The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 8 October 2007 9:02 pm I felt a little fear

Upon my back

I said don't look back

Just keep on walking

—KT Tunstall

So this year Fear knocked out Faith in the 162nd round. But I can't just keep on walking. Not just yet.

As was the case for Henry Bemis in The Twilight Zone after the H-Bomb proved it was capable of total destruction and before our bank teller's glasses slip off his nose, we will have time enough at last to look ahead at what needs to be done to repair the New York Mets. Goodness knows, they can use all the help they can get. But indulging my trusty rearview instincts, I'm going to devote the bulk of my blogging this week to trying to trying to make a little sense of 2007. I doubt there is great appetite to relive its final chapters, but there are a few questions about this season that continue to nag at me, so if you don't mind, I'll nag them at you.

First off, was 2007's Met denouement the Worst Collapse in Baseball History?

Does it even matter?

Once you're in the conversation, you're not really gaining anything by avoiding the No. 1 ranking. The 2007 Mets are squarely in the conversation. Whether they made a statistically louder or softer thud than all those other teams you've understood as shorthand for “collapse” all your rooting years is irrelevant. There was a collapse. What was there ain't there no longer. And anything times zero still multiplies to zero…y'know?

If there's any overarching good news on the subject of historic collapses it's that this happens to most everybody sooner or later. While we were in the midst of joining the Legion of Decline & Fall, I saw various lists of Worst Collapses pop up with the regularity of Jose Reyes. Some entries were what card collectors would call commons; some teams you see always see on these lists. Others had grown obscure. But almost every franchise's name gets called.

It's not just us.

Will 2007 Mets really become synonymous with collapse? Will it really replace 1964 Phillies in the lexicon? Will it be mentioned for all time alongside '69 Cubs and '78 Red Sox and '51 Dodgers? Or will it fade into the maw of the memory hole where the 1934 Giants and the 1987 Blue Jays and the 1983 Braves and the 1995 Angels and others who haven't been quite as mythologized reside?

As we are barely one week beyond the expiration date of the 2007 season, I'd say we don't know yet. Because it took place in New York and there is a tendency to withhold benefit of the doubt from the Mets among the brain dead media, I'd guess this will come up the next time the Mets have any kind of lead with any kind of time on the clock. Then again, I would have guessed the five losses in a row that ended our 1998 would have stood eternally as a touchstone of collapses, but that has clearly reverted to family matter.

What might work in our favor (that is, not drip-drip-drip on our heads for the remainder of our lifetimes) is that the 2007 Phillies were eliminated so quickly from the postseason. If they had enjoyed overwhelming October success, the backstory — “you know, Joe, the Phillies deserve the credit for being here, but you can't ignore the fact that the New York Mets held a seven-game lead on the Twelfth of September and…” — would have become cemented as legend. With eight teams in the playoffs and things moving as quickly as they do these days, the 2007 Mets' misfortune may prove more transient on the grand stage than we could possibly imagine right now. Right now, the Cubs, Phillies and Angels look no better than we do.

I would also contend there was no signature moment of collapse in 2007, no single signature move that backfired, no obvious failure of philosophy or strategy, so it will be tough to construct an enduring myth around what happened. Essentially, our starting pitching was almost uniformly inadequate and our bullpen was spectacularly abysmal. You could argue much more could have been accomplished, much more urgency could have been applied, somebody didn't have to slap somebody else such an emphatic high-five (that's “the Mets made the Marlins mad” storyline, which, by the by, I don't buy as an alibi as it lets failure of execution way too easily off the hook), but the air escaping from '07 can't be automatically pegged on something systemic. Willie Randolph's proclamation that the Champagne would taste sweeter once sipped through adversity may have already carved itself on his eventual managerial tombstone, but standing arms folded and motionless in a windbreaker while all about you crumbles isn't quite as sexy as Gene Mauch repeatedly starting Bunning and Short or Charlie Dressen opting to give away home-field advantage after winning the tiebreaker coin flip.

Examining the teams who qualify for the Worst Collapse conversation (as interpreted by Nate Silver at Baseball Prospectus) gives me hope on one very fundamental level: This sort of thing does not mark the end of a franchise's life. Just about everybody has one of these skeletons in the closet. There really is a next year, sometimes a very good next year. The Dodgers, shot 'round the world and through the heart as they were, won a pennant in 1952, then '53, then '55 (when they won a World Series), then '56. The '34 Giants eventually became the 1936 and '37 National League champs. The Cubs didn't win in 1970, but they remained competitive.

What do years after bode for the 2008 Mets? Only that there will be 2008 and there figure to be Mets. Hell, even the Phillies showed up for Spring Training in 1965.

Whether the 2007 Mets' collapse was worse than those proffered by other teams of the damned is something I really don't know. But now I'm wondering whether it felt worse than other horrible Met episodes. More specifically, how does 2007 deserve to be remembered? I mean after the immediate shock and disgust have worn off? (My own level of shock has subsided eight days after the fact, but my disgust lingers.)

I tend to grade on a curve. To my generally forgiving mind, there are 90+ loss disasters, then there's 1980 when the Mets flickered with hope for a few months. There are third-place finishes, then there's 1997 whose tenth-anniversary flag I've waved frequently and forcefully on Fridays this year. There are gut-wrenching near misses, there there's 1999, whose final moments Shawon Dunston and I will never forget for all the right reasons. My rule of thumb is if a year gives me something to truly treasure, I'm willing to overlook a lot of bad as water under the Whitestone.

So what was 2007? Solely one of the Worst Collapses in Baseball History? Or a year whose undeniably awful ending didn't completely wipe out what could be kindly considered its saving graces?

