They changed personnel. They changed locale. Their results didn’t much differ. The post-trade deadline New York Mets lost, 4-3, at Citi Field on Friday night to a San Francisco Giants team that looked familiar, and not just because they were who the Mets took on last weekend, the last time the Mets won a game. Wilmer Flores, who was a Met in the company of Dom Smith, who was a Met in the company of Joey Lucchesi, who was a Met in the company of Jose Butto, who was a Met until the other day, all represented the opposition. Perhaps it confused the players who were wearing Mets uniforms. The whole thing required ten innings to sort itself out. Smith drove in what proved the winning run. There was a time that would have been swell. There was a time the 2025 Mets were swell.

That time can return, you’d think. It’s still mostly the same guys who were in the midst of a seven-game winning streak a week ago. It’s still mostly the same guys who’ve occupied first place more than they haven’t. Not that they occupy first place at the moment, not after the Phillies won while the Mets were losing their fourth in a row. This is the Mets’ second four-game losing streak since they lost seven consecutive in the middle of June. There was also a three-game losing streak in there somewhere. These are not the trends one associates with a first-place team.

To regain the momentum that elevated them to/near the top of their division, the Mets got busy as the deadline approached. We’ve now seen two of the three relievers recently obtained in action, Gregory Soto twice on the West Coast (once for better, once not so much), Ryan Helsley Friday night at home. Helsley is accompanied by a hellacious entrance music and light show, though once you’ve enjoyed your incumbent closer’s entrance music and light show, all you really want to see are outs recorded without fanfare. Helsley rang those bells successfully, striking out three batters in the ninth to keep tied a game that the Mets had just evened, the same one Edwin Diaz would lose, despite all those trumpets. The new late-innings specialist gave up no runs, so that was a small victory within the larger defeat. Tyler Rogers has yet to pitch, so we’ll wait on appraising his first tiny sample size and whatever flourishes soundtrack his appearances.

We also traded for a center fielder at the deadline, Cedric Mulllns, late of the Baltimore Orioles. I want to call him Moon Mullins, because I’m pretty old, but his sanctioned nickname, per Baseball-Reference, is The Entertainer, which makes more modern sense. Cedric didn’t get much of an opportunity to entertain his new audience Friday. He pinch-hit with two out in the bottom of the ninth to no great effect, and was not moved along meaningfully by his new teammates when he returned to the basepaths as the Mets’ unearned runner in the bottom of the tenth. In between, he played an inning in center field, notable because, man, do the Mets need a center fielder, specifically one who can hit.

They didn’t need to find a new center fielder to play center field. They’ve had themselves a fine one all along. Center field has been well covered this year primarily by Tyrone Taylor. The 70% of the earth being covered by water equation disseminated by Ralph Kiner on behalf of Garry Maddox pretty much applies to how Tyrone gets around out there. If David Peterson is an ironman in this age when our mouths hang agape for solid six-inning starts, Taylor is a veritable Gold Glover for tracking almost everything down when he plays. Of course he doesn’t play as often as a regular might because somebody’s gotta hit. Taylor in 2025 has been a center fielder who has barely done a lick of that.

Listen, somebody’s gotta hit from every position within the Mets’ lineup. Friday night, we got a little hitting from Pete Alonso, including his twenty-third home run, which put the Mets on the board when they’d trailed, 3-0, and the deep fly ball that caught the Mets all the way up to 3-3; a little hitting from Juan Soto, when a ball he grounded up the middle caromed off the mound and became an essential eighth-inning RBI; and a little hitting from Francisco Lindor, who preceded Soto’s somewhat lucky shot (Juan’s hit into enough hard outs) with the single that helped build the Mets’ second run. A little hitting from the Mets’ Biggest Three is more than they’d been receiving in San Diego. A little hitting isn’t going to do it.

A little hitting would look fantastic from Taylor. A lineup featuring three slugging stars and a strong second line of support, should be able to carry a glove-first, bat-last fella. Tyrone, who might hit ninth if the pitchers still swung, has taken the defense dispensation to extremes. On June 21, Taylor contributed two hits to the Mets’ 11-4 romp in Philadelphia. Since then, across 28 games, he’s collected six hits in 67 at-bats. In the parlance of trying to get off the Interstate, Tyrone’s been stuck on a state road since summer kicked in.

That, along with the Mets’ effort to fit all their slight irregular square pegs into reconfigured round holes, helps explain why he’s shared much of the available center field playing time with Jeff McNeil, who’s not a center fielder but does get hits. Jeff’s played center well enough. Jeff’s played it like he plays it like he plays every position, by scowling it into submission. You’d rather have McNeil at second base, even if that means you won’t have Brett Baty at second, which you may or not want, anyway, but you would like to get Baty in there somewhere without having to sit Ronny Mauricio, who’s more or less the third baseman now, if it’s not Baty or Mark Vientos, who’s probably the DH, except when it’s Starling Marte.

In the literal middle of all this, welcome Mullins, the new lefty-swinging center fielder, complementing righty Taylor, if we’re being kind. Cedric had one truly excellent season as an Oriole, then one somewhat less excellent, then a couple that got progressively more unimpressive. I don’t want to say “worse,” because I’m trying to stay positive. He’d been hitting well before getting traded, and he can make the plays in center. Maybe that’s enough to make a significant difference for the Mets. Or maybe we’re gonna get lifted by the players we expect to do the heavy lifting, and anything we get out of Cedric will constitute a small but vital boost.

Acquiring Mullins got me to contemplating Met center fielders through time as a species and it occurred to me that almost never is a Met center fielder the player who is front and, well, center for this franchise. We’ve had some splendid ones, a couple who could do it all, more than a few who could some things wonderfully, but in a sport not to mention a city where center fielders have been eternally romanticized, have the Mets ever been “led” by theirs?

