The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 8 March 2011 12:54 pm For the longest time, I adored our cats Hozzie and Avery, yet had a hard time thinking of them as “our cats”. “Our cats” meant Bernie and Casey, the cats Stephanie and I had before Hozzie and Avery. As cats will do (though nobody warns you when you plunge headfirst into petdom), Bernie and Casey eventually moved on to partake of that great bowl of Iams in the sky. Thus, Hozzie and Avery were the second generation for us. They were Cats 2.0. Their bells and whistles were impressive, and individually I fell in love with each of them from the word go (or, more accurately, from the words “hey, get off that thing!”)…but how could they be “our cats” when Bernie and Casey were that?

As I got used to the new kits in town, and as they got used to each other, I began to buy into these cats as “our cats”. I was all but there, in fact, when we got our first scanner. When the scanner went in, the old photo albums came out and Stephanie began adding familiar images to our computer.

That meant dozens of pictures of Bernie and Casey. On some weird level, it was like they were back in our lives again. How could they not be? They were right there on the screen. And if Bernie and Casey had (digitally) returned as “our cats,” what did that mean to Hozzie and Avery?

It meant they were still wonderful cats, and I loved them dearly, but it took me a little longer to totally and completely accept that they, and nobody else, were Our Cats.

I bring this up because last night I watched PBS’s Great Performances presentation of Billy Joel’s final Shea Stadium concert, which is out today on DVD (makes a great accompaniment to the excellent documentary The Last Play at Shea). As I watched, I was overcome by how quickly Shea Stadium came back to life. It was alive again in HD, and I was sure that as soon as Billy Joel told everybody not to take any shit from anybody that they’d strike the stage, clear the seats and get the place ready for when the Mets come home to face the Phillies and Cardinals.

When's the next homestand? Shea Stadium, on TV, became my ballpark again. Not in the distant past, but right now. The Mets were playing at Shea again. I was sure of it. Shea was my ballpark.

Which left Citi Field as an oddly shaped parking structure beyond the outfield fence.

As the third season of the new place approaches, I thought I’d mostly gotten over all that. I held the torch aloft for much of the first two years there was no more Shea, but I’d settled into Citi. I’d come to think of it lately as where I go when it’s not winter. Maybe not in my subconscious (I’ve had several Shea dreams in winter; in one B.J. Upton is beating us a playoff game), and maybe not automatically (one trip on the 7 line in February had me anticipating the greeting of neon men), but mostly.

True, when SNY would report on the Mets’ efforts to sign the heretofore sidelined Chrises — Capuano and Young — I was extra excited because the only footage they had of them facing the Mets was from before 2009…when they pitched at Shea. But when the network aired stories about incumbent Mets, and Citi Field served as backdrop, it felt natural enough. When I began to look forward to the Home Opener and the days and nights that will follow in 2011, I instantly went to Citi Field in my expectations.

I was all but there until last night. Then, with Billy tickling his ivories and serenading that New York state of mind, I was back at Shea. All my post-2008 protestations bubbled to the surface.

C’mon, Mets, just do it.

Just bring back Shea as it was and we’ll call it even.

Citi Field? No problem. We can use it for outfield drills and snacks.

C’mon, Mets…

I think that’s what I missed about Shea last night, that it was so wrapped up in the identity of the Mets, and vice-versa. That’s what I saw when Billy’s camera crew filmed the wide shots. I see Shea and I see the Mets at their best and most vital. I see those multiple colors and think about its singular purpose: keeping us amazed every time we walked into that place. There were no readily accessible amenities of which to speak at Shea, and until somebody invented them for other parks, it never occurred to me we needed them.

There was baseball. There was the Mets. That was it. There may not have been all that many 1969s, 1986s or 1999s, but it always felt like one might break out for a couple of innings. That kept us focused. And that kept us going.

It doesn’t feel that way at Citi Field, most likely because there is no in-house template for indefatigable enthusiasm, but also because the place wasn’t built to nurture it. It was built to sell a better burger and a $35 t-shirt. It was built to offer access to amenities. Amenities are nice. Shake Shack, et al are swell (and swell is better than swill), but damn it, the place doesn’t feel like Shea.

And no, that’s not a good thing, because it doesn’t feel like the Mets. The Mets don’t truly feel like the Mets since Shea. Perhaps they will this year. Perhaps they will feel both comfortably reassuring and new and improved once the financial clouds clear, once the state of ownership’s composition is resolved and once the front office’s wits have a chance to work their rational magic. I believe that can happen even if I don’t necessarily believe it will happen immediately.

Until then, there’s Citi Field, which I’ve settled into and appreciate in my own way more than you’d think given my recurrent bursts of longing for what was. I know what was isn’t anymore. I get it and I’m as fine with that as I can be. Yet when what was (as filmed not three years ago) bursts onto my television in stunning orange and blue and green and red, I find it impossible to not be moved to wish it was still there.

There is this, however: There is the reality that once the novelty of scanned cat photos wore off and we amused ourselves with different computer wallpaper, the aura of Bernie and Casey receded as a going fixation. Still loved them, still revered them, will always cherish them, but they mostly curled up and napped in our past. Hozzie and Avery really did become Our Cats. They are totally Our Cats.

I know that for sure because Stephanie surprised me last week and changed our wallpaper to a classic pose of Bernie and Casey sharing a chair in our old apartment. I loved seeing it. I love seeing it now, as a matter of fact. But for the briefest of instances, I looked at Bernie and Casey and felt the slightest of disappointment I wasn’t looking Hozzie and Avery, because, instinctively, those are Our Cats now.

What an interesting parking facility back there. Something like that will happen for Citi Field someday. Someday I’ll have the TV on and hear something about the “home of the Mets,” and look up and it will be a shot of Shea, and I’ll be thrown off just a bit because I was expecting, even hoping to see what I now consider the home of the Mets.

It will happen. It just hasn’t happened yet.

Cap tip to Mets By The Numbers for reintroducing the world to Iron Duke and “We Want A Hit”.

by Greg Prince on 4 March 2011 9:43 pm The Mets’ 2011 promotional schedule seeped out quietly last Saturday morning, its highlights embedded in a press release. Given that I look forward to knowing what swag the Mets will be introducing into the Metsopotamian ecosystem, I’d prefer a midweek prime time press conference live from the East Room of the White House and expect it covered on every network. Still, as far as I’m concerned, anytime is a good time to announce the coming of Magnetic Schedule Day, Lunch Box Day, Build-A-Bear Workshop Day and other days devoted to the distribution of Mets goodies.

Except the Mets aren’t having Magnetic Schedule Day, Lunch Box Day and Build-A-Bear Workshop Day…in fact, they’re cutting back on the goodies in general.

Thankfully, Collector’s Cup Night remains in place.

It took the Mets longer than I’d like to say what they’d be giving away and when we could potentially sync it to our ticket plans. Not their ticket plans, but ours. The 5-, 11- and 17-Game Flex Packs may offer flexual healing to some (each includes a bonus game), but others just want a series of what Randy at The Apple invented last month: the 1-Game Flex Pack. The Mets didn’t announce until the Grapefruit League schedule was underway that on March 14 you could buy one ticket to one game.

And that they’d be giving away in the course of the season MORE THAN 300,000 ITEMS!

You heard right…MORE THAN 300,000 ITEMS!

The 2011 Mets: Quantity, If Not Quality.

But not so fast there with the quantity, because even though the Mets’ release emphasized the giving away of MORE THAN 300,000 ITEMS! the truth is that’s a big comedown from the very recent past of 2010 and 2009, when there were nine more promotional dates apiece, thus more promotional items handed out (or sitting in boxes awaiting a loving Mets fan home). Last year’s release touted MORE THAN 400,000 ITEMS! In 2008, in a different stadium, it was MORE THAN 500,000 ITEMS!

I have to confess I hadn’t before noticed the Mets counted everything they were giving away. Then again, before this spring, there weren’t far bigger numbers being thrown around attached to stories regarding loans and lawsuits. You probably don’t notice notations about total swaggage if stories aren’t appearing every day questioning your team’s ability to remain a viable big-market entity.

Yet you look at this promotional schedule and you can’t help but wonder if the Mets are heading if not geographically but figuratively to Pittsburgh…though that might not be fair.

The Pirates give out much better stuff. So will most every team whose Web site I checked. However many hundreds of thousands of pieces will be moving doesn’t seem to be an issue for those clubs.

The 2011 Mets: Like Nobody Else.

