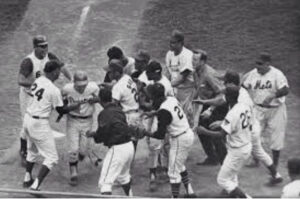

It’s a Tuesday night in July of 1970. It is the twelfth inning of a 4-4 contest. Pete Rose is on second. Jim Hickman singles into center field. Rose motors around third base. Amos Otis fires to the plate. Rose keeps coming home, regardless that Ray Fosse is blocking his path. The on-deck batter Dick Dietz gesticulates toward the baserunner that he needs to get down and slide. The baserunner has his own idea of what that means. Pete Rose is a bull in Riverfront Stadium’s china shop. Fosse is a cape to be rushed through. All the metaphors collide. Rose bowls over Fosse. The runner is safe, and the National League has won the All-Star Game, 5-4.

It was the Tuesday night that hooked me on the All-Star Game for the next 55 years. It was to be played hard, played by the best, played all night if necessary, played without regard to consequences for opponents who got in the National League’s way. The National League was the league the Mets were in — the Mets’ manager, Gil Hodges, ran the show; the Mets’ ace, Tom Seaver, started the show; the Mets’ shortstop, Bud Harrelson, would trot back to his position for the thirteenth had Otis and Fosse combined to nail Rose — therefore on this Tuesday night and in every primetime showcase like it over the next 55 years, the National League would be my team. Every National Leaguer, even those I rooted against as a matter of course, were was my guy. Every American Leaguer, whatever degree of unawareness I held for most of them as the seasons went by, was a guy who had to be bowled over or at least defeated. For all the pageantry and provincialism that’s informed my fluctuating year-by-year interest since, that’s the equation that’s kept me coming back midsummer after midsummer.

It’s a Tuesday night in July of 2025. It is not the tenth inning. It could be, but there is no tenth inning, despite the score sitting at National League 6 American League 6 after nine. I have tuned in and stayed tuned in. I have always tuned in. I will probably always tune in. I have been rooting on this Tuesday night for the National League to beat the American League. When I was a kid, when I was a teen, and as I was entering adulthood, the National League almost always beat the American League. The National League had been beating the American League in All-Star Games since I was born. National League victories were my birthright. In my twenties, an NL victory was no longer a sure thing. By the time I turned thirty, the American League had been winning dependably for several summers. Except for a few oases of what I considered normality, my life since then has been pocked annually by the AL finding a way to win the All-Star Game…or the NL finding a way to lose.

At the end of the sixth inning this Tuesday night in July of 2025, the National League has this thing in the bag. Or so I almost think. Three of the four Mets who are on hand have seen to it that we — my team, my league — will win have already played. There’s a moment, in the fourth, when David Peterson grounds Aaron Judge to Francisco Lindor, who throws to Pete Alonso for the out. I couldn’t have adored it any more had that been, say, Bobby Murcer grounding out to Buddy on a pitch thrown by Tom. The All-Star Game was a throughline for me. Mets besting Yankees. National Leaguers topping American Leaguers. Little moments within bigger moments on nights when this was the only baseball anywhere. It didn’t count. It counted as much as I wanted it to.

At the end of the sixth inning this Tuesday night in July of 2025, the National League has this thing in the bag. Or so I almost think. Three of the four Mets who are on hand have seen to it that we — my team, my league — will win have already played. There’s a moment, in the fourth, when David Peterson grounds Aaron Judge to Francisco Lindor, who throws to Pete Alonso for the out. I couldn’t have adored it any more had that been, say, Bobby Murcer grounding out to Buddy on a pitch thrown by Tom. The All-Star Game was a throughline for me. Mets besting Yankees. National Leaguers topping American Leaguers. Little moments within bigger moments on nights when this was the only baseball anywhere. It didn’t count. It counted as much as I wanted it to.

