The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 22 May 2015 8:32 am What are the Mets historically on the field of play if not outstanding pitching, reliable defense and frustrating offense whose capability for power and speed emerges mostly in sporadic fashion? This is their personality profile through the years. Some seasons the composition varies, but this is what one has been conditioned to expect if things are going reasonably well.

On Thursday afternoon, the Mets were relatively true to who the Mets tend to be and things wound up going more than reasonably well. There were three components of their game against the Cardinals that stood out.

1) Jacob deGrom threw a Metsian start in the best sense of the phrase: Eight innings (that might have been — gasp! — nine except for concerns over body part soreness) in which he gave up one hit and no walks while striking out eleven. Allowing no earned runs, striking out double-digit opponents and walking nobody is a rarity in franchise annals. Tom Seaver had a start like that once; we know it as the Imperfect Game of July 9, 1969. Matt Harvey, two years ago as he unspooled the White Sox, had a start like that once. R.A. Dickey in that mythic 2012 one-hitter at St. Petersburg that the Mets clumsily attempted to litigate into a no-hitter also had that kind of start once. Now deGrom has one.

And those guys are it. Four pitchers, four starts matching the statistical criteria at hand. But a lot of starts in the Mets backstory were proximate enough to what deGrom did. This is who the Mets were the first time they were a pretty good to very good team. They pitched so well you couldn’t believe they didn’t win. Sometimes you had to believe it because they hit so poorly, they couldn’t score. it’s an identity they keep coming back to as if by reflex.

2) The Mets hit into four double plays in the first six innings, while Juan Lagares ended one of those other two innings by getting picked off first and thrown out at second. As Jacob was getting stronger, potential rallies on his behalf were getting snuffed out left and right, leading to the possibility he was in for a matinee version of what afflicted his staffmate Monday night. Harvey pitched great for eight innings; the Mets scored one run; Jeurys Familia gave it back in the ninth.

By the time the Mets fell victim to their fourth twin-killing, they had provided deGrom with two entire runs, so maybe the worst wouldn’t happen. Or maybe some Cardinal named Mark or Matt would detonate whatever portions of Citi Field they inadvertently left standing Tuesday and Wednesday when 19 Redbirds flew across the plate.

3) Lucas Duda blasted two home runs. I mean blasted. Maybe not Mark Reynolds “go see if the Iron Triangle has a dent in it” blasted, but authoritative and effective enough to count for four RBIs in bold type. John Mayberry’s second RBI grounder of the week notwithstanding, Lucas accounted for and embodied the bulk of the Met offense on Thursday. You’re not shocked to learn Lucas Duda hit a home run. You’re surprised but not stunned to learn Lucas Duda hit two home runs in the same game. Just on Mets fan instinct and roster DNA, you’re shocked that a Met is capable of hitting two home runs in any one game.

The New York Mets have traditionally been where imported lumber turns limp on arrival and where growing our own has yielded mostly a buzzkill. The powerful exceptions to the rule have been thrilling because they so rarely break the mold. Duda is a mold of his own. We saw it in the second half of last year. We got a big, hearty glimpse of it again Thursday. It was indeed thrilling. Duda’s two homers complemented rather than stole the thunder from deGrom’s eight brilliant innings. They obscured the DPs, the CS, the general lack of speed and the defense that’s nothing special outside of center field.

When the Mets reach an occasional apex, they have the kind of Harvey/deGrom pitching we automatically identify with them because we were exposed to Seaver or Gooden or have been taught to assume they represented the norm. When the Mets are so good that you never worry that they’re going to go bad, they have more Lagareses than Floreses in the field. When the Mets’ goal is winning rather than finishing, it usually means that somewhere along the way they got lucky and found a Mookie or a Jose to run the hell out of the bases. If the Mets have it all going on, it’s likely somebody like Strawberry or Piazza has emerged to regularly threaten the other team’s pitchers. And when the lower-case wild cards fall into place — the unhittable middle reliever, the lefty pinch-hitter who inevitably comes through, the scrap-heap veteran who suddenly fills a gaping void in the lineup — that’s when the Mets redefine “the Mets” completely for the better.

Those aren’t the Mets we are programmed from experience or legend to see on a recurring basis, but when we do see them, they are a sight to behold.

We don’t really have those Mets at the moment. But Thursday, when we won 5-0, we had enough of the elements that make those kind of Mets. We had deGrom. We had Duda. We made due. We did all right.

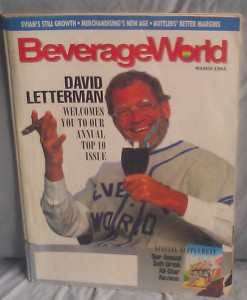

by Greg Prince on 21 May 2015 12:13 pm  Nice jersey, Dave. David Letterman built an impressive ratings lead once he moved from 12:35 AM on NBC and took over the 11:35 PM time slot on CBS in late August of 1993. All felt right with the comedic if not baseball world as that particular summer turned to fall. The guy who deserved to host The Tonight Show was kicking the ass of the pretender who wound up with the job. What Dave was doing on The Late Show was better, and I don’t just mean comedically. He took himself, his crew, his sensibility, his “brand” and built something from scratch that made Tonight irrelevant both critically and competitively.

Half of that equation didn’t last. The Jay Leno version of The Tonight Show never much improved, but the ratings flipped and eventually Letterman fell behind in the Nielsen standings. Dave couldn’t keep up with Jay and he also trailed Ted Koppel on Nightline. When NBC erected a billboard in Times Square to brag that their man was “#1 In Late Night!” CBS (at Dave’s urging) responded that theirs was “#3 In Late Night!”

Even Dave’s billboard was funnier.

