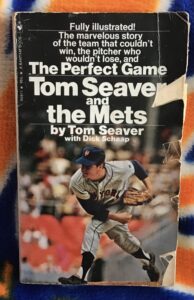

Some Met folklore a fan accepts without wondering about beyond what he’s already picked up. A bit of Metsiana that’s been with me for more than fifty years concerns some activity that preceded Game Four of the 1969 World Series. I picked up on it in 1971, a little late, but forgive me, I was only six when it happened. I was eight when I first read The Perfect Game, Tom Seaver’s first autobiography, written with Dick Schaap. On page 46 of my dog-eared paperback edition, Tom/Dick wrote about a pamphlet being handed out outside Shea Stadium on October 15, just as Tom was preparing to pitch. The pamphlet regarded Seaver and his opposition to the Vietnam War, a conflict that had been raging for years by the fall of 1969 and was still going on when I got my hands on the book.

The kicker was that while Seaver counted himself anti-war at a time when the country was torn apart by the issue, he hadn’t sanctioned the pamphlet that was being distributed. More to the point that Wednesday — Moratorium Day across America — he didn’t want to be distracted from his task at hand, not even when so many millions of Americans would be actively protesting America’s involvement in Vietnam. A friend of mine who was attending Brandeis University then, college basketball author Mark Mehler, ranks “marching against war in October ’69 in Boston, with a radio playing Game Four glued to my ear, the Mets on the side of the angels” as one of the highlights of his longtime if intermittent Mets fandom. When he shared his list in 2015, Mark also wished to make clear to me that Seaver hardly proceeded as if he was distracted: “Your boy pitched great that day.”

The kicker was that while Seaver counted himself anti-war at a time when the country was torn apart by the issue, he hadn’t sanctioned the pamphlet that was being distributed. More to the point that Wednesday — Moratorium Day across America — he didn’t want to be distracted from his task at hand, not even when so many millions of Americans would be actively protesting America’s involvement in Vietnam. A friend of mine who was attending Brandeis University then, college basketball author Mark Mehler, ranks “marching against war in October ’69 in Boston, with a radio playing Game Four glued to my ear, the Mets on the side of the angels” as one of the highlights of his longtime if intermittent Mets fandom. When he shared his list in 2015, Mark also wished to make clear to me that Seaver hardly proceeded as if he was distracted: “Your boy pitched great that day.”

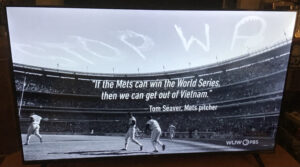

Tom’s ten-inning victory over the Orioles speaks for itself. Moratorium Day’s effectiveness in impacting US policy toward Vietnam is its own topic. I recently found myself watching a 2023 episode of PBS’s documentary series American Experience that delved into those protests a great deal. In the film The Movement and the “Madman,” one clip was devoted to the “STOP WAR” message skywritten over Shea Stadium that very day. Superimposed on the screen was Seaver’s then-provocative quote — “If the Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.” Knowing what I knew, I wasn’t surprised to see it.

But I only knew so much, a few anecdotes here and there, and, of course, a box score reflecting that the Mets were closing in on a world championship. What I never knew — what I don’t think I’d ever seen — were the full contents of that pamphlet that briefly got Tom’s goat in Flushing before he turned his full attention to taming the Birds from Baltimore.

But I only knew so much, a few anecdotes here and there, and, of course, a box score reflecting that the Mets were closing in on a world championship. What I never knew — what I don’t think I’d ever seen — were the full contents of that pamphlet that briefly got Tom’s goat in Flushing before he turned his full attention to taming the Birds from Baltimore.

That’s where A.M. Gittlitz comes in.

A.M. Gittlitz is a writer who contacted me a couple of years ago to tell me he was working on a book called Metropolitans: New York Baseball, Class Struggle, and the People’s Team, which sounded absolutely fascinating to me. A.M.’s publisher, Astra House Press, describes the forthcoming work as “a wide-reaching, revolutionary narrative history of the Team of Destiny that takes us from their 19th century inception to their 1962 resurrection to the present day,” which makes me only more anticipant of its full, multigenerational story. A.M. and I met at the 2023 Queens Baseball Convention, where he picked my brain (such as it is), and have stayed in touch since, occasionally exchanging nuggets that might be of interest to one another. Not long ago, A.M. was kind enough to send along an image of that actual pamphlet, something he’d come across in his voluminous research. My reaction was to be wowed. So that’s what Tom was talking about in The Perfect Game.

A.M. asked me if I’d like him to write something about it for Faith and Fear. Absolutely, I said. Apparently we share an affinity not just for the Mets, but for getting deep into our subject matter, as the article A.M. put together for us deals with far more than the pamphlet, with staggering amounts of backstory, dozens of details that have been lost to time until now, and a blend of perspective and context that feels as relevant in 2025 as it would have in 1969.

I’m delighted he’s bringing it to us here now.

By A.M. Gittlitz

The Summer of Love. Stonewall. The Moon landing. Woodstock. And…the Mets?

In the grand pantheon of 1969’s defining moments, the Miracle Mets’ championship victory seems like it should be a non-sequitur footnote among the decade’s seismic cultural upheavals. Yet this perceived incongruity masks a deeper truth: the Mets were not merely witnesses to the Aquarian Age’s revolutionary currents, but participants, both sculpted by and influential to the era’s most radical transformations.

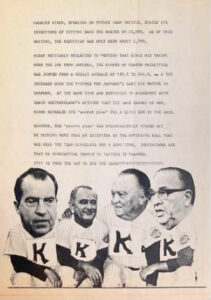

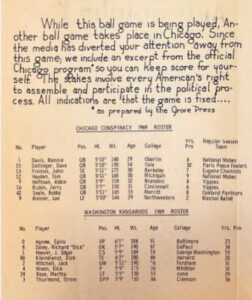

The 1969 pamphlet Mets Fans for Peace — now available online for the first time courtesy of the New York Historical — captures the zenith of the extraordinary convergence between America’s notoriously apolitical pastime and its riotous, Technicolor counterculture.

