For someone who writes plenty in the first-person, there’s nonetheless a phrase I try to avoid: “As I’ve written before…” It strikes me as self-aggrandizing, and to this point in the MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT [1] countdown, I have resisted the temptation to use it or, save for the winking inclusion of a screenshotted headline [2], explicitly refer to anything I’ve previously written on this blog.

But the season we’re about to revisit lives on for me mostly because it was the season I began to write on this blog. In the season when what you’re looking at all started, writing on this blog began to redefine me and my relationship to my team. I would never again consume Mets baseball without thinking of how I would put what I was experiencing into words.

As I’ve written before, the link [3] between me and the Mets reached a whole new level of inextricable that year.

14. 2005

When the 2005 season ended, I thought I was one lucky sumbitch. What a year to construct, alongside a very good friend, a perch from which those two people could share their thoughts daily on what their favorite baseball team was up to. Our baseball team was up to so much!

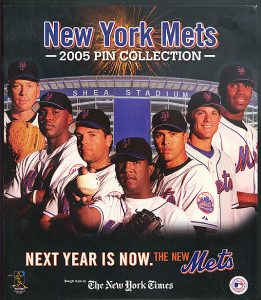

Thinking back on it, had Faith and Fear in Flushing begun in 2003 or 2004 — years the Mets were trying to erase as they set their sights on what amounted to a total 2005 image reboot — there would have been a surfeit of material, too. Same for any season to which a hardcore fan/chronicler chooses to devote himself. It’s the Mets. We care. The story is always yearning to be put into words.

Nevertheless, I still believe 2005 was the perfect season for Jason and me to commence doing what we’ve spent the past nineteen seasons doing. I don’t know how in vogue the phrase “content” was among the media-savvy then, but brother, did 2005 give us content: content that made a fan/chronicler content, and content capable of filling a fan/chronicler with discontent.

[4]Downers in the course of 162 games were inevitable, but as a launching point, a team that finished four games above .500 and vied on the fringes of the Wild Card race until September grew serious manifested itself in everything a first-year blogger could have wanted — and wasn’t too bad for a longtime rooter, either. On its own merits, even if you didn’t commit to writing it up, 2005 was a quality season. Winning more games than you lose is always positive. Winning a whole lot of games is always preferable, but probably not reasonable to expect when you’ve just muddled through the previous two seasons losing 95 and 91, respectively. The 2005 Mets weren’t too hot. The 2005 Mets weren’t too cold. The 83-79 output of Team Just Right (featuring more than just Wright) sufficed. Besides, experiencing high and lows provides a new blog with a bounty of storylines.

[4]Downers in the course of 162 games were inevitable, but as a launching point, a team that finished four games above .500 and vied on the fringes of the Wild Card race until September grew serious manifested itself in everything a first-year blogger could have wanted — and wasn’t too bad for a longtime rooter, either. On its own merits, even if you didn’t commit to writing it up, 2005 was a quality season. Winning more games than you lose is always positive. Winning a whole lot of games is always preferable, but probably not reasonable to expect when you’ve just muddled through the previous two seasons losing 95 and 91, respectively. The 2005 Mets weren’t too hot. The 2005 Mets weren’t too cold. The 83-79 output of Team Just Right (featuring more than just Wright) sufficed. Besides, experiencing high and lows provides a new blog with a bounty of storylines.

Not that there weren’t already storylines galore awaiting us when we turned this thing on on February 16, 2005.

• Ace pitcher Pedro Martinez suddenly and shockingly descending from the stratosphere of superstardom to serve as face of this recently misbegotten franchise.

• Center fielder Carlos Beltran, coming off the postseason performance of a lifetime, and accepting a lucrative offer from a team that rarely proffered lucrative offers.

• The first true full seasons of shortstop Jose Reyes, 21, and third baseman David Wright, 22, avatars of homegrown promise and perhaps harbingers of a day when the likes of Martinez and Beltran wouldn’t have to be convinced too strenuously to join the humble Mets (and maybe we wouldn’t have to rely on glamorous free agents if we could keep growing players like these two kids).

