We have reached a stop on the MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT journey that can’t be appreciated fully if you forget to pack nuance. This season wouldn’t rate as highly as it does with me if there wasn’t more to it than its unfortunate ending. It would likely rate a lot higher if the ending didn’t still feel so unfortunate.

Howie Rose welcomed a guest to his nightly talk show in the fall of 1988, a reporter from Sport magazine who explained he was working on a story about the state of the New York sports scene, part of a larger series of citycentric profiles the publication was planning. Howie, being the gracious host he was, let the writer borrow his platform for a couple of segments to interact with callers who would deposit their two cents of perspective in his notebook. In retrospect, the idea that a sportswriter would reach out to sports fans for what they thought about sports seemed novel. Pre-Internet, we were usually just the rabble, referred to as a veritable blob when referred to at all: “The fans seem to think…” Kudos to article author Rufus Sears for taking the extra step.

After listening to WFAN that night, I kept on the lookout at a newsstand near me in the months ahead for the issue of Sport that would include the New York story. Its cover date was February 1989. Its cover subject was Cindy Crawford, fronting Sport’s HOT SWIMSUIT ISSUE (wonder where they got that idea). I don’t know how many readers rushed past the supermodel’s picture for the table of contents and laid down their $2.50 only when they ascertained what else was inside, but one of them was me.

Pardon my moistened flipping finger, Ms. Crawford, but I need to get to why I purchased this magazine.

On page 42, the reader is informed New York sports are “the biggest and baddest” and that they “burn with passion”. In our boroughs, we are told, “the chances are surprisingly good that the woman heading down the avenue in navy-blue business suit and Nikes has a strong opinion on whether Mookie Wilson or Lenny Dykstra ought really to be starting for the Mets. It’s that kind of town. You take sports seriously, or you don’t ever completely fit in.” Municipally flattering enough, I suppose, and it’s nice to know Sport was focusing a little on a lady who didn’t have to wear a two-piece to be part of its editorial planning.

Why, yes, I did buy the swimsuit issue for the articles. Thirty-five years later, as I turned my Favorite Seasons focus to remembering 1988, I’d completely forgotten Cindy’s bikini turn, but I recalled a passage in Sears’s “Sport City Tours” piece so vividly that I had to purposefully trawl eBay for the first time in ages and search out the issue anew — so many subscription cards and cigarette ads! — to confirm I wasn’t imagining it. There it was, on page 46, where Sears, who self-identifies at the outset of the feature as “a New York fan,” shares his impression of what the New York Mets are all about in the aftermath of 1988:

Why, yes, I did buy the swimsuit issue for the articles. Thirty-five years later, as I turned my Favorite Seasons focus to remembering 1988, I’d completely forgotten Cindy’s bikini turn, but I recalled a passage in Sears’s “Sport City Tours” piece so vividly that I had to purposefully trawl eBay for the first time in ages and search out the issue anew — so many subscription cards and cigarette ads! — to confirm I wasn’t imagining it. There it was, on page 46, where Sears, who self-identifies at the outset of the feature as “a New York fan,” shares his impression of what the New York Mets are all about in the aftermath of 1988:

The Mets drew even more than the Yankees, a record three million plus, despite the fact that yupsters and Janey-come-latelies seemed to lose interest last season. The team’s sweaty, dusty hubris had somehow lost its chat appeal at the water cooler. People grew tired of the whining from the manic “tablesetters,” Dykstra and Wally Backman; though solemn and productive Kevin McReynolds was increasingly mentioned as a role model. The team was subtly handed back to its Queens constituency, the muscled street kids and their bespectacled middle-class counterparts. in a comforting way, the Metsies are reverting back to primary ownership by the Queens fans who have supported them since long before any miracles, fans who’ll be there in the cold and the rain, no matter what. The Manhattan-forged hipness and “heat” has quietly dissipated, and they’re once against part of the streets where generations of bottlecaps are melted into the asphalt and the prototypical fan is a portly old presser of suits taking his ease on a sidewalk milk crate on a hot August afternoon while the game crackles over WFAN.