In the bottom of the sixth at Truist Park, my team’s home stadium for one night and one night only, Pete comes to bat with two runners on base and the NL ahead, 2-0. Kris Bubic is pitching for the American League. Kris Bubic is from the Kansas City Royals. I didn’t notice Kris Bubic over the weekend when the Mets were in Kansas City. Truth be told, I’d never heard of Kris Bubic. It’s not the summer of 1970 when I considered it my duty as a seven-year-old to know every star in baseball. I follow the Mets mostly. The stars I need to know I know. The stars I don’t know tend to be evanescent. Every year at these affairs there’s a slew of names that are new to me. Maybe they’ll be back next year. Probably not. but I will.

Still, Bubic is the pitcher, and Alonso is the slugger. Pete’s a big deal on the All-Star stage usually because he takes swings in the Home Run Derby. The Home Run Derby can be quite entertaining if Pete Alonso is in it. He’s the only reason I’ve watched it in recent years. It didn’t exist in 1970, so I’ve never developed an automatic affinity for it. Pete won it in 2019 and 2021. I was pumped. He didn’t enter it in 2024. I barely noticed it. Nonetheless, it’s given Pete a certain midsummer cachet, thus when Pete Alonso connects off Kris Bubic for a three-run opposite-field homer, it’s a big Polar deal. That’s Pete Alonso! That’s the guy who shines in the Derby! To me, that’s the first baseman for the New York Mets! A Met has put the NL up, 5-0! Two batters later, Corbin Carroll, one of those stars I know and one of those guys who’s one of my guys for a night, homers with nobody on and the NL is up, 6-0, and I’d say I’m a kid again, except I’m always a kid watching the All-Star Game. But this time I’m a happy kid, because for only the eighth time in the past thirty-seven editions of this thing, we are going to win.

And just when I’ve decided the National League has this thing in the bag, I shudder, because you just can’t allow yourself to think that way about a game you take seriously. I’m taking this All-Star Game seriously. I take every All-Star Game seriously. The rest of the kids from 1970 or whenever grew up and grew realistic. The All-Star Game is about everything but winning, about everything but upholding the honor of the senior circuit, about everything but associating yourself with the league you consider innately better and purer and whatever other qualities you deign to ascribe to one entity over another. Logically, I understand the All-Star Game has been continually watered down as a test of wills. The rival leagues have blobbed into one shapeless entity where everybody shakes hands or hugs. The Mets just played Kansas City in the regular season, for goodness sake. Every team uses a DH. Two of the Met players in whose designation as National League All-Stars I reveled, Lindor and Edwin Diaz, were American League All-Stars not that long ago. This is all branding and marketing. Nothing is sacred anymore, certainly not the Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

And just when I’ve decided the National League has this thing in the bag, I shudder, because you just can’t allow yourself to think that way about a game you take seriously. I’m taking this All-Star Game seriously. I take every All-Star Game seriously. The rest of the kids from 1970 or whenever grew up and grew realistic. The All-Star Game is about everything but winning, about everything but upholding the honor of the senior circuit, about everything but associating yourself with the league you consider innately better and purer and whatever other qualities you deign to ascribe to one entity over another. Logically, I understand the All-Star Game has been continually watered down as a test of wills. The rival leagues have blobbed into one shapeless entity where everybody shakes hands or hugs. The Mets just played Kansas City in the regular season, for goodness sake. Every team uses a DH. Two of the Met players in whose designation as National League All-Stars I reveled, Lindor and Edwin Diaz, were American League All-Stars not that long ago. This is all branding and marketing. Nothing is sacred anymore, certainly not the Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

But I want to believe it is, and I want to believe the National League can maintain the 6-0 lead it has built as the seventh inning approaches. Everybody is wearing his team’s actual uniform, which is a welcome throwback. We have just seen a multimedia tribute to Henry Aaron, beamed live from the outskirts of Atlanta, so maybe that, too, is a sign that we’re going to have a 1970-style result if not 1970-style climax. Hammerin’ Hank started in Cincinnati 55 years ago. Charlie Hustle replaced him in the NL lineup.