What worries me as a fan of the New York Mets as an institution is not that they’ve scheduled far fewer giveaway dates (pending in-season additions, a couple of which usually surface) but that far fewer giveaways indicates fewer sponsors are dying to get in on the action of promoting the Mets. Not that visiting Citi Field isn’t like living inside a commercial already, but we’ve come to accept that there’s no such thing as “Helmet Day” per se anymore, that these babies are sponsored, and that somebody’s footing the bill because they see it as good business.

It seems fewer companies are looking to get their feet wet with Mets giveaways this season, or dip their toes too deeply in the Mets’ troubled waters, contaminated as their image might be by the circling financial sharks. And if such giveaway merchandise isn’t sponsored, it won’t be given away nor have a day to call its own.

The following brands were title sponsors to promotional dates in 2010 and will be again in 2011:

Budweiser, Caesars, Chevrolet, Citi, Delta, Dunkin’, Geico, Gold’s, Harrah’s, Lincoln, Nathan’s, Premio.

The following brands were title sponsors to promotional dates in 2010, but — according to the promotional schedule on mets.com — won’t be in 2011:

Build-A-Bear, EmblemHealth, Goya, HealthPlus, Natural Balance, Pepsi, Subway, Toyota, United Healthcare, Verizon.

(Goya, HealthPlus and Natural Balance each sponsored events in 2010; the others sponsored merchandise.)

Only one promotional sponsor listed for 2011, Parts Authority, wasn’t a promotional sponsor in 2010. That represents, as of now, a net loss of nine promotional sponsors since last season.

Several of those companies not plastering logos on items remain Mets sponsors for the presumable long haul. There’s still a Pepsi Porch. There is still, as far as I know, a Verizon Studio. I haven’t heard that there won’t be a Subway sign off which Daniel Murphy can scrape a questionable home run. Citi Field will likely still feel like the inside of a commercial. But the promotional schedule’s paucity (“300,000” notwithstanding) indicates a palpable inching away from the Mets in some sense. And other than Parts Authority, nobody new has stepped up to fill the giveaway void.

Is it really a void, though? Will we be, if you’ll excuse the laughable expression, suffering because we’ll have fewer opportunities to purchase tickets that will entitle us to a thing with a Mets — and a sponsor — logo? I don’t think I’ve ever had my ticket scanned at Citi Field and felt deprived because no giveaway was scheduled that day (being Fan No. 25,001 is a different matter). I’d rather there be a handful of really good ones than a load of “whatever” any year.

Are we getting closer to that ideal? Let’s take a look.

In 2010, the following was given out, one to a customer, generally to the first 25,000 customers, and the rough equivalent of the same will be given out again in 2011:

• An Opening Day premium

• A ski cap

• A plastic cup

• A gift card for use at a coffee & donuts chain

• A sports bag

• A beach towel

• Two caps

• A player bobblehead

• A drawstring bag

• A koozie (like a sweater for your beer container)

• A t-shirt

Some of the names of the items — “winter hat” has replaced “ski cap” — have changed. No doubt colors, designs and themes are up for grabs, too. Last year there was a Mets Hall of Fame cap; this year there is no Hall of Fame Day, but there is a “Cap and Hot Dog Eating Contest,” which sounds like a lot to digest (do you have to eat your cap before or after downing your frank?) — but we’ll assume two caps will be given away. There’s no Home Run Apple Bank this Opening Day, but there will be a Mr. Met bobblehead, so the “wow!” factor is a welcome wash. A Jose Reyes banner (after the trading deadline, FYI) replaces the Johan Santana koozie as accompaniment to Fiesta Latina. Some of the names of the items — “winter hat” has replaced “ski cap” — have changed. No doubt colors, designs and themes are up for grabs, too. Last year there was a Mets Hall of Fame cap; this year there is no Hall of Fame Day, but there is a “Cap and Hot Dog Eating Contest,” which sounds like a lot to digest (do you have to eat your cap before or after downing your frank?) — but we’ll assume two caps will be given away. There’s no Home Run Apple Bank this Opening Day, but there will be a Mr. Met bobblehead, so the “wow!” factor is a welcome wash. A Jose Reyes banner (after the trading deadline, FYI) replaces the Johan Santana koozie as accompaniment to Fiesta Latina.

New for 2011 is a tote bag, previously a hardy perennial, back after a one-year hiatus.

Gone from 2010? No magnetic schedule for the first time since 1996; no scarf; no water bottle; no travel mug; no Build-A-Bear; no blanket, no umbrella…and no Wright Foam Finger, though that was an All-Star add-on to get us all to vote our third baseman onto the National League squad.

As far as sponsored events — besides the Hall of Fame commencing a new gap between inductions — there is no Senior Stroll on the schedule and no Hispanic Heritage Night (also, no Pepsi Refresh Night, though that was a late addition last year). Bark in the Park will be back, but without a pet food sponsor.

Pyrotechnics Night, an unsponsored blast in 2010, is not scheduled to explode in 2011. It’s not listed, at any rate.

Cap Trade, a Subway Series tradition, returns, as does the companion ritual of fans making up addresses and phone numbers in order to nab one of the 5,000 Mets caps Chevy will trade you in exchange for your contact information (along with, theoretically, an old cap, but they’re not sticklers about that part). I’ve always assumed the idealized spirit of Cap Trade taking place when the Mets play their crosstown rivals imagines people who don’t usually attend Mets games showing up to Shea/Citi and becoming so moved by the occasion and atmosphere that they will switch allegiances on the spot. “Take this horrid piece of junk with its loathsome NY and give me that shiny new number with the splendid NY on it!”

Great symbolism. Betting it doesn’t actually happen.

My 2011 takeaway on the substance of the 2011 giveaways:

• I look forward to Ike Davis Bobblehead Night in July and sincerely hope Ike cuts a less bland ceramic figure than Jason Bay did last July.

• It’s great they’re enhancing Opening Day with Mr. Met. Opening Day would be plenty on its own.

• I’m sorry they’re skipping the Hall this year. It took so long to revive, and there are dozens of worthy candidates populating Ultimate Mets Database just clamoring for induction.

• My fridge will miss the magnetic schedule. 2010 still graces its side and I’d like it to shift into the Alderson/Collins Era, lest Jerry Manuel wander into my kitchen and insert Mike Hessman for defense.

The rest of the reduced slate could be swell or it could be lousy. When the Mets make the images available, I might be tempted to buy a ticket I wasn’t otherwise planning on purchasing. For example, if the towel features a Sistine Chapel-like rendering of the ball going through Buckner’s legs, I’m totally there on Towel Night. At the moment, all I see is the word “Towel” on a night the Mets are playing the Phillies. I hope the subliminal message doesn’t concerning throwing in the towel at the mere sight of Cliff Lee.

That there’s less slated than in past years bothers me from a State of the Franchise perspective more than a personal enrichment view. Last year’s blue and orange scarf will survive another windy April just fine, thank you. They can keep their Collector’s Cups and Cap Eating Contest. Give me a 1986 tribute (if not on the scale of what they did in 2006, which was only five years ago, then at least a little something with heart). Give me a salute to an icon along the lines of what the Cardinals are doing for Red Schoendienst and Stan Musial, the way the Dodgers are doing something for Fernando Valenzuela, the way the Giants are celebrating Willie Mays, the way the Royals are acknowledging Buck O’Neil and Willie Wilson…the way the ever-imaginitive Athletics are having not just Rickey Henderson Bobblehead Day but MC Hammer Bobblehead Day.

U can’t touch that. But U can try.

Props to the Mets for rolling out a raft of town and village nights and health awareness days and ethnic heritage nights and focused-interest theme dates every year. The Mets deserve credit for being aggressively community-minded and for supporting dozens of fine causes annually. Yay, as ever, to the Mr. Met Dash. Yay, even more, to 81 baseball games a year and winning as many of those as possible.

But would it kill them to produce a John Milner bobblehead? It’s not like the A’s are the only ones who had a Hammer.

Do a few fun and clever giveaways and keep your…I won’t call it crap, because I’d gladly accept it, but don’t try to impress me with sheer volume — or making less sheer volume sound like more sheer volume than it really is.

I’d probably press the point further, but I actually feel a little guilty asking the Mets to go the extra 90 feet for me, the customer, considering the trouble ownership is trying to ward off. When Daddy’s laid off at the plant on December 16, you don’t hand him your Christmas list the minute he arrives home, y’know? The Mets aren’t Daddy and we’re not the kids, but I do worry for their well-being. I’d like to think they’re doing their best by us given the circumstances.