Was 2007 worse than the abomination of 1977? You can substitute 1993 or 2003 or 1965, if you like. The question boils down to, was losing at the end worse than losing all year? Is it better to have been in the thick of things — to have led the thick of things — even if you know you blew your part of the deal? Or would have you rather not bothered getting your hopes up so high? Would it have been just as well to have wallowed in last place since the one thing the '07 Mets have in common with various of their sad sack ancestors is they didn't see the postseason for themselves?

I'd say I never want to go through a collapse like that we just endured ever again. But I'll take my chances with spending most of the year in first place regardless of the possibility that what happened could have happened, even the certainty that what happened did happen. 2007 can't hold a hellish candle to 1977 and 1993 and the other six last-place finishes I've lived through as a Mets fan. Same for most of the too-plentiful next-to-lasters. Those were veritable 162-game collapses. I'll get my hopes up, thank you very much.

Was 2007 worse than the mediocrity of 1971? Though I don't remember a whole lot of details from 1971 as they occurred, I do remember it being a typical Mets year from my youth: It seemed we might be good, we made a little run (two out at the end of June), we had our collapse in the middle of the season (9-20 in July), someone else (the Pirates) proved much better; the hitting was lame; the pitching was good; we finished with 83 wins.

I'd sure want to have Tom Seaver any year, and '71 I've always considered his best year (20-10, 1.76 ERA, 289 K's), but years like this — and a handful of others from my youth that fit the pattern — were somehow more disappointing to me on the whole than 2007. I like knowing my team has a chance. I'd rather live most of six months with the chance things might work out than merely avoid disaster by not having much of a chance all year.

Was 2007 worse than the runner's stumble of 1987? This is a very pointed challenge. On paper, the '87 Mets contended to almost the bitter end and won more than 90 games. They were also coming off a world championship, so you'd figure there'd be some goodwill in the air. But I hated that year. I wouldn't say I hated the Mets (I rooted for 'em), but I hated the arc. I hated the inability to ever pull into first place or nose ahead of the Cardinals. I hated the bickering. I hated the Terry Pendeton home run and assorted other September calamities. For all the talk of how unlovable the '07 Mets became, I never found them out-and-out unlikable. I really didn't like the Mets as a group in '87 and they grew tough to take as individuals.

We blew 2007 to the Phillies, but at the very (very) least, we didn't give it up to the Braves. The late '80s Cardinals were the Braves cubed. It's a split hair, but losing to Charlie Manuel's Phillies didn't annoy me nearly as much as losing to Whitey Herzog's Cardinals.

Was 2007 worse than the choking precedent of 1998? The Mets had not won in other regular seasons when winning was an option, but never quite like 1998. Before “seven out with 17 to play” became a catchphrase along the lines of “I Like Ike” and “Where's The Beef?” you didn't have to think twice at this juncture in 1998 to understand the meaning of “five straight losses to end the season.” Blowing the Wild Card by effectively not showing up against Montreal and in Atlanta threatened to shadow everything that would ever happen again for the Mets. I'll never forget Jason reintroducing me to someone in September 1999 whom I hadn't seen since September 1998 with “…and you remember Greg from collapses of seasons past.” Of all that is remembered about those eventually heroic 1999 Mets, it is mostly forgotten what a fantastic job they did of diminishing the stigma attached to the '98 Mets. “Five straight losses to end the season” did not become our long-term franchise calling card. But we didn't know that in October 1998. All we knew was failure.

I had a history teacher in high school who pricked holes in the Cold War “Who lost China?” argument by insisting China was not the United States' to lose. It belonged to the Chinese. In that spirit, I would say there wasn't as much to lose in 1998. We didn't have the kind of stranglehold on a playoff spot nine years ago (one up with five to go) that we had less than four weeks ago. We could have, but we didn't. Also, it was a Wild Card. I'm rarely elitist on this, but we weren't clawing for a consolation prize in 2007. We had first place in our grasp. The '98 Mets finished 18 behind the Braves. They seemed plausible, but never probable. They were in thick of it even if they didn't lead it. When you come down to the wire twice and get tangled up in it to the point where you can't breathe twice, it's almost impossible to differentiate between the two fatal events. It's a virtual tie, but I'd have to say 2007 was ever so slightly worse given what there was to blow.

Congratulations 1998 Mets: your losing streak has finally ended.

Was 2007 worse than Called Strike Three in 2006? It was heartbreaking to lose World Series in 1973 and 2000, League Championship Series in 1988 and 1999 and absolutely devastating to not win the pennant last year. But those were postseason losses, implying postseason berths were won. Even the most painful postseason loss — and Beltran frozen by Wainwright's curve still sears the soul — is better than not playing.

2007 was worse than 2006. Definitively. It was worse than the other non-championship playoff years. It was worse than the less painful near misses of '84 and '85 and '90 in my book. It was worse in its way than a few of my esoteric favorites like '80 and '97. Maybe if you were starry-eyed in 1962 and hard-bitten in 2007, losing this lead late was worse than losing 120 to begin with. I don't want the pig to O.D. on lipstick. I don't want to come off as preternaturally Sunshine Sam. Believe me, I've been Gloomy Gus for almost every one of the past 192 hours. There was loads to not like about 2007…loads to hate it for, too, I suppose.

All I'm saying is not only could have this entire Met season been worse, entire Met seasons have been worse. As slogans go, it's not as rousing as “Your Season Has Come,” but it's probably more truthful.

by Greg Prince on 7 October 2007 9:29 pm In the interest of Eastern Division solidarity, it's high time we rouse ourselves from our stupor and extend our heartiest congratulations to the Philadelphia Phillies and wish them all the luck in the world as they pursue a world championship. Go get 'em in the NLDS, guys!

