Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

When Willie Mays returned to New York, many saw it — may God forgive them — as a trade to be debated on the merits of statistics. Could the forty-one-year-old center fielder with ascending temperament and waning batting average help the Mets? To those of us who spent our boyhood, our teens, and our beer-swilling days debating who was the first person of the Holy Trinity — Mantle, Snider, or Mays? — it was a lover’s reprieve from limbo. No matter how Amazin’ the Mets were, a part of our hearts was in San Francisco.

—Joe Flaherty, “Love Song to Willie Mays,” 1972

Maybe it was when I opened to the baseball chapter of the New York Times-branded book of sports records I was given for a seventh birthday present, examined the all-time home run list, and realized the player listed as second was still playing. Maybe it was the cumulative effect of hearing repeated endorsements by announcers — ours as well as the ones who spoke glowingly of him on national telecasts. I could’ve picked it up in the papers during my early, precocious infatuation with sports sections. However the notion embedded itself within my head and heart, by the time the first All-Star Game I tuned into rolled around on July 14, 1970, there was no doubt in my mind.

Willie Mays was the best player in baseball. Maybe not the best at the moment (Johnny Bench seemed to have that title well in hand). Maybe not the best ever (Babe Ruth did have the most home runs). But, nearly twenty years before Tina Turner would make bank off the phrase, and three years before his emotional 1973 retirement choked up the portion of the nation whose pastime would always be baseball, Willie Mays reigned as simply the best. It’s no surprise that leading off in that All-Star Game for the best of leagues, the National, was simply the best player there was.

Of course Willie Mays came first.

Thanks to NBC, I was exposed to a passel of future Hall of Famers that Tuesday night. Twenty players introduced at brand new Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati fifty summers ago now have plaques in Cooperstown. I lapped up all those gallons of greatness swirling through the portable Sony black & white set stationed in my sister’s room that she rarely watched. At seven years old, my July nights were already about baseball. My days, too. The names — Aaron, Clemente, two Robinsons, Seaver obviously, Bench and Perez from the home team, Carew, McCovey, Palmer and on and on — were already familiar to me. I’d seen them everywhere I’d looked. Baseball cards. Baseball lists. Baseball stories. Now they were all together in one baseball place.

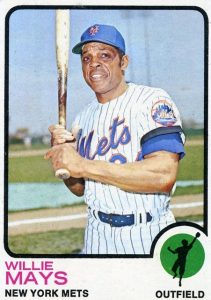

But first and foremost among them was Willie Mays, center fielder for the San Francisco Giants with now more than 600 home runs and the irresistible nickname the Say Hey Kid. He was the best, and as the best, I really wanted his card. Couldn’t get one in 1970, not even in that “Super Series” where the cards were absurdly oversized and incredibly thick. Couldn’t get one in 1971, either. Come 1972, however, my interminable dry spell came to an end (interminable being a relative matter when you’re nine and you’ve been wanting something since you were seven). The very first pack of spring in third grade, purchased at the Cozy Nook on the walk home from East School, revealed his name in a serif font above his smiling face which was framed under a yellow banner from which his team name fairly exploded: GIANTS. I couldn’t believe I had Willie Mays in my hand. I sat in the kitchen, cradled it, marveled at my fortune, and smiled at his smile.

Then I flipped him over. Even at nine…even at seven, I was always more taken by words, numbers and facts than I was images.

Will ya look at that set of statistics? They start in 1950 in the minors (those don’t really count). A year later, he’s in the majors, where he’s stayed ever since. There’s one year that’s blank when he’s “In Military Service,” but otherwise Willie Mays is always playing and always posting titanic totals. As many as 52 homers in one year. As many as 127 RBIs. Batting averages regularly over .300. Those are the main numbers if you’re a baseball fan of any vintage, though the Topps people are kind enough to list ancillary stats like runs and hits and doubles and triples and believe you me (whatever that means; it’s something people said on TV), Willie Mays has a ton of those, too. The yearly accumulations grew a little lighter as the 1960s were ending and the 1970s were beginning, but that, I infer in the spring of 1972, is to be expected. Willie Mays’s birthdate is listed as 5-6-31, which makes him 40 going on 41. He’s almost as old as my father. Eighteen home runs, sixty-one runs batted in and a .271 average — his totals from 1971 — are pretty good for someone over forty. In 1971, Willie Mays helped lead the Giants to a division title. In 1971, Willie Mays had more home runs and more RBIs than anybody on the Mets.