That I find myself thinking of the big-market, large-payroll Mets who play in a still fresh ballpark carved by caste in these terms saddens me quite a bit. They are in a big market and they do have a large payroll and I don’t expect the Acela Club windows to be boarded up, but that feels like no more than a matter of keeping up appearances. I didn’t like the sense they looked down their nose on me as a non-fancy customer, but it never occurred to me they would lack the resources to match their high-end attitude. It makes me want to tell them, “T-shirt night? You don’t have to give ME a t-shirt. I have plenty of t-shirts. Can I bring YOU a t-shirt? I’ve got a VAUGHN 42 around here somewhere I’m not using…”

The 2011 Mets:

Maybe It’s Not That Dire Yet.

Or maybe it is.

Jason and I look in-depth at how the Mets can burnish their 50-year legacy in the just-released 2011 Amazin’ Avenue Annual. That’s just one of about 50 reasons to read the damn thing. Order it here. The 2011 Maple Street Press Mets Annual also includes contributions from each of us and a slew of really knowledgeable Mets writers. Order that one here. Both should be available at retail in the New York area as well, but don’t put off getting a copy of each. They are incredibly well worth your time and money.

by Jason Fry on 4 March 2011 9:24 am A season with 108 wins and a World Series title deserves every moment in the sun we can get it. Continuing/completing our series of guest posts at MSG.com, here’s my appreciation of Gary Carter and Keith Hernandez, two very different men who were equally important to that great team.

by Greg Prince on 3 March 2011 6:04 pm What was it like to be a Mets fan in The Year of Our Romp, One-Thousand Nine-Hundred and Eighty-Six? Since it’s one of those topics I never get tired of talking about (for at least 108 obvious reasons), I’m happy to have the opportunity to talk about it some more at MSG.com. Hope it rekindles some Amazin’ memories if you were around in 1986 or fills in a couple of blanks if you weren’t.

by Greg Prince on 2 March 2011 5:34 pm I wanted Carlos Beltran to insist that he was in one of the better shapes of his life, certainly the best of the past few years of his life. “Best shape of my life” would have been too clichéd and beyond credulity. We saw Carlos Beltran when his shape was indisputably spectacular. I would have settled for “I’m in the best shape of my life since 2009 began to go to hell.” That would have been plenty good.

Whatever he said, I wanted Carlos Beltran to find his legs and stand his ground. First he’d stand it, then he’d run it, then gallop it en route completing a circuit that would have him owning it as he did before the middle of 2009, before his right knee went all wrong. I wanted Carlos Beltran to defy time and anatomy and be as much the center fielder he could be, if not completely the center fielder he used to be.

As of Monday, that bit of spring romanticizing flew over the wall. Carlos did the chivalrous thing. He turned his center field glove into a cloak worthy of Sir Walter Raleigh. Beltran spread it over a puddle of mud and allowed Angel Pagan to cross over safely from right field. Then, Carlos gathered up his cloak-glove, shook off the schmutz and trotted over to where Pagan was set to stand in order to learn his new position.

Or he will as soon as that darn knee is capable of taking on his next personally unprecedented challenge.

Twilight closes in now on Carlos Beltran’s Met tenure, approaching irresistibly as it did within the past decade on Mike Piazza and Pedro Martinez, two other imported stars of Beltranian magnitude. I hated that it had to happen to them, but understanding inevitability was involved, I sort of relished the process. I anticipated the pushback from the veterans involved. I stood and cheered on those occasions when each told time to wait outside for another couple of innings, I’m not done here yet. I looked for every possible angle that would allow my illogic to sound just a little more rational. I wanted to believe that maybe Mike wasn’t getting too old to crouch, to catch and to hit six games a week. I wanted to believe, somehow, that two-and-a-half injury-riddled, tease-wracked season of Pedro were an aberration, that deep down he was still the Pedro Martinez and could turn it on again anytime I wanted.

Piazza’s decline was at first gradual, then undeniable. Everything he did in 2005, the last season of his seven-year Mets contract, looked harder than it had before — and Piazza never made anything look easy (save for coming through in the most dramatic of circumstances, which came second-nature to him). Martinez was trickier to track as he attempted to pitch like Pedro in 2008. After his umpteenth Disabled Listing, Pedro always seemed one inning away from being something proximate to his old self. Problem was most nights that inning was the first inning; he pitched 20 of them and gave up 23 earned runs within them. Get Pedro to the second, and he’d emerge unscathed. From a 10.35 ERA in the first inning, his effectiveness yielded a 1.80 in the second and a 0.90 in the third.

Then came the fourth inning and mortality’s ugly head reared via an ERA of 5.12. The earned-run numbers grew only more disturbing from there. Pedro Martinez rarely made it past six innings in his final Met year, yet I always clung to the hope that he would. Same for Mike at his Shea end. Why couldn’t Mike Piazza give us in 2005 what he gave us as a matter of course in 2000? Even in 2002? He could do it a couple of times a week. Why not a couple more?

Because time could not be kept waiting in the players’ parking lot forever. It had come to pick up Mike in 2005, just as it would Pedro in 2008, just as it promises to exit the Grand Central by the end of 2011 (if not sooner) to give Carlos Beltran his ride to somewhere else.

Beltran’s days in the majors may not necessarily be over when he’s through being a Met. They probably won’t be. There is life after Mets, as unpleasant as that is for us to recognize. Mike Piazza logged two seasons on the West Coast. Pedro Martinez filed a couple of very successful months in a Philadelphia uniform in 2009. Beltran’s younger than both were when they departed Flushing.

But Piazza, despite being yanked to a new and strange position for a spell in his penultimate Mets campaign, never exactly gave up being a catcher. And Pedro didn’t suddenly volunteer to attempt to stabilize the Mets’ manic middle relief corps. They squeezed every bit of light out of their starring roles in their last go-rounds. Willie Randolph’s misplaced sense of occasion is all that kept Mike from nine full innings in his final afternoon in orange and blue. Martinez threw himself into the seventh inning on his last Shea night for only the fourth time in his twenty ’08 starts. Each man took about a dozen deserved bows on the way out. We wouldn’t have let them go in any other fashion.

Carlos Beltran now steps aside early. Maybe he’s a permanent right fielder for as long as he’s part of the Flushing scenery. Maybe the bizarre configuration of corporately sponsored geometric tics that give us Porches and Zones and a prospective nightmare for a neophyte right fielder on the cusp of turning 34 will — combined with a theoretical rediscovery of his legs — reverse eventually what seems permanent and reasonable at present. Maybe Pagan, by necessity, shifts back to patrolling Citi Field’s most perilous corner (which he, unlike Beltran, has done before). Maybe right field proves plenty conquerable for Carlos, someone who has spent so long as one of the premier center fielders of his generation, and center becomes just one of those positions an aging superstar used to play. Maybe, because these are the Mets we’re talking about, Beltran goes back on the DL and whatever future he has remaining is as a lavishly (lavishly) compensated pinch-hitter…assuming everybody in a Mets uniform continues to receive his compensation as contracted.

The good of the team and however unready Carlos’s right knee is for center dictated what happened when Beltran went to Terry Collins and Collins called on Pagan and the three of them agreed on the new outfield alignment. Beltran in right is the right thing to try. It’s not the wrong thing, anyway. Carlos Beltran knows his knee better than Mets management and medicine men claimed to know it in January 2010. He knows it a helluva lot better than I do. There’s a lot of real estate in Citi Field’s center field, and two good legs are preferable for anyone planning to occupy it. And if converting himself into a right fielder helps Beltran extend his baseball playing and earning potential in the years after 2011, more power to him. A person’s gotta do what a person’s gotta do.

But I still wish he was standing his ground. I still wish he was stubborn and defiant and a self-proclaimed center fielder. I wanted to see Carlos Beltran incrementally return to form as he seemed to be doing late last summer. It was clear he knew how to play center, that he hadn’t forgotten, that his instincts would never fail him…but that his legs were having none of it. Then they began to cooperate a little. Then a little more. Then I began to stare hard and see the Carlos Beltran who arrived during Mike Piazza’s final Met season and who excelled while Pedro Martinez alternately healed and rehabilitated.

Then Beltran couldn’t finish 2010 in one piece and has yet to begin 2011. That’s not a center fielder. Not now it isn’t.

There are men who play center field (“oy, the way Keith Miller played…”), and then there are Center Fielders, the kind who make great catches and land among lyrics. Beltran was in the Upper Case group, a CF who took responsibility for every fly ball and every line drive — the kind who took command of the outfield. Beltran was so much a Center Fielder that his presence compelled another authentic Center Fielder, Mike Cameron, to rush to learn right field in another St. Lucie spring not so long ago. Cameron was a dynamite defender for the Mets in 2004, his first year at Shea. Once he established himself as a big leaguer, his managers wouldn’t have placed him anywhere but center. He replaced Ken Griffey in Seattle, and defensively nobody could complain. Even Art Howe wouldn’t have thought to move Mike Cameron out of the middle of things in 2004, and Art Howe thought Mike Piazza would make a splendid first baseman.

