This here’s a story about Charlie Williams, a young pitcher who seemed destined for if not big, then definitely specific things. Consider what can be gleaned about C.W. from his C.V.

• Born in Flushing fourteen years before ground was broken on the stadium that would make that Queens village world-famous.

• Matriculated at Great Neck South High School, a few stops east of Shea as the Port Washington line of the Long Island Rail Road flies.

• Signed by his hometown New York Mets out of a college whose name was the same as the pitcher who was traded for the catcher who would be the first he’d throw to in the majors.

• Celebrated his 22nd birthday the day his parent club commenced their first World Series, though he wasn’t nearly advanced enough to join them yet.

• Spent the following season mowing down hitters in the Double-A Texas League, pitching to a 12-5 record at Memphis, woven among a tapestry of names that make a certain strain of Mets fan swoon: Jim Bethke, five years removed from the time he became the first and only 18-year-old to take the mound as a Met; Les Rohr, the first No. 1 pick the Mets ever selected in an amateur draft; Bill Denehy, who’d been traded by the Mets to the Senators for the managerial rights to Gil Hodges and who’d since been traded back; Don Rose, one of three men assigned to accompany Nolan Ryan to California in the quest to acquire Jim Fregosi; Tommy Moore, who’d later be thrown into the deal that would make Brooklyn’s own Joe Torre a Met; and Lute Barnes, who — like Moore — I’m told is one of the handful of Mets to never have an official baseball card printed with his image during the course of his professional baseball career (though Moore’s picture finally made it into the 1990 Pacific Senior League set via card No. 148 a dozen years after he was released by the Baltimore Orioles).

The most accomplished player, eventually speaking, to perform for those 1970 Memphis Blues, was John Milner, the slugging first baseman/outfielder who blasted 94 home runs as a Met, including 23 during the pennant-winning campaign of 1973. The next-most accomplished player and the pitcher who would come to possess the thickest MLB credentials from that staff?

Charlie Williams, the kid from Flushing.

As Williams’s path would have it, he wouldn’t be known for what he did directly after his promotion from the Memphis Blues to the New York Mets. Hopping over Triple-A Tidewater, Williams made Hodges’s roster in 1971, serving on the same pitching staff as, among others, Ryan, Tom Seaver, Tug McGraw and Jerry Koosman. It was a bad outing by Kooz that paved the way for Williams’s big league introduction on Friday afternoon, April 23. Jerry was trailing 2-0 in the bottom of the third at Wrigley Field when, with one out, he loaded the bases full of Cubs. Gil had seen enough of his top lefty and sent in his rookie righty.

Charlie grounded his first batter, Original Met Jim Hickman, to first, where Donn Clendenon picked the ball up and threw home for a forceout to Jerry Grote — the backstop who was traded to the Mets in 1965 for Tom Parsons, presumably no relation to Parsons College in Iowa, the university from whence Williams was chosen by the Mets with the first pick in the seventh round of the 1968 draft. He grounded out his second batter, too, getting Hal Breeden to roll to Tim Foli at second. Foli stepped on the bag, 4-unassisted, and Williams had gotten through his first two-thirds of an inning as a Met.

Before his major league debut was over, Charlie Williams would give Gil Hodges a one-run fourth and a scoreless fifth. By the sixth, he was pitching with a 5-3 lead, thanks primarily to Ken Singleton’s two-run homer and a couple of run-scoring singles from Grote. Breeden, however, led off the Cub sixth by taking Charlie deep and Johnny Callison soon pinch-doubled in the tying and go-ahead runs. Williams left on the losing end of the score, 6-5. Ron Taylor came on and cleaned up for him as Charlie had cleaned up for Koosman. The Mets tied the game in the seventh and won it, 7-6, in the twelfth when Singleton knocked in Tommie Agee. Ryan, pitching two shutout innings behind McGraw’s four, earned the decision. But Charlie Williams could also be judged a winner. He was now fully part of the team in whose geographic sphere of influence he grew up.

Charlie would relieve 22 times and start nine games in 1971. There were some standout performances sprinkled among those 31 appearances: 9 K’s versus the Giants on June 11; his first home victory, 7-2 over the Dodgers, on June 16, achieved with a little neighborly help from recently recalled Francis Lewis High alum Mike Jorgensen’s two solo homers; a 3-2 win that came up one out shy of a complete game against the world champion-to-be Pirates on June 22; the opener of the August 3 doubleheader against the Big Red Machine when Charlie went all the way at Shea, scattering eight hits and prevailing, 9-4; and Williams’s final win of the year, at Pittsburgh, noteworthy for two reasons: 1) it prevented the Buccos from clinching their second consecutive N.L. East crown against the Mets; and 2) it was done with the last all-homegrown starting lineup the Mets would field for another 40 years, though Charlie earned the W in relief.