Funny thing about the back of the 1972 Willie Mays card, No. 49 in the first series from Topps (No. 50 was Willie Mays In Action). Where they list “TEAM” and “LEA” for his first bunch of years in the big leagues, Mays isn’t with San Francisco, which is where I know him from. Instead, from 1951 through 1957, including his military service year of 1953, the card says he played for “New York N.L.” I do a double-take. At the age of nine, I know better than to think there was some sort of secret Willie Mays past nobody’s mentioned regarding a long-ago tenure with the only “New York N.L.” I’ve ever experienced. I know my New York Mets of the National League have, like me, been around only since 1962.

I also know, albeit vaguely, that the San Francisco Giants used to be the New York Giants, the way the Los Angeles Dodgers used to be the Brooklyn Dodgers. It doesn’t come up very often in conversation, but it’s one of those myriad ancient, as in before I was born, baseball lessons I’ve absorbed since entering the game’s thrall as a lad of six. I’m nine now. I’ve been around. I pay attention on Old-Timers Day, I’ll have you know. I even remember getting Hoyt Wilhelm’s card in 1970 (it said he was on the Braves but his cap was disturbingly blank), and on the back he got the “New York N.L.” treatment. It was hard to fathom that anybody who played in the 1950s was still playing baseball in the 1970s, but at least a few of those guys were. A couple played for “New York N.L.” before it meant what I know it means now.

Yet here in the spring of 1972, when one has achieved what may have been his first longstanding lifetime goal, a person can dream. I’m looking at this Willie Mays card I finally have. I’m looking at these credentials of his. I’m looking at “New York N.L.” and how it’s attached to him despite the orange SF insignia on his black cap in his picture on the front, the cap the announcers like to mention flies off his head a lot when he’s running. The theoretical juxtaposition lingers for a moment. Willie Mays. New York. Mets.

Then, within two months, the punctuation changes. Willie Mays, New York Mets.

Willie Mays, New York Mets!

The mind boggled. It remains boggled. I’ve since lived numerous times through the happy shock of learning that big Met trades had been made and that big names were suddenly Met names: George Foster; Keith Hernandez; Gary Carter; Mike Piazza; Roberto Alomar; Johan Santana; Yoenis Cespedes. And regardless of the for-better-or-for-worse impact that rippled out of those respective big frigging deals, nothing — nothing — measures up in my formerly nine-year-old mind to learning that Willie Mays was suddenly of the New York Mets.

Willie Mays, New York Mets!

There was a backstory that made sense as to how and why this could have happened and had to happen, and it was connected to the lines below Trenton and Minneapolis and above San Francisco on 1972 Topps Card No. 49. “New York N.L.” wasn’t just dusty ledgerkeeping. “New York N.L.” was where Willie Mays became Willie Mays. It was about more than a Rookie of the Year award in 1951 or an MVP in 1954. It was about an impression made and an impression left and a heart that couldn’t be transported lock, stock and barrel to San Francisco. Willie Mays hadn’t been a home team player in New York for fifteen years, but when the orange NY, which was now embroidered onto royal blue caps, was provided for him anew, he put it on and it fit perfectly. The trade became official as of May 11, 1972: pitcher Charlie Williams and cash that Horace Stoneham needed, for Willie Mays and a return to the loving arms of Joan Payson and the city that never forgot him. Jim Beauchamp, acquired from St. Louis in the offseason for Art Shamsky, graciously gave up the 24 he’d inherited from Art and handed it over to Willie, because Willie Mays, 24 for the New York Giants, was now going to be 24 for the New York Mets.

The mind boggled some more.

