The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 9 April 2007 8:19 am If you’re anything like me, you’re starting Your Day of Days.

You’re going to the Home Opener!

You weren’t counting on it, and you were fine without it, but somebody stepped forward from out of the blue and orange to be your eleventh-hour angel and what the hell? It’s Your Day of Days.

You’re waking up with minimal mechanical provocation because you couldn’t sleep anyway.

You’re checking the weather every few minutes on WINS or Channel 61 or by typing in 11368 at weather.com.

You’re debating how many layers to lay on and erring on the side of caution because all the weather reports indicate a Real Feel that won’t top 40.

You’re wondering whether it’s worth breaking out the new orange REYES 7 tee since nobody’s going to see it under all your layers.

You’re wearing the new orange REYES 7 tee because you’ll know it’s there.

You’re spending valuable minutes choosing among sweatshirts, hoodies and warmup jackets.

You’re opting for the royal blue ski cap with the orange NY over any particular cap out of respect for your ears.

You’re bringing a cap in case it’s not all that bad…but not before you weigh the merits of each and every one in contention for the honor of The Cap You Bring To The Home Opener.

You’re packing your game bag with care. Train schedules? Check. Reading glasses? Check. Phone? Check. Bottle of water? Check. Spare bottlecaps? Check. Umbrella? Check — because if you don’t bring it, it will definitely be needed. Pills, ointments, first aid? Check (you hypochondriac). A fistful of napkins? Check — because maybe this is the year they start charging for napkins at Shea. A half-dozen plastic bags? Check — because you have all kinds of organizational compulsions that anybody who saw the way you live would not believe.

You’re stocking extra batteries. For your radio, for Howie, for Tom, for Eddie C. Not for Pat Burrell.

You’re removing your iPod because you don’t really need it…until you remember you may want to hear a song that will put you in the mood…until you remember you’re already in the mood.

You’re bringing your iPod anyway. You’re bringing everything else.

You’re noticing the 2006 and 2005 pocket schedules buried in some crevasse of the bag. Maybe they’re lucky.

You’re leaving your 2006 and 2005 pocket schedules where you found them.

You’re considering what book to shove in there. You’re reading a hardcover that’s just going to weigh you down and you’re going to be too excited on your trip in to read it and you know you’re going to buy the papers at the station and you know you’re going to be leafing through a yearbook and a program on the way home, but it’s a really good book and it’s about baseball, so you shove.

You’re throwing in a magazine just in case your train idles uncomfortably just shy of Valley Stream or Jamaica as it’s been known to do on days that weren’t Your Day of Days.

You’re patting your parka pockets over and over to ensure your gloves are where you they think they are.

You’re stuffing a few ibuprofen and a couple of Pepcid in that extra pants pocket where you keep four pennies (to round out change) just in case your headaches or indigestion get to you.

You’re lugging ample supplies of ibuprofen and Pepcid in your bag, but you don’t have time to unravel your own logic.

You’re leaving your house and considering your car. You’re not crazy enough to decide to drive at the last minute (you hardly ever drive to Shea and doing so today will not spike your confidence in the process) but you’re thinking it sure would be nice to leave the car at the station. Except the station lot will be full since this isn’t a legal holiday.

You’re flinging your bulging bag over your right shoulder, hitching up your jeans and walking the 14 or 15 minutes between your home and your station.

You’re ducking into your station newsstand to buy those papers, maybe a diet soft drink if the lack of sleep is catching up with you, maybe a not altogether stale bagel depending on how much that 14- of 15-minute walk has taken out of you.

You’re withdrawing one of those handy plastic bags for the papers and probably the soda and the bagel and ascending the escalator to the platform, unalone in your particular journey for the first time today, even if you are older than most everybody heading toward your ultimate destination.

You’re feeling a strong breeze. Maybe you should have added a layer between layers.

You’re patting your parka pockets for your gloves. You can’t be too sure.

You’re removing your Metrocard from your wallet and placing it in your pocket for quick access should connections dictate the 7 over the LIRR from Woodside to Shea. Why wait?

You’re glancing at your newspapers’ back pages or sports section front page, a bit disgusted that some other event got more play than yesterday’s or, better yet, today’s Mets game.

You’re sticking a hand in your schlep bag to make sure you can access your reading glasses (with a book, a magazine, three newspapers and several schedules on your person, you don’t want to inadvertently re-enact the Burgess Meredith role in the “Time Enough At Last” episode of The Twilight Zone) and your phone. You decide the phone belongs in one of the parka pockets because if the eleventh-hour angel, who is the reason you’re on the platform with seemingly half of everything you own, needs to reach you, you better be able heed the call.

You’re searching your phone for messages related to work until you realize you’re not going to be of much help to anybody today.

You’re hoping those people who don’t know today is Your Day of Days won’t bother you. This is no way to earn a living, but you can do that any old time. Today is Your Day of Days.

You’re positioning yourself for the train as it arrives, choosing a less crowded car up front versus a more crowded car in the middle even though settling for the middle will deposit you nearer to the stairs to the 7. Right now you’re counting on your Woodside LIRR connection to make that decision moot. Right now you could use a Sandy Alomar to flash you a sign.

You’re plopping yourself into an unoccupied three-seater and for a moment you’re not a Mets fan going to the Home Opener. You’re a commuter plucking his ten-trip ticket out for the conductor and you’re an antisocial animal who spreads out your crap so nobody will sit next to you.

You’re drifting back into your mission once your ticket is punched. Your solitude is breached because there are like eight teenagers with 24 cans of beer whooping it up, but you drown them out not with your iPod (it’s drooped too deep in the schlep bag to be worth fishing out), but with your thoughts.

***

You’re thinking about where you’re going.

You’re thinking that once you set foot inside Shea Stadium, this will mark your 35th consecutive year of making such an entrance.

You’re thinking if you can say you’ve been going anywhere else every year since 1973 and you’re coming up blank.

You’re thinking that your father sold the house you grew up in in 1991 and your sister didn’t move into her current home until 1984 and an insurance plan forced you to switch doctors in 2003, you’ve narrowed it down to a diner on Long Beach Road (a longtime favorite, but there was a stretch there in the late ’90s when you didn’t go at all), a mall in Garden City (your wife’s catalog shopping saved you those trips for a couple of years) and a transpiration hub in Manhattan (you know you missed it entirely that year you stayed at college for the summer semester). Having eliminated the East Bay Diner, Roosevelt Field and Penn Station, you’ve concluded you’ve been going to Shea Stadium longer and more regularly than you’ve been going anywhere in the world.

You’re thinking you’ll mark a 35th consecutive year today and, knock wood, a 36th consecutive year some twelve months from now, and that will be it.

