The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 15 December 2005 10:43 am When Part I of our journey ended, we were greeted by a guide who promised to help us find what we were looking for. We now return you to floor 1979 of the Windsor Hotel to discover who resides very much alone in the Sixth Circle of Met Hell.

“Say, you wouldn’t happen to be…”

“That is right. I am Sergio Ferrer.”

It was! It was Sergio Ferrer!

“Hey, I remember you!”

“Yes, I know you do.”

“You’re the guy who me and my friend Joel…” Here I tailed off because I was about to tell him that in high school Joel Lugo and I had adopted Sergio Ferrer as the mascot, the symbol of the Mets as they stood as we ended tenth grade and began eleventh. It wasn’t complimentary.

“It’s all right. I know what you thought of me.”

“Well, I’m sorry, Mr. Ferrer…”

“Call me Sergio.”

“I’m sorry, Sergio. We were kids and the whole team seemed so absurd and futile and…”

“And I was most absurd and futile of all, no?”

“Well your batting average in 1979 was .000.”

“I walked twice. On Base Percentage wasn’t yet in vogue, but I walked twice.”

“Sergio, you batted .000 for the entire year.”

“I had some hard-hit balls. Remember the ten-run inning against the Reds?”

Did I remember the ten-run inning against the Reds? Of course I did. It was the 1979 Mets’ finest hour. It may have lasted an hour. It might have gone on forever except Sergio Ferrer made the last out.

“Ray Knight robbed me. That thing was going down the line.”

“Sergio, you batted .000 for the entire year.”

“I scored a run in that inning.”

“You were pinch-running for Ron Hodges.”

“How many runs you score for the Mets that year?”

“I’ll never forget Steve Albert’s call. ‘Even Sergio Ferrer is going to get a hit!’ But you didn’t.”

“What’s your point?”

“You were practically an object of derision to your own team’s announcer and he was a really bad announcer.”

“So?”

“Sergio, you batted .000 for the entire year.”

“It was only seven at-bats.”

“And on a team that lost 99 games you only rated seven at-bats.”

“So?”

“So what does that tell you?”

I felt bad that the conversation had gone this way. I didn’t really blame Sergio Ferrer for 1979. He was right. He was a bit player. He wasn’t why I had come all this way. If anything, I liked Sergio Ferrer then and now. What wasn’t to like? Except for the .000 batting average for an entire year.

“You know, Sergio, you’re right. You were one of the good ones.”

“That’s what I tried to tell them, but I wound up here with the rest of them. At least I tried, y’know? Elliott Maddox couldn’t wait to get out. He was all, ‘I’m really a Yankee, I made a big mistake.'”

“I know. I hated reading that after the fact!”

“And didja see how bored Willie Montañez looked that second year?”

“I did!”

“And Frank Taveras? Sure, he could run, but did he ever run after ground balls?”

“I was at a game where he struck out five times!”

“What about Mike Scott?”

I bristled at the thought. “That cheating bastard.”

“Sure, later. But do ya think he ever thought to try sandpaper when he was a rookie? He never wanted to be in New York. Even though they kept reasonably quiet about it while it was happening, almost none of them did. I don’t know why not. It’s not like there was any pressure. Did you know that we didn’t even draw 800 that entire year?”

This seemed to be a big bone of contention on 1979, that the paid attendance at Shea Stadium was all of 788,905. The largest market in the country, the proud National League tradition and fewer than 800,000 people bought tickets.

“I was four of those 788,905,” I told him as if to regain his trust.

“I know you were.”

“And if I had been older, I probably would’ve been more.”

“I know you would’ve been. You and I may have our differences on what I did then…”

“Sergio, you batted .000 for the entire year.”

“…but I know your heart is true. Not that will do you much good here, eh?”

With that, we arrived at end of the hall, to what Sergio Ferrer said was my destination. No more false starts or dead ends. I was in the deepest, darkest corner of 1979. Time to confront my Demon.

The number on the door read 3. Sergio knocked on it and called inside. “Hey, Digger, man! You got company!” He turned to me and wished me good luck. I was gonna need it. With that, Sergio disappeared from view. He was still batting .000 for 1979, but he was OK in my book.

It was a different story regarding the figure who opened Door No. 3.

“Yeah?”

“Hi.”

“Hi.”

This was awkward. The man inside didn’t look too happy to see me. He didn’t look too happy in general. But he wasn’t shooing me away or anything. Looked like he had nowhere else to go.

“Uh, mind if I come in?”

“Suit yourself. I’ve got nothing but time.”

I entered his room. The very first installment of SportsCenter, from September 7, 1979, was on the television. No sound. “TV works,” said the room’s occupant. “But the clicker is broken.”

Too bad the sound wasn’t on. There was a long, awkward silence as we watched a continuous loop of Pirate and Phillie highlights. I’d once heard the original SportsCenter actually showed no highlights but the Windsor apparently had its own feed.

“Lucky bastards,” my host grumbled.

“How’s that?”

“Pittsburgh. Philadelphia. Look at ’em. They’re contenders.”

“What do you care about them?” I was irritated by the tone in his voice and my irritation gave way to emboldenment. “You’re a Met.”

“Don’t remind me.”

At last we got to the heart of the matter. This is why I journeyed all the way to this particular hotel in this particular Circle of Hell — the Sixth — and this particular floor — 1979.

“I wish you wouldn’t talk that way.”

“What’s it to ya?”

“I’m a Mets fan.”

“So?”

“That doesn’t mean anything to you?”

“Should it?”

The nerve of this guy. He grabbed a bat and started swinging as if in the on-deck circle. I thought it was a bat. It was actually a spade, the kind a gravedigger might use.

“Listen, no offense…”

“No offense. Coming from you, what else is new?”

“Hey, that’s a low blow. I led the team in RBIs.”

“You were tied.”

“Nobody had more.”

“You had a lousy 79.”

“Who was I supposed to drive in? Ferrer?”

“Flynn had 61 and he was batting eighth.”

“Whaddaya want from me?”