Then came Carlos Beltran, every bit the Center Fielder Mike Cameron was, plus a more accomplished offensive threat, plus a way better-paid employee of Sterling Mets. The 2005 Mets possessed two CFs, but the scorecard accommodated only one 8 at a time.

Carlos Beltran was signed to be The Man. Mike Cameron played right field. He didn’t want to. He didn’t particularly hide his displeasure about it and he couldn’t disguise his instinctive intentions when the territories blurred. The ultimate manifestation of what might happen when you put a real Center Fielder in center and a real Center Fielder in right occurred on August 11, 2005, when David Ross’s sinking line drive, falling fast in mid right-center at Petco Park in San Diego, attracted the attention of two Center Fielders. Beltran came at it from our left. Cameron came it at from our right.

Their faces met in the middle. It was gruesome. Cameron’s Mets career was over. Beltran’s was shaken. Both survived and have since gone on to collect four Gold Gloves between them for their work as Center Fielders. Neither has played as much as a pitch at any other defensive position in the seasons following their collision.

We speak of Beltran’s center field term in the past tense, that he was a Center Fielder, but that’s probably a mistake. It’s not so much that he’s likely to snatch the job from the mitts of his faithful and skilled protégé Pagan. It’s that if you’re a Center Fielder, it doesn’t appear you stop thinking like one. Beltran has been all over center field. He played it deep (far deeper than Cameron) and made his plays. Carlos’s grace may have obscured his hustle, but without making a big Jim Edmonds deal about it, he dove where the terrain grew shallow and he challenged fences when pasture turned into track. He was an every-damn-ball Center Fielder. It’s impossible to think that because we write his name next to a 9 instead of an 8 that he will take on a new self-identity.

He’s Carlos Beltran, best Center Fielder in the history of the New York Mets. I long to see him be that and do that for one more season. It appears I’ll have to settle for remembering that he was that and that he did that…and accept that that might very well be that.

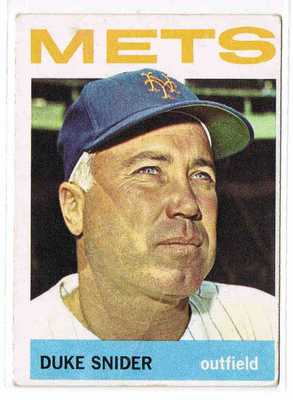

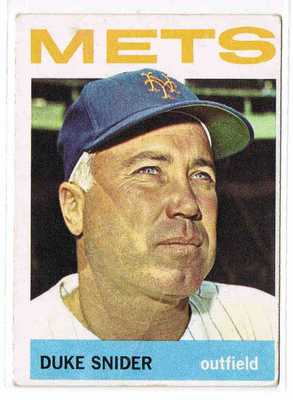

by Jason Fry on 28 February 2011 11:14 pm Duke Snider was hugely talented, agreeably and disagreeably human by turns, and essential to the myth of the Brooklyn Dodgers — for the move west from Ebbets Field to the other side of the continent threw his career into permanent decline, almost as if the Duke of Flatbush had lost his royal powers when he was exiled.

It was a cruel bit of irony that Snider should have been the one undone by replacing a B with an LA on his cap. He was from Los Angeles — straight outta Compton, as it would be put later in a rather different setting — and at first he welcomed the chance to come home. But where Ebbets Field had invited lefty sluggers to bash the ball onto Bedford Avenue, the converted Olympic track-and-field stadium known as Los Angeles Coliseum promised them doom: To Snider’s consternation, it was 440 to right center. Snider had hit 40 or more home runs for five years running in Brooklyn, and was just 31. His first year in L.A., he hit 15. In shockingly short order (helped along by a bad knee), he became a part-time player, then a Met, then a Giant in a bit of unhappy farce, and then retired at 37. (Tip of the cap to our pal Alex Belth for passing along an excellent Dick Young retrospective from Inside Sports about Snider. You can read it at the bottom of this Bronx Banter post.)

We remember Snider for the memory of him as a Dodger, and for that lone campaign as a Met. His 1964 Mets card captures him perfectly, in oversaturated Topps colors: silver hair, ice-blue eyes, the penetrating gaze and granite chin of a captain of infantry or industry. Yet I’m torn when I think of those old New York players and their victory laps around the Polo Grounds. They bind the Mets more closely to the Dodgers and Giants and Yankees than blue and orange and pinstripes already did, it’s true — and I’ll always be a sucker for mystic chords of memory. But the likes of Hodges and Woodling and Zimmer and Snider and Berra and even Casey himself were brought to New York not because they could help their new club — with the exception of the luckless Roger Craig, they did very little of that — but, as Greg noted earlier, to be sideshows meant to distract the paying customers from how shabby the on-field product was. (This self-defeating nostalgia had an encore with Willie Mays’s farewell tour in 1972 and 1973, but I can forgive Mrs. Payson that one: What’s owning a baseball team for, if not trying to stop time for your favorite player?) The Mets got better when they outgrew serving as a rehearsal for Old Timers Day for the Boys of Summer and their ancient adversaries; in paying homage to the 1950s Dodgers and Giants and Yankees who wound up in orange and blue, we should remember that the franchise’s early days would have been less pathetic with fewer such cameos. We remember Snider for the memory of him as a Dodger, and for that lone campaign as a Met. His 1964 Mets card captures him perfectly, in oversaturated Topps colors: silver hair, ice-blue eyes, the penetrating gaze and granite chin of a captain of infantry or industry. Yet I’m torn when I think of those old New York players and their victory laps around the Polo Grounds. They bind the Mets more closely to the Dodgers and Giants and Yankees than blue and orange and pinstripes already did, it’s true — and I’ll always be a sucker for mystic chords of memory. But the likes of Hodges and Woodling and Zimmer and Snider and Berra and even Casey himself were brought to New York not because they could help their new club — with the exception of the luckless Roger Craig, they did very little of that — but, as Greg noted earlier, to be sideshows meant to distract the paying customers from how shabby the on-field product was. (This self-defeating nostalgia had an encore with Willie Mays’s farewell tour in 1972 and 1973, but I can forgive Mrs. Payson that one: What’s owning a baseball team for, if not trying to stop time for your favorite player?) The Mets got better when they outgrew serving as a rehearsal for Old Timers Day for the Boys of Summer and their ancient adversaries; in paying homage to the 1950s Dodgers and Giants and Yankees who wound up in orange and blue, we should remember that the franchise’s early days would have been less pathetic with fewer such cameos.

Young’s retrospective about Snider is itself thick with nostalgia — in it, the Duke and Pee Wee and Oisk ride again, celebrating at Borough Hall and carpooling from Bay Ridge and jawing with sportswriters and fans and opponents and each other. But Young doesn’t shy away from Snider’s gaffes, like telling Roger Kahn he played for money or shouting that Brooklyn’s goddamn fans didn’t deserve a pennant.

Snider caught hell for that last one, at least until he hit his way back into their good graces. Thinking about that, I was drawn to today’s bit of Mets news: Carlos Beltran’s preemptive declaration that he would play right field, sliding over for Angel Pagan. “In my heart, I still feel that I can play center field,” Beltran told reporters, “but at the same time, this is not about Carlos — this is about the team.” You could almost feel the disappointment as the assembled beat writers watched a juicy spring-training storyline disappear with a minimum of fuss and strife; by contrast, Terry Collins’ relief was practically palpable.

Beltran, being Beltran, will get little praise from a certain segment of the fan base for putting the team above his own pride. (Let me guess: His agent put him up to it so he can extract more value from somebody.) I’ve given up trying to convert those who can’t help but see Beltran as embodying all that’s supposedly wrong with baseball today. They dislike one of the franchise’s greatest players for making the game look easy, for not throwing tantrums when he fails, for not trusting his knee to the Mets’ idiot doctors and dithering front-office cheapskates, for having Scott Boras as his agent, for not managing to hit an impossible 12-to-6 curve when geared up for a fastball, for attending a charity meeting about building schools in Puerto Rico instead of going to Walter Reed, for being injured, for being rich, for being Carlos Beltran.