• The approaching Met twilight of 36-year-old icon Mike Piazza, who had one year left on his contract, the wear and tear associated with a career full of catching, and no desire to return to his previous encampment at first base.

• The simultaneous lidlifting on the eras of Willie Randolph — respected New York baseball lifer at last receiving a chance to manage — and Omar Minaya — admired front-office mind tasked to run the whole show in Flushing.

[5]And those were just the storylines spelled out in advance. The season got into gear, and there was Cliff Floyd staying healthy while making pitchers sick; Beltran’s center field predecessor Mike Cameron reluctantly accepting reassignment to right; T#m Gl@v!ne seemingly settling in as an actual Met after two years working undercover as The Manchurian Brave; word that the Mets would soon air their own dedicated cable network; word that ownership and the city would collaborate on building a glittering new ballpark befitting these glittering New Mets (in conjunction with a bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics that were totally coming to NYC); and an onslaught of anxiety applied to a supporting cast whose identities were of paramount importance in 2005, even if hindsight suggests they were simply ballplayers trying to perform to the best of their ability and not necessarily meeting that goal on a sustained basis.

[5]And those were just the storylines spelled out in advance. The season got into gear, and there was Cliff Floyd staying healthy while making pitchers sick; Beltran’s center field predecessor Mike Cameron reluctantly accepting reassignment to right; T#m Gl@v!ne seemingly settling in as an actual Met after two years working undercover as The Manchurian Brave; word that the Mets would soon air their own dedicated cable network; word that ownership and the city would collaborate on building a glittering new ballpark befitting these glittering New Mets (in conjunction with a bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics that were totally coming to NYC); and an onslaught of anxiety applied to a supporting cast whose identities were of paramount importance in 2005, even if hindsight suggests they were simply ballplayers trying to perform to the best of their ability and not necessarily meeting that goal on a sustained basis.

As fans, we responded as we usually did when a starter didn’t last enough innings, or a reliever coughed up a lead, or a borderline veteran was taking at-bats that an unproven rookie could be using to prove himself. As fan/chroniclers, however, it was all new. So, we told ourselves, let’s form and share opinions about people whose names screamed relevance down the corridors of 2005, yet now whisper, “hey, remember how significant my effectiveness and/or production seemed to you when you were writing about me all those years ago?”

Less Miguel Cairo! More Anderson Hernandez!

Less Gerald Williams! More Victor Diaz!

Enough with Doug Mientkiewicz! Permanently install Mike Jacobs!

What the hell’s the deal with Kaz Ishii? Kris Benson? Victor Zambrano?

No, don’t bring in Felix Heredia…or Manny Aybar…or Mike Matthews…or Mike DeJean…or Danny Graves…or Tim Hamulack…or Shingo Takatsu.

WHEN ARE THEY GOING TO GIVE ROYCE RING THE BALL IN THE NINTH?

You can swap out most of those names for Mets who preceded or succeeded them in the middles of rotations or backs of bullpens or ends of benches to fill similar roles with modest results. Some things about 2005 weren’t as altogether eye-opening as they appeared. A gripe or a cause will always come along in the course of a season. I probably understood that innately then.

Yet I wrote as if everything the Mets did and every Met who did it was enormous. Because from my new perch as half of a Web site that endeavored to speak the Mets fan language to those who were fluent, it was. And they were. You had to love and had to obsess on this team, component by component, if you were going to make the most of this perch. It never occurred to me there was another way go about blogging our first season.

Besides, we had some highlights truly worth obsessing over.

Like that time that Aaron Heilman, en route from serving as a failed starter to a somewhat reliable reliever, snapped off a complete game one-hitter against Josh Beckett (when he was a big deal) and the Marlins (not yet having eviscerated their fairly recent world championship credentials). The only hit Aaron surrendered was a fourth-inning infield single to Luis Castillo, a name that doesn’t survive in Met lore as that guy who prevented our first no-hitter, for reasons that would become clear four years and one pop fly hence.