Yes, what did I want from him? What did I want from the man who stood before me so disillusioned, so down, so damned? He looked so much more comfortable with the shovel than I remembered him being with a bat.

“I want you to apologize.”

“To who?”

“To us. To me.”

“To you? For what? Look, you may not like that there weren’t many men on base for me or that I tailed off dramatically in the second half or that I practically invented The Wave by the way I merely motioned toward hard grounders to either side of me as they traveled to the outfield or that I lost my temper one day when you were there and gave the crowd my special salute…”

“You know, you’re not making a case for yourself here.”

“What I’m getting at is it wasn’t my fault.”

I was incredulous. It was one thing to suck. Sucking was rampant up and down this hallway. Supporting those who sucked became a badge of honor for me and for Joel and for however many of the 788,905 who never gave up more than a quarter-century ago. Well, we gave up but we never gave out. We remained Mets fans no matter how bad things got, through all 99 losses, despite finishing 35 out of first and 17 out of fifth and no matter how dumb and dopey the vast majority of our peers accused us of being.

It was one thing to suck. It was another thing to not own up.

“How can you say that?”

“Well, it wasn’t.”

“You say you have lots of time on your hands here. Explain.”

“First off, we sucked.”

“We’ve established that.”

“Everybody and everything sucked. That fucking mule. The time our game was called for fog. The time somebody called time to go to the bathroom and the game had to be picked up the next day. The way nobody came. The way they couldn’t even have Orosco’s uniform ready for Opening Day. Those crazy ladies. Did you know they wanted to reuse the balls from BP in the games?”

“Do you really think I’d come all the way here if I hadn’t read Jack Lang’s book?”

“It was so goddamn depressing. There was no talent. Haven’t you looked around here?”

Geez, what did he think I’d been doing since I got the Windsor. Joe Torre’s running around the lobby trying to fix everything but he has no clue. Ed Kranepool’s been here too long and Jesse Orosco got here too soon. Mike Scott and Neil Allen and Kelvin Chapman, too. There’s nobody in 41, which is where the problem started. Next door I find all the ex-Reds: Zachry, Flynn, Henderson, Norman, Youngblood. They were lost souls before they ever checked in. Falcone? Never could concentrate. Stearns? Always was chippy. Swannie? Always had a hunch he was more a rolfer than a pitcher, not that he was a terrible pitcher. Mazzilli? He wasn’t Tony Oliva and he wasn’t Tony Manero. Everybody else? It’s like George Washington told the Continental Congress: I begin to notice many of us are lads under 15 and old men, none of whom could truly be called soldiers.

“Yeah, I’ve looked around.”

“So why you picking on me?”

“Because…”

“What? Say it. SAY IT!”

“BECAUSE YOU, RICHIE FUCKING HEBNER, SAID YOU DIDN’T WANT TO BE A MET, NEVER EVEN PRETENDED YOU WERE HAPPY TO BE A MET AND COULDN’T WAIT TO STOP BEING A MET!”

I felt better.

“That’s it? That’s what you’re so pissed off about for more than 25 years? That’s the rock you’ve been carrying on your shoulder since 1979?”

“Yes.”

“You think I was the only one?”

“No.”

“Fuckin’ A right ‘No.’ You found out that Elliott Maddox regretted being a Met, that Mike Scott was never comfortable in New York that Frank Taveras was marking time.”

“Yes, I found that out.”

“So I ask you again, why do you have in for me, Richie Hebner?”

“Because you were the only one who was so fucking obvious about it back when it was going on.”

“Don’t I get credit for honesty? I said I didn’t want to be traded here.”

“You’re not supposed to say stuff like that! Not when I’m 16 years old and still believe the Mets are full of Mets who like being Mets.”

“Look kid…” — suddenly I was ‘kid’ to him — “…sorry to bust your bubble, but that’s life. I grew up in the family funeral business, so I know something about how there are no happy endings. Why waste a lot of breath on happy talk when we’re all gonna die?”

OK, this was getting morbid.

“Jesus, Hebner, will you listen to yourself? Baseball is the annual rite of renewal and spring and all that and you’re sitting here totally plunging me into the morass?”

“Well, how do ya think I felt? I’d been a Pirate for eight full seasons and we won five division championships. Then I signed with the Phillies and we won two more division championships. I was the starting third baseman on the team that won the 1971 World Series. I played with Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell and then with Mike Schmidt and Steve Carlton. I was on some of the best teams of my time. I was a winner! And then on March 27, 1979, with like a week to go before Opening Day, I’m traded to the last place New York Mets. Their best player was Chico Escuela. Spring training was almost over! So don’t tell me about how great spring is.”

For a second, he had me going. Everything he said was true. His number had actually been retired by Pittsburgh. Technically, it was retired for Pie Traynor but they took forever to do it so Hebner got to wear it. I had always looked at him as a good player when he was with the Pirates and the Phillies. I was excited when we got him for Nino Espiñosa. I was overjoyed to watch him on Opening Day 1979 when he got four hits and four RBIs and the Mets won for what seemed like the last time all year. I told him this.

“I always looked at you as a good player when you were with the Pirates and the Phillies. I was excited when we got you for Nino Espiñosa. I was overjoyed to watch you on Opening Day 1979 when you got four hits and four RBIs and the Mets won for what seemed like the last time all year. I’m telling you this.”

“So you see what I’m saying.”

“I absolutely do not.”

“What part?”

“All of it. It’s bullshit!”

“What do you mean?”

“If you were a good player, you’d go to the team you were traded to and say, ‘all right, how can I make my new team better?’ Instead, you were like every dick in every gym class who looked pained that the gym teacher assigned him to a team with the likes of me. You don’t whine and sulk and pout and let every fan know right away that you hate being where you are.”

“Well I did hate being where I was.”