You’re thinking how weird that will be, that Shea Stadium won’t be there anymore after next year.

You’re thinking that Shea’s faults are myriad and that a few more will reveal themselves today but that you want to remain subject to them because it’s Shea.

You’re thinking that it took you the better part of the first thirty years to know Shea intimately, to differentiate substantively between loge and mezzanine, to know which gate gets you to which ramp, which way to cross Roosevelt Avenue before a game versus afterwards, which stand sells what and which men’s room is preferable to which. Now that you’ve got it down cold, you’re left with the equivalent of a Cold War-era map of Europe.

You’re thinking you’re a Kremlinologist about to lose your U.S.S.R.

You’re thinking that Your Day of Days is no day to think about endings. You turn your attention to beginnings.

You’re thinking about how you romanticized the Home Opener long before you ever got close to attending one, how you blew off Hebrew School to watch 1975’s and good thing you did, too, because otherwise you would have missed Tom Seaver besting Steve Carlton, both of them pitching complete games (and you were never going to be a Talmudic scholar no matter how much Hebrew School you didn’t blow off).

You’re thinking about how you skipped a Spanish test in twelfth grade to make it to your first Home Opener, 1981, only to have rain postpone your dream outside Gate D and your Spanish teacher not buy your flimsy excuse of being sick the next day (you were never going to be a Spanish scholar either).

You’re thinking about maybe the greatest Home Opener of them all, 1985’s, the one Gary Carter wins with the tenth-inning home run while you’re a month from graduating college in another state and you’re lapping up wire copy in your school paper’s newsroom and dialing Sportsphone on their dime every five minutes and, when you learn what your new catcher did, you’re high-fiving everybody you’ve turned into a temporary Mets fan that afternoon.

You’re thinking that when you finally broke through the grass ceiling, that when you were at Shea to greet the new season the first time in 1993 that it was everything you imagined it would be, that it was the center of the known universe. The Colorado Rockies were born and Dennis Byrd was walking (they gave him a “Met for life” jersey with No. 90 on it) and Doc, 28 years old and six years removed from cocaine, threw a shutout. It was chilly but it was brilliant.

You’re thinking of your return engagement on a raw Monday afternoon three years later, the tail end of a winter when it snowed three times a week. That day it spit a cold rain and the Mets fell behind Tony LaRussa’s Cardinals 6-0 and the concessions ran out of hot chocolate immediately. But Hundley homered and Gilkey homered and it was 6-3 in the seventh when the kid shortstop who lit up St. Lucie electrified your frigid section of the mezzanine with a throw from his knees to nail Royce Clayton at the plate. The Mets brought home four runs in the bottom of the inning and won 7-6 and what a year 1996 was going to be.

You’re thinking of a much brighter, much warmer — much hotter — Home Opener in March of 1998. March! You stared at that date, March 31, ever since they announced it and prepared to shiver like you never had before, except a heat wave hit New York days before and it was 87 degrees, which was good because the game went on all day, 14 innings, until the Mets (wearing black caps with blue bills for the first time) won on a single to right by Bambi Castillo. Bambi Castillo was now as big a part of Met history as Rey Ordoñez and Doc Gooden and Gary Carter and Tom Seaver and Mr. Ritaccio the Spanish teacher. Home Opener history at least.

You’re thinking how Home Openers became a happy habit over the next four years, how through the good graces of good friends you found your way in Opener after Opener and the Mets won Opener after Opener and you never went home unhappy.

You’re thinking how exciting it was to return to the scene of the crime in 2005, how a new era was plainly underway, even if the old stadium was not in great working order, even if the Home Opener brought out the dope and lout in every other customer, even if pedestrian traffic was a nightmare. Yet it was Your Day of Days and you were so very glad to have witnessed another lidlifting win, your eighth in eight such opportunities.

You’re thinking now that you don’t want to blow it for everyone else, that you hope you can keep this streak going to 9-0, that maybe you should have declined the eleventh-hour invite because maybe you should sit on your perfect 8-0 until you remember records aren’t for sitting on.

You’re thinking, albeit not that hard, about today’s matchup, about John Maine and Cole Hamels, two of the soap operaest names you might imagine (you can just hear Victor Newman threatening he will destroy John Maine and Cole Hamels if it’s the LAST thing he ever does, but you just as soon keep your intermittent Y&R viewership to yourself).

You’re thinking maybe it’s not so bad the Mets got a loss or two out of the way in Atlanta, maybe you don’t want them to be 6-0 and risk it all for the Home Opener, though that’s sort of at odds with your own 8-0 superstitions and you try not to think all that much about records.

You’re thinking instead of what’s driving you here, and you don’t mean the Long Island Rail Road. This is your 39th season as a Mets fan. You never tire of mentioning that you boarded this train in 1969 and you take enormous pride that you never got off.

You’re thinking it’s an accomplishment to have rooted for the Mets as long and hard as you have, yet it never occurred to you to do anything else, so what’s the accomplishment exactly?

You’re thinking once a Mets fan always a Mets fan, even if you know not everybody who’s a Mets fan at this moment has pursued as pure an existence.

You’re thinking you made this choice before you made any other choice of consequence and that it’s a choice you’ve stuck by going on four decades, though you can barely fathom a phrase like “going on four decades” applies to something you remember choosing at the age of six.

You’re thinking you never wavered, that this is who you are above and beyond just about anything else you are and even if you now and then allow yourself to wonder if you’re hopelessly shallow for thinking in such terms, you think in them nonetheless and have no intention of reversing course at this late date.

You’re thinking precious few people have given you more pleasure and happiness than your baseball team has and that nobody has done it over a longer span and that nobody and nothing have plucked at your emotions more than your Mets have. Nobody and nothing ever will.

You’re thinking that though you might be willing to trade for a little righthanded relief help or an honest-to-god slugger to come off the bench in the late innings, you would not trade your lifetime as a Mets fan for anything. Not today on Your Day of Days. Not ever.

You’re thinking that you better make sure you don’t have to change at Jamaica for Woodside lest you be so lost in thought that you wind up at Penn Station and blow the whole day before it truly begins.

***

You’re paying attention to your commute again, staying on to Woodside, exiting, peeking down the Port Washington tracks, deciding between the eastbound LIRR and the 7 and, in not too many minutes, disgorging from one or the other at a stop called Shea Stadium.

You’re elbowing your way through crowds who are clogging the staircases and ramps you wish to negotiate cleanly.

You’re sneering at the red caps with white P’s (there are always a few) and the navy caps with hormonally whack NY’s (there are always a few too many).

You’re looking at your fellow travelers and are amazed at how underdressed so many of them are. It’s 42 freaking degrees!

