The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 30 July 2018 1:23 pm When they’re tired of a player, fans have been known to opine that they’ll drive him to the airport themselves. I’ve certainly said it a few times. Heck, I’ll give Jose Reyes a piggyback ride to LaGuardia if that will end the current farce. But what we don’t hear often enough is the opposite sentiment — a promise, say, to lie down on the runway if the Mets try to get rid of someone rumored to be on the move.

Someone like Zack Wheeler.

Wheeler has attracted plenty of scouts and rumors ahead of the trading deadline, and on Sunday he showed why he’s a hot commodity, scattering five hits and a walk over six innings. Which doesn’t capture how dominant he was: he was throwing strikes and working quickly and aggressively all day. Know how many times a Pirate saw a 2-0, 2-1, 3-0 or 3-1 count from Wheeler on Sunday?

Zero. That’s good.

The Mets being the Mets, they went out and backed Wheeler up with another zero: no offense, for which some credit should go to hulking hurler Joe Musgrove, who was pretty awesome himself as Wheeler’s opposite number. So Wheeler took care of things himself, burying a fifth-inning fastball that got too much plate in the right-field corner to chase Luis Guillorme home from first.

Wheeler departed after six on the right side of a skinny 1-0 lead, but Seth Lugo rebounded from Friday’s lousy outing to hold the fort, helped out by a good throw by Kevin Plawecki, whom I’d just taken to Twitter to declare myself officially sick of, and perhaps even willing to drive to the airport myself. (No piggyback rides, though — not for backup catchers.) With one out in the eighth, Starling Marte tried to steal first and was cut down by Plawecki, an erasure that held up under replay scrutiny and seemed to take the sap out of Gregory Polanco, who’d tormented us all series. Polanco, deprived of a runner in scoring position, swung at a ball out of the strike zone and was done.

That left the ninth in the hands of Anthony Swarzak and his train wreck of a season. But of late Swarzak’s been more like the pitcher the Mets thought enough of to give a two-year contract. He buzzed through the Pirates 1-2-3, and Wheeler’s 1-0 victory was secured.

If you’re scoring at home and have been for the last 49 years, you knew immediately that was the sixth time a Met pitcher had driven in the lone run in their own 1-0 win: the others to have done it are Jerry Koosman, Don Cardwell, Buzz Capra, Ray Sadecki and Nino Espinosa, with Koosman and Cardwell inflicting said indignity on these same Pirates (or, OK, on utterly different Pirates) in their respective portions of a Sept. 12, 1969 doubleheader. I remember that Koosman/Cardwell factoid from all the Miracle Mets insta-paperbacks I devoured as a kid; you know some veteran fan somewhere in Pittsburgh remembered it too on Sunday and went off, muttering, to clean out an already immaculate garage.

Anyway, Wheeler’s been good for some time, winning his last three starts to go to 5-6 — the sign of ace stuff in this Mets rotation. After losing two years to injury and one to accumulated rust, he looks like he’s figured out who he is, what he can do, and how he can do it consistently. Maybe it’s just my stubborn optimism at work again, but that strikes me as the kind of thing to build around rather than trade away.

* * *

Addendum: I’ll be at Tuesday night’s Mets-Nats game in D.C., and then seeing five more big-league games live over the next 10 days, part of a ballpark trip that will take me to Minneapolis, Milwaukee, both Chicago stadiums and Cincinnati. Will it be awesome, or the baseball equivalent of an ice-cream headache? Stay tuned!

by Greg Prince on 29 July 2018 12:46 pm The new Metropolitan standard of excellence by way of archaic statistics is Five Wins and Six Losses. That’s right, 5-6. Never mind the likes of 25-7, 19-10, 22-9, 24-4 or 20-6. Move over, Messrs. Seaver (those first three), Gooden and Dickey. You were Amazin’ in your respective Cy Young seasons, but there’s never been anything like what Jacob deGrom is doing.

Jacob deGrom is crafting a Cy Young-caliber season with increasingly Anthony Young-style results.

We all understand that AY pitched better than the 0-27 stretch that came to define his major league career. We also understand that 5-6 is laughable when attached to the year deGrom is producing, though none of us is producing the slightest chuckle that the best pitcher in professional baseball is saddled with what is commonly referred to as a losing record. The losing is primarily on the team for which deGrom labors. Jake is a winning pitcher. The Mets are allergic to his excellence.

In Pittsburgh on Saturday night, deGrom threw a shutout for five innings, which was, naturally, good enough to engage him in a tie with Trevor Williams. Trevor Williams might have been throwing an excellent game as well, but who can tell? Funny how the deGropposition is inevitably Jake’s equal. The Mets’ most imposing threat came in the fourth when they loaded the bases on two singles and a walk. With one out, Devin Mesoraco stepped up and grounded the first pitch he saw into a double play to end the imposition let alone the threat. Remember when we were congratulating one another on swiping Mesoraco from the Reds for that washed-up Matt Harvey?

DeGrom was so thrown off by his batterymate short-circuiting the closest thing the Mets had to a sure-thing rally that he threw a scoreless bottom of the fourth and then doubled in the fifth. He was still doing what he does in the sixth, striking out the first two Pirates on his docket to continue pushing his constant companion boulder uphill. That made it eight consecutive Buccos retired. But then — there’s always a “but then” — Jake allowed the softest of singles to Gregory Polanco. Polanco then stole second off erstwhile steal Mesoraco. Moments later, Colin Moran placed a ground ball out of the reach of Wilmer Flores and, bam, deGrom is down, 1-0.

Jake stayed in to hit in the seventh, because it was both the right thing to do for Jake or the right thing to do for the Mets. Why would you take Jake out of a game that he’s trailing, 1-0? Being Jake, he singled. Being the Mets, nothing came of it. Thus, it was back to the hill for the man forever trudging up one, and that’s where those Anthony Young vibes began to filter in. Not that deGrom didn’t deserve to keep pitching (who would you rather see?), but the experienced Mets fan knew the chance to reverse a nagging narrative trend had been definitively bypassed for the evening. In 1993, it meant we rooted for Young in the full if unspoken knowledge that something was eventually going to go wrong enough to place him beyond the reach of common winning decency. And in the seventh on Saturday night, deGrom cracked a little, allowing three more hits and two more runs. With two innings to go, the game was over, and by “game,” I mean the chance to keep deGrom’s record from dipping below .500. The eventual outcome, in which the Mets would lose, was already in the foregone conclusion category.