“Do you hate being where you are, too? At the Windsor? In the Sixth Circle of Met Hell? Forever trapped on 1979 and in 1979? Do you hate knowing that as far as Faith and Fear in Flushing is concerned, you were never traded for Phil Mankowski and Jerry Morales, two non-prizes to put it mildly but at least they weren’t you? Do you hate knowing that even though I have a baseball card saying you became hitting coach of the Durham Bulls that in fact you will forever be the crappy third baseman on the crappy 1979 Mets and that you can sit in this crappy hotel room with your Pirate and Phillie highlights watching those teams go on and win without you while you finger your gravedigging shovel and stew in your own resentment? Do you hate all that?”

“Yes. Yes, I do.”

“Well too fucking bad!”

I walked out and slammed the door behind me. Man, that felt good! I opened the fire exit and it led me right out onto the street. I hailed a cab and asked the driver to take me to Dorval Airport. I was out of Met Hell. Nothing was gonna stop me now. Got my boarding pass, sailed by customs, got on my flight to LaGuardia. Found my row. I was given a middle seat, but the flight was fairly empty, so I wasn’t too worried. They got through reading the emergency instructions and I figured I was home free.

Not so fast. Two large men appeared and told me that they had the respective window and aisle seats. They looked pretty much alike to me. Both pretty big, both kind of obnoxious. One was a few years older and probably a few pounds heavier than the other. They each alternated dopey grins with suspicious grimaces. They literally rubbed me the wrong the way. I hate the middle seat. But I was happy to have emerged from the Sixth Circle of Met Hell, so I tried to make the best of it.

“So,” I asked, “you fellas looking forward to getting to New York?”

“Oh no, this flight isn’t going to New York,” said the window passenger. I gulped.

“He’s right,” the aisle passenger said to me. I breathed hard.

“Uh, where are we headed?”

They both laughed Devilishly and answered in unison.

“This,” they informed me, “is the flight to the Seventh Circle of Met Hell.”

Oh no.

by Greg Prince on 13 December 2005 10:35 pm The Sixth Circle of Met Hell is still being wrangled. You'd think with temperatures in the 20s that it would be fun to warm up there, but it's a job.

In the meantime, we get letters, this one from reader Joel Fradin. He knows who he wants to play second for Los Metropolitanatos en el Nuevo Año. It's not Japan's greatest shortstop, it's not the 1-for-18 guy and it's not the man whom a dear friend who used to post here refers to as Mark Unpronounceable.

Joel Fradin, tell 'em who you want:

I suspect the Mets hierarchy is influenced by blogs like yours. Do me a favor: please publicize the fact that Kepp has hit everywhere he has been, including 30 games in the bigs. He's a younger Grudz and deserves a full shot. Please help.

Not exactly a long-distance dedication, but there ya go, Joel. If Omar Minaya is the least bit influenced by the Faith and Fear Faithful's call for Jeff Keppinger, I'll be a Mookie's uncle. But thanks for your confidence in our pull.

For our next trick, we'll roll back box seat prices to 1977 levels and revive Banner Day. Of course my banner will require like twelve bedsheets.

Back to Hell…

I go marginally soft on Bernie Williams at Gotham Baseball. I think it's out of releaser's remorse where Mike is concerned.

by Greg Prince on 9 December 2005 6:01 pm The New York Mets today signed 47-year-old Julio Franco to a senior league contract. He will report to their Frostproof, Fla. affiliate in time for the early-bird special.

OK, got that out of my system. Y'know what else is out of my system?

Cairo, DeFelice, Graves, Mientkiewicz, Offerman, Heredia, Takatsu and — this should send everybody dancing into the snow barefoot — Gerald Williams. Looper, too. (Not so sanguine about the disappearing of Robero Hernandez, but you can't have every old thing.)

We talked about dead roster spots in the second half of last season. Episodes of deadwood, really. Julio Franco's older than them all…combined. And that's not counting his real age, whatever it is (it probably ain't 47). He calls Jose Valentin “kid”. He calls Jose Reyes “as yet unborn”. Remember that charming story about how Lou Brock mistook Tom Seaver for the clubhouse boy at the 1967 All-Star Game and Seaver, awed, brought him a soda?

Big deal. Julio Franco does that sort of thing every day. Leo Mazzone spent the last five years leaving Geritol by his locker and waiting for tips.

YES, he's old. And YES, that's the stuff of about a jillion obvious jokes for us slightly younger middle-aged unathletic sorts. I'm not going to crack any more of them until further notice because last I checked, that old bastard could hit. It probably helped he was wearing an Atlanta uniform, but he's doin' somethin' right. (“Doin' somethin'” is the necessary construction here because the practice of spellin' words so they'd end in “ing” hadn't been invented when Julio was comin' up.)

As for Jose Valentin, I'll tell you what I know about him:

1) He put up great power numbers before injuries curtailed him.

2) That's the sort of thing we acquired Mo Vaughn based on EXCEPT Jose Valentin isn't penciled in as our cleanup hitter.

3) He's not John Valentin, a mistake I commonly made before John Valentin summered here in 2002.

4) I once sat in a hotel room in the vicinity of O'Hare, breathing in fumes and straining to pull in a staticky Mets-Brewers game from Milwaukee and heard Bob Uecker continually refer to the Mets manager as Bobby Valentin.

If I haven't mentioned it before, I'm psyched for Tike Redman. This is based completely on two performances against us, Bob Murphy Night when he got three hits and Murphy's Law Night last July in Pittsburgh. What could go wrong did go wrong, though Tike was as responsible as ex-Met Braden Looper for that. If he doesn't produce for us as he did against us, it will take me months to acknowledge it. “Don't you remember what he did to us? He's GREAT!”

Of course he may literally not do a damn thing for us. A year ago we were probably cooking up snarky lines on our own about Kerry Robinson, Ron Calloway, Luis Garcia and The Old Cat Andres Galarraga. They wound up not helping us but they didn't hurt us a bit.

It's December. We've got Julio Franco. I hear the cold works wonders at preserving old treasures.

by Greg Prince on 8 December 2005 7:16 am

One has, for at long last certain, left the building. The other has said goodbye to the game. The cold December night yields fresh miss.