Willie Mays, you likely know, played in his first game as a Met versus the Giants, at Shea Stadium on Mother’s Day, in the Mets’ 24th game of the year. You’d think that would be too much symbolism for one ballgame to hold. In the bottom of the first inning, Willie, starting as first baseman rather than center fielder in deference to his being 41, led off the Sunday affair of May 14 by walking and then scoring on Rusty Staub’s grand slam in the first (getting Rusty Staub from the Expos in April was also pretty mind-boggling). In the fifth, with the score tied at four, Willie led off again. This time he homered for the 647th time in his career. The heavens wept. Technically, it was a little rainy, but c’mon. You didn’t need to go back to 1951 with Willie Mays and the New York Giants to understand that this was transcendent. You didn’t need to know the word “transcendent,” even. You could be nine, a fan since you were six, and soak in the wonder of it all. This was a Foxwoods commercial before there was a Foxwoods.

Willie’s homer won the Mets that game over the Giants, and Willie’s play continued to help the Mets win for weeks to come. They were the best team in baseball with the best baseball player there was, and all it took to get him was a Quadruple-A pitcher, Mrs. Payson’s discretionary funds and unabashed sentimentality. The Mets reeled off eleven wins in a row at one point and were 30-11 as June dawned. Willie reached base in the first twenty games in which he came to the plate. Baseball cards didn’t include on-base percentage in 1972, but had Topps had the capability and foresight to rush a modern rendition out to reflect the first not quite seven weeks of Willie Mays’s second “New York N.L.” tenure, it would have noted his OBP between May 14 and June 27 was .463 and his OPS was .914.

Better from my perspective than a new Willie Mays card was the gander I got at the May 26 issue of Life magazine. It, like me, was sitting in the waiting room of my sister’s orthodontist, a fellow soon to become my orthodontist, lucky me. I’d be bracing myself for life with braces long after Life ceased weekly publication. George Wallace was on the cover. Him I wasn’t too concerned with. Inside, on pages 38 and 39, was a spread that made me say, in so many words, “HEY!” It contained — along with an appropriate headline (“Willie Forever!”); a brief explanation of Mays’s May 14 exploits; and a picture of the Mets first baseman’s glorious swing off Giants reliever Don Carrithers as San Francisco catcher Fran Healy watches helplessly — a reproduction of every Willie Mays Topps baseball card from 1952 through 1972. There was the one I got in that first pack. And there were the 1971 and 1970 ones I opened pack after pack in unanswered hopes of getting. And there were what Willie Mays cards looked like in the years before, not just the years from when I’d had cards, but back to the early ’60s and the ’50s, which was the first time I’d ever seen what a baseball card manufactured prior to 1966 looked like.

Most breathtakingly, there was Willie Mays wearing a black cap with an orange NY over and over, representing the New York Giants, which floored me. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen that cap, but it was the first time it truly hit me what this homecoming was all about — and from whence the Mets sprung in terms of lineage. I knew we were an expansion team. I knew something about Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants. But here, in living color, was current New York Met Willie Mays — the best of baseball players — being then-current New York Giant Willie Mays. This array of baseball cards said a million words.

It was then and there that I pledged retroactive fealty to the New York Giants and their orange NY. And it was then and there that I became intractable in my belief that there was nowhere Willie Mays was supposed to be in 1972 and 1973 other than in a uniform that allowed to him to finish his career wearing that orange NY.

Mays didn’t keep up his blistering on-base pace and the Mets didn’t keep up theirs in the winning percentage column. Staub got hurt. Everybody got hurt. The Mets fell from first to a not especially compelling third. Willie was a legend who apparently required a bit of care and feeding regular players didn’t rate. Yogi Berra, the legend who never sought to manage the Mets but had the job thrust on him after the death of Gil Hodges, was put in an awkward position of calculating when he could play him and when he could sit him. After the initial burst of euphoria, Willie Mays in his superstar emeritus phase and the Mets just trying to finish the season didn’t necessarily constitute an ideal marriage.

I didn’t grasp any of that at age nine. I spent the rest of 1972 in a haze of ecstasy that Willie Mays the New York Giant was a New York Met who had hit a home run to win a game versus the San Francisco Giants and that he was — past tense notwithstanding — the best player in baseball. It didn’t matter to me that Hank Aaron passed him on the all-time home run list. I rooted for Aaron to catch Ruth. I liked Aaron from a distance, but there wasn’t nothing particularly New York about him. Mays, as Life made clear, was meant to be ours. Mays was meant to be on my team. Mays was meant to be a Met. It wasn’t that he was the best. It was that he was the best here, for us — for the version of us that preceded us. That orange NY spoke volumes to me.

