In the 1978 film Heaven Can Wait, veteran L.A. Rams quarterback Joe Pendleton, played by Warren Beatty, is in the prime of his life — “at my age, in any other business, I’d be young” — when he rides his way into an apparently fatal bicycle accident. An escort from above assigned to monitor such activity (Buck Henry) dutifully swoops up Joe to move him along on his celestial journey. Except the QB knew in his bones the accident wasn’t as fatal as it appeared, and therefore heaven really could wait. His assuredness led to this exchange between Joe and the escort’s supervisor Mr. Jordan (James Mason), the elegant gentleman charged with overseeing cloudbound operations.

JOE PENDLETON: I’m not supposed to be here.

MR. JORDAN: But you are here.

JOE PENDLETON: Well, you guys made a mistake.

Even as our collective attention shifts to hamate bones and positional switches reporting to Port St. Lucie in the company of pitchers, catchers, and everybody else, I’ve found myself thinking about that cinematic exchange from 48 years ago, overcome by the idea that someone winds up where he is not supposed to have been sent. I was directed in my mind to those lines and that thought in the aftermath of learning two one-time Mets had died just ahead of the beginning of Spring Training. “One-time” sounds right here. The first man was a Met for precisely a single season. The second of them was one of us for barely more than a month.

The passing that really brought it home was the second, that of Terrance Gore. Terrance Gore was a Met in 2022. He was 34 years old. Four Mets reporting to this very Spring Training are older. No, he’s not supposed to be here. In my heart, no baseball players are supposed to enter this sort of discussion. Because baseball players wind up as human beings regardless of the profession we grew up exalting, they inevitably wind up here, as any person will eventually.

But, if there’s justice, not a person who was 34. Not a Met from 2022 in 2026. Not someone I stood up to applaud on the final night of what is now a mere four seasons ago when he connected for his only base hit as a Met. Terrance Gore wasn’t a Met so he could bat. Buck Showalter brought him in to be his primary pinch-runner ahead of the playoffs. I trusted Showalter to know personnel the way Rocky Balboa trusted Mickey to train him for his longshot bout versus Apollo Creed. Late in Rocky, Mick tells Rock, “I want you to meet our cutman here, Al Silvani.” No further discussion needed, Al Silvani is the cutman. Early in September of 2022, Buck told us Terrance was in for Travis Jankowski, which is to say he would be in for the likes of Daniel Vogelbach and Tomás Nido should such lumbering Mets reach base.

Jankowski had done a fine job as Showalter’s pinch-runner of record before the Mets squeezed him off the 40-man, but Gore was a bona fide baseball celebrity to baseball fans who paid attention to baseball minutiae. Gore, listed as an outfielder, was the entire industry’s pinch-runner of record. He was famous for running for somebody else and getting rewarded for it handsomely, collecting three World Series rings despite rarely batting or fielding. He understood his mission on those championship rosters — the Braves’ in 2021, the Dodgers’ in 2020, the Royals’ in 2015 (when he had the decency to not enter a single World Series game) — was to be speedy in spots that could alter outcomes.

That was Terrance Gore’s role as a Met. He made it into five late-season games as a Met pinch-runner, plus a few others as a defensive replacement. In the bottom of the eight on a Sunday afternoon, as the Mets attempted to sweep away the pesky Pirates, Terrance put on what could be rightly called a pinch-running clinic.

He comes in to run for Nido.

He steals second.

He takes third as the catcher’s throw sails into center.

He comes home on Brandon Nimmo’s short single to left-center.

The Mets retake the lead.

The Mets win the game.

The essence of successful pinch-running in one quick 270-foot trip.

For Game 162 of 2022, Showalter granted Gore an entire nine innings to demonstrate his utility for the impending playoffs. As the starting center fielder, he lined a single into left off Erick Fedde of the Nationals. As baseball fans, we relish jumping to our feet and clapping when a player successfully completes what isn’t his standard assignment. Terrence hadn’t registered a base hit since 2019. It wasn’t his job, but now he had done it in front of us, and we did not hesitate to express our appreciation. We’d only been acquainted with Gore for a month, but we wanted to let him know we liked what he was doing.

