The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 6 April 2007 9:17 pm When their season began, they were nobody. When it ended, they were somebody. If it’s the first Friday of the month, then we’re remembering them in this special 1997 Mets edition of Flashback Friday.

Ten years, seven Fridays. This is one of them.

If these Julio Franco times, when ballplayer age is such an elastic yardstick, could be transported back to 1962, it’s not inconceivable that the Mets would have selected Jackie Robinson in the expansion draft. Robinson turned 43 that January, more than five years younger than Franco is now. Had health and choice permitted him to have continued playing a theoretical sixth season beyond his actual retirement, he was exactly who the Mets would have drafted. He was an old Dodger. We already know Walter O’Malley wouldn’t have hung onto him. Hell, Walter O’Malley traded him to the Giants after the 1956 season for Dick Littlefield. Robinson quit the game rather than join his archrivals. He had other opportunities outside baseball and 38 was very old then. Very old for baseball, very old for someone who had lived as much of a life as Robinson had.

Really, it’s a ludicrous hypothetical. Jackie Robinson wasn’t about to become a Met in 1962. He would have to wait 35 years for that honor.

April 15 marks 10 years since the night Jackie Robinson’s 42 went up on the left field wall at Shea Stadium. It went out of circulation just about everywhere that night, an overwhelming honor for a single player, one deemed appropriate by Commissioner Bud Selig who told a sellout crowd that “no single person is bigger than the game of baseball…no one except for Jackie Robinson.” With that, the number was retired by the Mets, by the Rockies, by the Orioles, by franchises whose players shunned and mocked and harassed and spiked the man of the hour, by everybody. It was a bold and grand gesture by a commissioner not especially noted for effective leadership, an unprecedented tribute to the man who changed baseball forever exactly 50 years earlier.

I was at Shea for the occasion. I had no intention of missing it, no matter how cold it was going to be. It was a great night even if one can, to this day, sift through and quibble with the decision Selig made.

• Was baseball guilt-tripping all over itself on that cold (very cold, extremely cold) night in 1997, attempting with one mighty swing to compensate for all it got dead wrong before 1947, all it was still getting wrong by 1987 when the Al Campanis “necessities” debacle exploded all over Nightline?

Probably to some extent, but what’s the point of acknowledging a misdeed if you’re not going to go all out in correcting it? Jackie Robinson absolutely “changed the face of baseball and America” on April 15, 1947, as President Bill Clinton, the first chief executive to visit Shea while in office, said in the on-field ceremonies. Baseball can’t undo its pre-1947 segregationist past, but it can shine a light on all that was done to move forward in the hope that it — and America — would keep moving forward. Vince Coleman infamously professed ignorance regarding Robinson’s life story. With 42 in plain sight everywhere and with the sport invoking his name, his number and his legacy every April 15 since, no ballplayer of any color would ever again be able to get far in his chosen profession unaware of the one person who did more than any other to shape its contours. It doesn’t seem unreasonable that you know a little bit about the field in which you’ve opted to pursue a career for yourself.

The fans would learn, too. We can always stand to learn a little more about our game.

• If Jackie Robinson rated his number’s retirement, what about Babe Ruth’s 3 for the man who saved and/or popularized baseball? What about Roberto Clemente, whose 21 represents humanity at its pinnacle and engenders a legacy all its own?

What about them? 3 is retired by the Yankees, 21 by the Pirates. But weren’t they bigger than the game, too? On one level, sure. Ruth (despite the team for whom he played and the house he allegedly built) deserves to be remembered as the biggest star baseball ever knew and will ever know. But there were ballplayers before him. He pulled the sport out of the shadow of doubt cast by the Black Sox scandal, but chances were there’d be ballplayers after him.

Clemente died one of the most noble civilian deaths imaginable, rushing relief supplies to Nicaragua after that country’s devastating 1972 earthquake. That alone is worthy of memorial — such as that embodied by the Roberto Clemente Award presented every October to the Major Leaguer who combines outstanding play on the field with devoted work in the community, the most recent recipient of which was our own Carlos Delgado (who wears 21). Clemente was one of the first Latin players in the big leagues, the first superstar among them. He certainly blazed trails, he certainly suffered indignities on account of his heritage…like Robinson — and after Robinson. Chronologically speaking, Jackie carved the first and most sustained path for the times in which we would come to live. In that sense, that makes Robinson bigger than Ruth, bigger than Clemente, bigger than everybody, bigger than the game.

• If 42 means so much, why take it out of circulation?

This is the toughest question to answer as a baseball fan. For that one Arctic night in 1997, you couldn’t have asked for a better way to focus the world’s attention on Robinson’s deeds and meaning. Remember that the number-retirement was a surprise. We knew the commissioner and the president and Rachel Robinson would be at Shea for what was officially billed as the Jackie Robinson 50th Anniversary Celebration (there were rumors that the newly green-jacketed Tiger Woods would fly in to represent the next generation, but he declined the last-minute invite). There were commemorative “Breaking Barriers” patches on everybody’s uniform sleeves that year. There were special sections in all the papers. The Interboro Parkway became the Jackie Robinson Parkway that week. Anheuser-Busch replaced its usual Budweiser ad on the scoreboard with one praising the all-time Dodger (which made the well-intentioned referral to his having been a “giant” rather unfortunate; Rob Emproto rolled his eyes and suggested to me they just get it over with and “call him a Giant Yankee”). But until Selig made his remarks about Jackie Robinson being bigger than the game and then directed our gaze toward left field, we didn’t know 42 was being removed from active duty.

We discuss retired numbers the way other cultures ponder sainthood. The Hall of Fame may be understood as the ultimate baseball honor, but Cooperstown is out of our hands. The retirement of a player’s number is something closer to our hearts and thus somehow more sacred. Our team can do something about it. We understand the soul of our ballclub and our ballplayers. We know damn well the level of their celestial significance in our universe and we tell each other all the time. We use as our currency in this discourse the uniform number. How great, how important, how eternal was this guy to us? Or that guy? He was so great, so important, so eternal, that you just have to retire his number. Nobody who decides these matters asks us to weigh in but we do. It’s the one vote to which we’re sure we’re all entitled.

With 42 retired, that vote was taken away. No, Ron Taylor, Ron Hodges and Roger McDowell weren’t candidates to join Casey Stengel, Gil Hodges and Tom Seaver in the Met numerical pantheon, but now neither would be Butch Huskey, who had worn 42 since 1995 as his own salute to Robinson. Huskey was wearing 42 when the game started that night. Here after five innings, as the ceremonies proceeded (only Jackie Robinson was big enough to interrupt at length a game in progress), he and we were told his number was done.

