The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 30 June 2008 7:16 pm 2: Saturday, September 27 vs. Marlins

As the Countdown Like It Oughta Be reaches its penultimate milepost, there is not a soul in Shea Stadium who isn't prepared for its unveiling in the middle of the fifth inning. Much to Aramark's dismay it is momentarily killing hot dog and beer sales, but tradition is tradition by now. All wait to find out who is next to unveil a magic number in this stirring seasonlong salute to the history of the old ballpark that is scheduled to commence to vanish after tomorrow. The buzz is palpable considering how closely the Countdown has been monitored. All of New York is wondering how this thing will play out. That's why when the public address system plays over and over again a familiar tune with a revised admonition — “EVERYBODY CLOSE YOUR EYES!” — nobody questions the directive; every pair of eyes shuts and every pair of ears perks up. What they hear, crackling over the PA, is a voice. It is ancient, yet, given a moment to be fully comprehended, it is instantly recognizable. Eyes stay closed and the voice begins to speak…

I have been requested by management to give Shea Stadium a benediction, or at least the new parking lot that will provide amazing, amazing, amazing space to all the fine automobiles that the customers will drive to the Mets games even though there is an understandable effort by municipal authorities to encourage you to take mass transit as it is considered splendid at this time to be green, which is exactly what I was when I first came to New York in Nineteen Hundred and Twelve, which was technically Brooklyn though it was more technically Greater New York considering the great consolidation that took place while the National League had twelve teams including one in Louisville but none in Kansas City which is where I come from and everything was up to date and they went and built a skyscraper seven stories high which I thought was high which just goes to show you what kind of road apple I was when I came to Brooklyn and played in the new ballpark in Nineteen Hundred and Thirteen, my second year which wasn't no sophomore jinx for me as I averaged two-seventy-two and they called the neighborhood Pigtown and you wouldn'ta wanted to play there except that was where the money was in those days and the ballpark Mr. Ebbets built was quite fine and now I see they're replicating it in what used to be the parking lot for this here fine stadium that they're tearing down to make new parking and that's progress for ya.

I am not here to argue about other sports, I am in the baseball business and in the baseball business if you don't have advancement you don't have progress and progress is what makes arbitration possible, which is something you didn't have in my day which I might add was many a day ago but I continue to be employed as a vice president by the New York Mets regardless of the fact that I am dead at the present time but I signed a perpetual personal services contract with Mrs. Payson who is also dead at the present time and extends her best regards. Mrs. Payson signed a long-term contract with the consolidated city of Greater New York for Shea Stadium which was quite a sight in its day which I suppose is not a day that has many days left and long-term don't mean what it used to when you open a bright and sprightly new stadium and it's got fifty-four bathrooms so nobody, even the ladies, has to wait and miss a minute of the action which you don't want to do, not at the prices of admission which can go as high as platinum what without Ladies Day as a recognized promotion and gold, which was the kind of watch I didn't even get when I was discharged by the New York Yankees for making the mistake of getting old and losing a World Series when Mr. Mazeroski took my pitcher Ralph Terry over the wall and Mr. Berra couldn't do nothing but just stand there and watch and it was a great moment for the baseball business if not for me and, wouldn't ya know it, Mr. Berra followed me to the amazin', amazin', amazin' Mets and Ralph Terry followed him if not for very long but I had commenced to no longer managing due to my hip breaking in a most unfortunate manner. When I slipped and got hurt in Boston when I managed there, the newspapermen wasn't at all unhappy but my newspapermen when I managed the Mets was always kinder to me.

The New York Mets did me a great favor when they was still the Knickerbockers and needed a manager to help them become the amazing Mets and I was involved in banking in Glendale which isn't for everybody and now I see the Mets have gotten into the banking industry with their new park which will have a name like a bank and a platinum ticket structure though you never can tell until you install the turnstiles and determine what the market will bear. I was fortunate that nobody much expected anything out of my Mets and we delivered even less but they came out to the Polo Grounds which was where I played for Mr. McGraw and learned my managing trade, not that you'd think it did me any good based on our record in the Mets' first year, which wasn't as splendid as you'd like but nobody seemed to mind because they did come out in record numbers to see my amazing, amazing, amazing Mets up there at the old ballpark which was a lot newer when I was, too. Of course I wasn't born old, which you might think the contrary of when you get a look at me now and you could say the same for Shea Stadium with the acres of parking for all the Ramblers which I only mention because they had an official car of the Mets deal the park's first year and later Plymouth paid for that honor and they're still reaping dividends because that was the year we won our first title and the newsreels still show that now and again and it became a very famous title as it ensured that in South America on New Year's Day we'd have our best game. I also heartily endorse annuities as a wise investment.

I ain't no Ned in the third reader, not after a hundred and eighteen years of living and dead combined, so I've seen a few things but I had never seen anything quite like Shea Stadium and not just the bathrooms which is where I wouldn't blame our fans for hiding in when the ballgames began to get away from us which was often and early and sometimes both, but it was a step up from the Polo Grounds which had been around almost as long as I was, maybe almost exactly the same amount if you count it in years before the fire and I mean the fire in Nineteen Hundred and Eleven, not when I got fired for losing a World Series and my old friend George Weiss hired me to manage those Knickerbockers who wasn't yet the Mets and George's wife said she married him for better or worse but not for lunch, which my Edna might have been thinking after George and I each made the mistake of getting old but that won't happen to this bee-yoo-ti-ful Shea Stadium because it's only forty-five years old and it won't see forty-six except of course in the way you're hearin' me now, which in itself is amazing, amazing, amazing.

You see and hear a lot where I am. You see George and you see that lawyer fella Mr. Shea and you hear a real nice broadcast from my men Lindsey and Bob and you have that other Lindsay, the mayor who likes to pour the champagne over your head which is fine if you just won as we did in Nineteen Hundred and Sixty-Nine and you got a big power-hitter at first base like Mr. Clendenon which I didn't or a hammer like Mr. Milner when we won a pennant again in Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Three which I didn't neither. I had Mr. Throneberry who failed to touch most of the bases and we was always afraid of what he'd drop next and he comes up to me these days and says he doesn't know why they asked him to be here but I hand him a piece of cake and he don't ask me anything else. Up here you know what you're doing. You can play Kanehl anywhere and he don't even have to stick his elbow out for fifty dollars and you always get the right Miller, the righthanded one, up to face the righties though on our team it didn't really matter which Miller or which Nelson we called on because we just wasn't that good. But we got the attendance and I apologize to them all if they feel they got trimmed by our performance. They probably did.