You’re calculating how many beers and furtive flask sips it takes to compensate for a lack of a coat.

You’re reading the slice of oaktag that declares the supremacy of Jose, David and the Mets in general and looking at the kid who’s toting it and you’re sorry there’s no chance it will show up on TV.

You’re assessing the construction that’s gone on east of Shea all winter and are blown away by the progress. Two years…

You’re keeping an eye out for freebies. Bumperstickers? Placards? Anything that doesn’t require you to fill out a form?

You’re snapping up whatever you can buy outside the park on the slight chance it will sell out by the time you’re inside (you’re haunted by the way those inaugural Mets-Rockies programs flew). Pins…yearbook…program…miscellany items that you try to convince yourself you don’t need but you don’t try all that strenuously.

You’re stuffing this wave of purchases into one of your spare plastic bags (you’re not so crazy now, huh?).

You’re making contact with your eleventh-hour angel. There’s a ticket with your name on it so, without further ado, it’s onto the security line for a halfhearted pawing of your stuff, a pause for a man with a wand to pat you down (you don’t look like you’d cause any trouble, but how is he supposed to know that?), a scan of your magic ducat, a grab of a magnetic schedule and anything else you’re handed and…you’re in!

You’re getting your bearings. The last time you were here, last October via a similar shot-in-the-dark ticket situation, you were a much different bundle of nerves. Then it was one and done. Today it’s 4-2, 156 (yes, 156) to go. But you’re a bundle of nerves anyway.

You’re escalating to your level (though you’re not discounting the possibility that you’re climbing) and you’re reaching your seat and you’re shoving your bags underneath it and you’re sitting down (how these plastic chairs have narrowed since fall; same thing happened last April) and you’re studying the fence for new sponsors, the DiamondVision for new fonts, the field for new players. It’s all new enough to beg the question of what’s with the new park over the fence?

You’re forgetting about the future today. And you’re even putting aside your cherished past. You’ve got a present. You’ve got a Home Opener.

If you’re anything like me, Your Day of Days has arrived.

by Greg Prince on 8 April 2007 11:10 pm The “161-1” winks are no longer valid. And I'd forget the 160-2 scenario based on precedent.

El Duque was outdueled by El Davies, El Andruw was his old octopus self and the inbred Braves foiled the Mets' bid to never, ever fall out of first place again. We seemed to have taken up permanent residence there after the third game of 2006. Now we're in (gasp!) second.

Maybe it's the Islanders' having shotout their way into the playoffs (it was a Melvin Mora week all around in Uniondale), maybe it's the impending premieres of The Sopranos and Entourage, maybe it's that I'm heading out in a few minutes to pick up Indian for dinner, maybe it's knowing Shea glorious Shea opens for business in 18 hours…but I'm not all that bothered.

We're 4-2 from the road. We could have been 6-0 but there was no way we could have been any worse than what we are now. The starting pitching has been acceptable-plus, often golden, since a week ago tonight. Everybody among the regulars has accomplished something lovely so far and most have done more. A little more hitting or a little more bullpen the last two days would have compensated for the shortcomings of one or the other, but it's a long season. They'll both take care of themselves.

When you're good, losing two out of three to your nominal archrivals at your erstwhile burial ground is just one of those things you learn to breathe through.

Beat the Phillies though, OK?

by Greg Prince on 8 April 2007 6:53 pm Yesterday was the first game of the year in which the throw pillows on the couch lived up to their name. With that game-tying line drive intercepted just shy of the end zone (Georgia being SEC country), I threw a pillow clear across the living room.

With that, the 2007 season became real. The f-word that’s neither faith nor fear made its maiden appearance of the year. Welcome back frustration. (There may have been a fourth f-word flung toward the television as well…a lot.)

The moment that made it more unbearable than one L after four W’s should be was the penultimate out of the ninth inning. After Wright singles and Delgado trots to third, Alou comes up. Moises Alou seems like somebody I would want up here. He’s off to a warm start and he’s a proven RBI man. Then Joe Buck tells me Alou is a notorious first-ball hitter.

He is?

Moises Alou has been knocking around the National League since 1990, and knocking around the ball quite effectively. But all these years that he’s been a Pirate, an Expo, a Marlin, an Astro, a Cub and a Jint, I confess that I’d never watched him closely enough to know all his tendencies. He’s a notorious first-ball hitter? Does that mean he’s going to swing at Wickman’s first offering even though he went to 3-and-2 to Beltran before striking him out, 3-and-2 on Delgado before walking him and 3-and-1 on Wright before David’s single?

It does. Moises does Wickman the biggest favor imaginable and swings and pops meekly to center. Instead of working the count and pressuring the closer, there’s only a second pointless out cramping our style.

This was a game the Mets didn’t particularly deserve to win, not the way they fielded, not the way Glavine was pitching, not the way Smoltz outclassed our lineup. But great teams occasionally pocket games they have little business winning. This ninth inning, not unlike the ninth inning of the last Met loss of any consequence, shaped up as a ninth inning in which we could grab a couple runs off the shelf while the gods were out having a smoke.

Nothing doing. One distressing repositioned lineout later, I was left to ponder Alou the way I was forced to ponder Beltran last October 19. I reasoned then if Carlos got this far in his career by not swinging at curves breaking inside then it was ludicrous to demand he change his habits with a pennant on the line. I’d spend the winter reasoning the opposite, too, but that was winter and last year, so never mind that right now. Point is my, your, everybody’s rule is when a pitcher is playing footsie with the strike zone, don’t make it easier on him. When it’s first and third and you’re down by two runs with one out in the ninth, DON’T SWING AT THE FIRST PITCH!

But if this is how Moises Alou has become Moises Alou, maybe he sees something that I don’t and maybe he was right to swing when he did. Despite being aware of Moises Alou for 17 years, I realize I don’t really know him yet. And that you don’t really know a man until he becomes a Met.

by Jason Fry on 8 April 2007 12:50 am Last night, luxuriating in a 4-0 start, I debated noting that the Mets hadn’t trailed in an inning in 2007. I decided not to — as I wrote to my co-blogger, “Nah. We’ll point it out the first time it’s true.”

Today it was true — part of an unasked-for matching set that included 2007’s first errors, first boneheaded plays, first substantive bad luck and that first disgruntled feeling that follows losing a baseball game.