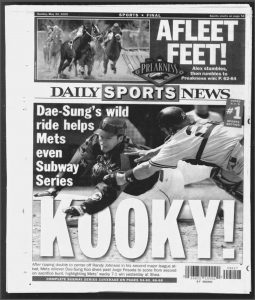

[6]Like that time Dae-Sung Koo, a Korean working in America for this season and this season only, took his literal first swing in the major leagues — he’d struck out with the bat never leaving his shoulder in his only other plate appearance — and not only did it turn into a ringing double off Randy Johnson (when Johnson was mysteriously pitching for the Yankees), but Mr. Koo immediately thereafter came around from second on a bunt from Jose Reyes. Did we mention Mr. Koo, who legally had to be referred to as Mr. Koo, was a pitcher? Never won, lost or saved a game in 33 outings, and never batted again, either.

[6]Like that time Dae-Sung Koo, a Korean working in America for this season and this season only, took his literal first swing in the major leagues — he’d struck out with the bat never leaving his shoulder in his only other plate appearance — and not only did it turn into a ringing double off Randy Johnson (when Johnson was mysteriously pitching for the Yankees), but Mr. Koo immediately thereafter came around from second on a bunt from Jose Reyes. Did we mention Mr. Koo, who legally had to be referred to as Mr. Koo, was a pitcher? Never won, lost or saved a game in 33 outings, and never batted again, either.

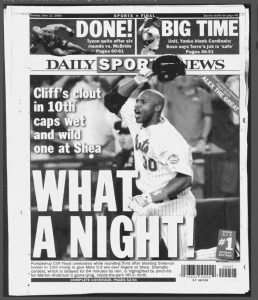

Like that time journeyman Marlon Anderson pinch-hit a ninth-inning, game-tying inside-the-park home run, necessitating the acronym ITPPHHR for the first (and still only) instant in Mets history, finding the time during his 360-foot journey home to blow a bubble while gasping for air.

[7]Like Cliff Floyd winning that very same ITPPHHR game with a more conventional shot over the wall in the bottom of the tenth.

[7]Like Cliff Floyd winning that very same ITPPHHR game with a more conventional shot over the wall in the bottom of the tenth.

Like Victor Zambrano, whom almost nobody trusted, outpitching Carlos Zambrano (no relation in any sense of the word) on Sunday Night Baseball.

Like Steve Trachsel, speaking of uninspiring starters, emerging from the DL in San Francisco to stymie the Giants by a score of 1-0, thanks to David Wright homering, that rare night when it was we who had the young differencemaker in our lineup.

Like preternaturally grizzled Roberto Hernandez stranding two runners and silencing tens and thousands of voluble doubters on a sweltering Shea afternoon when he struck out dangerous Derrek Lee to preserve a shutout started by Jae Seo.

Like Seo, never granted more than a rotation toehold, three months earlier throwing seven one-hit innings while knowing he was going to be sent back to Norfolk ASAP (roster-juggling has always been more art than science in these parts).

Like presumed-obsolete Miguel Cairo delivering a walkoff single as the Mets withstood impending elimination.

Like the great Pedro Martinez utlimately overwhelming an overwhelming John Smoltz on Easter Sunday.

Like the great Mike Piazza taking what amounted to a seven-minute curtain call on the final day of the season.

Like Chris Woodward, usually an infielder, making a dazzling catch in the outfield in a critical eighth inning.

Like Ramon Castro, usually a backup, belting a go-ahead dinger in another critical eighth inning.

Like Mike Cameron, for a time adjusting to right, slipping on grass, sticking out his glove, and snaring a sinking liner.

Like Kaz Ishii holding own versus Roger Clemens the last time Roger Clemens dared show his unpleasant Astro ass on the Shea Stadium mound, a night that proceeded with the starters exchanging seven zeroes apiece and ended with Jose Reyes driving in the game’s only run in the eleventh.

Like the Mets’ first win ever over an entity called the Washington Nationals, an enterprise that bore a modest resemblance to an outfit called the Montreal Expos.

Like the Mets’ first win at the Oakland Coliseum, or whatever corporate name it had that week, since the 1973 World Series.

Like the Mets’ last win the last time they would ever play at what was about to become old Busch Stadium, site of so much mutual snarling in the 1980s.