The playful zine, published by beatnik publishing house Grove Press to be distributed before Game Four of the World Series at Shea, includes screeds against the war in Vietnam, a comparison of the World Series to the “Chicago 8” trial, a call to sing “Give Peace a Chance” after the National Anthem, and even a blank page for autographs. On its cover is the Mets’ starting pitcher that day, Tom Seaver, squinting defiantly as a third-world revolutionary guerrilla in his batting helmet, alongside his recent public declaration that: “If the Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.”

The playful zine, published by beatnik publishing house Grove Press to be distributed before Game Four of the World Series at Shea, includes screeds against the war in Vietnam, a comparison of the World Series to the “Chicago 8” trial, a call to sing “Give Peace a Chance” after the National Anthem, and even a blank page for autographs. On its cover is the Mets’ starting pitcher that day, Tom Seaver, squinting defiantly as a third-world revolutionary guerrilla in his batting helmet, alongside his recent public declaration that: “If the Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.”

Such a public statement from any White athlete was virtually unheard of in baseball then, and sadly now as well. Jackie Robinson had denounced Paul Robeson at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing twenty years prior for making such statements, and US runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos were banned from the Olympics for their “violent” gesture of accepting their ’68 gold and bronze medals with fists raised high for Black liberation. How did the sport Jimmy Breslin described as entering the decade with “all the speed of a Sunday afternoon picnic, and the hipness of a Civil War reenactment,” a sport the commissioner’s office demanded be a “world apart” during the riots of ’68, suddenly find itself in the midst of the action during its championship series?

PROLOGUE TO THE PAMPHLET

The answer goes back to two simultaneous camps of what President Kennedy and Casey Stengel each lovingly dubbed the Youth of America in the spring of 1962.

The first was at United Auto Workers’ retreat in Port Huron, Mich. where a few dozen college kids calling themselves the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) issued a declaration of a second American Revolution that would peacefully end the Cold War, seize the means of production for an autonomous working class, and break spectacular politics in favor of dynamic political communities on local levels.

The second was in St. Petersburg, Fla., where the Mets — a team branded as the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants recombined for a new generation in comic book saturation — held their inaugural Spring Training. In the months and years that followed, the Mets became known as the “people’s team,” an image popularized by beatnik journalists who hyped their unruly, underdog youth fans filling the Polo Grounds with homemade placards, fan clubs, and chants as the “New Breed.” Simultaneously, the ranks of SDS swelled, with their Port Huron statement widely considered the foundational document of the American “New Left”.

New Breed and New Left continued a parallel dance through the decade. The Mets were the offspring of New Deal-era blue-collar Dodger progressivism, with a flashy pop-art aesthetic, beatnik-like rambling manager, and an overmatched young journeyman roster whose players weren’t above hanging out in the coffee houses of West Village bohemia; reliever Ken MacKenzie, nicknamed “Mr. Peepers” for his scholarly thick-rimmed glasses, even moved there. “We’d walk around and see all the art shows, drop in the coffee shops or just watch the people,” the only pitcher to sport a winning record among Original Mets said. “We liked the people down there. Everybody was open-minded. That’s the way we like to operate.”

In 1964, Cleon Jones and Elio Chacon, at that point minor leaguers (Jones on the way up, Chacon trying to hang on) participated in the Civil Rights Movement with a sit-in against a segregated North Florida restaurant. When police arrived, Jones informed them about the recently-passed Civil Rights Act’s ban on racial discrimination for employment and public accommodation. The players were promptly served. When they returned the next night, the waitress again ignored them. Jones invoked Federal Law to management again, and she was fired on the spot. They returned again the next night to find the waitress rehired and apologetic. From then on, Jones wrote in his 2022 memoir, it was their favorite place to eat in Jacksonville.

The same year, much of the New Breed moved on to the New Left by supporting the “Freedom Summer” campaign of registering Black voters in the South. Among them were Mickey Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who moved from Queens to Meridian, Miss., to set up a movement base. In the early summer the two set out with 21-year-old local activist James Chaney to investigate the burning of a Black church nearby. Tailed by sheriffs and Klansmen seeking the “Jewboy with the beard and the bright blue New York Mets baseball cap,” the three were abducted, tortured, and executed.

The violent repression of the Civil Rights Movement, along with the growing scandal of the War in Vietnam, radicalized millions of youth in the years that followed. Thousands left the suburbs and made their way toward urban bohemia, where cheap rent in crowded crash pad communes birthed the Sixties’ culture of public concerts, free meals, and free love. Among them, you might say, was Tom Seaver. The pitching prospect followed in the footsteps of his beatnik older brother, Charles Seaver, who had moved to Greenwich Village at the dawn of the decade and become a sculptor, social worker, and social justice activist. Charles inspired Tom’s taste in rock, folk, and modern literature, as well as his non-conformist path toward his own artistic calling. The pitcher’s mound, Tom said, was “one of the few places left where a person like myself can show his individuality.”

Seaver chiseled 170 strikeouts during his debut 1967 season with a 2.76 ERA, won Rookie of the Year, and established himself at the head of a strong young pitching crop, which included Jerry Koosman, Nolan Ryan, and Tug McGraw, as the cellar-dwelling franchise’s first homegrown star. The Mets, skippered by preternaturally bland Wes Westrum, nevertheless finished last, as they had done almost without fail since 1962.

Tom Seaver was never content with being a “lovable loser” — and neither was much of the New Left. As the Mets’ new manager for 1968, Gil Hodges, went about transforming the residue of Stengel’s Amazins into a competitive team, mass mobilizations, cultural happenings, and riots spread coast to coast demanding peace, equality, and racial justice.

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated on April 4, 1968, shortly before Opening Day, the Mets were among the teams to join what amounted to the first sportwide wildcat strike to honor the civil rights leader’s memory and not play on the day of his funeral, a job action led by Pirates Roberto Clemente and Donn Clendenon, among others. In the wake of Robert F. Kennedy’s June 6 death at the hands of yet another assassin, the Mets, in California, again voted to take another respectful pause from their schedule, especially since the slain presidential candidate had represented New York in the US Senate. This time they were one of few teams to, essentially, stand up for sitting out on the day of RFK’s funeral, June 8.