Smoltz-Glavine II wasn’t a classic along the lines of Smoltz-Pedro two years ago, or even Smoltz-Glavine I. It was long, grinding and slightly tedious, not just for the sloppy plays and the lousy conditions, but for the slow-motion demolition of the whole thing. I did a double-take realizing the Braves had batted around in that dreadful sixth, because it was more a bunch of minor bad things happening than the kind of pummeling that ought to come with Batman-style WHAMs and BIFFs and SOCKs on the screen. Double, single, line out, walk, ball dropped by Green, sac fly, walk, Baltimore chop 50 feet high off the plate, flyout. Ugh. Blame the heavens for Edgar Renteria’s plate job, but Green’s extra out sticks in the craw. For the life of me I cannot understand why baseball players persist in putting their sunglasses atop the brim of their caps on sunny days. (Or leaving them there once the folly of doing so has been demonstrated.)

I suppose you could take heart in a patient ninth inning that came just short. I wound up shaking my head, amused and annoyed at what a kick in the ass baseball can be. David Wright stealing second, putting us one hit away from a tie game and a re-evaluation of that revitalized Braves bullpen, looked like a heads-up play and a vapor-lock by Bob Wickman. Too bad the stolen base let Craig Wilson come off the line, leaving him in perfect position to snare Green’s liner just before it zipped by him. (Talk about it not being Wright’s day.)

“The line drives are caught, the squibbles go for base hits,” Rod Kanehl once said. “It’s an unfair game.” Green and Edgar Renteria can attest to that. On the other hand, the baseball gods don’t give out favors to those who don’t put their sunglasses over their eyes. Nor, I suppose, should they.

by Greg Prince on 7 April 2007 6:39 pm These last couple of years the trademark of the Atlanta Braves has been a preponderance of young, homegrown players who were born and bred in Georgia: Jeff Francoeur, Brian McCann, Chuck James, Macay McBride, Kyle Davies.

Think maybe the inbreeding has caught up with them?

The family elders — Cox, Smoltz and those dirty Jones boys — still preside over the clan and I keep hearing about this new, improved bullpen that’s nothing like all those previously new, improved bullpens, but the Braves don’t look like The Braves to me anymore. Turner Field doesn’t look like Turner Field to me anymore. They’re just another team in just another ballpark on just another road trip. They could beat us today. They could beat us tomorrow. Anybody could beat anybody twice. That still wouldn’t make them The Braves. That’s over. That’s not four games talking. That’s 166 and counting.

Chris Woodward…Tyler Yates…Roger McDowell…the Braves don’t poach outside the family as well as they used to either.

by Jason Fry on 7 April 2007 3:54 am Opponents' fans, as New York Mets bloggers we would like to remind you to come to the game early. Like you, we like nothing better than to bask in all the joys a few hours at the ballpark can bring: The sights and sounds of batting practice, that first bite of a hot dog, warbling the Star-Spangled Banner, having your buddy hand you a cold beer, watching your kids lick stray cotton-candy fibers off their fingers, appreciating the arcs and lines of the ball going around the infield while the pitcher warms up, and of course just relaxing in the sight of all that green grass. We love all these things too, and we want to ensure that you and your guests get to enjoy them. So please — make sure you have enough time to savor your surroundings. Because by the second or third time through the New York Mets' batting order, your time at the park will no longer be so enjoyable. By then it may hurt quite a bit.

Between St. Louis and now Atlanta, we've wrecked two bitter rivals' home openers and probably driven 75,000 Braves and Cardinals fans out of their seats and home early. (Kudos to former President Carter and Rosalynn for not being among them.) Tonight, before the napkins and plastic bags had stopped flying from first base to third base and the baseballs had stopped flying from Met bats to all points, Turner Field was a gallery of portraits of misery. Some of those were our own: John Maine in his knit cap, with nothing whatsoever to do but try to stay near the heater; Damion Easley huddled on the bench, now the lone Opening Day Met not to take the field; and Carlos Delgado standing at first with his arms folded over his chest, looking like he'd almost rather be somewhere else, if not for the hits and the runs and the winning. Fortunately there were more-wretched expressions on the other side: Roger McDowell, looking increasingly grim each time we see him (sorry, Roger); poor Brayan Pena chasing a week's worth of errant balls in a miserable inning-plus of catching Macay McBride; the entire Braves' defense during that endless 8th; and of course Bobby Cox. But then Bobby Cox always looks that way. Joe Torre may have perfected looking imperturbable until the final out of the World Series, but Bobby Cox always looks like a guy who accidentally sat in a puddle and now doesn't see how moving would improve things.

Rick Peterson, on the other hand, looked about as happy as a man spending several hours outside in a biting wind could look. As he should. For proof of the Jacket's value, look no further than the inaugural 2007 starts of John Maine and Oliver Perez. Not the results, though those were wonderful, but the approach that led to those results. Maine blitzed the Cardinals with an arsenal that looked totally different than anything he had last year, when you admired his guts but worried about his vulnerability to the long ball and what would happen once the league saw him a few times. Maine has worked to remake himself as a pitcher, and while it's just one start, that one start should be viewed as the hard-earned sequel to a spring training spent wisely. Perez, to my eyes, wasn't as good tonight as his numbers might indicate — in the middle innings his release point wobbled around and his focus seemed to wander, and he benefited from a Braves team that didn't seem inclined to let a pitch go by. But that said, his game plan, too, looked different. His release point was mostly consistent. His focus was mostly on Lo Duca, home plate and the batter. And he seemed able to rein himself in when he needed to. (And hell, aggressive Braves or not, he didn't walk anybody.) Those are big steps in remaking him not into what he once briefly was, but into an entirely new pitcher who should have a longer lease on life.

On the offensive side, it's easy to admire Jose Reyes triples and Carlos Beltran doubles. (And I do, believe me.) But the two at-bats I found most cheering were from Shawn Green and Jose Valentin in the eighth, when it was all over but the shouting. Up 10 runs on a cold night, Green worked a walk. Up 10 runs on a cold night, Valentin hit a little ground ball and raced toward first like a dog after a dropped Quarter Pounder — and almost beat out a hit. Neither at-bat led to a run tonight, and they were all but lost amid the blue-and-orange Blitzkrieg. But as with the continuing maturation of Maine and the rebuilding of Perez, those at-bats were signs of success in what might be the hardest part of baseball for these incredibly gifted athletes: How to bear down mentally time after time after time, whatever the score and the situation. The at-bats that get you wins in the dogfights and in the dog days of August don't happen in a vacuum — they date back to doing the right thing in games that are already won on cold nights in April.

by Greg Prince on 6 April 2007 9:17 pm When their season began, they were nobody. When it ended, they were somebody. If it’s the first Friday of the month, then we’re remembering them in this special 1997 Mets edition of Flashback Friday.

Ten years, seven Fridays. This is one of them.