The escalators didn't always work at bee-yoo-ti-ful Shea Stadium but they made for grand staircases when they didn't and our scoreboard didn't always work the way they said it would, especially in the runs column, but it was big and everybody always knew how much we was losing by but ya didn't need a scoreboard 'cause ya had those placards and I'd just look at 'em and see what our fans thought of us which was a lot better than I thought of us. We got the old fans who came to the Polo Grounds and to Ebbets Field and we got the kids who didn't know any better. We got 'em from four years on, we got 'em from ten years on, fifteen years on, eighteen years on. And we got 'em in a group! When you're young, it's great to go into a stadium where your future lies in front of you.

Seems Shea Stadium, which was lovely, just lovely, a lot lovelier than my team, just commenced to being and now it won't be anymore. But you can be sure as I was when Mr. McGraw put the bunt on that it will always be here, sort of the way I am. Of course I once missed that Mr. McGraw pulled the bunt sign in Cincinnati and I got fined for it which is how it should be if you miss a sign and swing away. If ya wanna be a sailor, join the Navy. From where we put our new ballpark in Nineteen Hundred and Sixty-Four you could see the water, too. You could get here by boat, you could get here on the train which is how I traveled most of my career. You could fly into that big, noisy airport that disturbed so many of our opposing hitters that it was a boon for my pitchers except they didn't seem to care for it either and even if they had, my pitchers wasn't quite what you'd call pitchers all the time, at least not in the big league sense. And you could drive, even if it wasn't a Rambler, the official car of the Mets. You could park anywhere. We had lots of parking. It appears apparent that we still will.

I don't mean to be no Alibi Ike and I'd like to be with you fine ladies and gentlemen to pull down my number, but that's gonna represent a stretch as I am, as previously mentioned, dead at the present time, having commenced to being exactly deceased in Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Five which is no excuse for not being a New York Met, 'cause that's what I am for life and thereafter, just like you, I suspect, just like bee-yoo-ti-ful new Shea Stadium will always be, when you keep your eyes closed, bee-yoo-ti-ful new Shea Stadium.

The transmission crackles to an end. When all realize the voice has been silenced — or perhaps just paused until another appropriate interval when it will speak and speak and speak again — all open their eyes and turn their heads toward the right field corner where they discover the voice's physical envoy, Mr. Met, will do the honors on behalf of the spirit of the voice and peel off number 2.

That Mr. Met is resolutely mute strikes some in the crowd as ironic but nobody says anything about it.

***

Number 3 was revealed here.

The Shea Stadium Final Season Countdown will conclude with the unveiling of Number 1 in two weeks, on Monday, July 14.

by Greg Prince on 30 June 2008 2:22 am When a modern contrivance becomes a grand tradition, mister, you're growin' old. So it is with the Subway Series, quite obviously a cynical money-making scheme — hatched in the aftermath of a bad-for-business labor dispute, designed as a no-brainer crowd-pleaser, schemed to lure in those who couldn't be bothered with a regulation N.L. or A.L. game. After a dozen years of this stuff, the whole concept still sticks a figurative tongue out at baseball's timeless sense of ritual.

But time isn't timeless, y'know? Time has passed since Interleague play introduced itself to us, a pretty darn long time. It's been eleven years since Dave Mlicki laid down the first marker and a decade since the whole shebang came to Shea. It comes back every spring or summer and that, by definition, makes it tradition.

A special tradition, it turns out. The Mets-Yankees series every year stops the clock for me. Even as I am the first to observe and acknowledge it doesn't rock the packed house the way it did at the very beginning when a moment's silence was to be avoided because your sworn enemy might otherwise have the last word (and that was before the lineups were introduced), it's not yet humdrum and I doubt it ever will be. A special tradition deserves to be treated specially.

It deserved my friend Rob, he who gritted and groaned with me through seven innings of the first Subway Series debacle at Shea Stadium on June 26, 1998 and, for good measure, a bonus pounding at Yankee Stadium on June 10, 2000. Rob has waited not just ten years but his whole life, really (including Saturday), to watch the Mets beat the Yankees in person. How could I think of going to the final Subway Series game at Shea Stadium and not think of Rob?

It deserved my friend Richie, he who materialized without warning on the morning of July 10, 1999 with three tickets to that Saturday's Mets-Yankees game, one for him, one for his son, one for me. The day ended with each of us raspy — something about a 9-8 win captured on a pinch-hit, two-RBI single with two outs in the ninth affected our throats adversely yet did our hearts a world of good. I couldn't speak clearly for weeks after. When I next saw Richie at Shea, in August, he said he couldn't either. How could I think of going to the final Subway Series game at Shea Stadium and not think of Richie and his son?

His son, strangely enough, has aged nine years since Matt Franco's day in the sun and had a “gig” today, I learned; he's a drummer now, which is strange, 'cause in my mind he's eleven and eleven-year-olds don't have gigs even if twenty-year-olds apparently do. Thus, that left me with an extra ticket from the four my friend Sharon graciously passed in my direction when she determined her family couldn't make it from deep in the heart of Jersey all the way up to Shea.

Who deserved this fourth ticket? I had put out a couple of feelers to fine folks who, for whatever reason, were unavailable, until I discovered there was one person I never dreamed would want a piece of this action.

Stephanie! After listening to me come home hoarse and cursing over what wonderful or terrible incident had transpired in the boiling cauldron of hatred that Shea became every May or June or July when the Subway Series returned, my low-key wife finally grew curious enough to dip a toe in and discover for herself what all the fuss was about. That, plus she hadn't seen Rob or Richie in quite a while and she'd figured out from television that the ol' Subway Series tension, it ain't what it used to be.