So Jacob deGrom, possessor of a 1.82 earned run average, is, to prevail ourselves of outmoded nomenclature, a 5-6 pitcher. It’s unlikely that if any of us had seen him walking across the Roberto Clemente Bridge after the game Saturday night, we would’ve said, in the spirit of the splendid Ted Williams documentary currently streaming at PBS.org, “There goes a 5-6 pitcher,” even “There goes the greatest 5-6 pitcher who ever lived.” We don’t think in those terms anymore, right? We all get the flaws related to the assignment of wins and losses to individual pitchers. We got it in theory a long time ago and, boy, do we get it in practice in 2018. We get it, yet we simultaneously find it hard to cope with such a pedestrian won-lost record linked to such a lofty four-month performance. We want the 1.82 pitcher to be something more — way more — than a 5-6 pitcher.

Yet if Jacob deGrom is a 5-6 pitcher, there must be something to be recommended from being a 5-6 pitcher. Actually, we didn’t need Jake to let us in on that statistical secret. Mets history is dotted with stars, legends and immortals who now share one undeniable commonality with deGrom: they, too, were 5-6 pitchers.

Eight different Mets have finished a season 5-6. Fingers crossed, deGrom’s season isn’t done (though you never can tell in these parts). But since we seem to be at the stage of his campaign where the best we can hope for out of the Mets is to furnish him a dozen no-decisions in his final twelve starts, let’s say our prospective MLB ERA champ winds up the year where he is in terms of wins and losses. Let’s say Jacob deGrom really is a 5-6 pitcher.

He would be in pretty good company. Granted, the members of the company weren’t necessarily at their best when they were 5-6, but they were still who they were despite compiling a record that lingered uncomfortably south of mediocrity.

Kevin Kobel went 5-6 for the 1978 Mets. At face, this is probably the least impressive example of a 5-6 Mets pitcher, but let’s not let that detract from the loyalty the scruffy Kobel elicited during his three-season tenure in Flushing. Inside the 1979 Mets Official Yearbook, the one whose discreet cover was the orange NY logo set against a blue warmup jacket, a page was devoted to letters from children (or adults with largely undeveloped handwriting). The first one printed came from wee Michael Settanni, and boy did he let us know who his guy was:

My favorite player is Kevin Kobel and he is a great player. I hope they are in first place. He is a great pitcher. He is a great batter to[o]. I am a met fan.

When you’ve got a kid like that in your corner, what do you need with run support? Kobel was something of a proto-deGrom forty seasons ago, compiling a 2.91 ERA in 108 innings pitched. The former Brewer lefty appeared in 32 games, starting eleven and completing one (one more than Jacob to date). In his starts, according to Baseball-Reference, the Mets scored 3.6 runs per 27 outs while Kobel was in the game, or the same as they did for Craig Swan, whose 2.43 ERA led the National League despite what was considered a rather wan won-lost record of 9-6. Nine-and-six would look pretty good on Jake a dozen starts from now, huh?

The Mets are scoring 2.9 runs per 27 outs while deGrom is in the game as a starter. All of them presumably came that one start in Colorado.

Charlie Williams went 5-6 for the 1971 Mets, pitching 31 times, nine of them starts. There was nothing inherent in his lone Met season to suggest greatness awaited on the righty’s horizon, except the following May he was traded to the Giants for Willie Mays. Nobody’s greater than Willie Mays. That oughta count as extra win on Charlie’s ledger.

Ron Darling went 5-6 for the 1991 Mets in 17 starts. His Met season indeed ended in July when he was traded to the Expos for Tim Burke, a previously effective closer whose skills were apparently confiscated by customs en route to Shea. Darling requires no introduction here, though the 1991 version is unrecognizable versus the younger, sharper righty who helped pitch the Mets to the postseason twice and generally excelled throughout the 1980s. This was the beginning of the period of 1990s Mets baseball Ronnie regularly claims no memory of during SNY telecasts despite taking the ball from Buddy Harrelson those 17 times. He would later rediscover his abilities for a division-winning club in Oakland. Burke, not so incidentally, was a Cy Young-level human being. Pitching isn’t the only thing by which we should recall pitchers.

Pedro Martinez went 5-6 for the 2008 Mets. Seven summers later he was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Pedro was ticketed for Cooperstown well before he signed a four-year contract with the Mets in December 2004. The fourth year was considered extravagant, but worth it to have him in 2005. In 2005, when Pedro was still regularly flashing Hall of Fame form, who was worried about 2008? In 2008, 33-year-old Pedro struggled amid injuries and the ravages of age, though now and again reminded you he was Pedro Martinez. His final start as a Met was a lesson in grit and determination. He kept the Mets on life support as they pursued one final postseason appointment for Shea, leaving the game of September 25 in the seventh, two Cubs on base, nobody out, scored tied at three. After Jerry Manuel removed him, we had the presence of mind on this raw, rainy night to stand and applaud for all he did in his four seasons as a Met and he had the presence of mind to acknowledge our appreciation of him, pointing at every slice of the stands as he returned to the dugout. It was such a beautiful moment.

Then Ricardo Rincon came on and gave up a three-run homer to Micah Hoffpaiur, sticking Pedro with two extra earned runs and reminding us how hard it is to get to the end of a season, a contract and a ballpark. Fortunately, the Mets rallied and forged their last Shea walkoff in the ninth. Unfortunately, there was no postseason. Had there been a one-game playoff for the Wild Card, Pedro was probably going to pitch it. In light of the 5.61 ERA he posted in 20 starts (and the Rinconian relievers who were forever warming up behind him), I don’t know how that would have gone. But I’d have taken my chances with a diminished Pedro Martinez over most anybody else.

