in his elbow. Victor Zambrano, a quiet soul who received a lot of flak from a lot of fans for not being Kazmir (the kid who was blossoming into a star for Tampa Bay), would never throw another pitch as a Met. He’d only garner 23 more innings with Toronto and Baltimore the next year before fading from the majors altogether.

That would become the long-term story for Victor Zambrano, and it’s rather sad, but its only immediate consequence for the Mets on May 6, 2006, was his departure left Willie Randolph shorthanded for pitching in the second inning after using seven arms the night before.

What to do?

First thing Randolph did was signal the bullpen for Darren Oliver, the one regular reliever he didn’t use on Friday night. Oliver was generally Randolph’s long man, and his assignment Saturday afternoon was to go as long as he possibly could. Darren warmed up, retired his first batter, Adam LaRoche, on three pitches…and gave up a home run on his fourth pitch to his second batter, Jeff Francoeur.