Henry Aaron is gone. Pete Rose is gone. Fifty-five years is a long time. It’s 2025. Despite a couple of touches that tap you on the shoulder to remind you of what All-Star Games used to be — is that Joe Torre, who played alongside Hank and Pete at Riverfront that night in 1970, hanging out in the AL dugout? — it’s a far different game these nights. Gil Hodges used five pitchers over twelve innings. Dave Roberts in the seventh is up to his eighth, Adrian Morejon. Adrian Morejon is on the Padres. The Mets haven’t played the Padres yet in 2025, so whatever awareness I’d built up of his existence previously has faded. He could be Kris Bubic for all I know.

Morejon, I learn, isn’t the National Leaguer I want protecting a 6-0 lead. He walks two American Leaguers and gets replaced by Roberts’s ninth hurler, Randy Rodriguez. Rodriguez, of the Giants, gives up a three-run home run to Brent Rooker, of the Athletics. From 1968 to 2024, that would have had special resonance for fans in the Bay Area, except now, while the Giants are still San Francisco, the Athletics aren’t Oakland. Technically, they aren’t anywhere. This is the sort of thing that happens in baseball in 2025. Another thing that happens is the American League dragging this thing halfway out of the bag I thought it was in. The NL leads only 6-3.

Didn’t Trevor Hoffman blow one of these back in the “this one counts” era, when the All-Star Game was supposed to determine home-field advantage for the World Series? They came up with that doozy because one year, in 2002, the All-Star Game limped to a tie in the ninth, and the mangers — one of them Joe Torre — ran out of pitchers. Players had taken to bowing out of going, and players who played had taken to bolting the premises once removed, so something had to be done. In 2006, when the Mets appeared a marvelous possibility to represent the NL in the World Series three months hence, I cared even more that the NL win the All-Star Game. Hoffman blew it for us. That we didn’t make the World Series in 2006 remains immaterial in my grudgeholding.

Didn’t Billy Wagner blow one of these, too? That was in 2008, at Yankee Stadium. We couldn’t have a Met blowing an NL win at Yankee Stadium, but there he was, being every bit the big game bet Trevor Hoffman was two years earlier. In a couple of weeks, Billy Wagner will join Trevor Hoffman in the Hall of Fame. They were both great relievers, except on midsummer nights when many were watching. I was gonna say “when everybody was watching,” but fewer and fewer watch the All-Star Game every year since 1970. Me, I keep watching, because I watched when I was seven, when Pete Rose bulled Ray Fosse out of his way, and the NL won in twelve. I never had to be marketed to again. My brand loyalty was set.

Randy Rodriguez remained on the mound long enough to give up another American League run. Now it was 6-4, NL. Tylor Megill’s brother Trevor, our tenth pitcher, got us out of it. Managers no longer manage to win the All-Star Game. Managers manage to ensure everybody gets into the All-Star Game. David Peterson could have gone another inning, but the each out any one pitcher records is one less somebody else can’t. I wish my day camp counselors in the summer of 1970 ran our games with such attention to individual feelings. I’m glad Gil Hodges ran the All-Star Game as he did.

Two more pitchers got the NL through the eighth intact. Two more pitchers did no such thing in the ninth. The second of them was Diaz, who didn’t pitch badly, but he came in with a runner on second and one out, our league’s lead whittled down to 6-5. Matt Olson made a helluva play on a hot Jazz Chisholm grounder, much as Pete Alonso made a helluva play on a hot Jarred Kelenic grounder last September. Then, Diaz didn’t cover first and the entire Met season nearly came tumbling down as a result. Now, Diaz covered first, and a second out was ensured. Progress. But Bobby Witt, the runner Edwin inherited, crossed over to third, setting him up to come home on Steven Kwan’s ensuing dribbler, no bowling into the catcher necessary. We were all tied up at six. Kwan proceeded to steal second because everybody proceeds to steal second when Diaz is pitching (unless he has Luis Torrens, Francisco Lindor and replay review working in his favor). Randy Arozarena was up. Edwin struck him out by first throwing a borderline ball on oh-and-two and then patting his head while rubbing his tummy, the signal for the robot ump to change the call of the human ump. This All-Star Game tested that same system we saw in Spring Training. It got Edwin out of trouble, so I’d say it worked.