Well, not exactly. Selig said 42 could stay on the backs of those who already had it, grandfathered in for those were paying personal tribute to Robinson. That described mainly Mo Vaughn of the Red Sox and Butch Huskey of the Mets. (The ruling also left 42 undisturbed on the back of the Yankees’ new closer Mariano Rivera.) Huskey would wear 42 through 1998 until he was traded to Seattle, and that was assumed to be it among 42ish Mets. But it was born again when Vaughn became a Met in 2002 but finished up with him the next year (though Bob Murphy was presented with a framed Mets 42 jersey to represent the totality of his years behind the mic in 2003 and a few nitpickers somehow managed to find this insulting to Robinson.)

Syracuse University’s football team long maintained a fascinating tradition. It didn’t retire Jim Brown’s 44 because it considered the issuing of it to a deserving Orangeman an honor, a tradition to be carried on. Ernie Davis won a Heisman wearing 44 after Brown matriculated his way to the pros. Floyd Little wore 44 after Davis. Number 44 was such a big deal at Syracuse that they changed the school’s ZIP code from 13210 to 13244. The tradition ceased in 2005 when 44 was finally raised to the Carrier Dome rafters. SU athletic director Daryl Gross reasoned “if you can’t take 44 off the table, then you’re just never going to retire a jersey.”

True that. But still…

Syracuse had a nice thing going and, more germane to Jackie Robinson, what Vaughn and Huskey had done was stirring. At least once every series that Vaughn, a superstar, came to bat for Boston, the announcer for Boston’s opponent would explain why he wore 42. As Huskey became more established, word was getting out on his and his back’s behalf. These were two players right in our midst who decided to be the living, breathing embodiment of American history, who decided that the game was bigger than themselves (and in Vaughn’s and Huskey’s cases, that was extra large indeed).

That would be over with the commissioner’s decision. Now 42 would be on the wall at Shea and in some form or fashion in every ballpark. It was in danger of becoming wallpaper. Everybody would pay homage, therefore nobody would pay homage. Washington’s Birthday and Lincoln’s Birthday had become, in a manner of baseball speaking, Presidents Day.

Ten years later, Bud Selig has made another decision concerning 42. This April 15, a week from Sunday, the number comes out of retirement for a day. One uniform on every team can bear the 4 and the 2 (except on the Dodgers, where everybody will wear them, and the A’s, who will allow two players and one coach to share them). On the Mets it will be the skipper Willie Randolph, New York’s first African-American manager. He’s thrilled:

It’s a tremendous honor. When I heard that today, they were joking with me about who would wear it, and I said, “I’m going to fight whoever’s got it.” It’s an honor to be even mentioned with his name. It’s going to be a special day for me to be able to wear number 42.

You can’t fight the manager and you can’t argue with his logic. Ken Griffey, who switched to 42 on 4/15/97 and convinced Selig to take this step on 4/15/07, will don the number for the Reds. Jimmy Rollins will shut up long enough to take it for the Phillies. Jesse Barfield will be 42 on the Indians, as Coco Crisp will do on the Red Sox. You can’t argue with them either.

But Dave Murray raises a point of contention on Mets Guy in Michigan concerning what Willie said about 42:

I’d love the quote even more if it came from David Wright. Or Greg Maddux. Or Chipper Jones. Or Randy Johnson. Or Jim Thome. Or Pronk [Travis Hafner]. Or Curt Schilling. Or any other star who happens to be white.

All of them benefited greatly the day Jackie Robinson bravely stepped on that field, not just the black players.

Amen.

It’s hard to overlook the practicality of Jackie Robinson’s debut. Where once baseball was segregated, it was, by his hand, integrated. It was no longer Whites Only. Of course the impact was most direct on black players and, logic would follow, other non-white players. But we all benefit from knowing each other as people, not races. We all benefit from Robinson and 42, all Americans, all baseball fans.

And the Mets? As noted, Jackie was out of baseball and with Chock Full O’ Nuts as a vice president by 1962. He went into the Hall of Fame that summer. Except for Old Timers Days, when he wore a Dodgers uniform, Robinson didn’t forge any particular bond with the Mets. It was the 50th Anniversary night in his honor, taking place on Met ground — with the no-longer-Brooklyn Dodgers as visitors — that cemented his posthumous place in Mets history. Mrs. Robinson has returned regularly since April 15, 1997. The Wilpons have supported the Jackie Robinson Foundation enthusiastically. And if you’re not sure why there will be a rotunda devoted to Jackie Robinson at Citi Field in 2009, you can probably trace it back to that shivering night a dozen years earlier. Fred Wilpon may have grown up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, but it was that salute to Jackie that seemed to have sparked his determination to reinvent Ebbets Field in Flushing. If you’re still wondering why the next home of the Mets will be all Bummed out, Jackie Robinson Night is a night worth remembering.

As for who has played for the Mets these 46 seasons of their existence — specifically who was not white — you can’t help but credit Jackie Robinson for ensuring their opportunity. 1962 wasn’t all that long after 1947 and it was but three years after 1959, when Pumpsie Green (a future Met himself) became the first player on the last team, the Red Sox, to employ a black player. Ensuring integrated accommodations for the first Met Spring Training in St. Petersburg were still an issue in 1962. Ed Charles, seven years before ascending to poet laureate of the Miracle Mets, debuted as a Kansas City Athletic in 1962 at the age of 28, same age as Robinson in 1947. Pretty similar reason, too: most organizations kept a pretty strict quota on the number of black players it would promote. Ed Charles had knocked around the Brave system since 1952. It took him ten years to climb the ladder.

Did Robinson make it possible for Green and Charles to make it to the Majors? Sure. What about, as a piece in the Post put it in April 1997, Lance Johnson and Bernard Gilkey and Butch Huskey? That seemed a bit far-fetched to me. It was fifty years later; if not Robinson, wouldn’t have somebody else have come along eventually? Was not America moving inexorably in the direction of integrating its institutions?