The fleeting baseball point, if you haven’t inferred it coming down Broadway, is that the 2015 Mets are no longer #1 in the N.L. East. They topped the division for more than a month, but it didn’t last. Maybe it couldn’t last. The Washington Nationals have a powerhouse lineup, almost as strong as the one NBC fielded in prime time by the mid-1990s. Their ratings were bound to surge.

The Mets? They’re still the Mets. They’re still first in our hearts, despite nights like Wednesday, when it was obvious they were so looking forward to watching Letterman’s finale that they were distracted from the business at hand, a game they lost to St. Louis by the official score of a forfeit. When Bartolo Colon a) can’t parlay a ten-foot E-2 and advancement to second and third into a run because he doesn’t know from tagging up and b) finally walks a batter, you know it’s not their night.

By August 30, 1993, when Dave debuted on CBS, few nights of the season joined already in progress had belonged to the Mets. A victory over the Astros that Monday evening at Shea lifted their record to 46-85. They pulled to within 35 games of first place with the win.

Yes, that kind of year, one that had drawn decreasing amounts of attention, until a familiar voice spoke up. David Letterman, who’d been off the air for the two months when the Mets were definitively crashing through the floor of ineptitude and plunging into obscurity, had an instant, easy New York-based target for his nightly monologues and so forth. The 1993 Mets would no longer be allowed to fade into the offseason in private. In the last weeks of their conscious life, they were repositioned as a national joke.

Thus, Top 10 New York Mets Excuses, as broadcast by the host who was still very much #1 IN LATE NIGHT! on September 23, 1993.

10. All those empty seats are distracting

9. Part of a grand plan to make Florida Marlins overconfident next year

8. Pitchers on other teams throw the ball really fast!

7. Two words: Guaranteed contracts

6. Mistake to let Don Knotts bat cleanup

5. Play so much golf during season thought lowest score wins

4. Baseballs harder to throw than explosives

3. Drank Slurpee too fast; got a “brain-freeze”

2. Didn’t scratch themselves enough

1. No one named “Mookie”

In spirit if not fact, you couldn’t say any of this wasn’t accurate. The Mets’ record was 52-100 by then — were you really going to feel compelled to argue that Joe Orsulak and not Don Knotts was their previous game’s cleanup hitter?

I was a little miffed that Dave kept batting at the Mets piñata in the years to come, considering that no Mets team in what remained of his brilliant tenure was ever as awful as the one from 1993. Besides, I still remembered Dave winning a bet with the testy mayor of Houston in October of 1986 (an enormous photo of Mookie Wilson was supposed to be displayed at their city hall). I still remembered being giddily exhausted from having witnessed a tickertape parade on 10/28/86, listening to Bill Wendell introduce that night’s show as coming from “New York, home of the World Champion New York Mets,” and thinking that was the first time I’d heard a “straight” identification of Late Night’s hometown in the opening credits. I still remembered Dave, for no particular reason, setting up a projection screen in the Shea Stadium parking lot and beaming his show live to Flushing at 5:30 one summer afternoon when the Mets were out of town.

C’mon Dave, I thought as he took whack after whack at the perennially unsuccessful Mets, go easy on us. It wasn’t that long ago we were sort of there for each other.

But I couldn’t stay mad. He was Dave. He was the best. Besides, he had me on his show.

Albeit as a prop.

This was also in 1993, the first half of the year, when he was still the host of Late Night, though it was known that would be ending soon. This unfolded amidst the storm of coverage regarding the possibility Dave might replace Jay. Jay had succeeded Johnny Carson the previous May and it had been a debacle. Dave’s contract was running out. NBC wanted to keep him in literally the worst way — first by convincing him he should stay at 12:35, then by having him cover up their initial mistake for them.

Because the Late Night mind was always working, even under extraordinary stress, somebody there had an idea. Dave wasn’t doing traditional press…but what if he made his own kind of media tour?

With the conceit that he just wasn’t getting enough publicity, Dave’s people arranged for him to be on the cover of five aficionado/trade magazines you never would have heard of unless you had a very good reason to. One of them was the one I worked for.

We were contacted. Dave’s producer asked our editor-in-chief if he’d be interested in appearing. To our editor-in-chief’s everlasting credit, he asked if we could bring two editors: him and me. The producer said yes. We were also asked to bring a photographer or at least a camera to shoot him for our cover.

The bit was postponed once, what with Dave’s contractual limbo obscuring everything else at that moment, but we were rebooked once the dust settled. We were given a new date. I groaned when I realized I was scheduled to report for jury duty that day. I wrote a pleading letter to the judicial jurisdiction in question and asked for my own postponement in light of this singular opportunity. Bureaucracy had a heart and let me come later in the month.

Having been legally cleared to attend, I engaged the services of a legitimate fashion photographer, the husband of my wife’s co-worker. We were going to shoot David Letterman for the cover of Beverage World and were taking no chances on quality. Then we gathered four items: a curly straw (the photographer’s idea); a clear glass (from a set Stephanie and I had been given when we were married a little more than a year before); a can of a leading national brand of cola (we couldn’t show favoritism, which is why we needed the glass) and a custom-made BEVERAGE WORLD softball jersey. It had nothing to do with our company softball team. One of our advertisers made promotional items and the salesman whose account it was asked, in essence, “pretty please…?”

Come the big day, we gathered up our gear, ourselves and an offering for Dave (an assortment of oddball beverages they should feel free to use in Supermarket Finds, including a Lawrence Taylor sports drink which featured LT’s face on the label, which I was always disappointed didn’t come in a 56-pack) and alighted to 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Security signed us in and directed us to a dimly lit room that reminded me of the basement we had in our house when I was growing up. The segment producer met us there, allowed us to set up and, all of a sudden, we had our brush with greatness.