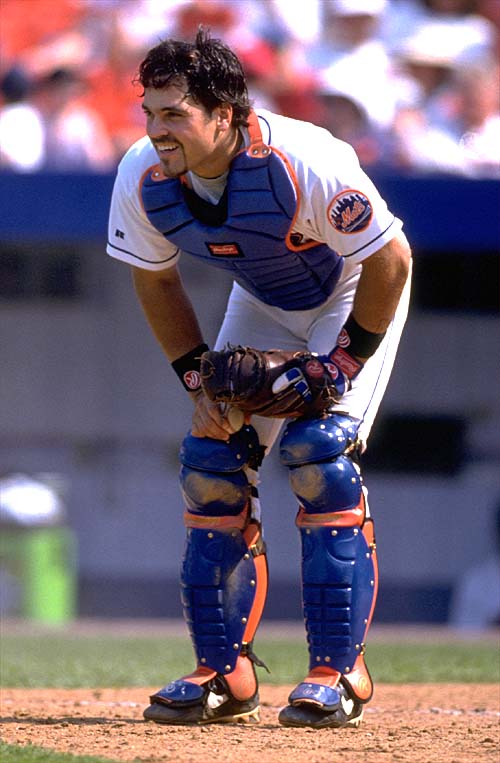

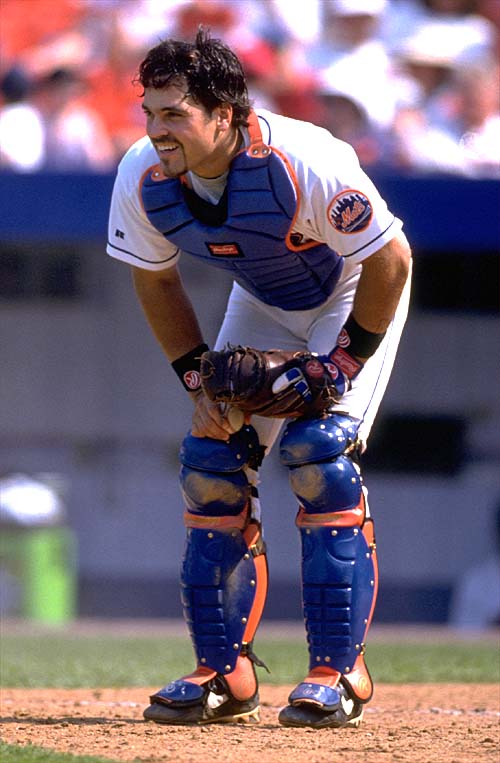

The Mets did not offer Mike Piazza arbitration. We were all but certain they wouldn’t and they didn’t. Now we know that the provisional farewell of October 2 was really it. What seemed like reasonable fait accompli that Sunday seems unnecessarily cruel two months later. The next time the name Mike Piazza flashes on a screen, it will be the name of an ex-Met. The next professional game in which Mike Piazza swings or even crouches, he will appear to us as odd as Tom Seaver did in Red, as Keith Hernandez did in Wahoo, as every Met does when not a Met. Mike Piazza is a Met. Always will be.

John Olerud should be no more than a footnote to us by now. Technically, he hasn’t been a Met since the last century, since Kenny Rogers threw one too many fourth balls. But he never stopped being ours. Blue Jay fans and Mariner fans may beg to differ and I wouldn’t stop them. Phillie fans thought Tug McGraw was one of theirs, too. The wondrous ones you can afford to share.

Oly doesn’t need a helmet anymore. Mike apparently still does. Somewhere tonight, it’s 1999.

by Greg Prince on 7 December 2005 6:50 pm Six years to the day that it was learned he was leaving the Mets to sign a week later with the Seattle Mariners, John Olerud has announced his retirement from baseball.

Baseball is diminished.

Baseball fans are diminished.

The Mets, long detached from him, are diminished.

We are all diminished.

John Olerud played all of three seasons for the New York Mets and yet ranks, according to Faith and Fear in Flushing, as the No. 20 Greatest Met of the First Forty Years. We reprint here what it says on his virtual plaque.

Catch the breeze and the winter chills in colors on the snowy linen land.

On December 20, 1996, the Mets traded Robert Person to the Toronto Blue Jays for John Olerud, allegedly on the downside of his career, supposedly too fragile of psyche for New York.

Look out on a summer’s day with eyes that know the darkness in my soul.

In three seasons that didn’t last nearly long enough, Oly batted .315, including the eternally untoppable .354 of 1998.

While almost every other Met froze down that pitiful stretch, John sizzled. Fourteen plate appearances, fourteen straight trips to first or beyond.

Spent virtually all of the late ’90s on base.

Caught everything everybody threw him or hit toward him. Started a triple play against the Giants in ’98 — got two assists and a putout.

Entered the final week of 1997 with 88 RBIs and finished with 102.

Hit for the cycle against Montreal earlier that September, a cycle that, like every other cycle, required a triple. It was the only triple he hit that entire season because John Olerud ran with two packs of freshly chewed Bazooka stuck to the bottom of each spike.

Weathered faces lined in pain are soothed beneath the artist’s loving hand.

His one Mets post-season went like this:

• .349

• First homer by a lefty off of Randy Johnson in two years

• Deep fly that Tony Womack couldn’t catch

• Homer off Smoltz

Then, when no hope was left in sight on that starry, starry night…

• The perfectly placed bouncer between Ozzie Guillen and Bret Boone to win Game Four

• Homer off Greg Maddux to start Game Five, providing the entirety of the Mets’ offense for fourteen innings.

Colors changing hue, morning fields of amber grain.

In a game that is all but forgotten because both the protagonists and the antagonist went on to do so many more interesting things, John Olerud lifted the 1999 Mets to perhaps the most thrilling May victory in franchise history, driving home the tying and winning runs off a stubborn, faltering, previously infallible Curt Schilling in the ninth at Shea.

It was a sign of good things to come.

Swirling clouds in violet haze reflect in Vincent’s eyes of China blue.

Unlike, say, Kevin McReynolds, Olerud’s quietude actually enhanced his personality. His muteness along with his omnipresent hard hat were shown off as signatures in those hilarious Nike Subway Series stickball commercials. The other players swore by him.

