The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 28 April 2020 4:56 pm 1976 was the first year I collected baseball cards.

I’d peruse rack packs — three blisters of cards, the top and bottom player in each blister visible through the plastic — at the local stationery store or McCrory’s at the Smith Haven Mall. I was searching for the maize-and-blue banners that, at least in 1976, denoted the New York Mets. Such searches were often frustrating and sometimes futile. I remember dissolving into tears the night my best friend’s brother somehow pulled a Tom Seaver from his first rack pack and a Mets team card from his second, while I was flipping through yet more Don Hoods and Nyls Nymans and OH BOY YET ANOTHER MIKE ANDERSON TRADED CARD. Then Robert wouldn’t trade me either of those Mets cards. Not for that near-perfect ’76 Johnny Bench I’d found, and in fact not for my entire stack.

The fronts of those ’76 cards were the main attraction, but I soon figured out that the real treasures were on the backs. That’s where my baseball education began. First came the agate type of career stats, which revealed that the current crop of Mets had pasts, some of which were long and complicated. Jesus Alou and Rusty Staub had been playing baseball since 1963, an impossibly long time ago, and they hadn’t always played for the Mets. Alou had been a member of the Giants, the Astros and the A’s, while Staub had played for an outfit called the Colt .45’s, who no longer seemed to exist. And Ed Kranepool had been around even longer than that — he’d been a Met in 1962, which I already knew was the first year there was such a thing as a Met.

That meant Ed Kranepool’s little cardboard rectangle somehow encompassed the entire history of the Mets. That was a mind-blowing idea for a seven-year-old, and one that encouraged further exploration — even if it also created some unrealistic expectations. Kranepool had hit 14 homers and hit .280 in 1971; surely he’d figure out how to do that again. Tom Hall had been around for a long time and had a 3.21 career ERA, which I’d learned was good. Why wasn’t he talked about all the time, now that he was a Met? Skip Lockwood had posted a 1.56 ERA, and not a million years ago but in 1975, and as a Met. Why hadn’t I known this? Lockwood was a superstar, but no one seemed to mention it.

Herein lies a story. Many stories. The flip side of that idea was that some guys I knew were part of the Mets pantheon didn’t seem to be all that good, at least not when measured by the backs of their baseball cards. Six ’69 Mets remained Mets in good standing in the ’76 card set. The statistical merits of Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman were obvious, even to a young newcomer. But the cardbacks of Kranepool and Wayne Garrett and Bud Harrelson suggested they were rather pedestrian players, which I knew couldn’t be true because they were Miracle Mets. There was a puzzle here, one I had to figure out.

And there was evidence that baseball was far bigger than I’d guessed. Take the back of Craig Swan‘s card. It showed a baffling progression of career stops: Memphis, Tidewater, Mets, Tidewater, Mets, Tidewater, Mets. What was Tidewater, and why did Swan keep returning there? Mike Vail‘s card was even stranger, beginning with something called the Sar. Cards and moving on to Modesto, Ced. Rap. and Arkansas. What could “Ced. Rap.” possibly mean?

And, as if that weren’t enough, some cards talked about other players and places and impossibly long-ago years. The backs of ’76 Mets cards taught me that Christy Mathewson had hurled (great word, that) three shutouts in the 1905 World Series, that Joe Sewell had fanned only four times in 608 at-bats in 1925, and that Connie Mack had been manager of the Philadelphia A’s for 50 years. That last one came complete with a little cartoon showing a man in civilian clothes. Connie Mack? Philadelphia A’s? There was so much I didn’t know, but it wasn’t intimidating when taken one cardboard slice at a time. It was intoxicating.

I quit collecting baseball cards in ’81, then returned to it a few years later, essentially by accident. That kicked off a slow-motion, decades-long landslide: collecting all the Topps Mets cards; collecting all the Mets cards from any manufacturer; collecting all the Topps cards for players who’d been Mets at one point or another; collecting minor-league cards for Mets who’d never gotten a big-league card; making my own custom cards for the nine Mets who’d never had so much as a minor-league card; and making customs for pre-1987 Mets who’d never had a Topps Mets card, as well as extras overlooked by Topps for various reasons. All of those cards led to The Holy Books, three binders that include everyone to play for the Mets in order of matriculation, as well as ’61 expansion pick and Met-on-paper Lee Walls, the managers (full and interim), and the nine “ghosts” who were on the active roster as Mets but never played for the club.

Over time I became more and more intrigued by the marginal players in Mets history, the third catchers and fifth outfielders, the soon-to-be-discarded long men and Plan D spot starters. What struck me was that their major-league summaries on cardbacks or in MLB databases described brief careers when the reality was often the opposite. Those weeks or days or minutes of big-league life were like icebergs, bright points visible at sea that told you nothing about how much invisible mass was below the waterline.

Take Blaine Beatty, who pitched in two games for the ’89 Mets and five more for the ’91 club. Beatty began his pro career in 1986 as an Orioles farmhand, making his ascent to the big leagues a pretty rapid one. He last pitched in the big leagues on Sept. 30, 1991; that winter the Mets traded him to the Expos for another blink-and-you-missed-him player, Jeff Barry. Beatty never pitched in the big leagues again, but his career wasn’t over. He kept playing until 1997, compiling this post-MLB itinerary: Indianapolis Indians, Carolina Mudcats, Buffalo Bisons, Chattanooga Lookouts, Carolina Mudcats (reprise), Calgary Cannons, Mexico City Red Devils, and the Gulf Coast League Pirates. Those two lines of big-league stats obscured 11 years of baseball, played in nine U.S. states and three countries.

Or take Ray Daviault, lifelong Quebecois and momentary ’62 Met. Daviault’s career path was the opposite of Beatty’s: He started playing pro ball in 1953, when he was 19 and spoke only French. His road to the Polo Grounds included these stops: Cocoa, Fla. (Florida State League); Hornell, N.Y. (Pony League); Asheville, N.C. (Tri-State League); Pueblo, Colo. (Western League); Macon, Ga. (South Atlantic League); Montreal (International League); Des Moines, Iowa (Western League again); back to Montreal; back to Macon; Harlingen, Texas (Texas League); Tacoma, Wash. (Pacific Coast League); and Syracuse, N.Y. (International League again) And then, finally, the Polo Grounds. Daviault pitched in Buffalo in ’63, his third stint in the International League, then hung up his spikes at 29.

And finally, there’s the man who introduced me to the concept of the baseball waterline, and was my first card-collecting white whale.

Rich Sauveur pitched 3 1/3 innings for the Mets in June 1991, racking up a 10.80 ERA. My only memory of him is seeing his name on the transaction wire while working in the newsroom of the Fresno Bee; I don’t think I ever saw him pitch in an actual game. But he possesses one of the odder baseball resumes in the history of the game.

Sauveur made his big-league debut on July 11, 1986 at Candlestick Park as a Pirate and appeared in three games that year. He next turned up as a 1988 Montreal Expo, appearing in four games. Then, three years later, he recorded his six games with the Mets. In 1992, he was a Royal for all of eight games. That was it until 1996, when he appeared in three games for the White Sox. Four years after that, he was back at the age of 36 for 10 games with the A’s.

Six teams and six seasons over 10 years. But that’s only what’s visible above the waterline.

Sauveur made his pro debut as a 19-year-old for the Pirates’ New York-Penn League affiliate in Watertown, N.Y., the first stop on this gloriously Daviaultesque travelogue: Nashua, N.H. (Eastern League); Woodbridge, Va. (Carolina League); back to Nashua; Honolulu, Hawaii (Pacific Coast League); Pittsburgh; Nashua again; Harrisburg, Pa. (Eastern League); Indianapolis, Ind. (American Association); Jacksonville, Fla. (Southern League); Montreal; Indianapolis again; Miami, Fla. (Florida State League); Norfolk, Va. (International League); New York; Omaha, Neb. (American Association); Kansas City; Villahermosa, Mexico (Mexican League); Indianapolis again (this time for a shockingly stable three seasons); Nashville, Tenn. (American Association); Chicago; Des Moines, Iowa (American Association); Nashville again (now a truly far-flung outpost of the Pacific Coast League); Indianapolis yet again; Nashville yet again; Sacramento, Calif. (Pacific Coast League); and Oakland.

(You’ve probably figured out by now that Sauveur is left-handed.)

