Welcome back to Faith and Fear in Flushing’s recently dormant series 3B-OF/OF-3B, an attempt to understand why the New York Mets have spent so much of their (and our) lives trying to fit guys who play one position well at a position where they inevitably less well. Or, if you care to be sanguine about it, we endeavor to celebrate the versatility of the now 83 players who played both third base and the outfield for the Mets.

Wayne Garrett was not one of those players. He was versatile enough, with intervals at second (where he made his major league debut in April of 1969) and short (he was the “6” in the famous 7-6-2 putout of Richie Zisk at home plate the night the Mets definitively thwarted the Pirates in September of 1973), but what he did he did in the infield. Yet we can’t talk about the 3B-OF/OF-3B dizziness that afflicted the Mets in the years that followed Garrett’s trade to Montreal without Garrett, because Garrett leaving seemed to open the floodgates to a whole new multipositional matrix. No fewer than eight Mets joined the ranks of third basemen-outfielders in the next seven seasons. You might say that Wayne Garrett, on his way out of town, had ushered us into the octagon.

The self-perpetuating mythology that the Mets of their first two decades could never find a permanent third baseman tended to ignore the contributions of one Wayne “Red” Garrett, probably because the Mets themselves tended to ignore the contributions of one Wayne “Red” Garrett. Between May 4, 1969, and July 16, 1976, the New York Mets played 1,202 games. Wayne played third base in 711 of them, a clear majority. This includes 1971, when the redhead was serving his country until July in the Army Reserve as part of the last generation of ballplayers who had to fulfill such commitments. When he was available to play across his eight seasons as a Met, Garrett played the lion’s share of third, at first sharing time as a rookie with veteran and poet laureate Ed Charles, then threading appearances around imported answers Joe Foy, Bob Aspromonte, Jim Fregosi and Joe Torre.

“They tried to get a third baseman every year I was there,” Garrett reflected a couple of months after he was no longer a Shea Stadium staple. “I always felt if I didn’t have a good year, I wouldn’t be back.”

When he played his 711th game at third for the Mets, Wayne held the franchise record by several miles (Charles was second at 247). To this day, Wayne Garrett is the only Met to have played third base for the club in more than one World Series. His longevity in the position in his time seeped beyond the borders of Shea Stadium. Every year from ’69 to ’76. Garrett ranked among the Top 20 third basemen in the National League in terms of games played. Only two other NL third-sackers maintained that kind of presence across those eight seasons: Doug Rader and Richie Hebner.

Tony Perez was switched from third base to first base after the 1971 season and never played on the left side of the diamond again. Ron Santo was traded from the Cubs to the White Sox following the 1973 season and retired after one year on the South Side. They were the cream of the NL’s third base crop when Wayne broke in. Their accomplishments might have won them the status of immortality eventually, with each man today enshrined in the Hall of Fame, but they weren’t immune to being told they were no longer their team’s third baseman. Wayne Garrett didn’t reside in their echelon. He was forever being told he wasn’t going to be the Mets’ third baseman. Hence, the importation of Foy in 1970, Aspromonte in 1971, Fregosi in 1972 and Torre in 1975.

In 1976, the message finally became official. On Friday night July 16 at Shea versus Houston, Wayne started at third, made two putouts and two assists, and went 0-for-2 before giving way to pinch-hitter Roy Staiger. Talk about symbolism. Staiger had staked out his Third Baseman of the Future territory with his big year at Tidewater in 1975. Roy and Wayne more or less shared the position for three months of ’76, with one or the other getting swaths of playing time at third, and Wayne filling in at second for a ten-day stretch spanning May and June. Perhaps to indicate the shift from Garrett, 28, to Staiger, 25, was incomplete, the start at third base on Saturday afternoon July 17 went to utilityman Mike Phillips. Garrett pinch-hit in that game, for starting shortstop Buddy Harrelson, after which Staiger entered for third base defense, moving Phillips over to short. Elsewhere in the box score of this all-too-typical 1-0 loss for Tom Seaver (he struck out eleven, giving up only a barely fair, barely gone first-inning homer to Cesar Cedeño, while Met bats provided no support for their ace), we find Dave Kingman in right, Jerry Grote behind the plate and Joe Torre having pinch-hit for Seaver in the eighth.

Jerry Grote was the Mets’ 28th third baseman.