Wait a sec…I'm just being handed a bulletin…I see…really?…three straight?…you sure?…no, it's fine…it's more than fine…this is AWESOME!

Um, just to clarify the above remarks, we extend our heartiest congratulations to the Colorado Rockies and wish them all the luck in the world as they pursue a world championship. Go get 'em in the NLCS, guys!

All right, so I haven't had my head that far down in the sand not to have noticed the Rockies made quick work of our nemeses this week. And I'm not so numb that I didn't enjoy the three blinks of an eye it took to complete the division series round in the National League — and not just because it means fewer Frank TV ads. I wouldn't have completely minded the Cubs getting the monkey house off their backs already yet after 99 years, but I can never quite bring myself to root for them even in benign circumstances (probably because they as a people are still sniveling over 1969), so nice job, Diamondbacks. The Rockies' conquest of the Phillies, however, required no sorting of the mixed emotions.

The Phillies are dead! Grab a seat next to us, fellas.

You can't be a Mets fan and not have been drawn to the one intimately familiar presence in those neat-o Martian jerseys the Colorados wear. I've actually read a little grumbling here and there that of all the Rockies to blow the P straight off those red caps, why did it have to be our former shortstop and second baseman Kaz Matsui who led the charge? We liked that somebody was batting .417 and driving in six runs versus Philadelphia…but did it have to be Kaz?

Damn right it had to be Kaz! I for one couldn't be happier that it was our wayward leadoff batter, the world's most misunderstood international superstar during his 2-1/2 years in New York.

Don't take this as revisionist history. I was relieved (relieved more than glad) when Omar Minaya sent him to Denver for Eli Marrero. It was just time to say goodbye to a bad fit and give a player who was given some poor guidance to start over. Kaz's contract was up after '06 and I thought he'd hightail it back to Japan, deciding the grass and dirt infields of America just weren't his kind of playing fields.

But he stayed and he became part of the feelgoodiest story in baseball in 2007. It's not like he put up Rickey Henderson numbers in the leadoff spot for the Rockies, yet he seemed to have truly found himself two-thirds of a continent away. He wasn't Kaz Matsui global savior at Coors Field. He was just Kaz Matsui, baseball player. On a team that never marketed the spit out of him, that was plenty. When he began slicing and dicing the Phillies' pitching staff, it brought a Mr. Met-size smile to my face. True, any Rockie doing that would have generated such grinsome behavior, but it was just nice to see it from Kaz.

There shouldn't be any “well, the Mets let another one get away” misgivings to mull here. We saw it wasn't going to happen here. We saw he wasn't comfortable in Queens. We saw that all his effort was mostly for naught despite flashes between 2004 and 2006 of the kind of offense he delivered in Game Two at Citizens Bank Park. So we shouldn't rue Marrero-for-Matsui nor spite a speck of his success in Colorado.

But we ought to ask ourselves a question: what's wrong with us anyway? As quickly as I would categorize Kaz Matsui among the almost indisputable “he needed a change of scenery” types who have left Shea to blossom elsewhere, I have to wonder why there are so many of those types and if we have a disproportionate share.

Kaz Matsui had to leave the Mets to blossom.

Jason Isringhausen had to leave the Mets to blossom.

Jeff Kent had to leave the Mets to blossom.

Kevin Mitchell had to leave the Mets to blossom.

Mike Scott had to leave the Mets to blossom.

Nolan Ryan had to leave the Mets to blossom.

With everybody leaving and blossoming, how does our garden grow?

Kaz was treated shabbily by the vocal contingent in the stands, no doubt. Kent didn't exactly win over the fans who weren't in the mood to be won over by a drugstore cowboy. But the other fellows in question weren't targets for the boobirds. Maybe country boy Ryan just needed to get regular work. Maybe Scott needed to learn to scuff the ball. Maybe Mitchell wouldn't have been held above suspicion long enough to get the at-bats to become an MVP. Maybe Izzy needed to get his head together and embrace a new role. Maybe none of them were “New York guys”.

But what does it say of New York? What does it say of the Mets and Mets fans? I suppose we've gotten a few in return, guys who came here and were uniquely suited to New York after finding only failure elsewhere, but it's hard to think of too many players who meet the equivalent test. Who was run or driven out of another town only to come here and explode like Matsui has of late or the others did in the course of their careers?

The Hernandezes and Carters and Piazzas weren't in this mode. They were already superstars when they came to New York. And I'm not thinking of an unknown kid like Jerry Grote or a surprising pickup like Rico Brogna or a disregarded journeyman like Rick Reed or a discarded veteran like John Olerud. I'm thinking of somebody else's washout, somebody else's pariah, somebody else's outcast.

I'm still thinking.

by Greg Prince on 6 October 2007 11:49 pm The hunter is now the hunted.

Your University of South Florida Bulls, perhaps dizzy from their unprecedented, unpredicted, unreal! ranking in the AP writers’ poll as the No. 6 team in the nation, were severely challenged by a team that used to be them, the Florida Atlantic University Owls. But the Bulls withstood the challenge and the almost inevitable letdown (Owls? Who? Who?), prevailing 35-23 at Fort Lauderdale and raising their record to 5-0.

When I attended USF, there was a rule that you had to fulfill nine credits during a summer semester. FAU wasn’t far from the condo my parents owned in Hallandale. There was some talk I should try to do my summer on their campus, in Boca Raton, to save on dorm expenses. But I didn’t.