The National League didn’t score in the bottom of the ninth. While the half-inning was in progress, the telecast showed Pete Alonso taking swings in a batting cage. My first instinct (and, I’m pretty sure, those of the uninformed announcers) was to admire Pete’s work ethic. He was out of the game, but he was using his time in a ballpark to stay sharp for the second half of the regular season. What dedication! Then, in a flash, I remembered that I didn’t have to worry about whether Diaz was going to have to pitch the tenth — Roberts had used every pitcher — because if the NL didn’t score right here and now, there’d be no tenth inning. Alonso was warming up for what loomed just over the horizon.

There would be no 2002-type tie. This time what would count would be a mini-Home Run Derby. They even had a cutesy name for it: the swing-off, like the page-off in 30 Rock, except no young lady in a blazer and a skirt would run through the halls ringing a bell. Or maybe she would. We’d never had a swing-off to conclude an All-Star Game, but after Brendan Donovan fouled out to end the ninth, we would.

Apparently, Roberts and his counterpart, Aaron Boone, had been instructed before the game to choose three sluggers to come out and take three swings versus their own league’s batting practice pitcher. But not just any three sluggers. If certain sluggers had already dressed and boarded private jets, they wouldn’t be summoned to return. No Ohtani. No Judge. No kidding. Nonetheless, it was all very festive the way it was presented. Each manager revealed to Kevin Burkhardt who his sluggers were gonna be. One of Roberts’s, batting third, was gonna be “the Polar Bear”. Pete Alonso is so famous in these circles that there’s no need for elaboration.

The swing-off immediately occupied a space between “ohmigod, they’re really doing this!” and “what the [bleep] is going on here?!?!” It was better than a tie. It was better, maybe, than a ghost runner on second, especially since there was nobody left to pitch. In 2008, at Yankee Stadium, hours after Billy Wagner couldn’t retire the AL without a ruckus, the leagues pushed the envelope of availability for fifteen innings until the NL was ready to put David Wright on the mound for the sixteenth. It strained credulity that position players were going to pitch in an All-Star Game then. Now? When it’s mildly surprising that pitchers are allowed to pitch at all ever? No chance anybody takes a chance with anybody’s arm.

Goodbye, All-Star extra innings. Goodbye, win at all costs. Goodbye, this particular legacy of Pete Rose. Like almost everything about Pete Rose, this legacy required parsing. No player burned more to win. You had to love that, especially if you were seven and he was on your team for one night. But was the All-Star win something worth wrecking Ray Fosse’s season over? Fosse’s shoulder was separated and he was never the same player again. That, however, was how the game was played in those days, the All-Star Game included. Catchers don’t block plates sans ball anymore. It’s been legislated from existence. It’s not necessarily a bad idea if you think about it. Or maybe you don’t wanna think about it. Maybe you just want everybody to be hellbent to win every night, All-Star Games included.

Hello, swing-off. Hello again, Brent Rooker of the Athletics from nowhere. Rooker got the AL back in the game, then he got the AL off to a 2-0 swing-off lead. The NL countered with Kyle Stowers of the Miami Marlins. The Mets last played the Marlins in April; forgive me for a lack of Kyle Stowers consciousness. He got one for the NL. Up for the AL came Arozarena. Only one of his swings was for a homer (with no outfielders tracking balls, it was hard to tell at first what was or wasn’t going out), so the AL now led, 3-1. The NL’s second slugger was gonna be Kyle Schwarber. I’m not in the habit of rooting for Phillies, but on Tuesday nights like these, there are no Phillies, no Marlins, no Braves. We are one big National League family.