Here’s what I wonder: How would Duke Snider be treated today, in a world in which salaries have grown astronomically, our demand for information is voracious and spastic, and a reflexive cynicism threatens to pervade everything? Snider’s per-year earnings as a ballplayer maxed out at $46,000. That’s about what Carlos Beltran will make in his first 3 2/3 innings of 2011. If they could trade places, would Snider’s sad decline from a knee injury have been blamed on his lack of toughness instead of a Yankee Stadium drain? Would his home-run outage in L.A. have been attributed to a lack of passion rather than a reconfigured park? Would Duke Snider have been a hero if he’d made $46 million instead of $46,000?

Two great preseason publications are out, each with contributions from Faith and Fear and other Mets writers you know and love. Get your hands on Amazin’ Avenue Annual here and Maple Street Press Mets Annual here.

by Greg Prince on 28 February 2011 1:30 pm As has become annual custom here on the day following the night the Oscars are presented, the Academy would like to pause for a moment to remember those Mets who have, in the baseball sense, left us in the past year.

Joaquin Arias, 2010

Earth to Jerry: The game counted. It was 1-1. We could have used our two best players to theoretically help win it. That would have been nice. Instead, it was six innings of Mike Hessman and Joaquin Arias — fine fellows, no doubt, but not David Wright and Jose Reyes in a 1-1 game. Not even close.

—October 4, 2010

Eddie Kunz*, 2008

Evans, 22, and Daniel Murphy, 23, are the co-starting leftfielders. Eddie Kunz, 22, is the closer. These arrangements may be temporary or they may be a harbinger of what is to come. Either way, it’s going on right now in the midst of what is still, despite recent evidence to the contrary, a pennant race.

—August 3, 2008

Andy Green, 2009

Yet here we all were — us, the Mets and Andy Green — doing what seemed to come naturally. For us and the Mets, it surely wasn’t 2006 anymore, but in our souls, it’s never 2006; it’s almost always 2004 or 1977 or some year like that. For Andy Green…well, he was just happy to be here. Sunday he had been a Buffalo Bison. Monday, like so many in his herd, he was grazing a big league spread in a big league clubhouse. Why shouldn’t Andy Green be happy to be here? And why shouldn’t we be happy to have him? We would make the best of Andy Green because we knew how to make the most of moments exactly like this one.

—August 18, 2009

Carlos Muñiz, 2007-2008

You know you’re going well when your bullpen, previously sponsored by Much Maligned — I had gotten to thinking the Mets’ Much Maligned Bullpen was its official name — is a freestanding entity of valor and accomplishment. At the end of the game yesterday, DiamondVision announced the star of the afternoon was the combined corps of Muñiz, Heilman, Schoeneweis and Wagner for their five hitless innings. A cheer went up. Ten minutes ago, Carlos Muñiz was the most popular member of that crew and that was only because nobody knew who he was.

—July 13, 2008

Frank Catalanotto, 2010

I’d like to believe the same man who can get through to baseball’s most notorious free swinger has more on the ball than threatening to bat Jose Reyes third and actually batting Frank Catalanotto fourth.

—April 19, 2010

Anderson Hernandez, 2005-2006, 2009

Gosh, Saturday’s game was so much fun, making it that much more of a shame that we had to trudge back to our usual humdrum lives so soon again. What, Angel Pagan couldn’t have kept the ninth-inning rally going for the power-hitting Anderson Hernandez, he who has the distinction of bopping the Mets’ 6,000th home run? (That’s 6,000 in franchise history, not in one game — that, as they used to say on SportsCenter, would be a record.)

—September 13, 2009

Mike Hessman, 2010

Hessman rips into the third pitch he sees from Romero and becomes the only Met to fully comprehend that Citizens Bank Park is a bandbox. It’s a three-run homer, and the Mets are within 7-5. Get a guy on, and Reyes up, and…I should point out that I didn’t believe for a second this would work out. Not consciously. Not seriously. In fact, I couldn’t even get the kinks out of the You Gotta Believe reflex completely because just as I earlier imagined Bo Diaz, now I was whisked into the land of Prentice Redman. Anybody else remember Prentice Redman?

—August 7, 2010

Fernando Nieve, 2009-2010

Given the tenor of what enshrouded the Mets from Friday, I think we can catalogue Nieve’s 6⅔ innings as the best, most crucial start we’ve seen since Johan in Game 161 last September. It was definitely an effort that won’t keep us all awake and drinking later tonight.

—June 13, 2009

Sean Green, 2009-2010

I must confess that as Sean Green faced Pujols, I wasn’t just confident he would give up a death blow; I was not altogether rooting against it. I’d felt like a tool for taking these Mets so seriously so late in their decline, at least a month after they revealed themselves incapable of keeping up with the Phillies let alone the Giants. C’mon Albert, I thought after Green hit DeRosa with the bases loaded to make it 8-7. Just pull the plug on us already, you bastard. Just put us out of our misery.

—August 7, 2009

Gary Matthews, Jr., 2002, 2010

In 2006, his free agent walk year, Gary Matthews, Jr., suddenly became a star. He made hellacious SportsCenter catches for Texas, batted. 313 and scored 102 runs. Then he scored an unbelievable contract based on his brilliant timing, signing with the Angels for five years and $50 million. Three of those years are over with. None of the first three much resembled his 2006. Then again, not much of our last three have resembled our 2006. And now we get his next two years. Hmmm…maybe that’s what attracted Omar to Gary Matthews, Jr. They both peaked four seasons ago.

—January 22, 2010

Elmer Dessens, 2009-2010

Nieve didn’t have it. Recently repurposed long man/money sponge Oliver Perez didn’t have it, either. By the time we got to Elmer Dessens, there was nothing left to have. The Mets could dress up as New York Cubans but there was no disguising that they had no pitching for the first four innings Saturday night. Dessens, Igarashi and Mejia gave up no runs over the next four, but by then the horse was galloping south on I-94 and Mrs. Lincoln had forgotten how much she enjoyed the play. Those were, however, sharp uniforms.

—May 30, 2010

Raul Valdes, 2010

They turned the farcical into the nearly tragicomic. It wasn’t surreal because nobody could have dreamed up the scenario of Lopez, the grand slam hitter from Friday, pitching to Raul Valdes, the grand slam pitcher from Friday. Valdes gets on and then gets thrown out trying to stretch an infield single that was thrown away into a double. I’m sitting on the couch yelling at Valdes for getting caught. It doesn’t even occur to me that this is Raul Valdes who probably hasn’t touched first base since he was six, and the whole irony of Lopez as the guy who slammed Valdes the night before is lost on me.

—April 18, 2010

Alex Cora, 2009-2010

Well, that wasn’t so bad. I mean, the Mets lost. To the Yankees. Because Alex Cora inexplicably threw a ball to Jose Reyes’s invisible twin brother on the edge of the outfield grass, and because Elmer Dessens was Elmer Dessens. And because they couldn’t hit, not even against Javier Vazquez. How is that not so bad? Because I’d expected much worse.

—May 21, 2010

Omir Santos, 2009

The system installed to see to it that bad umpiring could be overruled by modern technology had a redemptive flavor to it as well. When Omir Santos unleashed that lethal short swing on Jonathan Papelbon in the ninth, I thought it was too much to ask for it to go out. Then I thought it was too much to ask for it to be ruled to have gone out even though it did. “We always get screwed on these calls,” I informed Stephanie who is quite aware of our track record in call-screwage. Ah, but home run replay. That’s a relatively new twist on a formerly rancid cocktail of arbiter incompetence. Even Joe West can watch TV. Even Joe West and his merry men — including Paul Nauert, ball cop — could see Santos’ shot landed above the magic barrier that separates homers from doubles before bouncing back to earth. It took a while, but fingers were twirled and runs were assigned. Omir Santos: short stroke, long trot.

—May 24, 2009

Mike Jacobs, 2005, 2010

Benson and Floyd and Victor and all of today’s disappointment retreated — still there, but at a decent remove — and what was left was Mike Jacobs, who went from trying to catch his breath in the batter’s box to mashing one into our bullpen (Hey, cool! He’ll get the ball!) before you could say “Tricia’s from Ditmas Park, and IT’S HER BIRTHDAY!” After the inning I grabbed the TiVo remote and bi-doop-bi-doop-bi-dooped my way back so I could watch Jacobs levitate around the bases again, then one more time because I’d enjoyed it so much the second time.