The last thing Terrance Gore did, having made the postseason roster, was pinch-run in the second game of the National League Wild Card Series against the Padres. Darin Ruf led off the home sixth by helpfully placing his body between a pitch and the catcher’s mitt. The DH was HBP, and how he’d be PR for. Gore in for Ruf. The Mets were down one in the series and up one in the ballgame. What a perfect situation for a player of Terrance’s skills to make a difference. This was a man who had pinch-run 67 times in regular-season play since coming to the big leagues in 2014, plus eleven more in the postseason with this appearance. He was a specialist and this loomed as a special moment.

Then Nido grounded to second, instigating a 4-3 DP that not even the speediest pinch-runner could upend. Sometimes that’s how the ol’ ballgame goes. Sometimes that turns out to be the last time you see a ballplayer playing ball. Gore, penciled in as designated hitter, would be pinch-hit for when his slot in the order next came around. Buck didn’t have a situation for him in deciding Game Three, the one that eliminated them, and that was the end of Terrance Gore’s Mets career and, as it turned out, baseball career. The Mets wanted to outright Gore to Triple-A. He had the right to refuse and elected free agency. Nobody signed him, and that was that as far as we knew.

Not even three-and-a-half years later, you read Gore has died at 34, reportedly from surgical complications, and you can’t quite fathom it. You never can with ballplayers who were playing for your team just the other year, which might as well be just the other day. Gore is the fifth late Met whose tenure with the club took place entirely in this century, the only one whose breadth of major league experience postdates Shea Stadium. Shea Stadium lingers in the distant enough past that we’re now down to one potentially active MLBer, the as yet unsigned Max Scherzer, who can say he played there. If we mark time by stadia, anything we hear about Terrence Gore lands as relatively current, never mind indisputably recent. The 2022 Mets? I know we just let some of those guys go, but a few are still Mets on the precipice of 2026; Francisco Lindor, Mark Vientos, and Francisco Alvarez were in the starting lineup alongside Gore on October 5, 2022. Citi Field? It’s where we’ll be focusing our attention at the end of March. This March. I was just there in September for Closing Day, just as I was just there in October of 2022 for Terrance Gore’s lone Met hit.

If we imagine our lives as following some kind of path, à la Heaven Can Wait, we could do worse for a roadmap than a baseball diamond. Home to first. First to second. Second to third. Third to home. It may not work that way in life, but it’s kept baseball humming in fine fettle. Terrence Gore didn’t even have to go home to home around the diamond most games. He’d usually start at first base. He was in as a pinch-runner to pick up for the guy who found his way there from home plate. Baseball allows this, somebody fast helping out somebody who’s not. That was what Terrance Gore did so well that teams contending for a title sought him out and showed their faith in him to do it some more.

The bulk of Terrance Gore’s baseball career was about getting from only first to home as fast as possible. By that measurement, somebody owes this man an extra ninety feet.

Before the loss of Gore and one other Met this February, there were a half-dozen far older Mets who died between the end of the 2025 season and the turn of the calendar to 2026: infielders Sandy Alomar, Sr. (81), Larry Burright (88), and Bart Shirley (85); outfielder George Altman (92); first baseman Tim Harkness (87); and starting pitcher Randy Jones (75). I’m also compelled to mention reliever Bill Hepler (79), who died in August without us taking a moment to note his passing. Those were seven Mets from what is unquestionably a long time ago. Six of them were Mets in the 1960s, a decade that hasn’t been active for more than fifty-six years. Alomar and Jones are the only ones I personally remember as major leaguers, and my instinct is to say I’ve been watching baseball almost forever.

Yet it was too soon for all of them to go, because baseball players became baseball players before the primes of their lives even began, and the people who cared most about them were kids whose lives had barely begun. We, those kids, get older and if we think of baseball players from our youth, we don’t see men who’ve aged into their so-called golden years. We see the athletes. We see the Mets. We see ourselves, from the inside out, viewing them as Topps intended. We don’t know it at that age, but those are their own kind of golden years, and a baseball player’s name is license to revisit them any time it occurs to us.