Dave walked in.

Dave. David Letterman. David Letterman whom I’d been watching since 1982. David Letterman who warmed my heart every time he made non sequitur reference to a “lovely beverage”. It was a natural that he and his staff chose us as one of the five magazines whose cover he’d grace. (The others, in case you’re interested, were Heavy Duty Trucking, Convenience Store News, Dog World and Cats.)

A few things I noticed right away: Dave was incredibly tall; Dave was incredibly tan in winter, having just returned from a post-CBS announcement vacation in sunny Bermuda; Dave hadn’t shaved; Dave was cordial; Dave introduced himself by name because how would have we known who he was otherwise?

From there, Dave put himself in our hands. We gave him the softball jersey. He threw it on over his shirt and tie and buttoned it up. We asked him to hold the glass with the unidentified cola and sip it through the curly straw. He immediately identified which leading brand it was. Whatever our photographer asked for in the way of posing, he went with. Our photographer shot Dave. Dave’s crew shot our photographer shooting Dave.

When the photo session was over, it was Late Night’s turn to use my colleague and me as props. We stood on either side of Dave and Dave riffed on beverages for several minutes. He wanted to know if 7UP was planning on “going brown” (which only true BevHeads by then recalled had happened in 1988 with 7UP Gold). He looked at me and told me it appeared I enjoyed a few beverages. I laughed. I knew enough not to attempt to match wits. Dave had enough wits for the three of us.

The segment producer decided they had enough and that was that. Dave shook each of our hands again, and was off, probably to prepare to knock out the next wacky magazine interaction. This was Monday, when they taped their bits. Everybody was on a schedule. We thanked Dave profusely. We thanked his crew profusely. We packed up our stuff. We left behind our Lawrence Taylor sports drink.

Not quite three months later, we were alerted we should watch the episode of April 30. It was our episode. We were part of a montage. Our names were on the screen. Dave was shown saying something funny to us. My colleague and I laughed. Dave’s BEVERAGE WORLD softball jersey was on television for the regular world to see. All the photo shoots were excerpted. At the end, each of the magazine covers came spiraling onto the screen. Ours was saved for last and landed in the middle, perhaps a testament to the value of hiring a fashion photographer, deploying an expert art director and putting some thought into context.

The other magazines were like, “Uh, here’s David Letterman on our cover for some reason.” We had serendipity on our side and decided to run with it. See, Dave was on the cover of our March issue, and the March issue of Beverage World was annually our Top Ten issue, the one where we published our rankings of the best-selling beverages in the U.S.A. I had written a Top 10 Reasons David Letterman is on the cover of this month’s Beverage World list to accompany the statistical feature. I’d share some of it with you, but little of it is funny 22 years later unless you were in the beverage business 22 years ago.

On the night of April 30, 1993, when I was a mostly silent and utterly cheerful component of David Letterman’s trademark “found comedy,” the New York Mets were 8-13. We didn’t yet know just how comical they were going to be by the time our host arrived at CBS. Dave, meanwhile, just kept getting better at what he did until he finally decided to stop in 2015, the night the Mets could no longer brag they were #1.

by Jason Fry on 20 May 2015 1:17 am Jon Niese has a suspect shoulder that demands periodic trips to the 15-day DL, and a mental approach to his craft that calls for the 80-year DL. He begins a game with a plan, and was born with the talent to execute it. But he’s incapable of adjusting if anything goes wrong, whether it’s his location or which pitches are working or his defense or the umpiring or bad luck or his horoscope or the U.S. dollar/Burundian franc exchange rate or whatever else doesn’t go exactly the way he thought it would go while he was in the consequence-free cradle of the bullpen.

Everybody has a plan until they get punched, to quote Mike Tyson (no, Baseball Reference, not that one) and Niese has a glass jaw.

But that’s not the real problem with Jon Niese.

(Nor is it that I detest him, though that’s also true.)

The real problem is that Niese is no longer better than the Mets’ other options for the starting rotation. Noah Syndergaard is ready for the big leagues — which doesn’t mean that he’ll dominate, just that he has nothing left to learn in Las Vegas. And Steven Matz is very close to that same status.

Last year this didn’t matter, because Syndergaard and Matz were part of the future. Now they’re part of the present, and the only way to discover what they’ll become is by watching them challenge big-league hitters and be challenged by them.

Niese’s days of becoming something, on the other hand, are over. He arrived in the big leagues seven years ago, and is one of four Mets with tenures that reach back to Shea Stadium. (Your others: David Wright, Daniel Murphy and Bobby Parnell.) We know Niese’s strengths, and oh boy do we know his weaknesses. He is what he is — a No. 4 starter who might have been more if not for injuries and his own limitations. That’s not news. What is news is that now he’s in a rotation with a bunch of potential No. 1s and No. 2s, and very soon there won’t be enough spots for everybody.

So trade Niese, right? Great idea, but who’d take him? Other teams see the injury history, the suspect mechanics and the dreadful body language on the mound. They hear the muttered postgame alibis and Terry Collins‘ barely suppressed frustration. (His comments tonight about Niese not using all his pitches were telling — as was Collins’ bafflement about what happened in Chicago.)

At the end of 2012 the prospect of having Niese under contract through 2016 (with two more years of club options) seemed like a bargain, but the Mets needed him then. Now that he’s in the way and the Mets don’t need him, the prospect of two more years of Niese is a gamble. The Mets are left hoping for a sucker at the table. Good luck with that.