So he’d stay into 1973 when, save for the occasional reminder of what had made him famous more than twenty years before, he played like a 42-year-old. He was still Willie Mays. He was still named to the All-Star team because he was Willie Mays. He still drew ovations at Shea because he was Willie Mays. He didn’t play like the Willie Mays everybody who’d seen him in 1951 and 1954 swore by. He didn’t play like the Willie Mays I saw for myself in May and June of 1972. He was said to be about as done as the last-place Mets were in the summer of 1973.

But I wouldn’t have traded those two years of Willie Mays for anything or anybody. I wouldn’t have traded him for Hank Aaron, Johnny Bench or any of the in-their-prime future Hall of Famers from the All-Star Game three years earlier. I wouldn’t have asked to have Charlie Williams back had Charlie Williams gone to California and turned into Nolan Ryan rather than remaining Charlie Williams. I had Willie Mays as a New York Met when I was nine and ten. Maybe Willie was too old to play like he did when he was a kid, but I was old enough to get why it didn’t matter. I got the New York Giants connection. I got the meaning behind the ovations. I got why baseball made people not just happy but weepy. It all came together on the night of September 25, when Willie Mays and his 660 home runs — same number Topps would put into its base set of cards over the next few years — said “goodbye to America” in a New York Mets uniform at a packed Shea Stadium. The Mets had improbably scratched and clawed their way into first place. Willie, who’d been hurting and sitting the previous few weeks, gave them his blessing. You gotta believe you me that they won the division and, with Willie pinch-hitting at a critical juncture in Game Five of the playoffs versus the Reds, the pennant.

Perfect ending…except there was that little matter of the Say Hey Kid being pressed into center field action in the literal glare of the Oakland Coliseum in the second game of the World Series and the image of old man Mays being overmatched by fly balls and gravity. By not being as ageless as he had to be (in a game that, oh by the way, the Mets would win in extras on Willie’s RBI single), the best player in baseball became a metaphor for athletes who hang on too long, and Willie Mays’s presence in a Mets uniform would embody something that it was generally decided never looked right. “Mets legend Willie Mays” is supposed to be a guaranteed chuckle-generator on social media, as if coming home to play before appreciative fans who never forgot you somehow factors out to a net negative. Even the stupendous Joe Posnanski, in recently declaring Willie Mays the No. 1 baseball player who’s ever lived — better than Ruth, better than everybody — fell down the well of Willie falling down in center.

Tom Seaver, you may recall, tried to make a comeback with the Mets in June of 1987. The pitching staff was riddled by injuries and Tom was sitting home in Greenwich without a contract. He was 42, but had been solid enough for the Red Sox when he was 41 and, technically, he had never retired. Apparently, though, 41 was the upper limit for 41, because Tom’s comeback attempt lasted only a few weeks and never resulted in his actually coming back. After Barry Lyons roughed him up in a simulated game, Tom definitively announced his retirement at a press conference, admitting his fabled right arm contained no more competitive pitches.

But what if Tom had hung in there a little longer and convinced himself as well as Frank Cashen and Davey Johnson that he had something left? The Mets were sorting through Don Schulze and John Mitchell and whoever that summer. It’s not inconceivable that Tom Seaver could have reached down a little deeper and given the Mets the quality innings they needed to bridge the gap from June to October. So let’s say that happened. Let’s say Tom Seaver helps pitch the Mets to the 1987 division title, then the 1987 National League pennant and, finally, the 1987 World Series. And then, because this is all hypothetical, let’s say Tom Seaver takes the mound at the Metrodome and, figuratively if not literally, falls down on baseball’s biggest stage and that’s how his career ends, forty-two-year-old Tom Seaver, who didn’t know when to quit, implodes with everybody watching.