I read this summation in early 1989, and couldn’t connect it to the reality I knew and sensed about the Mets at the end of 1988 (and that’s with my relatively svelte, Yankees fan grandfather having been an actual rather than abstract dry cleaner in Jackson Heights; he was long gone by then, but Prince Valet was still open and pressing suits on 82nd Street). I reread this summation in early 2024, and I still can’t. It didn’t embody the Mets zeitgeist I had lived through, which may be why some of the rhetorical flourishes — “muscled street kids” and “subtly handed back to its Queens constituency” stood out — have lived under my skin for three-and-a-half decades. Perhaps the author, under deadline pressure, simply thought it all sounded good and decided all of it was true.

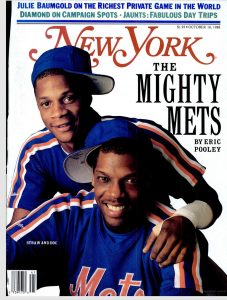

To me, the Mets of 1988 were, if anything, verging on too big, too popular, too much of an ongoing event. They were almost too good for their own good, or our own good. Maybe 1988 was the original manifestation of the dreaded 21st-century lament, “This is why we can’t have nice things.” We had the nicest thing there was in baseball. It proved too nice to last.

“This must be just like living in paradise,” David Lee Roth wailed in the leadup to the 1988 season. Who knew he was a Mets fan? Then again, it seemed like almost everybody was in those hard-earned days. We’d persevered through the barren late ’70s and the false-start early ’80s. We’d spent seven years at the bottom of the National League East and alone at Shea Stadium. Now we were where the party was. Nineteen Eighty-Eight was the future we as Mets fans dreamed of living in before such a Metscape seemed possible. We went from having basically nothing to owning essentially everything. This was not our younger selves’ franchise.

“This must be just like living in paradise,” David Lee Roth wailed in the leadup to the 1988 season. Who knew he was a Mets fan? Then again, it seemed like almost everybody was in those hard-earned days. We’d persevered through the barren late ’70s and the false-start early ’80s. We’d spent seven years at the bottom of the National League East and alone at Shea Stadium. Now we were where the party was. Nineteen Eighty-Eight was the future we as Mets fans dreamed of living in before such a Metscape seemed possible. We went from having basically nothing to owning essentially everything. This was not our younger selves’ franchise.

In no particular order, we had…

SUCCESS: Ninety or more wins every year as a rule for five consecutive years; only two other National League teams had as many as two such years between 1984 and 1988, and nobody else in the NL could claim as much as a winning record every season in that span. Plus, there was a world championship in the middle of all that, assuring that for eternity nobody could say about those spectacular Mets teams that they never won the big one. You could hardly blame the Mets for playing up their arc as “Excellence. Again and Again.” They were telling it like it was.

CONTINUITY: The promising likes of Randy Myers, Dave Magadan, David Cone and Gregg Jefferies — truly promising, not simply “future stars” fodder for the back page of the official yearbook — all had to wait for their big break. Myers emerged as the primary closer despite the presence of two proven World Series firemen on the roster. Magadan had to sit behind a perennial Gold Glover and revered clutch captain at one position and a 30-30 man at another. Cone was depth for an already deep rotation. And Jefferies was merely the shiniest object in anybody’s farm system. Through the draft and through trades, the Mets were replenishing while winning, having “created a minor league farm system that is now producing more talent than they know what to do with,” per a glowing Manhattan, Inc. profile that ran shortly after Sport’s New York analysis.

ESTEEM: The Mets’ “build-from-the-bottom organization” was termed “the model that other teams,” the Twins and Rangers among them, “say they emulate,” per Manhattan, Inc., which hailed the Mets as a blueprint to follow for both baseball and business.