Sauveur last threw — or lets say “hurled,” like Christy Mathewson did — a pitch in anger in 2000, but he’s still in baseball. Last year he was a pitching coach for the Diamondbacks’ Arizona League affiliate. He’s been a pitching coach for 15 years, and three different organizations. That’s a logical second life for an almost cosmically bizarre baseball career. Consider that Sauveur pitched in three different decades but didn’t lose his rookie status until his sixth and final year in the majors. Or that he’s the only player in baseball history to pitch for six big-league teams without recording a win.

He’s also the unwitting poster child for a misfit era of card collecting.

Baseball cards exploded in popularity in the late 1980s, with Topps and its competitors first saturating and then oversaturating the market with product boasting supposed innovations. The most notable of these was the dreaded insert card. Inserts are rare cards seeded randomly into packs of regular cards. They now include autographs, jersey swatches and even cross-sections of bats, but back then they were a little simpler. One of Topps’ early experiments came in 1992, with Topps Gold, which added gold accents and lettering to the regular cards.

Topps’s dilemma: what to do with the checklist cards? Since no one on Earth wanted a gold checklist card, Topps decided to replace them with cards that hadn’t appeared in the regular set. Today, Topps would just make additional cards for the marquee players, but it didn’t do that for the first three years of the Topps Gold era. Instead, the substitutes were fringe big-leaguers, 26th men on rosters passed up for the regular set. I had no idea Topps had done this until the day I stumbled across a 1992 Topps Gold card of less-than-immortal Met Terry McDaniel. As a Mets completist, I needed that card — and cards for the other checklist substitutes. Even if they weren’t Mets, they might have been Mets earlier in their careers, or might show up on the roster one day in the future.

Skip ahead a year, and enter the 1993 Topps Gold Rich Sauveur. It’s #396, a replacement for Checklist 3 of 6 in the regular set. It’s Sauveur’s lone big-league card, on which he’s a member of the Kansas City Royals.

A 1993 Topps Gold Rich Sauveur isn’t impossible to find in the eBay era — according to the Trading Card Database, its median sales price is 19 cents — but eBay didn’t exist back then. At the time, I collected by making the rounds of baseball-card shows around Washington, D.C., zooming in my little red Honda CRX from Laurel, Md., to Leesburg, Va., becoming familiar with Elks Clubs and armories and third-rate hotels.

I also became familiar with baseball-card dealers, and in the early 1990s there were essentially two kinds.

The first kind were lifers, older men or couples who lived in sagging houses out in the sticks whose cellars and attics and rec rooms were crammed with baseball cards. They were fans of the game and collectors at heart, variously grumpy or sweet but always OCD. At shows they’d be surrounded by stacks of card storage boxes, filled with thousands of common cards they’d hauled to the show in the back of a station wagons or a van. They knew players and they knew cards, and they’d let you look for as long as you needed to amass a stack of cards, which usually cost a couple of bucks. And if they didn’t have a card you were looking for, the best of them would promise to exhume it from their holdings and bring it to the next show.

The other kind of baseball-card dealer? Antimatter to their matter. They were people who’d started selling cards because they were hot commodities. Most of them were semi-employed misfits, the kind of serial, darting-eyed grifters who are always hot to make a fortune but dislike the idea of actual work. Today they’re hawking Purell and N95 masks; back in the day they arbitraged Beanie Babies … or baseball cards. At a show, you could spot their tables from two rows away — they invested in fancy metal cases with black fabric linings and glass tops that could be tipped up at an angle to become displays. They almost never brought storage boxes, because to them common cards were by-catch. They’d stand behind their perimeter of display cases, curating their rainbow of gaudily priced inserts, glossy price guide in hand. Few of them knew baseball or liked it, an opinion they’d share freely if asked and sometimes even if not.

Here was my problem. The baseball-card lifers detested inserts, because they flew in the face of tradition and attracted buyers who didn’t care about cards or the game any more than the price-guide chiselers did. If the lifers had Topps Gold cards, they were either mixed in with the other commons or in a box somewhere back at the house. But the grifters didn’t care about Topps Gold either, because they were too low-end to be rare or valuable. There were five or six random scrubs in that set who’d replaced the checklists? Who knew or cared?

I couldn’t find a 1993 Topps Gold Rich Sauveur in 1993. As winter turned to spring in 1994, it seemed unlikely that I ever would. I kept trying, though, spending hungover Saturdays pawing through boxes of cards and having deeply stupid conversations like this one:

“Hey, got any 1993 Topps Golds?”

“Yeah, right here.”

“These are ’94s.”

“Oh. I’ve got a holographic insert Barry Bonds for $20.”

“No thanks, I don’t collect those. I’m looking for a ’93 Topps Gold, one of the cards that replaced the checklist cards.”

“The what? What player you looking for, buddy?”

“Rich SO-ver. It looks like SAU-vee-UR.”

“Never heard of him. Tell you what, I can go $18 on the Bonds.”

Lather, rinse, repeat. It got old.

Until one Saturday pretty much like every other one. I’m at a card show in a sad hotel in Alexandria, Va., one I’d debated not bothering with. It’s in one of those half-ballrooms, with the accordion divider separating the couple of dozen card-dealer tables from the quarterly meeting of the Northern Virginia Chapter of Actuaries. I pay my $2, walk in, scan the room with my by-now-practiced eye and know immediately that I should have stayed home. There are barely any tables with storage boxes — just the usual tipped glass cases maintained by the price-guide set.

I circle the perimeter anyway, because it’s 40-odd minutes back to Bethesda. At one of the tables, I do a double-take. Clipped to the tilted-up display case is a 1993 Topps Gold card. And it’s … Rich Sauveur. The card I’ve been searching for. The one nobody else seems to know exists.

This makes zero sense — Rich Sauveur’s up there alongside the Griffeys and Thomases and Bondses. I talk with the couple whose table it is and they strike me as typical nouveau card speculators. I keep it casual, because there’s only one possible explanation for the sudden elevation of Rich Sauveur to insert-card glory: these people believe this anonymous checklist-replacement card is worth far, far more than it actually is.

But then I do a little math. Suppose they’re overvaluing their Rich Sauveur card by 100X? If so, it should cost me about $5. Am I willing to pay $5 to stop searching hotel ballrooms for Rich Sauveur? I am so, so willing to do that.

“Hey, Rich Sauveur,” I say casually.

The response is not what I expected: “Oh, you know Rich? He’s our neighbor! Rich is a great guy!”

Huh. Still, baseball players do have neighbors, right? We chat about all things Rich Sauveur for a few minutes, a conversation to which I bring relatively little, and then I ask how much they want for the card.

Dead silence.

“Oh, it’s not for sale,” the man says.

“What do you mean it’s not for sale?”

“It’s not for sale,” he says, and I notice his wife has gone stiff and silent.

“I’ve been looking for that one for a while,” I say. “It’d sure be nice to scratch it off the list.”

“Like I said, it’s not for sale.”

At this point I’m actually dizzy. I seem to have fallen through a rip in the space-time continuum, finding myself in a bizarre dimension that obeys the laws of neither physics nor commerce, and from which it’s possible I’ll never escape. It’s all I can do not to scream at these people. Why would you bring a baseball card that’s not for sale to a baseball-card show, the only purpose of which is to sell baseball cards? Why would you … why would … why why why why why why why.

Desperate, I offer them $10. No sale. In fact, they unclip their neighbor’s card from their fancy display case, put it away, and ask me to leave.

Annnnnd scene.

At the time, that story was a yarn about a weird era of card collecting and an OCD quest gone comically wrong. And hey, it still is, But now it’s also a reminder to me of all that you can find below baseball’s waterline. A single card and a couple of lines of stats can be head-scratching or entertaining or both, but provide scant summary for decades of hard work and perseverance and dogged love for a game that makes no guarantees about loving you back.

The postscript, which I swear is true: A week after the Alexandria debacle, I trudged into an equally unpromising card show in Beltsville or Silver Spring or somewhere like that and almost immediately found not one but two 1993 Topps Gold Rich Sauveurs. The guy said they were a quarter each, but sold the pair to me for a dime.

Read more A Met for All Seasons posts.

by Jason Fry on 23 April 2020 10:39 am My Mets fandom begins with Rusty Staub.

My first Mets memory is my mother leaping up and down in our house in East Setauket, N.Y., yelping “Yay, Rusty!” Though that undersells it, actually — that moment is my first memory of anything that I can connect with an actual person or event, as opposed to one of those vague childhood impressions you suspect your brain cobbled together with an assist from old stories and photos. “Rusty, my mom, the Mets” is the earliest point I can recall in which there’s a me interacting with everything that wasn’t me.