And it ain't. How could it be? How do you match the stunning sense of juxtaposition from 1998 when Yankees and Yankees fans louted among us? How do you keep up the chanting that defined 1999's get-togethers, the constant din of Let's Go Mets! challenged by Let's Go Yankees! trumped in turn by Yankees Suck! made too often moot by the deleterious actions of one the grayshirts on the field? Some said it would never be the same in any June after they did this in October of 2000. I don't think that's it. It's novelty, or the lack thereof. Today marked the 33rd time the Mets played the Yankees at Shea Stadium in the regular season, the 66th time the Mets played the Yankees in the regular season anywhere in New York since 1997. The Mets and Yankees have played each other in recent seasons just about as much as the Mets have played the Rockies. Even allowing for hostility born of proximity, the 66th time isn't likely to be the charm.

And it wasn't. Oh, I don't mean the game itself, which was reasonably tight, or the result, which was absolutely agreeable. I don't give a damn if it's the 666th time they meet (at which time Satan himself will still be playing short for them), the Mets beating the Yankees is capital stuff. It will always mean more than the Mets beating the Rockies and, if we take our full dose of truth serum, more than the Mets beating the Braves, Phillies, Cardinals and Cubs combined.

But we don't chant nearly as much anymore. We chant more than we do against the Braves, Phillies and less inflammatory National League opponents, but there's far less anxiety about leaving a rhetorical vacuum unfilled. The catcalls wear themselves out. There's actually full at-bats that don't elicit any particular passion. Stephanie and I got up to stand in the Carvel line in the sixth and I didn't worry all that much that I was missing the Subway Series.

Then came the top of the ninth. Then came the Subway Series that I know and love and loathe. Then came Billy Wagner out of the pen and it was the second game in '06, the one where Sandman poured enough salt on a 4-0 lead to turn it into an extra-inning loss, all over again. Then came Jeter up to bat and it was…well, it could have been any of dozens of death knells. Sure enough, Ford boy singles just past Luis Castillo and, sure enough, bill.i.am bounced a wild pitch and Captain Intolerable was on second with nobody out and Alex Rodriguez still up.

Now it was that Saturday in May of 2006, the Billy meltdown special, the one I hadn't been to but felt every bit as scarred through the TV and radio as I was for the ones I had absorbed up close. Now it was the Sunday the May before, Jose and David not handling their positions particularly well. Now it was a Friday night in June of '02, Armando Benitez burning off the last of his save-percentage goodwill and Satoru Komiyama welcoming Robin Ventura home with arms wide open, and the Friday night the year before when Todd Zeile, on second, coached Mike Piazza, on third, to get thrown out, at home (while Yankees fans directly behind predicted every misstep with uncanny accuracy). Now it was the first one in '98, O'Neill doing in Rojas, Rob and I sporting mood rings that were stuck on black.

Every Sunday at Shea, they play Bobby Darin's “Sunday in New York,” the ditty about the “big city takin' a nap”. Until the top of the ninth, we were all pretty much asleep by Subway Series standards. Not anymore. I was awake and I was incensed. All day the presence of Skankophiles was no worse than offensive. Now it was worse. Now they were in the way of happiness and vindication. It was these people and their cause who had made Rob miserable since 1998. It was these people who yesterday tripped up Dave Murray, who'd been waiting for a win in these parts since 1991. It was these people who front-ran and ruined junior high for me, who were insufferable to work alongside in my late thirties, who piss me off by their very existence.

I hated these people. If Yankees fans were an actual ethnic group or religion, I'd be on the Justice Department's watch list for likely intent to commit hate crimes. If I talked about a race or a creed the way I talk about Yankees fans, I'd not be accepted in polite society.

Guy in front of me was telling a Mets fan in the top of the ninth, “rings…26 to 2…that's why we're going to win,” and I swear it was all I could do to keep my voice modulated as I snarled “choke on it, choke on it, CHOKE ON IT!” If he'd heard me, I'm not convinced I would have seen how the game ended because I'd be dragged away by walkie-talkie-wielding men in orange golf shirts.

But he didn't hear me and I remembered that the things I say to the television set probably don't belong in public, so I focused on Wagner and Rodriguez and the tall fly ball A-Rod lofted to the warning track. I focused on Endy and knew it wasn't going out. I knew Jeter could nail himself to second for at least another batter, even if it was Posada and even if Posada shouldn't have been guaranteed a stick in the inning but was thanks to the dopey fielding of Reyes and/or Delgado earlier.

This was indeed the Subway Series I knew and loved and loathed. The clock stopped. The world waited. Nothing mattered more than the Mets beating the Yankees.

Billy Wagner got Posada to ground to Reyes who didn't throw it away. Then he struck out Wilson Betemit, he whose seventh-inning shot screwed up air traffic at LaGuardia if not Ollie Perez altogether.

Then it was last year's Saturday game, a cold and wet May afternoon when David Wright unofficially opened Citi Field. It was the chilly Sunday night the May before when Wright and Delgado cleaned up Wagner's lingering mess. It was Piazza buzzing Clemens on a Friday night very late in the last century and it was, of course, Matt Franco when Richie and I and a couple I never saw before or saw again crafted a group hug that would put Dr. Phil to shame.

Not that dramatic this time, but I couldn't resist pounding laconic Rob on the shoulders before high-fiving him to certify that schnieds were abandoned and monkeys could find new perches on others' backs — Rob had seen the Mets beat the Yankees. I couldn't wait to slap palms with Richie and couldn't help but get in the way of him and Stephanie reaching to do the same. I couldn't wait to give Stephanie live and in-person emoting to the bliss of Mets 3 Yankees 1 as opposed to the way I breathlessly and scratchily recounted Mets 9 Yankees 8 several hours after it was over nine suddenly long years ago.

That's tradition, I think. That's a feeling of being part of something significant and ongoing, even if in fact there will never be another regular-season Subway Series game at Shea Stadium, even if I've probably seen the last of Rob and Richie at Shea Stadium. It's not a sure thing, but I generally don't get to more than one game a year with either of them these days and how exactly do you top the last Subway Series game at Shea Stadium, the last Mets win over the Yankees at Shea Stadium? Whatever else they've been to me, Rob and Richie have been two of the Mets fans I've been closest to as Mets fans, and we did that at Shea Stadium. When I asked if they'd mind posing with me for a picture just before we left, I didn't say why. I didn't have to.

by Greg Prince on 29 June 2008 2:00 pm In honor (if we can call it that) of the New York Yankees visiting Shea Stadium for almost certainly the last time ever, here are some superfun facts relating to their history as our guests from long before anybody was annoying enough to institute Interleague play.