ALLURE: The Dodgers were traditionally the only team that could be relied on to draw more than three million fans, thanks in great part to beautiful weather. It rarely rained in Southern California. Queens could make no such claim, but it had a team almost impervious to climate conditions. In 1987 and 1988, the Mets became the first non-L.A. franchise to register paid attendance over three million in back-to-back years — and this was when only people through the turnstiles rather than total tickets sold were counted. This was also when occasional doubleheaders were still scheduled as a matter of course; rainouts occasionally had to be rescheduled within single-admission doubleheaders; and there weren’t promotional come-ons practically every weekend to goose the gate. Nationally, the Mets aired over NBC and ABC as much as the networks could put them on, and locally, they were literally the talk of the town. Their presence on 1050 AM was the foundation for all-sports radio, and no athletic enterprise drew more calls to WFAN than the New York Mets.

NEAR FLAWLESSNESS: To be fair, I generally lacked confidence in our various lefty specialists after Carlos Diaz was traded with Bob Bailor to land Sid Fernandez, though Bob McClure seemed like a pretty sharp pickup coming out of the break in ’88. I’ll also cop to a lingering wistfulness for Bailor’s versatility. Otherwise, what were we missing? We had glittering superstars, unquestionable frontline ability, superb backups adeptly deployed, starters and relievers to count on, a regenerative talent pipeline, in Davey Johnson a manager who rarely took lose for an answer and, per Manhattan, Inc. once more, “the best-run organization in baseball”. Ownership facilitated Frank Cashen, Joe McIlvaine and Al Harazin and didn’t make a public-facing jerk out of itself. The stadium was freshened up with those eye-catching neon figures along the exterior. If you weren’t one of the three million-plus rushing to Flushing, Tim McCarver continued to bring out the best in Ralph Kiner on TV, and by the end of 1988, WFAN’s signal, beaming Bob Murphy and Gary Thorne during games that were bracketed by Howie Rose’s must-listen Mets Extra before and after, now emanated from 660 AM, was stronger than ever.

If this wasn’t paradise, then it was close enough for the earthbound Mets fan to mistake it for such. Then again, things could have been a little more heavenly in our version of nirvana. Just one world championship despite all those regular-season wins? Just two division titles? Only one Cy Young winner, and he had to miss time the year after to enroll in drug rehab? No MVPs despite some outstanding individual seasons? The flawlike down notes were a function of day-to-day baseball. Your team, no matter how good, never goes 162-0. The 1988 Mets couldn’t even put 162 games in the books, getting rained out twice without convenient makeup dates. Of the 160 they played, they required every last one of them in order to reach triple-digits in wins. The nerve!

If this wasn’t paradise, then it was close enough for the earthbound Mets fan to mistake it for such. Then again, things could have been a little more heavenly in our version of nirvana. Just one world championship despite all those regular-season wins? Just two division titles? Only one Cy Young winner, and he had to miss time the year after to enroll in drug rehab? No MVPs despite some outstanding individual seasons? The flawlike down notes were a function of day-to-day baseball. Your team, no matter how good, never goes 162-0. The 1988 Mets couldn’t even put 162 games in the books, getting rained out twice without convenient makeup dates. Of the 160 they played, they required every last one of them in order to reach triple-digits in wins. The nerve!

Seriously, the 1988 Mets took over first place in early May and never surrendered it, but they dared to not altogether put away their primary competition — the young and relentless Pittsburgh Pirates of Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla — until late August. The Mets thwarted the Pirates in every head-to-head showdown through the summer, but the Bucs remained close enough in the standings to make the Mets sweat. We’d convinced ourselves the Mets were made of Right Guard and were therefore never supposed to perspire. A 30-11 start to the season indicated the rest of the year would be a breeze. But the Mets didn’t always hit as well as they pitched, and if Darryl Strawberry wasn’t blasting one of his 39 homers, or if one of the pitchers had an off night, the 24-man roster had a tendency to be human. Age was also catching up with good old (emphasis on the latter) Gary Carter, whose three-month wait for his 300th homer made him seem like less than a stickler for promptness, and Keith Hernandez, whose hamstring betrayed him and sent him to the DL. A few wins, a few losses, rinse and repeat. For about three months, the mighty, mighty Mets played at a .500 clip. Their leadership didn’t like what it was seeing.