Like four consecutive Met wins at Bank One Ballpark by the composite romp of 39-7, a sweep so complete that a month later the Diamondbacks changed its name to Chase Field, presumably in the hope that the marauding band of New Yorkers wouldn’t be able to find the joint when they came back to administer more punishment in 2006.

Like so many times some Met, whether instantly or vaguely recognizable from the perspective of nearly two decades on, did something that seemed momentous and unforgettable in 2005 — yet momentum faded, and a memory hole opened and swallowed up most of what I would’ve sworn wouldn’t be easily forgotten.

[8]Sometimes I wonder whatever became of 2005, beyond the turning of the calendar. Oh, the calendar turned, all right. When the Mets arrived at their new home in 2009, only Reyes, Wright and Beltran remained on a continuing basis from four seasons prior, and each of them had accomplished enough in 2006, 2007 and 2008 to shroud in Citi Field fog whatever they’d achieved across 2005. Other than David’s barehanded grab of a fly ball in San Diego, not much among what the final three did way back then ever got replayed or widely referenced again. Video of Mr. Koo’s wild ride was a hardy Subway Series perennial, but Mr. Koo was back in Korea. Marlon Anderson did a Recidivist Met stint, but saw his ITPPHHR goodwill lapse during one collapse or another. Aaron Heilman’s incarnation as a somewhat reliable reliever post-one-hitter also carried an expiration date, and he was traded the winter Shea was being demolished. Pedro Martinez’s first and only outing at Citi was in a Phillies uniform, for crissake.

[8]Sometimes I wonder whatever became of 2005, beyond the turning of the calendar. Oh, the calendar turned, all right. When the Mets arrived at their new home in 2009, only Reyes, Wright and Beltran remained on a continuing basis from four seasons prior, and each of them had accomplished enough in 2006, 2007 and 2008 to shroud in Citi Field fog whatever they’d achieved across 2005. Other than David’s barehanded grab of a fly ball in San Diego, not much among what the final three did way back then ever got replayed or widely referenced again. Video of Mr. Koo’s wild ride was a hardy Subway Series perennial, but Mr. Koo was back in Korea. Marlon Anderson did a Recidivist Met stint, but saw his ITPPHHR goodwill lapse during one collapse or another. Aaron Heilman’s incarnation as a somewhat reliable reliever post-one-hitter also carried an expiration date, and he was traded the winter Shea was being demolished. Pedro Martinez’s first and only outing at Citi was in a Phillies uniform, for crissake.

Yet I’m convinced there was something more at work than time going undefeated contributing to what I’m willing to label insidious if inadvertent 2005 Mets Erasure.

My hastily cobbled theory suggests virality may have existed on the Internet as a concept, but things weren’t as shareable as they’d soon become. Message boards brought Mets fans together in community (it was how Jason and I first crossed paths in the mid-1990s) and comments sections were attached to Web sites in order to promote polite discourse of relevant topics and issues among strangers who claimed common interests, but if you didn’t stumble into Mets material on your computer, you had to work a little to find it. When Jason initially proposed we begin a blog, I went to Google and typed in “Mets” and “blog”. Facebook was something only high school and college students used; YouTube was just launching; and Twitter was a year away. Watching Met highlights meant tuning into local newscasts if you were in New York, or waiting for ESPN to get around to that night’s Mets game if you weren’t. Most 21st-century Mets action that aired prior to the 2006 creation of SNY (if it didn’t involve Mike Piazza hitting a home run on September 21, 2001) wound up receding into video archives that would go largely undisturbed, as if psychically the Mets had packed for the future but never got around to fully unboxing their stuff once they moved there. If a person said he read something a diligent beat writer like Adam Rubin wrote that morning, chances were pretty decent it meant that person bought a physical copy of the Daily News and turned actual pages of a sports section, usually past too many Bronx-focused column inches. Clipping and saving was becoming a lost, then different art.

The times, they were a-changin’ — as times always are — but at the confluence of our Met and media concerns, the times where 2005 reside belong to a transition period where only one foot appears firmly planted on the precipice of what is now the present. My perspective might be skewed by the fact that I am sitting in the same room and at the same desk where I sat when I wrote my first post for Faith and Fear. The first time Jason hit “publish” on my behalf (I wouldn’t learn to do that for myself for a few weeks), I became an online content creator. Mentally, however I was still dragging my feet out of what was left of the past. Hell, I’d keep going out and buying the News until 2007.