Carlos Torres went 5-6 for the 2015 Mets, pitching 59 games exclusively out of the bullpen. Torres’s three seasons as a Met, encompassing a couple of handfuls of spot starts, were the essence of a 5-6 pitcher, if not the one we’re presently pulling for. Torres tended to pitch well when you weren’t paying attention and blow games when you were. That was what made me think of him as Carlos Tsuris. Sadly, an injury kept him from being part of the pen of which he’d been such a staple from 2013 forward when the Mets finally visited October for real, but Carlos did enjoy one signature moment while the Mets pushed toward their pennant. On August 27, working in the tenth at Citizens Bank Park, Torres’s foot fielded a shot off Jeff Francoeur’s bat that bounded into the vicinity of first baseman Daniel Murphy. Murph being Murph — and this being 2015 — it resulted in one of the most scintillating outs of the season. Murph grabbed for it, flung it to first sans glance on the slight chance that somebody would be there to retrieve it on the fly…which Torres was. Francoeur went down and, three innings later, so did the Phillies.

The winning run that wild Thursday night was scored by Torres, too, Carlos having led off the thirteenth with a single. It was great batting that a now older Michael Settanni would have appreciated.

David Cone went 5-6 for the 1987 Mets, but there was no mistaking that, unlike Devin Mesoraco, he represented a long-term steal for the Mets. The Mets used to pull heists on unsuspecting GMs all the time, and prior to their most recent championship-defending season, this one was a doozy. The Royals needed a catcher. They wanted Ed Hearn, able backup to Gary Carter in 1986. They were willing to give up this promising righthander with the unusual delivery (Laredo, we’d learn it as) in exchange. We wouldn’t express such a sentiment come November of 2015, but thanks Royals! Cone was not yet a skilled batsman or at least bunter in his first Met season. We lost him for two-and-a-half months when he broke a finger while attempting to bunt in late May. But young David returned and contributed to the Mets’ ultimately doomed quest to repeat. Five-and-Six didn’t describe how good Coney was about to become. Twenty-and-Three in 1988 did the job much better.

Sid Fernandez went 5-6 for the 1993 Mets, a team that rarely went 5-6 in any isolated eleven-game span. Sid missed three months while the 1993 Mets were leaving their mark on the darkest recesses of our souls, but when he returned from injury in late July, he was essentially the same El Sid who was a featured fifth of all those great contending Met rotations of yore. The contending was only a memory for the Mets of 1993, but Sid was still bringing it in that often unhittable, intermittently frustrating fashion of his. After tossing seven innings of two-hit ball at Joe Robbie Stadium in the next-to-last game of that sullen season, Fernandez lowered his ERA to 2.93…and raised his record to 5-6. Next time Sid put his left arm to good use, it was as a Baltimore Oriole.

Tug McGraw went 5-6 for the 1973 Mets. I don’t know that we can say Jacob deGrom has given us the greatest 5-6 season in Mets history as long as we know Tug McGraw went 5-6 for the 1973 Mets. Tug McGraw was the embodiment of the 1973 Mets, and little in life is better than recalling the 1973 Mets. Tug, of course, was mostly a reliever, though he did take two starts in ’73, mostly out of desperation on Yogi Berra’s part because Tug was having such a dismal season relieving. As of August 20, Tug was an 0-6 pitcher no matter when he entered a game. Not that relievers’ won-lost records amount to much in the way of a metric, but McGraw was consistently awful and the Mets were stuck in last place.

But you know what the screwballer said — You Gotta Believe. Tug did and we did and, in a veritable blink, Tug won five in a row, saved a dozen (without blowing a single game) and the 82-79 1973 Mets, following the lead of their 5-6 fireman, Believed their way to the National League flag. Nineteen-and-Ten Seaver was rightly voted that year’s Cy Young, but Tug won a place in our hearts that transcends the glitziest of awards not to the mention the drabbest of statistics.

Jake has already secured a spot of that nature with us. Sure would be nice to see the Mets bump him up beyond .500 before this season is over, though.

Yup, sure would.

by Jason Fry on 28 July 2018 12:39 pm On Friday, in rapid succession, the Mets lost an interesting player and an interesting ballgame.

The player, of course, was Asdrubal Cabrera, now a member of the Philadelphia Phillies. More on him in a bit.

The ballgame, hmm. It wasn’t exactly a showcase for baseball, as at times neither team looked like it had any idea what it was doing out there. But it was kind of fun nonetheless, with Mets fans offered plenty of chances to size up new players and Pirates fans given plenty of chances to figure out if their team is great, terrible or somewhere in between.

Honestly, this was a game the Mets should have been out of early. Jason Vargas‘s line looks OK but was anything but: he was horrible, as he’s frankly been all year. He gave up a home run to David Freese in the second to bring the Pirates within a run, then loaded the bases with two outs in the fourth and hung a curve to Jordy Mercer. It was a meatball, all but arriving with a polite note to be turned into a souvenir, but Mercer missed it, lining out to Michael Conforto in left. Vargas — who at least is self-aware — knew it, too; SNY cameras caught him rolling his eyes as he walked off the mound, simultaneously appalled at what he’d done and amused that the baseball gods had given him a reprieve.

The stay of execution was temporary. Mickey Callaway let Vargas lead off the fifth with 73 pitches thrown, few of them sharp. In the bottom of the fifth, Vargas got Ivan Nova, but lost Jordan Luplow on an eight-pitch walk and departed for Seth Lugo, who arrived bearing a curveball he couldn’t command, a flat slider and probably a feeling of foreboding. Lugo didn’t get the call on close pitches to Elias Diaz with two outs, started Freese out 0-2, but then couldn’t get him to fish. Lugo went to the fastball, left it in the middle of the plate, and the Pirates led 4-3.

The Mets responded by loading the bases with nobody out, prompting me to sardonically ask Emily how many runs she thought they’d get: zero or one? The answer was one, and it was a near-thing, as Conforto scampered home on a horrific throw from Luplow that was so bad it almost turned into a Pachinko-style out at the plate. Then it was Reliever Roulette, which the Mets lost, though they did at least start using the young hurlers they’d called up and then decided to let gather dust and cobwebs in the bullpen. Last I checked, that wasn’t the optimal way to keep pitchers sharp, but what do I know.

Even the failure was interesting, though: in the fatal bottom of the ninth, Tim Peterson somehow managed to allow four baserunners on six pitches, which you have to admit is efficiency of a sort. One of those baserunners was an intentional walk, which would have made that combination of pitches and outcomes impossible not so long ago; in the era of the abracadabra walk it was still fairly unlikely. The last pitch, inevitably, was to Freese, who drove it over the head of an already-clubhouse-bound Jose Bautista, and that was that.