If these Julio Franco times, when ballplayer age is such an elastic yardstick, could be transported back to 1962, it’s not inconceivable that the Mets would have selected Jackie Robinson in the expansion draft. Robinson turned 43 that January, more than five years younger than Franco is now. Had health and choice permitted him to have continued playing a theoretical sixth season beyond his actual retirement, he was exactly who the Mets would have drafted. He was an old Dodger. We already know Walter O’Malley wouldn’t have hung onto him. Hell, Walter O’Malley traded him to the Giants after the 1956 season for Dick Littlefield. Robinson quit the game rather than join his archrivals. He had other opportunities outside baseball and 38 was very old then. Very old for baseball, very old for someone who had lived as much of a life as Robinson had.

Really, it’s a ludicrous hypothetical. Jackie Robinson wasn’t about to become a Met in 1962. He would have to wait 35 years for that honor.

April 15 marks 10 years since the night Jackie Robinson’s 42 went up on the left field wall at Shea Stadium. It went out of circulation just about everywhere that night, an overwhelming honor for a single player, one deemed appropriate by Commissioner Bud Selig who told a sellout crowd that “no single person is bigger than the game of baseball…no one except for Jackie Robinson.” With that, the number was retired by the Mets, by the Rockies, by the Orioles, by franchises whose players shunned and mocked and harassed and spiked the man of the hour, by everybody. It was a bold and grand gesture by a commissioner not especially noted for effective leadership, an unprecedented tribute to the man who changed baseball forever exactly 50 years earlier.

I was at Shea for the occasion. I had no intention of missing it, no matter how cold it was going to be. It was a great night even if one can, to this day, sift through and quibble with the decision Selig made.

• Was baseball guilt-tripping all over itself on that cold (very cold, extremely cold) night in 1997, attempting with one mighty swing to compensate for all it got dead wrong before 1947, all it was still getting wrong by 1987 when the Al Campanis “necessities” debacle exploded all over Nightline?

Probably to some extent, but what’s the point of acknowledging a misdeed if you’re not going to go all out in correcting it? Jackie Robinson absolutely “changed the face of baseball and America” on April 15, 1947, as President Bill Clinton, the first chief executive to visit Shea while in office, said in the on-field ceremonies. Baseball can’t undo its pre-1947 segregationist past, but it can shine a light on all that was done to move forward in the hope that it — and America — would keep moving forward. Vince Coleman infamously professed ignorance regarding Robinson’s life story. With 42 in plain sight everywhere and with the sport invoking his name, his number and his legacy every April 15 since, no ballplayer of any color would ever again be able to get far in his chosen profession unaware of the one person who did more than any other to shape its contours. It doesn’t seem unreasonable that you know a little bit about the field in which you’ve opted to pursue a career for yourself.

The fans would learn, too. We can always stand to learn a little more about our game.

• If Jackie Robinson rated his number’s retirement, what about Babe Ruth’s 3 for the man who saved and/or popularized baseball? What about Roberto Clemente, whose 21 represents humanity at its pinnacle and engenders a legacy all its own?

What about them? 3 is retired by the Yankees, 21 by the Pirates. But weren’t they bigger than the game, too? On one level, sure. Ruth (despite the team for whom he played and the house he allegedly built) deserves to be remembered as the biggest star baseball ever knew and will ever know. But there were ballplayers before him. He pulled the sport out of the shadow of doubt cast by the Black Sox scandal, but chances were there’d be ballplayers after him.

Clemente died one of the most noble civilian deaths imaginable, rushing relief supplies to Nicaragua after that country’s devastating 1972 earthquake. That alone is worthy of memorial — such as that embodied by the Roberto Clemente Award presented every October to the Major Leaguer who combines outstanding play on the field with devoted work in the community, the most recent recipient of which was our own Carlos Delgado (who wears 21). Clemente was one of the first Latin players in the big leagues, the first superstar among them. He certainly blazed trails, he certainly suffered indignities on account of his heritage…like Robinson — and after Robinson. Chronologically speaking, Jackie carved the first and most sustained path for the times in which we would come to live. In that sense, that makes Robinson bigger than Ruth, bigger than Clemente, bigger than everybody, bigger than the game.

• If 42 means so much, why take it out of circulation?

This is the toughest question to answer as a baseball fan. For that one Arctic night in 1997, you couldn’t have asked for a better way to focus the world’s attention on Robinson’s deeds and meaning. Remember that the number-retirement was a surprise. We knew the commissioner and the president and Rachel Robinson would be at Shea for what was officially billed as the Jackie Robinson 50th Anniversary Celebration (there were rumors that the newly green-jacketed Tiger Woods would fly in to represent the next generation, but he declined the last-minute invite). There were commemorative “Breaking Barriers” patches on everybody’s uniform sleeves that year. There were special sections in all the papers. The Interboro Parkway became the Jackie Robinson Parkway that week. Anheuser-Busch replaced its usual Budweiser ad on the scoreboard with one praising the all-time Dodger (which made the well-intentioned referral to his having been a “giant” rather unfortunate; Rob Emproto rolled his eyes and suggested to me they just get it over with and “call him a Giant Yankee”). But until Selig made his remarks about Jackie Robinson being bigger than the game and then directed our gaze toward left field, we didn’t know 42 was being removed from active duty.

We discuss retired numbers the way other cultures ponder sainthood. The Hall of Fame may be understood as the ultimate baseball honor, but Cooperstown is out of our hands. The retirement of a player’s number is something closer to our hearts and thus somehow more sacred. Our team can do something about it. We understand the soul of our ballclub and our ballplayers. We know damn well the level of their celestial significance in our universe and we tell each other all the time. We use as our currency in this discourse the uniform number. How great, how important, how eternal was this guy to us? Or that guy? He was so great, so important, so eternal, that you just have to retire his number. Nobody who decides these matters asks us to weigh in but we do. It’s the one vote to which we’re sure we’re all entitled.

With 42 retired, that vote was taken away. No, Ron Taylor, Ron Hodges and Roger McDowell weren’t candidates to join Casey Stengel, Gil Hodges and Tom Seaver in the Met numerical pantheon, but now neither would be Butch Huskey, who had worn 42 since 1995 as his own salute to Robinson. Huskey was wearing 42 when the game started that night. Here after five innings, as the ceremonies proceeded (only Jackie Robinson was big enough to interrupt at length a game in progress), he and we were told his number was done.

Well, not exactly. Selig said 42 could stay on the backs of those who already had it, grandfathered in for those were paying personal tribute to Robinson. That described mainly Mo Vaughn of the Red Sox and Butch Huskey of the Mets. (The ruling also left 42 undisturbed on the back of the Yankees’ new closer Mariano Rivera.) Huskey would wear 42 through 1998 until he was traded to Seattle, and that was assumed to be it among 42ish Mets. But it was born again when Vaughn became a Met in 2002 but finished up with him the next year (though Bob Murphy was presented with a framed Mets 42 jersey to represent the totality of his years behind the mic in 2003 and a few nitpickers somehow managed to find this insulting to Robinson.)