Seriously, the 1988 Mets took over first place in early May and never surrendered it, but they dared to not altogether put away their primary competition — the young and relentless Pittsburgh Pirates of Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla — until late August. The Mets thwarted the Pirates in every head-to-head showdown through the summer, but the Bucs remained close enough in the standings to make the Mets sweat. We’d convinced ourselves the Mets were made of Right Guard and were therefore never supposed to perspire. A 30-11 start to the season indicated the rest of the year would be a breeze. But the Mets didn’t always hit as well as they pitched, and if Darryl Strawberry wasn’t blasting one of his 39 homers, or if one of the pitchers had an off night, the 24-man roster had a tendency to be human. Age was also catching up with good old (emphasis on the latter) Gary Carter, whose three-month wait for his 300th homer made him seem like less than a stickler for promptness, and Keith Hernandez, whose hamstring betrayed him and sent him to the DL. A few wins, a few losses, rinse and repeat. For about three months, the mighty, mighty Mets played at a .500 clip. Their leadership didn’t like what it was seeing.

Cashen: “In all my years in baseball, I’ve never seen a club with this much talent play so poorly for so long.”

Hernandez: “This team plays like a bunch of Little Leaguers.”

Whether you tuned into the games, read the papers or listened (too much) to the FAN, you knew the Metsopotamian natives were restless, too. The Mets were less cheered for their stranglehold on the top of the division than questioned for not pulling away from the pack. On August 14, the Mets swept the Expos, who’d briefly nosed ahead of the Pirates for second place, in a Banner Day doubleheader at Shea (the last time the Mets ever scheduled a twinbill in advance rather than out of contingency). Montreal was now 6½ games back. Pittsburgh sat five out. “Maybe,” an unidentified Met told Bob Klapisch in the News, “that’ll keep the animals off our backs for a while.”

A little harsh, but that’s living in paradise in real time, when the players, according to ace observer Klapisch, were “weary, plain and simple” of the expectations and critique surrounding them. Howard Johnson told Bob, “Imagine we’re apologizing for being five games up.” Klap’s colleague Phil Pepe, who’d been around baseball clubhouses for a long time, chimed in, “What the Mets have been this season is an enigma, a puzzlement to those who follow them closely. […] They were stamped with the mark of greatness after the first month of the season, an aura they have not been able to maintain with any consistency.”

A little harsh, but that’s living in paradise in real time, when the players, according to ace observer Klapisch, were “weary, plain and simple” of the expectations and critique surrounding them. Howard Johnson told Bob, “Imagine we’re apologizing for being five games up.” Klap’s colleague Phil Pepe, who’d been around baseball clubhouses for a long time, chimed in, “What the Mets have been this season is an enigma, a puzzlement to those who follow them closely. […] They were stamped with the mark of greatness after the first month of the season, an aura they have not been able to maintain with any consistency.”

Again, five games up.

Whatever expectations were going unmet, the fans were still coming out to meet the Mets — a lot. Banner Day represented the eleventh sellout at Shea in the Mets’ previous twelve dates. Season ticket package sales had been so robust the Mets had to limit them so they’d have enough to fill the postseason orders most everybody was anticipating. Getting a ticket for most any game at the height of the Mets’ attractiveness was tough enough. Getting what was considered a good one was nearly impossible unless you’d bought one of those packages or wrote away during the winter as soon as individual ducats went on sale. The crowds, as might be expected in New York when demand is high, skewed more corporate than ever. Even Harazin, who you’d figure would be happy to take the money from whatever entity was willing to pay it, admitted to Manhattan, Inc., “It’s harder for Joe Fan, for his family, to come out and buy a ticket for a ballgame. I don’t know what to do about that.”

Whatever expectations were going unmet, the fans were still coming out to meet the Mets — a lot. Banner Day represented the eleventh sellout at Shea in the Mets’ previous twelve dates. Season ticket package sales had been so robust the Mets had to limit them so they’d have enough to fill the postseason orders most everybody was anticipating. Getting a ticket for most any game at the height of the Mets’ attractiveness was tough enough. Getting what was considered a good one was nearly impossible unless you’d bought one of those packages or wrote away during the winter as soon as individual ducats went on sale. The crowds, as might be expected in New York when demand is high, skewed more corporate than ever. Even Harazin, who you’d figure would be happy to take the money from whatever entity was willing to pay it, admitted to Manhattan, Inc., “It’s harder for Joe Fan, for his family, to come out and buy a ticket for a ballgame. I don’t know what to do about that.”

