The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 2 February 2021 12:15 pm So 2020 was a … strange year, on the baseball field and everywhere else. (You might have noticed.) A global pandemic forced a jury-rigged, stop-start 60-game baseball season, which the Mets proceeded to botch, passing up perhaps the easiest path to the playoffs ever available. Even beyond that, though, 2020 was what we now know was the last year of the Wilpon era, with the usual roster heavy on retreads and castoffs and prospects turned suspects.

2021 is likely to be another incomplete, at least somewhat experimental baseball season, but it already promises to be a very different one in terms of payroll, philosophy and — one hopes — results. And that’s made 2020 already feel like it’s a long time ago.

But we have our duties regardless, and among them is welcoming another class of matriculating Mets to The Holy Books!

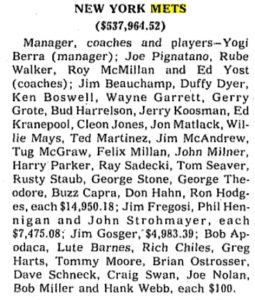

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts (we got a new one this year), and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or got stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost. Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts (we got a new one this year), and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or got stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.

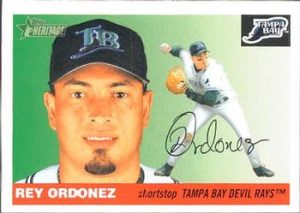

If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At the end of the year I go through the stockpile and subtract the maybe somedays who became nopes. (Lots of nopes — tough business, baseball.) Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Still here after all that? Hell, it’s winter — where would you go? Well then:

Andres Gimenez: One of the brightest spots of 2020, Gimenez is now an employee of the Cleveland Soon-to-No-Longer-Be-Indians. (See what we mean by 2020 seeming like a long time ago?) Gimenez arrived earlier than expected and immediately paid dividends, quickly endearing himself to us as one of those players whom you can rely on to do the right thing without needing to think about it. And he showed good range and hands at all three infield skill positions, making him essentially the opposite of a decade or so of Mets. The Mets traded that potentially bright future, but in return they got back Francisco Lindor, a bona fide superstar with a chance to become a franchise cornerstone and New York icon. That’ll work! Some crummy Bowman card, but he has a ’21 Topps card on deck.

Jake Marisnick: A plus center fielder, Marisnick showed flashes of also being a decent hitter in Houston, and essentially stepped into Juan Lagares’ role in New York, complete with the limitations and questions we’d had about Lagares. (The Mets, entertainingly, then brought Lagares back. With his No. 12 adorning the back of Eduardo Nunez, Lagares wore 87 for a single game, then switched to 15. The head, it spins.) We never got a verdict on Marisnick because he was mostly hurt; now he’s a free agent. A dollop of extra credit for being the Mets’ “wet guy,” though one could argue the optimum number of wet guys per club is zero. Got a cool 2020 Topps Update card out of the whole affair, at least.

Dellin Betances: Gigantic former Yankee power reliever returned to duty across town and demonstrated he wasn’t fully recovered from the injury woes that wrecked his 2019. (Here’s a reminder that you should be much more worried about hearing a pitcher has a bad shoulder than that he has a bum elbow.) Importing him was a familiar Wilponian gambit: “Let’s give this recuperating player a key role because if the healing process goes really really well he’ll be a bargain.” How many times did the Mets try this gambit post-Madoff? How many times did it work? Betances will be back, and hopefully useful this time. Got a terrible horizontal card in Topps Update, and if you’ve read this column before you’ll be familiar with my warnings that horizontal baseball cards lead to drug abuse, Satanism and spontaneous combustion. Subbed that horror for a nondescript but properly vertical Topps Heritage card.

Eduardo Nunez: Useful veteran coming off year wrecked by injuries … see above and sigh. Nunez, predictably, got all of two ABs for New York, though hey, he was 1-for-2. Got a groovy Topps Update card in which he’s wearing shades. It’s the little things. Sometimes it’s only the little things.

Hunter Strickland: Annoying Giants blowhard saw his career hit the skids a few years back, a career tumble that culminated with his washing out with the Nats in the run-up to the 2020 season. Except it didn’t culminate with that, because the Mets plucked Strickland off the scrap heap, dusted him off and marveled that someone had discarded a perfectly good reliever. Strickland soon disabused them of this notion and was quietly returned to the scrap heap where he should have stayed in the first place. Perhaps this is as good a place as any to stop and sigh with relief that our baseball team is (presumably) done behaving like it’s in the rag trade. Some stupid old Giants card.

Rick Porcello: The Mets imported Porcello and Michael Wacha for the back of their rotation (which should have still included Zack Wheeler, but that’s another post), only to wind up needing more from both of them when Noah Syndergaard’s elbow exploded and Marcus Stroman opted out. Porcello seemed like a reasonable gamble, having won a Cy Young award in 2016 and pitched capably in 2018, but he’d interspersed those campaigns with dreadful 2017 and 2019 seasons. Porcello grew up as a Mets fan and seemed like a good guy in the clubhouse, but he was terrible outside of it, giving up hits by the bushel and forcing the bullpen to do things it couldn’t do. He gets a Topps Heritage card — the ’20 Heritages recycled the 1971 design, which is far from my favorite but seemed perfect for such a deeply strange year.

Michael Wacha: Like Porcello, Wacha brought a track record of past success and an iffy future to a present-day gig at the back of the rotation. Like Porcello, the Mets wound up asking more of him than was wise or arguably fair. Like Porcello, he largely didn’t deliver, giving up an ungodly number of home runs. Wacha’s only 29, but fixing whatever’s wrong with him is now somebody else’s problem. Topps Heritage card in which he’s in the same pose as Porcello, appropriately enough.

Chasen Shreve: A skinny reliever who looked like he’d been living under a bridge, Shreve was a nice surprise in an underwhelming bullpen, dominating lefties and holding his own against righties. The Mets non-tendered him after the season, which seemed a bit mean, but then middle relievers are spaghetti thrown against a wall, and one year’s success or failure often says little about the next year’s. Ask Brad Brach — or a hundred other guys — about that. 2019 Topps Heritage card in which Shreve is a Cardinal, clean-cut and unrecognizable.

David Peterson: He shouldn’t have been in the rotation at all, and wound up leading the club in wins. 2020, wooo! Peterson was pressed into service when the rotation was undone by Wilponian gimcrackery, injuries and opt-outs, and opened eyes in his debut against the Red Sox, showing poise beyond his years and battling his way to a victory. He continued to impress all season, riding a plus slider and a brainy approach to pitch selection and location. He’ll be asked to do less in 2021, which is both wise and the kind of thing that wouldn’t have happened under the previous regime. Old Bowman card in which his Mets uniform is a Photoshop job. A week from now he’ll have a ’21 Topps card. (Please don’t let it be a horizontal.)

Brian Dozier: A former star with the Twins and a useful piece with the Nats, Dozier showed very little with the Mets, was shoved aside by a resurgent Robinson Cano, and was soon off the roster. Years from now you’ll take a Sporcle quiz about Mets second basemen and Dozier’s line will still be blank when time expires. When his name materializes, you’ll shrug and agree you had no chance at that one. Old Nats card.

Ryan Cordell: A defensive specialist who’s never learned to hit a breaking ball, Cordell didn’t do much with the Mets but somehow got a Topps Heritage card. Every year there’s a guy who inexplicably gets a baseball card, which as an OCD card-collecting doofus I welcome despite the attendant bewilderment.

Franklyn Kilome: A tall, skinny kid with a live arm, Kilome came over from the Phillies in the Asdrubal Cabrera trade. He was damaged goods when he arrived, missing the entire 2019 season due to Tommy John surgery. Oh, those wacky Wilpons! Kilome pitched well in his first outing but after that was consigned to irregular mop-up work — the dreaded Mike Maddux role. It didn’t go well — it didn’t go well at all — but it’s not fair to judge him for that. Hopefully we’ll have something kinder to say in the future. Old Bowman card, Photoshopped uni.

Jared Hughes: Famous for sprinting in from the bullpen, to the apparent annoyance of former teammate J.T. Realmuto, who will not be a Met so fuck him. I said “famous” but OK, I didn’t remember the sprinting until I Google’d Hughes, which I did because I recalled nothing about him except that he was not, in fact, the same guy as Chasen Shreve. (Not only is he his own discrete person, he’s also right-handed.) Pitched pretty well, now a free agent, middle relievers, spaghetti against the wall, etc. Topps Heritage card in which he looks like Chasen Shreve, which is just mean.