Wayne Garrett was the Mets’ 40th third baseman

Joe Torre was the Mets’ 48th third baseman.

Roy Staiger was the Mets’ 50th third baseman.

Dave Kingman was the Mets’ 51st third baseman.

Mike Phillips was the Mets’ 52nd third baseman.

As of July 17, 1976, 52 different Mets had played third base since the club’s 1962 founding. Six of them were in this game.

Two days later, Wayne made his final appearance as a Met, striking out as a pinch-hitter for Ken Sanders on the night Kingman — in left — hurt his thumb diving for a fly ball off the bat of Atlanta’s Phil Niekro, not only not making the catch, but short-circuiting his pursuit of the National League home run title, perhaps the National League home run record. Dave had 32. Hack Wilson had 56 in 1930. The chase of history went out the window, as did Kingman’s chance to become the first Met to lead the NL in homers. With Sky King confined to what was then called the disabled list until September, another third baseman, Mike Schmidt, caught and passed him. Compared to losing their only true power source, the trade that went through the next day was relatively small potatoes. For a franchise that was in only its fifteenth season, however, it represented a milestone, something beyond the same old same old…even if there was an element of déjà vu all over again underpinning it.

The Mets were sending their all-time third baseman to Montreal. Garrett and center fielder Del Unser became Expos so Pepe Mangual and Jim Dwyer could become Mets. Newsday’s headline: “Revolving Door Ejects Garrett,” with Malcolm Moran reviving and slightly revising a lede that could have served any reporter covering this team since 1962. “For 15 years they have come and gone,” he wrote, “each one staying for a while to occupy third base at the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium.” As much as Garrett was the exception to the rule, the rule got him in the end. No Mets third baseman was safe.

DiamondVision was six years from existing, which was just as well, since Mets management in 1976 didn’t seem of a mind to produce a “THANKS WAYNE!” video. Manager Joe Frazier, trying not to get tossed from the revolving door himself as his team floundered double-digits from first place, referred to the veterans the Mets were jettisoning, each of whom carried a batting average in the .220s, as “deadwood,” adding that he considered his roster “pretty old. We’re stale in a few positions.” GM Joe McDonald was a little more diplomatic regarding the departed, choosing to talk up the youth and speed that would define the Mets’ lineup the rest of the way. So many times the Mets sought to supplant Wayne Garrett by bringing in somebody older. Now they did it with the homegrown Staiger, someone three years younger.

“I think Roy deserves a shot,” McDonald reasoned, “and as long as Garrett was there, the temptation was to play him.” Garrett, content to be wanted by the Expos as something other than a bad habit, didn’t apologize for his perennial resilience or continual attractiveness:

“Over here, they’ve always had the problems of third base, third base, third base. Now I’m out of the picture. Let ’em go ahead and get their third baseman. They’ve been trying to get one for eight years.”

They’d keep trying.

To helpfully warn us what would lie ahead between 1977 and 1983, Red did what Old Friends™ do. On September 29, 1976, in his first series back at Shea, Garrett crushed a grand slam off Tom Seaver to lead the Expos to a 7-2 win. It was Wayne’s first grand slam at any level. “I never hit one in high school or Little League or Babe Ruth or anything,” he said, and he couldn’t have been happier to have saved it for McDonald and Frazier. “It showed the management here about the trade.” As if Pepe Mangual (.186) and Jim Dwyer (.154) hadn’t shown them enough.

Seaver entered the night leading the league in ERA, but his old third baseman put an end to his chance to add another of those titles to his already brimming résumé. Tom would have to settle for finishing third in the category, just like the Mets in the standings, whose late surge to 86 wins nonetheless left them far from Schmidt’s first-place Phillies. Since 1969, when Tom and Wayne and all the Mets captured the world championship as well as the imagination of North America, the Mets expected better of themselves, even if we in the stands and watching from home kind of got used to them winding up stuck in the middle of the NL East pack. The 86-76 record looked better than it felt.

“It’s been that kind of year,” Seaver said without any cheer in evidence.

When it came to the Mets and “that kind of year,” Tom and we had no idea what awaited over the horizon.