* * *

Since we must, let’s talk about the game inflicted on us tonight. I seized a chance to catch up with an old friend and so saw the first two-thirds in snatches on a bar TV. Wait, Lagares didn’t catch that? Why is no one covering first? How many runs is that in this inning? What are the Nats doing? They’re playing them, really? Who the hell do I root for, plague?

When I got home I asked Emily if Niese had been unlucky or terrible. Her reply was that he’d been a little unlucky and then a lot terrible, which is too often the only Jon Niese scouting report you need. Beyond that, well, Murph had a quintessential Murph game, hitting a home run into the outermost precincts of Utleyville that delighted him and us, and then unaccountably abandoning his post on a bunt play that second basemen need to execute in their sleep. (Actually, narcolepsy would be a plausible explanation for some of Murph’s Murphiest moments.)

Oh, and Darrell Ceciliani — Met No. 996 if you’re scoring at home, which I hope the Mets are — got his first big-league hit. Soon after that, he got his first experience of ending a game by striking out. That kind of night. Really, the best thing about this one was that it ended.

by Greg Prince on 19 May 2015 9:24 am I’d like to teach the Mets to score with regularity. I’d like for them to cross the plate and do it constantly.

Or at least while Matt Harvey is on the mound.

Monday night the Mets did eventually find a second run to keep the one they’d rustled up ten innings earlier company. By then, they and the Cardinals had played fourteen innings — five more than is generally required, six after Dr. Harvey left his moundtop lab, where he was expertly dissecting St. Louis batters to further advance the cause of humanity.

Harvey (8 IP, 6 H, 1 BB, 9 SO, 0 R) logged another start that was as dominant as it had to be without quite being all-encompassing awesome. He doesn’t seem as Dark Knight confounding as he did before they (oh, by the way) operated on his elbow, yet look at what he does. There are small clumps of baserunners, but they don’t much go anywhere. It gets later, he gets better. Someone flashes a stat that he’s not so dazzling when he surpasses 100 pitches. He surpassed 100 pitches against the Cardinals. His 105th pitch retired Matt Holliday and produced an eighth zero for the top line on the scoreboard. Matt gave himself a quick clap into his glove as he exited.

I hope he didn’t pump his fist through a wall when the top of the ninth came around and Jeurys Familia couldn’t do for him what he’d been doing for Met starters all season. The Cardinals scratched out the one run that kept Harvey from notching a sixth win and kept those of us who can’t turn away from Mets baseball tuned in for a couple more hours.

Eventually we arrived at an unambiguous ending. Without much offensive exertion (walk, walk, grounder, intentional walk), the Mets loaded the bases in the bottom of the fourteenth, when it was still 1-1. John Mayberry, Jr., pinch-hit and rolled a ball to a spot that kept Eric Campbell from being thrown out at home, which is to say he drove in the winning run, but that somehow doesn’t sound like something John Mayberry, Jr., would do. But he did, and the Mets won in fourteen, 2-1.

Carlos Torres got the win. He pitched two flawless innings. Alex Torres and Hansel Robles were similarly effective. They were about as good as Matt Harvey. I suppose we could say all of them were matched by John Lackey and the five Redbird relievers who preceded the fourteenth. We have to give those guys credit, right? I mean they allowed the Mets one run through thirteen. That’s some kind of pitching, too.

But if we do that, we can’t moan about how the Mets barely hit and make our gripes stick — and we love doing that. The Cardinals have scary bats by both reputation and performance; five of their starters are hitting .298 or better. The Mets’ pinch-hitters from last night currently sport averages of .083, .079 and .139. The guy who got the winning hit is Mr. .139. The .079 guy, Kirk Nieuwenhuis, is probably about to be the guy who shuffles off this Metsian coil to make room for Darrell Ceciliani. Who’s Darrell Ceciliani? He’s the guy from Las Vegas who has a low bar to clear in terms of Met bench contributions.

There are a few flickers of light emerging among the Met regulars, but Monday night was a four-hour, fourteen-minute brownout, another caper in which they expertly camouflaged their offensive capabilities. In the end, the Mets saw their way clear to two runs, which was enough to achieve the objective of the evening — winning. It would’ve been much nicer had the win been affixed to Harvey’s record. We know pitcher wins are antiquated nonsense, but they still get kept track of. Harvey has thrown sixteen consecutive scoreless innings, fifteen of them in his last two starts. The Mets are 1-1 in those starts. Harvey is 0-0. His season ERA has dipped in that time from 2.72 to 1.98.

Something doesn’t quite add up there. But what else in the world of Met aces is new?

by Greg Prince on 17 May 2015 8:21 pm They didn’t much hype The First Home Start In The New York Mets Career Of Noah Syndergaard, did they? Just as well. When they hype that sort of thing, it seems to implode. They hyped Matt Harvey’s Citi Field debut in 2012 and it was one of the worst outings he’s ever thrown. They hyped Zack Wheeler’s Citi Field debut in 2013 and that Sunday afternoon ended with Anthony Recker pitching.

On the other hand, over these past four seasons, the Mets called up Collin McHugh, Jacob deGrom, Rafael Montero and Noah Syndergaard and when they were needed to pitch in Flushing, they were more or less told, “Have at it.” There was no special t-shirt deal, no cringey slogan, no sound of Lou Gramm narrating that this here feels like the first time.

Syndergaard (like Harvey and Wheeler) had gotten the hard part out of the way on the road, but still, pitching in front of your prospective fans is a distinction unto itself. I’d add “…in New York,” but I don’t really believe that. If you’re pitching in Times Square, c. 1975, that would be an urban challenge. Pitching in the aspirationally adorable fauxback ballpark where as many people seem to come to chow down as they do to root on doesn’t strike me as inflicting an extra layer of stress. The “New York fans” concept, at least as it applies to Citi Field, is a self-flattering myth. Don’t be fooled by the oddball rabid caller to sports talk radio. Having now attended 187 post-Shea home games since 2009, I will testify that relatively few who pay their way in are out for blood. At our worst, we’re morosely disengaged. At our best, we’re surprisingly cheerful.

