1. The Mets ran this ticket special in the 1980s that was incredibly successful. For the price of one admission, you could see the most fearsome competitor in the game, a peerless clutch hitter and first base play that was as revolutionary as it was nonpareil. They were also willing into throw in for that one ticket a consistent .300 hitter, a guy who ran the game like a point guard and a window into the mind of the most intelligent ballplayer you’d ever see or hear. Oh, and if that wasn’t enough to lure you in, you’d watch somebody who was looked up to by almost all his teammates, experience the hit that turned around Game Seven of the World Series and, if you requested it, the second-hand effects from a stream of Marlboros. Actually, you got the cigarettes whether you wanted them or not. Still and all, a really great deal. The Mets sold a lot of baseball with that package, especially in ’86. It was an incredible deal. So was the one they made in ’83 that made it possible.

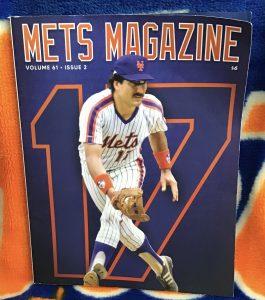

2. The above paragraph was written, by me, in 2005. I believe it still holds up as testament to the abilities and impact of Keith Hernandez, first baseman for the New York Mets from 1983 to 1989. I wrote it an appropriate 17 years ago to introduce the new blog Faith and Fear in Flushing’s recall of Mets history, and who could recall Mets history without wishing to dwell on the presence of No. 17, Keith Hernandez?

3. No. 17 becomes officially retired this Saturday, July 9, 2022, one day after an aggravating Mets loss to the Marlins and 32 years since the man who wore it last played major league baseball. It’s fair to rhetorically ask, “What took so long?” though at this point the answer is irrelevant (we’ll say it was the Wilpons). Once a number or a plaque goes up, it’s tough to summon dissatisfaction with the flaws in the process that kept the ceremonies from happening all those years.

4. Yet 32 years is a very long time to have waited to bestow an honor on a figure so essential to this franchise’s identity. Then again, the Pittsburgh Pirates waited 32 years from Ralph Kiner’s final game — like Keith, Ralph finished up with Cleveland — until they decided No. 4 should be retired. From the vantage point of someone who’d spent a lifetime learning baseball from Ralph Kiner (and learning what Ralph Kiner did to a baseball in Pittsburgh), that seemed absurdly long, too.

5. Ralph and Keith, besides both theoretically filling out a blank Wordle row, proper noun prohibition notwithstanding, strike me as riding similar trajectories after their distinguished playing careers concluded. Their fame grew in so-called retirement, certainly in New York. The Pirates may not have been directly nudged into action by their erstwhile slugger and matinee idol having become a broadcasting institution for their rivals to the east, but by 1987, they could no longer dismiss all he’d meant to their history. His 4 was too big to ignore at the confluence of the Allegheny and the Monongahela. Ralph said it didn’t bother him that the club that traded him to the Cubs in 1953 waited 34 years to properly honor him, but others where the mighty Ohio River took shape saw it differently. “We’re talking here about one of the greatest players ever to put on a Pirate uniform,” his old roommate Frank Gustine vouched in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as the Kinercentric ceremonies approached. “Why it took so long I really don’t know.”

6. Why it suddenly happened for No. 17 in 2022 when every opportunity existed through the 1990s, the 2000s and the 2010s perhaps speaks to the presence of a new team owner in Flushing (come to think of it, the Pirates were under fresh management in 1987). Maybe once the Mets got Mike Piazza’s 31 and Jerry Koosman’s 36 squared away, the prevailing vibe was “who’s next?” Keith’s been next for a while. The Mets were last when Keith showed up. They were first soon enough.

7. Keith Hernandez ranks 13th among all Mets in base hits, 12th in runs scored, 12th in doubles, 10th in his beloved ribeye steaks, 15th in extra-base hits, 12th in total bases, 10th in times on base, 40th in home runs, 6th in walks, 4th in on-base percentage, 26th in slugging percentage and 15th in OPS. Only in batting average, something for which he won a crown in St. Louis, does Keith rank in the career Top Three of a discernible category for the franchise, with his .297 average third, a long way shy of John Olerud (.315) and currently five points behind a surging Jeff McNeil. Keith Hernandez doesn’t rank first in any given offensive grouping that Baseball-Reference bothers to track.

8. Yet if you needed a Met up to continue a rally, to bring a runner home, to tie the score, to win a game, who is the very first Met you’d want up at bat?