And that’s all I recall. The heroic act that had my mom so worked up is beyond reconstruction, except for an educated guess that it happened in 1973 or 1974. The rest of the memory, I suspect, has been filled out and embellished over time. But I think I recall first being a little worried that something had caused my mother to lose her mind and start gamboling about like some crazed faun, and then keenly interested that such things existed. Whatever it was, I wanted in, because it looked like fun.

“Yay, Rusty!” Maybe I could yell that too. And so I’ve spent most of the next 45-odd years doing just that.

If you start young enough, like I did, a first favorite player can be an odd thing. I remember very little of Staub in his first go-round as a Met — nothing about his arrival in April 1972, right on the heels of Gil Hodges‘ sudden death; or about how a broken hand short-circuited his first season in orange and blue; or about his heroics in the fall of ’73; or about his becoming the first Met to crack the 100-RBI mark in ’75. I know about those things, but any firsthand accounts of them have been erased. I can’t reconstruct his batting stance from WOR broadcasts, or recall a day cheering for him at Shea, surrounded by sketchy ’70s people with mustaches and cigarettes and paper cups of bad beer.

So what do I remember?

Three things.

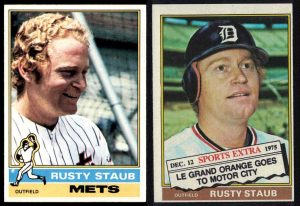

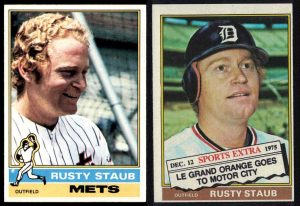

The first is Staub’s baseball card from 1976, the inaugural year I collected. (Which is why, on some level, the Mets’ colors will always register with me as Michigan maize and blue.) It’s a BHNH photo, which is Topps-speak for “big head no hat,” but a rare worthwhile one, because it showcases Staub’s famous and fabulous mane of red-gold, seemingly molten curls.

Danger, heartbreak dead ahead. That hair fascinated me, as did the name Rusty. Kids I knew were named Mike or Melanie, Jennifer or John — or sometimes Jon, just to be confusing. I didn’t know anybody with a name as interesting as Rusty, and was intrigued by the Baseball Encyclopedia’s revelation that Staub’s real name wasn’t Rusty but Daniel Joseph Staub. By the way, Daniel Staub is a terrible baseball name, squat and pedestrian, but Rusty Staub is a wonderful baseball name, half fanciful/friendly and half brusque/no-nonsense. It really is the little things.

Anyway, the name was the second thing. How did that work? Had his parents given him the alternate name Rusty? If so, why hadn’t mine given me a wonderful parallel identity? Or — and this was where the foundations of the world really got wobbly — had Daniel Staub named himself that? Could you do that? Maybe you could, if you were brave and audacious enough — if you were a hero. Which Rusty Staub plainly was. He was my favorite Met, after all.

The third thing I remember about my favorite player was the day he was sent away, to a possibly fictional place called Detroit. That was in December 1975. I don’t remember how I found out, but I do remember shock, fury and desolation. How could this happen? How could the people who ran the Mets yet somehow weren’t Mets themselves — and there was a new and disturbing idea — be allowed to do such a terrible thing? Someone should stop them. I didn’t know if that someone was the president, or Batman, or one of my parents, but the need was glaring and obvious and the fact that the world kept on blithely turning in the face of such an injustice struck me as obscene.

I briefly declared that I was a Tigers fan, which didn’t stick — the Tigers played in some other state and in some other league, which meant they might as well have conducted their business on Mars. But I clung to Rusty’s 1976 traded card (“Le Grand Orange Goes to Motor City,” two terms that were likely mysteries to me), and then to his ’77 Tigers card, an action shot with a shouted crimson A.L. ALL STARS banner along the bottom. That shout, it was obvious to me, was directed at M. Donald Grant, the evil man who was ruining the Mets, and I imagined thrusting my well-loved ’77 Rusty into his face, after which he’d tremble and break down and apologize for exiling Rusty and then for his other crimes. Then he’d go away forever.

Rusty might have been exiled, but no one could take away my most prized possession — a Rusty Staub signature baseball mitt, with his loopy but somehow fussy autograph on the thumb. Therein lay a story. There was no signature Rusty Staub baseball mitt on the market — Staub had a contentious relationship with licensing, which is most likely why he’s MIA from the ’72 and ’73 baseball-card sets. Failed by commerce, my parents fell back on ingenuity. They bought a generic kid’s mitt and a leather-burning tool, and carefully copied Staub’s signature from one of my baseball cards. My mother was certain I’d see through the subterfuge immediately — facsimile signatures weren’t normally thin and brown and faintly redolent of burnt cowhide — but I was innocent in such matters, and none the wiser. I loved my Staub glove and used it avidly though ineptly until even I had to admit it no longer fit. Years later, when I finally found out the truth, I loved it even more.

Staub had a second go-round with the Mets, returning for the 1981 season. Unfortunately, what should have been a joyous homecoming barely registered with me. 1981 was when I fell away from the faith, my interest in baseball eroded away by the strike but also by new pursuits. I was glad Staub was back, but I couldn’t tell you anything he did in ’81, ’82 (the year for which I picked him in A Met for All Seasons is a shrug and placeholder for me) or ’83. Luckily for me, though, he was still around in 1984, when Dwight Gooden brought me back into the fold.

The Staub of ’84 and ’85 was a very different player than my childhood idol — “an athlete and a chef, he looked more like a chef,” in the words of the great Dana Brand. He was basically sessile by then, a ZIP code crammed into mid-80s Mets motley and limited to pinch-hitting. But while he had become a player who only did one thing, he did it exceedingly well. You could almost see him thinking in the on-deck circle and at the plate. Physically he was still, almost a statue in the batter’s box, but mentally he was hard at work, arranging the at-bat so that he’d get the pitch he wanted in the count he wanted. Which he usually did.

He also fed my growing hunger to understand everything that went into excellence on the field. I’d learned the basics of Staub’s life and career as a kid, putting it together from the back of baseball cards and Baseball Digest features. But in the mid-80s I began devouring behind-the-scenes books and articles, and he was a powerful presence in them as well. He was Keith Hernandez‘s superego, the man whose disappointment seemed to sting Keith where he’d brush off the reactions of others, and a self-possessed veteran who’d teach any young player wise enough to listen not only about baseball but also about life, particularly life in the big city. I learned about the book he kept on pitchers, his almost supernatural ability to detect their tells, and that he shared his insights not indiscriminately but with players he thought had earned them.

Staub retired at the end of ’85, and for me the fly in the ointment of 1986 was that he wasn’t there to get a ring as a World Champion — if baseball had stayed with 25-man rosters, would that last roster spot have been Rusty’s? But though he’d retired, he never really went away. He was a Mets color guy for a time, and honesty compels me to observe that as a broadcaster he was a helluva ballplayer. After that he was an éminence grise — or, properly, an éminence orange — showing up now and again for broadcasts and stadium events.

I was old enough now to appreciate the sweep and scope of an extraordinary career and life. Staub debuted with Houston in ’63 as a 19-year-old, but he’d been a Colt .45 before the team ever played a game, drafted in the fall of 1961. He’d collected 500 hits for four different clubs — the Astros, Expos, Mets and Tigers. (Plus 102 for the Rangers, for 2,716 in all.) He was the second player to hit a home run before he was 20 and after he was 40, joining fellow Tiger Ty Cobb. (Gary Sheffield and Alex Rodriguez would later join their club.) He almost singlehandedly won the ’73 NLCS for the Mets, hitting three homers in four games, helping calm a bloodthirsty Shea crowd that wanted to murder Pete Rose, and making a superb catch while smashing into the outfield wall. That collision wrecked his shoulder, leaving him unable to throw; somehow he still hit .423 in the World Series.

And he was just as interesting off the field. He’d been an activist for himself and for players in general before the Messersmith-McNally decision, with his outspokenness and daunting intelligence precipitating his departure from the Astros years before it led to his trade from the Mets. Traded to the Expos (another team yet to play a game), Staub found himself frustrated that he couldn’t understand young fans who addressed him in French. So he learned the language, an effort that made him beloved in Montreal. And he loved Montreal back, embracing the city’s culture and love of wine and food. He loved New York with similar fervor, opening restaurants and starting charities, raising millions for food banks and children of police officers and firefighters who’d died in the line of duty.