• Shea Stadium was considered awesome and thrilling when Yankee Stadium was considered lame and passé. For any self-respecting Mets fan, this would describe any moment at any time right up to and including the present. In 1967, it was a fact of the competitive marketplace, relates Philip Bashe in Dog Days, an engaging account of the Yankee dynasty's fall from grace. Yankee Stadium was painted and freshened up as a reaction to Shea Stadium's modern allure four decades ago, “but 3.7 million square feet of brightly painted walls and seats alone wasn't enough to enliven stagnant Yankee Stadium, which in the absence of a winning club had none of Shea Stadium's Mardi Gras ambience,” Bashe wrote in his 1994 book. “Outfielder Ron Swoboda played for both New York teams during losing eras. Now a TV sportscaster in New Orleans, he compares the atmosphere in each venue in the light of his new home: 'Yankee Stadium was like a funeral; Shea Stadium was like a jazz funeral.'”

• The Bugs Bunny curve was for real. For one day it was. On September 29, 1969, the Mayor's Trophy Game between the National League Eastern Division Champion Mets and the fifth-place Yankees was played at Shea Stadium using what Red Foley of the Daily News referred to as a “new experimental baseball” that promised “10% more hop than the normal ball now in use”. The umpires had sixty of the rabbit balls at their disposal, all designed to enliven offense at the end of the year that came a year after the Year of the Pitcher. Once the five-dozen spheres had come and gone, regular N.L. balls were put in play. As Foley put it, home plate umpire Paul Pryor switched from those “autographed by 'Bugs Bunny'” to the regulation kind “signed by Warren Giles,” the senior circuit president. By then, the Mets were en route to a 7-6 exhibition win in front of 32,720 fans…and on their way to the world championship.

• Maybe there was enough room for another New York team besides the Mets. One of the seminal moments in my life as a fan was an article that ran in the June 1972 edition of Baseball Digest. It was titled “The Battle for New York,” and it traced the history of our city's game from the supremacy of the Giants in the early 20th century to all that went wrong when Babe Ruth came to town to the salvation wrought by Casey Stengel in the 1960s. This piece, which I recently reacquired through eBay, is what

a) made me an after-the-fact New York Giants fan

b) made me despise the New York Yankees more than I already did for ruining John McGraw's good thing

c) allowed me to connect the Giants to the Mets by what author Richard Watson wrote regarding 1964 at Shea Stadium: “Where once McGraw had watched chagrined as the public had veered away to the Yanks, Casey now watched joyfully as the turnstiles clicked and the Mets topped the Yankee attendance records. The man they had shoved aside had returned to shove them out of their number one spot in New York baseball and it was now the Yankees' turn to find out that popularity does not rest on victory alone.” Then, of course, came '69 when triumph married lovability and the Mets “were at the very top of the entire baseball heap. Meanwhile, the Yankees continued to struggle for victories just as they had been doing a full half-century previously” when McGraw's Giants were the toast of old New York.

The kicker, from the vantage point of '72, was that recent Yankee strides toward competitiveness signaled that it was beginning “to look as if New York was again the possessor of two competing ball teams who were both reaching for stardom” and that “there is still enough interest in New York to support two vigorously competing teams.” Yes, you read that right: the Mets were a given as New York's team. The Yankees, whom Watson noted were still negotiating for the renovation of Yankee Stadium and threatening to move to Jersey if they didn't get it? If they tried real hard, they could stick around.

I can't stress enough for purposes of historical context that this was the local Zeitgeist amid which I grew up as a baseball fan, leading me to sincerely view any alterations in the early '70s dynamic between the mighty Mets and their scuffling cousins to the north as merely temporary and clearly aberrational. The Mets are nobody's little brother. They are, in the worldview that was confirmed for me at the age of nine, a singular sensation of an only child.

• Baseball even sounded better here. When the Mets graciously shared Shea Stadium with those who were renovating in 1974, Toby Wright played the organ at Yankee home games. Fans, said the Yankee scorecard, could look forward to “enjoying the improved sound system offered by Shea Stadium”. Improved versus 1973 at Shea or improved versus what the Yankees left behind? I'm going with the latter. Nothing but the best for Jane Jarvis.

• Scoreboard like it oughta be. In Marty Appel's classy memoir Now Pitching for the Yankees, the team's longtime PR man recalled that the Shea Stadium scoreboard was National League all the way: “[It] couldn't handle the letters DH in the lineups, so we settled on an awkward B (for 'batter').” The interlopers might have seen that as a flaw. Those of us who've called Shea home would say it was intelligent design.

• Our house — in the middle of 126th Street. For every Mets fan who gnashes teeth at the sight of a vertical swastika in the stands at Shea, just remember: we started it. Well, kinda. Philip Bashe on the Yankees' sublet years: “Because of Shea Stadium's accessibility, bored Mets fans got into the habit of infiltrating the stands when their darlings were out of town. Bobby Murcer, Thurman Munson and other Yankees favorites suddenly heard boos at 'home.'” Many these days complain it's bush that Mets fans chant “Yankees Suck!” when the Mets aren't playing the Yankees, as if the Yankees somehow stop sucking when they're not around. But there was a moment in time when Mets fans showed up at Shea to tell the Yankees how much they sucked and the Mets weren't playing?

Excuse me, I think I've got something in my eye.

by Jason Fry on 29 June 2008 3:02 am Every so often the Mets win in spite of themselves. The Yankees — and damn them for making me say this — do everything possible to maximize their chances of winning.

Last night Pedro walked six Yankees. Four of them scored. Today Santana walked four Yankees. Three of them scored. Last night Sidney Ponson — he of the island-sized girth and island knighthood — walked four Mets. Today Andy Pettitte walked three Mets. How many of those Met free passes turned into runs?

None.

Seven out of 10 walks converted into runs for the Yankees. Zero of seven for the Mets. Kind of all you need to know right there.