The Mets played a man short because Cabrera was dispatched to Philadelphia late in the afternoon in exchange for a huge, raw Double-A starter named Franklyn Kilome. Immediate reactions to the deal were far kinder than the response to the Jeurys Familia trade, in which the general consensus was that the Mets had traded a faded but still useful closer for roster fillers, slot money and (cough cough) cash back in the Wilpons’ pockets. Kilome has a beastly fastball he sometimes leaves up to get whacked, a plus curveball and control problems, which is a long-winded way of saying he’s a young pitcher in Double-A. Still, not a bad return on two months of a free agent to be.

As for that free agent to be, Asdrubal Cabrera will now play alongside Odubel Herrera, a combination that’s always entertained me and should have Phillies’ A/V guys preparing their parodies of “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off.” We are left to miss him except for our nine games remaining with Philadelphia, ample time for Cabrera to beat our heads in.

Which I have no doubt he’ll do. Cabrera had superb baseball instincts and a frankly ridiculous amount of grit, playing through far more injuries and nagging hurts than we ever knew about and still handling both second and third capably. He kicked up a fuss about being moved off short, it’s true, but if any of us had the misfortune to be Mets employees I have a feeling we’d all be kicking up far more fusses than he did.

If a Mets game was coming down to a key at-bat, Cabrera was the guy I hoped to see at the plate. When he faltered or failed in those situations, he turned into the position-player equivalent of Al Leiter: any rancor you wanted to direct at him quickly disappeared because Cabrera was already angrier with himself than you could possibly be. Sometimes this made me laugh; sometimes this made me laugh while being mildly worried about him. Seriously, cartoon characters with steam whistling out of their ears and noses were slightly less over the top about their rage than Cabrera with a good boil on.

But enough about failures. I wanted Cabrera at the plate because there was a good chance he’d succeed — as he did in crafting one of the Mets’ indelible Citi Field moments, the September walk-off homer against his future employers that keyed the team’s unlikely march to a 2016 play-in game.

Greg had the recap of that night, which you can read here. I wound up watching it over beers (so many beers) at Foley’s, with an old friend in town and a guy at the next table who was making his first trip to Citi Field the next night and had a million questions about the park, the fans, the atmosphere, and everything else.

The Mets blew a 4-3 lead in the eighth, with Addison Reed surrendering a three-run homer to Maikel Franco, but tied it in the ninth on a two-run shot by Jose Reyes. They then gave up two more runs in the 11th, but kept grinding along, putting two men on against Edubray Ramos. With one out, Cabrera connected. He knew it was gone before anyone else on the planet did, flinging his bat away and thrusting both arms skyward. Cut to Foley’s, and one overserved blogger flinging his own arms skyward in happy disbelief. Future Citi Field attendees were hugged, impromptu dances were exhibited, exclamations of amazement were made, beer may possibly have been spilled, and who knows what else.

Cabrera’s reaction and Gary Cohen’s double OUTTA HERE! will be replayed forever in Met Land, and justifiably so, but my favorite part of that highlight comes a moment later. It’s the sight of all the other Mets scurrying from the dugout to home plate, hurrying to get there and form the welcoming committee — but Cabrera, at least for the moment, is going the other way, his pace a moderate trot. A long night’s labors are behind him and a celebration awaits. But these next few seconds are Cabrera’s alone, and he’s going to use them to quietly savor a job well done.

by Greg Prince on 27 July 2018 4:40 am Such a messy game for such a tidy milestone, but given that the biggest mess of runs landed decisively on the Mets’ side of the box score, of course we’ll accept it without complaint. We do so little without complaint these days. What Mets fan could possibly complain about a 12-6 Mets romp over the Pirates?

The Wilpons still own the team, so that might get you airing your grievances, which is your prerogative, but I didn’t become a Mets fan to root for or against the owners. I rooted for the Mets to win as soon as I got to know them in 1969 and I still do in 2018. Thursday night in Pittsburgh, I rooted for…

• Steven Matz to shake off some early difficulties…which he did, going six innings that got better as they got later, culminating in a surprisingly reassuring four-run outing garnished by nine strikeouts, including six of the called variety;

• Asdrubal Cabrera to deliver a powerful potential swan song as the trade deadline nears…which he did, via two runs, three hits, four ribbies and a homer that climbed higher than the 21-foot wall that graces right field at PNC Park;

• Amed Rosario to continue to sizzle…which he did with two more hits, bringing his recent offensive output to 8-for-22 and, at last, revealing what it was that had us panting for his promotion a year ago at this moment;

• And Jeff McNeil to continue to get acclimated to big league surroundings…which will doubtlessly take a little more doing (witness Rosario’s stubbornly incremental progress to date). McNeil started at third for the first time in a Mets career that commenced Tuesday. The first ball hit toward him eluded him completely. The first time he was on second, he raced to third despite Jose Bautista having very recently slid into it and not showing any intention of leaving it. Rookies, even the 26-year-old late bloomers who were tearing up every level of the minors, will be rookies. Jeff didn’t have jitters with the bat, though. The relatively young man singled once, walked once, was intentionally passed once and Nimmo’d once (a.k.a. was pinged by a pitch). He’s not a flop. He’s not a star. He’s Jeff McNeil, New York Met, and he just got here. May he have plenty of opportunity to let us discover what he’s all about.

So, basically, I got everything I was pulling for, and I would guess you did, too. OK, maybe not everything. Twelve runs, fourteen hits and a three-game winning streak, no matter how satisfying all of it is, doesn’t seem primed to suddenly spur the current owners to clear a path for successors. Or does it? Maybe a 43-57 juggernaut on a long-awaited upswing is more attractive to some mysterious deep-pocketed big shot than a 42-58 sad sack would have been. Perhaps now that Jeff McNeil is finally getting a long look, billionaire sportsmen types will be lining up to bid any minute now.

If you can bear to leave that fantasy to fester, I would direct your attention to the Mets’ record as stated in the preceding paragraph. Do the math and you’ll note we just passed the hundred-game mark. Tidy, huh? The number is round and the arithmetic is easy. At no other juncture between now and Closing Day will calculating your team’s winning percentage, unless the number of wins equals the number of losses, be such a breeze. One-hundred games means you take the wins, you bracket them with a decimal point and a zero and you have your answer. For example, the 2018 Mets have 43 wins after 100 games and are thus a .430 baseball club.