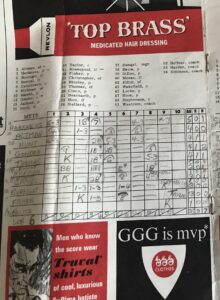

If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game!

If we were lucky enough to experience it, we see Tim Harkness smashing that walkoff fourteenth-inning grand slam to beat the Cubs at the Polo Grounds in 1963 and summon that untoppable thrill all over again. Or we can reseat ourselves at brand new Shea Stadium on April 17, 1964, peer up at that gigantic scoreboard, and fill out a scorecard with the names of the first nine Mets to start a game there, including HARKNESS 3, leading off and playing first; ALTMAN 9, hitting second and batting right; and BURRIGHT 4, batting eighth and playing second. We could begin to imagine what might be possible in this place. It’s Shea. It’s the present and it’s the future. The World’s Fair is next door and the sky could be the limit…and if the sky is a stretch, considering we’ve spent our first two years in tenth place, then Row V of the Upper Deck will do as a manageable hike. Top to bottom, this is where we and the Mets live. It will never occur to us that someday the National League won’t be stocked with players who will be able to say they played here, because where else would they play when they come to play the Mets? Why, even the best American Leaguers will be dropping by this July for the All-Star Game!

Baseball players being human beings in their spare time precludes actual immortality. But isn’t it fun to remember the eternal excitement they evoked when we weren’t particularly judgmental, especially when they wore the uniform of our favorite team? In that respect, Pavlov’s Intro for us of a certain age was surely the highlight montage that ushered onto Channel 9’s air Mets games during the heart of the 1970s, when Shea continued to stand tall. At first sight and sound of that montage, the young Mets fan heart would race and the young Mets fan mouth would salivate. The Mets skyline logo spun into place. The instrumental version of “Meet the Mets” blared. Mets players were in action, and I mean action, with one film clip succeeding another in rapid fire procession.

A Met swinging. A Met throwing. A Met leaping. Finally, a Met sliding into home and scoring to the greatest of musical scores, all in glorious grainy color (or black & white, depending on the TV set available to you). Edits were made to delete or incorporate this Met or that as roster revisions necessitated, but every last Met shown was clearly intrinsic to Team Highlight…except, maybe, for one Met who made the montage one year without ever truly fitting within its pulsating confines.

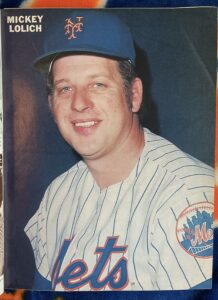

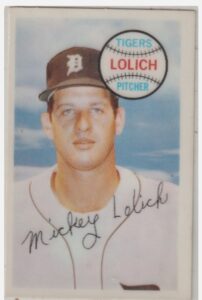

Before Warner Wolf made doing so fashionable, Mickey Lolich went to the videotape. Mickey’s snippet, spliced into the 1976 introduction, was not on film like everybody else’s. He had never been properly filmed as a Met, thus WOR was compelled to insert a frame or two from the telecast of his first start in April, lest the station stand accused of not keeping current. I wouldn’t say it portrayed the lefty import in action. Lolich, the only new Met on the Shea Stadium scene when that season commenced, stood on the mound for an instant. Maybe he went into his windup. I don’t remember if he threw a pitch. In the mind’s eye, he was just kind of there until we could return to the Mets who looked like they belonged on the Mets.

How’s that for a Met-aphor, vis-à-vis “I’m not supposed to be here”?

Mickey Lolich was the first Met to die this February, a couple of days before Terrance Gore. Lolich was 85, that age when you’re not bowled over by such a bulletin, even if it regards a ballplayer you remember well from when you were 13. With news of his passing, the lefty was acknowledged far and wide in baseball circles as one of the great Detroit Tigers. I heard about his death, and I’ll confess to remembering him near and narrowly as a New York Met from central miscasting — a dependable source of on-field personnel for us through the years. Listen, we’ve had loads of players who just passed through, plenty of others who didn’t live up to their established reputations upon becoming Mets, quite a few who were on the irreversible downside when they donned our duds (former Cy Young winner Randy Jones, for example). The inclination is to tick off a dozen disappointments who have spanned the decades, as if to show each other our rooting scars and congratulate ourselves on our perseverance.

Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich.

Lolich in 1976, however, felt like his own case study in miscast Metsdom. We didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. He, it seemed, didn’t know what he was doing on the Mets. Long before the Alex Rodriguez free agent contretemps of 2000, Lolich personified the 24 + 1 equation Steve Phillips floated as the rationale for not signing A-Rod. It wasn’t a matter of Mickey demanding special treatment that would set him apart from his teammates. It was more like he landed as an alien presence in our midst and never quite melted into the montage. Twenty-four Mets. One Mickey Lolich.

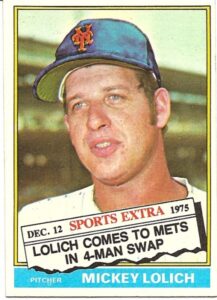

On December 12, 1975, the Mets traded Rusty Staub and minor leaguer Bill Laxton to the Tigers for Mickey Lolich and minor leaguer Billy Baldwin. There, I thought, went so much that was fun about 1975, while simultaneously inferring that 1976’s version of the Mets was diminished before it began. No 12-year-old had ever been as wrapped up in an also-ran as I was in the 1975 Mets, and about half my goodwill had just been tossed aside. Rusty Staub, besides being Rusty Staub to us ever since we traded for him in 1972, had just reached one of those heretofore unreachable statistical stars. Our fixture in right field became the first Met to crash the 100 RBI barrier in ’75. It took fourteen seasons for any Met to drive in triple digits. It took fewer than three months for Mets management to decide such a skill set was disposable. Surprise, surprise, M. Donald Grant didn’t want to keep around a beloved veteran star at the top of his game, one whose strong personality apparently clashed with his idea of how a player should act (which is to say thankful to the opportunity to call Mr. Grant his employer). Had Rusty made it through five years as a Met, he could veto a trade. Player empowerment gave Grant the worst kind of rash. It therefore became GM Joe McDonald’s job to ship Staub somewhere else ASAP and get something of value in return.

Mickey Lolich was a name. In the American League, his name had been synonymous with 2,679 strikeouts, the most recorded by any lefthanded pitcher in baseball history as of the Bicentennial; three complete-game victories in the 1968 World Series, culminating in his besting Bob Gibson on two days’ rest to take Game Seven (not to mention a home run he hit off Nelson Briles in Game Two); and a pair of 20-win seasons a few years later. Had Vida Blue not been so spellbinding over the first four months of 1971, Lolich could have claimed he was a victim of Cy Young robbery. As was, Mickey, as runner-up, won more games than anybody in the majors in ’71 (25), started more games than anybody in either league (45), struck out the most batters in baseball (308), and posted an innings total 42 frames beyond that of any counterpart (376). He followed all that with a 22-14 mark in 1972, pitching the Tigers to the AL East title and doing his damnedest to get them back to the Fall Classic. In an ALCS recalled today mainly for Bert Campaneris flinging a bat at Lerrin LaGrow in Game Two, Lolich pitched into the eleventh inning of Game One, only to take a hard-luck loss, and was no-decisioned despite going nine innings and giving up a lone run in Game Four.

Jesus, that guy was good. And you would have loved to have that guy from 1968 or 1971 or 1972 on the Mets. What a highlight player he would have been. As 1976 approached, those peaks were fading fast in time’s rearview mirror. Lolich’s last two years as a Tiger saw him lose 39 games, albeit for a team that was altogether past its late-’60s/early-’70s prime. Numbers unavailable to the baseball-consuming public in 1975, particularly his Baseball-Reference WAR of 4.0, indicate he was done no favors by pitching for the 102-loss Tigers. On the other hand, his having turned 35 was a matter of public record. All those innings on all that Lolich (bulky would be a kind description) had to have taken a toll after so many years.