Billy Hamilton: Famously fast center fielder and base stealer arrived in a minor trade with the Giants, hit .045 and made a horrific base-running error in a tight game against the Phillies, after which his services were no longer required. A boisterous cheerleader from behind the dugout rail, for whatever that’s worth. 2020 Topps Update card … in which he’s a Giant.

Ali Sanchez: Young, defense-first catcher got a call-up amid Wilson Ramos’s various woes and Tomas Nido testing positive for COVID. He didn’t make much of the chance, but he did collect his first big-league hit, and he only just turned 24. Speaking of young catchers, pour one out for Patrick Mazeika, who logged time on the Mets’ roster but never got into a game. He’s 27 and hit .245 in Double-A in 2019, making you wonder if 2020 was the closest he’ll ever get. For now, Mazeika’s the 10th “ghost” in Mets history and the third without a big-league appearance for any other team. Here’s hoping for another sighting of both young receivers; for now, Sanchez gets a Topps Heritage Minors card as a Rumble Pony. Whatever the hell that is.

Ariel Jurado: Beefy Rangers castoff was imported for a spot start against the Orioles, got destroyed, and was never seen again. Jurado has three total Topps cards — an Update card and two team factory-set issues. This would be quirky if he’d sported an ERA a third the size of what he did; since he didn’t, it’s annoying.

Miguel Castro: A flamethrower who could be a valuable setup guy or even a closer if he could throw strikes more consistently, which might augur future success and might augur nothing but further muttering, seeing how you could have said the same thing about several thousand pitchers in baseball history. Castro’s on his fourth organization and the Orioles gave up on him, which ought to tell you something; on the other hand, he only just turned 26, so keep hope alive! Skinny to the point that every time he came into a game I wanted the trainer to bring him a cheeseburger. Rockies card from a while back.

Robinson Chirinos: A part-timer until his mid-30s, Chirinos found his groove when most catchers with his CV would have feared becoming unemployed, putting up three years with double-digit homers from 2017 through 2019. That was enough for the Rangers to give him a one-year deal at nearly $6 million with an option for 2021, but Chirinos never got untracked and wound up with the Mets, where things didn’t go much better than they had in Texas. My goodness but catcher turned into a black hole in 2020, didn’t it? Don’t forget the Mets also brought Rene Rivera back! Topps Update Rangers card sporting an INAUGURAL SEASON tag for Globe Life Field, which hosted the World Series despite the Rangers not being involved. And you thought our year was weird.

Erasmo Ramirez: A rotund 30-year-old, Ramirez was serviceable for a stretch with Seattle and Tampa Bay but fell off a cliff in 2018. The Mets signed him to a minor-league deal, brought him up in September and probably wished they’d done so earlier, as he proved one of the bullpen’s more reliable arms down the stretch. Alas, he’s now an employee of the Detroit Tigers. Hey, spaghetti against a wall. Pawsox minor-league card scrounged up on eBay.

Guillermo Heredia: His first hit with New York was a home run; afterwards, he talked about how Robinson Cano had been a father figure for him since he came to the U.S. from Cuba, which makes you wonder how he took a certain bit of offseason news. Cano has taken a wrecking ball to his reputation and his Cooperstown chances, but Heredia’s the most recent in a long list of guys who said glowing things about him as a teammate and mentor. Damn shame, that. Anyway, Heredia’s signed on for another tour of duty in 2021, and has the speed and glove to be a perfectly serviceable fourth outfielder. Topps Heritage card as a Mariner.

by Greg Prince on 2 February 2021 12:20 am It wasn’t that long ago, yet it was long enough ago that it was a face-to-face conversation (remember those?). The topic was Met managers of very recent past and very near future. Mickey Callaway was ex-manager of the Mets by then. The person I was talking to was somebody whose observations I appreciated as earned and accurate. When the topic turned to Callaway, I prefaced my own impression — that he wasn’t particularly well-suited to the job from which he’d been removed — with the caveat “I’m sure he was a nice guy,” because, frankly, Callaway seemed nice enough on radio and TV when not trying to explain away losses, and, also frankly, I didn’t want to come off as somebody simply piling on a guy who nobody seemed all that sad to see go. Mostly, it’s one of those things you say before saying something worse about somebody.

This person, who would have known a lot more than I did about what kind of guy Mickey Callaway was, looked at me as if I were the DiamondVision version of Mercury Mets leadoff hitter Rickey Henderson, which is to say like I had a third eye embedded in my forehead. C+C Music Factory had a song for situations of this nature, the one about things that make you go “hmmmm…”

There wasn’t much elaborating to go with the look and I didn’t ask for any. As noted, Callaway was no longer the manager, and, besides, I wasn’t exactly digging for dirt, just taking part in a friendly chat, so I didn’t pursue what this person really thought or what might have been at the root of the reaction. But I left the conversation thinking Mickey Callaway might not have been such a nice guy.

On Monday night, the Athletic reported Callaway “aggressively pursued at least five women who work in sports media, sending three of them inappropriate photographs and asking one of them to send nude photos in return.” It’s pretty damning stuff, extending back to Callaway’s years with Cleveland, threading through his tenure managing the Mets, and continuing in Anaheim. You can read the story by Brittany Ghiroli and Katie Strang here. The Angels, who currently employ Callaway as their pitching coach, said they “will conduct a full investigation with MLB,” which seems like a reasonable immediate next step to announce when a story like this breaks.

It also seems reasonable to admit I have no idea who is or isn’t a nice guy at first or maybe thousandth distant glance, certainly not if I have no first-hand experience with the person in question — even if it’s a person I want to think of as a nice guy mainly because he’s a Mets guy.

When the Mets hire for a high-profile position somebody with whom I have little if any familiarity, I tend to lean to the benefit of the doubt. I read the initial profiles, watch the introductory press availability, pick out the encouraging aspects and write something upbeat. I prefer to think whatever the Mets are doing isn’t a bad idea. Hiring Mickey Callaway seemed like not a bad idea. Hiring Jared Porter seemed like not a bad idea. People presumably in the know spoke highly of both of them. Callaway was said to be a ready-made manager, Porter an ideal GM. Porter is out of baseball — and I would guess Callaway will be soon — because of the things nobody felt secure speaking of publicly.

Porter was the Mets’ problem until they disassociated themselves from him quickly. Callaway is not directly the Mets’ problem in 2021, but it didn’t take Woodward and Bernstein to ascertain that, like Porter, he was hired by Sandy Alderson. We learned in the aftermath of the Porter revelation that “did you ever engage in harassing behavior toward a female reporter?” was not a question that was asked in the hiring process. If it wasn’t asked of Porter in 2020, it likely wasn’t asked of Callaway in 2018. That the subject apparently needs to be broached in baseball — or any field — is incredibly sad. That people trying to do their job have to put up with the kinds of come-ons that Porter and allegedly Callaway considered fair game…well, yeech.

Not nice is an understatement. Consider the benefit of the doubt suspended for the foreseeable future.

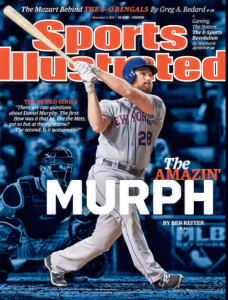

by Greg Prince on 31 January 2021 5:36 pm It’s a summer night in 2008. Utilityman Marlon Anderson has gone on the 15-day DL with a strained hamstring. To replace him, the Mets, in Houston, look to their geographically proximate Triple-A farm club in New Orleans and call up from the Zephyrs infielder/outfielder/hitter Daniel Murphy. His first plate appearance, versus Roy Oswalt, results in a single. Twenty at-bats into his major league career, he’s a .500 hitter. At the end of his abbreviated rookie season, his average is .313. He has played in 26 games at Shea Stadium, all of them with the pressure of a playoff race falling on his inexperienced shoulders. After 2008, Daniel won’t ever play at Shea again and will wait a long time to chase anything resembling a pennant.

The infielder/outfielder/hitter drops one of his identifying descriptors pretty quickly, as quickly as he drops a fly ball in left. The glove of Daniel Murphy — “Murph” to us, even if you’d think such common shortening was permanently proprietary to legendary announcer Bob Murphy — is confined to the infield as 2009 gets rolling. He’s not really a natural there, either. What Murph does is hit. Not .500; not .313; not enough to forgive his shaky fielding and iffy instincts when he’s a sophomore, but he settles in. Citi Field is new. Few can swat homers over its comically far and tall walls. Murph leads the Mets in dingers with a dozen.