And honestly, that’s all I know about Florida Atlantic. That and the revered former coach of the University of Miami Howard Schnellenberger is their coach. But I just found that out.

USF rose from No. 18 to No. 6 last week by defeating powerhouse West Virginia on the same night another Florida team was annoying me in Queens. The Bulls have been a most welcome Band-Aid on my deep, deep, deep baseball-related wound this week. USF being ranked No. 6 is like the Savannah Sand Gnats winning the NLCS.

Over the Mets, probably. If the Mets in fact were to qualify. Which we all know couldn’t happen this year.

That’s the thing, damn it. I can’t truly enjoy anything anymore. I can’t enjoy believing that something won’t go wrong. I can’t enjoy looking forward to success for another team in another sport. I’m not even really enjoying the Cubs and Phillies and Yankees flailing away in their respective endeavors because I now understand like I never understood before that it could all end without warning…or warning less urgent than playing .500 ball for four months.

But the Bulls don’t know that. In Tampa, it’s the spiritual equivalent of 1997 (the year our football program began, ironically for me if no one else). I’m suddenly reading articles about USF in the New York papers. In Florida, they’re full of talk about how the Bulls may be the best team in the state. Better than the gosh darn Gators for crying out loud! I’m hearing about how students for the first time ever are lining up for tickets, how the Bulls are selling out home and road games.

This is amazin’, amazin’, amazin’…and I’m holding my breath wondering how badly it’s gonna end.

Today SNY was showing the Beltran/Delgado vs. Pujols home run derby from August of ’06. That’s a great game, yet all I could think while looking in on it was “you poor people sitting there. You don’t know that the Mets aren’t going to win the World Series in 2006, aren’t going to make the World Series. And when, come October 2006, you say ‘wait ’til next year!’…you won’t wanna know.”

Bulls are 5-0 and though I know the score was a little closer than it should have been, they should remain highly ranked (hell, No. 5 Wisconsin lost, so maybe they’ll move up). I should just enjoy the moment, I guess, and not worry about where it might all lead.

Remind me to remember that come spring, would you?

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2007 8:18 pm

If you can’t make it out, those are — clockwise from the top left — Rey Ordoñez, John Olerud, Todd Hundley and Bobby Jones at play on my torso. We were in Cooperstown on August 26, 1997. The Mets were 70-60 at that moment, trailing the Florida Marlins by 5-1/2 games in the Wild Card race. And as I’ve been telling you once a month since April, I couldn’t have been a whole lot happier.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2007 7:47 pm When the season began, they were nobody. When it ended, they were somebody. If it’s the first Friday of the month, then we’re remembering them in this special 1997 edition of Flashback Friday at Faith and Fear in Flushing.

Ten years, seven Fridays. This is the last of them.

Here’s the crux of it. This is why I remember 1997 so deeply and so fondly and why it resonates so much for me for so long after the fact.

It made me cry.

I’m not being cute about this at all. I’m not going to give you the ol’ “I think there’s something in my eye” bit in telling you what 1997 did for and to me. I’m not going to deny a bit of it. Why deny? I couldn’t be prouder that I violated the Jimmy Dugan edict that there’s no crying in baseball. I like to think I’m the biggest Mets fan you’ll ever meet. I think I proved it to myself on Sunday afternoon, September 28, 1997.

That was the last game of an 88-74 season. I just went to the last game of another 88-74 season. If it made me cry, it was from a culmination of angst and exhaustion and for maybe two seconds while washing my hands in the men’s room after it was over. 2007 provided the kind of ending that made you want to wash your hands of the whole thing right away.

The last day of 1997 wasn’t like that. The last day of 1997 was something beautiful. It was the end of something beautiful.

I’ll never have another season like that. I’ll never again be capable of being surprised like that, of being delightfully surprised like that, of waking up rooting muscles that I assumed had gone permanently dormant. I’ll never again care the care of the innocent, unburdened by cumbersome backstory. Even with 28 previous seasons of Mets fandom in the books, 1997 wiped the slate clean. Past failures were ancient history. Past successes served as useful precedent.

I’ll never be able to enter a season expecting nothing and end it having been given oodles and oodles of something. Another Mets team can come along and do better than expected and it will be gratifying, I’m sure, but it will never sneak up from behind and embrace me like this one did. Once it’s happened once, you can’t be surprised if it happens again.

I’ll never again find myself surprised that I’m so immersed in a particular team or a particular season. I’ll never again be surprised that I find myself believing we can overcome a suffocating opponent or an imposing margin. I’ll never again feel shock that my team that wasn’t supposed to be any good proved to be not bad at all. I’ll never again be stunned by a team winning a little more than it loses even if it had just spent years losing far more than it had won. I’ll probably never again find deep and enduring satisfaction in a season that comes up just a few games short.

But short of what? Maybe you’re wondering how an 88-74 season can be so damn meaningful when you’ve just seen how awful the most recent one was. Context is everything, of course. Coming off a division title and building a record of 83-62 and a lead of 7 games, you’re not going to think much of 88-74.

But after 71-91 and after 69-75 and after 55-58 and after 59-103 and after 72-90 and after 77-84 and after feeling you were eternally consigned to circling a tunnel of irrelevant submediocrity, U-turning from one lousy year into another into another into another…you, the biggest Mets fan you insist anybody will ever meet…you’d think a lot of that.