In the first year this blog operated, everything was so fresh and so urgent. There were arcs and trajectories and spurts and streaks and curiosities and quirks and kicks to the gut and reasons to believe unfurling in every direction until the season’s conclusion demanded they land at a dead end. There were trades rumored but not made. There were grudges molded and held between Opening Day and Closing Day, only to be set free, because, honestly, you’d sound like a lunatic today if you tried to convince somebody you once got up in arms about old Miguel Cairo getting at-bats that could have been going to young Anderson Hernandez.

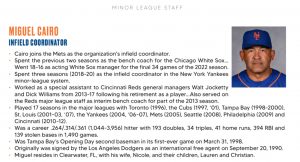

[9]In September of 2023, I heard Howie Rose mention that Miguel Cairo, then the Mets’ minor league infield coordinator, had worked closely with Ronny Mauricio in advance of Ronny’s callup to the majors. Cairo was a veteran utilityman by 2005 and not all that productive per the ascendant advanced metrics of the era or, to be honest, any old-school statistics you could find in the paper. I seem to recall a groupthink developed within the budding ecosystem we called the Mets blogosphere that something was very wrong with your team’s philosophy if it depended on somebody like Miguel Cairo, which, in turn made me empathetic to the guy — he was 31, I was 42, each of us kind of old for what we were doing — while concurrently making me wonder if maybe he didn’t need to soaking up a roster spot on a team that could benefit from a nice youthful infusion (ah, gray area). As Howie explained in 2023 how helpful Cairo had been to Mauricio and Mark Vientos and Brett Baty, I remembered there was a time the mere mention of Miguel would represent a virtual red cape inside an online bullring.

[9]In September of 2023, I heard Howie Rose mention that Miguel Cairo, then the Mets’ minor league infield coordinator, had worked closely with Ronny Mauricio in advance of Ronny’s callup to the majors. Cairo was a veteran utilityman by 2005 and not all that productive per the ascendant advanced metrics of the era or, to be honest, any old-school statistics you could find in the paper. I seem to recall a groupthink developed within the budding ecosystem we called the Mets blogosphere that something was very wrong with your team’s philosophy if it depended on somebody like Miguel Cairo, which, in turn made me empathetic to the guy — he was 31, I was 42, each of us kind of old for what we were doing — while concurrently making me wonder if maybe he didn’t need to soaking up a roster spot on a team that could benefit from a nice youthful infusion (ah, gray area). As Howie explained in 2023 how helpful Cairo had been to Mauricio and Mark Vientos and Brett Baty, I remembered there was a time the mere mention of Miguel would represent a virtual red cape inside an online bullring.

[10]Now it was many years later, and Miguel Cairo, who last played in the majors in 2012 (two years later than Anderson Hernandez did), was part of some rising rookie’s story, and Howie didn’t see fit to elaborate on Cairo’s 2005. I doubt any listener began to fume at the mention of the man’s name or rue his FanGraphs WAR of -0.5, because, well, that was a long time ago. It’s likely some Mets fan somewhere is still steaming at some 2005 Met or perhaps the entirety of the 2005 Mets for not coming through when crucial victory was a pitch or hit away (we were a half-game out of the Wild Card on August 30), but I find it hard to believe anybody instinctively or theatrically recoils at the possibility of being reminded of the shortfalls that loomed so large in the moment the way “1987” evokes Pendleton or “1988” evokes Scioscia. At most, a then-crushing defeat, like Braden Looper blowing an unblowable lead on a Friday night in Pittsburgh, looms in miniature, and only for somebody who relishes remembering to begin with.