Must be the food that settles our nerves.

Today we welcomed Syndergaard warmly. Those who understood that this was our first official up-close look were enthusiastic. Those who didn’t know what was going on could amuse themselves in gourmet hamburger lines. It left more room for the rest of us to feast our eyes on the Noah kid in town.

Impressions from the eighth row of Section 519: Syndergaard — I’m going to resist this Thor thing for now — looks as much like a starting pitcher as any I’ve seen in recent years, and, as noted above, we’ve seen quite a few begin to make a mark for themselves. He looks like the kind of pitcher I’d hate for the Mets to face. He looks like he knows what he’s doing out there, which surprises me a little, what with the intermittent bulletins about his “maturity” issues (a.k.a. he tweeted too much). I don’t know how stern his stuff is for 22, but there was no questioning his jib’s cut in his second major league start.

The Brewers are presently at the bottom of the N.L. Central barrel, but a lineup with Ryan Braun, Aramis Ramirez and Carlos Gomez is test enough, and Syndergaard acquitted himself beautifully for six innings. The sixth, of course, was the inning to beware. Not only might have his gas gauge begun to point to dangerously low, but he had to recover from the sight of Gomez on the ground, a victim of one of the rookie’s fastballs that ran far too up and a little too in.

If a New York ballpark was the cauldron of hostility lazy narratives make it out to be, then I doubt the crowd would have applauded three different times in support of Carlos’s well-being: once when we saw bodily movement, once he sat up, once when he walked off the field. Gomez’s Met pedigree isn’t so deep that we wouldn’t have been decent about his condition without it. Fortunately, Carlos reported being all right, and when we got back to the game, a contrite Noah resumed his assignment.

Milwaukee had two on with nobody out after the scary HBP. Syndergaard struck out the next batter, Khris Davis. Braun nicked him for a RBI single to right, but he took care of the capable Adam Lind and then Ramirez, allowing Noah to exit to knowing applause. He was up, 5-1, and on a glide path toward his first major league and Citi Field win.

The reflexive fears that the Mets wouldn’t “save some of that” for Sunday after the delightful 14-run outburst of Saturday night proved unfounded. They tallied nine fewer times, but more than enough was provided for one of the most promising young pitchers in baseball to defeat the one of the worst teams in the sport. Nobody in our lineup is hitting .300 and few are topping .250, but at least for the time being, the Mets have returned to the mode where they’re getting done what must be done. My buddy Joe and I agreed that this was a game that cried out to be broken decisively open, but once Syndergaard was through six, we and our 32,000 friends could relax and enjoy…despite the disturbing omission of Bobby Darin’s “Sunday In New York,” a Shea/Citi Sunday staple for the previous 14 seasons, from the PA menu. Small thing, but I loved hearing it, especially on those baseball Sundays when it was warm like it was today and the Mets were winning like they were today.

Missing musical cue notwithstanding, no complaints on this Sunday in New York, when Noah Syndergaard made a debut that was more auspicious than conspicuous. It wasn’t a laugher, but it was definitely a smiler.

Life’s a ball, let it fall in your lap.

by Jason Fry on 17 May 2015 1:05 am A laugher after a long stretch of laughees? Turns out it makes for some complicated emotions.

After the Mets scored a lone run early, I sourly thought, “Well Jacob deGrom, there’s your offense.” I also thought that our long-legged, long-haired rookie of the year in recovery looked a lot better than he had in recent outings. It was a thought that I backed away from like I’d put my hand on a blazing stove. I’d thought Noah Syndergaard looked pretty great in Chicago. I’d counseled myself to think well of Jonathon Niese for looking good against the Cubs.

Both thoughts had been precursors to disasters of various sorts. I stopped thinking good things and watched warily, certain that bad things would happen and the night would end with a discussion of the first-place Nationals.

And then the Mets decided to drive in runs for half an hour.

They sent 16 men to the plate, which is batting around and then some no matter what side of the 9/10 divide you stand on. The ninth-place hitter — Wilmer Flores — drove a grand slam into the Party City deck. The pitcher got two hits in the inning. There were deep drives but also balls served over the infield. It was like some baseball madman took all the luck that had been missing during our Chicago horror show and crammed it into one half-inning.

I’ve seen three of the Mets’ four innings in which they scored 10 runs or more. (I don’t remember the 1979 uprising against the Reds, though my blog partner might.) The 10-run demolition of the Braves in 2000 is tied with the Grand Slam Single for the greatest baseball moment of my fandom, the perfect sublimation of weeks of agony into a few seconds of pure joy. The 11-run, double-grand-slam ambush of the Cubs in ’06, on the other hand, was baseball goofiness, like finding the cheat code on a videogame.

This 10-run inning? It was … odd. There was happiness, of course — scoring 10 in an inning is always going to be satisfying. But there was annoyance, too — where the hell had this been for the last week, when the Mets weren’t just losing but sleepwalking through awful, unwatchable games? There was the familiar baseball fear that one was seeing a homestand’s worth of runs thrown around like singles at a strip bar, which is arrant nonsense but also impossible not to think. And, in an All-Star display of Mets fan paranoia, I was sure that the Mets would keep hitting and hitting while the rain intensified at Citi Field, leaving deGrom to struggle in the top of the fifth, the Brewers to try every stalling technique up to and including lost contact lenses, and the umps ordering the tarp brought out, after which it would stay deep into the night.