When he did get on base, trouble awaited. After reaching on an error in the fourth inning at Candlestick Park on May 7, Roy came around to score from second on a single. Staiger had to slide to make it home. In doing so, his left hand was cut by Giants catcher Marc Hill’s left spike. Roy left the game and found his cut hand not improving, with swelling still a factor a week later. He’d be out ten days in all, during which time Grote — acknowledged over the previous decade as the best defensive catcher this side of Johnny Bench (and even Bench admitted he’d be the one to start working out as a third baseman if the two played on the same team) — exchanged his mitt for a glove and started eight of nine games at third base.

It wasn’t unprecedented. Jerry had played third twice for the Mets in 1966, three times in 1972 and twice more in 1973 (along with a turn in the outfield in ’72) — plus he had been Wayne Garrett’s roommate on road trips and might have picked up a couple of pointers along the way. Yet it was unanticipated. Then again, in 1977, anything seemed to go, especially the Mets’ chances of contending. They were off to a 10-18 start, their worst in ten years, when Jack Lang noted in the Daily News that Grote was serving as “the Mets’ 50th third baseman this season”. A little hyperbole was permissible, as the club had already cycled through Staiger, Phillips, Torre, the previous September’s callup journeyman Leo Foster and the lately acquired Lenny Randle at third. Grote made it six in twenty-seven games. Frazier, leaning on a 34-year-old catcher who had almost retired during the preceding offseason because of chronic back pain — Topps didn’t even bother to issue a card on his behalf in its ’77 set — to refamiliarize himself with terrain he hadn’t defended in four years, acknowledged, “We need Roy’s glove.”

He tried his luck with Jerry’s. “Grote,” Lang wrote, “doesn’t have great range, but he does have good hands and has played the bag before.” Still, an older catcher playing third base is a an older catcher playing third base. At Shea against the Giants, there was a bunt Jerry couldn’t handle, and versus the Dodgers, there was a Dusty Baker line drive beyond his leaping reach that earned back page prominence in the News, with an arrow printed by the ball to imply Grote may have been out of his depth. Lang’s more charitable assessment was, “The Mets were not hurt during Staiger’s absence,” judging Grote as having “filled in quite capably. He was as much of a whiz with the glove there as he is behind the plate,” where he was being eased out to make room for young gun John Stearns. Stearns was the Opening Day catcher and held down the position almost without pause into mid-May.

John had been waiting for his break since backing up Grote throughout his rookie year of 1975. “He’s a fiery guy, a real hustler,” his first Met manager Yogi Berra said of his prized prospect backstop. “I hate to sit him. I want him to play every day and if Grote gets hurt, he’s only one day away.” Patience wasn’t exactly the kid’s calling card. At the end of his freshman season, Stearns told Journal News reporter Al Mari that he was ready to ask for a trade if he wasn’t going to catch regularly. “Call it bad management, but I never got a chance here,” he said that September. “You can’t play every ten days and stay sharp. I know I can do the job up here.” In 1976, Stearns, still a Met, accepted the wisdom of having that chance at Tidewater, opting to get better at Triple-A rather than sit in frustration in New York. In 1977, he was back to stay at Shea and on his way to his first All-Star Game, minting his status as catcher of the present.

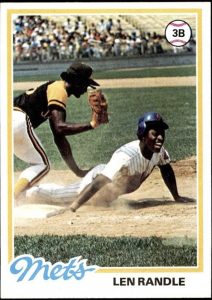

Another Met gaining a measure of satisfaction in a May that wasn’t otherwise merry was the new guy in town, Randle. Lenny was the avatar of the unanticipated. During Spring Training, he was a Texas Ranger, as he had been since the Rangers moved to Arlington from Washington in 1972. But the incumbent second baseman, 29, was falling victim to the same dynamic that saw Grote being nudged aside for Stearns. In the Rangers’ case, it was Bump Wills, who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated as the head of the class of NEW FACES OF ’77. It wasn’t a smooth transition in Randle’s view, and tensions rose between him and manager Frank Lucchesi. Lucchesi called Randle a punk for complaining. Randle fought back, literally, punching out his manager. Texas suspended the player.

Noticing there was a proven major leaguer in his prime as available as could be, and satisfied the Lucchesi incident was an aberration, the Mets took a flyer on Randle in late April and made him their new face of ’77. Frazier may have been in the same profession as Lucchesi, but was of a different mindset where Lenny was concerned. “I wish I had four or five more just like him,” Joe said, pleased with the erstwhile Ranger’s early Met production. The reception among teammates was almost universally positive. “Phenomenal,” Jon Matlack called him. “He’s got a magic wand. he’s great to have on the ballclub.” Ed Kranepool observed, “He’s playing great baseball. He hustles, he works hard. He’s not a problem on the club.”