Rusty also kept popping up in my day-to-day life. In September 2004 I ran the Tunnel to Towers race through the Battery Tunnel to the World Trade Center site, and perked up before the race when I realized Staub was one of the dignitaries called on to say a few words. Afterwards, I spotted a familiar figure walking by himself down West Street. Was that really him? It really was. I froze, then got up my courage and ambled over to him, only to discover I was more nervous than I’d realized. Rusty, no fool, never broke stride as I peppered him with inanities. When I finally managed to say what I should have said in the first place — that he’d been my favorite player as a kid and I’d just had to tell him that — he thanked me and said that meant a lot.

I immediately regretted not telling him the story about the glove, and so was surprised and delighted to catch sight of him a few months later in the San Francisco airport. This was my chance! Before I could close to “Hey Rusty!” range, though, he sensed danger and made a neat sidestep into the men’s room. That was enough to check my enthusiasm; I decided to let Rusty be.

And so I did. He kept popping up anyway — a couple of months after that I was in New Orleans and wound up riding to the airport with a cabbie who’d played high-school ball against him and his brother Chuck, and regaled me with stories about both of them. (One more Rusty factoid: Ted Williams flew down to New Orleans to recruit him personally.) I gave the cabbie a ludicrously large tip, pleased by yet another Rusty encounter, even if this one was once removed.

Staub died on March 29, 2018, and at first it seemed incomprehensible that my first favorite player could be gone — and on Opening Day, no less. But in mourning his death, I realized that through sheer dumb good fortune, my first favorite had been a perfect choice. He’d been a Met when I was a child who just wanted to hoot and cheer, one who came with a cardback full of interesting factoids to memorize and recite. He’d returned to the Mets when I was a teenager fascinated by the mental aspect of baseball and its hidden workings. And he’d stuck around as an alumnus when I was an adult curious about interesting lives and currents in the game’s history. He was gone, tragically, but he’d never be forgotten, not by me. How could he be? After all, he’d been there from the beginning.

Read more A Met for All Seasons posts.

by Greg Prince on 21 April 2020 1:08 pm Starting today and slated to appear in this space every Tuesday and Friday in the weeks and months ahead is a new Faith and Fear in Flushing series: A Met for All Seasons. In it, Jason and I will consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Here’s the background: We conducted a draft nine years ago when a semblance of this concept first occurred to us; one of us would do this player for this year; the other of us would do that player for that year; and so on. The “so on” became nothing except for an occasional “hey, remember that thing we were gonna do?” Luckily, we’d each saved our draft lists. Thus, a little while ago, once we realized we weren’t going to be busy recapping games for the foreseeable future, we extended the draft eligibility period, held some supplemental rounds, implemented a compensation pool (allowing us to replace any selections we’d rethought since 2011, given that it worked so well for the White Sox in 1984) and certified our choices.

Now, after nearly a decade of talking and not talking about it, we each have thirty players bearing the banner for a particular year and will set out to explain, to some extent, why we chose who we chose and what they mean to us as Mets fans. Some weeks I’ll go Tuesday and Jason will go Friday; some weeks it will work the other way around. (Coincidentally, Jason and I once went in on a Tuesday/Friday ticket plan.) The seasons we’re covering are 1962 through 2021, the last couple encompassing an air of mystery or perhaps optimism. The Mets we’re talking about will be revealed in due time. We’d like to think they represent a decent cross-section of the Met experience over the nearly sixty years there’ve been Mets, but maybe we just picked players we wanted to write about. The order in which they’ll appear is non-chronological.

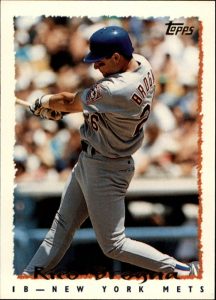

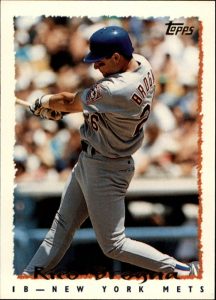

For example, I’m starting with 1994 and my Met for that season is Rico Brogna.

Rico Brogna is my Met for 1994 as a person, I suppose, but probably more as an idea. I think I’m going to find out as we do this that I tend to think of ballplayers as ideas as much as I do people. I have it on good authority — hell, I’ve witnessed it for myself — that ballplayers are people, too. We probably forget that from time to time, considering we only know of these people because they are ballplayers. That’s generally good enough for us, the fans.

We’re people as well, but we’re talking baseball here.

I immediately think of Rico Brogna when I think of the 1994 Mets season because of the idea he represented to me coming out of that strike-shortened year. Rico Brogna was who and what I wanted to come back. He’d brought me hope and I figured he could only deliver more. I was going to hold tight during absent August, silent September, ohfer October, the long, even colder winter, and the farce spring when MLB lured replacement players to wear their clubs’ uniforms in games that didn’t count, threatening to keep them around for games that did. By April 26, 1995, the latest the Mets have ever opened a season (until 2020, if they open one at all), I should have been fed up with baseball, which didn’t even have the dignity to be around for months on end to let me be fed up with it.

Instead, I kept hanging tight, waiting for Rico and welcomed back the whole package, lock, stock and Brogna. Twenty-five years later, deep in a void that superficially recalls the lack of baseball wrought by the 1994-1995 strike, I can’t say it was Rico Brogna the person or even Rico Brogna the player I wanted. I wanted Rico Brogna the idea.

Rico Brogna debuted as a Met on June 22, 1994. I had never heard of him despite his having been a first-round draft pick of the Detroit Tigers in 1988. He came up to majors four years later, played nine games, and returned to Triple-A Toledo for another year. I missed it when the Mets traded their own former first-rounder, Alan Zinter (1989), for Brogna four days before Opening Day 1994. The Mets were busy that week. They picked up David Segui on March 27, Jose Vizcaino on March 30. So overcome with joy that the 1994 Mets would be even more materially different from the nightmare 1993 Mets, I guess I didn’t squint all the way to bottom of the transactions box for March 31 to see this extra move.

With Vizcaino at short, Segui at first and Brogna assigned to Norfolk, the post-apocalyptic Mets got off to a modestly brilliant start in 1994. Anything that wasn’t indicative of another 59-103 record would have struck me as modestly brilliant. The Mets swept their first three in Chicago, returned to Shea for their Home Opener with a winning record and levitated themselves four games over .500 after 32 games. In New York in May 1994, with all five winter sports teams having made the playoffs — and the Knicks, Rangers and Devils all legitimately carrying championship aspirations — it felt like nobody outside the hardest core of Mets fans was paying attention. But I was, and I was delighted that the Mets were, after a three-year dip in fortunes, kind of OK again.

The high times of 18-14 didn’t last, but I was slow to get the memo. I didn’t want to read it. I was convinced the Mets were pretty good. Alas, the dark side of .500 beckoned for keeps in early June. Fifth place in the newly aligned National League East, which is to say the basement, loomed as our summer home. I didn’t maintain any allusion we could keep up with the Expos or Braves or anybody else vying for the new Wild Card, but I just liked that the 1994 Mets weren’t the 1993 Mets anymore. I wanted them to quit reminding me a year hadn’t passed since they were the 1993 Mets.

The Rangers won the Stanley Cup on June 14. The Knicks took the Rockets to the seventh game of the NBA Finals on June 22. In between, David Segui went on the 15-day disabled list, necessitating the promotion from Norfolk of Rico Brogna. I know which one of those sports stories resonates most for me now, but like I said, I didn’t know anything about Rico Brogna then. I was only getting used to him replacing Segui on June 28 when word came down that Dwight Gooden — who’d pitched Opening Day in Chicago and still reigned at least titularly as ace of the Mets’ rotation — tested positive for cocaine and was about to be suspended, just as happened in 1987. Doc, my favorite player ever since he first emerged as breathtaking Dr. K, went through rehab seven years before and was welcomed back as if not a hero, then definitely as family. In 1994, he was essentially kicked out of the house. There was little in the way of acknowledging addiction as a disease, just disbelief that this was happening a second time, how could anybody with so much to lose be addled enough to lose it? Yup, the Mets were finally getting headlines.

On the night the news of Doc’s KO broke, Rico Brogna started his third consecutive game for the Mets and, for the third consecutive game, recorded a pair of hits, including his first National League home run. The Mets lost, falling ten below .500 for the first time in 1994, but Rico raised his average to .333.