Syracuse University’s football team long maintained a fascinating tradition. It didn’t retire Jim Brown’s 44 because it considered the issuing of it to a deserving Orangeman an honor, a tradition to be carried on. Ernie Davis won a Heisman wearing 44 after Brown matriculated his way to the pros. Floyd Little wore 44 after Davis. Number 44 was such a big deal at Syracuse that they changed the school’s ZIP code from 13210 to 13244. The tradition ceased in 2005 when 44 was finally raised to the Carrier Dome rafters. SU athletic director Daryl Gross reasoned “if you can’t take 44 off the table, then you’re just never going to retire a jersey.”

True that. But still…

Syracuse had a nice thing going and, more germane to Jackie Robinson, what Vaughn and Huskey had done was stirring. At least once every series that Vaughn, a superstar, came to bat for Boston, the announcer for Boston’s opponent would explain why he wore 42. As Huskey became more established, word was getting out on his and his back’s behalf. These were two players right in our midst who decided to be the living, breathing embodiment of American history, who decided that the game was bigger than themselves (and in Vaughn’s and Huskey’s cases, that was extra large indeed).

That would be over with the commissioner’s decision. Now 42 would be on the wall at Shea and in some form or fashion in every ballpark. It was in danger of becoming wallpaper. Everybody would pay homage, therefore nobody would pay homage. Washington’s Birthday and Lincoln’s Birthday had become, in a manner of baseball speaking, Presidents Day.

Ten years later, Bud Selig has made another decision concerning 42. This April 15, a week from Sunday, the number comes out of retirement for a day. One uniform on every team can bear the 4 and the 2 (except on the Dodgers, where everybody will wear them, and the A’s, who will allow two players and one coach to share them). On the Mets it will be the skipper Willie Randolph, New York’s first African-American manager. He’s thrilled:

It’s a tremendous honor. When I heard that today, they were joking with me about who would wear it, and I said, “I’m going to fight whoever’s got it.” It’s an honor to be even mentioned with his name. It’s going to be a special day for me to be able to wear number 42.

You can’t fight the manager and you can’t argue with his logic. Ken Griffey, who switched to 42 on 4/15/97 and convinced Selig to take this step on 4/15/07, will don the number for the Reds. Jimmy Rollins will shut up long enough to take it for the Phillies. Jesse Barfield will be 42 on the Indians, as Coco Crisp will do on the Red Sox. You can’t argue with them either.

But Dave Murray raises a point of contention on Mets Guy in Michigan concerning what Willie said about 42:

I’d love the quote even more if it came from David Wright. Or Greg Maddux. Or Chipper Jones. Or Randy Johnson. Or Jim Thome. Or Pronk [Travis Hafner]. Or Curt Schilling. Or any other star who happens to be white.

All of them benefited greatly the day Jackie Robinson bravely stepped on that field, not just the black players.

Amen.

It’s hard to overlook the practicality of Jackie Robinson’s debut. Where once baseball was segregated, it was, by his hand, integrated. It was no longer Whites Only. Of course the impact was most direct on black players and, logic would follow, other non-white players. But we all benefit from knowing each other as people, not races. We all benefit from Robinson and 42, all Americans, all baseball fans.

And the Mets? As noted, Jackie was out of baseball and with Chock Full O’ Nuts as a vice president by 1962. He went into the Hall of Fame that summer. Except for Old Timers Days, when he wore a Dodgers uniform, Robinson didn’t forge any particular bond with the Mets. It was the 50th Anniversary night in his honor, taking place on Met ground — with the no-longer-Brooklyn Dodgers as visitors — that cemented his posthumous place in Mets history. Mrs. Robinson has returned regularly since April 15, 1997. The Wilpons have supported the Jackie Robinson Foundation enthusiastically. And if you’re not sure why there will be a rotunda devoted to Jackie Robinson at Citi Field in 2009, you can probably trace it back to that shivering night a dozen years earlier. Fred Wilpon may have grown up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, but it was that salute to Jackie that seemed to have sparked his determination to reinvent Ebbets Field in Flushing. If you’re still wondering why the next home of the Mets will be all Bummed out, Jackie Robinson Night is a night worth remembering.

As for who has played for the Mets these 46 seasons of their existence — specifically who was not white — you can’t help but credit Jackie Robinson for ensuring their opportunity. 1962 wasn’t all that long after 1947 and it was but three years after 1959, when Pumpsie Green (a future Met himself) became the first player on the last team, the Red Sox, to employ a black player. Ensuring integrated accommodations for the first Met Spring Training in St. Petersburg were still an issue in 1962. Ed Charles, seven years before ascending to poet laureate of the Miracle Mets, debuted as a Kansas City Athletic in 1962 at the age of 28, same age as Robinson in 1947. Pretty similar reason, too: most organizations kept a pretty strict quota on the number of black players it would promote. Ed Charles had knocked around the Brave system since 1952. It took him ten years to climb the ladder.

Did Robinson make it possible for Green and Charles to make it to the Majors? Sure. What about, as a piece in the Post put it in April 1997, Lance Johnson and Bernard Gilkey and Butch Huskey? That seemed a bit far-fetched to me. It was fifty years later; if not Robinson, wouldn’t have somebody else have come along eventually? Was not America moving inexorably in the direction of integrating its institutions?

Maybe. But sometimes a move needs a shove, and it was definitely Jackie Robinson’s (and Branch Rickey’s) role to administer it. In the previously recommended Best New York Sports Arguments, Peter Handrinos makes the case that there was only one Robinson, only one man who actually did what he did — and maybe nobody else could have done it as effectively if he hadn’t done it when he did it:

What would have happened if Jackie Robinson failed? Robinson would have been dismissed. He would have been labeled an outside activist and/or hothead. Undoubtedly, the editors of The Sporting News (“Baseball’s Bible”) would have concluded they were vindicated in saying blacks didn’t have the intelligence or inner fortitude to succeed on the highest level. And estimated 60% of the Major Leaguers of 1947 were white southerners who’d never known anything but racial segregation, and every one of them, including high-profile players like Enos Slaughter, Dixie Walker and Bobby Bragan, would have been treated as heroes for calling anti-Robinson boycotts. Those who had stood with Robinson, the Pee Wee Reeses of the world, would have been the marginalized ones.