Commissioner William Eckert demanded the Mets’ pay docked to compensate for the revenue the San Francisco Giants would miss by postponing and having to host a doubleheader to make up the game later in the season (on the same August weekend when the Mets and Giants happened to be also making up the postponed game that coincided with King’s funeral). Hodges sided with his team, and the game was postponed. Kennedy’s press secretary Frank Mankiewicz sent telegrams to the team thanking them for not putting “box office receipts ahead of national mourning”.

By lending his support to the effort, Hodges showed his players that beneath his hardboiled affect, he had their back. The moment of mutual trust served to separate the contemporary Mets from the Westrum-era doldrums, and, coincidence or not, they won eight of twelve games after leaving Candlestick Park. By late June, the Mets had ascended to the middle of the NL standings, flirting with a .500 winning percentage — easily the best position they had ever achieved midseason. The New Breed fans who had drifted away post-Stengel, the pure baseball enthusiasts and the leftists alike, noticed the Mets’ political transformation as well. In July, a group of young Communist Mets fans stormed the offices of the New York Post (not yet under the ownership of Rupert Murdoch) demanding Jimmy Breslin retract a column that criticized the Party. When Post editor James Wechsler confronted the group during its sit-in, he argued their support for a team run by the old-school and conservative Catholic Hodges proved Breslin’s point. “Much to his dismay,” Hodges biographer Mort Zachter wrote, “the Communists strongly defended Hodges.”

Similar politicization emerged in far more radical fashion elsewhere in sports that year, often involving some of the greats of the time. Heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali, a convert to the Nation of Islam, stoically faced jail time for his refusal to be drafted. In October, premier UCLA basketball player Lew Alcindor — who would change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar by the early 1970s — boycotted the Olympics in Mexico City, where the aforementioned runners made their courageous and controversial show of solidarity. While these actions paved the way for other athletes to be more vocal, the baseball diamond saw little equivalence beyond the reactions to the funerals for King and Kennedy. The Black ballplayers who had emerged as both baseball’s top stars and its political vanguard rejected the revolutionary politics and interventionism of the New Left and Black nationalism. Curt Flood, Bob Gibson, Bill White, Willie Mays, and other players had all met with such groups, and came away preferring the Robinson path of interracial struggle in the workplace. “Sounds as if Black power would be White power backwards,” Gibson said. “That wouldn’t be much improvement.”

In the long run, their choice protected baseball’s “world apart” delusion and its taboo on players speaking their mind. But it had also protected the Black ballplayers from scandal, making it easier for them push the radical labor politics of Dr. King in common struggle with their conservative White co-workers, and ultimately turning the Major League Baseball Players Association into one of the strongest unions in the country.

THE SEASON OF THE PAMPHLET

When the MLBPA organized its first strike before the 1969 season, the Mets broke ranks despite GM Johnny Murphy’s promise not to punish the holdouts. Many players viewed their franchise as a uniquely pro-worker “family operation,” lovingly calling owner Joan Payson “Ma Payson” and Murphy “Grandma”. Defying union president Marvin Miller, Seaver and Jerry Grote organized their own spring conditioning camp. Though it took a while for the Mets to climb above .500 to stay in 1969 (47 games), it could be argued the club came together early and benefited as a result. The labor dispute was resolved in favor of the players, and Seaver’s 14-3 launch propelled the Mets to easily their best midseason record yet.

Sensing the franchise’s first winning season was finally at hand, Johnny Murphy traded four prospects to Montreal for slugger Donn Clendenon, the same first baseman who worked with Clemente to honor King. The veteran brought intellectual leadership along with a skilled bat. Clendenon played for the semi-pro Atlanta Black Crackers under Negro League stars and befriended Dr. King at Morehouse College. After twelve frustrating years in the Pittsburgh organization (he wasn’t promoted to the bigs until 1961, the year after Bill Mazeroski lifted the Bucs to a world championship), Clendenon briefly retired rather than play for the Astros, to whom he’d been traded in January by the Expos, who had selected him in the previous October’s expansion draft. Clendenon wanted no part of Houston manager Harry Walker — brother of anti-Robinson hate-strike leader Dixie Walker — but reluctantly returned to baseball amid swirling pressures. Houston’s owner, Roy Hofheinz, threatened to buy Clendenon’s offseason employer, Scripto, the pen company where the in-limbo ballplayer held an executive position, and close off his off-field career option.

The first baseman never did become an Astro, as new commissioner Bowie Kuhn lobbied for resolution among all parties, and Clendenon returned to the Expos for the new season. This might have been better than winding up in Houston, but it seemed to guarantee he’d spend yet another summer going nowhere in the standings, given Montreal was on its way to 110 losses in its first year. The June 15 trade to the second-place Mets, a month before his 34th birthday, suddenly granted him one final shot at October glory.

For the rest of the season, as Seaver, Clendenon and all the Mets chased the frontrunning Cubs, “Shea Stadium took on a carnival-like atmosphere,” in the words of Art Shamsky. There was a proliferation of confetti, banners, and fireworks rivaling the Central Park be-ins and free rock festivals. It was the new Haight-Ashbury or St. Mark’s Place, the latest cosmic center of the Sixties. Messianic signs, afros, and puffs of marijuana smoke dotted the stands, with dropouts outside loitering like Deadheads begging for a free-ticket miracle. Even as the Mets cooled off in July, their broadcasts became the de facto soundtrack of taxi rides, delis, and bars. “No one had seen that kind of midsummer fever in the city since the old Giants-Dodgers bloodlettings, fifteen or twenty years back,” Roger Angell wrote. The New York Times weighed the return of Metsomania against the Apollo 11 moon mission: “A bartender was asked whether his customers were more interested in the Mets or the astronauts. ‘The Mets, of course,’ he said. ‘Aren’t you?’”

They were revolutionary stand-ins for some and a helpful topic of conversation for those attempting to reach beyond the leftist subculture to working-class squares for others. “Politics should be as exciting as the New York Mets,” Yippie founder Jerry Rubin wrote in his 1969 manifesto Do It!. “People are always asking us, ‘What’s your program?’ I hand them a Mets scorecard.”