Someone like me, an adult with precious memories of robust Tom Terrific, might have cringed and wished he’d just stayed in Connecticut looking at proposals for wineries, just as those who went back to the Polo Grounds with their childhood hero didn’t want to see the old Willie Mays of 1973 besmirch the memory of young Willie Mays from 1954. I just now, in 2020, had to invent a hypothetical to get there, but I acknowledge the “Willie falling down in center” trope wasn’t invented in hindsight; there were people who loved Willie Mays who couldn’t bear to see Willie Mays be several levels short of Willie Mays; who couldn’t stand that something as ostensibly sweet as sunshine might get the best of the Say Hey Kid. Yet give me this: had that Seaver scenario played out, there would have been a kid of nine or maybe ten who read stories and saw pictures from 1969 and legitimately tingled from seeing Tom Seaver pitch for the 1987 Mets…and that kid would never forget it. That for that kid, even if Tom Seaver was 42 and no longer fully 41, the Franchise was the Franchise and he belonged on a mound for Mets for as long as he could toe its rubber.

It’s not a perfect analogy, just as Willie Mays’s time as a Met wasn’t without flaws. But to me, it was perfect. To me, Willie Mays is a New York Met. To me, no other Met should wear 24. I could dive into a grubby argument about what represents a retirable number, one of those chintzy debates that inevitably diminishes everybody whose number is namechecked, but I prefer to lean on what Joe Flaherty, an old Giant fan who had converted to the Mets while waiting for his baseball heartthrob to come home, had to say in the Village Voice in 1972.

“Willie, like Scott Fitzgerald’s rich,” Flaherty wrote, “is very different from you and me.”

He was very different from every player. He started with one “New York N.L.” He ended with the other “New York N.L.” And, in between, he was better than every player.

One more number to consider before saying “hey” to 24: 89, as in happy 89th birthday to Willie Mays. That comes tomorrow (5-6-20), another candle atop all of his incandescent yesterdays. I am honored that I was able to witness a few of them where I did when I did.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1994: Rico Brogna

I remember the thrill of pulling him out of packs..And the thrill of seeing him hit that homer in his first game as a Met..That farewell night at Shea in 73 was not to be missed. Topps gave him a complete run of his cards framed!..I was always was in awe of his career and legend..And as you know Greg my son shares a birthday with him tomorrow May 6th..

Your the best be safe..

Thanks Rich — and happy familial birthday!

Im a little younger, born in 65, but I remember it JUST like you said! Willie was my guy too and always will be. Happy birthday to him (tomorrow)

Fantastic as always. How well I remember that Mother’s Day game. How well I remember – and loved – Willie. So he fell down? Big deal! He was Willie Mays! He was ours!

And I assume you remember his 52nd birthday as well…

Thank you — and stay tuned.

My Dad never forced baseball fandom on me, but when I did become one at the age of about 9, the one thing he wanted more than anything was for me to know all about Willie Mays. Like most folks from Jersey City, he was a Giants fan (my one non-Mets piece of baseball apparel is my Jersey City Giants t-shirt), and the 2nd game he took me to, in 1970, was one he picked carefully. It was against the Giants, because he wanted me to see the man he called “the greatest athlete I ever saw.” LOL, he was disappointed when he took a look at the lineup and saw that Willie was playing 1B that day.

My Dad wasn’t a very emotional sports fan, but I still remember the ear-to-ear grin when Willie became a Met. I’m not sure that the Mets should have given #24 any special treatment, because to be perfectly honest, he was a Met the same way Joe Namath was a Ram. But that said, I still spent all of the 2019 season doing a double take every time I saw Robinson Cano wearing it, 20 years after doing the same with Rickey Henderson (let’s forget the Kelvin Torve incident).

Never saw him in his amazing prime, but I’m glad he was on our side for a little while.

I was recently watching a first-season (1977-78) Lou Grant episode in which reporter Joe Rossi, for the staff’s touch football game, was wearing a decidedly non-regulation blue and yellow No. 12 jersey, a clear nod by the Los Angeles-set show to the local QB of the moment. At that moment in time, Namath was a Ram, Frazier a Cav, Erving a Sixer, Seaver getting portrayed by Warhol as a Red.

At least the rest of the country had good taste.

I have to confess, despite my core belief about 24, I’ve gotten somewhat used to seeing Cano borrow it. Future Hall of Famer-ish exception…I’ll allow it…grudgingly.

The perfect storm…..Tom Seaver and Willie Mays, the greatest Met and the greatest player to ever play the game on the greatest team at the same time. Thanks to Dairy Lea milk coupons and the negligence of the MTA, we saw dozens of games during Willie’s last years including Willie scoring the winning run in an extra inning game against Ollie Brown and the Padres. Magic.

