When Joey Lucchesi, acquired from the Padres on January 19, Inauguration Eve, makes his first appearance as a Met, he will become the first Met to go by Joey. That’s a legitimate choice. Just ask Joey Votto, Joey Bishop or David Geddes, who took “Run Joey Run” to No. 4 in 1975. Just ask Joe Biden, whose folks, per the 46th president’s recurring recollections, tended to address their eldest son as Joey. Biden took “Run Joey Run” to heart, running for office so long and so often he was elected president after the most recent of those runs. Let that be a lesson for all you kids out there.

Pending acting GM Zack Scott’s tinkering, Joey Lucchesi enters 2021 with a solid chance to be No. 5 in his new club’s rotation. And on the day a fifth starter pitches, he might as well be No. 1. Yet eighteen Mets before Joseph George Lucchesi decided to go with Joe. Just Joe. Simple in its elegance. Elegant in its simplicity. And since January 20, Inauguration Day, unimpeachably presidential. Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr., you might have heard, is our first of 46 chief executives to go by Joe.

Joe Biden wearing No. 46 at a Congressional baseball game proved prescient. The Phillies part is a symptom of where he’s from.

With Presidents Day weekend in progress, our Metsian instinct is to tip our caps to the likes of Claudell Washington, Gary Carter, Stanley Jefferson, several Jacksons and a few other Mets who share presidential last names. This February, however, we decided to go in a different direction. Thus, while we’re (ahem) bidin’ our time ahead of Spring Training, settle in for some nonpartisan fun with a few Met presidential first names of note.

We — the USA — started with a George as president, Mr. Washington in 1789. The other we — the Mets — had our first George in 1964: outfielder George Altman, a certified One-Year Wonder at Shea. He’d twice been an All-Star for the Cubs, who traded him to the Cardinals, who traded him to the Mets (with Bill Wakefield for Roger Craig). After batting .230 with nine homers, the Mets circled him back to the North Side of Chicago (for Billy Cowan). The Father of Our Georges would give way to three other Met Georges: George Stone, George Theodore and George Foster. Four others if you count George Thomas Seaver…and why wouldn’t you?

The Mets came to be under the presidency of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, popularly referred to, as Johns will be, as Jack. The first Met Jack came along the same season as the first Met George: Jack Fisher, who threw the very first pitch at Shea Stadium, April 17, 1964, with Altman around in right. Like JFK, Jack Fisher was born a John: John Howard Fisher. I don’t recall his being referred to as JHF, though he did pitch at a jauntily high frequency, starting 133 games between 1964 and 1967. Jack Fisher set the record for most starts in a single season by a Mets pitcher, with 36 in 1965. His mark has been matched since only by GTS.

The subsequent Jacks dealt onto Mets rosters were, in chronological order, Hamilton, Lamabe, DiLauro, Aker, Heidemann, Egbert, Leathersich and Reinheimer. I find it curious that three dozen years passed Heidemann’s last Met game in 1976 and Egbert’s sole Mets game in 2012. Among them, however, the Jacks of relatively contemporary vintage — relievers Egbert and Leathersich and utilityman Reinheimer — didn’t start as many games for the Mets as Fisher started in his least busy campaign.

Jacks may breeze into and flit out of style, but our Met Joes have always known how to spread themselves out. From the 1960s to the 2010s, there’s been at least one Joe to play for the Mets in each decade. Why, we began 1962 with a Joe among the Original Mets, Joe Ginsberg. The veteran catcher earned a spot on the Mets’ first active roster, which enabled him to become the very first ex-Met. His last game, for us or anybody, was our fourth as a franchise.

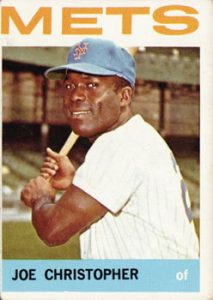

Easy come, easy Joe. The Mets had another Joe almost from the word go, Joe Christopher. His 1962 may not have been much (.244/.338/.362), but Christopher blossomed as the eventual everyday right fielder and fan favorite in 1964 (.300/.360/.466). Before 1962 was over, the Mets added their third Joe and second so-named catcher, Joe Pignatano. Later generations became intimately familiar with Piggy from his tending relievers and tomatoes as bullpen coach. His most memorable Met at-bat was the last of his career, a 4-6-3 triple play in the 120th loss of that first Joe-laden year.