For The Man, however, they were a distracting tool of neutralization. After two summers of rage so arsonous that the political class, from City Hall to the Pentagon, had been drawing up plans for widespread counterinsurgency, the summer of ’69 unfolded as an unlikely optimistic benchmark of the ending decade. There were race riots in York, Pa.; tenant riots against evictions in Harlem; and the weekend-long queer riot outside the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village — but some within the establishment credited the Mets with the failure for these revolts to spread as they had in previous years. “We calmed that damn town down,” pitcher Gary Gentry claimed. “I remember getting all the ‘attaboys’ and ‘thank yous’ from our city and state officials, as well as Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Mayor John Lindsay. You know, I don’t think we knew what we were doing when we were doing it, but after it was over, I heard a lot about how we turned the town around.”

As the Mets continued their underdog surge, many revolutionaries found The Movement terminally devolving into a performative blame game among a proliferation of bizarre teams. That summer’s SDS convention at the Chicago Coliseum took on the doomed atmosphere of Wrigley Field’s home clubhouse, its ’62 New Left treatise now decisively lost in a snakepit of factional polemics. The SDS died at the convention’s end, in a volley of rival Stalinists chanting “Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh!” and “Mao! Mao! Mao Tse-tung!” at one another. The last SDSers left in disgust during the shouting match, with one New York Trotskyist cadre, the Larouchites, answering them: “Let’s! Let’s! Let’s Go Mets!”

The height of Shea’s frenzy arrived with the return of the Cubs in the second week of September. Their nine-and-a-half game lead over New York — which started to shrink on August 15 as Chicago lost at San Francisco, in harmonic convergence with the beginning of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, an event that drew more than 400,000 peace & love pilgrims to Max Yasgur’s farm, 84 miles north of Flushing (where the regional rains that postponed a Friday night Mets-Padres game didn’t stop the mud in Bethel from growing legendary) — now whittled to two-and-a-half. The stadium swelled far past capacity, thanks to thousands of fans cashing in free tickets handed out as a promotion for Borden Milk before the season. In the top of the first, on-deck hitter Ron Santo noticed the massive energy in the crowd, even louder than it had been in July. “‘Oh man, we’re fucked now,’” Cubs batboy Jim Flood recalled him saying. “And that’s when I saw the cat.”

Legend had it that dozens of Flushing’s feral felines had made Shea’s netherworld their home since 1964, giving the locker rooms, late-’70s reliever Skip Lockwood recalled, the “musty smell of a summer cottage”. Perhaps the noise had roused the feline from its lair, or perhaps he had been smuggled in and set loose as a Yippie or Stengelian prank. Either way, the black cat, an archetypal symbol of black magic and proletarian sabotage, now ran free through foul territory, fearlessly crossing Santo toward the dugout to glare directly at the Cubs’ crashing manager. “Somebody get that fucking cat out of here!” Leo Durocher yelled. Then, as if the symbolism had not been obvious enough, “the frightened feline,” Richard Dozer reported in the Chicago Tribune, “reversed his course and dashed under the stands to safety on the other side, next to the Mets’ dugout.”

“The whole thing was bizarre!” Shamsky exclaimed in print more than a half-a-century later.

The Mets’ divisional clinch on September 24 unleashed unprecedented mayhem at Shea. Future broadcaster Howie Rose and friends abandoned their Upper Deck seats, planning to storm the field, only to discover every aisle packed with kids harboring identical schemes. When the Cardinals’ Joe Torre grounded into a double play to put the franchise’s thus far greatest victory in the books, Rose, 15, charged onto the field with approximately 20,000 other fans in a spontaneous celebration that overwhelmed some 300 helpless policemen. Leonard Koppett captured the moment’s primal energy: “They poured out of the stands like deranged lemmings, like the mob attacking the Bastille, like barbarians scaling the walls of ancient Rome.” Links of fence, seat slats, and even the American flag became trophies. Later that night, about 100 fans returned chanting, “Shea belongs to the people!”

The Mets proceeded to the very first National League Championship Series against the Atlanta Braves. Hank Aaron was characteristically remarkable in Game One, homering off Seaver to put the Braves up, 5-4, in seventh. The Mets answered back in the eighth with a five-run rally that won the game and steered New York toward a series sweep. Per the description of an Associated Press reporter, when the pennant was decided in Queens, “a mini ‘Woodstock Pop Festival’ set in on the infield.”

“[N]othing was going to stop them,” Aaron wrote in his 1991 memoir. “One of my teammates, Tony Gonzalez, said that we ought to send the Mets to Vietnam and let them win the war.” It’s possible Cuban ex-pat Gonzalez made this remark knowing some on the Mets did want the war to end, as the rest of the country soon found out. “I think it’s perfectly ridiculous what we’re doing about the Vietnam situation,” Tom Seaver told United Press International the day before starting Game One of the World Series. “If the Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.” The Times republished the story the next day under the headline, “Tom Seaver Says U.S. Should Leave Vietnam”.

Seaver’s statement was suggested by the Moratorium Day Committee, a left-liberal coalition planning a mass and mainstream nationwide march against the war on October 15, supported by “heartland” institutions like churches and small businesses, along with moderate politicians. Some in the coalition were radicals disturbed by the growing backlash against the Yippie and Black Panther-dominated countercultural protests of previous years, including the protest’s New York organizer, Charles Seaver.

While the Seaver brothers may not have been fully politically aligned, the two agreed the war had to end — a possibility that once seemed about as likely as the Seaver’s start in Game Four of the World Series the same day. Outside of New York, consensus suggested that the Mets stood no chance of actually winning the World Series. “[A] meeting of the Incomparables against the Improbables,” is how Joe Trimble previewed it for Daily News readers the day before the Amazin’ Mets took on the big, bad Birds. Sportswriters nationwide considered the 100-win Mets’ 109-win Baltimore Oriole opponents the best team since the mythic ’61 Yankees, and the AL champs’ star outfielder Frank Robinson charitably predicted the best-of-seven series would last only five. Oddsmakers in Las Vegas installed the O’s as 8-5 favorites…though that was the same bunch that decided at the season’s outset that the 1969 Mets were 100-1 underdogs to win their pennant.