The game would be washed away. The 10-run inning that disappeared would become one of those secret handshakes shared by doleful Mets fans, and trotted out by columnists to demonstrate the depth of our despairing craziness.

The rain didn’t go away, but limited itself to trudging overhead the way we had in Chicago. DeGrom pitched just fine, and the Mets even put up another half-week’s worth of offense on the way to a win. Even a Madoff-era Mets fan can be too pessimistic.

by Jason Fry on 15 May 2015 9:26 pm 1. Bartolo Colon sucked.

2. Wilmer Flores made another error.

3. The bats did zero against a guy who came in with an ERA north of 7.

4. Dilson Herrera, one of the only players worth watching in this disaster, broke his fingertip and is headed for the DL.

5. Herrera will be replaced on the roster not by Matt Reynolds but by Eric Campbell. because when things are going great you don’t rock the boat.

6. I could go on, but fuck this bullshit. It’s still early; go salvage your Friday night.

7. Oh wait, it’s raining.

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2015 12:07 am Precedents don’t necessarily prove anything. All they tell us is whether something happened before, and it’s up to us if we want to take our clues from there.

Here’s the precedent that’s gonna kill us: If we fall out of first place — and, based on the results from Chicago and everything that’s been going on with Washington, it seems a matter of hours before we do — there’s no chance we’re getting back in.

That’s not a prediction. That’s the precedent. It’s not guaranteed; it’s just that there has never been a season in which the Mets (once the season is more than a couple of weeks old) have grabbed hold of a division lead, let go of it and gotten it back.

Think about it through the prism of our five division titles:

1969: The Mets famously took first place (“LOOK WHO’S NO. 1”) following Game 140, the first half of their September 10 doubleheader versus the Expos. They kept first place by sweeping Montreal and they never relinquished it.

1973: You Gotta Believe that when the Mets won their fourth in a row from the Pirates on September 21 — Game 154 — they moved into first place and didn’t for a second move out.

1986: After Game 10, April 22, the Mets were tied for first with the Cardinals. The Mets were off on April 23. The Cardinals weren’t. They played and they lost, ceding the top of the N.L. East to their archrivals in advance of New York’s eleventh game of the season. The only things anybody else saw from there on out were the Mets’ tail lights disappearing in the distance.

1988: The Mets passed the Pirates on May 3, Game 24. Nobody passed the Mets thereafter.

2006: It wasn’t wire-to-wire, but it was close enough. The Mets became a first-place club on April 6, Game 3. They stayed a first-place club clear through October 1, Game 162.

And in seasons when the Mets did take a lead on the East but stepped aside to let somebody else get ahead of them? Those seasons exist, plenty of them. But you don’t see them listed above with the Met division-winners, do you? It’s possible for such a scenario to unfold and not destroy any thought of finishing first. Teams dip out of first place and then climb back in for keeps with regularity. None of those teams, however, has been the Mets.

The 2015 Mets grabbed a piece of first place on April 15 — Game 9 — and gathered in all of it the next night. We are now past Game 35 and the Mets are still the sole occupants of the divisional penthouse. I doubt any of us were expecting to be there at all, so if we’re not ensconced for the long haul, you can’t say we didn’t see it coming.

What we can see coming is the Washington Nationals in our rearview mirror. They were eight back about eight minutes ago (technically on April 27, after both they and we had played 20 games). Pending Thursday night’s West Coast action or rainy lack thereof, the Mets’ lead is down to one game. The Nats have been playing as they were projected to. The Mets have, as the saying goes, come back to earth.

I think we can all agree, based on the last four games’ worth of said plunge, that earth is overrated.

If you watched the Mets lose every game they played this week at Wrigley Field, you’d probably also agree that this is all transitory bookkeeping. If the season were to end right now, the Mets would be in line to be division champs, but it would be one of those deals where the official scorer would use his discretion to award the win to somebody else. Besides, the way the Mets are playing, can you buy the Mets as a champion of even a short season? Or a short-season league? Could you see them prevailing in the New York-Penn right now?

The key phrase there is “right now”. As they say on Avenue Q, being absolutely terrible at most phases of the game is only for now…maybe. When your team isn’t hitting, it’s hard to imagine they ever will again. When your players’ heads aren’t fully engaged in the game, it’s hard to see them getting fundamentals religion. When just enough can go wrong on the mound, it’s hard to take solace in the notion that with pitching like the Mets have, they’ll never have a long losing streak.

They’re in the midst of a four-game losing streak as we speak. Thursday’s starter, Jon Niese, did nothing to halt it at three. This was the game in which the Mets hit for a while — three solo homers and a rare John Mayberry RBI sighting — but it wasn’t enough. We’re in one of those stretches where nothing is enough. The Mets, at the moment, have a surfeit of nothing.

Turning around this prevailing trend would help the first-place precedent immensely. If they don’t stop being a first-place club, well, duh, they won’t stop being a first-place club. If they do, they’ll have to shatter precedent to resume being a first-place club. The way things are going, if precedent is shattered, precedent will wind up on the DL for three months.

Now that I’ve got us all in a good mood, how about a precedent that indicates we’re not dead yet? Perhaps it will turn that Chicago frown upside down.

We were swept four games at Wrigley Field. That’s the good news? Not exactly, but it’s not the end of our hopes and dreams, assuming we’re not hoping for and dreaming of only first place. This very month fifteen years ago, you see, the Mets were on another road trip, this one to San Francisco. It was 2000, the first year of Phone Company Park, and the Mets had four games with the Giants on their schedule.

The Mets arrived by the Bay and nearly drowned. They lost all four. They looked horrible in doing so (hard not to). And then what happened? Long story short, the Mets won the Wild Card and happened to beat the Giants in the playoffs en route to making the World Series.