If he’s not gonna be our third baseman (we have David) and he’s not gonna be our first baseman (we’ll have Ike), Murph has to be something. He played a little second at Binghamton. He’ll play a little more at Buffalo in 2010. Get the hang of the position and come back to the bigs. Except he gets wiped out by an opposing baserunner and what was going to be his third year is wiped out with him. But an idea has been hatched and, come 2011 (after the incredibly ill-advised Brad Emaus experiment implodes on contact), Murph is indeed the Mets second baseman of the present. Sometimes. He plays everywhere on the infield as needed. David Wright misses time. Ike Davis misses more time. Murphy’s a third baseman some days and a first baseman others. One Sunday when he’s a second baseman, he takes a spike to the knee and finds another season prematurely ended. Double plays have become double jeopardy. Before 2011’s over, however, Murph’s hitting .320 on August 7.

Once recovered, the Golden Age of Murph is at hand. For three seasons, Daniel plays almost every day, usually at second. Tim Teufel works him into a state of defensive adequacy. Murphy plays on the edge of the grass, where it’s safest, as with training wheels. When nobody’s looking, he steals bases, successful on 46 of 56 attempts from 2012 to 2014. Sometimes he gets himself thrown out running any which way but wise. But he keeps hitting, to a composite tune of .288. In 2013, he’s the only Met position player to not miss time and finishes second in the National League in hits. In 2014, he alone represents the Mets at the All-Star Game. Is Daniel Murphy a star? Not really, but there isn’t much glitter to these perennially languishing Mets. They win 74, 74 and 79 games. Somebody has to hold our interest when the more fascinating among the Met pitchers are idle. It’s the ability to keep us going that makes this Murph’s Golden Age.

Most Valuable Murph. Then comes 2015, with its autumn nights in particular. The Mets are still playing, having captured the division title they missed when Murph was a rookie and Shea was condemned to the wreckers. He’s had a good year. He’s about to have an epic postseason. He and the pitchers defeat the Dodgers. He and his sweet lefty power stroke combine to crush the Cubs. Don’t let Murph hear you say that, though. In every postgame interview session — where Murphy’s presence is dictated by his in-game performance — he namechecks 24 teammates before he mentions any of his seven homers, including the six he bashed in consecutive NLDS and NLCS games. He’s humble. He’s real. He was real in Spring Training, too, when he kind of put his foot in his mouth (something about “lifestyle”), but you couldn’t say he wasn’t being his version of real then as well.

It’s also the real Murph who appears in the World Series, the one who was never extraordinarily comfortable at any position other than hitter. Since 2008 he’s made some crazy good plays wherever he’s been asked to station himself, but the routine ones have had a tendency to bedevil him. One in particular, a grounder in Game Four, contributes directly to a win becoming a loss. Just about everybody on the Mets contributes across five games to a potential world championship transforming into a “nice try, fellas.” Murph the NLCS MVP doesn’t register as remotely valuable versus Kansas City. Except for the crowds, it might as well be some night at Citi Field in the depths of 2013. Like Ray Knight and Mike Hampton, Daniel doesn’t play a single regular-season Mets game after winning individual postseason honors. Earning a trophy for yourself in October seems to be the quickest ticket out of Flushing.

As a Washington National in 2016 and 2017, Murph becomes Ryne Sandberg against everybody and Stan Musial against the Mets. It might not have been the worst idea to let him walk. It becomes the worst actuality, but back on that night in 2008 when the Mets simply need to replace Marlon Anderson, who would guess the 23-year-old minor league callup without an obvious position is going to help define an entire era of Mets baseball? He is going to embody the blah years and personify a joyous if transitory vault into the stratosphere. He is going to be Murph of the Mets, and when he announces, at the age of 35, that he’s retiring ahead of the 2021 season, we’ll put aside his stints with the Nationals, the Cubs and the Rockies and recall him primarily as Murph of the Mets. He was ours. He still is.

Daniel Murphy goes down as the last active position player who played for the Mets at Shea Stadium; two relievers endure as major leaguers as the next Spring Training approaches. Joe Smith, who dates to 2007, is still an Astro. Ollie Perez, veteran of 2006, is still a free agent, but maintains the ability to throw with his left arm, so he’s probably good to go for the year ahead. Shea’s long gone. The first generation of Citi Field Mets have commenced their collective fade into memory. The Longest Ago Met Still Active who didn’t play at Shea is Justin Turner. LAMSAs keep coming from later.

Murph keeps speaking well of his Met teammates. In discussing his decision to stop playing — having become a player of enough stature to “retire” rather than just not get an offer — he remembers the company of others rather than his own accomplishments. To SNY’s Andy Martino, he says of deGrom and Duda, Familia and Lagares, Tejada and Flores, “We all grew up together. We did life together,” a quintessentially Murph framing of rising and eventually succeeding as a Metropolitan. Those are your 2015 National League champions. They, too, grow temporally distant. That happens in baseball.

So does, if you’re lucky, the occasional Murph, someone whom a stubbornly engaged fan might notice, amid the persistent mediocrity his team churns out, making himself over “from sub to grinder to hero…continu[ing] to sandwich base hits”. You could do worse than to order the Daniel Murphy, side of fundamentals angst notwithstanding. As a hitter, he was one of the best at his position. As a Met, he is one of the characters you don’t forget.

Greetings from the Mets to a Met. I joined Mike Silva’s Talkin’ Mets podcast to delve a little more into Murph. You can listen here (I come on around the 26:00 mark).

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2021 4:53 pm We need not mourn the departure of Long Island’s Own Steven Matz, traded to Toronto for younger pitchers Sean Reid-Foley, Yennsy Diaz and Josh Winckowski on Wednesday night. Nor need we celebrate his deletion from Met ranks. Sending Steven packing was just something that needed to be done.

Still, Matz, soon to turn 30, was no ordinary lefty coming off an 0-5, 9.68 ERA shortened season. He was one of us, from around here, having grown up with an affinity for the team we love before he ever pitched in its uniform. Steven couldn’t have started stronger, just as he couldn’t have ended worse. In between, he settled in as a familiar if ultimately frustrating figure. We wanted him to pick up where he left off on June 28, 2015, the first time we made his acquaintance. After seven-and-two-thirds innings we were standing in tribute to his maiden major league voyage and showering him with grateful applause. We’d done that multiple times that fun Sunday as he was not only defeating the Reds from the mound, but beating them silly with his bat.

When you get to the Blue Jays, Steven, maybe don’t set your bar so high.

LIOSM couldn’t follow up his first appearance with many remotely as scintillating, but I found his Met presence over time comforting. He was one of the last remaining 2015 National League champions. He was, in case you hadn’t heard, a local product. He was never unpleasant to listen to after games, lose or win. He supported causes it wouldn’t occur to you to oppose. There’s something to be said for your team having a foundation of players who are always there, who you don’t have to get used to, who you have absolutely nothing against when he’s not contributing to another defeat.

I liked Steven Matz a lot, albeit not enough to want him here forever. Not after 2020. Maybe not after six seasons that ceased amounting to much. Peering ahead to 2021 when I began mentally constructing April rotations — deGrom, Stroman, Carrasco, Peterson, maybe this Lucchesi fellow from San Diego — I realized I was already forgetting Matz before he was gone. That’s not a good sign for continued longevity.

All told, we probably got just the right amount of the lefty. Six years is plenty. Throwing key innings en route to a pennant was enormous. Occasional bursts of brilliance reminding you that maybe he will live up to the potential we projected for him presented an adequate case for preserving his parking space. Steven was a made Met for a while, intrinsic to the starting five we idealized in the middle of the 2010s. We’re the Mets. We grow pitchers. We grew or at least nurtured, in order of their debuts, Matt Harvey, Zack Wheeler, Jacob deGrom, Noah Syndergaard and Steven Matz. By the time we gathered them together on one active roster for consecutive outings, the dream dissipated before our eyes.

Harvey, first up in 2012, was altogether done as a Met by 2018. Wheeler couldn’t help himself from taking the money and running to Philadelphia after 2019. Syndergaard’s elbow isn’t yet out of the shop from 2020 Tommy John surgery. Matz? Seemed dependable more than he could actually be depended upon, but nobody ever said the theoretical Five Aces were created equal.