After the Mets lost the first game in Baltimore, 4-1, Clendenon, one of the few veterans on the youngest team in baseball, called a players-only meeting. “Gentlemen, trust me,” he announced. “We are going to kick their asses for the rest of the series.” He had seen in the sparse and dispassionate crowd at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium that afternoon what their otherwise powerful opponents lacked — something akin to the Beach Boys’ “good vibrations” or Jim Morrison’s Mojo, a confidence that everything will supernaturally go your way. All summer long, umpire calls, bounces, weather, and nearly every other chance element of the game seemed to carom in the Mets’ favor, leading Seaver to declare in a fit of Aquarian mysticism that “God lives in New York.” Or at least, as he answered NBC analyst Sandy Koufax when the lefty pitching deity asked him whether God was in fact a Met, “No, but He’s got an apartment” in town.

Rationalist Clendenon asserted a less mystical path to victory. Since his acquisition and the early-July Cubs series that put the 1969 Mets on the contending map, the people of New York and their team had worked as a singular unit at Shea. Their volume and energy inspired the team to put more balls in play, where what looked like “lucky breaks” were often the bobbles or missed calls of intimidated umpires and thrown-off opponents. If the Mets could win the next game in Baltimore, Clendenon promised, they could use that home field advantage to win it all in New York.

With battle plans drawn, the Mets’ amorphous and egalitarian platoons unleashed their ambush. They narrowly took Game Two, 2-1 on a ninth-inning single by light-hitting Al Weis. Two days later at Shea, Agee led off Game Three with a home run against future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer, and would go on to save five runs via a pair of daring outfield catches. Winning, 5-0, the Mets took the lead in their asymmetric war. “You know what somebody told me?” bullpen coach Joe Pignatano asked rhetorically afterwards. “God is a Met fan.”

Then came Game Four and Moratorium Day. Reliever Tug McGraw arrived to the ballpark to find a young cadre fanned out around Shea distributing literature and holding signs. One read: BOMB THE ORIOLES — NOT THE PEASANTS!

He strolled over and grabbed their pamphlet titled METS FANS for PEACE. McGraw proceeded to the clubhouse and handed it to the ace with a smile. “You really say this?”

But Seaver, already on edge ahead of his start, took a glance at the pamphlet and threw it out. Its return address revealed it had not originated from his brother’s respectable Moratorium Day committee, but the far more radical “Chicago Conspiracy” — the defendants, including Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and Black Panther Bobby Seale, charged with orchestrating the riots that overwhelmed the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. “There’s NO way to know exactly who did this handiwork,” Sixties countercultural historian Pat Thomas told me, “but it’s certainly a Yippie-type thing. And the fact that there’s an address for the Chicago 8 defense fund […] means that’s truly connected to Jerry or Abbie in some fashion!”

But Seaver, already on edge ahead of his start, took a glance at the pamphlet and threw it out. Its return address revealed it had not originated from his brother’s respectable Moratorium Day committee, but the far more radical “Chicago Conspiracy” — the defendants, including Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and Black Panther Bobby Seale, charged with orchestrating the riots that overwhelmed the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. “There’s NO way to know exactly who did this handiwork,” Sixties countercultural historian Pat Thomas told me, “but it’s certainly a Yippie-type thing. And the fact that there’s an address for the Chicago 8 defense fund […] means that’s truly connected to Jerry or Abbie in some fashion!”

Feeling himself the latest victim of the Yippies’ notorious pranks, Seaver regretted ever having made his comment about Vietnam. While Seaver did end up buying a small ad in the New Years’ Eve edition of the Times requesting a “prayer for peace” (“can’t argue with that,” Ron Swoboda reasoned in his 2019 memoir), he rarely talked publicly about politics again.

Anti-war Mayor Lindsay — who was attempting to ride the Mets’ coattails in what appeared to be a long shot re-election bid — also got cold feet before the game. He had ordered all flags on city buildings, including Shea, flown at half-mast in recognition of Moratorium Day’s mission. In response, the US Merchant Marine Academy band and war-wounded veterans scheduled to take the field for the anthem said they would boycott. When the police indicated they might strike as well, Kuhn called Lindsay. Worried an unprotected Shea could become the next Woodstock, Seaver took the field for “The Star-Spangled Banner” with the flag flying high, and a noticeable number of fans defiantly seated.

Seaver went on to pitch all ten innings of the 2-1 win, a game best remembered for Swoboda’s improbable robbery of Brooks Robinson in right field and J.C. Martin’s conveniently placed wrist creating the Oriole error that led to the winning run (along with Clendenon blasting the second of his MVP-earning three homers). A statement by the Chicago Conspiracy published in the East Village Other, the New York counterculture’s paper of record, hailed the victory: “TOM SEAVER: WE WANT YOU TO KNOW OF OUR CONTINUED SUPPORT OF THE N.Y. METS IN THEIR BATTLE WITH THE AGGRESSORS FROM THE AMERIKAN LEAGUE … POWER TO THE N.Y. METS!

Seaver went on to pitch all ten innings of the 2-1 win, a game best remembered for Swoboda’s improbable robbery of Brooks Robinson in right field and J.C. Martin’s conveniently placed wrist creating the Oriole error that led to the winning run (along with Clendenon blasting the second of his MVP-earning three homers). A statement by the Chicago Conspiracy published in the East Village Other, the New York counterculture’s paper of record, hailed the victory: “TOM SEAVER: WE WANT YOU TO KNOW OF OUR CONTINUED SUPPORT OF THE N.Y. METS IN THEIR BATTLE WITH THE AGGRESSORS FROM THE AMERIKAN LEAGUE … POWER TO THE N.Y. METS!

The world championship miracle was completed at Shea the next afternoon. A few days later, a million filled the Canyon of Heroes waving orange pennants and cheering the Mets as they had the returned moonwalkers two months prior. “It was like V-J Day in New York,” author Bill Ryczek wrote decades later. “Confetti rained down from office windows. Strangers hugged each other on the street. Church bells rang […] The Yankees had won twenty World Series titles, but not once had they been given a ticker-tape parade,” certainly none directly on the heels of a Fall Classic victory.

EPILOGUE TO THE PAMPHLET

The 1969 Mets had done all they could do to inspire or perhaps distract their metropolis. “If the Mets, with their reputation as beloved fools, could win a World Series in only their eighth season,” George Vecsey posited, “why anything could happen — the Vietnam War could end; cancer could be cured; the races could learn to live together; poverty could be erased. Anything.” Vecsey, however, wrote that for Inside Sports in 1979, knowing full well that for all the 1969 Mets could do, they could do only so much.