The Sixties would give us six Joes in all, with Joe Hicks, Joe Grzenda and Joe Moock rounding out the sextet. The Seventies dawned with the third baseman projected to slam shut the Mets’ infamous hot corner revolving door, Joe Foy. Ah, but did you ever try to slam a revolving door? Foy, like Hicks, Grzenda —à la Biden, a Joe born in Scranton — and Moock, only played in one Met season. His 1970 contained one amazing game: a 5-for-5 explosion at Candlestick Park that encompassed two homers, a double, five ribbies and the tenth-inning dinger that made the Mets victorious. This left 98 other games less shall we say explosive except for the trade that brought him to Shea blowing up in the Mets’ face. Foy was obtained from Kansas City in exchange for Amos Otis, who went to five All-Star Games as a Royal and gathered nearly 2,000 hits for KC across fourteen seasons.

The Mets haven’t tried their luck with either an Amos or an Otis since.

Joe Nolan caught in three games for the Mets in September and October of 1972 and pinch-hit in another. While he wasn’t garnering much support for playing time from Yogi Berra, another Joe was proving more appealing to his intended audience down in Delaware. Joe Biden and Joe Nolan showed up in the big leagues right around the same time. Biden would be elected to the Senate that November. Nolan would spend 1973 and 1974 in the minors before resurfacing with Atlanta and commencing one of those stalwart backup catcher careers that used to seem common, playing in eleven seasons, only once starting more than half of his team’s games. He’d earn a World Series ring with the Orioles in 1983, about the time savvy political types began sizing up Biden, then in his early forties, as potential presidential timber. He considered a run for 1984 before demurring and deciding to stay in the Senate, where he’d soon begin serving a third term.

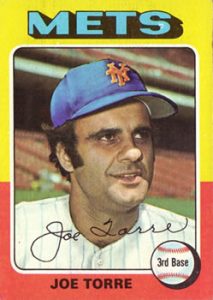

Joe Torre had been in baseball since before there were Mets — he debuted as a Milwaukee Brave in September of 1960, during Joe Biden’s senior year of high school — and would wait forever to get what Joe Nolan earned as an O and what Joe Pignatano received as a coach in 1969. When the former MVP came to the Mets in 1975, a half-dozen revolving door spins since Foy at third base, it was reasonable to imagine the Brooklynite would play a role on a world champion in New York. Indeed he would…but in the Bronx as a manager more than twenty years later.

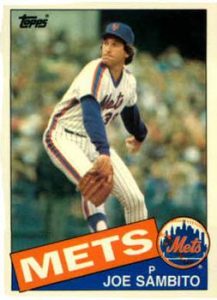

In the mid-1980s, a few years after Torre was asked to stop managing in Flushing, the Mets had grown a lot closer to reaching one of those tantalizing World Series. To perhaps put them over the top, they brought in another local Joe, lefty Joe Sambito. Like Torre, Foy, Pignatano and Ginsberg, he was born within the five boroughs. From 1979 to 1981, he was one of the best closers in the National League, playing a key role in the Astros’ rise to prominence. Then he got hurt, winding up on the Mets for a spell in 1985. His brief tenure is recalled mainly for his having pitched in the infamous 26-7 Mets loss at Veterans Stadium when he gave up eight earned runs in three innings.

Sambito didn’t pitch for the Mets again. Whence next they saw him, it was during the 1986 World Series. Joe was a reliever for the Red Sox. In a third-of-an-inning, he posted an ERA of 27.00. Unlike that night in Philadelphia, Mets fans weren’t complaining.

One (or one who wasn’t Joe Sambito) wishes time could have stood still as the 1986 World Series concluded. But time does what time will do, and time was flying. Joe Biden had run briefly for president in the late 1980s. He chaired the Clarence Thomas hearings in the early 1990s. Neither event went great for him. In 1992, as a different youthful political star born in the 1940s was winning the White House, the first Met born in the 1970s was taking the field, righthanded pitcher Joe Vitko. A native of nearby Somerville, N.J., Joe broke the decade barrier by throwing a scoreless ninth inning versus the Expos at Shea on September 18. He also gave up his first hit to a future Hall of Famer, Larry Walker. Yet there was no reason Vitko, 22 and the only Met Joe to come along while George H.W. Bush was president, couldn’t have dreamed Cooperstown dreams of his own.