There's some bad luck involved, of course — last night, with the bases loaded and one out in the third, Ramon Castro hit a 3-1 pitch from Ponson hard but right to Jeter. Nothing to criticize there. But overall? The Yankees have been through Giambi's near-death experience and Posada's injury and they look profoundly sound: They work counts, they execute, they have a plan. Sometimes a plan that's undone by lousy relief pitching (Farnsworth did his best to ruin Pettitte's outing today), but it's a plan. The Mets? They get picked off second with their best hitter locked and loaded at the plate trying to tie up the game.

I give up on trying to outguess this profoundly perplexing team — for at least the 10th time in this profoundly perplexing year. This afternoon I got briefly excited to read that Ryan Church should be back tomorrow and Moises Alou could return for next weekend. As if there's any guarantee that Church will remain sound after his body makes contact with a wall, or that Alou will remain sound after his body makes contact with a mild summer breeze. As if there's any guarantee things will change with both of them out there, should that actually occur. After all the evidence to the contrary, what on earth makes me think things will change? I mean, will I briefly get excited when I read that El Duque is long-tossing? I shouldn't, but I undoubtedly will.

We're like rats in a particularly cruel and possibly pointless experiment. We live in a box. There's an orange and blue button in it. About half the time we push the button and a treat pops out of the wall for us to scarf up. About half the time we push the button and get the bejeezus shocked out of us. Periodically the guys in the white coats futz around with the wiring and move the box around, but you know what? I think they've lost track of what they're trying to prove. Because at least from my perspective here in the box, the results don't change. We eat and yelp, we yelp and eat, and since all we've got is a single button to push, we sit in here and try to divine a pattern where there may well be none.

by Greg Prince on 28 June 2008 12:09 pm Sip it, savor it, cup it, photostat it, underline it in red, press it in a book, put it in an album, hang it on the wall, Dan Rather might have reported — the Mets won all three games they played against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium in 2008. Yet somehow it came to pass that on the very day our beloved New York Mets crushed the despised New York Yankees in Yankee Stadium and swept, in however delayed a fashion, their entire season’s slate of games in The House That Uncouth Built, I concluded the night more anguished than ebullient.

Timing is everything.

No denying the beauty and wonder of the afternoon game nor the enormous accomplishment inherent, considering the ten previous attempts since the inauguration of Interleague play, in Metaphorically blowing up Monument Park not once, not twice but thrice in the same year, the third time with an offensive explosion as astounding as they come. It took eleven tries to go three-and-oh on the wrong side of the Triborough, but it happened; it happened at the end of a week that began as Mariner mulch and it happened at the beginning of a day no Mets fan with any sense of history could have anticipated with anything but pathos. The two-ballpark precedent was too strong to ignore, too daunting to embrace and too horrible to contemplate. But the first half of the obstacle course was nothing more than a child’s jungle gym, Carlos Delgado rising up as the righteous kid who put a stop to all the bullying at that playground your mother warned you against wandering into.

Delightful. Absolutely delightful it was to sit on a Long Island Rail Road train en route to a Mets game listening to a Mets game, one whose pinball score was soaring to TILT. Delgado hit another homer? Delgado set an RBI record? Delgado, for the moment, was no longer playing like Delgado? Let me emit satisfied noises from under my earbuds. Let me smile and clap without outward elaboration. Let me make sure to catch several Yankees fans’ eyes with my expressions of satisfaction. Let me make sure to start spreading the news, I’m leaving the train.

“Hey,” I helpfully related with a hearty pat on the shoulder to a total stranger at Woodside, “fifteen-five!”

“Yeah, I know. But thanks!”

The 7 from Woodside was just as nice. An express came immediately and it wasn’t overly crowded. I could stand by a door for maximum AM reception, hear Howie Rose and Wayne Hagin charitably devote half-an-inning to their wistful memories of the doomed Yankee Stadium (funny, neither of them mentioned Mlicki). The proceedings uptown dawdled on just long enough so I could get a “put it in the books!” at the precise second I descended the final step from the back staircase that leads one onto Roosevelt Avenue and off toward sacred ground. I listened to the Mets win a game as I prepared to watch the Mets win a game.

My preparation for the nightcap was sound as it was sudden. Tickets I had no notion of holding magically appeared hours earlier, FedExed into the palms of my hands by someone looking out for my best interests. Jim and I joined forces just after six and secured Subway Series pins before they could sell out. We then beelined to the table where you trade in unwanted old caps on shiny orange Mets models. These are our annual priorities and we took care of them immediately (fretting over hats and pins…we’re like ladies shopping, I said). Through the good corporate graces of a great old friend who joined us a bit later, we had nine-inning access to the usually restricted Field Level. When you’re not down there often, it’s a culinary and souvenir wonderland. Jim had to restrain himself from purchasing a $65 bat. My gastric judgment notwithstanding, I bought from the Broadway Brew House a hot dog the approximate size and price of a Louisville Slugger, a wiener I’m still digesting as of this morning.

What the hell? Everything seemed to be going down so beautifully Friday evening. The Mets mysteriously didn’t play a loop of afternoon highlights or even post a Game One score where anybody could revel in it, but like the fellow with whom I shared bonhomie on the platform at Woodside, everybody knew what had been achieved in the Bronx. From far right field, a ripple of applause went up when the Mets’ bus pulled in to the lot behind the bullpen. The travel team is back! And they’ve got the trophy! The ripple extended around the sparsely populated ballpark as our kids, our Mets, tromped into the clubhouse to change for the nightcap. Boy, did we love our Mets.

What was not to love?

What a day it had been. What a night it would be, Pedro versus Ponson, Monumental momentum arriving in Queens with a police escort, an in-progress sunrise/sunset shutdown operation so effective it would do Derek Bell proud. It was all set up so beautifully…

Too beautifully. Pedro had nothing. Ponson had Reyes swinging at the first pitch and popping it up with the bases loaded and one out in the second, a sign as sure as any bogus vacation-ump interference call that all Subway Series day-night doubleheaders eventually run off the tracks. Sure enough, those who should have been wallowing in deserved misery were granted obnoxious salvation for Friday. We who should have been basking in the cool of the evening were suffering from a case of the cold nine-nothing sweats. As the hour neared eleven o’clock, even Jim’s vaunted impression of Walter Matthau couldn’t turn us back into the Sunshine Boys we’d been before 8:10.