Flaming flowers that brightly blaze.

Cataloguing all the good baseball John Olerud committed in three short seasons should have been enough to earn him at least five more as a Met.

They would not listen, they’re not list’ning still, perhaps they never will.

Instead, Steve Phillips turned his back on him. John didn’t go on the open market, though. He and his wife headed home for Seattle, where his parents and in-laws could regularly babysit the Oleruds’ infant son.

I could’ve told you, Oly. This team was never meant for one as beautiful as you.

by Greg Prince on 6 December 2005 8:34 am All heck has broken loose. The Fifth Circle of Met Hell is populated by men who had to really strive to land on the dark side. Jefferies, Kingman and Benitez accomplished varying degrees of good as New York Mets. Yet here they are in the part of MH just shy of where the MFs can be found.

Anybody else? Anybody we want to cast down, down, down into the burning ring of fire before we descend into the serious heat of Circles 6 through 9? 'Cause once we get there, there's no turning back. Those dudes are so out and out evil that each one of them gets a sphere unto his own bad self.

I can think of a few guys who deserve dishonorable mention, fellas who weren't altogether demonic but just the same shouldn't be let off with just a warning. There needs to be at least a little charbroiling around the edges of their cards, enough to keep them honest.

Five more for the first five Circles. Put 'em anywhere you want. I'm not particular. I am, however, peevish.

Brett Butler — He is the Demon of Logical Expectations Dashed. Brett Butler was every thinking fan's answer to the perennial black hole at the top of the order. He was the guy who punished us mightily as a Dodger in the early '90s, it seemed, because we didn't sign him when he was available after 1990. (Instead we signed another speedy outfielder, but let's not get ahead of our Hell.) When 1995 dawned late and Brett, 37, was still on the market, this was a chance to make good. We grabbed him. Brett was a Met. At last, he would bunt and steal and run down fly balls for us instead of against us. He would reverse the history that he could've positively affected in the first place. Brett Butler would be the greatest prototypical leadoff hitter the Mets had ever had. Yeah, that was the idea. Instead, Brett Butler never got untracked in New York. In fact, he rather sucked. Couldn't field worth a lick. Batted .311, which sounds good until you realize 1) he batted .344 against us as a Dodger from 1991 through 1994; 2) his average languished at .256 as late as July 16; 3) he put on this push, I'm now convinced, to get himself traded back on August 18 to his beloved old team and reunite with baseball's windiest bag Tommy Lasorda and harass some poor kid who played in replacement games in the spring and, upon hanging 'em up, criticize Mike Piazza as a “me player” or some such defamation of character. Whatever residual sympathy a human being would feel for Butler after it was revealed he had battled lip cancer shriveled when that human being received a form letter from a speakers' bureau extending an invitation to have Brett Butler speak to your company about what a great, pious guy Brett Butler is. His inspirational tale can be shared with your employees for a mere $20,000. I thought it was called “giving” testimony. Whatever real or imagined sins I've projected onto Brett Butler pale next to my irritation that I thought it was a really good idea that we sign him and it wasn't.

Pete Harnisch — Another one who was going to transform the 1995 Mets. He did no such thing. A total bust in '95 (2-8) and '96 (8-12). Gave up Tom Prince's only home run of 1995 at Shea while I watched. In later years, I'd get a kick out of Tom Prince's successes, Prince displays of athletic acumen being a rare phenomenon. I didn't that night. Somehow Harnisch rated the Opening Day start in '97 and was shelled. Then the fun started. He was overcome by tobacco. He was steamrolled by depression (as one who has been treated for panic attacks, I claim immunity to charges of insensitivity). He was blaming it all on Bobby Valentine who, granted, was unloved by any dozen players but was also busy lifting the Mets to their first winning record in seven years. By the time Harnisch crawled back to the rotation, he had nothing left except venom for Valentine. One said the other spoke with a forked tongue. I think it was Harnisch on Valentine. Bernard Gilkey presented the manager with a plastic fork as a show of team solidarity. Ya had to be there. Either way, the native Long Islander and Yankee fan (to paraphrase Joliet Jake Blues, I hate Long Island Yankee fans), was gone, good riddance. Natch he put up two very good seasons for Cincy thereafter. Some guys just piss you off by their very presence. That was Harnisch. He probably doesn't like me either.

Doug Sisk — No, not for why you think. Not because all at once a dependable setup man went south. I felt bad for Doug Sisk when he became the target of targets at Shea during the good times of the mid-'80s. Honestly, people, we're watching a team for the ages here and you're going nuts because Doug Sisk has fallen on hard times. Have some sympathy for a pitcher who rolled us to the cusp of the promised land in '84. What's the point of booing him? (I'd repeat that line ten or eleven-thousand more times from then until now.) By '86, he was kind of not altogether terrible, I don't think. When he lurked in the pen ready to start the eleventh inning of Game Six should it have come to that, I wasn't completely ready to kill myself. It never came to that and he was still around in '87. The first game I ever took Stephanie to, on May 15, 1987, featured Doug Sisk. The Mets had a big lead. Homers galore. El Sid was pitching a no-no through five. It was a festive night. But Sid had to leave with one of those nagging Sid injuries. In with nothing but emergency tosses and a big surplus on the scoreboard came Doug Sisk. The Giants immediately touched him up. Everybody except possibly me and my new girlfriend were booing (and maybe Steph joined in so as not to feel left out). Aw, c'mon! We're the defending world champions and we're winning and he's not blowing it for us. Lay off! No, I never held any animus for Doug Sisk when he was a failing Met. So why Hell? Because after he was mercifully traded by the Mets to Baltimore after '87, he said (and I'm paraphrasing) that he had no intention of ever wearing his 1986 World Series ring again. Instead, he'd wear the one he'd win with the Orioles. Let the record show that the Baltimore Orioles, with Doug Sisk a pillar of their relief corps, opened 1988 with 21 consecutive losses. Say something that fucking stupid and you deserve to rot in Hell, you worthless ingrate.