The Vietnam War would expand and drag on. American troops weren’t withdrawn until early 1973, and the overall conflict didn’t end for more than two years beyond that. During the 1970s, the left continued to fracture, and New York City and its Mets each crumbled under the respective austerity regimes of the state’s Emergency Financial Control Board (NYC) and stock trader M. Donald Grant (NYM). In 1979, six years after McGraw convinced Shea skeptics that “You Gotta Believe!” and two years after Grant demolished belief by dispatching Seaver to Cincinnati, the rapidly aging municipal stadium couldn’t have presented a bleaker tableau, as the Mets failed to draw 800,000 fans and lost nearly 100 games. Still, the place sparked to joy one Saturday afternoon in July when a majority of the 1969 Mets reunited to toast their tenth anniversary, reminding anybody who maintained emotional investment in the franchise that better days were possible.

In 1980, new owners Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon branded their distressed property, one that cost them a then-record $21.1 million to take over from Mrs. Payson’s heirs, the People’s Team; the phrase was emblazoned on the cover of the official yearbook. While this iteration of the Amazins had a ways to go competitively, management made what it could of the residual goodwill that lingered from the Metsies’ initial glory days. When an ad campaign promised “The Magic is Back,” it referred not to on-field exploits but the emotions National League baseball in New York once upon a time evoked. Sure enough, strands of the Metsian spirit that first saw light in ’62 and illuminated the city in ’69 have made themselves visible intermittently ever since. Witness the party-punk attitude of the ‘86 championship team; the Mojo Risin’ rallying cry of 1999; the black-clad run to the 2000 Subway Series; and the unifying scenes of the Mets’ game against the rival Braves on September 21, 2001, serving as New York’s first mass gathering after the World Trade Center attacks. Attitudinally, the Mets’ vibes-infused romp to and within the 2024 playoffs at Citi Field echoed the sounds of the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium at their most raucous.

In 1980, new owners Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon branded their distressed property, one that cost them a then-record $21.1 million to take over from Mrs. Payson’s heirs, the People’s Team; the phrase was emblazoned on the cover of the official yearbook. While this iteration of the Amazins had a ways to go competitively, management made what it could of the residual goodwill that lingered from the Metsies’ initial glory days. When an ad campaign promised “The Magic is Back,” it referred not to on-field exploits but the emotions National League baseball in New York once upon a time evoked. Sure enough, strands of the Metsian spirit that first saw light in ’62 and illuminated the city in ’69 have made themselves visible intermittently ever since. Witness the party-punk attitude of the ‘86 championship team; the Mojo Risin’ rallying cry of 1999; the black-clad run to the 2000 Subway Series; and the unifying scenes of the Mets’ game against the rival Braves on September 21, 2001, serving as New York’s first mass gathering after the World Trade Center attacks. Attitudinally, the Mets’ vibes-infused romp to and within the 2024 playoffs at Citi Field echoed the sounds of the Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium at their most raucous.

Substantively, the larger Met story has diverged from the one that could be told convincingly at the end of the Sixties. For example, in a tacit turn toward post-9/11 jingoism, the Mets’ organization effectively (and I’d say sadly) disavowed any remnants of their anti-war past. Their institutionalization of the seventh-inning ritual singalong of “God Bless America” — processed widely as a pro-war song since World War I — remained a staple of the game-going experience long after the initially popular War on Terror descended into a torturous quagmire. It wasn’t just the Mets, of course. Most every team embraced Irving Berlin’s composition well past the prevailing mood of overwhelming sadness and patriotic fervor that informed the final weeks of the 2001 season, whether it continued to be played daily or was performed weekly.

One high-profile player, however, then wearing the uniform of MLB’s only non-US team, resisted taking part. He chose instead to remain in the dugout during the playing of the song, as the US conducted military operations not just in Afghanistan (which were a direct response to the terrorist attacks that stunned New York), but, as of March 2003, in Iraq.

“I don’t [stand] because I don’t believe it’s right,” outspoken Puerto Rican slugger Carlos Delgado, then with the Toronto Blue Jays, explained in 2004, a year when he was booed at Yankee Stadium for his stance. “I don’t believe in the war. […] I think it’s the stupidest war ever. […] We have more people dead now, after the war, than during the war. You’ve been looking for weapons of mass destruction. Where are they at?”

After Delgado was traded from the Florida Marlins to the Mets in advance of the 2006 season, management, prioritizing a show of solid support for US troops overseas, mandated their new first baseman stand with the rest of his teammates for the now entrenched Sunday singing, and Delgado complied, wishing to “not put myself in front of the team. The Mets have a policy that everybody should stand for ‘God Bless America,’ and I will be there. I will not cause any distractions to the ballclub.” Delgado wound up contributing 38 home runs and 114 runs batted in to a division-winner, and as long as he kept hitting, his association with not standing for a ritual he didn’t care for faded as a hot-button talk radio issue.

A touch of New Left/New Breed energy returned to the Met sphere during the veritable “bubble season” of 2020, the year when, in deference to the COVID-19 pandemic, only cardboard cutouts attended baseball games. After the late-August police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, in Kenosha, Wisc., a wildcat strike spread throughout the NBA and permeated MLB. The Mets’ lone prominent African-American player, Dom Smith, took a knee during the national anthem on August 26 — following former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s preferred mode of racial injustice protest from 2016 — while his teammates all stood. “I think the most difficult part is to see people still don’t care,” Smith said through postgame tears that night. “For this to just continuously happen, it just shows the hate in people’s heart…and that just sucks, you know? Black men in America, it’s not easy…”

The next day, Smith helped organize a choreographed walkout of the Mets’ home game versus the Marlins, with the visitors to Citi Field fully on board. New York outfielder Michael Conforto and Miami shortstop Miguel Rojas, the ballclubs’, respective player representatives, collaborated on the details. The evening of August 27 was laced with symbolism that included a 42-second moment of silence intended to invoke the impact of Jackie Robinson, and a Black Lives Matter shirt left on home plate, a gesture intended to make a meaningful statement inside an empty ballpark.