I was an infinitesimal fraction of the Mets’ paid attendance in 1988. I wasn’t connected to any corporation, I didn’t mail in any checks before the season started, I wasn’t brimming with disposable income. I just wanted to go to a game now and then. On a Saturday night in early July, I went alone. I hadn’t been to a game yet all year, so I invested in two of the less expensive tickets at the advance window on spec when I found myself driving by Shea a few days earlier. Couldn’t convince anybody to join me at the last minute. There went a ticket that didn’t count as paying and attending; oh well. I drove to the general vicinity of the stadium on my own, got stuck in traffic on the Cross Island while Belmont was letting out, wound up having to park far away as well as sit far away. Unnecessary second seat notwithstanding, I judged the outing worthwhile. Doc pitched a complete game. Darryl and Hojo homered. The Mets won with ease. Long before I came to embrace the pleasures of a solitary outing, I felt kind of lonely among 44,715 presumably sated patrons, but the baseball aspect of it was definitely rewarding, no matter how small the star players looked from the Upper Deck in left field. As I walked and walked and walked some more back to my car somewhere in Corona, I knew I had just watched my team rise to 51-29 after their first eighty games, a pace they almost replicated in their next eighty games en route to finishing 100-60, a full fifteen up on the second-place Pirates. What had everybody been complaining about?

About a week after quieting “the animals,” the Mets roared to life in a manner that nobody could question. In Los Angeles, with Bud Harrelson filling in as manager when Davey Johnson needed to leave the team to tend to his ailing mother, the team’s senior man, Mookie Wilson, was entrusted anew with the full-time center field job. Platoon partner Lenny Dykstra sat and Mookie hit: 6-for-15 in a three-game sweep of the Dodgers, setting the stage for one of the great combined individual and team stretch runs in franchise history. Mookie batted .376 in his final 31 games, as the Mets, on a 29-8 tear, buried the Buccos. One of the team’s least experienced hands played an outsize role in the leveling up as well. Infielder Gregg Jefferies, who sipped a cup of coffee in 1987 after twice being named Baseball America’s Minor League Player of the Year, was recalled for good in late August and lit up National League pitching for the next several weeks. Throw in David Cone’s march to twenty wins, and it seemed there was nothing this team didn’t have or couldn’t do.

Their lead kept growing, their talent kept showing, and the vibe surrounding them turned inevitable. They’d face a much lesser team in the playoffs, the 94-67 Dodgers, from whom they’d already taken ten of eleven, and the looming Mets-A’s World Series resonated with classic overtones. Those of us in the stands for the final regular-season home game (I lucked into Field Level seats for my second and last Shea appearance of the year) figured we were stating a fait accompli as we chanted, BEAT L.A.!

It was a delight being embedded within the 42,099-person choir offering an amen to our conquering heroes, but I think I had my real celebration slightly in advance of the September 22 division-clinching versus the Phillies. I was standing on the porch of my family’s house, looking to the sky as sunset neared. I must have heard something on the news about the autumnal equinox and decided the stars were aligning in our favor. Fall was coming. For the fourth time in the history of this planet, the New York Mets, my New York Mets, were about to be crowned champions of the National League East, the only designation that got a team somewhere at the end of the regular season back when there were only four divisions.

It was a delight being embedded within the 42,099-person choir offering an amen to our conquering heroes, but I think I had my real celebration slightly in advance of the September 22 division-clinching versus the Phillies. I was standing on the porch of my family’s house, looking to the sky as sunset neared. I must have heard something on the news about the autumnal equinox and decided the stars were aligning in our favor. Fall was coming. For the fourth time in the history of this planet, the New York Mets, my New York Mets, were about to be crowned champions of the National League East, the only designation that got a team somewhere at the end of the regular season back when there were only four divisions.