Rich Rodriguez — This exercise needs a situational lefty. They can't all be let off as bit players in the larger melodrama. Of all the sad southpaws too numerous to mention, I condemn ye Rich Rodriguez to the fires down below. I choose you because on the sopping cold afternoon of May 20, 2000, I waited out a three-hour rain delay (three hours!) with Joe to witness the Mets take on the Diamondbacks. That's three hours with Joe and no baseball. There was no guarantee that the thing would ever start and I wasn't in much of a mood to find out if it ever would. “Why are we even staying?” I asked. “Because,” Joe said, “this might be the day the Mets get their first no-hitter.” God damn it! Why did he have to say that? Well, the weather cleared and the game got underway and Mike Hampton didn't throw a no-hitter, but the Mets got themselves eight runs and things were going swimmingly if slowly. Come the eighth inning, I'm tired and looking at train schedules. Sure, like every other fan who likes to trumpet his moral superiority, I generally don't leave games early (and I give every foul ball I catch to strange kids; yeah, right), but I'd had a good six hours in the company of Joe (great guy, let's leave it at that) and soggy Shea and the thing wasn't in doubt. If I missed this opportunity to bolt, I wouldn't get home to my wife, who'd been waiting for me as long as Sisk had been waiting for his Baltimore jewelry, until like midnight three weeks from Thursday. When the eighth was over, I gathered my stuff and informed Joe that this was it, I'm leaving, I promised Stephanie I'd return before Flag Day, game's in the bag, OK? Joe, who in a game situation (which is to say at any moment from first pitch to last), rarely exchanges glances with anything but the field and his scorebook, didn't look at me. He just told me that it was fine with him, but if the Mets blow this 8-2 lead, that it's on my head. Ha ha, I said. And as I turned to leave, mop-up reliever Rich Rodriguez surrendered a single to erstwhile forking Met Bernard Gilkey. As I exited the stadium, Travis Lee doubled. As I swiped my Metrocard, Danny Klaasen walked. As I looked left for the 7 from Flushing, Tony Womack singled. As I boarded, Damian Miller singled. Fuck! Rich Rodriguez is giving this thing away, I'm at 111th Street and it's on my head and what's worse, Joe's never, ever going to let me forget it. It took Franco and then Benitez to right things, and if those are your heroes, you know who your villain is. The final score as the LIRR train I needed pulled into Woodside was Mets 8 Diamondbacks 7 Rich Rodriguez Screw You. Never mind that we won. Joe has never, ever let me forget it. It's on my head. Later in 2000, when the Mets graciously sent all their non-roster scrubs out to the foul line to take part in the introductions prior to Game Three of the NLDS, only one demi-Met was booed to within an inch of his life. And only one Met has ever been booed by me during the postseason. Let it be on your head, Rich.

Mike Bacsik — In 1992, Eric Hillman came to the Mets and bolstered their rotation shortly after their pennant race hopes crumbled. Still, it was a nice shot in the arm, a rookie tossing two gems in his first two starts. The second win, in San Francisco, earned him an interview with Gary Cohen the next day on the pregame show. I guess Gary felt there hadn't been enough Hillman revealed because he asked something along the lines of “is there anything you'd like to do differently next time out?” as his last question. Big Eric (he was 6' 10″) responded, “I'd like to see that George Bush is re-elected.” With that, the interview was over and I could never root for Eric Hillman again (not that there'd be much opportunity). If there's one thing I don't need to know, it's where ballplayers, particularly Met ballplayers, stand politically. OK, I admit it: Eric Hillman and I had divergent views on who would make a better president. I suppose if he started singing the praises of Governor Bill Clinton that I would've been predisposed in his favor, maybe. But maybe not. Ballplayers are private citizens and have every right to express their views, but don't drag that shit in here, y'know what I mean? (Which is kind of what I seem to be doing at the moment, I reckon, but we are talking Hell, so decorum is bound to get singed.) And if you do, at least don't suck. A preponderance of Major Leaguers with an opinion on such matters, I've learned over the years, vote differently from how I do. Doesn't bother me. Mike Piazza actually compared Rush Limbaugh to George Washington last season and it didn't stop me from loving Mike, no matter how deranged that comment was. Zeile and Trachsel and Leiter (especially) all swing to the right and I didn't think twice about cheering for them as Mets. It's the Hillmans that good sense (if not logic) tells me should shut the eff up about such things, at least for the record. So it was in spring training of 2003 that the New York Post — no really, the Post — did a story on how supportive the Mets were of the war in Iraq. Two players leap to mind as having been quoted: David Weathers and Mike Bacsik. I don't remember exactly what Weathers said, but I distinctly recall Bacsik, with all of 14 big league games to his credit, lit out after the bleeping liberals who were ruining this country by not getting in line behind our president, et al. That was it for me and Mike Bacsik. The 10.19 ERA he compiled, even while wearing the uniform of my team, filled me with joy throughout all five appearances he made prior to his disappearance from the active roster (imagine not being good enough to pitch for the 2003 Mets). You want to tell me I'm a bad American? Don't be such a crummy National Leaguer while you're doing so.

Anyway, those are my Hellish leftovers. Yet they're practically Princes (and I don't mean Tom) compared to who we're gonna meet next. It will be my privilege to take it down a notch to the Sixth Circle. You're not gonna like who's waiting for us. He could bring about world peace and universal health care and I know I wouldn't like him.

Omar Minaya is talking to everybody at the Winter Meetings, and I mean everybody. Find out who has a spirited proposal that's very much to his liking at Gotham Baseball.

by Jason Fry on 5 December 2005 8:08 am No, this isn't a freakout over Gaby Hernandez plus Somebody Else for Paul LoDuca — for equal servings of brains and brouhaha about that, check out the reader comments on the always-excellent MetsBlog and MetsGeek. (Better bring your oven mitts.) My 30-second take: We have to wait until March, since you gotta see the team that goes north before you can say the GM's gone south. Though the Gaby/LoDuca trade is an ideal sadistic social experiment designed to keep the Moneyball and Makeup gangs clawing at each other's jugulars. LoDuca's old, doesn't walk, doesn't hit for power and is overpaid — unless he's battle-tested, doesn't strike out, a high-average hitter and a clubhouse leader.