Aren’t you glad you could figure that out so quickly?

One-hundred games also provides a pause to gain one’s bearings if the bearings don’t already speak for themselves. Sadly, 2018’s bearings have said most of what they need to say to such an extent that “tell your statistics to shut up” is a perfectly polite response when they begin to clear their throat. You don’t need to be a math maven to know a .430 winning percentage doesn’t scream much in the way off imminent possibilities like they oughta be. We wouldn’t be talking dealing Cabrera if there was anything utterly unknown about the fate of this season. We probably wouldn’t be greeting McNeil, at least under these circumstances. An enlightened organization amid a playoff push might have recognized the thunder lurking in his knobless bat and put him to good use already, but we’ll never know. If our sad bearings hadn’t made themselves plenty apparent, Metsopotamia’s evergreen topic of What Will Make the Wilpons Sell? wouldn’t have returned to the fore as the current season’s odometer was reaching triple-digits.

The best and worst 100-game records in Mets history will not surprise you. The best was 1986’s — by a lot. In the year of teamwork that made the dream work, the Mets were, at this stage of their season, 68-32. That’s eight games better than any other Met team (1988) has been after 100 games. The worst was 1962’s — by enough. In the year when it wasn’t obvious anybody here could play this game, the Mets were, at this stage of their season, 26-74. That’s four games worse than any other Met team (1964) has been after 100 games.

Despite the surge that has presumably lifted our spirits these past three days, the 2018 Mets are closer to overhearing the conversation for worst 100-game marks than best. We are at present one game ahead of the pace set by the 42-58 2003 Mets…or one game behind our predecessors from 15 years ago if you frame what remains of our season as an epic struggle to determine the worst Met team of the 21st century. Also, 43-57 ties us with our 1978 and 1979 forebears. In case you’re seeking a silver lining, after 1978 and 1979, we got new owners.

What interested me most when I dug into The Mets After A Hundred Games was gleaning the point hope tends to disappear. Understanding that you’d need to know where the Mets stood in the standings in a given year to form a truly telling snapshot, most times a hundred-game record will communicate the essence of what a fan feels. When the Mets were 59-41 on five separate occasions (1984, 1985, 1990, 1999, 2006), you felt alive. This thing is there for taking, let’s get after it! When the Mets were 53-47 on four other occasions (1975, 1989, 2008, 2016), you felt anxious. We’re in this thing, but we can’t lose ground — oh, for cryin’ out loud, don’t tell me the Pirates/Cubs/Phillies/field won again. When the Mets are 43-57…well, you know exactly how that feels.

A little above .500 after 100 is where you have to start to rely on faith. Twice the Mets have been 52-48: 2002 and 2015. One of those seasons descended into a nightmare. The other ended in the World Series. Faith can be fickle that way. The 51-49 crews of 1976, 2005 and 2010 were coming at it from three distinct angles. The ’76 Mets were light years in back of Philadelphia (it was the Bicentennial, we had to let ’em have that one), so our record was mostly bookkeeping. The 2010 Mets were in full retreat from their surprisingly good first half, so winning more than losing seemed a temporary condition. The 2005 Mets, though, legitimately orbited the Wild Card race and, perhaps more vitally, were re-establishing their credibility as a franchise (something we seem to have to do every few seasons). 51-49 felt pretty, pretty good thirteen years ago.

There’s been only one literal 50-50 proposition in Mets history: the 2011 Mets. Their even-Steven 100-game mark coincided with the briefest of leaps of faith that maybe, just maybe, if everything clicked and enough other teams in front of them fell apart…nah, that wasn’t gonna happen, and it didn’t. Respectability was fleeting. Selling was on the agenda. Next thing you knew, there we were trading Beltran for Wheeler and waving .500 goodbye.

Twenty-nine Mets teams have sat below .500 after 100 games (not counting split-season 1981, which just loves getting the special “not counting” treatment in these retrospectives). Barring a miracle that would consign 1969 (56-44 at 100, incidentally) to asterisk status, 2018 will be among the twenty-eight certain to wrap up its business no later than early October. Only one sub-.500 Mets club at the hundred-game mark went to the playoffs. You gotta believe it was the 1973 edition, easily dismissed at 44-56 — one lousy game better than we are now — and in last place. I’d say “buried in last place,” but the nine-and-a-half-game margin between them and first-place St. Louis paled in comparison to how far MLB’s other cellar-dwellers dwelled from the tops of their respective divisions. The Rangers were 17½ in back of the Royals in the AL West; the Indians were 20 behind the Yankees in the AL East; and the Padres languished 30½ games from the Dodgers in the NL West.

None of the first-place teams at this interval of the 1973 schedule won its division, but only the Cardinals let the losers in last relish the last laugh. (Ha!)

Nineteen Seventy-Three’s run to the National League pennant is the reason we seek every possible entrée into dreaming dreams that barely qualify as remotely statistically plausible. All those other sub-.500 records after 100 games are the evidence that such crazy dreams rarely come true. The odds are 28:1 against.

Yet we dream. We dream with tangible degrees of conviction in the face of better judgment at 49-51 (1980, 1992, 2009). We dream infinitesimally despite mostly grasping reality at 48-52 (1994, 2004, 2012). We dream ever, ever so slightly and delusionally at 47-53 (1968, 1996, 2014, 2017). We probably nod off unimpeded by bizarre dreams of contention once we dip to 46-54, as we did in 2013, but you know, in 1973 we were 44-56…

In 2018, we’re not even that. Sixty-two games to go.

by Jason Fry on 26 July 2018 11:50 am In a lost season, you appreciate the little things. Sometimes because they might grow into big things, and sometimes just for themselves.

You appreciate two-out singles by Phillip Evans (yet another victim of the Great Jose Reyes Fiasco) and Amed Rosario to tie the game and then give the Mets a two-run lead.

You appreciate that the timing of those hits delivered a first big-league win for Corey Oswalt, who’d been removed either because his hand was sore or because that’s what Mickey Callaway‘s Big Book o’ Managing told him must to be done. (Any and all explanations by the skipper are automatically regarded with suspicion.) That win came after a string of outings in which Oswalt deserved such a reward but one wasn’t forthcoming, because the Mets.