A little, maybe. Join me on a selectively crafted and not necessarily thorough 410-foot trip to center, from our beginnings to right now. If the apple of your eye or bane of your existence isn’t explicitly shouted out, you can trust that their names at least flitted through my consciousness amidst this exercise.

Richie Ashburn, a Hall of Fame center fielder, was our first All-Star and perhaps spiritual leader, but he played a lot of right in 1962 before retiring.

Jim Hickman has a claim on most accomplished player in the portion of Mets history that ended prior to 1969, however faint that praise lands, but he also got moved around quite a bit (and, in real time, wasn’t considered someone making the most of his potential).

Cleon Jones became a regular in the majors as the Mets’ primary center fielder in 1966. His marvelous Met future awaited in left.

Don Bosch was, in 1967, going to give the Mets the true center fielder they’d lacked from their inception. He didn’t.

Tommie Agee broke out for two seasons of sensational production from every angle of the game in 1969 and 1970, and that alone is worthy of his place in the Mets Hall of Fame. Honestly, Game Three of the 1969 World Series should have certified his induction. But the Tom who led the Mets in Agee’s day didn’t play center.

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays.

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays.

Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser.

Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser.

Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.)

Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.)

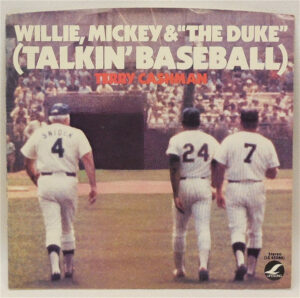

Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee.

Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee.

Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.

Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.

Lenny Dykstra gnawed into Mookie’s playing time, turning Wilson into a part-time left fielder. From 1985, though the platoon he forged with Mookie to win a World Series, to the Sunday afternoon in 1989 he was sent from the visitors’ to the home clubhouse at Veterans Stadium, Nails could be really nails. Never quite made the case to be a regular in New York, though. Philly was a different story, as have been as his post-playing let’s call them adventures.

Lance Johnson (doing some skipping over some short-term solutions and lesser ideas) was a dynamo in 1996. Led our league in hits (227) and triples (21). Still owns both single-season Met records. Probably always will. Stole fifty bases. With Todd Hundley and Bernard Gilkey, stood as the reason to keep watching a furshlugginer ballclub. Traded in 1997.

Brian McRae was who we got for Lance Johnson, and who we’d trade for Darryl Hamilton.

Darryl Hamilton delivered one huge base hit in the 2000 postseason. Sometimes one huge base hit is all you need.

Jay Payton had already usurped center field from Hamilton and the others who’d had their turn-of-the-millennium moments as 2000 grew successful. Big prospect. Long career. Didn’t really and truly click as a Met except in spots. Certainly didn’t last as a Met.

Mike Cameron put together a quietly gaudy season in 2004. Thirty home runs. Twenty-one steals. Exciting defense, which is to say he liked to play shallow but usually caught up to balls. With Cliff Floyd, installed “The Way You Move” by Outkast as that season’s “L.A. Woman,” not that that’s much remembered, because 2004 wasn’t 1999. And Cameron wasn’t long for center field.

Carlos Beltran…he’s Carlos Beltran. He meant a lot of things to the Mets as soon as he signed for seven years in 2005, beginning with ending Mike Cameron’s tenure in center field, and ending with beginning Zack Wheeler’s affiliation in Flushing. As good an everyday player as we’ve ever had. Our all-time center fielder by consensus. Faith and Fear’s Most Valuable Met for 2006, when he had a lot of competition. Gold Glove. Silver Slugger. Many-time All-Star. Got what we paid for. And yet, can’t be called THE Met of his time, not when David Wright and Jose Reyes were the marquee attractions at Shea Stadium and Citi Field. Not that Wright and Reyes would have starred on contending clubs without Beltran doing his share alongside them. The marquee between 2005 and 2011 no doubt implied “and featuring…” for Beltran. Definitely played a huge role in his his era, never quite the defining character of his era. That’s not a knock. It’s relevant only to the notion of the Mets rarely being unquestionably led by their center fielder, whoever their center fielder has been. If it didn’t happen when Carlos Beltran was their center fielder, maybe it’s not fair to expect it to have happened ever.

But it did happen on other teams in the prime of Mays and Mantle and DiMaggio and Trout and Griffey and Dale Murphy, to name a handful of immortals; we’ll omit Pete Crow-Armstrong for the sake of our sanity. It’s not like those center fielders are garden-variety, so perhaps the bar is raised too high. If the Mets could be getting Carlos Beltran-level production in center field today, boy would we take it. We’d take the best of Angel Pagan, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer); or the best of Juan Lagares, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer, too); or the best of Brandon Nimmo (who delivered it in center in more years than one, but age shifted him to left). In 2024, we got by with Tyrone Taylor and Harrison Bader, two guys who surely had their ups and downs hitting but caught what needed to be caught, and you almost didn’t notice that they didn’t necessarily hit what needed to be hit. This year, with a powerful enough cast to theoretically excuse a hole in the bottom of the lineup, the top of the lineup has become too hollow to excuse anything.

Center fielder Tyrone Taylor, meet center fielder Cedric Mullins. Neither of you has to be Willie Mays from when he was really the Say Hey Kid. Two or three months making like vintage Mookstra would suffice.

Here’s another one for your collection:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAPwJ8V4geI&list=RDxAPwJ8V4geI&start_radio=1

Win or lose, my day is made.