There ya go: proof that being on the wrong end of a four-game sweep doesn’t bury your season in this modern age. Actually, if you look at the trajectory of the last Met team to raise a pennant, you see some similarities to the current edition. After stumbling around a bit, the 2000 Mets surged as April ensued, putting nine consecutive wins together at one point. Next thing you knew, though, there was the beautiful new ballpark in San Francisco and an ugly beatdown at the hands of the home team. The Mets couldn’t have seemed less likely to be playing deep into October.

But they did. They were good enough to have won nine in a row. They were good enough to rebound from a bad trip. A decade-and-a-half later, they could use a Piazza, sure, but they do have a Harvey and they can’t possibly be as dismal as they looked at Wrigley. What’s more, unlike in 2000, two Wild Cards are available these days. The Mets already have a better record than every Wild Card contender in the National League.

And every team in the N.L. East! It’s easy to forget that after what we just saw.

We didn’t solve any of the issues plaguing the Mets but we did have a whole lot of fun talking about it on the Rising Apple Podcast. Listen in here.

by Jason Fry on 14 May 2015 12:34 am Last year the Mets looked kind of OK in the early going. On May 26 they lost a horrific 5-3 game to the Pirates, dropping their record to 22-28, but then won six of their next seven, including three of four in Philadelphia, lifting their record to 28-29. So they rolled into Chicago to take on the hapless Cubs, and all in all we were feeling pretty good about things. Win the series and they’d be at .500, and then we’d see.

They lost all three games at Wrigley. In the opener Zack Wheeler flirted with a no-hitter, which he didn’t get (if he had we’d all remember), but the Mets took a 1-0 lead to the eighth. Chris Coghlin hit a home run off Josh Edgin and the lead was gone. In the bottom of the ninth some lousy Mets defense and lousy Scott Rice pitching lost the game. The next day the roof caved in on Daisuke Matsuzaka, Dana Eveland and Jeurys Familia in the fifth and the Cubs won 5-4. In the finale the Mets erased a 4-0 deficit, after which Vic Black immediately gave up a home run to Anthony Rizzo. Two more runs scored off Jenrry Mejia in the ninth and the Mets were toast. They slumped off to San Francisco and lost all three games. From that point on, 2014 became a narrative about what would happen in some other year.

Which brings us to this year’s visit to Wrigley.

Matt Harvey didn’t have a no-hitter to flirt with, but he was pretty amazing anyway, carving up Cubs and leaving with a 1-0 lead. Carlos Torres came on in the eighth and gave up a game-tying single to Dexter Fowler, then got into trouble again in the ninth. The Mets summoned Familia, sent Johnny Monell in to catch for the first time in orange and blue (he did fine), and even tried various five-man infields, but Familia gave up a bases-loaded, one-out walk to Coghlan and we were beaten.

We’ve lost three in a row at Wrigley (and, IIRC, the last 452,315), we’re scoring less than three runs a game in May, and the Nationals are just 1.5 games behind us.

Blame the cruelty Terry Collins has inflicted on Torres’s arm. Blame the spaghetti-at-the-wall nature of relievers. Blame the inert bats. Blame the pretty decent ballclub currently occupying the DL. I don’t want to get into the blame game. I just want to not think about this game, or the Cubs, or Wrigley Field, or how this series feels exactly like the last time we arrived at Wrigley Field with pretensions of being something other than a first draft of something a long way from completion.

If you’ve had your fill of Wrigley like I have, too bad. They’ll be back at it at 2 p.m. tomorrow. So SNY told me while I was still reeling. The promo should have come with a trigger warning.

by Greg Prince on 13 May 2015 3:46 am “It was a start. I believe in starts. Once you have the start, the rest is inevitable.”

—Joey “The Lips” Fagan, The Commitments

Presumably somebody somewhere waited breathlessly for Bob Moorhead to make his major league debut, but it seems safe to say he didn’t carry quite the cachet to his impending initiation that Noah Syndergaard did going into Tuesday night. Besides, whatever Moorhead’s qualities as a pitcher, his big moment was bound to be obscured by a much bigger one.

Moorhead, you see, stepped up to the big leagues on April 11, 1962, and if that date looks familiar, you’ve been paying attention. That was the day 14 players made their Mets debut. That was the day the Mets made their debut. It was Game One for the franchise, Game One for all of us, really. But it couldn’t have been a bigger deal for anybody whose spikes were on the ground than it was for Bob.

Bob Moorhead was the only one of the extremely Original Mets — those who participated in Loss One (11-4 at St. Louis) — who had never played in a major league game before. Remember the historical rap on the 1962 Mets: they valued veteran familiarity over youthful promise, believing the best way to distract fans and buy time was to serve up recognizable names to our fair city’s disenfranchised National League diehards. That goes a long way toward explaining the presence of Hodges and Zimmer and Ashburn and so on. Still, expansion begets a widening of the job market. There was a net of 50 new positions to be filled in New York and Houston; the Mets were bound to break in somebody who’d never been a major leaguer before.

Their first somebody was Bob Moorhead, righthanded relief pitcher from Chambersburg, Penn., selected out of the Cincinnati system in the 1961 Rule 5 draft, which (in the spirit of Sean Gilmartin) heavily implies the Mets were compelled to keep him on their roster throughout 1962 if they wanted to keep him at all.

So they did. Moorhead made the Mets in Spring Training and was put to work as soon as possible. In that inaugural game, he became Casey Stengel’s first relief pitcher. Roger Craig, another of those veterans with a presumably marketable pedigree, had given up five runs in the Mets’ first three innings. Stengel pinch-hit for his starter in the top of the fourth and inserted the rookie reliever in the bottom of the frame.