Jacob deGrom’s still pretty good, however.

My one fear as extremely sympathetic Steven Matz scuffled was I would come to turn on him as I did on his inconsistent southpaw predecessor in Met clothing, Jon Niese. They are the only two fully homegrown lefthanders to start more than a hundred games for the Mets over the past four decades. For a while there, Niese was foundational, too. To be fair, I didn’t necessarily diminish my simpatico for Jon, because I was never particularly attached to him to begin with. Also to be fair, Niese was never really framed in golden terms — anybody really salivate at the notion of Niese, Pelfrey and Gee anchoring our future? — so you couldn’t honestly grow overly indignant when he proved to be mostly middling. He showed up one day, seemed kind of OK some days, got paid to get better and, well, didn’t.

It’s hard to remember that Jon Niese was a 2015 Met, just like most of the Aces. He started 29 games that championship season — as many as Harvey, one fewer than deGrom and nearly two-dozen more than Matz. I found it surprising that Niese and Bartolo Colon (a staff-leading 31 starts) were shunted aside to long relief that September to assure that the Mets’ postseason rotation would be all about the kids. By then, despite yeoman service dating to the last days of Shea, I was done with Niese. He was Toby Flenderson to my Michael Scott and I just wanted him to stop being the way that he was.

When I wished to express my dismay with lefty Matz, I would compare him, either in print or in my head, to lefty Niese. Now you don’t want to me referring to you as STEVEATHON, do you? Niese started 179 games as a Met and compiled an ERA a tick below 4. Matz gave us 107 starts and an ERA of 4.35. So maybe Matz actually wasn’t as good as Niese, yet my fear never came to fruition. I never turned on Matz. Yet I haven’t wrapped a black armband around any of the sleeves on my 2015 commemorative t-shirts.

Matz’s final appearance as a Met came in relief on the last day of last season. He pitched three innings, gave up three earned runs and lowered his earned run average as a result. Think about that: you give up a run every inning and it technically qualifies as one of your better days.

Those are the days that need to end, my friend. Or be taken to Toronto the minute border restrictions are lifted. Thank you for the first day, Steven, and scattered nights along the way. When you come by again, we’ll stand and applaud from wherever we are.

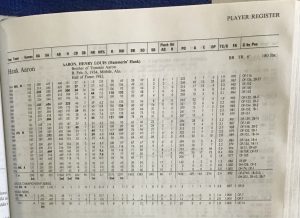

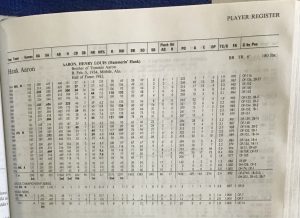

by Greg Prince on 22 January 2021 2:41 pm Tom Seaver idolized Hank Aaron — “my hero in baseball from the time I was old enough to recognize talent.” Why would the future best pitcher in baseball gravitate to a hitter? “It must have been his form that made me pick him,” Tom wrote (with Dick Schaap) in The Perfect Game. “He seemed so graceful, such a complete professional. You could see the power in him, the strength in his hands and wrists. I sat through entire ballgames, just looking at Henry Aaron, nothing else, fascinated by him, studying him at the plate and on the bases and in the field.”

That was one of the first biographical notes I learned about Tom Seaver, whom I idolized. I guess that made Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves my grandidol. If he was grand enough for Seaver, that was good enough for me. Except I didn’t really need Tom Seaver’s blessing to admire the hell out of Hank Aaron. I was a kid who fell in love with baseball as the 1960s turned to the 1970s. Hank Aaron stood at the sport’s pinnacle. If you loved baseball, I don’t know how you couldn’t have revered Hank Aaron.

Idols all (illustration by Warren Zvon). Or Henry Aaron. I learned because of Hank Aaron that “Hank” was short for “Henry”. Hammerin’ Hank. Bad Henry. Both fit, as did his last name: Aaron, first in your Baseball Encyclopedia for as long as you relied on the Baseball Encyclopedia when you wanted to look up baseball information…and where else were you gonna look up baseball information in most of the latter portion of the twentieth century? Alas, Henry Aaron’s been surpassed alphabetically in the twenty-first, just as the Baseball Encyclopedia has been technologically, so now he comes in behind David Aardsma when you visit retrosheet.org.

He was surpassed in number of career home runs, too, but rather than serving to diminish his standing, Barry Bonds blasting a few more homers than Aaron only enhanced the status of the man listed as runner-up since the summer of 2007. Hank/Henry looks just as impressive in the Internet age as he did when we relied on the backs of baseball cards and the screens of portable black & white televisions for our glimpses of greatness. When some other medium comes along that allows us to absorb performance and persona, Aaron will still be right there at the top.

Hank Aaron died today at the age of 86. Baseball Hall of Famers have died at an alarming rate of late. Seven last year, including Seaver (Aaron’s selection for “the toughest pitcher I ever had to face”). Three here in January. Tommy Lasorda the celebrity manager early in the month. Don Sutton the doggedly competitive pitcher early in the week. And now Henry Louis Aaron, as magnificent a baseball player and monumental a baseball person as has ever lived.

If one of the inner-circle superstars of the sport could be said to have snuck up on his crowning statistical glory, it was Aaron. Before he was one of the absolute greatest, he was one of the absolute greats. Hank Aaron kept a pied-à-terre on league leader cards. His summer vacations had to be deferred because he was inevitably needed at the All-Star Game. It was all very excellent and relatively quiet. For a dozen years his campaigns had been conducted in Milwaukee, where there were two World Series and an MVP award in the ’50s and moving vans lined up at County Stadium by the end of 1965. Then it was off to Atlanta. Aaron’s Braves enjoyed one brief moment in the sun down south: the 1969 NLCS.

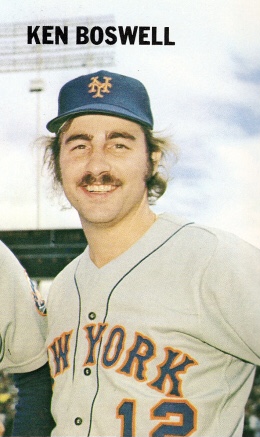

Forgive us if we don’t mind that he and his Western Division champion teammates didn’t make the World Series that year. Hank had to settle for a home run in each game of the Mets’ three-oh sweep. Given what Aaron did to Mets pitching as a matter of course — 45 regular-season home runs overall, including one that he launched into the distant center field bleachers of the Polo Grounds — it wasn’t surprising that he took Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry deep on consecutive days. Hank batted .357 in his final playoff appearance, including a Game Three double that spurred Ken Boswell to request a small favor when Aaron pulled into second base.

“Henry, we’re trying to win this thing. Let up on us, will you?”

Apologies to David Aardsma, but there’s only one player who should lead off the Baseball Encyclopedia. Methodically, he moved up myriad rankings to a point where attention had to be paid to the low-key right fielder from Alabama. No fewer than 120 games played each of his first 20 years. More hits and runs upon retirement than anybody other than Ty Cobb. More runs batted in than anybody to this day. And that home run record, the one Hank wristed his way to via consistency even the most finely tuned machinery would envy. From his second season through the eighteen that followed, Hank never produced more than 47 homers, but he never delivered fewer than 24. He passed 500 when hardly anybody belted 500. As he approached 600, he trailed only Babe Ruth and Willie Mays. Mays ran out of steam and, with Willie in a Mets uniform, Aaron passed him. Without flash, Hammerin’ Hank was on his way to matching the legendary Bambino.

Why this didn’t sit well with every living, breathing American mystified me as a kid. I thought it was the greatest thing to ever happen to baseball, 1969 Mets included. Nobody was ever gonna pass Babe Ruth’s 714, except now somebody was. Who wouldn’t root to witness uplifting history of this sort?

The worst elements of our society, apparently, the ones who wrote him threatening letters because Hank committed the imagined crime of slugging while Black. I wasn’t naïve; I knew there was such a thing as racial prejudice when I was eleven years old. I knew that if Hank had been born a little sooner he wouldn’t have had the opportunity to have taken his talents from the Indianapolis Clowns to the Boston Braves organization. I knew the promotion of Jackie Robinson, who was fifteen years older than Aaron but debuted in Brooklyn only seven years before Hank was called up to Milwaukee, hadn’t solved everything. Yet I wouldn’t have dreamed mindless, hateful prejudice would extend to beloved baseball idol Henry Aaron on the precipice of heretofore unimaginable achievement. This was 1974, not 1947. I wouldn’t have dreamed a lot of awful dreams when I was young.