You appreciate a game marked by fine defense on both sides. There was Jose Bautista making a nifty running grab (his second fine play in as many days) in right to save one run (and maybe two) in the fourth. There was Bautista, again, alertly short-circuiting the San Diego fifth by nabbing pitcher Clayton Richard at second on a dunker in front of him. There was Freddy Galvis (temporarily) rescuing Richard in the fifth on an errant throw to second which he converted to a nifty spin and tag of Kevin Plawecki.

And hey, there was Brandon Nimmo making a marvelous leaping catch to take away a home run from Austin Hedges, only to have the replay meanies correctly note that Nimmo had trapped it off the back wall. Nimmo sold it, too — a little instinctive leftover from the days in which calls were made by umpires and reviews belonged to the historical record and what-if fiction.

All of that was good fun as the Mets won a matinee and — gasp! — a series, their first series win since May 20, when they were 23-19 and we were still trying to convince ourselves that a headlong plummet was a mere stumble.

But as that last sentence indicates, the problem with appreciating the little things is that the bigger things keep rudely shoving themselves into the picture.

Like Yoenis Cespedes being out until … well, it’s the Mets, so let’s not even speculate, but there are two heel surgeries involved and the talk right now is May. Perhaps we’d be better off asking, “Which May?” And this inevitable pass has been arrived at via the usual Metsian Stupid Watergate way: waiting too long to put a player on the DL, grousing about his inability to come off of it, anonymously insinuating said player is soft, navigating second and third opinions amid palpable mistrust between player and organization, sending flunkies out to prevaricate, and finally arriving at the dreary conclusion. This has been happening through multiple general managers and training staffs, so you don’t need Sherlock Holmes to figure out where the real problem lies.

Or like the Mets being likely to look different when they return from their current road trip after the trading deadline. Normally that would be a little thing to be glad about — the rot of a dead team is best turned into fertilizer as early as possible. But the Mets’ shamefully paltry return on Jeurys Familia makes this potential good little thing more likely to be another bad big thing. The Wilpons are playing their usual game of seeking salary relief rather than prospects, and meddling with an already ill-advised front-office arrangement. Which is a recipe for minimizing the return on useful pieces, and the reverse of the process that a competently run organization would follow.

Should the Mets think bigger and trade some combination of Zack Wheeler, Steven Matz, and Jacob deGrom? In theory, absolutely — 15 games under .500 is excellent evidence that some other plan should be pursued. But that theory presumes the Mets would get something decent back in such a deal or deals. The 2017 deadline crop and the Familia trade strongly suggest they’d instead maneuver themselves into securing a pittance — the inevitable money back in the Wilpons’ pockets and a bunch of raw lottery-ticket bullpen arms that not even a connoisseur of agate-type transactions could get excited about. If you’re going to trade key pieces of a young, cost-controlled rotation, you better get a lot more than middle-relief maybes. Because if you don’t, you’ve all but assured there won’t be big things to appreciate any time soon.

by Jason Fry on 25 July 2018 10:45 am It was, admittedly, one of those Everything Has to Go Perfectly ideas: Emily and I were landing at JFK a little after 4, taking the subway home to drop our luggage, then turning around and getting back on the subway to meet her father and our niece at Citi Field to see the Mets take on the Padres.

Everything Has to Go Perfectly plans do occasionally work, even in New York City, and when they do you feel like you’re at the head of your own triumphant parade. But not this time. The plane was late leaving Logan, sat on the tarmac at JFK while a gate was cleared, the A train was slow to come, the A train was slow to advance, the 7 train was a local, the 7 train inched into Mets-Willets Point at the end of its journey, and then — inexplicable and maddening — the 7 train sat at our destination, doors stubbornly closed, for a good three minutes or so.

By which point it was 7:40 or so and the only gate taking mobile tickets was the rotunda, a Mets customer-service change I’d forgotten. We got in through McFadden’s using the tickets I’d printed as backups (that’s a genuine customer-service improvement, at least), but it took a while and by the time I joined a long line for tacos and realized the kitchen was both understaffed and moving with the urgency of a sweet summer stroll, I was thoroughly annoyed.

What made it worse was I’d glimpsed the score during our trudge around the stadium and seen a 3. The Mets were already down 3-0. Fantastic.

And then, in the taco line, everything changed.

I saw Wil Myers single and Manuel Margot slide into Devin Mesoraco at home, his foot pushed off home by Mesoraco’s knee. Out, singled the ump. Mesoraco, aware of replay-era baseball’s uncertainties, fired down to third to nab Carlos Asuaje as he sauntered into the base like he was auditioning for Citi Field food prep. The first replay showed me and the surrounding Mets fans that Margot had pretty clearly been safe. But what to do with Asuaje? Declare him out with a lecture about assumptions, or replant him on an unoccupied base given that he might have considered the inning over?

While the umps huddled, my fellow taco seekers and I did the same. After a brief exchange of views, our conclusion was unanimous: fairness dictated Margot be called safe and Asuaje out, ending the inning. Which, miraculously, was what happened.

The tacos were still being prepared by too few people moving too slowly. But my impromptu seminar with fellow Mets fans had chased away my being annoyed by travel bobbles and Wilponian customer service. The world is a better place when the people around you care about a weird play in the early innings of a meaningless game between also-ran teams and the importance of Getting It Right.

Oh, and I’d noticed something else: that crooked number I’d spotted wasn’t against the Mets, but for them. Rather than being 5-0 Padres, it was 3-2 Mets. That made me feel better too.

As my life’s Waiting for Tacos period finally reached its conclusion, the crowd roared. Michael Conforto had driven a two-run homer over the fence below where my party was waiting in the second row of the Coca-Cola Corner. 5-2 Mets. I arrived and found the night had turned breezy and coolish if not exactly cool — the front that had threatened to rain on the game had instead knocked down some of the humidity.

Things had turned, and the rest of the game was calm and soothing. The Mets added another run on a Amed Rosario triple and an Asdrubal Cabrera single, a combination likely to soon become impossible and so best enjoyed while still available. Zack Wheeler, having emerged from his bumpy inning intact, pushed through seven innings of fine work. Before the top of each inning, Jose Bautista tossed the ball he’d used to warm up into our sections, serving as his own one-man Pepsi Party Patrol or whatever its new name is.