You won 15-6 this afternoon? That was this afternoon. This is tonight. What have you done for us lately?

On June 27 — all of it — it should have been enough that Carlos Delgado drove in nine runs and the Mets smashed the Yankees at Yankee Stadium the way they stomped them there on May 17, savaged them there on May 18 and swept them there for 2008. It should have been enough that we won all three games we played at Yankee Stadium this year. By the end of June 27, however, it wasn’t. There was hardly enough time to sip it, savor it, cup it, photostat it, underline it in red, press it in a book, put it in an album and hang it on the wall before the split felt as if it had been spun into a loss.

I demand a recount.

by Jason Fry on 27 June 2008 11:04 pm Maybe the Mets get blown out tonight. Maybe pitchers dropping throws and middle infielders letting balls go through them aren't so easily dismissed around 11:30 tonight. Maybe we've used up all Bannister-like escape artistry available to starting pitchers. It's baseball, after all.

But for now, let's just enjoy this baseball siesta. Let's bask in the afterglow of a game that went from tense and interesting (Dan Giese throwing darts, Mike Pelfrey watching bloops and dinks and parachutes dent his ERA) to not at all tense and very enjoyable. Pelfrey got progressively less impressive after the first inning (he sawed apart Jeter despite a non-call from Tim McClellan, the Human Rain Delay of umpires), but he wiggled out of trouble. Our wretched-on-paper lineup (Nixon-Anderson-Tatis-Schneider is a lot of dead wood) proved more than equal to their softer-than-usual lineup. (Wilson Betemit? Justin Christian?)

And there was Carlos Delgado. At this point, no one familiar with Delgado or the 2008 Mets would put money on this being the start of the turnaround for either of those entities. (Heck, Babe Ruth hit three dingers in his twilight as a Boston Brave in May 1935, and it meant they lost 115 instead of 116.) But man, wasn't that fun? The double off Edgar Ramirez in the fifth was the smallest blow but the most-heartening development: With a 2-0 count and the game tied, Delgado stepped out to gather himself and all of us watching (from the stands or in front of the set) leaned forward, aware that this was a Big Moment and hoping that Carlos would find a way to convert. The grand slam was the big exhale, the blow that rendered the game safe. And the three-run homer was pure happiness — no sooner had Gary Cohen got out that Delgado had a shot at the club RBI record than Carlos made it so. Baseball's at its best when the tension ratchets up excruciatingly with each pitch and foul and flashing of catcher's signs, but sometimes it's also a lot of fun when everything happens very quickly.

OK. Whew. Exhale. We don't know what the future holds — we never do — but the day's been fun so far and it's a nice summer night. Let's play two!

by Greg Prince on 27 June 2008 4:42 pm

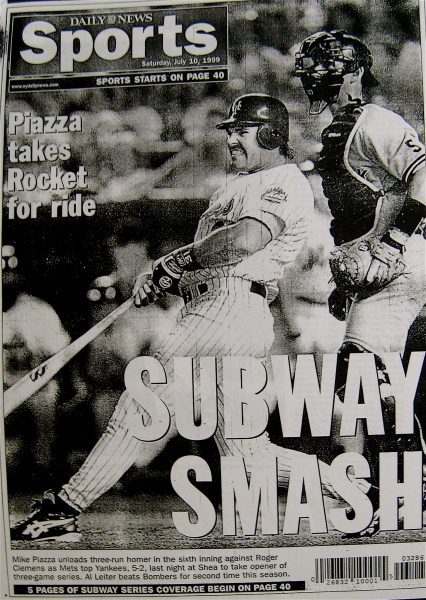

Before he was upstaged the next afternoon by the obviously more legendary Matt Franco, this Mike Piazza fella had himselfa pretty fair Subway Series moment on July 9, 1999.

by Greg Prince on 27 June 2008 3:38 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Tales From The Log, a final-season tribute to Shea Stadium as viewed primarily through the prism of what I have seen there for myself, namely 372 regular-season and 13 postseason games to date. The Log records the numbers. The Tales tell the stories.

7/9/99 F New York (A) 1-1 Leiter 10 81-76 W 5-2

The Matt Franco Game you know about. The Matt Franco Game requires zero explanation or elaboration. The Matt Franco Game defines itself. It’s the Matt Franco Game.

On another day, a Friday or any day (because there’s no bad day for it), the Matt Franco Game will get the attention it richly deserves in this space. But how about a little love for the night before the Matt Franco Game?

It richly deserves that. It is quite possibly the most forgotten wonderful game in Shea Stadium history, its satisfaction and drama practically obliterated as it was by the Matt Franco Game less than 24 hours later. But it happened. And it’s worth remembering.

If I can remember. I remember the Matt Franco Game so well. I remember the heat it generated that July afternoon, though it wasn’t so much the heat but the stupidity of roughly one-third of the house that Saturday afternoon. But the same heat was in abundance the Friday night before, the same invasive stupidity, too. It was the same combatants: Mets versus Yankees, Mets fans versus whoever else was in the stadium. If it wasn’t quite as sizzling as it would be Saturday, it was pretty hot Friday.

Didn’t know I’d be there ’til Friday morning. I came to work in civilian clothing. I was wearing a Liberty shirt. Laurie got word from her friend Dee who was married to Rick who worked for the Mets that he could leave us tickets if we wanted ’em. Of course we wanted ’em. And of course I would redress for the occasion. At lunch, I ran to the nearest Sports Authority and bought a black Mets t-shirt. I loved the Liberty in those days but not enough to wear their shield into battle at Shea.

When Rick left tickets (which was surprisingly often in those days), it was usually at Will Call. On this night, Dee waited for us by the Mets offices. She’d be sitting where most of the families of those who had important jobs with the Mets sat. That section, behind home plate, demanded a certain level of decorum. The tickets for Laurie and me were one flight up in Loge. Dee said she wished she could sit up there and act like a real fan. The three of us indulged in a quick and relatively quiet round of Yank-ees SUCK! before heading to our respective seats. Wives of guys who worked for the Mets in positions like those held by Dee’s husband Rick couldn’t or wouldn’t be caught dead enjoying themselves too much.