No. 1, according to Topps. Sounds right. Hank Aaron finished 1973 with 713 home runs, one shy of Ruth. There was no way he was gonna not hit his 714th and 715th as soon as the next season started. Topps knew it and threw him a coronation ahead of time. Card No. 1 dispensed with the standard niceties and dubbed him the NEW ALL-TIME HOME RUN KING right on the front. The five cards that followed encompassed reproductions of every Aaron issue covering his preceding 20 seasons in the big leagues. Topps didn’t do anything like this for anybody else. You didn’t need a Baseball Encyclopedia to understand Hank Aaron’s pending accomplishment was bigger than the game itself.

Ruth was tied on Opening Day. Four nights later, he was passed. Babe Ruth was still Babe Ruth. But Henry Aaron was now every bit as transcendent. He was an American idol. I don’t know that all of America deserved him, but the vast majority of us applauded fervently. What a privilege to be a kid watching Hank Aaron ascend as he did. He added forty home runs over the rest of his career — the final two seasons of it back in Milwaukee as a Brewer — and left us the legacy of 755. It’s not the most home runs anybody ever hit in the major leagues. But it is, like Hank Aaron, the grandest of baseball figures.

by Greg Prince on 19 January 2021 12:37 pm A friend suggests “LFGM” now stands for Let’s Find a General Manager. Implicit therein is let’s find a general manager who isn’t as apparently icky as the Mets GM whose stay in the job was brief and whose sudden dismissal from it became fait accompli once certain absolutely damning facts came to light.

On Monday night, ESPN reported that in 2016, Jared Porter, then working in the Cubs front office, had sent a barrage of harassing, explicit texts (lewd photos included) to a female reporter from outside the US attempting to cover baseball, a.k.a. do her job. According to the story by Mina Kimes and Jeff Passan, the reporter left sports media in part because of Porter’s actions. While she tried to cover the game, she felt it necessary to avoid the man who was disturbingly slow to take a hint and leave her be. “I started to ask myself, ‘Why do I have to put myself through these situations to earn a living?’” the now former journalist explained.

Porter confirmed his actions to ESPN, which had been putting together a story about the texts as far back as 2017 but relented in deference to Porter’s target’s concern that “her career would be harmed if the story emerged”. Porter’s career as Mets GM ended within twelve hours of ESPN’s report. This morning Steve Cohen tweeted the executive brought on board in December had just been “terminated,” citing “the importance of integrity” and emphasizing “zero tolerance for this type of behavior”.

What the Mets lacked in vetting when they hired the highly recommended Porter they made up for in decisiveness when they let him go…not that there was much of a decision to be made. What Porter copped to doing was disgusting and, given his own admission, not in dispute. Clever baseball mind or not, you can’t present him to the public as one of the faces of your organization. You certainly can’t implicitly sanction what he did by keeping him around.

Who will be the next general manager? Somebody who doesn’t do stuff like this would be a good baseline qualification.

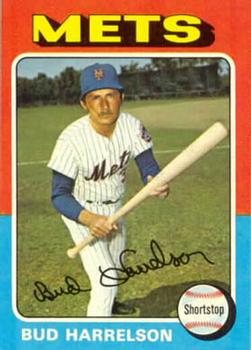

by Greg Prince on 11 January 2021 7:26 pm It’s a world that could use Francisco Lindor, a guy called Mr. Smile. It’s a world that could use a reason to smile. From our parochial perspective, it’s a world that could use Mr. Smile ceremonially slipping into Mets jersey No. 12 and smiling like crazy as flashes pop inside whichever title-sponsored club remains as a relic of the Wilponian vision that built Citi Field. Those photo ops don’t always augur well for the players who grip and grin — it didn’t work for Roberto Alomar in the season-and-a-half he wore Mets jersey No. 12 — but they sure do warm a winter’s day.

We’ll settle instead for the Francisco Lindor closeup we got via Zoom on Monday, January 11. He sat behind a desk in his home and wore a Mets cap. He spoke enthusiastically about being a Met in the tradition of Beltran, Delgado, Reyes, Wright and his idol Alomar, whose Cleveland rather than New York on-field performance Lindor would be wise to continue to emulate. Every time the native Puerto Rican was told “welcome to New York” — reporters graciously serving as de facto goodwill ambassadors — he expressed thanks and maintained his smile. He didn’t dare anybody to knock the smile off his face à la Bobby Bonilla when he zoomed into our lives in December of 1991. Lindor also didn’t commit to being a Met beyond 2021, but he’s gonna be a Met during 2021, which is something that until last week we had little idea would be a fact.

Lindor happily inserted himself (and his idol) into the big picture of Mets history. We had little idea until last week about a number of facts in this country. We could have had we intently paid attention or been willing to comprehend what was being planned out in the open, but even after 2020, we entered 2021 as brightsiders. Last year was the worst. This year will be better.

The Mets announced they’d traded for Lindor on Thursday, January 7. On Wednesday, January 6, the U.S. Capitol was overrun by domestic terrorists. Like the Mets’ press briefing, the violence was visible on television. Some of the violence. We’ve seen loads more evidence of it after the fact. What we saw on January 6, as Congress met to certify the election of Joe Biden as the next president of the United States — something that had been confirmed beyond any reasonable statistical doubt again and again over the preceding two months— was enough to let you know you were seeing something unprecedented in our lifetimes. It was horrifying. Mobs of terrorists breaking through windows and doors and coming for lawmakers that they’d whipped themselves into believing the worst about. It was more horrifying because the current president, the one who lost the election, let the mob of terrorists know, out in the open, that terrorizing the legislative branch as a mob bore his seal of approval.

The Mets trading for Lindor on January 7 was a big baseball deal. And rather insignificant in the scheme of the America we lived through on January 6. But if this country can do anything, it’s compartmentalize. Still, Daily News columnist Bradford William Davis took a moment out of the ritual peppering of Sandy Alderson and Jared Porter with baseball questions on January 7 to wonder aloud what Alderson had to say about January 6.

“It’s not within the scope of this press conference,” Alderson replied, but he agreed that it was “a question that needs to be answered.” The Mets’ president said he found the terrorist attack on the Capitol “to be disturbing on many different levels, and I’m sure most people did.” The United States Marine Corps veteran continued:

As somebody like myself who spent a few years defending democracy, I guess in some way, not just yesterday but the last few years have been extraordinarily disappointing. But we have institutions that protect us from individuals in most cases, and it seems that those institutions have not only survived but guaranteed our survival as a democracy. So that’s my view.

It wasn’t much of a detour from the baseball talk, but as Sandy (and Bradford) indicated, the actions of January 6 didn’t constitute something you could put out four fingers for and let pass.

Maybe eventually this year will be better. Maybe after we hold our breath and hope hard. Maybe by being vigilant as hell. If we’re lucky, we’ll get to the other side and Mr. Smile will be there to welcome us. Maybe we’ll even be able to greet him relatively up close as fans customarily do.

This world and this country have a ways to go. So does this franchise, but the franchise has gotten a lot closer to where we want it to be. It’s gotten Francisco Lindor, not to mention Carlos Carrasco. That’s a lot of ways to have traversed on any day in January. The ways that’s left to go is to be named later, as soon as it’s acquired. The Mets in the first months of Steve Cohen and the second coming of Sandy Alderson warn us they’re not prepared to spend like drunken sailors.

How about soaking up the tab like sober yachtsmen?

For now, shortstop is solved. There’s a starting catcher who can catch. The middle of the rotation and bullpen have been bolstered. Other spots need to be strengthened. More pitching. A legit center fielder. High-end infield tinkering. Set sail, Steve and Sandy. Send the word across the high seas of free agency and to other sellers. We want you. We want you. We want you as a new recruit.

Necessarily tossed overboard in the general direction of Lake Erie were two members in good standing of the SS Mets, two Mets SSes. One was the future not very long ago. One was the future literally last week. Today they are ex-Mets. You make this trade seven days out of every seven, Amed Rosario and Andrés Giménez plus minor leaguers Isaiah Green and Josh Wolf for Lindor and Carrasco, but you don’t do it without an ounce of sentimental regret. I’ll miss Rosario and Giménez like I missed Neil Allen, Hubie Brooks and the package of potential and heritage represented by Preston Wilson (Mookie’s lad). I felt bad that they were no longer Mets. I felt great that Keith Hernandez, Gary Carter and Mike Piazza arrived because they departed.