Handrinos admits his worst-case scenario is speculative but the prevailing circumstances of 1947 (Brown v. Board of Education wouldn’t reach the Supreme Court until 1954) back up his assertions. As he points out, even with Robinson’s successes, college coaching titans like Adolph Rupp and Bear Bryant kept integration at bay for another two decades…and that was with Jackie Robinson’s remarkable career having changed so much.

Changes couldn’t have been denied forever, but Robinson’s failure would have deferred them indefinitely.

On April 15, 1997, on a cold Queens night, those changes were instead celebrated. A number was posted on a wall. A legacy was extended. A team became one with a player who never played for them. A sellout crowd — the most racially mixed crowd I ever sat among at Shea Stadium — cheered. Cheered Jackie Robinson. Cheered Rachel Robinson. Cheered Bill Clinton and Bud Selig. And cheered Toby Borland.

One player was bigger than the game, but the game did go on. And it was a damn fine one, easy to recognize because to that point in 1997, the Mets had played virtually none like that.

We opened on the West Coast, which was unusual but was supposed to be the great new thing. Cold-weather teams would go west and come home when it got warmer. The plan didn’t work well at all. The Mets went 3-6 on The Coast, looking lost and anemic. They came home to open on a Saturday. Why a Saturday? Because the defending world champion Yankees, who also opened out west, would be raising their 23rd flag on Friday afternoon and the Mets didn’t want to compete for attention. They postponed their opening a day, but rain postponed it again to Sunday. A Home Opener doubleheader. Little pomp. Dire circumstances. Not quite 22,000 saw the Mets drop two to the Giants. Twelve-thousand more watched another loss to San Francisco Monday. We were 3-9 entering Jackie Robinson Night.

This would be our de facto opener, then. The Mets unveiled what were supposed to be their Sunday unis: snow white pants and shirts, no pinstripes and, for reasons unclear, white caps with blue bills. Armando Reynoso must have liked the look because he threw five shutout innings before Selig & Co. took over the field. Once the number was retired, it was back to baseball. Bobby Valentine wouldn’t send out a starter on such a frigid night (yeah, it really warmed up while we were in California) after such a long delay, so out to the mound went Borland. And Borland authored four scoreless frames for his first and only Met save.

Cold but worth it. Mets 5 Dodgers 0, Lance Johnson with four ribbies. Our record rose to 4-9. It marked the beginning of a brief run of .500 ball by the Mets, from whom nobody expected anything remotely that good. Two losses in Montreal sent us to 8-14 as of April 26, but there were a couple of positive developments in the interim. John Olerud, dumped on us by Toronto, was hitting .360. Rick Reed, the former replacement player (he was introduced that way every time he pitched like it was the law), had moved from the pen to the rotation out of desperation, and was posting an ERA in the low ones. Pete Harnisch had gone down to panic attacks on Opening Day, Jason Isringhausen was lost to a tuberculosis scare and a fractured right wrist and the Flammable Four relievers — Ricardo Jordan, Yorkis Perez, Barry Manuel and, despite his Robinson Night save, Toby Borland — were burning themselves out of jobs, but maybe the Mets wouldn’t be quite as bad as we thought they’d be entering the season.

Mike Francesa doubted there were really 54,047 paying fans for the Jackie Robinson celebration. The Mets had distributed blocks of tickets to school and community groups, either out of altruism or to ensure themselves a full house. After he and Christopher Russo cackled over the total attendance, Francesa magnanimously allowed the Mets their numbers. This would be, he proclaimed, all the Mets would have to hang their white hats on in 1997 anyway.

Not so fast there Mikey…

Next Friday: We could’ve been something else altogether.

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2007 10:50 pm If it weren't for who was sweeping them, I'd be overjoyed that the Phillies just got beaten three straight.

Since it was against the Braves, I'll settle for joyed.

Three games. Just three games. Chuck Dressen insisted the Giants was dead in 1951 after many more games and he was revealed quite incorrect in his assessment. But c'mon, you gotta revel in the Rollins mystique unraveling so very quickly. Team to beat? Insert your own suitable retort regarding beatings applied to his team here.

It's a damn shame Philly and Atlanta can't both be 0-3 right now. For what it's worth, the Braves came close to throwing it all away in the ninth. Up 8-2, Macay McBride and Chad Poronto (both of whom sound like they were called in to provide backup to Ponch and Jon on CHiPS) walked five Phils, letting in two runs and leaving the bases loaded for Carlos Ruiz who popped up on the first and final pitch from Rafael Soriano.

Confession: I barely know who any of the players mentioned in the above paragraph are but I hate each of them already. I hate the Braves a little more based on 7:35 tomorrow night, but the Phillies have caught up fast. Well, they came close to catching up — loaded the bases and everything.

Phillies or Braves? Braves or Phillies? ¿Quién es mas detestable? There is no wrong answer. The ground can't cause a fumble but it can, with my blessing, open up and swallow both teams whole, piling their flailing carcasses (if indeed carcasses can flail) willy-nilly over those belonging to the Defending World Champions.

Antipathy for your rivals in spring…this sure beats staring out the window and waiting for hate.

by Jason Fry on 5 April 2007 1:29 pm They even shot Tommy in the face so his mother couldn't give him an open casket at his funeral.

— Henry Hill, Goodfellas

Absent a handy black hole or Superman determined to blow off Kal-El and pull Lois Lane out of a ditch, you can't turn back time. All the Clydesdales in the world won't put those rings back in their cases or put the ball back in Adam Wainwright's hand and give Carlos Beltran another chance. It's over. What happens in April 2007 won't change what happened in 2006.

But it might have something to do with what happens in 2007.

Anticipating Braden Looper, last night I told Emily I wouldn't be satisfied with anything less than 10 earned in a third of an inning against our former closer, mock-“Jose” chanter and embodiment of 2004's horrors and 2005's frustrations. That didn't happen, and I didn't hear Looper escape mostly unscathed — I was at Varsity Letters, where I'm proud to report that the crowd was mostly Met fans and raucous cheers greeted the news that the Mets had finally broken out on top.

With Varsity Letters complete, I headed into the night and turned on my trusty radio for the first time in 2007, enjoying the brief stumble of remembering what button does what, since the labels have long since worn away. Fortunately I figured it out, had batteries, and got Howie and Tom on just in time to hear Julio Franco elevate the score from comfortable to ridiculous. And accompanying it was a wonderful sound: Cardinals fans booing.