Alas, Vitko’s threw his final big league inning on September 28, 1992, five weeks before Bill Clinton, 46, was elected our 43rd president, three months before Joe himself turned 23 years old. So Joe Vitko from New Jersey would be gone from Shea in the season that followed his debut, but Joe Orsulak from New Jersey would arrive. The Parsippany Kid, if you will, proved a valuable lefty bat for a Met club that had little else worthwhile in 1993 and stuck around as the Mets began to refind their footing before and after the 1994-95 strike. My fondness for Joe Orsulak has been duly noted.

(Also worth duly noting: the second Met born in the 1970s was Bobby J. Jones, who had a far longer run than Joe Vitko…and whose middle name is Joseph, and whose middle name can’t be spelled without J-o-e. It’s worth duly noting because Friend of FAFIF Mark Simon just published a splendid SABR Biography of the only Met to throw a post-season one-hitter, a profile you can access here. I really like the part about why Jones strove to remain calm when the cameras were on him.)

I’m mostly agnostic on Joe Crawford, lefty pitcher for the 1997 Mets, but I’m perpetually gaga for the 1997 Mets, so even the slightest of 1997 Met achievements warms my cockles no end. On August 21, Joe took a spot start, opening a twi-night doubleheader by defeating the Dodgers with six innings of three-hit ball. Consider my cockles warmed.

Joeficionados refer to the 2000s as the Joenaissance, starting with the 2000 season. BUT, before we get to the turning point, let us pay homage to a pair of throwbacks, the two most recent Met catchers named Joe.

When he came up as a 29-year-old newbie for two pinch-hitting appearances and two half-innings of catching over two nights in Houston (August 5-6, 2003) before completely disappearing from the MLB radar, you might have confidently said Joe DePastino couldn’t have had a shorter big league or Met career. Yet you would have been wrong. True, DePastino’s stay was brief and hard-earned — he’d been in pro ball without a sniff since before Joe Vitko was a Met more than a decade earlier — but seeing this Joe make it for a minute meant you hadn’t seen all such a story had to offer.

A year later, at the very end of the 2004 season, Art Howe — the same manager who gave DePastino his break — granted a line in a box score to Joe Hietpas. In the top of the ninth inning of Game 162, with the Mets well in front, Howe sent Hietpas into catch Bartolome Fortunato for five batters. Hietpas himself never had the pleasure of standing at the plate at Shea or any other stadium above Triple-A. By 2005, he was in the minors again. By 2006, he was a pitcher. In 2020, he was A Met for All Seasons, if only a player for a moment.

If a discreet gentleman were to choose a nom de plume to write on an HOURLY RATES motel guest register, “Joe Smith” might be the first generic entry to spring to mind. Ah, but Joe Smith, a sidearming righty reliever proved a long-term renter, if not on the Mets, then in the majors. Smith surprised by making the Mets staff out of Spring Training in 2007 at age 23. While six-term senator Joe Biden was planning a second presidential run, Joe Smith was becoming a primary option out of the pen for Willie Randolph, pitching in 54 games as a rookie. A year later, Biden was out of the race for his party’s nomination, but Smith made the Mets’ ballot 82 times. Young and possessing an unorthodox delivery, Joe was that rare Met reliever whose reputation wasn’t destroyed by the general bullpen implosion that helped close down Shea. Come December of ’08, Joe Smith was traded to Cleveland. That was one month after Joe Biden was elected vice president of the United States and one month before Biden took the oath of office alongside Barack Obama

Quite the interregnum for both Joes. Smith would stick around getting outs everywhere through the fall of 2019, when he’d pitch in his first World Series, as an Astro. Five years earlier, another Joe played in the Fall Classic, but as a rookie. Joe Panik, a product of the nearby Hudson Valley, made himself essential to the essential to the even-year San Francisco Giants dynasty of the first half of the 2010s. While Smith was preparing for the final postseason during which nobody’d ever heard of COVID-19, Panik was trying to help the Mets make a late playoff push by becoming the eighteenth Met Joe ever and the only Met Joe of the decade. Panik played well in a limited role, but the Mets didn’t roll into October. In 2020, Joe Panik was a Blue Jay and has signed with Toronto to be one again. During the same pandemic-shortened season, Smith sat out due to family health concerns, but looks forward to returning to pitching for the ’Stros in 2021. As of this cusp-of-Spring Training writing, he is the only Shea Met still signed to a big league contract, though Ollie Perez’s left arm remains eternally available.