[10]Now it was many years later, and Miguel Cairo, who last played in the majors in 2012 (two years later than Anderson Hernandez did), was part of some rising rookie’s story, and Howie didn’t see fit to elaborate on Cairo’s 2005. I doubt any listener began to fume at the mention of the man’s name or rue his FanGraphs WAR of -0.5, because, well, that was a long time ago. It’s likely some Mets fan somewhere is still steaming at some 2005 Met or perhaps the entirety of the 2005 Mets for not coming through when crucial victory was a pitch or hit away (we were a half-game out of the Wild Card on August 30), but I find it hard to believe anybody instinctively or theatrically recoils at the possibility of being reminded of the shortfalls that loomed so large in the moment the way “1987” evokes Pendleton or “1988” evokes Scioscia. At most, a then-crushing defeat, like Braden Looper blowing an unblowable lead on a Friday night in Pittsburgh, looms in miniature, and only for somebody who relishes remembering to begin with.

Yet, damn, 2005 happened for a whole year, I mean really happened, and we printed receipts.

Faith and Fear in Flushing preceded by a few months a notable format change on New York radio. It was one of those stories, akin to so many developments within a baseball season: huge in its day, yet recalled rarely outside the province of obsessives once that day grew distant. On June 3, 2005, WCBS-FM gave up on what remained of its long-running oldies format and flipped to JACK-FM. JACK-FM, which had attracted listeners in other markets, was terrestrial radio’s response to the iPod craze. It was supposed to be a music format that didn’t adhere to a music format. The slogan was Playing What We Want.

[11]Here at FAFIF-FM, we played what we wanted in stereo…or wrote what we wanted the way we wanted. We didn’t pretend to be newspaper reporters or, god forbid, talk radio hosts. We were fans/chroniclers. We chronicled the Mets, but we also chronicled being Mets fans. What it was like watching the Mets on MSG or Fox Sports Net New York or Channel 11. What it was like listening to the Mets on WFAN, if they weren’t bumped to WEVD. What it was like to go to Shea Stadium, as one would after pushing out of the 7 local at the Willets Point-Shea Stadium station and streaming with the throng headed down the spiral staircase that left a ticketholder in the shadow of Gate E. I’d take out my ticket, hope security wouldn’t bother my bag too much, shove my raincheck in my back pocket (I knew where I was going) and trusted the escalators supposedly gliding up toward Loge, Mezzanine or the Upper Deck were in working order. I bitched about the schlep every bit as much as I embraced my destination, warts and all. My, yes, there were warts. The PA was too loud. The food was too cold or hard or depressing, yet somehow costly. The puddle in the concourse — there was always a puddle in the concourse — was too much like a lake. The know-it-all in my row, the one who repeatedly insisted he would do a better job of batting than Carlos Beltran, was too much.

[11]Here at FAFIF-FM, we played what we wanted in stereo…or wrote what we wanted the way we wanted. We didn’t pretend to be newspaper reporters or, god forbid, talk radio hosts. We were fans/chroniclers. We chronicled the Mets, but we also chronicled being Mets fans. What it was like watching the Mets on MSG or Fox Sports Net New York or Channel 11. What it was like listening to the Mets on WFAN, if they weren’t bumped to WEVD. What it was like to go to Shea Stadium, as one would after pushing out of the 7 local at the Willets Point-Shea Stadium station and streaming with the throng headed down the spiral staircase that left a ticketholder in the shadow of Gate E. I’d take out my ticket, hope security wouldn’t bother my bag too much, shove my raincheck in my back pocket (I knew where I was going) and trusted the escalators supposedly gliding up toward Loge, Mezzanine or the Upper Deck were in working order. I bitched about the schlep every bit as much as I embraced my destination, warts and all. My, yes, there were warts. The PA was too loud. The food was too cold or hard or depressing, yet somehow costly. The puddle in the concourse — there was always a puddle in the concourse — was too much like a lake. The know-it-all in my row, the one who repeatedly insisted he would do a better job of batting than Carlos Beltran, was too much.

And there was still nowhere else I wanted to be. Let me tell you about it…

Maybe once a year one of the papers would write a ballpark feature. Usually we in the stands were just “the crowd” or “the fans”. We were said to have cheered or booed or maybe chanted something clever or obscene. We weren’t the story. We weren’t in the box score. At Faith and Fear (and, depending on their respective missions, at our compatriot blogs that sprung up in the same Spring ours did), we made ourselves as much the story as the players and the game. We made what it meant to be a fan central to the story, not only when we went to Shea, but when we got home, when we got up the next morning, and whenever we found ourselves thinking about the Mets, which was, we didn’t mind telling anybody who was reading, almost all the time. How a baseball fan functioned was the lifeblood of a baseball season, and I swear it felt like we had an exclusive in delivering that reality.