Especially if it came with possibility. As painstakingly detailed across the previous six Fridays devoted to this topic, it wasn’t just the first winning record since 1990 that sent me over the Met moon in 1997. It was the unforeseen chance that there might be tangible reward. A playoff spot was in reach for the first time since 1990, too. The Mets finished within four games of the Wild Card that year. They competed ferociously for it into August, fell off the hunt a bit as September neared but clung to the legitimate possibility that they, the downtrodden Mets, the laughable Mets, the heirs to futility Mets, the next-of-kin to Anthony Young Mets, the artists formerly known as the fourth-place, 91-loss Mets — that they would make the playoffs. That if they made the playoffs, they could win a division series, a league championship series, a World Series even.

They didn’t, but that’s hardly the point of 1997. They made me believe they could. They made me dream they could. When the dream was dashed for the simple reason that they weren’t quite good enough, it bothered me as little as that sort of thing could bother me. Imagine investing all your fanhood in the hope that your team, on the verge of breaking through all season, actually breaks through. Then it doesn’t. Would you be disappointed?

Weren’t you just recently disappointed?

My 1997 was no more than tinged by disappointment. Not colored by it, certainly not defined by it. Even as I had grown to expect winning baseball from my team across May and June and July, when it didn’t automatically come in August and September, it didn’t kill me. Not because I didn’t expect better, but because I was given the gift of expectation at all. When the season was over, I looked around the sport. Twenty teams missed the playoffs. A few of the other nineteen franchises had probably exceeded their fans’ expectations, but I couldn’t imagine they didn’t feel let down somehow. Of the eight teams in the postseason, seven sets of fans were bound to be crushed by coming so close and falling just shy. The Giants and Braves each lost to the Marlins; that wasn’t supposed to happen. The Yankees and Orioles lost to the Indians; that wasn’t supposed to happen. The Indians watched a Game Seven lead slip away in the ninth inning and with it their first world championship in 49 years; that’s never supposed to happen. The fans of the eventual world champions, the Florida Marlins, got to celebrate heartily for a couple of days before their owner almost immediately ripped their roster apart. That’s totally unheard of.

By Thanksgiving 1997, everybody else who rooted for a baseball team was experiencing some degree of misery. And I was still thrilled and thankful. I’d had a year I couldn’t anticipate and now I couldn’t forget about it, not then, not now.

That’s why I cried on the last day of the season ten years ago. That’s why I was at the last day of the season ten years ago. There was no way I was missing it. I was invited to a wedding on Sunday, September 28, 1997 by a co-worker and fellow Mets fan. I didn’t ask him what the hell he was doing scheduling a wedding on the last day of the season, but I was clear on why I was RSVPing no.

I have a previous engagement, I said. I have another affair to attend.

I went to Shea Stadium alone that Sunday. Couldn’t have possibly gone with anybody else. It had to be me and my team, just us two, even if I was only going to be making the sound of one fan clapping. Technically, we weren’t alone. Paid attendance was announced as 27,176, pretty good for those days. It may even have been fairly accurate. There were apparently others who recognized 1997 for what it was. But I didn’t need to talk to them.

Having been to a very memorable Closing Day in 1985 when the last Mets team to come achingly (if unsurprisingly) close said goodbye by gathering en masse in front of their dugout and tossing their caps in the stands, I decided I wanted to sit in good seats. Maybe I’d catch a cap. Maybe I’d be in the middle of the fuss. Before I had a chance to seek out someone looking to unload the last of his season boxes, someone approached me. A man in his 50s, not very tall, offered me a $25 Metropolitan Club seat for $15. If they weren’t right behind the Mets dugout, they were darn close. I said yes.

Not having dealt that much with either scalpers or non-licensed ticket agents, I wasn’t expecting to sit next to this fellow once inside. But he became my neighbor. When I thanked him for the view, he told me not to thank him, but thank his brother-in-law. They were his company’s seats. Oh, I said, my thanks to him. He couldn’t make it today, huh?

“No, he died the February before last.”

It also turned out this same guy, the one who was living, had some kind of Tourette tic wherein he’d have to repeat every name the public address announcer broadcast (PA: “Now batting: Keith Lockhart”; Strange dude: “Keith Lockhart”). He also brought a glove and held it high in the air with every foul ball that was popped up, no matter where it was heading. And he referred to Astros manager Larry Dierker as Bobby Dierker.

Like I said, I didn’t need to talk to anybody that day.

The Mets were playing the Braves, the Braves who had won their third consecutive Eastern Division crown, the Braves who were forever tuning up for the postseason. The only Met with anything specific to play for was John Olerud, making a sudden rush on 100 runs batted in. He’d been driving them in relentlessly of late. He entered the week with 88 and entered the day with 98. Oly did his part with Olylike precision, doubling home Alfonzo in the fourth and blasting a three-run homer in the fifth. He got to 102 before Bobby Valentine pulled him.

The Mets A/V squad did their part, too. Eschewing the usual promotional rubbish, every half-inning DiamondVision break focused on some aspect of what made 1997 so enjoyable, with several of the vignettes devoted to the team’s Amazin’ Comebacks. There was Oly in May beating the Rockies, Baerga taking it to the Braves in June, Everett and Gilkey executing the most Amazin’ Comeback of them all (down 0-6 in the ninth, winning 9-6 in the eleventh) against the Expos two weeks before. Those of us among the 27,176 who were Closing Day pilgrims applauded each clip heartily. One gentleman sitting in front of me, however, scoffed.

“This is a results-oriented business,” he informed me, “so all this is meaningless.” He went on to downgrade these Mets, scoffing in particular at the acquisition of “Hal McRae.”

Brian McRae, I said. The Mets got Brian McRae, the son of Hal McRae.

He shrugged. “I stopped following the Mets when Frank Cashen traded Kevin Mitchell.”

“So,” I asked, “why are you here?”