Cousin Kyle bombed his BP pitcher, a fellow from the Dodgers named Dino Ebel — I swear I thought Joe Davis kept saying “see no evil” — with each swing he took. On Schwarber’s final lunge at glory, when he went down on one knee to get ALL of it, my instinct was to worry that he could get into bad habits swinging like that. Then I remembered swinging like that is what was encouraged in a home run derby, and, besides, what do I care about Kyle Schwarber’s habits being good? All I cared about in the moment was the NL led the AL in the swing-off, 4-3.

Which meant I cared about two things next:

1) What the AL’s final batter, Jonathan Aranda of the Rays, was going to do in his three swings.

2) The fate of the NL’s final scheduled swinger, the Polar Bear.

My NL instincts demanded Aranda — never mind that he’d played in the preceding game; I’d already forgotten who he was — must be foiled completely by his own BP pitcher, some dude Boone brought from the Yankees. My Met instincts kind of wanted to see Alonso come up and win the damn thing for us. For all of us. A little of me worried Pete would pick this moment to go into a home run drought, but more of me hoped he would ice it for the NL, and lay claim to the MVP trophy.

Alonso hit that three-run homer in the sixth. That was the biggest hit of the night, at least until Rooker hit one of his own. But if the National League won, they’d have to give the prize to Pete, wouldn’t they? And if Pete didn’t get to hit in the swing-off? There was no precedent on which to rely here. This was all new, all very postmodern.

Jonathan Aranda almost hit one ball into the seats. Had Truist Park not been designed with a brick wall over its right field fence, he would have, but the architects probably weren’t thinking about a swing-off someday deciding an All-Star Game. Or perhaps they were incredibly prescient. Either way, Aranda went 0-for-3, which meant the NL won the swing-off, 4-3, and the game itself, 6-6, not a typo. Kyle Schwarber, it occurred to me, was evoking the spirit of his Phillies’ predecessor Johnny Callison, who won the 1964 All-Star Game for the National League with a ninth-inning three-run blast, what we would come to call a walkoff homer. That game was at Shea Stadium. Callison grabbed a Mets batting helmet to do his swinging, because the powers that be weren’t fanatics (or Fanatics) about who wore what way back when. The players, however, were fanatics about competing. Callison hit his game-winner off Dick Radatz of the Boston Red Sox. Radatz was known as the Monster. Radatz was trying to get him out. Ebel was attempting no such thing versus Schwarber.

So, no, this wasn’t anything like Johnny Callison, but they gave Kyle Schwarber the MVP trophy, anyway. He didn’t do anything of note in the actual All-Star Game, but we all just saw what he did to decide the All-Star Game. My Polar bias notwithstanding, I couldn’t argue with Schwarber being declared Most Valuable. I also couldn’t quite get behind it, same as I guess I’m glad the National League won its eighth All-Star Game in the past thirty-seven, but did they? They won on a swing-off. There had no been such thing as a swing-off a half-hour earlier. Now we were determining league supremacy by it.

So, no, this wasn’t anything like Johnny Callison, but they gave Kyle Schwarber the MVP trophy, anyway. He didn’t do anything of note in the actual All-Star Game, but we all just saw what he did to decide the All-Star Game. My Polar bias notwithstanding, I couldn’t argue with Schwarber being declared Most Valuable. I also couldn’t quite get behind it, same as I guess I’m glad the National League won its eighth All-Star Game in the past thirty-seven, but did they? They won on a swing-off. There had no been such thing as a swing-off a half-hour earlier. Now we were determining league supremacy by it.

Huzzah?

Not quite. After fifty-five years, I’m out. Not out of baseball, and not out of the All-Star Game as something I tune into or something I obsess on for a few minutes at a time every July in terms of what Mets are named and what Mets aren’t (think Juan Soto couldn’t have done what Schwarber did?). I mean I’m out on taking its result seriously. I may have been the last adult in America to get the memo that it didn’t matter, the last to sit through all the pregame folderol — “they could have played three innings by now,” I told Stephanie during the extended introductions — because I was still anticipant that the NL was going to beat the AL. Even in the years when the AL seemed designed to beat the NL with its fewer teams and deep well of offense, I still looked at the Midsummer Classic the way I did when I was seven. On some level within me, this mattered. The National League mattered. The American League, as much as I disdained it, mattered. A game between the best of each league mattered. Interleague didn’t ruin that. Uniting the umpires and everything else under the MLB umbrella didn’t ruin that. The swift movement of players from team to team regardless of league didn’t ruin that.