Without meaning to, Rico Brogna filled the opening for my favorite player before I had time to place a classified. Doc wasn’t around. Rico was. I learned about him. He was 24, born in Massachusetts, but grew up to become the pride of Watertown, Conn., from whence he was drafted. Played high school football well, we heard. Became buddies with the pitcher called up to take Doc’s spot in the rotation, Jason Jacome (pronounced hock-a-me). They were spotted palling around on a West Coast trip, the two new guys grabbing tenuous hold of the steering wheel for a franchise that had once more lost its way. In 1984, it was Gooden joining forces with Strawberry. In April it was Segui and Vizcaino. Now it was these two newest newcomers, 24-year-old Rico, 23-year-old Jason, a couple of lefties from out of nowhere. On July 7, in his second start, Jacome shut out the Dodgers, lifting the Mets to their sixth win in eight games since the night Doc was disappeared. Segui was back from the DL, but was planted for the time being in left field. A good glove man through his career, David was nonetheless Wally Pipped.

When baseball returned, Rico would be back with it. It would take a little while for Rico Brogna to settle in as a new age Lou Gehrig. There was a bit of slumping in California, but the Mets came home and the bat reheated. Rico’s average rose over .300 to stay. The Shea PA played “Rico Suave” when he’d get a big hit, briefly leading me to believe Brogna was Latino. I wasn’t corrected in this conception until some guy behind me at a game told his companion, “Brogna — that’s the Italian kid.” I didn’t care what Rico Brogna was other than that he was the Mets’ first baseman.

On July 25, a Monday night (I don’t have to look up the date or day), Rico Brogna exploded fully upon the Metropolitan-American consciousness, certainly the slice that was attempting to tune into The Baseball Network. The Baseball Network is hard to explain all these years later. It was hard to explain in 1994. Eschewing the “Game of the Week” motif as hopelessly outdated, MLB decided to have what amounted to a series of nationalized regional telecasts, with in-market exclusivity for particular games, which meant on a given weeknight, maybe you saw your favorite team, maybe you didn’t, no matter that they were all scheduled to play, no matter that cable networks existed in summertime to show baseball games. Sometimes New York got the Mets, sometimes it got that other New York team. And if the first-place Yankees ridiculously took TV precedence, the Mets were confined to radio. Got all that? Also, though these games aired on ABC, they were not announced by, say, Al Michaels. You got an announcer from one team and an announcer from another team and that was your crew. Actually, that was a pretty decent feature. Suddenly Bob Murphy was sometimes doing TV. On July 25, with the Mets in St. Louis and somehow rating preferential treatment back home on Channel 7, it was Gary Thorne, at this point part of the WWOR-TV booth, and Al Hrabosky.

They wound up co-hosting, live from Busch Stadium, The Rico Brogna Show. With as much spotlight as the 1994 Mets were going to garner, the young man from Connecticut raised his and therefore our profile. Brogna sizzled in St. Loo, going 5-for-5, making him the first Met to register five hits in one game in six years. His biggest hit was a two-run double that keyed a five-run fifth, giving Bret Saberhagen all the support he needed to cruise to a complete-game 7-1 win. Rico came into the game batting .333. He came out of it batting .377.

“I guess he’s what you would call a manager’s delight,” Saberhagen marveled. “It’s probably a night that I’ll remember for quite a while,” Bret’s first baseman allowed, humbly adding, “Some of the balls found some holes.”

Yes, sir, the 1994 Mets were rising like the mighty Mississippi. At least to me they were. They escaped the cellar. Saberhagen had made the All-Star team by walking basically nobody. Second baseman Jeff Kent showed he could hit a ton if not field quite as much. Vizcaino was a genuinely reliable all-around shortstop. Jason Jacome was en route to a winning record and the Mets began flirting seriously with one of their own. And Rico Brogna? He had, in my mind in about a month, ascended total obscurity to next big thing to biggest thing there could be, albeit on a limited scale.

Two-and-a-half weeks later, it all stopped, because the owners wanted to institute a salary cap and the players wanted no such thing and no compromise was forthcoming. On August 11, all the baseball on all the channels went dark and stayed dark. The blackout remained in effect clear through what was supposed to be the postseason, an affair that wasn’t remotely likely to include the 55-58 Mets, but I wasn’t aiming my sights that high one year after 1993. The previous August, former Cy Young winner Saberhagen was known mostly for blasting bleach at reporters, and former stolen base champ Vince Coleman was living down his contretemps that involved tossing powerful firecrackers at fans in the Dodger Stadium parking lot. Bobby Bonilla had been making threats, Eddie Murray snarled his hellos and everybody was stuck in a seventh-place snit. It was enough in August of 1994 that the fresher-faced third-place Mets were closing in on .500. It would have been great had they been granted the opportunity to reach it and hover above it.

After 113 games, almost .500 would have to do. I had that to cling to — that and seven home runs, twenty runs batted in and a .351 batting average I hadn’t anticipated in the slightest out of that fine young man from Watertown in his first 39 games as a Met. I had an idea of what Rico Brogna could do. I had an idea that Rico Brogna would keep making the Mets better. It would have to tide me over until whenever there’d again be baseball.

And it did.

by Greg Prince on 19 April 2020 4:12 pm This Sunday afternoon in New York has been sunny if chilly and breezy. Tonight will be chillier, probably as breezy and a whole lot darker. If this Sunday afternoon were a Sunday afternoon as originally conceived, I’d be sitting around complaining there’s no Mets game on because it’s being held in abeyance for Sunday Night Baseball.

That would be a great complaint to make right now.

I’m still sort of tracking the 2020 Mets schedule despite it having been rendered inoperative by prevailing circumstances, thinking to myself every day or two that if the Mets were playing, this is where they’d be playing and this is what might be going on. In doing so, I’ve gone through an array of phantom-limb sensations.

Opening Day.

The gaping off-day void that follows Opening Day.

The probable first rainout.

The inevitable first loss (because you can’t win ’em all).

The disbelief they’d be playing in this weather.

Knowing in my bones that the Mets would be not so great, not so bad and that the emerging effect would register as not so satisfying.

The trip to Washington, where our resentment levels would have risen about as high as their championship flag.

The trip to Houston, where there’d have been ONE pre-series storyline and it wouldn’t be Jake Marisnick’s triumphant return.

The trip to Milwaukee, when I would have mentioned, as I do upon every trip to Milwaukee, that the Mets always lose their second-to-last game in Beertown.

The well-meaning Jackie Robinson Day mandate that every player on every team don 42 and the slight chuckle the invocations of Ron Taylor, Ron Hodges and Roger McDowell still elicit annually.

Disdain for Saturday night home games in April.

Disgust for Sunday night games anywhere anytime.

It’s almost as if we don’t need a season to be fans. But we do. For although there is much about absorbing baseball that is familiar enough to perform by instinct, there’d be something going on these first few weeks of 2020 that we couldn’t know about.

I can’t tell you what it was or is or would have been. Finding out what is why we keep coming back. If every season was a simple recycling of occasions and themes, the computer simulations I’ve mostly avoided would do. But the unknown is what you can’t program, no matter how sophisticated your software. You can imagine your head off (surely you have time to do so), but during a baseball season, the most unlikely or outrageous outcome you can imagine is no match for the thoroughly mundane that constitutes the fiber of our existence. We need that low hum of grounders to short and fouls into the crowd. It’s from the swelled ranks of the totally expected that one unanticipated aberration rises up and grabs our attention. Next thing we know, something we didn’t see coming lodges in our consciousness. Suddenly it’s a part of how we view baseball from here to eternity.

To borrow a phrase coined by my friend Sharon when I was crafting the original Happiest Recap series in 2011 (most Amazin’ first game of a season, most Amazin’ 137th game of a season and so on), I adhere to the Metropolitan Calendar more than the Gregorian one the rest of society uses. When retracing Met steps — for example their record at a certain juncture of a certain season — I like to think in terms of where they were after ‘x’ number of games rather than where they were on such-and-such a date. Comparing records after ‘x’ number of games gives me a comparable playing field. The Mets have opened seasons on March 28, April 26 and sixteen dates in between. On April 26, 2019, when the Mets had been playing for close to a month, their record dipped to 13-12. On April 26, 1995, the Mets were freezing in Denver, saddled with a mark of 0-1 following the finally resolved baseball strike of the previous summer, autumn and winter and, at last, Opening Night at brand new Coors Field. You can see why I might find limited utility in contrasting what those two editions of the Mets were up to on April 26.

Beyond exactitude issues, I’m rather fatigued by “This Date In…” reminders. I have been for about a decade. I used to love being reminded — and reminding others — that on this date in some past year something Metwise happened and, say, wasn’t that something we haven’t thought about in a while? Because such information is so readily searchable, you can’t scroll six socially responsible feet on your feed of choice without being inundated with this or that having happened this or that many years ago. It was more fun when it wasn’t as easily accessed, which is to say it was more fun when it was left to people with unusual capacity for retaining day & date details (ahem) to the reminding, whether or not anybody else was in the mood to be reminded.