Maybe. But sometimes a move needs a shove, and it was definitely Jackie Robinson’s (and Branch Rickey’s) role to administer it. In the previously recommended Best New York Sports Arguments, Peter Handrinos makes the case that there was only one Robinson, only one man who actually did what he did — and maybe nobody else could have done it as effectively if he hadn’t done it when he did it:

What would have happened if Jackie Robinson failed? Robinson would have been dismissed. He would have been labeled an outside activist and/or hothead. Undoubtedly, the editors of The Sporting News (“Baseball’s Bible”) would have concluded they were vindicated in saying blacks didn’t have the intelligence or inner fortitude to succeed on the highest level. And estimated 60% of the Major Leaguers of 1947 were white southerners who’d never known anything but racial segregation, and every one of them, including high-profile players like Enos Slaughter, Dixie Walker and Bobby Bragan, would have been treated as heroes for calling anti-Robinson boycotts. Those who had stood with Robinson, the Pee Wee Reeses of the world, would have been the marginalized ones.

Handrinos admits his worst-case scenario is speculative but the prevailing circumstances of 1947 (Brown v. Board of Education wouldn’t reach the Supreme Court until 1954) back up his assertions. As he points out, even with Robinson’s successes, college coaching titans like Adolph Rupp and Bear Bryant kept integration at bay for another two decades…and that was with Jackie Robinson’s remarkable career having changed so much.

Changes couldn’t have been denied forever, but Robinson’s failure would have deferred them indefinitely.

On April 15, 1997, on a cold Queens night, those changes were instead celebrated. A number was posted on a wall. A legacy was extended. A team became one with a player who never played for them. A sellout crowd — the most racially mixed crowd I ever sat among at Shea Stadium — cheered. Cheered Jackie Robinson. Cheered Rachel Robinson. Cheered Bill Clinton and Bud Selig. And cheered Toby Borland.

One player was bigger than the game, but the game did go on. And it was a damn fine one, easy to recognize because to that point in 1997, the Mets had played virtually none like that.

We opened on the West Coast, which was unusual but was supposed to be the great new thing. Cold-weather teams would go west and come home when it got warmer. The plan didn’t work well at all. The Mets went 3-6 on The Coast, looking lost and anemic. They came home to open on a Saturday. Why a Saturday? Because the defending world champion Yankees, who also opened out west, would be raising their 23rd flag on Friday afternoon and the Mets didn’t want to compete for attention. They postponed their opening a day, but rain postponed it again to Sunday. A Home Opener doubleheader. Little pomp. Dire circumstances. Not quite 22,000 saw the Mets drop two to the Giants. Twelve-thousand more watched another loss to San Francisco Monday. We were 3-9 entering Jackie Robinson Night.

This would be our de facto opener, then. The Mets unveiled what were supposed to be their Sunday unis: snow white pants and shirts, no pinstripes and, for reasons unclear, white caps with blue bills. Armando Reynoso must have liked the look because he threw five shutout innings before Selig & Co. took over the field. Once the number was retired, it was back to baseball. Bobby Valentine wouldn’t send out a starter on such a frigid night (yeah, it really warmed up while we were in California) after such a long delay, so out to the mound went Borland. And Borland authored four scoreless frames for his first and only Met save.

Cold but worth it. Mets 5 Dodgers 0, Lance Johnson with four ribbies. Our record rose to 4-9. It marked the beginning of a brief run of .500 ball by the Mets, from whom nobody expected anything remotely that good. Two losses in Montreal sent us to 8-14 as of April 26, but there were a couple of positive developments in the interim. John Olerud, dumped on us by Toronto, was hitting .360. Rick Reed, the former replacement player (he was introduced that way every time he pitched like it was the law), had moved from the pen to the rotation out of desperation, and was posting an ERA in the low ones. Pete Harnisch had gone down to panic attacks on Opening Day, Jason Isringhausen was lost to a tuberculosis scare and a fractured right wrist and the Flammable Four relievers — Ricardo Jordan, Yorkis Perez, Barry Manuel and, despite his Robinson Night save, Toby Borland — were burning themselves out of jobs, but maybe the Mets wouldn’t be quite as bad as we thought they’d be entering the season.

Mike Francesa doubted there were really 54,047 paying fans for the Jackie Robinson celebration. The Mets had distributed blocks of tickets to school and community groups, either out of altruism or to ensure themselves a full house. After he and Christopher Russo cackled over the total attendance, Francesa magnanimously allowed the Mets their numbers. This would be, he proclaimed, all the Mets would have to hang their white hats on in 1997 anyway.

Not so fast there Mikey…

Next Friday: We could’ve been something else altogether.

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2007 10:50 pm If it weren't for who was sweeping them, I'd be overjoyed that the Phillies just got beaten three straight.

Since it was against the Braves, I'll settle for joyed.

Three games. Just three games. Chuck Dressen insisted the Giants was dead in 1951 after many more games and he was revealed quite incorrect in his assessment. But c'mon, you gotta revel in the Rollins mystique unraveling so very quickly. Team to beat? Insert your own suitable retort regarding beatings applied to his team here.

It's a damn shame Philly and Atlanta can't both be 0-3 right now. For what it's worth, the Braves came close to throwing it all away in the ninth. Up 8-2, Macay McBride and Chad Poronto (both of whom sound like they were called in to provide backup to Ponch and Jon on CHiPS) walked five Phils, letting in two runs and leaving the bases loaded for Carlos Ruiz who popped up on the first and final pitch from Rafael Soriano.

Confession: I barely know who any of the players mentioned in the above paragraph are but I hate each of them already. I hate the Braves a little more based on 7:35 tomorrow night, but the Phillies have caught up fast. Well, they came close to catching up — loaded the bases and everything.

Phillies or Braves? Braves or Phillies? ¿Quién es mas detestable? There is no wrong answer. The ground can't cause a fumble but it can, with my blessing, open up and swallow both teams whole, piling their flailing carcasses (if indeed carcasses can flail) willy-nilly over those belonging to the Defending World Champions.

Antipathy for your rivals in spring…this sure beats staring out the window and waiting for hate.

by Jason Fry on 5 April 2007 1:29 pm They even shot Tommy in the face so his mother couldn't give him an open casket at his funeral.

— Henry Hill, Goodfellas

Absent a handy black hole or Superman determined to blow off Kal-El and pull Lois Lane out of a ditch, you can't turn back time. All the Clydesdales in the world won't put those rings back in their cases or put the ball back in Adam Wainwright's hand and give Carlos Beltran another chance. It's over. What happens in April 2007 won't change what happened in 2006.

But it might have something to do with what happens in 2007.