My first undeniable specific memory of the Mets, my Mets, doing something was becoming NL East champions the first time, in 1969. This, now, was my twentieth season as their fan. We won 100 games my first year, topped off by the World Series. We were nearing 100 wins again. It had been a pretty lousy non-Mets year for me personally. I’d reached a professional crossroads I didn’t know how to traverse, my mother was having serious health problems, I was more than a thousand miles away from my college-going girlfriend. At 25 years old, I was letting circumstances too often overtake me. On the baseball side of life, the realm where I sought solace, I was as guilty as any Mets fan of turning my expectations into assumptions. Of course the Mets were supposed to win a division. Of course I believed they should be closer to closing in on 160-0 than 100-60. Yet alone on the porch, alone with my thoughts, as alone as I’d been at that game in July, I looked to the sky and pictured my team pulling together. They were about to gain one of those little asterisks next to their name in the standings. They were going to be champions of something essential, and they’d be poised over the next few weeks to be champions of everything, returning to the apogee they’d attained in 1986 and compensating for what felt like the cosmic mistake of 1987. We should have been striding toward our third consecutive world championship. I was willing to settle for two out of three.

I hadn’t had that much to feel good about in 1988. The Mets shaking off whatever held them back before Mookie and Jefferies and Coney led their charge to the forthcoming champagne shower(s) filled me up. This first clinching would merely begin to make it official.

In New York magazine on the eve of the NLCS, Keith Hernandez issued a warning: “If we don’t win the playoffs, it all goes down the fucking toilet.” Thirty-five years later, to Mike Vaccaro in the Post, Keith reflected, “Even when things were rolling, you could feeling something was just…off. Just a little bit off.”

In New York magazine on the eve of the NLCS, Keith Hernandez issued a warning: “If we don’t win the playoffs, it all goes down the fucking toilet.” Thirty-five years later, to Mike Vaccaro in the Post, Keith reflected, “Even when things were rolling, you could feeling something was just…off. Just a little bit off.”

A little bit was all it took to lose the pennant to Los Angeles, four games to three. Few any longer seem to remember the three wins, though they were rousing and reassuring in their time, a reminder that whenever you doubted the 1988 Mets, they were capable of demolishing your skepticism. They chased Orel Hershiser, he of the record-setting shutout string, in the ninth inning of Game One, Gary Carter doing the key RBI honors. They rollicked in the rain at Shea in Game Three. And with their backs to the wall in Game Six, Cone delivered a complete game five-hitter, supported by Kevins McReynolds and Elster at the plate.

Not pictured: Cone firing up the Dodgers for a Game Two ambush with his acerbic comments in a ghostwritten column following Game One; Carter stranded on third after the gimpy catcher tripled with nobody out in the sixth inning of Game Four, the Mets’ two-run lead left unexpanded; Gooden protecting that two-run lead into but not through the ninth (what, Doc was gonna give up a two-run homer to Mike Scioscia?); baserunners galore not being driven home in the bottom of the eleventh and the bottom of the twelfth, sandwiching a Kirk Gibson home run that spelled the difference in what became the pivotal Game Four loss; the Game Five matinee defeat that seemed to start about ten minutes after the Game Four post-midnight loss; and the Game Seven debacle during which Hershiser couldn’t have been more Hershiser and the Mets couldn’t have been more what their skeptics said they were when they lagged during the summer.

That it was the Dodgers who beat the Mets struck me as symbolic. During the Mets’ down years, when an appearance on Monday Night Baseball made you think somebody in an ABC Sports production truck must have pushed a wrong button — because since when are we on Monday Night Baseball? — the Dodgers reigned as the flagship team of the National League. They didn’t win every year, but they were always atop the list of teams everybody took seriously. Outlasted the Reds and the Pirates following the end of the 1970s. Overshadowed the Phillies and the Astros past the dawn of the 1980s. A bigger deal than everybody. Most fans through the gate. Most stars on the field. Most mentions on sitcoms and such when somebody writing a script wanted to invoke a baseball team by instantly recognizable name. I’d always attributed that to so much of TV being based in Hollywood, but you couldn’t deny the enormity of the Dodgers’ identity. Yet by 1988, we’d all but usurped their position as the team people thought of when they thought about baseball. We had the crowds and the stars and the buzz. They’d had a couple of off years while we’d established our ascendancy. They rode Hershiser, Gibson and gumption to the NL West flag, but that was going to be it as a storyline. Adios, Chavez Ravine; cachet is setting up shop at Shea. How odd, I thought, despite our superior record, that they were framed as the big underdog against us, given that they were the Dodgers. If we won this playoff battle, their name would no longer mean what it had. We would be, once and for all in my thinking, the Mets to everybody.