Like Seaver’s speaking out against the Vietnam War more than five decades earlier, Smith’s actions came in the context of a reasonably popular mass movement — the protests that rose in response to the death of another Black man, George Floyd, at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. It can be inferred that the players of the modern era will be far more likely to speak their mind regarding contemporary issues, which today include genocidal war and saber-rattling overseas, and the horrifying repression of migrant workers, women, queers, and dissidents at home, if they feel they are in step with mass movements and therefore shielded from standing (or kneeling) all alone. Another politicized moment of Mets greatness on the scale of ‘69, then, may be up to us — we the fans who stand up for our principles as we see necessary. The stories of Delgado and Kaepernick, each of whom courted levels of ostracization for going against the established grain in this century’s first quarter, indicate how dangerous it can be for an athlete to speak out otherwise.

I am not yet all the way through, but thank you Greg, and A.M. Gittlitz for making this available. It is fascinating!

Something not mentioned (that I saw) is that Seaver was a member of the Marine Reserves in 1969. In “The Perfect Game” he credits his training (along with other physical work) with giving him a frame/musculature/mindset to become a big time pitcher.

I was 6/7 in 1969 so I don’t have personal memories of this but from what I’ve read/seen it was something of a taboo for a member of the Armed Services to take that sort of stance.

Interesting stuff. Thank you.

Carlos Delgado embarrassed himself with his ignorant protest of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Regarding Delgado’s “You’ve been looking for weapons of mass destruction. Where are they at?”, first of all, per UNSCR 1441, Iraq was obligated to prove it disarmed its WMD in accordance with UNSCR 687. The US and UN, enforcing UNSCRs 687 and 1441 pursuant to UNSCR 678, were not obligated to find Iraq’s WMD. Nevertheless, the UNSCR 1441 inspections’ UNMOVIC Clusters document which principally triggered OIF, the ex post investigation’s Iraq Survey Group report, and Operation Avarice, the CIA’s separate WMD munitions confiscation program, are packed with UNSCR 687 WMD violations that confirm Iraq did not disarm per UNSCR 687 with “about 100 unresolved disarmament issues” (UNMOVIC) in Iraq’s “final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations” (UNSCR 1441), Iraq never intended to disarm as “the Iraqis never intended to meet the spirit of the UNSC’s resolutions” (ISG), and Iraq did in fact possess an active WMD program in violation of UNSCR 687. To wit, ISG director David Kay: “In my judgment, based on the work that has been done to this point of the Iraq Survey Group, and in fact, that I reported to you in October, Iraq was in clear violation of the terms of [U.N.] Resolution 1441. Resolution 1441 required that Iraq report all of its activities — one last chance to come clean about what it had. We have discovered hundreds of cases, based on both documents, physical evidence and the testimony of Iraqis, of activities that were prohibited under the initial U.N. Resolution 687 and that should have been reported under 1441, with Iraqi testimony that not only did they not tell the U.N. about this, they were instructed not to do it and they hid material.”

Delgado was also ignorant about “We have more people dead now, after the war, than during the war.” The reason for that is the Saddam regime was a world-leading terrorist organization with “considerable operational overlap” (IPP) with the al Qaeda network among Saddam’s “regional and global terrorism, including a variety of revolutionary, liberation, nationalist, and Islamic terrorist organizations” (IPP). Note, Saddam’s UNSCR 687 terrorism violation was a primary casus belli along with Iraq’s UNSCR 687 disarmament violation and UNSCR 688 human rights violation. Saddam held back his terrorist capability versus the OIF invasion which faced Iraq’s outmatched conventional military. Saddam’s terrorist army was deployed as a guerilla insurgency versus the OIF reconstruction and stabilization operations. To be fair to Delgado, he was not alone in his ignorance about Saddam’s terrorism that was behind the higher post-war Iraqi and coalition casualties. In 2004, coalition leaders were ignorant about the full extent of the Saddamist terrorist threat, too, and caught off guard because US and UK counterterrorism officials had highly underestimated Saddam’s terrorism. It wasn’t until the Iraqi Perspectives Project reported its findings in 2007 did we learn of the world-leading extent of Saddam’s terrorism that constituted the insurgency, and which was also behind the increase of the al Qaeda threat. To wit, IPP found that Saddam and bin Laden’s respective “terror cartel[s]” “increased the aggregate terror threat” by “seeking and developing supporters from the same demographic pool”.

Regarding Greg’s “the US conducted military operations not just in Afghanistan (which were a direct response to the terrorist attacks that stunned New York), but, as of March 2003, in Iraq,” it should be noted that Public Law 107-40, the 9/11 mandate for Operation Enduring Freedom, in fact had two parts. The first 9/11 mandate covered OEF’s “direct response to the terrorist attacks”. The second 9/11 mandate was to “deter and prevent acts of international terrorism against the United States” (Public Law 107-40), which covered Saddam’s terrorism. The second 9/11 mandate was redundant when it came to Iraq since the older standing mandate to “bring Iraq into compliance with its international obligations” (Public Law 105-235) pursuant to UNSCR 678 already covered Saddam’s terrorism per paragraph 32 of UNSCR 687. To wit, IPP co-author Jim Lacey: “… All of this is just the tip of the iceberg of available evidence demonstrating that Saddam posed a dangerous [terrorism and WMD] threat to America. There are other reports providing specific information on dozens of terrorist attacks, as well as details of how Iraq helped plan and execute many of them. Moreover, there is also proof of Saddam’s support of Islamic groups that were part of the al-Qaeda network. … 9/11 camouflaged the terror threat posed by Saddam. In reality Saddam and bin Laden were operating parallel terror networks aimed at the United States. Bin Laden just has the distinction of having made the first horrendous attack. Given the evidence, it appears that we removed Saddam’s regime not a moment too soon.”

Carlos Delgado’s public protest of Operation Iraqi Freedom is a cautionary tale of a celebrity putting foot in mouth over an issue he was painfully ignorant about. Hopefully since 2004, Delgado has taken it upon himself to learn the law and facts that define OIF’s justification.