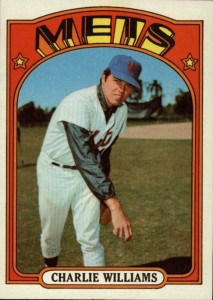

His first full season in the majors, the year Flushing native Charlie Williams came home to pitch, wound up 5-6, with 53 strikeouts in 90.1 innings, and an ERA of 4.78. It had its moments, but it wasn’t enough to guarantee him a spot on the pitching-laden 1972 Mets — even though Topps had certified him otherwise with their No. 388 card during the spring — so he was farmed out to Tidewater.

It was while hurling for the Tides that the from kid from Queens learned what his calling card was going to be for the for the rest of his life.

By dint of birth, native habitat and unfolding circumstance, Charlie Williams seemed destined to pitch for the Mets. Technically, his destiny was fulfilled 31 times over. But that debut against the Cubs, the complete game against the Reds, any of those five wins for the 1971 Mets…that’s not what Charlie Williams would be remembered for. From May 11, 1972, forward, until this past Tuesday — the day he died at the age of 67 following heart surgery that was too much to take atop an array of reported vexing health issues — he lived as one easily digestible line to baseball fans who remained or became aware of him:

Charlie Williams was the player traded for Willie Mays.

With the stunning announcement that Willie was about to, in a sense, do what Charlie had already done — come home to where it all started — Williams was transformed into an instant trivia question. He was now and would forever be in league with the likes of Denehy and Rose and Moore, his Memphis moundmates who, however well they might have pitched at the highest level of baseball in a given game, were remembered because they were parts of trades involving men who had bigger names or accomplished greater things.

In Williams’s case, he was the only player the Mets exchanged for Mays, yet he was essentially the throw-in. From the Candlestick Park perspective, this deal that was struck a month prior to the Watergate break-in was best understood by following the money. Giants owner Horace Stoneham needed the $50,000 Mets owner Joan Payson gladly sent him in exchange for the privilege of dressing her and everybody’s favorite old-time New York Giant in a New York Mets uniform. She’d happily take on the top-of-the-line salary he was due (the prorated portion of $165,000 for 1972 plus $175,000 agreed to for 1973) and guarantee him a post-playing coach’s sinecure as well, a gig Willie kept through the end of the 1970s.

Stoneham would say he never actually accepted the $50,000, he just wanted what was best for Willie. His team did, however, take receipt of Williams, who gave the Giants what could best be described as a serviceable seven seasons. There were a few years in the mid-’70s when advanced metrics are retroactively kind to Charlie, with ERA+ rates topping 100 from 1974 to 1976. His lifetime won-lost mark was 23-22, 18-16 as a Giant. He was a better than .500 pitcher during a period when San Francisco produced mostly losing ballclubs.

In retirement, Charlie moved to the east coast of Florida, where apparently he never shied away from his claim to redirected fame. According to one of his golfing companions, he didn’t have a problem not being known as Charlie Williams the pitcher who reached the top with his hometown team or Charlie Williams who possessed a winning lifetime record or Charlie Williams who won 23 more games in the major leagues than mere mortals. He was fine being Charlie Williams who was known for being what Charlie Williams was automatically known for being…not that he didn’t put a little spin on his own pitch, mind you. As friend Harold Glover related to the Daytona Beach News-Journal, “He’d actually tell everybody that Willie Mays was traded for him.”

However you slice it, there are worse things to be known for.

When you said he went to a college with the same name etc…I thought you meant he went to Parsons School of Design, which would be like the Jets drafting a quarterback out of Juilliard. Then again…

I thought Williams was going to develop into a pretty good pitcher, but he really did wind up as you said, the answer to a trivia question. But he held a singularly unique spot in Mets history, RIP.

The Parsons School of Design has a very good-looking team this year, though FIT always gives them trouble.

Boy this post shows how relatively late I was to the party with following this team. The only Charlie WIlliams I ever knew of in baseball was the umpire of that same name, and his connection to the Mets was an infamous run-in with Cookie Rojas during Game 4 of the 1999 NLDS which got Cookie suspended for all but one game of the NLCS that year. The other Charlie Williams quietly retired in 2002 and died several years ago. So I admit to doing a double-take when I saw this headline.

You had a nice RIP on Ernie Banks, followed by the Willie Mays in town post. Thought your follow-up would be about Hank Aaron to complete the holy trinity of great NL players from the 50s through early 70s.

It’s never too late to get caught up on your Charlie Williamses. (May he rest in peace, but the other Charlie Williams was not a good umpire…though Cookie Rojas was in the wrong on that call.)

A little Aaron from last spring so you don’t go away disappointed.