I realized that my having been absent from the premises since last April (!!!) meant I was getting my first in-person look at the likes of Rosario, Brandon Nimmo and other Met stalwarts. And Jeff McNeil appeared, to my surprise — he’d been recalled while I was piloting rental cars and being piloted on airplanes. McNeil, as if making up for lost Reyesian time, liked the look of the first pitch he saw as a big-leaguer, served it into center field, and tried and failed to look cool about things while he stood on first and the ball was removed from play. If I watch baseball until I’m 99, I will never get tired of that little ritual.

Oh, and the game was concluded in a crisp 2 1/2 hours or so, allowing us to wind our way back along the 7 and fall into bed in Brooklyn by a reasonable hour.

Maybe this isn’t the greatest season in Mets history, but it was a pretty fun night. Maybe I ought to do this more often.

by Greg Prince on 24 July 2018 12:46 pm On a night when the Daily News didn’t send a reporter to Citi Field to cover the Mets, the Mets didn’t necessarily make news worth covering. That is if you subscribe to the theory that mundane “dog bites man” and “Mets bite in general” events don’t much amount to news.

You wouldn’t want to be the man who gets bitten by that dog, though, and right now you wouldn’t go out of your way to link your happiness to the fate of this baseball team unless the habit of tuning into them was hammered into you at an early age. Those of us who tuned in decades ago don’t know how to tune out. The best we could do on a deathly quiet night like Monday was watch from a distance with diminishing interest.

Which was more than any of the few reporters still associated with the News was directed to do.

Nevertheless, there’s always something to write about with this team, no matter how little of it is flattering. On those nights when the grind of constant losing got to him, Casey Stengel, the essence of good copy, didn’t hesitate to refer to the Mets he was guiding deeper into the basement as “a fraud”. The description, within the context he offered it, still seems to fit. The Mets as currently constituted are indeed a fraud. Or would that be “frauds” plural? I’d ask a copy editor at the News to weigh in on proper usage, but thanks to cold corporate calculus, the desk is suddenly shorthanded.

The decidely non-fraudulent Jacob deGrom pitched Monday night, which is usually cause for a heightened sense of engagement, even in the latter half of 2018 when we already know the story of the season as a whole and can pretty much guess the outcome of any given contest. DeGrom was very, very good. Unfortunately he dared to allow some Padres to hit the ball just enough for his defense to undermine him — as if his offense wasn’t handling that task with aplomb. Three runs were scored by San Diego in eight innings en route to their 3-2 victory over the best pitcher in professional baseball. Two of them were earned. Only one of them wasn’t helped along by a Met miscue. The league-leading ERA that began the evening at 1.68 finished it at 1.71. So, yeah, Jake was slightly off his game.

There are other sets of numbers that shed light on the dichotomy between deGrom’s brilliance and the Mets’ dimness when the former hurls his heart out for the latter. I will conscientiously object to disseminating them here. It’s too depressing. As if watching the Mets play dead on a Monday night wasn’t already depressing. As if absorbing the fate of the Daily News wasn’t already depressing. The Mets at least sometimes win one when not preoccupied by depressing defeats, unprecedented disabled list assignments and tortured medical explanations. The News has been cast by its ownership into apparent utter irrelevance. I say “apparent” because it’s not like I’m running out to buy a copy to confirm that it’s something not worth buying let alone reading.

True, I wasn’t running out to buy a copy in the days immediately preceding yesterday, before half of the editorial staff, including most of the sports department, was dismissed by an entity unimpressed by the concept of journalism. The News could have staffed last night’s game with the reincarnations of Jack Lang, Phil Pepe and a pre-embitterment Dick Young and I wasn’t dropping a buck-fifty at any newsstand for it. Same for the print editions of its rivals. I stopped buying the papers every day in 2007, which made me a late unadopter in the scheme of media consumption patterns. Before then, I was a loyal customer. A habitual customer, you could say. Like the Mets, the newspaper habit was hammered into me at an impressionable age. My dad bought the News mostly on Sundays, mostly for the comics. I adored the whole package and began seeking it out on weekdays. As Curtis Granderson might have posited, true New Yorkers read the News. Via my distribution of coins, I was determined to be one of them.

Most all of us hold dear some gauzy childhood memory of the connection between ourselves and a newspaper. That explains to a great extent how we became Mets fans who love to read. But it doesn’t say anything about continuing to buy newspapers. I stopped with the News and its peers because I realized I was getting what I needed via computer, whether it was posted by the newspapers themselves or by others conveniently aggregating on their behalf. Besides, I was paying for an Internet connection. I had only so many coins to distribute. Eventually I’d ante up for a digital Times subscription and, recently, for access to The Athletic, which has been a boon for sports coverage, national, regional and local. Sometimes I see tweets from sports fans aghast that they can’t read Ken Rosenthal’s freshest column for free. I guess they’re not old enough to remember the candy store owner who burned holes through you with his eyes to remind you he wasn’t running a library here.

Well into the 2010s, when Stephanie would go out for drug items and bagels on Sunday mornings, she’d bring me back the papers because we’d always bought the papers on Sunday. I never asked her not to continue purchasing them and I cherished the ritual of digging into her CVS bag and fishing them out. Around 2015, I told her don’t bother with the Times anymore, we’re already paying for it online; I read most of these stories three days ago. But she kept picking up Newsday and the News. They were less expensive than the Times; Newsday had enough local reporting to make having a copy seem worthwhile (even though our cable/Internet provider, which owns Newsday, magnanimously lowers the paper’s dot-com paywall as part of its Silver-level service); and the News…the News was what instinctively lit up Sunday mornings for me for as long as I could remember. I’d grab the comics as soon as my dad was done with them. I’d read every column inch in the sports section. I formed a portrait of what the city and its citizens were all about from that weekly foray into New York’s Picture Newspaper.

That was the Sunday News to me when I was a kid. As an adult nearly half-a-century later, it was a thin curio. I already knew the sports and I didn’t keep up with the comics. Everything else it printed I had gleaned the essence of elsewhere. One Sunday morning last summer, when we were out early, I made a point of picking up the News and Newsday because it felt wrong not to have them on hand. Seven days later, I told Stephanie not to bother with those papers anymore, either. I still reflexively look in the CVS bag for them, kind of missing them in ritual, not missing them at all in reality.