He pointed to his son. The kid dragged him to the game. Fortunately, the kid lost interest around the time Olerud was reaching the century mark and Dr. Buzzkill exited the premises. Yet another good thing about this season. His departure meant an empty nearby seat that allowed me the chance to slip away from the glove-and-repeat guy.

It wouldn’t have really mattered had the Mets not won this game, but that wasn’t the sort of thing the 1997 Mets wouldn’t do. Of course they won. The Braves may have been checking travel itineraries, but the Mets were playing exactly as Bobby V had had them playing all year, living up to his mantra that the most important game of the season was the one they were playing next. Olerud’s homer had made it 5-2. Alberto Castillo and Rey Ordoñez tacked on a run apiece in the sixth. And Matt Franco launched one over the right field wall to lead off the eighth. That made it 8-2 Mets. That would be the final.

The excitement was building among the truly faithful. PA announcer Del DeMontreaux had urged us all afternoon to stick around after the final out for the end-of-year video tribute to the season. When the Mets had something to salute, they usually did it very well. In 1985, they set their highlights to Sinatra’s “Here’s To The Winners”. In ’88, they used “Back In The High Life” by Steve Winwood. I couldn’t wait.

I really couldn’t. After Greg McMichael retired Rafael Belliard for the first out of the ninth, I stood up in front of my Metropolitan Club seat and started clapping. I wasn’t alone. The anticipation for a final out that wasn’t going to clinch anything was overwhelming. When Greg Colbrunn flied out to Carlos Mendoza in left, the applause and the shouting rose. Everybody was now standing. You wouldn’t have known there was no postseason for us. You wouldn’t have known this wasn’t the postseason. I had my Walkman on and heard Gary Cohen describe the scene with surprise. Yes, he said, I guess it had been a good year. These fans are certainly enjoying the last of it.

McMichael worked the count 0-2 to Andruw Jones. Then he struck him out swinging. The Mets won. The season was over.

The roar was incredible. The Mets burst out of their dugout, not to celebrate beating the Braves, just to celebrate, at the very end of what they had accomplished, themselves.

They stood as we stood. They watched as we watched. The DiamondVision blinked on and we heard Gloria Estefan:

If I could reach

Higher

Just for one moment

Touch the sky

From that one moment

In my life

There the 1997 Mets were again. Keeping me up late from California. Winning the first battle of New York. Keeping pace as long as they could with a dream that came from I don’t know where. There were walkoff hits and clutch strikeouts and sensational grabs in the hole. There the Mets were, up on that screen, doing everything that made me stand up when there was one out in the ninth and made me start applauding — and crying — before the game was put in the books.

Yes, I was in full lachry-mode. There was a rain delay behind my glasses and no tarp capable of keeping the field dry. I could not stop bawling. And I made no attempt to stop. Neither did at least three other people standing in my midst. There were two fans who held each other tight like it was New Year’s Eve during wartime. I wasn’t the only one who had come to Shea today for this. I didn’t come to this game alone after all.

The video ended. The crowd cheered. I kept crying. I never did that for baseball before. Then I did something else I had never done. I climbed on my seat and began chanting LET’S GO METS! LET’S GO METS! Others followed. Maybe they would have done so without my lead.

The players waved, Todd Hundley among them. Hundley had left the team for elbow surgery a few days earlier. He emerged from the dugout in street clothes. Of course he was coming back for the final day, he told a reporter after the game — he wasn’t going to miss the video for anything. Carlos Baerga was out there, too. Baerga was booed fairly frequently since becoming a Met, since becoming the latest in a long line of Mets who didn’t live up to their previous billing. When I eventually saw highlights of the lovefest on TV, I saw Carlos Baerga standing on the field wiping a tear from his eyes.

I was still crying as it ended. The players threw their caps to the fans immediately behind their dugout, and I was still crying — and not because I was too far back to get a cap. We were thanked for coming, and I was still crying — and not because there was no game tomorrow. All attempts to compose myself failed. I left Shea crying, I boarded the 7 train crying, I waited at Woodside crying, I cried the whole way home until I finally forced myself to cut it out as the LIRR pulled into East Rockaway. I walked from the station to our house, came up the steps of our apartment, and as I began to describe for Stephanie what the day had been like, I started crying all over again.

Next Friday: The Champagne of centerfielders.

by Greg Prince on 5 October 2007 8:47 am I’m still working on Flashback Friday as regards the final game of the season ten years ago, but I thought it would be interesting in the interim to provide some emotion-free context for 1997.

Twenty-four men became New York Mets for the first time in 1997. Four of them — John Olerud, Rick Reed, Todd Pratt and Turk Wendell — would become mainstays of the Mets club that broke the franchise playoff drought in 1999. A few of them — the balk-magnet Steve Bieser, the first Met Japanese pitcher Takashi Kashiwada, human gas can Mel Rojas — gained a degree of triviality or infamy during their short stays. One — Cory Lidle — is no longer with us.

Most simply came and went. It would take a hardcore collector of data or baseball cards to recall with much depth the Met tenures of Yorkis Perez or Gary Thurman or Carlos Mendoza or Barry Manuel or Shawn Gilbert or one-game wonder (one inning at third) Kevin Morgan. Half of the 24 new Mets of 1997 never played with the Mets again.

Forty-five men in all were Mets in 1997, 21 of whom had previous Met experience. Five of those holdovers — John Franco, Edgardo Alfonzo, Bobby Jones, Matt Franco and Rey Ordoñez — would see postseason action with the club in ’99 and/or 2000. Nine of them, including the traded Lance Johnson and the caustic Carl Everett, would not be Mets beyond ’97. John Franco, who predated all his 1997 teammates in Queens, remained a Met the longest, through 2004. While Alfonzo and Everett were Long Island Ducks this past summer, Jason Isringhausen is the only player from that ’97 team to finish 2007 on a big league roster.