(And of course if he's a Diamondback by the end of the week, we won't give a fig about his qualities.)

Nope, that title up there refers not to whether or not our GM has lost his mind, but to the resumption of our trip through Met Hell. It's a tour that was put on hiatus because, honestly, what's the point of fuming about the sins of Rey Sanchez while Carlos Delgado and Billy Wagner are at the podium? But now that they've been introduced, time to delve a little deeper. Welcome to the Fifth Circle of Met Hell, reserved for three men we may not actually hate, but sure did come to dislike. (If you want a refresher, Circles One, Two, Three and Four are still open for tours.)

Dave Kingman — As a teenager I lived in St. Petersburg, Fla., and in 1985 you couldn't go to a Mets (or Cardinals) game at Al Lang without eventually hearing about the home run Dave Kingman hit there as a new Met in 1975 — the older fans would point beyond the left-field wall to Bayshore Drive, noting that the ball landed right there and one hop took it into Tampa Bay. That would inevitably lead to a discussion of the enormous blast Kingman hit in Ft. Lauderdale off Catfish Hunter. So far so good. Except the conversation would soon run aground on the unhappy reality that Dave Kingman was a psychopath. What got into him? It can't have helped that the Giants tried their hardest to ruin him, shuffling him madly from first to left to right to third and, as if that weren't punishment enough, ordering him to the mound for mop-up work. The Mets were a fresh start and Kingman seemed pleasant enough at first, but the sheer oddity of the man became increasingly hard to hide: He grumbled about official scorers, threatened to do nothing but bunt when Yogi Berra sensibly tried platooning him, and seemed to glory in remaking himself into an utterly one-dimensional player, interested in nothing except hitting astonishing home runs and increasingly incapable of doing anything else. As for fan relations, read Jeff Pearlman's The Bad Guys Won, in which Sky King takes sadistic delight in ruining young Pearlman's prized baseball. In Chicago Kingman blew off his own T-shirt Day; in Oakland he pursued a crazy/scary jihad against Sacramento Bee sportswriter Sue Fornoff, haranguing her for daring to enter the locker room to do her job, refusing to discuss career milestones while she was present, and finally sending her a live rat in a gift box. That touching gift was delivered in June 1986, and 1986 would prove to be Kingman's last season. No team was interested in his services in 1987, despite the fact that he was just 38 and was coming off a 35-HR campaign. Was it the immense train of baggage that Kingman dragged along with him? Ask Sue Fornoff. Or Mets fans.

Gregg Jefferies — This one hurts, because Gregg Jefferies was my favorite player when I was 20. “You only like Jefferies because he's the Met most like you,” the Human Fight said that spring, and he was dead-on as usual. I liked the fact that Jefferies was prodigiously talented, prodigiously arrogant, awfully young, and the property of the New York Mets, because I liked to think that was also a pretty good description of me. (I can only pray I managed to track down and burn every copy of a fantastically horrid poem I wrote along those lines, a memory I had successfully repressed until a couple of minutes ago. God, I hate myself.) Anyway, Jefferies had lit up the TV down the stretch in 1988, playing his guts out (and, OK, somehow getting hit by a batted ball) against the Dodgers, and while that turned out wretchedly, it seemed certain that he and we were headed for great things in 1989. Except we weren't; in fact, by about the midpoint of 1990 we all knew Jefferies was socially maladroit to an avert-your-eyes degree. I remember reading the famous Sports Illustrated article about him with increasing horror, from his inability to stop shocking minor-league crowds with his incessant swearing to the portrait of him as one of these pitiable marionette children wrecked by a stage-managing parent. Yes, he was treated cruelly in the clubhouse, coddled by Davey Johnson and used poorly by Buddy Harrelson, but he also seemed to have a gift for saying the wrong thing, doing the wrong thing or just being the wrong thing. Then there was the infamous “open letter” on WFAN — I cringed the moment I heard “Jefferies” and “letter.” (And then cringed again when Ron Darling, who should have known better, compounded the idiocy with his own open letter.) The phenom was done before his 33rd birthday; he's 38 now, and for his sake I pray he's not in the swimming pool perfecting his swing with his crazy father.

Armando Benitez — Originally Armando had no place in Met Hell; according to the ground rules, he seemed safe. After all, it wasn't lack of trying that undid him in all those big games; if anything, it might have been trying too hard. God knows we've argued about this before — check out the run of comments appended to this post for a lively discussion. But on further review he's here, and not just because at least once every winter until I die I'll realize I've just spent the better part of an hour working myself into a fury thinking about how Armando walked Paul Fucking O'Neill. No, Armando makes the list because I think the final judgment on his failures and frustrations will be that too many of them had something to do with his utter inability to control his emotions, to focus, and to lead a life that wasn't a train wreck on the field and off of it. It wasn't bad luck that made Armando's mechanics fall apart time and time again when he'd come out of the bullpen and find his heart starting to race. It wasn't bad luck that made him abandon the splitter after a couple of tries and start trying to throw 200-MPH fastballs. And then there was the constant parade of stupidity surrounding his man-child act — the domestic violence, the freakouts at the press, the screaming that he needed an empty locker next to his. (And that's just the stuff we knew about — Bob Klapisch had a story in the spring about Armando coming to Shea the day of the Todd Pratt game and saying he wouldn't pitch because he was distraught over a fight with his girlfriend. God only knows how many other things like that happened.) With Armando it was always Some Damn Thing, which would be followed by some horrid meltdown, which would be followed by an orgy of coddling and madly supportive testimonials in the papers and desperate attaboying until Armando's rickety confidence was taped back together, at which point Some Other Damn Thing would happen. That's not to say every blown save began inside Armando's skull, but it's impossible to look at Ozzie Guillen and Craig Counsell and Brian Jordan and J.T. Snow and Jorge Posada and Pat Burrell and Paul Fucking O'Neill and every other cigarette burn to the ulcer that was Armando Benitez, Closer, and chalk them all up to bad luck. Armando wasn't a bad closer or a bad guy, but he's most definitely on the list.