Anticipating Braden Looper, last night I told Emily I wouldn't be satisfied with anything less than 10 earned in a third of an inning against our former closer, mock-“Jose” chanter and embodiment of 2004's horrors and 2005's frustrations. That didn't happen, and I didn't hear Looper escape mostly unscathed — I was at Varsity Letters, where I'm proud to report that the crowd was mostly Met fans and raucous cheers greeted the news that the Mets had finally broken out on top.

With Varsity Letters complete, I headed into the night and turned on my trusty radio for the first time in 2007, enjoying the brief stumble of remembering what button does what, since the labels have long since worn away. Fortunately I figured it out, had batteries, and got Howie and Tom on just in time to hear Julio Franco elevate the score from comfortable to ridiculous. And accompanying it was a wonderful sound: Cardinals fans booing.

Booing? In St. Louis? But I thought they didn't do that! I thought they cheered and cheered and cheered, when they weren't busy carrying newly acquired utility infielders through the streets on their shoulders or building housing for the indigent while offering each other very nice compliments. Naaaah. You know what Cardinals fans do? They boo and mock-cheer beleaguered relievers and leave stadiums in droves when things don't go their way even when it's just the third game of the new season and they're once again celebrating a brand-new world championship. Can “The Best Fans in Baseball” now join the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus on the list of things we gently explain to our children are very nice ideas but not actually real?

Of course, a fan's patience is tested when you've just been torched 20-2 in a three-game sweep, never held a lead for a half-inning, seen your bullpen and outfield exposed, and watched your superstar go 1 for 10. A fan's patience is tested when the final game of that three-game sweep is an absolutely pitiless beatdown of the variety that more-sheltered Midwesterners assume happens to anyone unwise enough to set foot in New York City.

Cardinals fans are fine fans compared to everything but their own myth. But last night wasn't the night for being reasonable — last night was the night for glee at the pain of others. When Jose Reyes took third and drew Yadier F. Molina's ire, I clapped madly. (This was around Lafayette and Canal, and people looked at me anxiously.) When Reyes came home on the slow roller to Rolen, which also probably didn't make Y. Fucking Molina happy, I yelled and pumped my fist. When Wright's long drive to open the ninth was caught, I moaned in disappointment. (This was on the Brooklyn Bridge, so I had no audience but myself.) This was a closed-casket game — no quarter and check your mercy at the door.

In April 1986 the Mets, then 7-3 and rounding into form, went to St. Louis with fans still muttering about being edged out by the Cardinals in 1985. They beat the Cards 5-4 in 10, then administered a 9-0 pasting, then won 4-3 and 5-3 for a four-game sweep. The Mets didn't retroactively go to the playoffs in 1985 because of that, but in 1986 Whitey Herzog and Company were never a factor again. A lot has changed since then — we're no longer division rivals and have just four games against each other remaining, so we won't have a lot to do with the Cardinals' fate one way or another. And a regular-season beatdown means nothing, as all of us still cringing over the 1988 NLCS remember all too well. But while the past is past, I think it's safe to say we've made our point about the present — and sent a clear signal about the future.