Laurie and I didn’t have such constraints, even if a few others in our section, Loge 15, might have. This, I learned from previous encounters with Dee & Rick generosity, is where the passes left by Mets employees for non-family wound up. Fine seats, free seats, no complaints. The demand was so great for a Mets-Yankees game that some family got bumped up here. Laurie recognized a couple of women named Niela and Militza. They were married to Met employees named Benny and Luis. The pecking order sent them from Field Level to Loge. They didn’t look at all unhappy to be here.

I was thrilled. I faced this Subway Series with only a television as far as I knew until that morning. My only experience with face-to-face intracity hatred had been the year before, the first time it came to Shea. That was dreadful as it was novel. I felt no compulsion to jump back in for 1999, to buy a six- or seven-pack, to make certain I would be there for the first year they’d do a home-and-home with the crosstown rivals. But given the opportunity, of course I said yes, of course I bought a shirt, of course I’d settle for sitting among the spouses of scrubs. As long as they didn’t mind sitting among the likes of me, I could be big about it.

When I last left the Subway Series, before the conclusion of that original NYY @ NYM affair, people were yelling back and forth with no break. It was as if a year and change hadn’t passed between June 26, 1998 and July 9, 1999. We were still yelling. Nothing was passé about this yet. Everybody still required the last word…no, the last syllable, whether that syllable was METS! or EES! or SUCK! We wore our hearts on our sleeves and made sure our sleeves were blue, orange and black.

Who should the Yankees send out to attempt to put us in what was thought of as our place at our place? Why, Roger Clemens, his first appearance at Shea as one of Them. It certainly wasn’t his first trip to Shea Stadium, however. Who could forget the blister that led him to beg out of Game Six in ’86 (he claims McNamara pulled him against his wishes, but would you really believe anything Roger Clemens has to say?). His next start was eleven years later, an Interleague oddity wherein the Toronto Blue Jays — Roger loved being a Blue Jay when they gave him the money to do so — alighted in Queens in early September. Juan Acevedo beat him and Rey Ordoñez stole his thunder by homering (albeit off Kelvim Escobar), but the fun of that night in 1997 was abusing RAAAAH-jurrrr before he departed after six having given up 7 runs and 10 hits.

He didn’t suck nearly that much in his next Shea start in ’99, but the Mets still had his number. He’d been less than a True Yankee despite a good record in his latest mercenary incarnation (anybody else remember wretching at the sight of those MSG Network ads that touted “Roger’s Ring Size”?). He didn’t lose until the Mets stopped him cold in June at Yankee Stadium. He might have been en route to the Hall of Fame, but we didn’t fear Roger Clemens. We loathed him, but we didn’t fear him.

On our side, there was Al Leiter, who was actually having a pretty horrific year, with an ERA tickling 5 through the first half. I don’t know if the Yankees feared Al, but they loathed facing him. He was a Subway Series staple; O’Neill once grumbled something to the effect of “it’s always Leiter, Leiter, Leiter” (quite a surprise that Paul O’Neill would grumble). Al indeed had it going on against his original team. It was Mets 2 Yankees 2 through six, another nailbiter, hopefully not another heartbreaker like the Friday night the year before when the gods ruled against us in the case of Rojas v. O’Neill.

The best news in 1999 was Mel Rojas was, like O’Neill’s homer the year before, long gone. Steve Phillips couldn’t bear to simply eat and swallow his contract so he traded him to L.A. for their headache Bobby Bonilla. Bobby Bo II promptly became our head and stomachache. God, he was huge. Also a huge a-hole, sniping at Bobby Valentine for not playing him and his .159 average more often. Just before hitting the DL in early July, he got into it with a fan. When Bobby Bo gets back on the deferred payment gravy train in 2011 (why can’t we just bite a bullet like a normal franchise?), he’ll no doubt be assigned to customer relations. Anyway, no Rojas in sight. Leiter stayed in and stared the Yankees down. Clemens did his part, too, pitching competently through five.

Ah, but then the sixth:

Fonzie singled.

Oly walked.

Mike Piazza stepped up.

I mean he stepped up. He stepped up and stepped on Roger Clemens’ throat, just as he did in the Bronx in June, just as he would one June later after which Clemens figured out the only way to keep Piazza at bay was to knock him out of action. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The whole point of recalling July 9, 1999 today is that it gets overlooked in the wake of what followed on July 10. On July 9, Piazza, himself having a lousy time of it with runners on for several weeks, nearly burst out of his home pinstripes and ripped a Rocket pitch to left. It took off. This wasn’t a moonshot like he launched off Ramiro Mendoza the next afternoon. This was a laser beam. This was 5-2 Mets.

“In terms of importance, velocity and quickness leaving the park,” Bobby V said later, Piazza’s pow “rates right up there with the best of them. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t think it would get high enough to get out. It was very, very impressive.”

As, I must add, were we, the Mets fans among the 53,920. RAAAAH-jurrrr returned. YANK-EES SUCK blew through the crowd. And, because we are at heart a positive tribe, LET’S GO METS carried the night.

In his followthrough, Mike’s bat dangled like a drill off a workman’s tool belt. He had put in a good day on the job. He had drilled a homer. He had drilled a hole in Clemens’ psyche. Had drilled it into our heads that this was our house and ours alone, that this was our town as much as anybody else’s. Dave Mlicki may have drawn up the plans for the Subway Series in 1997, but Mike Piazza drilled into its rumpus room every last bit of excitement we could imagine.

Unlike a year earlier, Al stayed healthy and stayed in through eight. Bobby V then handed the ball to new closer Armando Benitez, promoted by happenstance when John Franco’s thumb sidelined him. We loved Armando then. He was the eighth-inning guy everyone just knew would get the ninth inning sooner or later. Let it be sooner. This guy could blaze. Why’d the Orioles ever give him up?

Brosius doubled. After two outs, Chad Curtis walked. Then a wild pitch advanced them to second and third.

Oh, that’s why.

Typical Armando up to that moment was Benitez blowing away the opposition, so AB putting runners on seemed aberrant. But the Yankees making our lives difficult didn’t. All that separated him and us from disaster was Chili Davis pinch-hitting.

Chili Davis owned Doc Gooden when Doc Gooden was Doctor K for real. Chili Davis making our lives difficult seemed all too familiar.