At his age, in any other business, he’d be young. In 1976, in baseball, he was getting on.

Yet the Mets tried to treat him as a get. Convinced of the durability of their Kingman-Unser-Vail outfield, GM Joe McDonald figured a lack of offense, even sans Staub, wasn’t an issue that was going to bedevil the Mets. What the team fronted by Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, and Jerry Koosman needed to do, according to McDonald, was trade its most reliable stick for another arm. “One of the reasons we didn’t win last year,” McDonald rationalized upon announcing the trade, “is because we didn’t have a solid No. 4 starter. Now we go into a town for a three-game series, and the other team knows they are going to face one of the four in every game.” Too much pitching is rarely any team’s problem, but whither the offense? Whither the 105 RBIs that just went out the door? Whither the foot Mike Vail broke playing basketball during the offseason? Joe McDonald plans, the entity Mr. Jordan works for laughs.

Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal.

Lolich needed to be persuaded he wanted to be a Met. He already had that 10-and-5 protection — ten years as a big leaguer, five with one team — that the Mets feared Staub would attain. Though he felt disrepected by the Detroit front office, he’d been a Tiger since 1963. The area was what he and his family knew, and he wasn’t necessarily raring to say yes to moving to the city the President of the United States (Michigan’s own Gerald Ford) had just told to drop dead. McDonald needed an answer as the Winter Meetings wound down, not just to help clarify the Mets’ plans, but to beat the then-extant Interleague trading deadline. Come to New York, Mickey, was the big pitch to the big pitcher. A guy with your credentials can do well off the field in the Big Apple. Agreeing there might be commercial benefits tied to pitching in the nation’s largest market, believing the .500-ish Mets were more likely to win than the cellar-dwelling Tigers, and confirming he’d be suitably compensated for packing up and heading east, Lolich signed off on the deal.

His introduction to the Mets nonetheless represented a shock to his Detroit-defined system, and it was made no smoother by a Spring Training that was delayed past St. Patrick’s Day thanks to an owners’ lockout. Among an informal gathering of stretching and tossing Mets, Cardinals, and Pirates in St. Petersburg, the southpaw admitted nobody in this league was familiar to him, not even on his own team. Of longtime catcher Jerry Grote, who was as much a fixture to the Mets’ staff as Bill Freehan had been to the Tigers’, Lolich told Newsday’s Bill Nack, “If he walked up to me now, I wouldn’t know who he is.”

Yet here came Mr. Lolich, wearing a boxy Mets jersey, starting the third game of the new season. Seaver won on Opening Day. Matlack threw a 1-0 shutout the second day. Lolich couldn’t maintain the momentum, lasting only two innings. He’d made two errors and had given up three Expo runs on one of those trademark windy April Shea afternoons. His spot in the batting order came up in the bottom of the second with the bases loaded and two out. Rather than let Lolich take his first swings since pre-DH 1972, new manager Joe Frazier sent up John Stearns to pinch-hit. Stearns flied out. With the Mets leaving fourteen runners on bases, Frazier and Lolich were both on their way to their first National League losses.

Things would get intermittently less horrific. It took four starts for Mickey Lolich to earn an NL win, but he did it in style on April 26, going the distance and striking out nine Braves, while working harmoniously with Ron Hodges, who, like Grote, he’d eventually met. His wins legitimately impressed. A complete game at San Francisco in mid-June. A shutout over St. Louis as June ended. Another whitewashing when Atlanta returned to town right after the All-Star break. On August 8 in Pittsburgh, as Hurricane Belle bore down on New York, Mickey withstood storm clouds of his own. He gave up eight Pirate hits, walked one Buc, struck out nobody, yet remained on the mound all nine innings in posting a 7-4 victory. It was the third and last time a Met pitcher ever won a complete game with zero strikeouts, and it was done by a pitcher who, entering that season, had struck out more batters than any pitcher in baseball history besides Walter Johnson and Bob Gibson. “Sometimes,” the lefty explained in April, “I’ll change my style of pitching two or three times a game.” Clearly, the veteran could put his versatility to optimal use.