But we switched roles at the wrong time, in October. When they went on to win the World Series over Oakland, Vin Scully (their announcer) told a national audience, “Like the 1969 Mets, it’s the impossible dream revisited.” Freaky Friday had never been so cruel.

So, did it all go down the toilet? In collective recall, pretty much. Vaccaro wasn’t interviewing and writing about the 1988 Mets in 2023 to celebrate the thirty-fifth anniversary of 100 victories or the fourth division title or those three swell NLCS victories. The homer Scioscia indeed hit off Gooden was framed as the dividing line between how great things had been for the Mets up to that pitch and how it was never quite the same again. This familiar angle tilted toward tabloid black & white (the Mets legitimately challenged for division titles in 1989 and 1990), but the evidence is compelling. The Mets’ next playoff engagement wouldn’t take place for more than a decade, and except for 2006, they haven’t since entered a postseason as the consensus favorite in their league. No New Yorker true to the orange and blue need be reminded the Mets fumbled away Biggest Thing In Town status by the mid-1990s and have never grasped it for more than a few fleeting minutes in the current century. When Hernandez and Ron Darling are nudged by Gary Cohen to remember 1988 in the SNY booth, they invariably respond with regret and recriminations. When the year’s accomplishments are remembered anywhere, it is only as prelude to spotlighting the failure to accomplish more.

So, did it all go down the toilet? In collective recall, pretty much. Vaccaro wasn’t interviewing and writing about the 1988 Mets in 2023 to celebrate the thirty-fifth anniversary of 100 victories or the fourth division title or those three swell NLCS victories. The homer Scioscia indeed hit off Gooden was framed as the dividing line between how great things had been for the Mets up to that pitch and how it was never quite the same again. This familiar angle tilted toward tabloid black & white (the Mets legitimately challenged for division titles in 1989 and 1990), but the evidence is compelling. The Mets’ next playoff engagement wouldn’t take place for more than a decade, and except for 2006, they haven’t since entered a postseason as the consensus favorite in their league. No New Yorker true to the orange and blue need be reminded the Mets fumbled away Biggest Thing In Town status by the mid-1990s and have never grasped it for more than a few fleeting minutes in the current century. When Hernandez and Ron Darling are nudged by Gary Cohen to remember 1988 in the SNY booth, they invariably respond with regret and recriminations. When the year’s accomplishments are remembered anywhere, it is only as prelude to spotlighting the failure to accomplish more.

Gregg Jefferies’s surefire superstardom never quite ignited. Kevin McReynolds — dubbed “the Stealth Bomber” by Roger Angell — didn’t endure as the role model Sport magazine said he was. Within twelve months of the final out of the Dodger series, none among feisty 1986 ring-bearers Wilson, Dykstra, Backman, Carter and Hernandez (not to mention Lee Mazzilli, Roger McDowell and Rick Aguilera) would remain Mets. We were already missing the fiery leadership of Ray Knight. We’d soon realize we also missed the sparks set off by Kevin Mitchell, despite strong, silent McReynolds’s steadiness and productivity in the two seasons that followed the exchange of those Kevins. We probably missed everything about Bobby Ojeda, lost for the playoffs to a hedge-trimming fiasco, more than we realized. Knight, Mitch and Bobby O were intrinsic elements of winning it all two years earlier. As was just about everybody that singular year, with nobody, despite all the talent the organization could boast of having collected, proving easily replaced in the scheme of Met things. In August, Hojo had stressed to Klapsich, “1986 will never happen again.” It surely didn’t happen in 1988. Coming sort of close, then reasoning sometimes you’re left with nothing to do but shrug and say Shea la vie wasn’t going to wholly satisfy the Queens constituency, not even this member of its Long Island branch. A hundred wins, a division title and an aura that doesn’t come around very often isn’t nothing. It also wasn’t everything.