The game was 5-3 when Bob entered in the fourth, 10-4 when he left after the sixth. No, it wasn’t a storybook big league debut for Moorhead, but his foot was in the door. The late Bob Moorhead didn’t help the Mets win on April 11, 1962 — or win very often in general — but he served a valuable purpose in the greater scheme of things. He nudged that door open for other neophytes to get their shot as Mets.

After Moorhead came Ray Daviault, Jim Hickman and Rod Kanehl in the April days ahead, Rick Herrscher that August and, representing the first marker toward the Met long haul, Ed Kranepool in September. Ron Hunt and Cleon Jones headlined another class of new big leaguers in 1963. Within a couple of years, Mets fans would begin to anticipate and welcome youngsters who’d make their impressions stick: Ron Swoboda, Tug McGraw and Bud Harrelson in 1965; Nolan Ryan in 1966; Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Ken Boswell in 1967…and before you knew it, it was 1969.

In between were a lot of Mets who made it in the sense that they reached the big leagues for the first time as Mets, which is surely an accomplishment unto itself, but the record would indicate they weren’t exactly avatars of longevity. In later decades, the shall we say Moorhead-to-Seaver ratio wouldn’t be any more overwhelming in the Mets’ favor. Now and then, a Matlack, a Milner, maybe a Mazzilli would shine; more often, you’d be saying a nearly simultaneous “hi” and “bye” to Brian Ostrosser or Brock Pemberton or Butch Benton. Even during the span when the Mets were busily producing and promoting another round of future champions — 14 members of the 1986 postseason roster rose to the majors as Mets — they had their fair share of discards. Some turned into trade bait. Some went basically nowhere. But there was always another one coming. And if you were human, you got a little extra excited to see each of them show up, show his stuff and show enough to keep you excited for the next show.

From Bob Moorhead on that first day in 1962 to Noah Syndergaard last night in 2015, there have been 360 Mets who made their major league debuts as Mets. That includes the Rule 5 guys acquired from other organizations; the Japanese imports who were rookies more on a technicality than in practice; the kids who were signed by somebody else who didn’t mind swapping them early for players they deemed necessary to obtain right away; and, most alluringly, the homegrown super prospects the Mets nurtured from first professional contract onward. Like Strawberry and Gooden way back when. Like Harvey not all that long ago. Like that.

Syndergaard isn’t like that because he was traded to the Mets from Toronto when the Blue Jays decided they had to have R.A. Dickey, a pretty desirable commodity in the wake of his 2012 Cy Young season. Dickey was how the Mets got Travis d’Arnaud, too. That kind of deal netted us the likes of Ron Darling long ago: top draft pick for Texas in 1981, Met minor leaguer by 1982, a Met taking on and setting down Rose, Morgan and Schmidt in order as of September 1983. Once you’re literally and figuratively in our system, we want you up with us; once you’re up, you’re ours. When we talked about all our young pitchers thirty-plus years ago, we didn’t hold Ronnie’s Rangers birth certificate against him.

In that same vein, we haven’t much thought of Noah as erstwhile Blue Jay property. Instead, we circled his name in the media guides of our mind as a future Met of the best kind, the kind we were looking forward to seeing ASAP, the kind whose advancement we grew impatient over. It wasn’t that Noah, 22 on his most recent birthday, was rudely keeping us waiting. He was just developing. That’s the word they use in baseball. “The Mets are developing young talent.” All teams do it. Some teams do it to great effect. Since the 2012 season began, the Mets can be said to have developed 31 players en route to MLB debuts as Mets. Some have already washed out. Some are struggling to get back. Some are momentarily on the mend.

Some are becoming the core of this team in 2015 and figure to be the core of this team clear to 2020 at the very least. This series at Wrigley Field features the cream of that crop, even if they haven’t necessarily been at their best. Noah Syndergaard is the latest in that line, the line that stretches back through Plawecki and Herrera and deGrom and d’Arnaud and Flores and Wheeler and Lagares and Familia and Harvey…clear back to Bob Moorhead.

The first appearance by the 360th Met to make a first major league appearance as a Met was as scintillating as it had to be. Syndergaard — who arrived with his very own widely disseminated nickname in tow — has stuff, all right, and he seems to know how to use it. He kept the Cubs, no pikers in the young talent department themselves, from scoring for five innings; the hand-operated scoreboard might as well have renamed the Thorboard. The kid worked himself out of trouble (some self-imposed, some inflicted on him by his defense) a couple of times. A couple of times he dominated. Eventually, he proved himself indisputably a rookie pitching for the first time against top-level competition. The Cubs couldn’t be contained in the sixth and Noah had to leave trailing, 3-0. Jake Arrieta wasn’t giving the Mets anything, so even a polymorphic reincarnation of Seaver, Gooden and Harvey would have been challenged to prevail.

The Mets went on to lose Noah Syndergaard’s big league debut, 6-1. In the present, it’s more discouraging for the hitless-wonder offense than it is for the pitcher who kept the team viable as long as he could. In the bigger picture still in the process of being sketched, we are reminded what is beautiful about rooting for a team that keeps bringing up players we’ve never seen, particularly the ones who are said to be potentially very good, even if we are initially permitted only a glimpse of their most outstanding qualities.

The beauty part is they’re probably gonna keep getting better and, until further notice, they’re gonna keep being Mets.

Coincidentally debuting the same week as Syndergaard is a podcast called I’d Just As Soon Kiss A Mookiee, the hybrid brainchild of Shannon Shark and Jason Fry. It’s half Mets, half Star Wars. I listened to half of it (you can guess which half) and I adored what I heard. You might like all of it. Listen here.

|

|