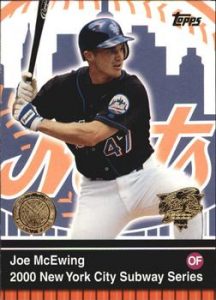

Oh, and Joe Biden is president, a few weeks after his inauguration, having spent his first Presidents Day weekend ensconced at Camp David (named in honor of David Wright, of course) and running the executive branch in the aftermath of the virtual Queens Baseball Convention, whose special online guest was the chronologically fourteenth Joe to play for the Mets, Joe McEwing.

As noted above, McEwing was the Joe to usher in the Met Joenaissance. Upon his trade to the Mets in 2000, you might say he symbolically ushered out the previous century. To get this Joe, the Mets had to give up the only active major leaguer who had been a Met in the 1970s, never mind the only active major leaguer who had literally saved the Mets’ most recent world championship.

On December 10, 1999, the Mets swapped lefty specialists with the Baltimore Orioles, sending Chuck McElroy down Biden’s beloved Amtrak corridor for Orosco. Orosco at that point had been on the MLB scene for some twenty years. He pitched for the Mets when the Mets still had Ed Kranepool, who came up to the Mets before The Jetsons forecasted life in the 21st century. Jesse was going to pitch for the Mets in that very same suddenly arrived future. We wouldn’t have flying cars in the year 2000, but we would have the same lefty who tossed his glove in the air on October 27, 1986, maybe giving us cause to celebrate anew.

Except the Mets traded the dream of Jesse Orosco in the 21st century to St. Louis for bench depth. At the time, I was disappointed from a storyline standpoint. Over the next five years, I’d come to value Joe McEwing’s versatility. No Joe made it into more games as a Met than McEwing. He played in 502 of them from 2000 to 2004. Few Mets played more positions as a Met. Super Joe didn’t pitch and catch. He did everything else. He played every infield position, every outfield position, pinch-hit and — this is the part I love — pinch-ran. I mean he really pinch-ran.

Just as no Joe has played more games as a Met than McEwing, no player has pinch-run as a Met more than the Bristol, Pa., native. Sure, you probably recall him for his turning into a slugger at the sight of Randy Johnson, but did you know how often Super Joe insinuated himself into games for speed’s sake?

I’ll be happy to tell you. Joe McEwing pinch-ran 56 times in regular-season play between 2000 and 2004, topping the longtime previous franchise recordholder, Rod Kanehl by four. Super Joe. Hot Rod. Third place, incidentally, belongs to a pitcher, Little Al Jackson. You can’t say serious pinch-runners defy descriptions. In the postseason, McEwing was doing his thing as well, taking somebody else’s base eight times; no other Met has pinch-run in the playoffs/World Series more than twice.

During baseball’s hiatus last May, the Irish American Baseball Society hosted a Zoom call with Joe McEwing, who would have been coaching White Sox players at that time of year most years. For a few well-worth-it bucks, you could sit in, listen, ask a question, maybe learn something you didn’t know about playing baseball. With no game to watch, I signed up, raised my virtual hand and asked Joe to explain how a player sitting on the bench gets the most out of going into the game to run for somebody else.

That’s what I took a lot of pride in. That started at 12:30 in the afternoon, with my pregame preparation.

If I wasn’t in the lineup. I was preparing mentally and physically for whatever was possibly gonna happen during that game.

Whether it was pinch-running, defensive replacement, pinch-hitting. I was an individual who hated missing outs during a game, but I had to be prepared for every situation, ’cause I never knew when I was gonna be called upon.

It could be the first inning, could be the seventh inning, could be the fifth inning, could be the ninth inning.