Roberto Petagine was the only Doubleday Award Winner to be recalled to the majors in September. The only future Mets to be recognized as top minor leaguers in the farm system that season were Grant Roberts (Capital City) and Endy Chavez (Gulf Coast). The top pick in the amateur draft that June was lefty pitcher Geoff Goetz. The most notable selection to eventually play for the Mets was Jason Phillips, chosen in the 24th round.

Snow white uniforms were introduced as “Sunday-only” togs, but eventually supplanted the pinstripes as the de facto primary uniform of the sartorially confused Mets over the next decade (black was added to the wardrobe in ’98). The white “ice cream” caps with blue bills intended to accompany them faded quickly, however, disappearing from player’s heads by June. Uniform number 42 went up on the left field wall April 15, as Jackie Robinson’s entry into the major leagues was honored first and foremost at Shea Stadium by the pioneer’s widow, the commissioner of baseball and the president of the United States. Every team, including the Mets, wore a right-sleeve patch commemorating the 50th anniversary of Robinson’s breaking the sport’s color line.

On the promotional front, 1997 introduced us to International Week, postgame Merengue concerts, Kids Opening Day and a one-off sunglasses giveaway sponsored by American Sports Classics, a Cablevision-planned rival to Classic Sports Network (now ESPN Classic) that never got off the ground. Fans of legal drinking age were presented on August 10 with a narrow “cooler bag” designed to accommodate several cans of beer; it looked more like a belt than a bag.

Interleague play provided the most substantial alteration for 1997. Of course National vs. American meant the first Subway Series and the attendant legend of Dave Mlicki, who shut out the Yankees 6-0 in the first crosstown meeting at Yankee Stadium on June 16. Overall, the Mets compiled a 7-8 record versus the American League East, which then included Detroit, where the Mets visited Tiger Stadium for the first and only time. Their initial Interleague game was against the Red Sox at Shea. The Mets’ competition for the Wild Card, the Marlins, went 12-3 against A.L. Teams, meaning the Mets actually owned a better record in intraleague play than the team that beat them out of a playoff spot.

Mets games were cablecast on SportsChannel for the final time in 1997; the outlet’s name would change to Fox Sports New York a year later. It was also the final season Coca-Cola would be poured at Shea Stadium and the final year before the addition of Milwaukee and Arizona to what had been the fourteen-team N.L. The Mets would lose Lidle (Diamondbacks) and Mendoza (Devil Rays) in the November expansion draft.

In Bobby Valentine’s first full season as manager — Steve Phillips succeeded Joe McIlvaine as GM on July 16 — 1997’s record represented an improvement of 17 games over 1996, the third-best one-year improvement in Mets history, following only those generated in 1969 (27 games) and 1984 (22 games). Bobby Jones and Todd Hundley represented the Mets as All-Stars, though Hundley was injured and did not make the trip to Jacobs Field. Hundley, who graced the 1997 yearbook cover in a holographic rendering of his record-setting home run from the September before (most by a catcher), led the team in homers again with 30. Butch Huskey was second with 24. The other catcher named Todd, Pratt, homered in his first Met at-bat, off the Marlins’ Al Leiter in early July. Olerud cracked the 100-RBI mark on the final day of the year, finishing with 102. He also hit for the cycle on September 11. Alfonzo, graduating from utilityman to everyday third baseman (no Met had played the position more in one season since Hubie Brooks in 1983) was the team’s leading hitter at .315, good for eighth overall in the senior circuit; he was also the only Met to gain MVP votes, finishing 13th in the balloting. Ordoñez’s acrobatics earned him his first Gold Glove at short.

Jones, who struck out the two most prominent sluggers of the year (Mark McGwire and Ken Griffey) in the All-Star Game, led the pitching staff with 15 wins, while Reed, enjoying one of the great surprise seasons in Mets history, pitched to the lowest ERA on the team at 2.89 — sixth best in the National League. Reed, Mark Clark and Armando Reynoso each homered, making it the only season in which three different Met pitchers went deep. John Franco saved 36 games, fourth-most in the N.L. Greg McMichael was the workhorse with 73 appearances. Pete Harnisch started Opening Day in San Diego, though did not finish the year as a Met, sharing that unusual footnote with Mike Torrez (1984).

The season opener at Jack Murphy Stadium was the Mets’ first in California since 1968. After nine mostly ragged games out west, the Mets took the unusual step of slating their Home Opener for a Saturday in deference to the Yankees raising their first World Series flag in 18 years one day earlier, but rain pushed the Mets into opening up with a downbeat Sunday doubleheader attended by fewer than 22,000 fans, the lowest total since 1981. The season’s attendance of almost 1.77 million was the Mets’ best in four years and the last time, presumably, that the Mets would fail to draw 2 million to Shea. One scheduling quirk unique to 1997 was the playing of 17 separate two-game series (squeezed in to accommodate Interleague and disliked by all concerned) and five “wraparound” Friday-Monday four-game sets. It was all laid out in pocket schedules whose covers were graced by Gilkey or, later, Hundley.