Nevertheless, I’ve picked up on a couple of those helpful reminders over the past couple of days and I’m glad I did, not so much for the facts that have resurfaced, but to realize that with every game and every swing and every pitch, we get new facts. On April 17, 2010, we received a torrent of them because the Mets and Cardinals played twenty innings that weren’t technically endless but essentially were. On April 19, 2013, we calibrated our common tongue to incorporate the wonders of how we reacted to our young and promising ace outpitching somebody else’s young and promising ace. That was the night we chanted, with all relevant evidence tilting in our enthusiasm’s favor that HAR-VEY’S BET-TER! On that night precisely seven years ago, there was no disputing our assertion was anything but fact, just as on the afternoon into evening of ten years and two days ago, there was no escaping the sense that there’d be no escaping a game that would never end.

Maybe you remember what happened the game before or after the Mets beat the Cardinals in twenty innings or the game before or after Matt Harvey overwhelmed Stephen Strasburg. Probably you don’t. That’s all right. You probably remember the two games in question, though. They became an element of your fandom. Maybe not the most definitive or compelling elements, but they’re there. You might not recall the exact dates or even the seasons they occurred without a nudge, but somewhere in the back of your mind, the games or at least the takeaways from them are there. Sometimes, as on April 17, 2010, games seem to stretch beyond their reasonable parameters. Sometimes, as on April 19, 2013, pitchers get us so excited that we don’t only want to watch them with awe, we need to describe them aloud.

And those were only two games among 162 games in their respective seasons among who knows how many thousands you’ve experienced through your life? If April of 2010 hadn’t included a slate of Mets games, you wouldn’t have a specific point of reference involving a twenty-inning win at Busch Stadium in which Tony La Russa resorted to pitching position players and Jerry Manuel warmed up Francisco Rodriguez enough so that K-Rod threw the equivalent of a complete game in the bullpen. If April of 2013 had proceeded without the Mets, you wouldn’t remember that there was a span of weeks when everybody talked about Matt Harvey as the next Tom Seaver and it was rarely interpreted as hyperbole.

So much to glean from two memorable baseball games ten and seven years later. So much to glean at the time from the now forgotten baseball games surrounding them. So much to inform our perspective as we roll along. So much to reach back and touch for a few minutes when there’s nothing of a similar nature emerging to engage never mind not depress us. It’s all a part of our baseball fandom.

This April we’re not adding to it, which is a real shame, if merely incidental to the larger picture painted by these unfortunate days.

Without new baseball, I’ve reveled, to a point, in the old baseball broadcast by outlets whose archives are a seemingly shallow blessing. Listen, if you want to air The First No-Hitter in New York Mets History and I happen to notice it’s on, I will greet its closing moments with a substantial semblance of the rapture I experienced and expressed on June 1, 2012. But don’t expect me to make a night of it when you have aired The First No-Hitter in New York Mets History so many times that the total outpaces the viewer’s ability to count, maybe find another game to show.

SNY has been running an online survey in an effort to determine what Mets fans think is the greatest game of the last decade. They are providing a list of five choices — the no-hitter; Wilmer’s tears of joy; David’s return to the lineup wherein eight Met home runs were hit; the 2015 division clincher; and David’s farewell — and will televise them in ascending order this Monday night through Friday night, five through one. All five have been shown repeatedly. All five have been repeated repeatedly. Then they went into reruns and were rerun rerunnedly. After which, they went into a rotation so heavy that MTV c. 1983 was embarrassed that a cable channel could play the same few hits over and over and over.

Maybe find another game to show? Definitely find another game to show. We are hungry like the wolf to watch something besides the same dozen games in a loop.

Show the last game the Mets played before they’d ever had a no-hitter.

Show the first game the Mets played after they’d finally had a no-hitter.

Show David Wright going two-for-four with a double amid Jon Niese going six innings giving up four runs to whoever, it doesn’t matter.

Delve into that SNY library and do what you did for the first week or two of the great postponement. The network aired every 2019 win it aired last year, not just the so-called classics. Pete Alonso didn’t necessarily homer. Jacob deGrom didn’t necessarily toss eight scoreless. Nobody’s shirt was necessarily giddily detached from anybody’s sweaty torso. It was just one baseball game after another and it was quietly exhilarating amid a silent spring. We didn’t require additional suspense or intrigue. I didn’t require it be a Mets win, but I can understand if others aren’t so expansive to their approach to rewatchables.

I hoped that once SNY got done with the wins from 2019, they’d cue up the wins from 2018, then 2017 and keep going clear back to 2006, the first year there was SportsNet New York. Perhaps, if it didn’t require anybody to endanger their health or cross constricting contractual boundaries, they could arrange to pop on Mets games that predate SNY. This topic usually quickly descends into “SHOW THE JIMMY QUALLS GAME!” or some other vintage fare that one can be pretty sure doesn’t exist on tape or film fifty-one years later. I’m all for wish-listing, but I’ll be reasonable here. I’m not asking for video miracles. I’m asking for Brian Bannister and Moises Alou and Cory Sullivan and maybe a little Josh Satin. If a digital treasure chest of Fran Healy wishes to spill its secrets regarding Shane Spencer settling under a can of corn or Esix Snead coming into run with blazing speed, wonderful. Anything older, fantastic. Anything, really.

Nobody has to be walking off. Nobody has to be nailing down a Cy Young. Just fill the rest of our April with what we don’t have in front of us, and then do it again in May and June and we’ll let you know when you can stop.

by Greg Prince on 11 April 2020 6:27 pm Major League Baseball, assessing myriad proposals, has discussed a radical plan that would eliminate the traditional American and National Leagues for 2020, a high-ranking official told USA TODAY Sports, and realign all six divisions for an abbreviated season. […] The plan would have all 30 teams returning to their spring training sites in Florida and Arizona, playing regular-season games only in those two states and without fans in an effort to reduce travel and minimize risks in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The divisions would be realigned based on the geography of their spring training homes. […] Financially, it could be a huge boon for the TV rights holders. You could have a captive TV audience the entire day. […] The DH would likely be universally implemented as well.

—Bob Nightengale, USA Today, April 10, 2020

“We will not have sporting events with fans until we have a vaccine,” says Zach Binney, a PhD in epidemiology who wrote his dissertation on injuries in the NFL and now teaches at Emory. Barring a medical miracle, the process of developing and widely distributing a vaccine is likely to take 12 to 18 months. […] O.K., but what about empty stadiums? “The idea of a quarantined sports league that can still go on sounds really good in theory,” says Binney. “But it’s a lot harder to pull off in practice than most people appreciate.”

—Stephanie Apstein, Sports Illustrated, April 10, 2020

Yes, we all need a room of our own.

—Billy Joel

Seen the leagues go on hiatus

I saw the teams try quarantine

’Cause life went still across the USA

We all wore facial masks

And tried hard not to breathe

They schemed a scheme to restart playing

And broadcast content good to go

They shoved the DH in

Remade divisions

Like in MLB The Show

I’ve seen the leagues go on hiatus

I saw no people in the seats

At first it sort of seemed to make some sense

We’d see it from our homes, just watching on TV

They opened parks around St. Lucie

Like stuck inside an endless March

No fans allowed in there

The owners didn’t care

They had some programming to stream

I’ve seen the leagues go on hiatus

I saw the Mets play ’til late fall

DeGrom and Ramos formed a battery

Robotics called the strikes

And electronic balls

They tried creating stringent guidelines

Confining most all personnel

They said cameras could stay

Shooed families away

Pretending all of this was swell

Our ancient leagues, before hiatus

Gave us the game we came to know

They didn’t haul the sport to Florida

And turn the stadiums into a studio

Perhaps soon we won’t remember

This awful godforsaken year

I hope that once we’re fine

Then we can take in nine

Where all can gather without fear

by Greg Prince on 6 April 2020 4:10 pm As of tonight’s off night, per the current non-operative schedule, the 2020 Mets would have played eight games already. They were slated for nine, but the second of them, on Saturday, March 28, would have been rained out. I can’t prove that — I can’t prove anything where the 2020 Mets are concerned — but it rained all day in New York two Saturdays ago, and not even the large gate attached to a Pete Alonso Bobblehead Day seemed likely to pull the tarp from Citi Field’s diamond. In context, the rainout would have caused consternation and chaos in modest doses. Context ain’t what it used to be.