So in between innings, as soon as the third out was made, if I wasn’t playing that day, I’d go run sprints in the hallway. And then I would take a few swings off the tee under beautiful Shea Stadium — trying to miss rats that were coming out — then throw a few balls into the net, then head back to the dugout, then watch the next half inning.

Go back up, run sprints, take a couple swings again, just so I was mentally and physically prepared for any situation that was gonna happen during the game.

The thing about it was I observed so much throughout a game that I didn’t want to miss an out, I didn’t want to miss a pitch. Those two-and-a-half, three minutes between, I maximized every second of it.

It’s more mentally and physically exhausting not playing than it is playing.

Followup for Coach McEwing (and not about the rats of Shea): Was it different being a pinch-runner versus getting on base as, shall we say, your own hitter?

That all starts at 12:30. You’re breaking down video of every single guy on the mound: the starter, every guy in the bullpen. His times to the plate. His moves. Does he have quick feet? Is he hard coming over? Does he have any tells? Does he tip when he’s going to the plate? Or with head movements? Or whatever when he’s coming over. And you try to take advantage of every single situation because 90 feet mean a ballgame.

If you’re reading that ball in the dirt, you’re taking that base, now you’re in scoring position. You’re stealing that base, now you’re in scoring position to put your team in a better position to be successful.

As for the challenge of coming in cold rather than having been in the game the entire time, Super Joe explained, “That was my life. That was my career. That was my job. I took extreme pride in that, being prepared for every situation.” The preparation, he concluded, earned him a substantial career in the big leagues.

One could choose to say something similar about another Joe born in Pennsylvania who was (ahem again) bidin’ his time preparing for his next chance and was eventually called on in a pinch to do a job, but I aimed to be nonpartisan with this feature.

Happy Presidents Day, everybody!

What about Joey Bats?

We’re not doing Joses today, but point taken.

I wasn’t aware that Joe Panik was born in Yonkers. He went to John Jay High School in Fishkill, and I think Dutchess County would claim him as their own.

And on the topic of Presidents (President’s? Presidents’?) Day, other than Anthony, Chris, and Eric Jr., what Mets (if any) share the last name of “The President?”

There are bound to be plenty with the same name as “El Presidente,” but I’ll be mighty surprised if any with the last names Ballew, Finn, or Dederer (PUSA).

Geographic revision considered and made.

Appreciated, but Dutchess County is part of the Mid-Hudson Valley. The bridge connecting county seat Poughkeepsie to Highland, before being renamed for FDR, was called the Mid-Hudson Bridge.

I totally forgot there was a second Chris Young. And fewer Martinez than I expected: only five (two Pedros), and not one from Nicaragua. And none of the other guys.

For Joe Moocks everywhere:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CtAl0bXSmzI

Joseph George Lucchesi. Last as President, first as President, fifth in the Mets rotation.

And that’s all I got on the dude, other than him sharing the last name of the guy who took the hit (literally) to get us Lenny Randle. Let’s hope he’s better than last year’s end-of-the-rotation guys. Not a high bar to clear.

As for the current veep, I got nada. If Carmelo Martinez had been a Met, then we’d have something to talk about. Maybe.

Though I did not play for the Mets (or anyone) I resemble (and appreciate) this column.

And a certain high profile catcher of ours middle name would like to have a word with you.

Cowboy up! Nope, still wrong “illar.”

chuck, sounds like the making of a poem, or at least a song parody, “Sung to the Tune of….”

A mea culpa to eric1973 and to the entire FAFIF community: I have been a fan of the “illar” I’ve been referring to for quite some time. I attended a double-A game in Portland, Maine, in, I think, 1997, when he hit two home runs.

Years later, I attended a game in Baltimore, when he played for the Orioles, and he hit two home runs off the Embodiment Of Everything That Is Wrong With This Country And Why The Rest Of The World Hates Us. Actually, in Portland, the two touch-em-alls were off the same organization’s Double-A team.

Thank you, Greg and Jason.

[…] is bringing his Cookie sweetness and inspiration to our cause. Joey Lucceshi is applying his semi-familiar first name to our historical record. Jordan Yamamoto is no longer carrying the scent of a Marlin. […]