The era in which the 1988 Mets thrived and fell short was indeed the future we wanted. Just not every day of it. Paradise isn’t always what you imagine it might be.

The era in which the 1988 Mets thrived and fell short was indeed the future we wanted. Just not every day of it. Paradise isn’t always what you imagine it might be.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

Wasn’t 1988 also when Seaver’s number retirement ceremony happened? That was fun.

Scioscia’s HR WAS the dividing line — it was the difference between going up 3 games to 1, and the eventual 2-2 tie it became, which was the beginning of the end. It still hurts.

While Keith and Ron have 1988 regrets, the impression I get from Keith in the booth is that 85 and 87 hurt even more. Keith has said he felt they should have caught the Cards in 85, and repeated the championship in 87. Maybe it’s all wrapped up in one giant disappointing package, but hey — we (and they) will always have 1986.

I don’t know how you do it, Greg — I really, REALLY didn’t want to read this one.

Well, as the patron saint says:

*SIGH*

Somewhere in my house, I have a regular season game giveaway gym bag from, I suppose, 1989, “celebrating” that fact that the Mets had the best record in MLB (NL, maybe?) from 1984-88.

5 years of excellence, or some such nonsense.

It had a 1 at its centerpiece.

Yes, it did. Does.

1988 was the first year that the dreaded label “underachievers” appropriately applied to the Mets after the debacle that was the NLCS. The future was so bright throughout 1988 season until then that we had to wear shades. It is just another reminder of how fleeting success has been for our team, and how important it is to enjoy the good times in real time as they unfold. It seemed inevitable (prior to 1989) that Doc and Darryl would be our backbone for at least the next 10 years or so, that Carter and Hernandez would continue to perform until our vast farm system would provide replacements, and that much continued success was on the horizon. Alas, it was not meant to be. They also did lose a bunch of mojo when they swapped Kevins, since watching the competent if innately unspectacular Kevin McReynolds play was as scintillating as watching the Lawrence Welk show.

Ray Knight was a huge part of the personality of that 1986 team. When they didn’t resign him, that was the end of that era. We don’t know what a 1987 Ray Knight would have done with the Mets, but that was a big loss (not to mention the Kevin swap).

Ah, yes, the Underachievers.

That’s what they are, and what they will always be. They had no discipline off the field, and no discipline on the field. And no discipline in the manager’s office.

Glad Keith is facing up to it.

These late 80s retrospectives are all so well written but also bring me a sense of longing for a bygone era that will never return.

As much as I love Keith for what he is… I always felt like his perspective of “1987 was the missed opportunity, 1988 was always doomed” is colored by his personal decline. The ’88 team was really really good! If Ojeda is available for the playoffs, if Cone keeps his mouth shut, if Davey pulls Doc before the 9th in Game 4… any one of those flips the NLCS. Even a loss to the powerhouse A’s in the WS makes this a “passing of the torch” year rather than slapping the underachievers label on the team. Maybe Strawberry doesn’t go to LA, maybe they never make the Juan Samuel trade, maybe maybe maybe… but in this universe, it will always be tarnished by what could’ve been…

Also, this is why I hate the stupid expanded playoffs. Under the current structure, the Mets would’ve qualified every year from ’84 to ’90! That’s a pretty different narrative than what actually happened.

This year’s Arizona team reminded me a lot of the ’84 Mets… a fun young team that clearly wasn’t the best in the NL yet won a bunch of coin flip playoff series, instead of being a year or two away from a true contender. What’s even the point of the playoffs if we’re rewarding mediocrity?

Hey, with all this talk regarding the see-through pants, it’s just MLB trying to cut a deal with the LOGO network.

That Cone article – and the gardening accident.