—August 21, 2005

Henry Blanco, 2010

The Mets were leading 6-3 at this point of the nightcap. While the carnitas were being roasted or folded or whatever it is that makes them marvelous, I looked up at the monitor. The bases were full of Mets: Blanco on third, Pagan on second, Castillo on first. Reyes was coming up with one out. He took one ball then slapped a grounder to Dodger shortstop Jamey Carroll. Carroll threw home. Blanco appeared to be a dead duck. As I calculated the situation-to-be — two out but the bases still loaded for Jason Bay — I saw the throw get away from catcher A.J. Ellis. Blanco, suddenly live gazelle instead of dead duck, was safe. It was 7-3 Mets. Yet it was so much more. It was the jolt I didn’t realize I was dying for, more than I was dying for warmth, more than I was dying for carnitas. When Blanco slid across the plate successfully, I didn’t think. I just jumped. I jumped in the air and clapped. Then I did it again. As I was jumping and clapping, I was yelling, something along the lines of “YES!” and “ALL RIGHT!” and, in case the Taqueria cook wasn’t sure, “HE SCORED!” It wasn’t what I was yelling, it was that I was yelling. Yelling and clapping and jumping. It was instinct. It was Mets fan instinct. It had been missing for so long that I instantly savored the realization of what had just happened.

—April 30, 2010

Nelson Figueroa, 2008-2009

We thought about the perfect game, the no-hitter. We thought about it, hoped for it, knew it wasn’t coming, nodded our heads when it didn’t arrive. I bet Nelson Figueroa did all that too. And I bet he knew there wouldn’t be 27 up and 27 down. After all, he knows how things work around here. He knows because as a kid he was one of us, and because now he is — at long, long last — a New York Met.

—April 11, 2008

Chris Carter, 2010

I do know Chris Carter thinks New York fans are “intelligent,” “passionate,” “understand the game” and “deserve a winner”. That’s nice of him to say, and I got the sense he believes it. Talk to Chris Carter for a few minutes, and you get the sense he doesn’t say anything he doesn’t believe.

—October 2, 2010

Rod Barajas, 2010

It happens every year. It’s baseball. It’s funny that we almost never notice how common it is. We go from barely aware of Rod Barajas to relatively obsessed with Rod Barajas to not batting an eye when Rod Barajas is dispatched from our midst. We care about Rod Barajas until we don’t, or until he gives us little we consider worth caring about. When Rod Barajas was outhomering every catcher in the National League, we were smitten. When he stopped homering and then stopped hitting altogether, we lost interest. When he went on the DL for nearly a month after straining his oblique, we weren’t all that heartbroken, bastards that we are. We wanted to see Thole. We wanted to see hope. We had seen enough of Rod Barajas.

—August 24, 2010

Hisanori Takahashi, 2010

First, it wasn’t easy. Jason Michaels brought home a run. Now it wasn’t a combined shutout anymore. Now it wasn’t quite so breathable. It was a one-run game, one closer fill-in gone, the other not on the most solid of ground. Two on, one out. Yet the Mets’ world did not come crashing down on Hisanori Takahashi. He had to nail down two outs and he did (weird balls & strikes umpiring helped, but it’s been known to hurt, so we won’t question Angel Campos too harshly). Angel Sanchez popped up and Tony Manzella looked at strike three and that was that in a good sense. No closer per se, but when BTO blares, nobody much notices that it was an understudy instead of a star takin’ care of business.

—August 28, 2010

Fernando Tatis, 2008-2010

The mind ran away, as it’s entitled to after that rarest of good nights…Tatis can hit. Tatis can stay. Tatis can be the extraordinarily capable supersub this team is missing. Tatis can be the wise voice this team is dying for. Tatis can be Ray Knight for a new century, taking the pressure off our stars who are too callow or too reticent or too insolent or too dim to really handle all these reporters who surround you after every game, win or lose. Fernando Tatis is just what we need! The mind comes back, realizing it just pulled a long thought foul. In the meantime, I’m glad someone associated with the Mets is happy and he knows it and he really wants to show it.

—May 28, 2008

Jeff Francoeur, 2009-2010

It would enhance this game’s classic bona fides if indeed Eric Bruntlett had extended himself as heroically in the bottom of the ninth against Jeff Francoeur as Francoeur had against Bruntlett in right in the top of the ninth when he channeled Ron Swoboda. The Phillie second baseman, however, just happened to be in the right place while every Met who mattered found himself in the wrong place. The two runners in motion would have been better off standing still, while Francoeur’s mistake was suddenly developing a knack for making contact.

—August 24, 2009

John Maine, 2006-2010

Fourteen strikeouts. Overpowering. Untouchable. And 23 outs without a hit. The phrase I kept coming back to was “All right, John — let’s go.” I heard myself saying it in the fourth after a pitch, so I just kept saying it. “All right, John — let’s go.” And John went as long as he could. He still hasn’t given up anything like a legitimate base hit. The dagger in the heart of history of course rolled 45 feet and not foul. When Paul Who?ver half-swung, half-bunted and totally fucked with our hearts, time kind of stopped. It wasn’t going to get to Wright and Wright wasn’t going to get to it and it wasn’t going to cross over a line and this nonentity of a third-string catcher actually had the nerve to run instead of doing what big-shot ballplayers do when they’re not sure where a ball is going. Doesn’t Paul Who?ver know to just stand there and get thrown out? With John Maine’s 115th pitch, he was removed (I was already envisioning him lifted after eight regardless of no-hitter because Pitch Count Is All). I knew what was next. I knew we had to stand up and applaud Maine’s brilliant stab at Met immortality. Then I knew we had to continue as he walked to the dugout. But I didn’t have it in me. I clapped weakly and trudged away. I hadn’t been to the bathroom the whole game (who’s superstitious?) but mostly I had to go hit something (the vacated cheesesteak stand did nicely) and slam something (men’s room door) into a wall lest I moisten anything (like a tissue).

—September 30, 2007

Pedro Feliciano, 2002-2004, 2006-2010

Pedro kept showing up. Pedro kept getting the call and, more often than not, Pedro kept getting the key out. Maybe it was only one out, but Pedro got his man. One man in particular, who literally towers over Pedro Feliciano, was made to look small in his presence. That alone was awfully impressive in an otherwise depressing campaign. Ryan Howard has six inches and 70 pounds on Pedro Feliciano if you believe official listings. Goodness knows you couldn’t trade Pedro Feliciano for Ryan Howard. But would you trade Pedro Feliciano knowing Ryan Howard is looming somewhere on your schedule over and over — and over and over — again? When the Mets dismantled most of their disaster-laden bullpen after 2008, they left one mainstay in place. No more Heilman. No more Schoeneweis. No more Smith or Sanchez or Ayala. But yes, more Pedro Feliciano. Always more Pedro Feliciano.

—November 18, 2009

*At last check, former supplemental first-round pick Eddie Kunz was still in the Mets organization. But after not appearing in a major league game for two consecutive seasons; posting ERAs of over 5 these past two full minor league campaigns; spending all of 2010 at Double-A Binghamton after spending all of 2009 at Triple-A Buffalo (while the Mets’ bullpen was in its usual state of flux both years); being removed from the 40-man roster last fall; no longer pitching under the auspices of the general manager who drafted him high and might have had a stake in his development; and receiving no invitation to major league camp this spring…well, his inclusion here as a former New York Met does not seem inappropriate. Designation subject to change should Kunz reverse his trendline, which is both possible and, of course, desirable. Kunz won’t turn 25 until the second week of April.

UPDATE: Eddie Kunz was traded to the Padres on March 29, 2011. So there ya go.

Two great preseason publications are out, each with contributions from Faith and Fear and other Mets writers you know and love. Get your hands on Amazin’ Avenue Annual here and Maple Street Press Mets Annual here.

by Greg Prince on 27 February 2011 11:00 pm Most dignified-looking Met: Duke Snider. That gray hair gets them. If he offered to sell you the Brooklyn bridge you’d be certain he owned it.

—Leonard Shecter, New York Post, 1963

“I think Casey was referring to the fact that when I was 29, I’d have 10 years in the league, but of course, he mangled the quote. Even he probably didn’t remember it.”

—Greg Goossen, Los Angeles Daily News, 2009

The confluence of events leads us to contemplate two former Mets who, at first glance, had nothing to do with one another. Duke Snider was one of those Hall of Famers whose “NEW YORK N.L.” notation can be viewed by those not afflicted by a Metsian mindset as a footnote to a brilliant career forged in another uniform. Greg Goossen, on the other hand, played most of his baseball in our favorite clothes but didn’t play it terribly long or with particular distinction. Yet we consider these two Mets at this moment because fate saw fit to bring their lives to an end on the same weekend.