9. Defensively, I don’t have a number handy to explain No. 17. I don’t need a number to explain No. 17 in the field. If you didn’t live through the Gold Glove defense, you’ve seen the highlights. As with the hitting, the truth lives up to the legend. From the annals of real-time jaws dropping in disbelief, however, I think it useful to share a few quotes from a June afternoon in 1984 when Keith Hernandez’s positional expertise — first displayed in snagging a Tim Raines liner that appeared destined for extra bases, then by rescuing a double play relay that Jose Oquendo bounced in the dirt, both in the same inning — was making agape the standard formation for mouths all around Shea Stadium.

• “What can I tell you, he’s the greatest. We’ll see that all year, though, not just today.”

— Davey Johnson

• “That was a great play. In fact, that was it right there because that ball was basically down the right field line for a double and a run would’ve scored. He made a hell of a play on it. In fact, I tried to get over to cover first for the double play. Hell, he even ran over to first. He wanted the ball for the double play.”

—Doug Sisk, bailed out by Keith on the play the reliever described

• “I’ve seen more great plays since I’ve been here than I’ve ever seen. I think everyone knows how great Keith is.”

—Bruce Berenyi, who’d been a Met for all of two starts

• “That’s the best-fielding first baseman I’ve seen since Gil Hodges.”

—Murray Hysen, my friend Jeff’s father, sitting in the Field Boxes behind first base and speaking for those whose frames of reference extended back a ways

I didn’t see Gil Hodges play first base, but I have been watching first basemen for 54 seasons. I’ve never seen a better fielding first baseman than Keith Hernandez. If Shea Stadium were still standing, you could fill the joint with people who’d swear the same thing.

10. Keith’s not quite seven seasons as a Met were golden. They shimmered only more in memory as 1989 receded into the rearview. Just as the 1969 Mets came to represent something wistful for those of us stuck watching the 1979 Mets, the failure of the Mets of the early 1990s to sustain the previous decade’s hard-won winning ways cast the 1986 Mets in an impossible role. I remember sometime in the smoldering aftermath of 1993, when the best Mets highlights were to be found by cueing up A Year to Remember on your VCR, a newspaper story that caught up with the recently retired Keith Hernandez. Keith said Mets fans still called out to him on the street in Manhattan that they needed him to come back. Keith being Keith scoffed that he was too old and in no shape to be of any such help. Me being me, I was thinking that if I saw Keith on the street in Manhattan, I would have called out to him that we needed him to come back.

11. During the interregnum between the twilight of Keith the Met ballplaying icon and the emergence of Keith the Met broadcasting icon, Keith Hernandez became a sitcom guest star for the ages. Never mind that Elaine Benes didn’t think the third base coach would be waving Keith in. Never mind that Newman and Kramer were enjoying a beautiful afternoon in the right field stands when their day was ruined by a crucial Hernandez error. Never mind the serendipitous meeting in the health club locker room or what a big step in a male relationship one man asking another man to help him move furniture is. The key to “The Boyfriend,” the Seinfeld two-parter that put Keith Hernandez on a whole other psychic map was Mrs. Sokol, the unemployment official who informs George Costanza that she didn’t miss an inning of the 1986 Mets and who will bend the rules and extend George’s benefits if he can produce Keith Hernandez in her midst within the hour. Mrs. Sokol was every one of us in New York in 1986 with our eyes and/or ears glued to every game. Mrs. Sokol was every one of us as of 1992, when The Boyfriend aired, missing how wonderful it was to have been a Mets fan a few short years before, clinging only to our autographed baseball and the slim chance the strange man begging for an extension will bring Keith Hernandez to our office in sixty minutes or less. It was worth a shot in the dark to believe Keith Hernandez could become part of our lives again. He was, after all, Keith Hernandez.

12. The Keith Hernandez who re-entered our daily consciousness in 2006 (for those who didn’t find themselves thinking about him as a matter of course already) wasn’t exactly the Keith Hernandez on whose every swing, dive or word we hung twenty years earlier. He couldn’t be. That Keith was Mex. The new Keith explained on the air over SNY once that Mex was his ballplaying persona. Mex was intensity personified. Mex needed to bear down in order to compete, to win. Once there were no more games to contest, Mex wasn’t necessary. Neither, eventually, were the Marlboros, thank goodness. The Keith of the booth was an evolved Keith. Older, of course. Goofier, I suppose. The intensity that made him a must-listen on the local news at 11 o’clock and a must-read in the paper the next morning had evaporated. The Keith of the booth wasn’t getting an at-bat in the eighth between Backman and Carter. The Keith of the booth, between Darling and Cohen, could sit back and relax. I have to admit, it took some getting used to.