Booing? In St. Louis? But I thought they didn't do that! I thought they cheered and cheered and cheered, when they weren't busy carrying newly acquired utility infielders through the streets on their shoulders or building housing for the indigent while offering each other very nice compliments. Naaaah. You know what Cardinals fans do? They boo and mock-cheer beleaguered relievers and leave stadiums in droves when things don't go their way even when it's just the third game of the new season and they're once again celebrating a brand-new world championship. Can “The Best Fans in Baseball” now join the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus on the list of things we gently explain to our children are very nice ideas but not actually real?

Of course, a fan's patience is tested when you've just been torched 20-2 in a three-game sweep, never held a lead for a half-inning, seen your bullpen and outfield exposed, and watched your superstar go 1 for 10. A fan's patience is tested when the final game of that three-game sweep is an absolutely pitiless beatdown of the variety that more-sheltered Midwesterners assume happens to anyone unwise enough to set foot in New York City.

Cardinals fans are fine fans compared to everything but their own myth. But last night wasn't the night for being reasonable — last night was the night for glee at the pain of others. When Jose Reyes took third and drew Yadier F. Molina's ire, I clapped madly. (This was around Lafayette and Canal, and people looked at me anxiously.) When Reyes came home on the slow roller to Rolen, which also probably didn't make Y. Fucking Molina happy, I yelled and pumped my fist. When Wright's long drive to open the ninth was caught, I moaned in disappointment. (This was on the Brooklyn Bridge, so I had no audience but myself.) This was a closed-casket game — no quarter and check your mercy at the door.

In April 1986 the Mets, then 7-3 and rounding into form, went to St. Louis with fans still muttering about being edged out by the Cardinals in 1985. They beat the Cards 5-4 in 10, then administered a 9-0 pasting, then won 4-3 and 5-3 for a four-game sweep. The Mets didn't retroactively go to the playoffs in 1985 because of that, but in 1986 Whitey Herzog and Company were never a factor again. A lot has changed since then — we're no longer division rivals and have just four games against each other remaining, so we won't have a lot to do with the Cardinals' fate one way or another. And a regular-season beatdown means nothing, as all of us still cringing over the 1988 NLCS remember all too well. But while the past is past, I think it's safe to say we've made our point about the present — and sent a clear signal about the future.

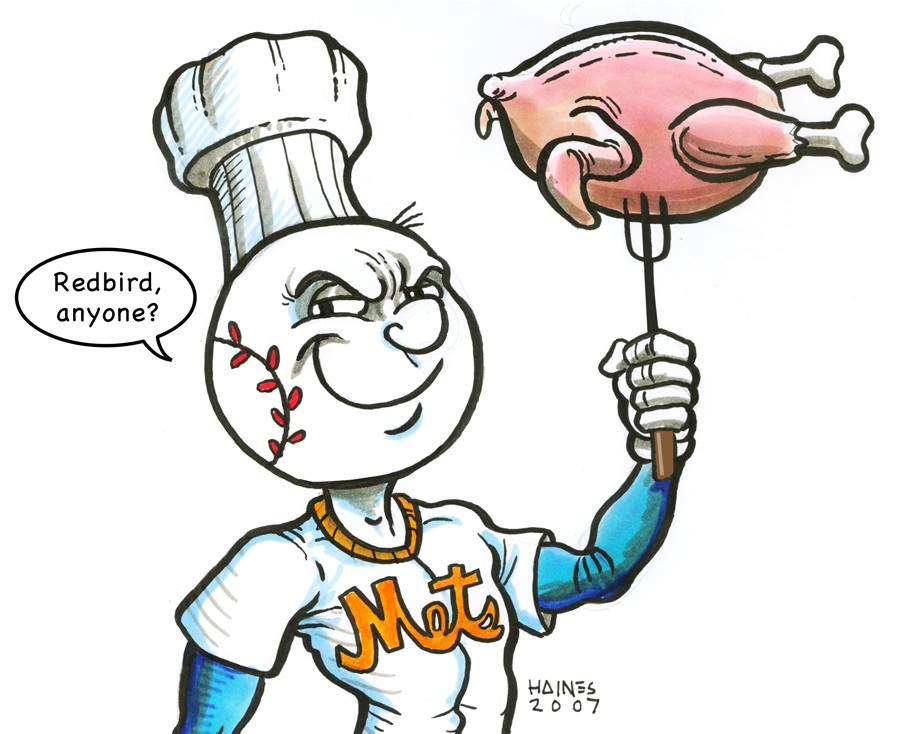

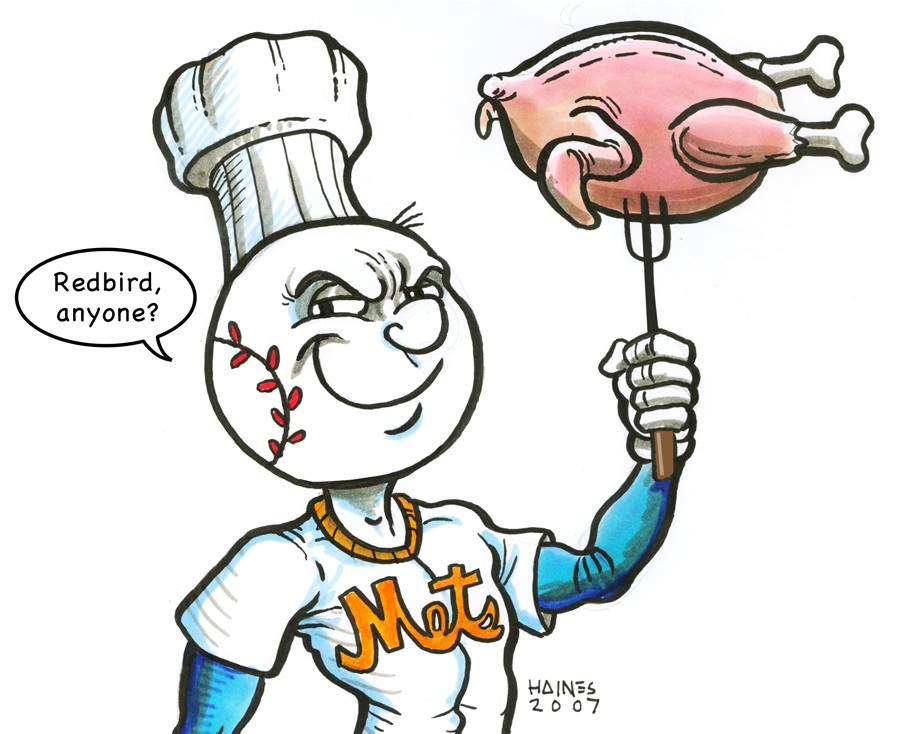

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2007 4:00 am

Mr. Met has skewered himself a Cardinal. Dig in everybody!

Roasting of Redbird courtesy of Zed Duck Studios…so much for birds of a feather.

|

|