So let’s say the Mets would have played eight games by now. Let’s figure BobblePete would have found a makeup day to nod agreeably. Let’s assume, which you can never do in normal times, whatever those are, that the pitching would have been pushed back to a point, meaning the optimal utility of Jacob deGrom, whose Bobblehead Day dawned dry enough to play on March 29, didn’t get leapt over during the season’s second week, which, if you’re not scoring at home (though you’re likely doing everything else there), was just last week. I know, I know; who can tell anymore?

DeGrom in the Opener. Stroman that succeeding Sunday, which was three days later. Then Porcello, Matz and I gotta believe deGrom again, because you don’t want him sitting and waiting for a week. Wacha in Washington for their disgusting flag-raising and so forth. Then it’s another day off, followed by Stroman on Saturday, going on five days’ rest and, I guess, Porcello Sunday, a.k.a. yesterday. We arrive in Houston, packing righteous indignation and who to pitch? You can use deGrom on proper rest tomorrow or you can keep Matz from going altogether stale.

You’d use deGrom, right?

I don’t know who Rojas — and the calls Rojas would have gotten from Van Wagenen that Rojas would already be getting a little edgy from — would have chosen. I don’t know what would have happened in the eight games the Mets would have played by now. Without indulging in the well-meaning simulations out there that I can’t bear to look at, I have a hunch the Mets would be somewhere between 3-5 and 5-3 after eight games. It’s just a hunch. The Mets haven’t been 5-3 after eight games since 2017, 3-5 since 2016 or 4-4 since way back in 2011 (I’ve lived long enough that 2011 now qualifies as “way back”). It just feels right that these Mets would be settling in somewhere between a little better than .500 and a little worse than .500.

I could be wrong. I could be absolutely wrong. The Mets were 7-1 two years ago, 6-2 last year. They’ve never been 8-0, but there are six instances of them being 2-6 (most recently way back in 2010) and three times when all they had was one or zero wins. But I’m a little too hypothetically optimistic to think they’re as bad as they were in 1962, 1963, 1964 or, for that matter, 2010. Just call me wide-eyed. Or Zoom me any adjective you like.

Scenarios:

The Mets are 3-5. We are healthily panicked, just ill at ease enough to fit the circumstances. Three wins and five losses after eight games is not a good look. We are reminding ourselves multiple times a day that there are still 154 games remaining, and even if somebody among Washington, Atlanta, Philadelphia and Miami (hey, you never know) is off to a 7-1 launch, well, there are still 154 games remaining. After losing five of eight to start the season, we are trying to not doubt Luis. We are trying to not doubt whichever element of the staff, starting or relieving, we deem culpable for 3-5. We’ve probably called for and will receive by tomorrow night some change to the batting order and maybe somebody who’s been mostly glued to the bench entering the lineup. Just a scheduled off day for Cano, Luis will say. Just letting Amed clear his head, maybe. Say, how’s Conforto’s oblique, anyway?

The Mets are 4-4. We’re not thrilled, but we’re not overtly hostile. Four wins and four losses after eight games is what our record says it is. It’s OK. It’s not great, because we’ve already experienced the agony of defeat four times, and that’s three times too many. Jason or I wrote that first “so we won’t go 161-1” column and we all ingested easily enough the reality that there are a third you win, a third you lose, et al. But a team we fancied jumping up to immediate playoff contention muddling along doesn’t strike us as a an adequate break from the blocks. Somehow 4-4, doesn’t feel 125 percentage points better than 3-5. Not much of a sample size there from to which to judge, of course. Then again, we have zero sample size in actual 2020, so I’d take 4-4 over 0-0 ASAP as long as nobody spreads or catches anything from it.

The Mets are 5-3. That’s not bad. That’s more than not bad. But if we’re 5-3, why aren’t we 6-2? You know if McNeil had gotten that base hit with the sacks full, we’d be 6-2. You know Alonso is gonna finally belt one and more will follow once he loosens up, and it’s pretty good that we’re pretty good with the Polar Bear obviously trying a little too hard. Familia’s weight loss has made a difference. Brach may be the secret weapon. And what about that running grab Marisnick made? Luis putting him in for defense really paid off. Still, it feels like they could be better than 5-3. But we shouldn’t be complaining. It’s just eight games.

If only.

by Greg Prince on 1 April 2020 3:09 pm EDITOR’S NOTE: To help us through these troubled times, today we dig into the Faith and Fear archives and share posts that some of our longtime readers might get a kick out of seeing again or our newer readers might enjoy checking out for the first time. This one originally ran on November 10, 1980, part of an annual series we still publish to this day.

So, when did you know or at least have an inkling? That day in May when we blew one to Cincinnati only to suck it right back? A couple of weeks later when we went into shall we say overtime to skate away with a cup of satisfaction? You couldn’t deny it come the middle of June. By then, it was obvious. It poked its head into our faces most of the rest of summer, and even peeked out at us from behind clouds as September closed.

But you knew it was there. You could practically feel it in your hands. You could hold it close to your bosom, certainly in your heart. In your head, maybe you were never so sure, but this isn’t about the head. It was only a little about cold, hard statistics.

It was all around us, though. It defined us. We embraced it and embodied it. Hell, we were “we” again, and it made us want to go “wheeeeee!”

That’s why Faith and Fear in Flushing has selected The Magic as the Manufacturers Hanover Trust Mets Player of the Year — an award dedicated annually to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates or transcends the year in Metsdom — for 1980. The Magic was, indeed, Back. And if it wasn’t “better than ever,” it made things around here as good as it could have possibly gotten under the circumstances.

You know The Magic. You were introduced to it by brand name in April, via a series of newspaper ads, and you’re pardoned if the first thing you did was smirk. “The Magic is Back,” they said. “What Magic?” you asked. Weren’t these the same Mets we suffered through in 1979, give or take Richie Hebner for Phil Mankowski and Jerry Morales? We were supposed to be excited that Abner Doubleday’s great, great, grandnephew or whatever he is bought the team? That the guy who ran the Orioles when we beat them in legitimately Mets-magical 1969 was the new GM? Really…what Magic?

The ads said something about the “New Mets” being “dedicated to the guys who cried when Thompson connected with Branca’s 0 and 1 pitch” (and, yes, the ad misspelled Bobby Thomson’s last name; consult the Baseball Encyclopedia, why don’tcha?). I don’t know what ancient Brooklyn Dodger complaints have to do with the New Mets (and doesn’t our orange “NY” imply maybe some Mets fans have fond Giant memories?). At first glimpse, it was a swing and an I don’t know what. The TV commercials were a little on the weird side, too. Whistling “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and reminding us that long ago the Mets were good.

This was the Magic were selling?

Yet you can’t say the Madison Avenue phrasing didn’t catch on. The back page of the Post, over a picture of a mostly empty Shea Stadium snapped while the Mets and Expos were busy playing, captured the early reaction to the campaign: MAGIC GARDEN. Ha-ha. Let the record show that the Mets defeated Montreal, 3-2, in front of 2,052 souls on the afternoon of April 16, no matter what the Post wanted to poke fun at. I listened to that game on the radio. I would have been there had it been possible. So would have you. We didn’t need selling. At most, we needed a ride.

Let the record also show that that game was our first come-from-behind win of the year. It wasn’t a terribly dramatic comeback. We were down, 1-0, to Bill Lee when we cobbled together four singles in the third to create three runs (and then not blow it). It was a 1980 Mets kind of rally, more effective than showy, yet it showed anybody who was watching or listening that maybe the Mets didn’t have to stay buried when behind — and that they could be good company.

Still, The Magic was mostly a punch line. The Mets were telling people it was Back when the baseball part of the equation (the 1980 version, not 1951 or whenever) wasn’t cooperating. On April 16, we were 3-3. By May 13, we were 9-18 after losing in Cincinnati. Final score: Reds 15 Mets 4. The Reds scored eight runs in the fifth inning. Ray Knight hit a pair of home runs…in that inning. Ken Griffey hit one, too. Going to the library and looking up those box scores all these months later makes for a frightening experience, and that’s before glancing at the covers of Time, Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report. Never mind the hitting or lack thereof. Who gives up fifteen runs to the Reds? Burris. Pacella. Kobel. Bomback. Glynn. Hausman. Weren’t we a team always known for our pitching?