13. Beautifully, though, Keith was still Keith. Evolved, not overhauled. Goofy at times, but no less fascinating. And still a ballplayer’s ballplayer when ball was being played. I used to roll my eyes a little that Keith Hernandez spoke in the present tense — “I’m a first baseman” — when describing the game played in front of him. Yet once a first baseman, specifically the best-fielding first baseman most of us had ever seen, always a first baseman. Same for the hitter we still wish we could have up in the clutch, never mind that the only physical activity in which we’d seen him engage lately was a rerun of him stretching prior to meeting Jerry and that chucker George. Keith the announcer is still very much in the game.

14. Next game Keith is working, pay close attention when the broadcast begins. Keith really is working. He notices things and he tells us. He notices the pitcher is warming up off the rubber if that, in fact, is what he’s doing and wonders why he’s doing it (it happened with Sandy Alcantra in Miami recently). He’s all over the center fielder shaded this way or that. He’s analyzing the size of the lead taken off first base, both from the perspective of an eleven-time Gold Glover and as someone who plotted to go first to third on a single. The goofiness is still abundant, and it’s charming as all get out — who doesn’t want to know what Hadji is up to? — but you get your baseball’s worth from Keith Hernandez. As masterful as Gary Cohen is at all facets of announcing and as insightful as Ron Darling is when it comes to pitching specifically and life occasionally, the booth is never quite whole without Keith. It’s certainly not the highbrow cocktail party that gets a wee bit out of hand by the middle innings. Just as we cherished the Keith in the middle of the Met order, we cherish every bit as much the Keith in the middle of this lineup. If he’s a little impatient around the margins with modernity or a little anxious to adios and beat traffic or drifts off into Keithland for a pitch or two, so be it. He always comes back.

15. No. 17 is being lifted up where it belongs because Keith Hernandez has done it all for this franchise. He never stopped being Keith, not in a Met championship run, not in Met absentia, not on the Met air. If the less than seven full seasons of playing somehow didn’t seem impressive enough to whoever made number-retirement decisions for decades, the almost forty years of embodying what we wanted the Mets to be pushed him over the top. Like Ralph Kiner might say, the sum of Keith Hernandez definitely adds up to more than his totals.

16. So we thank the number 17 for its service to every Met not named Keith Hernandez who wore it, from Don Zimmer in 1962 to Fernando Tatis in 2010. Some of you did it quite proud and we appreciate it. We also acknowledge utilityman Keith Miller and journeyman Keith Hughes for having played their best for us. But just as there’s truly only one No. 17 to us now and forever, there’s also only one Keith in these parts.

17. He’s Keith Hernandez. But you knew that already.

I engage in a detailed discussion regarding Keith Hernandez with Murray Hysen’s son Jeff on the new episode of National League Town. Listen to it here or via any of approximately 17 outstanding podcast platforms.

Not that it takes away AT ALL from this fantastic piece, and I’m guessing there is may be photographic evidence of Keith being a Marlboro man, but for the record…I believe Keith smoked Winstons.

At a Meet the Mets signing before the first Shea Subway Series game in ‘98, Keith signed a pack of Winstons – after acknowledging that was his brand – for my brother which he still displays on a shelf.

Whatever was his brand, he kicked the habit. Thankfully our habit of seeing and hearing and appreciating Keith will never be kicked.

Winstons were said to taste good like a cigarette should, and Keith had good taste.

We still need Keith to come back.

So…new FAFIF t-shirts?

Regarding Points 12-14, have you (ummm) listened to (aaaahh) them lately (MMMMM)? I realize GKR are Met royalty, a thousand times better than the Yankee booth and it’s blasphemous to bring up such matters (especially on this day)…but they’ve truly become (OHHHHHH) borderline unbearable.

Agreed — it’s blasphemy, especially today.

I am beginning to agree with you, Rudin1113. Gary, especially, is becoming borderline obnoxious, and it’s too bad, because he used to be professional. Now he is just a pun-making know-it-all who always has to prove he is the smartest and funniest in the class.

My favorite booth moment was when Keith threw a sharpie and broke the camera lens. Come on, that was classic TV…

Nice piece, pretty boy.

His book, I’m Keith Hernandez says it all.

I recommend this one also:

https://www.powells.com/book/pure-baseball-9780060925918

[…] No. 17, Up Where It Belongs » […]

Gary and I are the same age and still he often forces me to say “OK, Boomer”.