Lolich was the personification of that little girl with the curl cliché Ralph Kiner loved invoking. When he was good, he was very good. Sometimes he’d be more than pretty good but his batters weren’t up to snuff. Lolich threw eighteen quality starts — at least six innings pitched, no more than three earned runs allowed — yet Mets lost nine of them. Come summer, Bob Murphy was regularly using the word “snakebit” to describe Lolich’s season. Sometimes the bad-luck serpents couldn’t be blamed, as the pitcher who turned 36 on September 12 simply wasn’t able to keep pace with Seaver, Matlack, or soon-to-be Cy Young runner-up (to Randy Jones) Koosman. A fourth starter, no matter how accomplished, tends to perform like a fourth starter. Lolich’s 3.22 ERA wasn’t the sparkling stuff usually posted by Met aces of the day, but it probably deserved better than an 8-13 won-lost record on a third-place club that went 86-76. His ERA+, a metric conceived decades later to provide context for how a pitcher performs among all of his peers, was 101, or ever so slightly above average.

As a 13-year-old Mets fan in 1976, recently Bar Mitzvahed and everything, I’d like to think I had reached the age of reason. I could reason that though Lolich couldn’t keep his earned run average below three and couldn’t compile more wins than losses, that he was not bad. I kept telling myself that. He’s not Seaver, and he’s no longer the guy who gave Vida Blue a run for his money, but he’s OK. He can’t help it if they don’t score for him. And he can’t help it if we never should have traded Rusty Staub. Yeah, I still missed Rusty Staub. Did any Mets fan not? The group of Tigers Rusty went to weren’t dramatically better than the set Lolich left, but they sure seemed to be a lot more fun than the 1976 Mets. The main reason was Mark “The Bird” Fidrych talking to the ball before throwing it past batters en route to a literally sensational 19-9 year, but don’t overlook the joie de vivre provided by Detroit’s new right fielder and sometimes designated hitter. Staub played 161 games for the Tigers, drove in 96 runs, and was elected to the AL All-Star team by discerning fans everywhere. If Rusty missed us like we missed Rusty — both in the affection and run-production sense — it didn’t show in his stats.

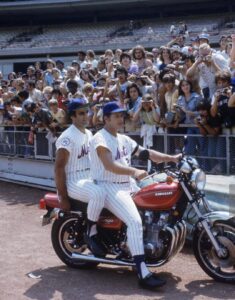

Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing.

Lolich, meanwhile, failed to find film-clip permanence in New York across his 31 starts. Besides not being Rusty Staub and not pitching as well as his rotationmates, there wasn’t much to mentally scrapbook. Decades later, an image did make the social media rounds. It featured Mickey on a motorcycle on the first base warning track at Shea, with Joe Torre ready to hitch a ride, Richie Cunningham to Mickey’s Fonz. The Mets were holding Camera Day, and Mickey gave the fans a most unusual pose. Perhaps he was most comfortable on his bike because it allowed him to daydream he was riding the hell away from Flushing.

With a year remaining on his contract, Mickey Lolich let the Mets know whatever they were planning for 1977, they could do it without him. The native Oregonian never stopped missing Michigan. It was home to him and his family. New York was a yearlong business trip. Lolich elaborated on his exit strategy for the Daily News in December of ’76:

“The season was not fun. On the days I wasn’t pitching, life wasn’t fun. I was very happy with the Mets. They were some of the finest players I’ve ever been with, and I got along well with the front office. I was disappointed in my record because I pitched better than that. So did Tom Seaver. People ask, what was wrong? Nothing was wrong. But the Mets definitely need a power hitter to help Dave Kingman.

“And the first two months were difficult with the people ridiculing me and belittling me. I got letters and heard them telling me they wanted Staub there instead of me. Sure, it reflects on me. I’ve been playing in the big leagues for 14 years. Now I want to be home.”