We weren’t JACK-FM. JACK-FM’s calling card, besides supposedly playing what they wanted, was having no personalities talking between songs (the gimmick didn’t last; whoever owned the 101.1 frequency switched it back to something approximating the old WCBS-FM two years later). We aspired to let who we were seep through the ball talk. It wasn’t enough to communicate that Beltran had gone deep or Reyes had stolen a base or Pedro had quashed a threat. We had to tell you where we were, what were thinking, how it elevated our hopes, how those hopes were validated or dashed, and maybe what we had for dinner. It was fans chronicling fandom. It was what we wanted to do. It was what readers connected with. The most resonant feedback we received in 2005 — and still sometimes hear, if not as much now that social media exists and everybody can express themselves for an audience — was some version of “I thought it was just me who was like that about the Mets.”

Baseball seasons are long affairs. Even with a game filling a roughly three-hour block on a given night or day 162 nights or days per year, that leaves waking hours without baseball being played, waking hours with thoughts of baseball orbiting the brain. It hardly seemed efficient to have this wonderful perch and fire it up only after a Mets game was over.

Informally first, then as a weekly feature dubbed Flashback Friday, I opened a portal to my past that intertwined with the Mets’ past. My journey was mine, but it wasn’t dissimilar to that of anybody reading about it. It wasn’t just me who was like that about the Mets. We’d all had that journey leading up to 2005. We’d all started somewhere as Mets fans. We all exulted, depending on vintage, in 1986 and 1969. We were all overcome by gloom in 1993 and 1979 and years like those. But you didn’t read about it in the papers. On this blog, you read about it as a matter of course. It’s how baseball worked in my head and probably your head. I didn’t see how I could spend 2005 writing about the Mets and limit myself to writing about the 2005 Mets.

And now 2005 is one of those long-ago seasons that I invite to intrude on the present.

[12]At the risk of loading a description, I haven’t been a “normal” fan since 2005. It rarely occurs to me to not filter my life through an orange-and-blue prism and muse if this or that is something that belongs on Faith and Fear. And that’s just life. It’s never occurred to me over these nineteen years to not care about everything the Mets do, though I’ve probably developed discernment over how much inherent value any single bulletin carries for blogging purposes. I certainly haven’t watched a game without instinctively thinking about what I will write, whether it’s a game for which I’m the designated recapper or not, because there’s always something to write eventually. Everything became and continues to be content. My ever present past lingers as prelude for what I might write tomorrow. If I stopped to realize how much older I am now than I was in 2005, it could give me pause, but it probably wouldn’t. I relish having lived through so much Metwise, but age as a figure simply doesn’t resonate for me in this realm. In this realm, I’m as old as I feel.

[12]At the risk of loading a description, I haven’t been a “normal” fan since 2005. It rarely occurs to me to not filter my life through an orange-and-blue prism and muse if this or that is something that belongs on Faith and Fear. And that’s just life. It’s never occurred to me over these nineteen years to not care about everything the Mets do, though I’ve probably developed discernment over how much inherent value any single bulletin carries for blogging purposes. I certainly haven’t watched a game without instinctively thinking about what I will write, whether it’s a game for which I’m the designated recapper or not, because there’s always something to write eventually. Everything became and continues to be content. My ever present past lingers as prelude for what I might write tomorrow. If I stopped to realize how much older I am now than I was in 2005, it could give me pause, but it probably wouldn’t. I relish having lived through so much Metwise, but age as a figure simply doesn’t resonate for me in this realm. In this realm, I’m as old as I feel.

As in 2005, I feel like writing about the Mets.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features [13]

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining) [14]

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years [15]

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity [16]

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock [2]

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time [17]

No. 18: Honorably Discharged [18]

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City [19]

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation [20]

No. 15: We Good? [21]