Armando punched him out anyway and then jabbed the air several times for emphasis. Mets win! Yankees lose! Loge 15 goes wild! Niela and Militza and everyone else with a soul is celebrating. And amusingly, I hear on the way home from Suzyn Waldman that the Yankees were grumbling in the visitors’ clubhouse that Armando Benitez celebrated a little too heartily for their tastes, that he was lucky that it was Chili Davis up there. Funny, I thought, I’d been hearing all season how Chili Davis was a godsend at DH for them, what a great guy he was to have in the clubhouse, what a difference he was making for them at the plate. Now Chili Davis, like Roger Clemens, wasn’t True Yankee enough for them.

Maybe we’d see what the Yankees really had the next afternoon. But I should have supposed that even if we’d go out and win perhaps the most thrilling back-and-forth 9-8 game ever played in front of a packed and divided house of snarling partisans — culminating in a most unlikely pinch-hit two-RBI single and play at the plate wherein a journeyman bench player upstages the premier reliever in the sport — that all that would prove is that we got lucky again. But on Friday night, I couldn’t presuppose anything about the next afternoon and its as-yet-unknowable mammoth tilt between good and evil. I didn’t even know that I’d be going to that game, too. On Friday night, all I could know was I had just witnessed on a player’s comps a small classic, Leiter and Benitez and Piazza over Clemens and the rest of them. Yes, I knew that then and I know that now.

Dave Anderson in Sunday’s Times would perfectly capture the sum total of Friday night and what transpired directly on its heels as “the best 24 hours” in Mets history. Bobby V the next afternoon, before the next afternoon became the Matt Franco Game, said of the night before, “I couldn’t sit. I was walking along the dugout, telling guys: ‘This is exciting. This is exciting.'”

Yes, it was. Yes it was. I’m grateful I haven’t completely forgotten about it.

Whether recovering from tonight or prepping for tomorrow, tune in to Mets Weekly on SNY at noon Saturday for a Shea Subway Series retrospective that includes some thoughts on games that aren’t this one from yours truly.

by Greg Prince on 27 June 2008 3:35 pm

The Mets literally stuck it to the Yankees on a glorious July weekend in 1999…hardball, not stickball. Nike distributed these outside Shea just prior to the Matt Franco Game. They brought good luck, even if Matt is not pictured.

by Greg Prince on 26 June 2008 5:00 pm Some months ago I found myself watching Mask, the 1985 movie about the good-natured kid with the terminally misshapen face and Cher for a mother — a pill-popping mother, at that. Its relevance here is the lovable but doomed kid, Rocky (Eric Stoltz), is a big Dodgers fan, so it's a big deal when his grandparents show up and surprise him by producing tickets to that afternoon's game. A kid like Rocky, growing up amid unfortunate circumstances, doesn't get to Dodger Stadium every day, so it's a huge, huge thing that he's suddenly being whisked away to Chavez Ravine to see his favorite team. Other than serving as a device to get him out of the house so Cher can go on a binge, the Dodgers game has no significance in terms of the overall plot. But watching Rocky open the TV listings where his grandfather has cleverly hidden the tickets…it gave me the biggest vicarious thrill. There is nothing like being a kid and finding out you're going to a baseball game.

That's how I've been feeling this week for Dave Murray.

Dave is Mets Guy In Michigan. His circumstances are not at all unfortunate. He's got a grand life in Grand Rapids, writing for a living, raising a family, all, despite missing what he calls “the Homeland,” he could ask for. He doesn't, however, get to Shea Stadium every day. In fact, he hasn't been to Shea Stadium since 1991.

That changes this Saturday. Dave is returning, with his father and his cousin, to the Homeland. Dave is going to his first game at Shea in seventeen years. That it's a Subway Series game and that it's Shea's final season and that Dave, despite rendezvousing with the Mets on the road from time to time since the early '90s, hasn't seen the Mets win in person in any capacity since his previous trip to Shea makes the anticipation all the more tingly.

To me, that is. I know Dave is excited but I find myself excited on behalf of his excitement. I'm more worried about how the Mets will do on Saturday when Dave is going than I am about how they will do on Sunday when I'll be there.

Dave, in addition to being a heckuva human being, is my almost exact demographic contemporary: mid-40s, Nassau County upbringing, Mets fandom forged in the heyday of Tom Terrific, Yankees hater by nature and common sense. This weekend, however, he's a kid, no older than Rocky, whose trip to Dodger Stadium in Mask was a junior high graduation present. Dave, to use a phrase I found myself applying a few weeks ago as I critiqued the latest Mets debacle's effect on my well-being, is not made of cotton candy. He's been around, he knows his stuff, he's no ingénue about baseball or life. But he's not bothering with that on Saturday. He's not cynical or blasé about going to Shea Stadium for a Mets game. He's not 44 in the hours leading up to first pitch. He's 15 or 11 or 9. He's looking at the clock and then peering out the window and then watching the pot to see if it's started to boil and then maybe checking up the chimney. This is Christmas Eve for Dave. When's it gonna get here? When? WHEN?

All week long, Dave's blog has been a countdown to Christmas Morning, Christmas in June. He's making lists of things he's determined to do at Shea, and may Mrs. Payson's ghost have mercy on the overly officious usher or incredibly dopey Yankees fan who gets in his way. Dave's Shea is way better than the real thing. Dave's Shea isn't the Shea he left in 1991. It isn't the one his grandmother took him to on Opening Day in 1975. It's surely not the one the air has hung heavy over in 2008. Dave Murray's Shea Stadium is the one of Dave's wildest dreams. Only a Mets fan has wild dreams involving Shea. Maybe only a Mets Guy In Michigan, deprived of Shea's company for seventeen long years, is capable of truly appreciating and expressing how special a trip to Shea on a Saturday in June will be, regardless of what ensues after the first pitch is thrown.

I find myself so excited that Dave is breaking out of Michigan for the weekend that, like Red in The Shawshank Redemption, I can barely sit still or hold a thought in my head. I think it's the excitement only a Mets fan can feel for another Mets fan. Or maybe it's just that there's nothing like being any age and finding out somebody who really relishes going to a baseball game is, in fact, going to a baseball game.

|

|