Snider and Goossen were both born in Southern California and both died there, at ages 84 and 65, respectively. They were not contemporaries, having just missed each other in a manner of speaking. Snider’s long major league tenure ended in 1964, a year before Goossen’s began. Duke played until he was 38, though to look at him in his twilight, you would have guessed he edged closer to Hoyt Wilhelm/Jamie Moyer territory. Goossen came up in ’65 as the Mets’ fifth-ever teenager.

Age, though, may be where we find the common ground between the two men whom we mourn.

Duke Snider, post-Flatbush, was a 1963 Met just waiting to happen: he used to be an outstanding National Leaguer and he did most of his standing out in Brooklyn. First Mets president George Weiss constructed his initial roster with an eye on distracting the paying public. No way the ’62 club was going to be any good anyway, so why not stock it full of as many (faded) Senior Circuit stars as could be had, and if they happened to be old Bums, all the better. Thus, the first Metropolitan edition included Gil Hodges, Roger Craig, Clem Labine, Charlie Neal and Don Zimmer; the 1962 Mets could have been the 1956 Dodgers, save for the inevitable deterioration of the human condition.

Then came the Duke, the big bopper in Brooklyn through their incandescent ’50s stay, a lesser light as time (and the Los Angeles Coliseum’s dimensions) took their toll on him in L.A. The Duke Snider the Mets signed just ahead of the opening of the 1963 season was only in name and fame the same slugger who hit more home runs than any other individual in the 1950s. But these were the Mets, and name and fame was good enough.

So was Snider, actually. In modern terms, consider his 1963 a prototype for Gary Sheffield’s last-minute arrival in 2009 (except more fans were happy to see the Duke). Strapped for talent, Casey Stengel played him in the outfield too much — sort of like Jerry Manuel with Sheffield — but he produced a few certifiably memorable moments, including a milestone homer. Just as Sheff joined the 500 Club in Citi Field’s first week, Duke hit No. 400 as a Met, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, though the shot that survives in memory and kinescope footage was the one before it. The Mets trailed the Cardinals 2-0 at the Polo Grounds in the bottom of the ninth on June 7. With one out, Rod Kanehl on third, Ron Hunt on second and Diomedes Olivo on the mound, the Duke swung and sent No. 399 soaring over the right field fence…same as he might have taken aim at Bedford Avenue once upon a time. The Mets prevailed 3-2 in their only Duke-off win.

Snider totaled 14 home runs as a Met and served as their lone All-Star representative in 1963. Unbeknownst to everybody 48 years ago, he also posted the second-best WAR on the club, behind only Hunt. Toward year’s end, the unthinkable occurred and the Duke of Flatbush was given a Night of his own at the Polo Grounds, replete with a car, a golf cart and trip for two anywhere he wanted in the world. The occasion was warm and fuzzy enough, but overall, his Manhattan “homecoming” wasn’t everything Duke could have wanted. The Mets were a 51-111 enterprise, Casey Stengel was grabbing a few winks on the bench and Snider wasn’t getting any younger. He wanted out and, on the cusp of the 1964 season, his wish to go to a contender was granted — Duke Snider was sold to the Giants.

Which was a lot weirder than a Brooklyn Dodger becoming a New York Met, but at 37 and with his skills clearly receding, even future Hall of Famers couldn’t be choosers.

As Snider was escaping the Queensbound Mets, the emphasis for the third-year franchise was changing from familiar veterans with little left to kids whose eventual limit may very well have been the sky. With the Mets 140 games under .500 after two years, there was no time like the present to find out how high those youngsters’ ceilings might rise. In the spring of 1964, Stengel stirred to proclaim the Youth of America was en route to beautiful new Shea Stadium.

Hardly anybody was more youthful than catcher Greg Goossen in Shea’s first seasons, though he was hardly alone among those barely old enough to enjoy an ice cold Rheingold after games (and not old enough to vote in anything but an All-Star election). Seven members of the 1965 Mets played big league ball before turning 21. Hardly any of them was truly battle-ready. Goossen wasn’t ripe yet, but he gave a decent enough accounting of himself upon his cup of September coffee, batting .290 and reaching Bo Belinsky at Connie Mack Stadium for his first homer.

Goossen would be back in the minors most of 1966 until September, when he cracked one more homer but hit a scant .188. Wes Westrum kept him on the roster the first month of 1967, and brought him back from the minors in July, but Greg’s progress was moving in reverse: .159 BA/.216 OBP/.174 SLG in 74 plate appearances. He lasted three months under Gil Hodges in 1968 and didn’t impress. Just before the 1969 Mets began to coalesce in St. Petersburg, Goossen, 23, was traded to the expansion Seattle Pilots for Jim Gosger.

This may be the longest anyone has ever written about Greg Goossen’s Mets career without mentioning the one thing it seems everybody remembers, so let’s mention it. It comes in slightly different shapes and flavors, with the ages sometimes fudged for fluidity’s or accuracy’s sake and sometimes without the proper setup — namely that in the spring of 1965, Casey Stengel was touting the potential of his many youngsters, including bonus baby Ed Kranepool, who, Casey declared, was 20 but had a chance, ten years hence, to grow into a star.

Let Jack Lang, via New York Mets: Twenty-Five Years of Baseball Magic, pick it up from there.

“‘And we have this fine young catcher named Goossen who is only 20 years old, who in ten years has a chance…’ Stengel stopped. For a split second he was stumped. Then he continued in classic Stengelese, “‘in ten years he has a chance to be 30.’”

Greg Goossen had more in store for himself beyond simply aging. He was one of the few Seattle Pilots there ever were (joining most of the rest of them in Jim Bouton’s Ball Four) and then, after following them to Milwaukee (and finishing up as a Washington Senator) in 1970, he went Hollywood. Goossen enjoyed a lengthy career as Gene Hackman’s stand-in, nabbing more than a dozen screen credits for himself along the way.

Still, Casey wasn’t altogether wrong. Greg Goossen did turn 30 ten years after he was 20 (even if he was only 19 when Stengel offered the most oft-told version of his forecast). The kid had a future…it’s just that baseball wasn’t much a part of it. The Youth of America, however, yielded a few tasty plums, per the Ol’ Perfesser’s prognostications. Three of his sub-21 Mets from ’65, his final season as skipper, were Kranepool, Ron Swoboda and Tug McGraw, all of whom would become world champions the year Greg Goossen was a Pilot. Then again, the rest of that era’s kiddie corps didn’t necessarily have it so good — witness the long and winding road to obscurity for 1964 teen dream Jerry Hinsley — leading one to wonder how much better off the most callow mid-‘60s Mets might have been had they not been rushed onto a perennial cellar-dweller.

Greg Goossen was probably too young to be a Met when he was called to active duty, though, to be fair, he wasn’t going to be a baseball star at any age. Snider, conversely, was one of the absolute greats of his era, a period that, unfortunately for us, preceded by several years the existence of our Mets and the season he played for them.

But that’s OK, too, I suppose. In his baseball prime, Duke Snider’s job was to hit home runs and catch fly balls for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Afterwards, as best as I can tell, it was his role to have been Duke Snider.

There was something quintessentially nostalgic about the existence of Duke Snider once he quit playing. It was comforting just to hear his name, even for those of us who never saw him as a Dodger or a Met or a Giant. Whenever Duke’s name came up, particularly if it was brought up by his contemporary Ralph Kiner (or, better yet, when Duke joined Ralph for a chat when he was working as an Expos announcer in the ’70s and ’80s), it reminded you of what had been. Here was evidence that there were Brooklyn Dodgers, that there was Ebbets Field, that The Boys of Summer wasn’t just an apropos book title, that the 1950s were more than the setting for Happy Days.

Duke Snider somehow reassured me that the whole thing wasn’t just something my Brooklyn-born mother made up.

As much as I read about those Dodgers, there was a certain unreality to them in my mind, no matter how beautifully Roger Kahn brought them to life, no matter how many of their National League pennants were stitched into the permanent record. Intellectually, I got that there was a Pee Wee, a Jackie, a Campy, an Oisk and so on. I understood that the Los Angeles Dodgers were a transferred (stolen) entity. But somehow it never quite registered as real, probably because the Brooklyn I saw from the back seat of the family Chrysler on visits to relatives or doctors evoked a number of images for me, but home to a major league baseball team wasn’t one of them.

Thanks, then, to Edwin Snider, for serving as “the Duke” long after the Dodgers left Brooklyn. Thanks to Duke for showing up here and there over the decades and telling his stories, feeding our nostalgia and constituting one-third of an immortal trio not just for Terry Cashman but for the rest of us as we wrapped our heads around the way it really was. That there were Brooklyn Dodgers. That there was an Ebbets Field. That Willie, Mickey and the Duke each roamed the earth in geographic proximity to where we’d come along later. Being Duke Snider had genuine value for so many of us who are proud to call ourselves baseball fans and New Yorkers.