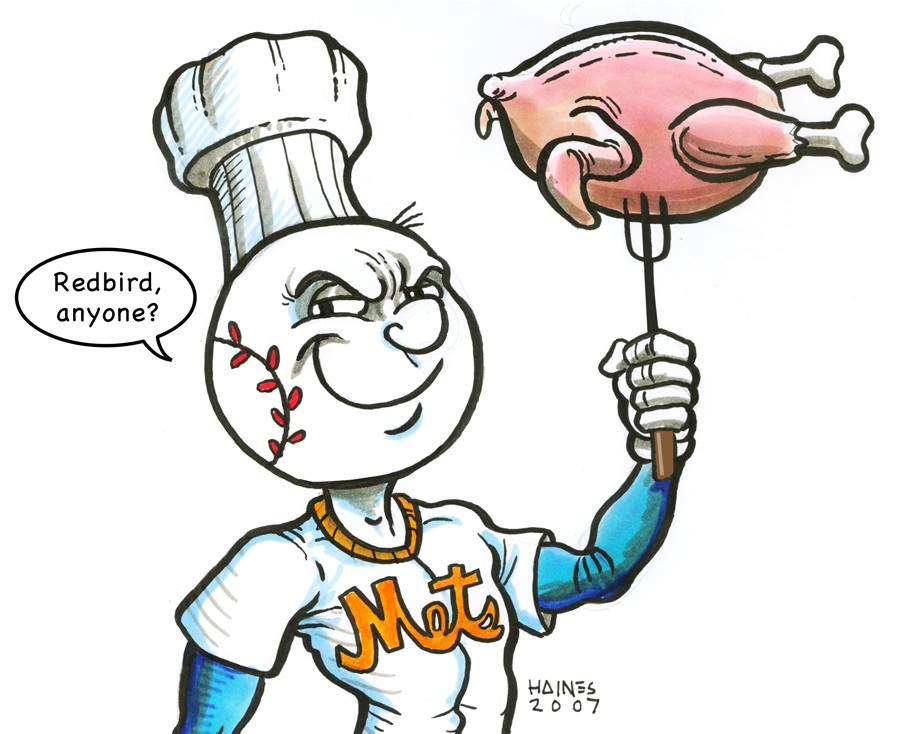

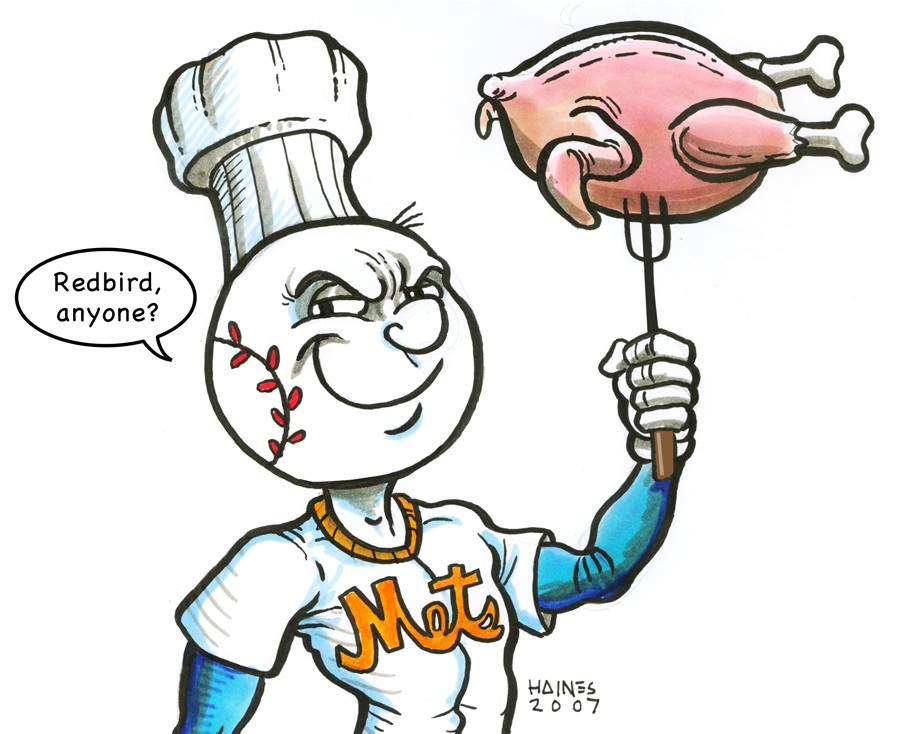

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2007 4:00 am

Mr. Met has skewered himself a Cardinal. Dig in everybody!

Roasting of Redbird courtesy of Zed Duck Studios…so much for birds of a feather.

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2007 3:18 am My hair may be in need of a trim, but I can think of some birds whose wings have definitely been clipped.

Goodbye 2006 World Champion Cardinals. Goodbye Busch Stadium and your lights that blind only the home team's outfielders. Goodbye Stan The Man and Scott Spiezio's dad and the chick with the earmuffs. Goodbye to rings and banners and orgies of self-congratulation. Goodbye to overly acrobatic Jim Edmonds and recast Braden Looper and .100-hitting Albert Pujols and earthbound Yadier Molina and Shades LaRussa.

Goodbye to all that.

Hello 2007 Mets. Hello you big, beautiful defending National League East champions. Hello home run power, surehanded fielding and starting pitching that's never in doubt.

Goodbye 0-3 Cardinals. See you in St. Louie, screwy.

Hello 3-0 Mets.

Hello Carlos Beltran who may take a strike three now and then but won't be caught lookin' no more. Hello Jose Reyes whose homer was nice but I was kind of, almost rooting for a triple. Hello Paul Lo Duca, batting .385 after tonight. Hello suspect Shawn Green, posting a .333 after three games. Hello nearly flawless John Maine, even better than barely touched El Duque who was even better than highly competent Tom Glavine.

Hello Moises and Ambiorix and Aaron the other. Hello all you new Mets. Hello all you old Mets. Hello Julio Franco who knows where to send a fly ball — right at Preston Wilson.

Hello everybody. Hello this year. Hello first place, a half-game lead over Atlanta, one ahead of Florida, 2-1/2 over the Rollinses. Is it too early to keep track? Not if these games count. And they do.

The world is three games old. This wasn't revenge. This was this year…is this year. It couldn't have commenced any better.

by Greg Prince on 4 April 2007 9:38 pm Quick question for anyone who frequents barbershops: Does anybody actually talk baseball where you get your hair cut? I’ve been hearing all my life about guys sitting around barbershops mulling the state of the world, particularly baseball. It’s never happened to me.

Never.

I went to the same barber, Mario, for 21 years, from 1974 to 1995. Never once did Mario engage me in baseball talk. It’s not like I didn’t give him clues, like wearing a Mets jacket and — because my hair was so unruly by the time I rolled in to see him — a Mets cap. But nothin’. Our entire two-decade relationship was amiable but rather limited.

Howyoudoonmyfrien’?

Fine. How are you?

I’m fine. Howyoufamily?

They’re good.

[A specific inquiry regarding one of my parents or my sister’s marriage]?

He’s/she’s/it’s good.

The haircut would proceed without comment. Other guys in other chairs chatted. Mario did a little crosschat with those barbers and those customers. Me and he, despite our longstanding relationship, never had more than two dozen words for each other. We always smiled, but then went shtum. It was never weirder than when we showed up at the same wedding — my friend married his partner’s daughter for a couple of months — and we greeted each other warmly before lapsing into absolutely nothing to say. Other than there being no scissors, no comb and no tall bottle of blue-green liquid on a counter, it was pretty much like all our transactions.

When the silent haircuts were finished, he’d joke about how much better I looked now (the joke part was what I looked like when I came in), I thanked and paid him, he’d urge me to send my regards home, perhaps ask whenyoudaddycominin? and that was that.

Satisfying enough from a folliclesque standpoint. But not one “how about those Mets?” To which you might say, so? Maybe he wasn’t a Mets fan. He probably wasn’t. Except I remember distinctly before Game One of the 1988 NLCS going into get a haircut because I had gone in to get a haircut before Game One of the 1986 NLCS. And in ’88 there was a kid, probably in his teens, getting a haircut from Mario before me and he was a Mets fan and was getting all kind of Mets inquiries from my barber. Mind you I was in the same jacket and cap as I had been two years earlier when I received not a nibble of baseball acknowledgement. Then it was par for the course. Now I was vexed.

This is it, I thought. This is my chance. Mario’s into it. The Mets fan teen is done. My turn. Mario and I exchange pleasantries, we have the haircut, we finish up, he wishes me well and then I hit him with “you know, I came in here before the playoffs started two years ago and the Mets won the World Series, so I figure this will be good luck.”

He smiled and nodded and said goodbye.

NOTHING! DAMN!

This barber shop was run by Italian men who were big soccer fans. Every four years during the World Cup they had TVs blazing. The rest of the time, it wasn’t all that sports-crazed. Except my friend Fred also went to this shop, had a different barber, Dom, and swears Dom consistently engaged him in baseball talk. About the Mets even. Fred was barely cognizant of the Mets.

Me? I got nothing but a haircut.

I hate getting haircuts. I’ve hated getting them since what I’m told was my second haircut when I was two. The first one I sat through calmly. The second one I went nuts, running around George’s Madison Avenue Barber Shop which was on Park Avenue (or Park Street…they never could keep that straight) in Long Beach. I don’t remember the first one. I do remember the second one. Perhaps I’m subconsciously expecting a replay of the second one every time I put off a badly needed haircut as I seem to be doing now. I think I reacted violently in 1965 because I was subject to George trimming my sideburns with that electric contraption they use and a pinch on my right cheek when he was done. “No machine, no pinch on cheek” was my insistence to my parents. They thought it cute. George thought it cute. I was serious.