One voice missing from the choir of hosannas was that of the Mets’ own incumbent second baseman, Felix Millan. Randle was versatile, but second base was where Frazier inserted him, which mystified Felix, who had served the Mets steadily since 1973. “Randle plays third and the outfield, and we have a catcher playing third base,” Millan said. “Why is he playing second base? Nobody’s told me anything. They just gave Randle my job. If they don’t want me here, they can trade me. I know I can still play every day for somebody.”

Millan was hardly the only Met looking for an exit from Shea Stadium as May was nearing June in 1977, but before the month was out, he no longer had to worry about a catcher playing third base. Staiger was healed and given his job back. Alas, the Mets continued to lose, and somebody was going to be given a ticket out of town. Not surprisingly, it was the manager. Joe Frazier was fired on May 31.

“I was ready to get out from under,” Frazier said of his 15-30 club. “It was driving me up a tree.” Ready to take on the same daunting oak of a challenge of steering the Mets out of last place was Joe Torre, initially hired as a player-manager (a designation that lapsed after a few weeks). The Mets had never had one of those before, but they also never had so much obvious dissension roiling their clubhouse. Millan wanted out. Matlack wanted out. Kingman was more unhappy than usual. And, not incidentally, Seaver’s ongoing conflict with M. Donald Grant was its own prime time drama.

“If Joe can do better with the team,” Frazier said, “more power to him, but I honestly didn’t see anything encouraging on the outskirts.”

The new Joe did one thing upon his taking over. He declared Lenny Randle would be his everyday leadoff hitter and third baseman (with Millan resuming everyday duty at second). Roy Staiger’s return from his hand injury, during which he batted .308 in eleven games, did not win him any long-term goodwill from the new manager, who knew a little something about playing third base. He also knew Randle, whose first few Met days included a couple of reps in left, was the hottest player Frazier bequeathed him, with an average that soared above .350. Staiger, for whom the Marc Hill cut was the deepest, was assigned to Tidewater for most of the rest of the season; come December, he was traded to the Bronx for Sergio Ferrer. Except for four games as a Yankee in 1979, Roy spent three years marooned in Triple-A, and was then through as a major leaguer. While he hadn’t made a great case for himself as the Met solution at third base, his tenure turned truncated once he experienced that injury to his hand after he slid home in San Francisco.

The batter who drove him in and ultimately toward dispensability? Lenny Randle.

Seaver and Kingman wouldn’t be the last stalwarts of the previous era to walk out the door in the months ahead. Felix Millan’s hold on second base ended with a body slam from baserunner Ed Ott in Pittsburgh in August. The next time he played ball, it would be in Japan (for two years sharing a league with post-Expo Wayne Garrett). Jerry Grote was swapped to the Dodgers before September, in time to make L.A.’s postseason roster. Jon Matlack would find his trade request granted in December when he was dispatched to Texas in a four-team deal that also turned 1973 holdover John Milner into a Pirate. Before 1978 got underway, one more extremely familiar face was missing, with shortstop Bud Harrelson — a Met so long he was probably hiding somewhere within the club’s skyline logo — traded in Spring Training to the Phillies.

Before any of that happened, there was the matter of welcoming to the Mets the six players acquired for their two icons on June 15, 1977, along with another player exchanged for one of the Mets’ lesser lights. Seaver’s bounty was a starting pitcher, Pat Zachry (1976 co-Rookie of the Year in the NL); two minor league outfielders, Steve Henderson (who was immediately promoted to the majors as a Met) and Dan Norman (who would make his debut in September); and a glove-first infielder who was never going to crack the starting lineup of the Big Red Machine, Doug Flynn. Kingman wrought a reliever, Paul Siebert, and a veteran utility guy whose upward mobility in the game was years earlier undermined by a gruesome outfield injury, Bobby Valentine. That third deal, the one not dominating front and back pages, saw Mike Phillips go to St. Louis for a former Red, Joel Youngblood.