The swing-off ruined that. The swing-off could rightly be viewed as “fun,” within the context of what is and what has always been an exhibition, but as someone rooting the way I have for so many midsummers, I heard myself ask myself, as I watched every visible National Leaguer jumping up and down for joy, “What the hell does fun have to do with the Major League Baseball All-Star Game?” To this curmudgeon, the swing-off proved nothing, other than Kyle Schwarber is really good at hitting the pitches Dino Ebel tees up for him. Mazel tov to both gentlemen. Had Pete Alonso been the batter to take those swings and send them beyond the fence, I would have loved him doing so, but I don’t think it would have changed how it all landed on me.

From cheering Pete Rose scoring in 1970 to awaiting Pete Alonso swinging in 2025, I was into it. It was a good run, but at last it’s barreled into a sense of dismay I find immovable.

It was the doofiest thing I’ve ever seen. Why wasn’t Cal Raleigh selected to be in the swing off? Doesn’t he have oodles of HRs and didn’t he win the HRD? And we never got to see Pete, who was left -ing off in the dugout. But that 3-run homer was pretty cool.

I was OK with the Land of Make Believe ending, except, to quote Dustin Hoffman’s Father in The Graduate, the whole thing seemed pretty half baked.

How did it come down to some guy I never heard of with 11 Home Runs? Was there a choice? Did anybody know the rules beforehand (surely not anyone on TV)?.

BTW, I was camping in Kapuskasing Ontario (look it up) on a 2/3 Cross-Canada trip the night of the 1970 All Star Game, listening on the radio. It’s a lasting memory. I compared notes via text with one of my camp-mates this AM.

Was there nobody better than that last AL hitter available or willing to swing for homers? A poor selection, even before anyone took their turn at bat. There’s a reason the AL manager’s name started with Boo.

Greg, from your penultimate sentence I would guess that, if Pete had come to bat and won it for the NL with anywhere from 1 to 3 BP HRs, you’d be feeling differently. Not necessarily feeling that the purity of baseball has been restored, but at least satisfied that a powerful Met had won things for the NL. By nature of the silliness of a ‘swing-off’, even Pete winning it would have been goofy, just like Pete is goofy. But there would have been good vibes all around. Instead, we were saddled with an ersatz MVP who went 0-2 in the actual game facing actual All-Star pitchers, while Pete’s 3-run HR off an actual All-Star pitcher was the main reason the NL didn’t lose on the failures of their Western-division relievers. Pete getting robbed of the MVP was as much as anything a statement about people’s poor memories, recency bias, and vaunting of the showy but vapid in our culture.

Right after the game, the announcers threw it to commercial, saying that we will be back with the presumed MVP, Pete Alonso. Then they come back with the Phillie. Very disappointing, as I still root for Mets in the ASG. even though overall I could not care less.

The Aaron tribute sucked, as they barely showed the HR, and they barely showed Aaron. Just another pyrotechnics event put together by people who have never even heard of Hank Aaron.

You play a game for 3 hours under one set of rules and then determine a winner under a totally different ser of rules. That’s horseshit. It’s like penalty kicks settling a soccer match or a shootout in a hockey game. No thanks.

And then, ti give the game MVP award to a guy who made his mark hitting pitches thrown by a 59 year old batting practice pitcher is double horseshit.

The All-Star game ain’t what it was when I was a kid and guys like Stan Musial and Ted Williams would play the whole game.

Apparently they had to do the whack-off. Both sides were out of pitchers.

Apparently, the swing-off has been in place the last few years, so the managers knew they could use all their players by the end of the 9th inning. And apparently, the hitters were chosen days before the game.