And being Greg Goossen? You mean to be young and a Met? Even a little too young and a Met? Who among us, no matter how allegedly mature, wouldn’t sign for that at any stage of our lives?

Two great preseason publications are out, each with contributions from Faith and Fear and other Mets writers you know and love. Get your hands on Amazin’ Avenue Annual here and Maple Street Press Mets Annual here.

by Jason Fry on 26 February 2011 3:01 pm A few weeks ago today was a new entry on my Google Calendar: 2/26 Mets WPIX 1p. A couple of days ago I saw it waiting there, suddenly not so far away. Thursday night, as plans unfolded for the weekend, I raised it as an item in the mix.

And then today, there I was coming back from brunch navigating the uncertainties of the F and A and E and C, scrambled as usual for the weekend. Through some uncharacteristic subway luck — which I took as a sign of personal virtue, as New Yorkers are wont to do — I was able to walk into my apartment, plop down on the couch and get the volume up just in time to see Jenrry Mejia throw the first pitch of 2011 — with Gary, Keith and Ron noting it as such. I was glad to see all concerned, and felt a huge smile spreading across my face.

As always with the first spring-training games, I was tremendously excited for about 20 minutes and then found my attention drifting — hence this blog post. But that’s OK — it’s as much a part of the process as dead-arm periods, waiting for the last-minute cat-for-dog trade that scrambles the roster, and, frankly, getting good and sick of spring training. (This seems to happen earlier and earlier each year.)

Where my blog partner has (blue-)blurred vision, I have double vision. I think the Mets are being constructed and run much better than they have been in years. Their offseason moves have been mostly low-risk, high-reward moves, taken amid discussions of actual statistics instead of sunnily vacuous Omarisms about Veteran Leadership and Having Been Here Before. Sandy Alderson seems disinclined to bid against himself for players or hand out ruinous options. And Alderson’s very presence seems to suggest that owners with a reputation for meddling have been convinced — at least temporarily — to change their ways.

But it’s with ownership that the double vision comes in, and I start getting a headache. I find myself in an unhappily familiar position: When it comes to the team’s finances, I don’t believe anything the Mets say.

From the minute the name “Madoff” became attached to the New York Mets, I’ve felt terrible for Fred and Jeff Wilpon. The pain of personal betrayal and the sense of violation must have been and still be agonizing. I have trouble believing the Wilpons were crooked — it seems to me like they were too trusting, and fell prey to the all-too-human impulse to let good news speak for itself rather than digging into it. (This is, granted, based on very little beyond a gut feeling at a distance.) And it must be awful to have all that get dragged into the public eye again and again.

Yet for all that, the Wilpons’ business is unavoidably my business. At my most detached I probably spend an hour a day worrying about the Mets; at full throttle, the Mets are top of mind to a worrisome degree. Not to mention the games I go to, the stuff I buy that’s slathered with Mets logos, and everything else. For obvious reasons, I’ve wanted to believe the Wilpons’ attempts to be variously reassuring, insistent and defiant in proclaiming that the Madoff mess wouldn’t impact the Mets’ operations. But believing that has gone from difficult to impossible. The team borrowed $25 million through MLB in November, a back-channel loan that club officials attempted to explain away with a curt acknowledgment and a haughty warning that “beyond that, we will not discuss the matter any further.”

I don’t believe that’s the extent of it, or that the issue won’t come back. The Mets have trained me not to.

I think the Wilpons will ultimately be forced to surrender majority ownership of the Mets — I’d call that a when, not an if. And given word of that loan, I think that “when” may be approaching more quickly than we’d thought: The Rangers were pushed onto the block pretty quickly as their own financial problems mounted, and Bud Selig’s friendship with Fred Wilpon can only go so far in comparison with his duty to have one of the National League’s highest-profile franchises on stable financial ground.

However critical I’ve been of the Wilpons over the years, I don’t welcome this: It’s cruel that the Wilpons may see Citi Field and everything else taken away without a season of glory. And those of us who want the Wilpons out should remember that there are individuals they’d probably like a lot less as owners — to say nothing of having your baseball team become a line item in a corporate earnings report.

Still, this will take a while. And that brings me back to double vision.

The Mets are retrenching this year, getting out from under a few contractual Omar Specials. It’s quite possible they’ll be doing the same next year. (I’m going to avoid talking about K-Rod’s option in an effort to not descend into sputtering rage.) And if the Mets continuing making smart deals and rebuild the farm system, this could all be fine. I’m willing to wait while the team is rebuilt according to a smart plan.

This rebuilding might even coincide with a resolution of the Madoff mess and the uncertainties around the team’s finances and ownership. In which case the Mets could be just fine, emerging from financial shadows in much better shape than when they went into them. But it feels like everything would have to break right for the timing to work out. And it’s been years since the Mets have had that kind of luck.

It’s a sunny day in Florida. The Mets have just tied the score. Everything on the field looks fine. But then it usually does. That’s the beauty of baseball. But it’s also what can blind you to the rest.

On a Happier Note: Greg and I teamed up to contribute an essay to the 2011 Amazin’ Avenue Annual about how the Mets can continue turning Citi Field from bland to grand and further embrace all things Metsian. AA is one of the finest Mets blogs in the land, and their folks assembled a Murderers Row of smart writers whose essays will help you see the Mets and baseball differently — and enjoy both even more than you do already. Besides AA’s crack staff, you can read the likes of Ted Berg, Tommy Bennett, Will Leitch and Joe Posnanski, for my money the best sportswriter on the continent right now. We’re enormously pleased to be in such, well, amazin’ company. Check out the book here — and, if you’re somehow not already a regular, Amazin’ Avenue itself.

by Greg Prince on 24 February 2011 4:37 pm Ronny Paulino reportedly isn’t in Mets camp yet. How can they tell? Based on the onslaught of images filtering north from Port St. Lucie, there seem to be approximately 2,000 players in Mets camp. Check harder — our backup catcher’s visa’s gotta be in there somewhere.

In the spirit of that which is so crowded that nobody goes there anymore, I’ve treaded (or perhaps trod) lightly on in-depth Spring Training coverage since it began to spill out of every pore of my computer, my digital device and my SNY. I’m not complaining that it’s there, mind you; it beats the hell out of staring out the window and waiting for snow to melt. But if I were perched breathlessly on every syllable regarding how good [guy I never heard of/gave the slightest thought to before this week] looked in this morning’s side session, I’d probably be OD’ing right about now.

Whereas I usually read as much of what is written about the Mets as possible, I’ve mostly skimmed the minute-by-minute Florida updates, and otherwise marveled at all the pretty pictures. My sense from my marveling is the 2011 Mets, as presently constituted, are one big blur of blue. There go a few hundred guys in Mets batting practice tops running this way and there go a few hundred more in Mets batting practice tops stretching that way. Somewhere in between, perhaps in several places at once, is the blurriest Met presence of them all, Terry Collins.

Is Terry Collins doing a great job? Well, he’s doing a job, which in itself is commendable in this economy. Otherwise it’s premature to draw conclusions based on every last pronouncement the manager makes to however many microphones are projected toward his lips. For the rest of us in our comparatively humdrum occupations, whatever Terry Collins is doing would qualify as preparation, the stuff nobody else would see, the stuff nobody else would judge us on. Terry operates on a more fascinating stage, I suppose, but everything to this point is a rough rehearsal for which the stage door happened to be left unlocked. Just because people get to watch what he’s doing doesn’t mean there’s a ton to be divined from it.

Let Collins at least manage one pretend game first…and whaddaya know? The Mets’ first pretend game is Saturday, on Channel 11, which will help me craft the vaguest of underinformed impressions regarding who should play second, who should be in the bullpen, who should be handed the ball on fourth and fifth days. Right now, I blissfully and ignorantly admit I have no idea whose those players should be. I could pick a name based on all the well-intentioned observing others have done, but I’d like to see a few pitches, a few swings, a few ground balls in exhibitions for myself. Then and only then, when I happen to be looking at the TV long enough to be impressed by a fleeting shot of [some other guy I never heard of/gave the slightest thought to before this week], will I insist that that guy has to make the team.

Right now, I only insist that there be a team, and I’m comforted that there seem to be enough Mets in St. Lucie to form forty of them. Until they sort themselves out, I’ll content myself to root for that big blue blur.

In the meantime, does MLB have a job for you!

|

|