Which is to say I got over their respective departures.

The same figures to be true once Mr. Smile flashes his grin after doing something more spectacular than say hello or the pitcher called Cookie makes opposing hitters crumble. Still, I was just getting accustomed to having my breath taken away by young Giménez and we’re not so deep into 2021 that I can’t remember the summers of 2017 — when we anxiously awaited the promotion of young Rosario — and 2019 — when Amed was among the kids making the Mets lovable and contenders. If everything went great for both of them, you could imagine either of them growing up to become our very own version of Francisco Lindor.

Or, you know, we could cut out the middleman and get the middle infielder they were trying to be. Andrés is 22. Amed is 25. Francisco is 27, might stick around and brought a pitcher with him. Maybe this year will be better than the last.

by Jason Fry on 8 January 2021 6:41 pm You remember where you were for the truly big trades that reorder a franchise, the ones that you know are lines between before and after.

The winter day when I saw in the newspaper that Gary Carter, the ebullient yet tough-as-nails All-Star catcher for the Montreal Expos, was coming to the Mets.

The summer afternoon spent eyeing the wire feed in my office until the cascade of rumor turned into a single, amazing fact: Preternaturally gifted slugger and pop-culture icon Mike Piazza had been sprung from his brief captivity in Miami and was on his way to Flushing.

The night I was walking around with friends at a bachelor party in Las Vegas and spied on a betting parlor’s TV that Johan Santana, the Twins’ Cy Young winner and indomitable leader, would indeed be a Met.

And, of course, the frenzied afternoon/evening of bombardment via Twitter and sports radio and SNY and probably random planes equipped for skywriting that the Mets had somehow fallen backwards out of a deal for Carlos Gomez and into one for the Tigers’ monstrous destroyer of baseballs, Yoenis Cespedes.

Each time, what I remember most is the happy sense of satisfaction and how it immediately had to make room for anticipation: They’re going for it. Oh this is gonna be fun.

The Mets — you’ve probably heard — struck a deal with the Indians for Francisco Lindor and Carlos Carrasco, sending back Andres Gimenez, Amed Rosario and a pair of lottery tickets from the low minors in Josh Wolf and Isaiah Greene. Carrasco — 2020’s Comeback Player of the Year after battling leukemia — will slot in behind Jacob deGrom and Marcus Stroman in a rotation that badly needed upgrades. And Lindor? Well, he’s only one of the best players in the sport, electric on offense and defense and the kind of guy who lights up highlight reels, scoreboards and social-media feeds with his joy for the game. And he’s only 27!

Cleveland is heartbroken, and I feel for fans of the team that will soon no longer be the Indians — their franchise hasn’t celebrated a title since 1948, and they’re in a weak division that certainly seemed within their reach. The current team is being torn down despite its owner — Larry Dolan, uncle of the thoroughly loathsome James — being worth $600 million.

That’s a disgrace, plain and simple.

But it’s also baseball. And we’re all too familiar with such disgraces. We’ve just been sprung from the dungeon of Wilpon ownership, freed from their daily displays of dishonesty, incompetence, interference, nepotism, paranoia and stupidity. If you live in Cleveland and you’ve ever teared up at a video of shocked animals tentatively exploring impossibly soft grass after being sprung from puppy mills or factory farms, well, that’s our fanbase right now. Sorry, Cleveland. It shouldn’t be this way, for any of us, but since we can’t change the rules, let us have this. Goodness knows we’ve done our time.

So we promise to take good care of Lindor, hopefully after a contract extension to ensure he’ll stay for a long time. We’ll embrace Cookie. And we’ll wish the best for Gimenez and Rosario. I know it’s no consolation, but you’re going to appreciate Gimenez’s instincts for the game, nodding at how he’s always in the right place on the field and wondering how he just seems to know how to do that. Be patient with Rosario and you may find yourself — as we did at intervals — enjoying a slash-and-burn hitter who makes everybody’s tempo a little quicker. Here’s hoping they’re part of the team that rises in the place of the one being dismantled, and that it’s soon.

The Lindor-Carrasco news came in an awful hurry, moving startlingly quickly from one report to two and then three and then a couple of iterations of the personnel involved and then to a WELCOME TO NEW YORK graphic complete with Photoshopped new Mets. (Among other things, the Steve Cohen regime is so far pretty watertight as far as leaks.) And it arrived as a lot of us were cooped up in front of our computers, trapped by the pandemic and winter and profound worries about our country.

Under those circumstances, I would have been grateful for the distraction of a waiver-wire deal for a potentially still canny pinch-hitter or an nonroster invitation to camp for some lefty reliever who looked good as a minor leaguer a few years ago. But this? This was just a little different.

This was the arrival of a high-wattage star who’ll look perfect in Mets pinstripes, whether he’s going into the hole for a grounder or flying around second with his eye on more — and a big piece of the answer to the pesky question of who’s going to pitch. And this was the formal acknowledgment that things really are different — that we no longer have to grouse about the scratch-and-dent aisle, or nickels in the couch, or parse disingenuous garbage from serial liars in search of hints of a plan, despite our suspicion that there isn’t one.

The Mets are going for it. Oh this is gonna be fun.

by Greg Prince on 6 January 2021 9:02 pm

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2020 3:05 pm When the planes hit the Twin Towers, as far as I know, none of the phone calls from the people on board were messages of hate or revenge — they were all messages of love.

—David, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Love, Actually

Today I turn the age Jenrry Mejia was wearing when he was suspended from baseball for life after testing positive for ingestion of performance-enhancing substances. Jenrry’s still alive and he’s no longer suspended from baseball, so maybe there’s hope for us all.

Ol’ No. 58. I can relate. (Image by The 7 Line.) We shall expel 2020 from the present in a matter of hours. Our collective problems will not magically disappear, but we can pretend at least for a couple of days that a new year can alter the course of time. Dick Clark built an additional wing onto his empire by appealing to such Rockin’ Eve thinking.

With the last day of 2020, the one of which I feel most proprietary on an annual basis, I wish to offer a little co-director’s commentary regarding thirty people whose times and lives I also grew a little proprietary about in recent months. Those would be My Guys, as I came to think of them: the subjects of my A Met for All Seasons essays.

You know the series. Gosh, I hope you do. Jason and I offered it up twice a week for thirty weeks, from sometime in April to sometime in November, partly because we’d mulled doing something like it for about nine years, more because in April there was no baseball to write about from a fierce urgency of now standpoint. Looking back was all we could do. I’m comfortable with that direction. When you reach the age reflected on Jenrry Mejia’s most recent Mets uniform top, hindsight beats 2020.

I spent seven months thinking about My Guys. I’ve continued to think about My Guys. I haven’t been out much, so I haven’t had much opportunity to talk about them out loud. It’s my birthday. Indulge me for another thirty paragraphs, would you?

***My first guy and the first we presented overall, on April 21, was Rico Brogna, representing 1994. Rico was the AMFAS pilot episode in my mind, one I kind of had in the can. I’ve been telling what I think of as my Rico Brogna story since the 1994-95 strike, and it seemed uncommonly pertinent to the present day. He was the midsummer revelation of a year that suddenly stopped and left me wondering when baseball would be back, specifically because I had one thing to look forward to: the return of Rico Brogna. My first recurring theme was embodied by that first AMFAS season as well. I’m fond of the less-remembered Met years and bringing to light what was considered a relatively big deal in its time. “Less remembered” is not to be confused with forgotten (which I don’t think any Met ever is completely) or shall we say obscure (which is more Jason’s beat than mine).

Donn Clendenon, on May 1, came with an agenda. My agenda, that is. I wished to poke a hole in a phrase that had come to bug me. “Without so-and-so, such-and-such never would have happened.” It bugged me because why do we assume we had to do “without” so-and-so? I realize it’s a term of appreciation and acknowledgement, but after a while, it struck me as an unnecessary tic. In 1969, we were with Donn Clendenon. That’s what mattered. His impact on 1969 mattered. His whole life mattered as well, and it was pretty substantial, but I made a conscious decision to not retell it when others had told it more deeply. I was inevitably more about the Season than I was the Met.