You wouldn’t have guessed things were about to get better. You wouldn’t have been thinking about The Magic, either. Maybe you still weren’t the day after, not in the bottom of the ninth, when — with Craig Swan on the hill and a 6-2 lead feeling as secure as Linus Van Pelt does when clutching his blanket — it all began to slip away again. Driessen doubles. Knight singles him in. Reardon enters and, not too many pitches later, Harry Spilman blasts a three-run homer to tie it at six.

Harry Spilman? Good grief!

Before we could all line up at Linus’s sister Lucy’s booth with our nickels out for Psychiatric Help, the Mets of all people gave us aid and comfort in the top of the tenth. John Stearns doubled. Jerry Morales (thanks, Hebner) singled. We led, 7-6. Then Jeff Reardon made up for that messy ninth-inning Spil by quickly picking up for his mistake. by retiring three dangerous Reds — Concepcion, Foster, Driessen — with a bounty of tidy relief. It felt like a save, because the Mets had saved their dignity, but rules are rules, so Jeff was awarded the vultured win. Somewhere, Phil Regan smiled.

Can you feel the excitement? Only in retrospect, for the Mets were 10-18, and a good day in Cincinnati maybe gets you to Columbus. But it’s November now, and we have the benefit of hindsight. We know The Magic was bubbling under the surface. Or the ice, if you will. On May 24, like any good Long Islander, I was switching back and forth between the sixth game of the Stanley Cup Finals on Channel 2 and the thirty-sixth game of the Mets season on Channel 9. They both went into extras. They both wound up 5-4 in favor of New York. Admittedly, what was going on in Uniondale was a bigger deal than the events unfolding in Flushing — the Islanders had finally won a Stanley Cup — but if you couldn’t see the parallels between Bobby Nystrom scoring at 7:11 of overtime and Elliott Maddox driving in Lee Mazzilli in the tenth inning, well, you just weren’t trying.

But the Mets were. They were trying and they were succeeding. Maybe the crowds at Shea could only fill half of Nassau Coliseum, but word was getting out that the Mets were not only not always losing, but they were making a little bit of a habit of winning. That Saturday we beat the Braves in ten came after a Friday night when we beat them in nine and before a Sunday when we shut them out in regulation. We swept a three-game series! Since when do we sweep three-game series?

Since when do we speak in terms of “we”? Have we always been so first-person pluralistic about our team, or did we take a hiatus sometime after 1973? Let William Safire track trends in language. In 1980, we felt anew that the Mets were ours.

That was The Magic in action in ways you couldn’t see. Soon, however, we’d have plenty of evidence in ways we could reach out and touch like the phone company only wishes we would (when we’re not busy calling Sportsphone for Mets updates, that is). Soon, The Magic was on the line. You couldn’t put it on hold any longer. And calling in from Hollywood, it was Casey Kasem to tell us that climbing the charts was the song about to serve as soundtrack for our surge.

You have to believe we are magic

Nothin’ can stand in our way

“Magic” by Olivia Newton-John entered Billboard’s Hot 100 on May 24, the same day Maddox and Nystrom cast their respective spells on the Braves and Flyers. It would hit American Top 40’s airwaves on June 14. By then, the Mets would be reaching for the stars and we’d have trouble keeping our feet on the ground.

Ah, June 14. We’ll get to that soon enough, but let’s enjoy the ride that lifted us there for a moment or two. Let’s remember what it was like to take off toward a place that felt at once both familiar unattainable. Let’s linger at Shea for a week-and-a-half. Was it a real-life Xanadu (the mythical destination, not that awful movie)? Was it a slightly less suds-intensive version of Schaefer City (surely we were sitting pretty)? Or was it enough that it was Shea Stadium? Whatever it was, we hadn’t had that spirit there since 1969.

June 5: Swannie throws nine innings of one-run ball. Swannie, how we love you, dear old Swannie, but we and the Cardinals are tied at one. In the bottom of the inning, against George Frazier, Steve Henderson — remember that name — singles. He steals second. Joel Youngblood walks. Alex Treviño bunts and reaches. The bases are loaded. Doug Flynn is supposed to be up, but Joe Torre sends Mike Jorgensen in to pinch-hit. Jorgy singles to win the game. Jorgy, we love you, too!

June 6: We’re down, 1-0, in the second facing Bert Blyleven and the Pirates. By the time it’s the third, we’re up, 8-1, and Blyleven is no longer pitching. The defending world champions didn’t make any errors and we didn’t hit any home runs, but we scored eight runs in an inning en route to winning, 9-4. Olivia Newton-John may have been onto something.

June 7: The Pirates are up, at various times, by scores of 2-0, 4-1 and, most distressingly, 5-4, distressing because that last score is in the middle of the eleventh inning. Grant Jackson is on for the save. Instead, he grants us a stay of execution with a single and a walk. Chuck Tanner takes out Jackson and brings back Blyleven from the night before. Blyleven again gets his team in Dutch. Youngblood doubles home Treviño to tie the game and, after an intentional walk to Maddox, Doug Flynn is again pinch-hit for. Doug’s a Gold Glove second baseman for sure, but let’s say Torre knows his bat. The pinch-hitter is Ron Hodges, whose spirit we’ve had here since 1973. Ron awakens it long enough to single to right and bring home the winning run.

June 8: This time, in the first game of our Banner Day doubleheader, we jump in front. This time, Mike Easler hits two home runs to put us behind (like this is news?). Yet another time, we roar from behind. In the seventh, it’s Frank Taveras driving in Doug Flynn (sometimes Joe lets him hit) and Henderson brings home two more. In a Flushing flash, Ed Glynn comes on to put away the Pirates in the eighth and ninth. Put that on your banner, Buccos!

June 10: We didn’t sweep the aforementioned twinbill, but we had something more definitive in mind for the week ahead. The Los Angeles Dodgers came to town and got rained out on Monday. They’d get used to felling all wet. This night, a Tuesday, saw the former Brooklynites give back a four-run lead they’d built on three home runs in the fourth (Pat Zachry didn’t care for the power display and knocked down Ron Cey; we’ve all felt like knocking down Ron Cey at one point or another). The Mets evened matters up with three singles, two walks and two sac flies. And, perhaps, The Magic. It’s OK to invoke it in the early innings and long as some is left in store for later. In the bottom of the sixth, Doug Flynn drove in what proved to be the winning run of a 5-4 Met victory. Is it The Magic that got into Dougie’s Louisville Slugger all of a sudden or was it just hard-earned confidence from his manager?

“Magic?” Torre had rhetorically responded to reporters a couple of days before. “I’ve told you all before that’s just for public relations. I don’t care what they do upstairs. If we keep playing like this, that’s all I care about.”

June 11: The Mets keep playing like this. That’s all we care about. Treviño and Swan knock in runs with singles. Baker and Garvey get even with homers. We went to the tenth, loaded the bases and this is for the guys who cried when Jorgensen connected with Rick Sutcliffe’s last pitch. Tears of joy in Brooklyn and all nearby precincts these days, no doubt. Queens product Jorgy (a Frances Lewis graduate, you know) launched a grand slam to win the game, 6-2. Upstairs, downstairs, all round the Shea, everybody’s coming down with Mets fever.

June 12: Monday’s rainout was made up for on Thursday night. With no advance sale to speak of, you’d assume another MAGIC GARDEN sized crowd. But that’s only if you’d been snoozing since the middle of April. This was June. This was the month of The Magic. If you doubted it, you weren’t among the 19,501 — it would have sold out the real Garden — who witnessed the Mets taking it the Bums one more time. Of course the Mets fell behind (5-0). Of course the Mets came back (6-5). This is how The Magic works. Not quite 20,000 sounded like about three times that many. “The fans help,” Torre said. “I haven’t seen crowds like this since I came in here with another club.”

He ain’t seen nothing yet.

June 14: Flag Day. Wave it high. Wave it proud. That’s what we can imagine doing with a flag we’ll win someday. We imagine such a lofty goal and valuable piece of cloth because of nights like that of Saturday, June 14. It’s a date which will live in the opposite of infamy. I would bet all the nickels we no longer had to pay Lucy for counseling that we will remember June 14, 1980, for decades to come…that if I bring it up to you, I don’t know, some chilly spring day forty years from now when maybe things in the world aren’t going as we wish, its events will still feel as fresh and hopeful as it did when they transpired.

We talk a lot here about June 14, 1980. Why wouldn’t we? As this past season progressed, it was the cloud we floated on when maybe The Magic wasn’t so visible and it was the force that elevated us when we were down in the dumps. It was a more reliable conveyor of our upward aspirations than the escalators at Shea were (will those stupid things ever be fixed)? But because June 14, 1980, is our orange & blue-letter date, it’s worth diving back in yet again.