With that, Mickey Lolich was retired. Then, after his Mets contract officially expired, he unretired, filed for that newfangled free agency, and gave pitching one more shot, this time out of the bullpen as a reliever for the San Diego Padres, farther from Michigan than New York was. He toed the Shea mound once in his two Padre years, on August 17, 1978, throwing three shutout innings and notching his first (and only) National League save in support of Gaylord Perry’s 260th career win. Per Don Williams in the Star-Ledger, Mets fans booed Lolich when he entered he game, booed again when he batted, and cheered when he struck out. “Sure I expected it,” the ex-Met said of his reception. “That’s New York.”

At the end of 1979, Lolich decided he was done being a big leaguer for real. Back to Michigan he went for good, occasionally receiving the “where are they now?” treatment as the pitcher who went from putting up zeroes to turning out doughnuts at Lolich’s Donuts & Pastry Shop in Lake Orion, Mich. Hockey great Stan Mikita owned a place like that in Wayne’s World, but his establishment was fictional. Lolich’s new line of work was genuine. The Times visited him when the Tigers made the World Series in 1984, stressing how earning 217 major league wins had been Lolich’s then, while baking “400-dozen doughnuts a day” accounted for his now. Tensions were dissipating between him and the team he was remembered succeeding for, and, as the years went by, the idea Tigers ever traded him away must have seemed as absurd in those parts as it is in our neck of the woods that the Mets felt the need to rid themselves of Rusty Staub.

For the rest of his life, doughnuts or no doughnuts, Mickey Lolich was introduced; referred to; and thought of first, foremost, and practically exclusively as MVP of the 1968 World Series, one of the all-time great Detroit Tigers. However he spent his 1976 was just some fine-print detail. Lolich would make his final appearance at Comerica Park in 2023 as part of a pregame 55th-anniversary celebration of the championship his left arm made possible. He and a handful of his ’68 teammates stuck around to take in a promising performance from emerging Tiger ace Tarik Skubal. Skubal struck out nine, a fairly Lolichian total, but the kid on the verge of back-to-back Cy Youngs went only five innings. They were scoreless, but there weren’t that many of them. Afterward, the young lefty berated himself for not lasting seven — not nine, but seven. When Tarik tossed his first complete game in 2025, it left him 194 shy of Mickey’s career total.

Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!”

Not surprisingly, Lolich and his fellow champions were provided a suite to watch that Skubal start in 2023. Yet sixteen years after his week in the October 1968 sun, the 1984 Tigers were only “gracious” enough (Mickey’s word) to furnish the hero from their previous World Series run with upper deck tickets for the ALCS clincher at Tiger Stadium versus the Royals. It was the first time he’d been to a game in a few years. Sitting far from the dugout and above the “guys in silk suits” notorious for filling box seats during the postseason opened his eyes a bit. “I finally found what really happens in the stands,” he told Jane Gross in the Times. “How devoted those people are to the ballplayers! How much they adore them!”

Yes, it’s how we felt about Rusty Staub, and were bound to feel the opposite of when we encountered anybody who got in the way of our devotion to and adoration of Le Grand Orange. Nothing personal, Mickey. That’s New York, too.

Beautifully written piece that brings a tear to my eyes. And btw, RIP Buck (Henry). Funny, funny guy.

Today’s generation of Mets fans just don’t realize how lucky we are to have Steve Cohen and David Stearns calling the shots. 18 years of Jeff Wilpon was certainly awful, but at least there were a few good seasons. Directly or indirectly, the cold-hearted, bone-headed M. Donald Grant ran a virtual All-Star team out of town. The Staub trade was only one such blunder. Start with losing Whitey Herzog, throw in the Seaver trade, the 4-team deal that wasted Matlack, trading Tug McGraw to the Phillies, Nolan Ryan for Jim Fregosi, not investing any money into scouting, the farm or the facilities. That team was set to be a dynasty and he flushed it down the crapper.

Mickey Lolich pitched 200 or more innings in 12 straight years, including 4 straight years of 300 or more innings. He pitched 376 innings in 1971. How many pitchers have pitched that many innings total in the last 2 years? 5 maybe? How is this guy not in the Hall of Fame?