If you’re scoring at home, Flynn, Valentine and Youngblood all arrived wearing various labels of versatility, and each would play some third base for the Mets in 1977, elevating the season’s total to nine Mets on third, or the most in any year since 1967…which also happened to have been the last time the Mets finished last before 1977. Their hideous 64-98 mark represented a dropoff of 22 wins from 1976, a year-over-year plunge that would stand as the worst in Mets history until the Mets of 2023 stumbled 26 games off their 2022 pace. With so many of their veterans gone or going, the Mets tried to sell themselves to an increasingly indifferent public as an agglomeration of promising youth. “Bring your kids to see our kids!” newspaper ads suggested. Four of the of the Mets’ kids posing — Flynn, Henderson, Zachry and Youngblood (alongside Stearns and Lee Mazzilli) — were June newcomers. Crowds failed to materialize in response. Shea Stadium attendance set a new low in 1977.

Ironically, the baseball team so often cited for its revolving door at third base featured as its best player in its worst year in a decade its third baseman. Not that Lenny Randle was all that interested in the irony. “I’m not into the history of the Mets,” he advised. “I know they had a guy named Joe Foy and Ed Charles there, but that’s about all.” Third Baseman No. 54 concluded his first season in Queens batting .304 in 136 games; sealing two walkoff wins with that magic wand Matlack admired; stealing 33 bases to establish a new club record; withstanding the weirdness of being at the plate as darkness descended over Shea Stadium amidst the July 13 New York City blackout (“I thought to myself, ‘This is my last at-bat. God is coming to get me.’”); and answering, at last with authority, the question of “Who’s on Third?” Randle was delighted to claim the spot as his own. “I’d like to play here forever,” Lenny said toward the end of a season that few remaining Mets fans wished would go on any longer.

What Randle really adored was his position, especially that it was his. Versatility may appeal to managers and general managers, but as a player who shifted among second, third and the outfield in Texas, “I never knew where I’d be,” he explained. “You take ground balls for infield practice and fly balls for the outfield and when the game starts, you’re so tired you’re lucky if you have seven innings in you. I love third base. I’m doing the best I can to master it.”

In a year when the Mets couldn’t have been less popular, Lenny was the Met most easily embraced. “You can’t help but love the fans in New York,” Randle said as he grew accustomed to his surroundings. “They pump you up. I feel I owe the fans my best as an entertainer. I don’t cheat them.” His second Met manager was just as crazy about him as his first. “Randle has great instincts to get to the ball,” Torre said in September. “He catches line drives, throws from his knees, he’s a scrapper. He has been all year. As of now, there is nobody on this team than can do the things Lenny can. He’s aggressive offensively and makes great plays defensively.” If not much else seemed bright about 1977, at least we could count on the productive and beloved Lenny Randle at third base, presumably for years to come.

Lenny Randle lasted one more year as a Met. It didn’t go as well as it did in 1977. Before 1978 was over, four more Mets who hadn’t yet taken a turn there would get a crack at the hot corner Randle would wind up vacating before Opening Day 1979. The revolving door was destined to spin quite a bit into the decade ahead and sputter in circles before the Mets would return to contention. And the mixing and matching of third basemen and outfielders — encompassing miscasting, reluctance, dismissiveness and a couple more catchers — was just getting going.

Yet again.

THE METS OF-3B/3B-OF CLUB

Turn and Face the Strange (1976-1977)

21. Lenny Randle

Mets LF Debut: April 30, 1977

Mets 3B Debut: May 8, 1977

22. Joel Youngblood

Mets 3B Debut: June 24, 1977

Mets LF Debut: June 27, 1977

PREVIOUS INSTALLMENTS OF 3B-OF/OF-3B

Chapter 1: 1962

Chapter 2: 1963-1969

Chapter 3: C-3B-OF

Chapter 4: 1970-1975

I loved Wayne Garrett. He was a hell of a clutch hitter down the stretch in 1973. When they got Randle, he immediately became my favorite Met, so much so, that I rooted for him when he became a Yankee for a few weeks in ’79.

I rooted for Kingman when he became a Yankee for the last 2 weeks in 1977 and he tore the cover off the ball, almost knocking down the fence in Detroit.

You beat me to the 1973 reference. He was the guy I wanted up there in any clutch situation. Tons have been written about 1973, but it seems he’s mostly overlooked (not here of course) as the main offensive mover and shaker of that stretch run.