No machine. No pinch on cheek. Got that?

George gave way to Leo, a nice German man. Leo cut my hair from the time I was, I’ll say, three until I was about ten. Then my mother got it in her head that I needed to have my hair styled at Andre’s. The place stank of hairspray and low-fat frozen yogurt. The haircuts weren’t particularly stylish either. A year later I wound up with Mario. He, like George, like Leo, like the stylist — some machine, no pinch on cheek, no baseball.

Since my 21-year barber retired to Florida, I’ve drifted from chair to chair, settling in for a year or two here or there sometimes but never wanting to get attached like I was to Mario. When Mario left town, it was tough going. Now I leave them before they leave me. But I’m still waiting for that baseball talk that might win me over for the long haul, that baseball talk I’m always hearing about. Bill Gallo from the Daily News insists it goes on full-force where he gets his hair cut (then again, Bill Gallo insists it’s 1942). The last haircut I got, up the street from where I live, there was some lively chatter…into cellphones. One guy was lying to his wife about where he was. Swore he was picking up his car at the garage and would be home soon. Somebody else was getting the number of the shop wrong. It was right there in neon in the window. Look at it in the mirror, I was thinking, you’ll see it plainly. But he kept giving it out wrong and wondered why somebody couldn’t reach him. He needed the number because his cell was on the fritz. I’ll bet he didn’t know how to turn it on.

One barber where I used to live had a series of those neat Bill Goff prints on the wall, the ones of ballparks and ballplayers. But we never talked baseball. Once he told me he was having a tooth problem. I recommended a dentist. He said he wasn’t interested in helping make some Jewish lady — the dentist’s wife, in his mind — rich. If he didn’t give such good haircuts I would have been more offended and stopped going sooner.

Eight springs ago my hair was as out of control as it is now. I was in the city on a Saturday and had no chance of getting back to my neighborhood barber with the vaguely anti-Semitic leanings that hadn’t yet revealed themselves before he closed, so I stopped in at a midtown hotel barbershop. It was an expensive haircut by my suburban standards, $25, but it was there and it got done. As I was paying, I noticed an obituary from the Times taped to the wall above the register. It was M. Donald Grant’s.

“Did he get his hair cut here?” I asked, pointing to the obit.

“Oh yes,” the barber said with some reverence. “He was such a nice man.”

Maybe I’m better off not talking baseball in barbershops after all.

by Greg Prince on 4 April 2007 3:36 am Here's a piece of paper. It says the Mets have taken eight of twelve from the St. Louis Cardinals. That's absolutely true on paper. Now crumple up the paper and discard it at once. It's best not to think about it.

Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez pitched and hit his way to victory. He sure looked calf-ready and unarthritic, the kind of pitcher you would have wanted in an enormous series at a different time of year. It's best not to think about it.

Did we mention El Duque hit his way to victory? With the bases loaded and two out in the sixth, he poked one down the third base line just when it looked as if a golden sixth-inning scoring opportunity would evaporate on sight. That's clutch hitting. It's good to think about it in terms of this particular game. Otherwise, it's best not to think about it.

Aargh…as in we aargh in a brand new season but as long as we're playing hmmm over there, it's impossible to watch any of this without thinking of any of that. And if you don't know what “that” is, well, congratulations on having become a Mets fan 51 hours ago — or recovering so nicely from that lobotomy you got for Christmas.

I didn't see any rings handed out, but then again I didn't need any motivation. Molina…Edmonds…that fucker with the landing strip on his chin…about the only thing that didn't call up October 2006 was the repeated reminder to myself that this is April 2007 and in April 2007, despite having played nobody at all except for the St. Louis Cardinals in any competition of consequence since October 12, we are two and oh. They are oh and two. We are sharp. They are ragged. We are winning. They are losing.

They have rings, very specific rings, that we don't. It's best not to think about it.

by Greg Prince on 3 April 2007 6:14 pm

Let’s Go Mets is the Quintessential Mets Thing, having prevailed in the 2007 March Metness tournament by edging The Happy Recap in a spirited Metropolitan Championship game Monday night.

Having outlasted 63 worthy opponents in the March Metness Field of 64, there’s nothing left to say except…Let’s Go Mets!

by Greg Prince on 3 April 2007 5:56 pm One of a great city’s functions is to serve as a repository of memory. We need to be a place that preserves not just happy times and grand buildings, but those memories that affect us on the deepest level.

—Francis Mirrone, New York historian

Monday’s night’s March Metness championship game was an affair to remember, from the bows taken by the distinguished Mets alumni — Don Aase, Rick Sweet, Larry Elliot, Tom Filer, Ken Sanders, Sammy Taylor and Sammy Drake — who loaned their good names to the festivities all the way to the presentation of awards at tournament’s end.

And in between?

The Metropolitan Championship Game

Let’s Go Mets (1) vs The Happy Recap (1)

Does it get any more Metsian than this? The cry of Mets fans and the voice of Mets fans. Nothing could be any more quintessentially Miraculous, Magical, Believable or Amazin’. But one has to be a bit more so than the other. That’s why they hold March Metness

Surprisingly, we see the action unfold with a display of drawbacks by each entrant. Flaws? These two? Hard to fathom, but they are on record.

Bob Murphy: Unbridled optimism in the face of a stretch of 64-98 seasons could get to you a little…in later years he blew fly balls, had them being caught when going out and going out when being caught…he blew smoke in his partner’s face, not a good thing for either of them…once referred to Al Leiter as Larry Dierker…hosted Bowling For Dollars, though that could be taken as a plus in some quarters.

Let’s Go Mets: Bastardized by other, unworthy teams in other sports and other leagues…occasionally corrupted via four-syllable mispronunciation by younger generation that has taken its cues from bad “Let’s Go” examples set elsewhere…too often foisted on Shea crowd by electronic means when it’s best left to arise organically from Shea crowd itself…co-opted for use in “Let’s Go Mets!” song and video — a.k.a. “Let’s Go Mets Go!” — though that could be taken as a plus in some quarters.

Yet those foibles did not stop either LGM or THR from being seeded in the No. 1 slots in their respective regions and it certainly didn’t slow them down as they raced through five matchups apiece to arrive at the Metropolitan Championship game. When you get right down to it, there is no way any true blue and orange Mets fan can find any real fault with either of them. There is only good to be had.