Willie Mays, on May 5, was another agenda item, sort of. I had tired of the reflex social media reaction to pictures of players in uniforms with which they are not universally associated. Willie Mays is the subject of a lot of that ironic “legend” stuff, as in “Mets legend Willie Mays,” it’s funny because he was mostly a Giant and, besides, he was old when he ended his career as a Met in 1973 (though sixteen years younger than I am now, and I’m just a kid). I’ve always been defensive on Willie Mays’s Mets behalf, as if claiming perhaps the greatest ballplayer ever as one of your own requires a brief. Also, May 5 was one day before Willie’s birthday, and I’m not beyond a cheap calendar-driven hook.

Al Leiter, on May 15, represented my first challenge. I had him for 2002, which was a mostly crappy year. Al wasn’t crappy in 2002, but it wasn’t exactly “his” year. So I thought about Al Leiter in 2002, and the first thing I thought of was him starting on Opening Day that year and me being there and being satisfied that he and I were together, which led me to check my notes and confirm Al had started with me at a game more than any Met pitcher had. Satisfaction wasn’t guaranteed, but I rarely left Shea disgusted.

Ah, Melvin Mora, May 19, the 2000 entrant. I say “ah,” because nobody left a comment, which tells me either nobody cared or I did a less than compelling job of making people care. Ah, whaddaya gonna do? Melvin occupies a very specific moment in time for the Mets. He was here for two seasons, yet not at the beginning of his first nor the end of his second. They happened to be two of the most momentous seasons in modern Met times: 1999 and 2000. Melvin played a pivotal role late in the first of his seasons and was sent away before he could do more in he second of them. I fell in love with him in the interim, yet didn’t really mourn his departure. We needed a shortstop, and Melvin, who could do it all, couldn’t really play short. Thus, Melvin Mora for Mike Bordick. Which led to a whole other thing I couldn’t get behind: hating the trade that brought us Mike Bordick because Bordick was here, not monumentally effective, then gone, while Mora thrived in Baltimore. As the series went on, I came to hate hating trades. It’s too easy and ultimately pointless to be pissed off all the time.

R.A. Dickey, on May 29, was my first AMFAS from the FAFIF era (so many acronyms!). Anybody I’d already written about a lot as he was being a Met was going to take some thinking. I didn’t want to fully recycle the Best of Dickey or whatever from 2010 to 2012 (his last season was his essay season). I wanted to provide fresh takes by doing this stuff. I split the difference for R.A., repurposing a few lines here and there to celebrate the way the knuckleballer made the language dance. That was what attracted me to R.A. ten years earlier.

Johan Santana, June 2, was, to me, something of a copout. I didn’t tell you anything I hadn’t already told you about the man whose uniform number my age was repping until midnight last night. I tried to do it a little differently than I had before, peeling layer by layer the onion that was Johan’s finest 2008 hour, his last start and our last win at Shea, but I was doing Johan on June 2 for one reason: because I couldn’t get otherwise interested in writing about the Mets during the George Floyd protests. I had planned to do Pedro Martinez on that day, but little seemed more irrelevant than thousands of words on a retired pitcher who did whatever whenever while America was trying to figure itself out in the present. The calendar reminded me we had just passed the anniversary of Johan’s no-hitter, and, like I said, I’m not beyond a cheap hook. I think what I wrote was fine, but my heart was not in the exercise that day.

Lenny Randle, June 12, was the manifestation of a determination I’d made during the preceding offseason that there was something to like about every Mets season, even the seasons we instantly dismiss or smolderingly detest. Lenny’s big year was 1977. I liked that he joined our ranks and flourished and gave me something to root for. I can’t just spit at seasons and eras. There are too many microclimates. Cloudy with a chance of Randle is sometimes all there is to enjoy. Enjoy it, I figure.

Jason Isringhausen, June 16, sort of picked up on the Randle theme in that for nearly a quarter-of-a-century you can’t mention Isringhausen and his running mates of popular imagination Bill Pulsipher and Paul Wilson without eliciting groans from Mets fans. I think when I began to write about Izzy and 1995, my headspace overlapped with the dismay that Generation K didn’t pan out. But as I got into the story, I found myself grateful for what Izzy (and Pulse) gave us in ’95. They gave us hope. We didn’t know that they wouldn’t engender a whole lot of it down the line. It was just a great scintilla of time to be a Mets fan, that hour when you’re sure something is about to get better. I doubt I’d convince too many people that it’s OK to be happy for what there was rather than rueful for what there wasn’t, but I was happy basking anew in the glow of young Izzy and all that seemed to be transpiring around him. Writing this essay was a turning point of sorts for me as a fan. My cup measured as half-full.

Mookie Wilson, on June 26, became the second of My Guys to bump Pedro Martinez. The schedule for better-late-than-never 2020 had just been issued. It was gonna be a short season, almost as short as the last time baseball jury-rigged itself in miniature, the second half of 1981. The terrain was ideal to go back to that split season and the biggest swing Mookie ever took…until five years later. Before 2020, I had a real soft spot for the less-remembered Met exploits of the shortened seasons. 1981. 1994. 1995. My cup’s not nearly as half-full for 2020.

Craig Swan, on June 30, got to be 1978’s AMFAS because he won the ERA title when few Mets were winning anything. Because of the ERA title, I’ve carried an image of Swan as one of the best pitchers the Mets have ever had. Was he? Define “best” and “ever” narrowly, and absolutely. He was definitely around a long time and I got a kick out of exploring a Met I hadn’t thought that much about over the preceding 36 years.

Now, on July 10, Pedro Martinez was ready for his closeup. The longer he waited, the longer his essay grew. I’d been wanting to do right by Pedro every fall for the preceding decade, because every fall in presenting the Most Valuable Met winner, I’d list the previous winners — just like the papers would when awards were announced — and I’d be reminded I’d long ago given Pedro one lousy paragraph for his sublime 2005. This is an example of me not getting out much even in non-pandemics because, yeah, I really thought about this. Pedro had kind of a Swan vibe to me; to truly get what he meant at his Met peak, you had to have lived it. I hope what I wrote got that across.

Tommie Agee, on July 14, was essentially written by a seven-year-old, as told to a 57-year-old. I sometimes ghost for others in my day job, so why not ghost for my younger self? The best way for me to present Agee to you was how I processed him in 1970. Plus some later stuff. Call it a collaboration between me at seven and me fifty years later.

Jacob deGrom, on July 24, became the easiest scheduling decision of the series for me. He was pitching on July 24. Ohmigod, somebody was pitching on a day in 2020! In practical terms, the coming of belated Opening Day meant fitting AMFAS around our game stories. I have to admit I felt the Mets of “now” were getting in the way of the Mets of “then,” but I guess it was good to have baseball back. Writing about Jacob deGrom, as I’d been doing since 2014 (his year in our spotlight), wasn’t much of a chore. There wasn’t a whole lot new to say, and I didn’t pretend to try to find a novel truth. It’s always a good day to write about Jacob deGrom. And an even better day to watch him pitch.

Darryl Strawberry, on July 28, is where time came to matter most to me in this series. My season of choice was 1983, and that meant looking at Darryl through the prism of looking forward to his debut, which was a preoccupation for three years as a Mets fan. Had I drawn 1987 or 1990, I would have approached Darryl differently. I liked hanging out with his potential in ’83. I loved knowing we were on the verge of something special with him and his team. I loved that we couldn’t be sure of it then because you can never be sure. I loved not defaulting to something I’ve really come to disdain, the bit where a Mets fan can’t look at the 1986 Mets without grumbling that they should’ve won more. We won in 1986. I would’ve liked more. Who wouldn’t? But that’s postscript. The story was and is Darryl Strawberry was frigging amazing.

What I wrote about Ron Hunt, on August 7, was a year in the making, you might say, though he wasn’t even my original draft choice for 1963 (apologies, Tim Harkness). On August 9, 2019, I had the good fortune to spend a little time in the presence of Ron and his family as he greeted fans at Citi Field. I hadn’t written one word about it here because that was the night Todd Frazier hit his three-run homer off Sean Doolittle, Michael Conforto whacked a walkoff hit, Pete Alonso grabbed Conforto’s shirt, and a rapidly developing playoff chase took precedence. I kept meaning to write about the rest of that night, which was amazing to live through on so many levels, but never got around to it. The Hunt portion, still in my notebook, dovetailed with this assignment, the only one that involved a Met I never saw play as a Met. Instead of it being an academic exercise, I got to take it personally, and I’m delighted I had that opportunity.