Both of those giants were at the last game at Shea which will soon be twelve years ago.

Seaver Way and soon a statue…….retire 24! Thanks Greg and Jason.

Maybe it’s a sign of the times, but the mention of Ollie Brown gave me chills. Those other fellas, too.

The thing with Tom Seaver is though that he almost was that guy that came home and hung around too long. He was on the ’86 Red Sox after all, and if the Mets are a little less protective of Ron Gardenhire of all people after ’83, then he might conceivably been out hurt as an ’86 Met during the World Series.

As things actually happened, he got nothing. No ring, and no action during the World Series. Not that I’m mad about the first item there.

Great memories, Greg. You and I are the same age and I remember the Mother’s Day game because my dad and I were listening to it on the radio from rural Connecticut as we cleaned out the garage (a Mother’s Day ritual). Like you I was a Mets fan AND a Mays fan. The first time I saw him at Shea was in 1971 (we had moved to Connecticut from Rhode Island the year before). I can still remember holding my Dad’s Korean War binoculars (my Dad, who died in 1992, was a little younger than Willie) and finding him outside the Giants dugout and catching him laughing, gleaming. He started and played CF.

As some point the Mets fell behind (truth be told there were no Mays heroics that day — I think he went 1 for 4 with a single) and most in my section launched a “Let’s Go Mets! Let’s Go Mets!” chant and an African-American woman sitting right in front of me, turned and looked me right in the eye and asked, “Don’t you like Willie Mays?” I was stunned. Of course I did! And I wanted her to know that I could root for the Mets and root for Willie but I was tongue-tied and she turned back around to watch the game.

Years later it occurred to me that perhaps for her — a woman in her late thirties or early forties (I can still see her face, good-natured in its indictment of my loyalties) had been, in 1958, a young woman in her late teens or, at most, early 20s when Willie and the Giants left the Polo Grounds for the West Coast. As I am now in my late 50s (as are you, Greg), I can see how quickly those mere thirteen years had flown by for her. I sit now and type this and imagine how ecstatic she must have been when Willie — just a year later — was returned to New York.

The ’72 card was in the first series of the first set I had committed to completing. I had dabbled in ’70 and ’71 but, like you, I didn’t get a Mays card. I remember I opened up a pack of cards in the car as my Mom drove me Little League practice and when I got home that night the Sports Illustrated with Mays on the cover was on the coffee table in the living room.

I was the first kid in my neighborhood to acquire the Mays card in 1973, with his face looking decidedly older (his forearms and famously large hands look ready to hit nonetheless) on the first (but not the last) Topps card with Mays in a Mets uniform. The next season — 1974 — I was thrilled to find a World Series card that featured Mays. We watched that World Series in 1973 with more excitement and anticipation than any other sporting event. I hated the Oakland team (not clear now why, maybe something to do with Charlie Finley, the owner). The run to the playoffs (including Willie’s farewell celebration) had been exhausting and the Rose/Harrelson fight had been followed by ugliness from the left field upper deck. Do you remember Mays, Staub, Seaver, and Berra (maybe there was a fifth Met in uniform but whoever it was escapes me now) walked out to left to plead with the Mets faithful not to throw batteries or Johnny Walker bottles at Pete Rose or the Mets would have to forfeit.

Happy Birthday, Willie. And thanks to you Greg for your memories.

Great stream of memories there, Jay. Thanks for sharing.

Willie’s Met career was a little before my time as a fan, but I get the sentiment. I remember how I felt when the Mets regained Tom Seaver in ’83 – he wasn’t what he had been, but hey, who cared? He was Tom Seaver, and he was back where he belonged – at least temporarily.

And speaking of Seaver’s ’87 comeback attempt, I sometimes think of the dystopian version – what if Seaver wasn’t injured in ’86, and wound up being the starting pitcher against the Mets in Game 7? Win or lose, that would have shaken up an already fraught storyline.

I love this series, by the way. Keep it coming, guys, and stay healthy.

I trembled with hesitation at the prospective Seaver vs Mets matchup as 1986 moved along. A bad knee took care of those overtones, but, oh man, how crazy that would’ve been.

Thanks for reading!

[…] Mets Legend Willie Mays » […]