Next stop: That's it for Mets Heck; from now on we're sizzling. The sixth through ninth circles of Met Hell are home to truly detestable occupants. Bring the hate. You're gonna need it.

by Greg Prince on 5 December 2005 1:21 am The News is reporting the Mets traded Gaby Hernandez and another minor leaguer yet unnamed for Paul LoDuca.

So what else is new? Another prospect who may or not haunt us for a proven commodity who's getting long in the tooth. I had the feeling we weren't getting either of the two catchers who had offers outstanding. That was weird to begin with. LoDuca's always seemed like a real character guy. He also seems like he may be following the Mientkiewicz career trajectory. But I tend to go with guys I've heard of who've done good things not too long ago, so yea for us for now.

A little historical perspective, as if you couldn't come up with it yourself, is at Gotham Baseball.

by Greg Prince on 1 December 2005 1:53 am In the wake of the Mets trading for Carlos Delgado and signing Billy Wagner (let's dwell on that sentence fragment before moving on…ahhh…), I've heard the Mets referred to as a team built to win now. Where I'm from, winning now beats winning later.

Now is sooner. One's sense of what will happen sooner is generally more accurate than one's sense of what will happen thereafter. The sooner something happens, the more gratifying something is, or at least it means we are more quickly assured of the resulting gratification if indeed gratification results. Get me close to winning in 2006 and I don't have to wait for a year to be named later.

But to my continuing amazement, I've learned some people, both those on our side and those who viciously rub their hands together as they await our demise and destruction, think “win now” is Stern stuff, that they are two of the Seven Dirty Words and that they require the washing out of the mouth with high-quality, natural, handmade Manor Hall Soap.

“The Mets are a 'win now' team,” the voices gravely intone as if it's very, very bad news, as if ambition can only beget failure, particularly in this part of the world and in this part of town. Please Mets, I can hear between the lines, go back to striving for mediocrity so we can criticize you for that.

Why so glum, chums? The bitter possibility of imminent success getcha down? You work for the NYC Sanitation Department and dread cleaning up all that orange and blue ticker-tape? Series tickets gonna eat into your Prozac budget?

Oh, poor you.

I'm not suggesting that the third world championship in New York Mets history is a sure thing for 2006. But it's surely a better thing to be making immediate strides toward that goal than not. If your best way of getting there is to take the team you had in 2005 and send them out there to build on what was just constructed, do that. If the most certain route to success is to replenish the bulk of your existing roster with in-house talent and take your best shot at '06 but understand that everything is on track to truly gel in '07 and beyond, do that.

But if you're already dealing with a fairly veteran team with a finite shelf life for certain of its key assets and you have reason to doubt the efficacy of your replenishments, then do this:

Trade for Carlos Delgado. Sign Billy Wagner. Rinse, repeat for a catcher and a second baseman and a lefty reliever of some ability.

Are the Mets a “win now” team? Gosh, I hope so. They haven't won yet so I'm getting a little antsy. Might there be heck to pay if this doesn't work and the man who owns the team we root for takes a chunk of the money we give him and has to write checks to guys who didn't win now and won't win later? Absolutely. Life runs rampant with risk.

There's also the risk that things will go the way they're supposed to, that a Delgado will slug his well-spoken head off and that a Wagner will zip gas past his former teammates and other bad dudes who did in the last closer, a gent we will refer to, in honor of Mrs. W's favorite show, as the Phantom of the Bullpen. There's every indication that both players — both MET players, that is — are capable of effecting these actions in the coming season. Knock wood, the next season, too. If we're alive and well as people as well as fans in 2008, well, let's hope for the best.

I know, the pristine ideal is to be 99 and 44/100% pure, that the only team worth getting in a dreamy lather over is nine men up from Norfolk magically coalescing in Flushing. If that's your soapbox subject, I join you in wishing that happens someday. But if the Mets hadn't traded for Delgado and signed Wagner, it wouldn't have happened in 2006 or 2007.

We've got Reyes. We've got Wright. That's two out of eight position players who were jewels of the system. That's not so bad if you realize that the Mets farm has produced more alpacas than it has studs this past decade.

Quick, who was the last homegrown non-pitcher to be cast off by us only to come back and make us cry? My guess is Preston Wilson, and he went for Piazza, so save your tears. Jason Bay doesn't count since he was not homegrown, just badly undervalued and mishandled. I could be missing someone, but who's out there with a bat, a glove and a Met pedigree?

Justin Huber? Jason Phillips? Vance Wilson? Ty Wigginton? Is Alex Escobar still rehabbing somewhere?

If you hadn't noticed, the Mets have produced almost no position players of distinction since Hundley and Alfonzo and maybe Payton — save, hallelujah!, for the incumbent shortstop and third baseman. That's a drought. That's the reason the Mets fired their head of scouting and are reorganizing their minor league infrastructure. Reyes and Wright are aberrations. Everybody else is a crapshoot.

So the options are hang on to the Mike Jacobses until they flourish or they don't (track record indicating they won't) or go about building a winner, even if the building is, heaven forefend, accelerated. Trade for Delgado. Sign Wagner. Pick one of those catchers. Check out Grudzielanek for a year or two. And start drafting and developing a lot better than has been the case since Buddy Harrelson was waiting on his final growth spurt.

In the literal meantime, attempt to win now. I won't be offended. I promise.

Carlos Delgado and I have one thing in common, and it ain't income. What it is is at Gotham Baseball.

by Greg Prince on 28 November 2005 9:34 pm FoxSports.com's Ken Rosenthal is reporting the Mets have signed Billy Wagner, four years, $43 mil. Includes an option for a fifth year.

The hardest throwing, most effective, longest running left-handed closer most of us have ever seen is a New York Met. He will be handed ninth-inning leads in 2006 and beyond.

I've gotten worse news on November afternoons.

|

|