I already did meta for Joe Orsulak, AMFAS subject for 1993. As I wrote on August 11, I wasn’t completely certain why I wanted to profile Joe, other than I’d always said he was one of my favorite Mets…except I still wasn’t sure why he so rose in my esteem. And I’m still not, but I do like him and I did like thinking about him again.

Ike Davis, on August 21, was a vestige of another age. When I selected him in the AMFAS draft of 2011, I congratulated myself on the coup. I had our future superstar! I’d have so much to write about! That was based on Ike’s rookie season of 2010 and all the expectations it raised. Fast-forward nine years. Ike Davis’s Met career was long over and faded into the background. I’d written probably twice a year about his ultimate shortcomings while Ike was not living up to expectations about his arc. I didn’t want to write about the same damn thing. I remembered that my late friend Dana Brand, who lived only long enough to see Ike fall down in Denver and essentially never get up, was once kind enough to praise my “unusual techniques and genres to present the experience of the Mets: lists, dialogues, fantasies, glossaries, etc.” Well, I reasoned, if it was good enough for Dana, it was good enough for Davis, thus instead of another expository essay, I imagined some wise guy at the track giving me a can’t-miss tip on this kid running in the ’10th. Paired with my epigram of choice that day — the Guys & Dolls number about having “the horse right here” (a favorite of my mother’s) — it allowed me to fashion an old tale in a new light. Thank you, Dana.

When I got to Jose Reyes on August 25, I had a plan. Each of my next four Tuesdays starting with that one would encompass sort of a mini-countdown: second-favorite position player; second-favorite pitcher; favorite position player; favorite pitcher. Events would disrupt my planning, just as events disrupted Jose’s road to unimpeachable Met immortality. I chose 2007 for Jose because it demonstrated the absolute apogee of his abilities and indicated the beginning of realizing he was far from perfect. Still close enough to the innocent Jose of whom I’d grown so fond that I felt comfortable being mostly effusive about Reyes before having to get real. I still love the guy. That might be dangerous.

Tom Seaver was not slated for September 4, but how was I gonna write about any other Met two days after we learned of Tom’s death? Gil Hodges would regularly bump other pitchers to accommodate Seaver, so I guess it was appropriate that Tug McGraw had to wait another few days. I had decided to write about Tom in 1971, but how exactly? By transporting myself back to 1971. There was no point in telling the whole Seaver story that day because for two days we’d all been doing that. Instead, I got very specific. Tom the idol whose number I had to wear in Pee Wee League. Tom the “author” whose book I had to read as soon as my mother bought it for me. Tom the pitcher whose win total had to reach 20 games by the end of the year. That was the Tom Seaver I lived with in 1971. That was the Tom Seaver I called my favorite player then. I realized that was the Tom Seaver I call my favorite player still.

Tug McGraw came in from the bullpen on September 8. Just as his essay was postponed, “his” year was pushed back, at least from where it should have been. He’d have been better slotted in 1973, except we had Willie Mays there. Willie could have fit well in 1972, except we had Gary Gentry there. Gary would have been ideal for 1969, except we had Donn Clendenon there. Donn might have been just as at home in 1970, except we had Tommie Agee there. Tommie came over in 1968, but we had Cleon Jones there. And nobody was touching Tom Seaver in 1971. Musical chairs were a fact of AMFAS life for the Mets who contributed to our most memorable miracles (apologies to the seatless Met greats of the era). Anyway, I was doing the year Tug was traded, 1974, maybe the last Met season for which my detailed memories are fuzzier than they are clear. I do remember the Mets being a big letdown in general, nobody more so than McGraw, which is why when it came to writing about ’74, I pegged Tug to his trade as much as the career that preceded it. That I remember very well and that was the unusual trade in Met history where both teams involved made out pretty well. It also gave me an excuse to say a few words about John Stearns, the one Met I was genuinely sorry I didn’t find a season for in all this.

Mike Vail was September 1975 for me, so profiling him in September 2020 was a must. I noticed that when I wrote about Vail on September 18, I could feel my AMFAS voice changing, just as I suppose it was doing when I was 12 going on 13. My understanding of the Mets was deepening as I moved into adolescence. I was a little less childlike, just slightly more adult. I don’t know that I’ve progressed all that much even at this late date.

“FONZIE WAS SO GREAT!” and “FONZIE’S TEAMS WERE SO GREAT!” probably would have covered all I had to say on September 22, but I attempted to be a little more articulate than that regarding Edgardo Alfonzo and 1997. Not much more articulate, though. That’s a symptom of how viscerally I cherish Fonzie and that first year when his Mets broke through. Do the Fonzie, indeed.

Pete Alonso on October 2 endured a bit of the Ike Davis syndrome, as doctors call it. When I grabbed Pete in the AMFAS supplemental draft Jason and I conducted in March, I was excited that I was gonna get to write about the most dynamic contemporary Met in captivity. Months later, the Polar Bear had melted a little in the heat. I waited until the 2020 season was over to assess where he stood after two years in the majors. It was more fun doing the part where I revisited the feats of his unprecedented rookie year. This is what you run into trying to take the long view of a career still in progress.

Dwight Gooden was first going to appear in July, adjacent to my mother’s birthday because she liked him so much. But he kept getting pushed back. He was going to appear for sure on September 8 because of that countdown-within-a-countdown plan I described above, but Seaver’s passing changed all that. Getting to Doc on October 6 was fine. He’d completed his singular 1985 in early October. His 1985 was so singular as a whole that, while it’s often cited as the best individual Met season ever, its elements are never really dissected, which is what I set out to do. It’s also impossible to write about Doc without “…and then, he tested positive,” but I swear I don’t see that as the defining episode of Doc’s Met career. I’m Team Half-Full.

Matt Harvey was such a tabloid drama that I thought that was the best way to approach him and his 2016 on October 16. Bringing “Scott Boras” and “Sandy Alderson” into the story — and going as meta as I could get away with — turned a potential frown upside down.

Lee Mazzilli, profiled on October 20, was an outsize figure for someone who was a fairly average ballplayer. Such was the context of rooting for the Mets when Mazzilli was at his best. I’m particularly gratified that Lee had a 1986 coda to his 1980 story. I didn’t write much in this series about the Mets when they were in their larger-than-life phase — Jason covered 1986 through 1992 — but getting to ride along with My Guys of that period in earlier, slighter times (Mookie and Mazz in particular) and feeling them experience the ultimate World Series payoff was vicariously gratifying. I wish the Mets won a lot more than they did as I was fitfully coming of age as what we’ll call an adult, but I gotta tell ya, I wouldn’t trade the journey from the late ’70s to 1986 for anything.

Steve Cohen interrupted what I was deep in the midst of writing on October 30. He also changed my long-term plan for the AMFAS finale. But on the Friday that he was approved by MLB’s owners to buy the Mets, there was no other story I could see me dropping in our readers’ laps. Thus, Steve Cohen became A Met for All Seasons, 2021 edition. My original notion was to give that honor to To Be Determined. It was gonna be a whole thing. I’ll gladly swap the conceptual for the reality.

John Olerud, bumped to November 3 by Cohen, was given room to run. As if Oly (cycle notwithstanding) could run. Then again, we did run to glory with John batting third almost every day in 1999. This was my last chance to really dwell in what may be my favorite era of Mets baseball — though sometimes I think whichever one I’m writing about is my favorite — and I wanted to make it count. Who better to drive us in than Olerud? (Side note: this published on Election Day, and I was determined to get Oly’s essay up before other, more pressing issues distracted even the hardest-core among us from Mets of the past.)

Ed Kranepool had to end the series. Never mind To Be Determined, my initially penciled-in entrant for November 13. Ed was and is the personification of A Met for All Seasons. Though any notion that I had a maximum word count for any given column disappeared back in spring, I really let my Krane flag fly as I traveled to his and the series’s final year of 1979. Midway through I decided I wanted to explicitly mention each year Ed played. When I got to the end, I realized I forgot to specify 1963, so I went back and put it in. I had so much fun doing this one. I had fun doing all of them, really. And I had fun sharing them with you.

Thirty-first paragraph alert: Thank you for your indulgence today, thank you reading year-round. See you in 2021.

|

|

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts (we got a new one this year), and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or got stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts (we got a new one this year), and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or got stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.