No team in the majors came from behind more often to win than the Mets, who did it 47 times. Ten of the Mets’ victories were of the walkoff variety, including three on home runs (Olerud, Everett and Bernard Gilkey). The come-from-behind vibe echoed the Mets’ performance in general, as their 80-60 record from April 27 to the end of the season was second only to the Braves in all of the National League over that five-month span. The final 140 games erased the season’s unpleasant 8-14 start, even if it wasn’t quite enough to lift the Mets past Florida and into their first Wild Card.

by Greg Prince on 4 October 2007 4:06 pm I may have accidentally made sense eight months ago:

Don't know if it's still conventional wisdom in baseball circles to define a player's prime as more or less the ages of 28-32. Since conventional wisdom never dies, probably. But if that's the prime — when you're old enough to know better and young enough to successfully implement what you know — we lack prime time on our team…

Other than Carlos Beltran Superstar, 30 as of April 24, nobody among frontline Mets is in his prime by traditional standards. But when were these traditional standards set? Probably when average life expectancy, to say nothing of typical career endurance, was a whole lot lighter. Yet this mildly freakish two young/one prime/three kinda old/one rather old/one practically my age demography has been nagging at me a bit as the wind chill turns these venerable bones cranky.

Selective cutting and pasting omits my February rationalization that everything was going to be fine, that the young Reyes and Wright along with the old Lo Duca, Delgado, Valentin, Alou and Green would mesh wonderfully with Beltran and we'd all be figuratively making love to Betty Grable on the White House lawn by Christmas.

To be honest, I'd forgotten this momentary age-related anxiety until after the season was prematurely over and I looked around and thought, man, almost everybody on this team was either too old or too young. Or, more accurately, too injury-prone or too immature. Most of those added on both ends of the age spectrum throughout the campaign fell into those categories as well.

Obviously vintage isn't everything. David Wright is extraordinarily developmentally advanced (except maybe in the field) while Moises Alou apparently stole the soul of a much younger man in September. Nobody was checking birth certificates in Philadelphia, but now that I'm looking at their roster, they sure do have an everyday nucleus that seems a little more geared to peaking. Just about every key player was between 26 and 31 this year.

As I've heard myself say to myself many times since Sunday, I don't know, I just don't know. But maybe it was more of a warning sign than could have been appreciated last winter when merely being the Mets seemed license to print playoff tickets well in advance of Opening Day.

by Greg Prince on 3 October 2007 7:11 pm TBS' postgame show will be presented by Captain Morgan Rum. What a coincidence. So is my week.

As the Phillies and Rockies prepared to kick off (take Colorado +3), I found one thing to take solace in. And it's a reach, but what the hell — it's not like I'm reaching into my pocket for Game One tickets.

At the All-Star Break, which is one of those junctures you're supposed to look at for who's leading and where they'll wind up, the four National League representatives to the 2007 postseason were set to be the Mets, the Brewers, the Padres and the Dodgers. I'm sure there were Power Rankings backing up that likelihood. For that matter, the Tigers looked like a lock in the A.L.

The teams that usurped the places of those teams were only marginally on the radar. The Diamondbacks were 3-1/2 out in the West. The Cubs were 4-1/2 out in the Central, one game over .500. The Phillies were the same length back in the East and at .500, behind us and the Braves. The Rockies were four from the Wild Card and also at .500. And in the American League, the Yankees were .500 and eight out of the Wild Card.

No, this does not make anybody feel better but there is a nugget of evidence that we are not alone in being on the outside looking in this week after thinking otherwise.

Maybe we can round up the not-quites and set up a tournament.

Getting more rest, at least. I drifted off while watching Baseball Tonight after midnight, but stirred long enough to see they were counting down the ten biggest moments of the year. Too groggy to follow the numerical narrative, I saw Matt Holliday sort of crossing home plate and figured it was No. 1. Next thing I heard was “greatest collapse in September baseball history” and thought, no, don't tell me…turns out we were only the No. 2 story of the year.

Never thought I'd say this, but thank heavens for Barry Bonds.

So, did watching the Cardinals accept their World Series rings inspire the Mets or what?

Finally, happy 56th anniversary to the Shot Heard 'Round the World. Next time ownership decides to model our team on one of its predecessors, can we look a little to the one that didn't blow a 13-1/2 game lead for inspiration?

by Jason Fry on 3 October 2007 1:03 am

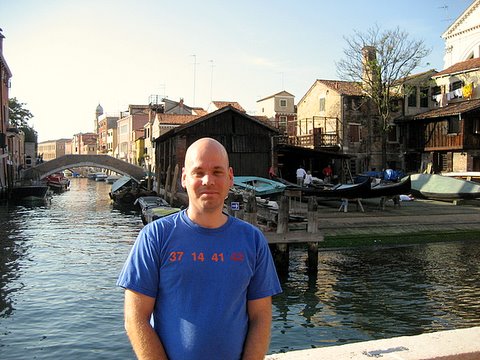

| Last month as the Mets were struggling to stay above water, Jace went to a city that could say the same, as chronicled here. For more about my adventures and misadventures trying to follow the Mets from overseas, see yesterday’s Real Time column from the Online Journal.If you’ve never been and get the chance, go to Venice. It is so worth it, even during a pennant race.We hope to have more Faith and Fear shirts soon — in the meantime, if you’ve got a snapshot of yourself bringing the colors to a new part of the world, send it to us and we’d be honored to put it up. |

|

|

by Jason Fry on 2 October 2007 2:30 pm

Charlie Hangley on the left, Jason on the right. Snapped a month ago, perhaps an hour after Pedro completed his triumphant comeback, on a sunny afternoon on Long Beach Island. Would have been posted earlier, but ran afoul of the magic-number countdown. About which the less said the better. Don’t worry, Charlie and Jace. Summer will return, LBI will still be there and we’ll all feel differently about the Mets. It’s a promise.

|

|