My buddy sent me this email regarding that magical time in Mets’ history {1969) very well written I enjoyed reading it

The real reason why the WMD’s have not been found to this day is not all that layering of information about how Saddam was the bad guy and UN (LOL!) resolution this and resolution that, rather it’s that you can’t prove a negative so the narrative remains as is in perpetuity. Where’s Scott Ritter? Maybe he can chime in.

Greg G,

Scott Ritter was not an UNMOVIC inspector in 2002-2003, and the 06MAR03 UNMOVIC Clusters document speaks for itself. Ritter is most notable for his March 2000 testimony to Congress as a former UNSCOM inspector that informed Congress’s view that Iraq was likely hiding nuclear weapon capability.

Actually, UNMOVIC, the Iraq Survey Group, and Operation Avarice’s findings positively confirm that at Iraq’s “final opportunity to comply” (UNSCR 1441), Iraq did not disarm its WMD as required by UNSCR 687 for casus belli, and did possess WMD items and activities in violation of UNSCR 687.

To clarify the operative role of “UN (LOL!) resolution this and resolution that”, under the US law and policy that enforced the UNSCR 660 series since 1990-1991, Saddam’s “bad guy” threat was diagnosed and resolved according to Iraq’s compliance with the UN-mandated Gulf War ceasefire terms, which were purpose-designed to resolve Iraq’s Gulf War-established manifold threat, including terrorism, WMD, and human rights abuses. Within the Gulf War ceasefire “governing standard of Iraqi compliance” (UNSCR 1441), UNSCR 687 and related resolutions defined the operative Iraq WMD issue. Iraq’s measurable noncompliance with the Gulf War ceasefire terms evaluated Iraq’s threat, and Iraq’s noncompliance at Iraq’s “final opportunity to comply” (UNSCR 1441) is confirmed. ISG confirmed the Saddam regime never intended to comply with the UN mandates required to resolve Iraq’s threat.

The Iraq Survey Group and Operation Avarice found plenty of WMD evidence after the invasion, and it’s remarkable that so much WMD evidence was found given the systematic denial of evidence by Iraqi counterintelligence. Regarding the WMD evidence that “have not been found to this day”, the ISG report makes clear that what was not found is mainly due to Iraq’s “denial and deception operations” (ISG), including “the unparalleled looting and destruction, a lot of which was directly intentional, designed by the security services to cover the tracks of the Iraq WMD program and their other programs as well” (David Kay). Keep in mind that Iraq’s denial of evidence to the UNSCR 678 enforcers was in and of itself a ceasefire violation for casus belli.

Disiregardless of the legal technicalities that serve as a cover for my aforementioned point, the war was really sold in the media and not in the courts. Again this was based on the inability to prove something that doesn’t exist. We could go on and on, but that’s the reality of the situation. Not many (if any) that voted on the war in Congress followed along or were even aware of all the legalities to which you expertly point out. To clarify – this war was sold by the NeoCons. At the end of the day it was a noble endeavor to establish another solid democracy in the Middle East, but the people of these Unites States of America were sold a bill of goods. Plan and simple. To provide perfect clarity.

GGreen23,

To clarify, the Iraqi democratic reform policy was a UNSCR 688 enforcement measure that was initiated by the HW Bush administration, developed and carried forward by the Clinton administration, and codified by Congress in 1998.

“Not many (if any) that voted on the war in Congress followed along or were even aware of all the legalities to which you expertly point out” is a self-contradictory statement since Congress by definition created the US laws in the “legalities” that mandated the President to “bring Iraq into compliance with its international obligations” (Public Law 105-235), “enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq” (Public Law 107-243), and “ensure that Iraq abandons its strategy of delay, evasion and noncompliance and promptly and strictly complies with all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq” (Public Law 107-243) with “the use of all necessary means to achieve the goals of Security Council Resolution 687 [and 688]” (Public Law 102-190).

Of note, the Congressional law on Iraq prioritized that the President resolve the Saddam regime’s terrorism per UNSCR 687 and human rights abuses per UNSCR 688 along with WMD disarmament per UNSCR 687.

Do you really believe that Congress was not aware and did not follow along its own laws on Iraq that Congress reiterated from 1991 to 2002 mandating the President “to use United States Armed Forces pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 678” (Public Law 102-1)?

As for Iraq’s UNSCR 687 WMD violation, how do you get “this was based on the inability to prove something that doesn’t exist” from UNMOVIC finding that “UNSCOM considered that the evidence was insufficient to support Iraq’s statements on the quantity of anthrax destroyed and where or when it was destroyed…With respect to stockpiles of bulk agent stated to have been destroyed, there is evidence to suggest that these was [sic] not destroyed as declared by Iraq” and the Iraq Survey Group finding that “Resolution 1441 required that Iraq report all of its activities — one last chance to come clean about what it had. We have discovered hundreds of cases, based on both documents, physical evidence and the testimony of Iraqis, of activities that were prohibited under the initial U.N. Resolution 687 and that should have been reported under 1441, with Iraqi testimony that not only did they not tell the U.N. about this, they were instructed not to do it and they hid material” (David Kay)?

Like I said, the Iraq Survey Group was able to find plenty of WMD evidence in spite of the systematic denial of evidence by Iraqi counterintelligence “concealment and destruction efforts” (ISG). For example, ISG found “the Iraqi Intelligence Service (IIS) maintained throughout 1991 to 2003 a set of undeclared covert laboratories to research and test various chemicals and poisons…The network of laboratories could have provided an ideal, compartmented platform from which to continue CW [chemical weapons]” and “From 1999 until he was deposed in April 2003, Saddam’s conventional weapons and WMD-related procurement programs steadily grew in scale, variety, and efficiency…Prohibited goods and weapons were being shipped into Iraq with virtually no problem” (Iraq Survey Group).

GGreen23,

Add regarding “Not many (if any) that voted on the war in Congress followed along or were even aware of all the legalities to which you expertly point out”, the US laws I cited in my August 21, 2025 at 10:25 PM reply, ie, Public Laws 102-1, 102-190, 105-235, 107-243 of course, as well as PL 105-338 (the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998), were each prominently cited in the 2002 authorization, PL 107-243, to define the use of force with Iraq. So far from not following along or being unaware of them, the “many…that voted on the war in Congress” literally voted (again) for “all the legalities” I pointed out.