The Happy Recap is, to be precise, what Bob Murphy promised following a Mets win. He didn’t make a big thing of it. He never teased it through the broadcast, didn’t say “wow, the Mets are up seven to one, so you know there will be a Happy Recap when this game is over.” Can you imagine Murph being that self-serving? The fans and the game were his constituency. If the Mets lost, there was no mention of a Happy Recap. If they won, there would be a quick word that we (“we,” not “I”) would be back with The Happy Recap after this message. When Murph returned from commercial, it was all about what Cleon Jones or Jerry Koosman or Del Unser or Craig Swan or Steve Henderson or The Man They Call Nails Lenny Dykstra or David Arthur Kingman or Ronnie Darling or John Olerud or you name him did. It was about the players and the Mets and the final score here at Shea Stadium, the New York Mets seven, the San Diego Padres one; our next broadcast will be…

That was it. That was The Happy Recap. A short summation, the runs, the hits, the errors and a signoff. Yet that little tail applied to the end of an afternoon or evening became a signature like nobody else’s in Mets broadcast history. Nobody ever played up The Happy Recap per se. We all just knew about it. We tapped it out like Murph Code. For forty-two years those were our words to root by, our goal to strive for. And when Bob Murphy stopped announcing for good in 2003, they stayed with us.

That’s the power of the local announcer, the local radio announcer. Murph did TV, too, from 1962 through 1981, rotating back and forth between booths with Ralph Kiner, Lindsey Nelson, Steve Albert and, briefly, Art Shamsky, but it was Frank Cashen’s genius to assign him to permanent wireless duty in 1982. It was seen as a demotion of sorts in those days. From the invention of television, television was the glamour medium of our time. Stars were on TV. Home run-hitting, Cadillac-driving Ralph Kiner was on TV.

But somebody forgot to tell baseball. Baseball never stopped being at its best on the radio. We were realizing that all over again in the 1980s as a generation that had grown up smuggling a million transistors under a million blankets told its stories. Television could show us much. Radio could tell it all. That was Bob Murphy’s genius. He painted the word picture, the best picture you could have for a baseball game. The man didn’t conduct a talk show from behind a WHN or WFAN microphone. He told you what was going on on the field. He told you who was warming up in the bullpen. He told you who the manager had left on his bench. He did it in a way that kept you engaged when the game was dragging and in a manner that kept you riveted when the game was bursting at the seams. He never discounted the possibility of a Mets comeback, which was darn thoughtful of him.

Bob Murphy clicked with a mass of New Yorkers despite — no, because — he was most un-New Yorkish. Forty-two years on the job and he never picked up a vocal inflection to indicate this was home for more than half his life. Blessedly he never betrayed an ounce of the native cynicism either. Whatever negative thoughts Murph may have brought to the ballpark he put aside when the light went on. Bob Murphy knew he wasn’t granted hour after hour of airtime to air his grievances. He was there to bring us Mets baseball.

To bring us hope.

And weren’t we a most receptive audience for his signal?

It is perhaps some cosmic coincidence that hope and Mets each contain four letters. You usually hear “four-letter word” and you think the worst. Not with hope and, 24 of 45 losing campaigns notwithstanding, not with Mets. The 46th year of New York Mets baseball has commenced and here we are once more, hopeful as ever, maybe more hopeful than we’ve ever been. We slip out of winter and into the season — the only season that counts — and we assume our identity all over again. We nurtured it as best we could without a game in front of us but that was theory. Baseball season in all its in-progress actuality is what reaffirms why we exist in the realm we choose to exist.

Why? To be in such a state that we are compelled to type or print or think or mumble or, most appropriately, scream from the top of our lungs and the bottom of our hearts, three words.

Three words. Our three words. There’s no taking them away from us. They’re hardwired in to the genes by now. Splice us and Let’s Go Mets will come pouring out.

On May 30, 1962, Roger Angell took in the Mets-Dodgers Memorial Day doubleheader at the Polo Grounds, Los Angeles having pulled ahead to a 10-0 lead after three-and-a-half. Mets first baseman Gil Hodges led off the bottom of the fourth inning with a home run, cutting the home team’s deficit to 10-1.

Reaction?

Gil’s homer pulled the cork, and now there arose from all over the park a full furious, happy shout of “Let’s go, Mets! Let’s go, Mets!”

Imagine if it had been 10-2.

Let’s Go Mets has been with us forever, just about as long as there have been Mets to go. Chronicling the early days, Leonard Koppett noted that “when President Kennedy landed at Frankfurt, West Germany, and in the crowd at the airport someone held up a “’Let’s Go Mets’ sign, it was effective indeed.”

Ich bin ein Mets fan? And hopeful amid a hundred and then some losses that were already piling up like dirty dishes? Koppett called it “part exhortation and part self-derision”. Perhaps a little of each, indeed, but perhaps a little more of the first than Koppett recognized from the press box. Anybody who has sat in the depleted remnants of an already sparse crowd on the wrong end of a wide score in the closing minutes of an agonizing Flushing night will recognize this scenario, as recalled by Stanley Cohen in his 1969 tribute “A Magic Summer”.

During one game in 1963 (the team’s last season at the old Polo Grounds), with the Mets trailing by thirteen runs in the bottom of the ninth, two out and no one on base, the New Breed sent up a chant of “Let’s go, Mets.” With each new strike on the batter, the cry grew louder and more insistent. It was a battle cry that needed no battle; it betrayed neither a glimmer of hope nor the sneer of derision. It was a simple and joyous act of defiance, the declaration of a will that would not surrender to the inevitable.

The New Breed — Mets Fans 1.0, if you will — was analyzed by Robert Lipsyte in The New York Times in 1963 as a classic underdog, one who understood the brilliance of taking down the overcat in those rare instances it occurred. Alas, “the pure Metophile is likely to disappear in a few years,” Lipsyte concluded. “Even now, more and more ordinary people go to the Polo Grounds to watch a baseball game. As the Mets progress from incompetency to mediocrity, their psychological pull will be gone.”

Lipsyte didn’t see the future that clearly. Maybe the Mets who pursued garden-variety ineptitude as the team shifted to Shea didn’t inspire anthropological dissection any longer (the Times famously posted correspondents to Africa, yet operated no bureau in Queens), but Mets fans were Mets fans, and as Cohen explained in 1988, a fan base’s memory is collective and enduring.

A team’s followers always outlast its players and even its owners. They do not get sold or traded, they do not retire or become free agents, they do not sell out to conglomerates, and they rarely switch allegiance. They represent a team’s truest continuity; they are the repository of its history. And Met fans, who for years had thrived on failed hopes and comic relief, were of a very special type.

The type that may have shed some of its Upper Manhattan excesses for its trip across the Triborough, but still the type to shout and twist its abdominal muscles into knots. The type that found its voice early and its motivation often. The type that never lost its sense of irony but, when given the slightest impetus, gained a true and awesome grip on hope.

That’s what Let’s Go Mets grew into. 1969. 1986. 2006. A few other almost as great years. A whole string of not-so-great years. A mess of the mediocre kind, too. Let’s Go Mets has always been there. Let’s Go Mets is our mantra, our haftorah, our throatiest admonishment, our most sincere and personal thought.

Our hope. Our Mets.

The Happy Recap is something we all want. Let’s Go Mets is something we will keep crying no matter what kind of recap the fates bestow on us. Let’s Go Mets is for good times, Let’s Go Mets is for times less than optimal but never not good, because any time we can shout it to the skies, it means we are being Mets fans, which is all we want to be anyway. Let’s Go Mets is the eternal expression of hopefulness that fuels each and every Mets fan, none of whom would ever let the lack of a silly commodity like the likelihood of a win get in the way of who he or she is.

Let’s Go Mets is the Quintessential Mets Thing, the winner of the Metropolitan Championship and the recipient of the Joan Payson Cup, the Mayor’s Trophy and a gleaming new 1970 Dodge Challenger. Bob Murphy himself would call a victory that celebrates Mets fandom itself worthy of nothing less than a happy recap.

So if you’ll excuse the gaucheness of electronic cheerleading, I want you to get up now. I want you to get out of your chairs and go to the window. Right now. I want you to get up right now, sit up, go to your windows, open them and stick your head out and yell…

by Jason Fry on 3 April 2007 4:29 am Years ago I was in Los Angeles for work, and because of some cellphone-related mishap wound up using my room's phone for a long-distance call. For this, I was presented with a shockingly large bill upon checkout. When I expressed my surprise and indignation, the scruffy front-desk clerk smiled broadly and said, “Yeah, they get you every time, don't they?” To which I responded, now more indignant, “Who, exactly, are they? And how are you not them?”

Which brings me to John Harper's rather curious column in yesterday's Daily News. For the most part, it's a straightforward account of why Willie opted to see what Pedro Feliciano and Joe Smith had in the eighth, rather than following the expected script and summoning Aaron Heilman. Harper then talks about the Mets' swagger and asks if the '07 team will erase the Cardinals with the same indignation the '86 team did after being edged out by St. Louis in '85. A fair question, and a historically minded one to boot. I liked all that just fine. I like Harper just fine — he co-wrote the marvelous The Worst Team Money Could Buy, and I'm always happy to see his byline. But I'm baffled by the weird subjunctive woven through this column.

Like this bit, for example:

[H]ere's the difference between how the manager thinks, as compared to fans and sportswriters:

We look at the season opener, particularly this one against a Cardinals team that denied the Mets a berth in the World Series, as a tone-setter. As such, we wonder why Randolph would take such a chance on an untested reliever with a 5-1 lead and risk a meltdown that could have set the ugliest tone imaginable for 2007.

Randolph laughs at that mind-set, insists there is nothing sacred about a season opener, even in this setting, and says he has to manage with a bigger picture in mind.

Something sound strange there? How about here:

The score of this 6-1 victory won't tell just how close this opener came to turning into a referendum on Randolph's managing acumen and wiping out an otherwise sparkling effort on the part of his ballclub.

Or here:

You can argue Randolph's big-picture explanation either way, but had the Mets lost it would have been drowned out by all the screaming from fans and sportswriters.

I know exactly the kind of idiot fans Harper means — they're the ones who would have been howling on the FAN that Game 2 is the time to see what Joe Smith's made of, but not Game 1, because a veteran, battle-tested team that loses Game 1 in the late innings will be so depressed by a bad tone having been set and momentum being lost that that team will glumly shuffle into third place behind the Phillies and Braves. Or some such barber-shop bullshit. Bad move by the Mets there, Mike and/or the Mad Dog would have tut-tutted, before talking about what Joe Torre would have done.

Yes, I'm familiar with this idiocy. And had it happened that way, I'm sure I would have read words to that effect by a couple of writers who convinced me they were idiots a long time ago. But would I have read that from Harper? He clearly establishes that he can see the bigger picture — he explains it just fine several places in the column — before turning around and suggesting it would have been his unhappy duty to blind himself to that bigger picture had the Mets coughed up the lead.

Really? If the Mets had lost, would Harper have written a column he seems to understand would have been myopic? Does Harper believe — as “fans and sportswriters” supposedly do, that Game 1s are tone-setters? Would he have turned his day-after column into a referendum on managing acumen? Would he have been one of the voices screaming? If you're smart enough to know all that's silly, would you jump on the Stupid Column/Dimwit Call to the FAN Bandwagon with the slack-jawed yokels and the braying mooks anyway?

And that's what's got me confused. If the Mets had lost, what force would have prevented Harper from writing a column that started something like this:

If you're a Met fans still moaning about the bad tone set by last night's bullpen debacle, come in off the ledge. An opening-night loss hurts. A 7-6 opening-night loss to the Cardinals hurts worse. But it doesn't count any more in the standings than a loss in Game 2 or in Game 83 or in any of the 60-odd other games the Mets are guaranteed to lose even if 2007 returns them to the playoffs.

Willie Randolph understands this. While unhappy about Joe Smith's less-than-stellar debut, the Mets manager scoffed at the sky-is-falling mind-set in St. Louis last night, insisting there is nothing sacred about a season opener, even in this setting, and reminding us that he has to manage with a bigger picture in mind.

And he's right.

Was that so hard? Would someone have forced Harper to tear up that column and write something without the reason and the logic?

That hotel clerk all those years ago was an idiot, but I wasn't entirely fair to him: I doubt he had the authority to strike that obscenely expensive phone call from my bill. But I presume John Harper gets to write the column he thinks he should write. I know the kind of fans and sportswriters he lampoons, and I'm confident he's a lot smarter than they are. But that only makes me more baffled by the suggestion he'd move in lockstep with them. So how about it, John? We're going to be together for a long season — show us how you are not them.

|

|