Despite no longer being their customer, I definitely miss the idea of the News covering everything the News has always covered, last night’s Mets game included. Sometimes I’d click on their game stories, features and columns and be enlightened. It was often compelling as content and it was surely comforting that it was there. At some point, however, seeking it out — never mind paying for it — stopped being habit for me. I’m surely not the only one who can say that.

by Greg Prince on 23 July 2018 4:05 pm Should there be a rain delay (or a pause for injury) tonight during the Mets-Padres game, flip over to your PBS affiliate at 9 o’clock EDT. Whatever the state of the skies, set your DVR accordingly, either for its premiere airing or later in the week when it’s scheduled to be rerun at some off hour, because you should definitely catch the latest installment of American Masters, Ted Williams: The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived. If you’re a baseball fan, you already kind of know the story, but when you watch this crisply paced one-hour film, you will be glad you got to know it in detail. You’ll meet Williams the Mexican-American, Williams the young San Diegan, Williams the toast of New England, Williams the war hero, Williams who didn’t doff his cap when his playing days were over, Williams who fished like he hit and Williams who hit like nobody else. Even if his career was before your time, you’ll understand why his story needed to be told anew in the 21st century.

And, to be parochial about it, you should see what a Mets fan can do on PBS, because this edition of American Masters was directed by Nick Davis, not only a talented auteur but a lover of all things orange and blue (including this blog). Nick did a great job incorporating modern touches into a classic baseball tale and does all Mets fans proud as he spotlights the quintessential Red Sox legend.

Even if he wasn’t a Mets fan, Nick’s movie is worth watching. It’s that much better because he’s one of us. Seriously, check it out.

by Greg Prince on 22 July 2018 3:49 pm To borrow a phrase favored by Josh Lewin, what did we learn on Saturday afternoon watching the Mets lose in the Bronx, other than Saturday afternoon Subway Series conflicts have diminished in appeal since Matt Franco was in fullest bloom?

We learned the phrase “den Dekker” is Dutch for “not Lagares”.

This is linguistic clarification gleaned after the Mets center fielder of the moment lost three fourth-inning fly balls in translation. Mets fans with memories longer than a Yankee Stadium short porch home run will recall Matt den Dekker was originally cast as the can’t miss defensive whiz in the attempted 2013 reboot of the Mets as a competitive baseball entity. Turned out den Dekker did miss — loads of time, due to the injury which opened the gates for Lagares to take his projected Gold Glove role — and could miss, specifically a trio of not easy yet not impossible chances hit in his general direction Saturday. They went for a triple, a double and a single, but when measured by cringe factor, the first was a boot and the next two were reboots. Given that Matt is 0-for-17 since his surprise recall from obscurity, one wonders what his particular major league acumen is at present. Someday, some kind soul might rediscover Matt den Dekker and lovingly recall him as the Billy Murphy of his time. That day is not today.

We learned Ron Hunt’s spiritual grandson Brandon Nimmo owns a record that somehow wasn’t Ron Hunt’s when the day began.

Brandon, when not leading with his grin, has spent 2018 putting his body into enough pitches to gain first base without swinging or taking. Standard-issue players only get hit incidentally. Brandon is clearly custom-made. By uncomplainingly accepting two more plunkings, Nimmo moved past not Hunt but Lucas Duda to claim the mark for most hit-by-pitches in a single Met season. He has fifteen marks overall on his body, not counting the couple he tried to sneak in when the umpires were being picky and ruled he made no attempt to elude what was coming at him. Some give some; Brandon gives all.

Hunt, the godfather of taking one for this team, did establish the franchise HBP record in 1963 with 13 and held it alone until 1997, when John Olerud unassumingly tied it. Duda’s impression of a tree trunk fooled pitchers into dinging him on the anatomy fourteen times three years ago. Nimmo has taken bruising to a whole new level. Congratulations?

We learned everything and everybody conspires against the Mets.

Not just those pesky Yankees batters who hit balls toward den Dekker. Not just those flinty Yankees pitchers who throw balls toward Nimmo. No, the whole universe. Why else would umpires eject two men wearing Mets uniforms who were, at most, only half-involved in the outcome of the game? First, home plate ump Larry Vanover tossed Pat Roessler, the hitting coach, for daring to point out what a crummy job Vanover was doing calling balls and strikes. Then, Hunter Wendlestedt thumbed Asdrubal Cabrera from the proceedings because Cabrera still gives a damn. Cabrera was called out on appeal of a checked swing and reacted in disgust, spiking his bat to the ground. Instead of Wendlestedt admiring that somebody assigned designated hitter participation for the day still has enough of a pulse to remain engaged in the outcome instead of strolling detached from defensive duties back to the dugout as presumably most DHs do in the overwrought softball league, the umpire who decided he himself is the attraction removed Asdrubal. Not pictured: Mickey Callaway racing to his player’s defense. Cabrera would be replaced with Devin Mesoraco. Not pictured: Devin Mesoraco doing much in the way of hitting, designated or otherwise.

Also conspiratorial, as long we’re into conspiracy theories, was Miguel Andujar being awarded second base despite fan interference on ball he hit to right. Some dope representing everything we identify with fealty to that facility’s host team reached several feet over the fence with a glove and treated his find as a home run caught. Proving we’ve come a long way since Jeffrey Maier was hailed by a besotted city for his precocious ingenuity, Andujar was penalized two bases and awarded only a double. He should have been ruled out. So should have a majority of the 47,102 in attendance just on principle.

We — or at least I — learned there is no hope for the hopelessly hopeful.

What a crummy game this matinee had become by the ninth inning, with the Mets trailing, 7-3, and Aroldis Chapman on the mound to nail down the non-save. Kevin Plawecki, who keeps his usefulness to himself, walked to lead off. Amed Rosario poked an infield single under Andujar’s glove (serves him right for conspiring with that doofus the right field stands). Still, what’s gonna come of it? Ty Kelly was sent up to pinch-hit for Matt den Dekker…is a sentence you wouldn’t expect to read from a description or account of a Major League Baseball game, but, you know, Kelly walked on four pitches to load the bases. Son of a gun, it brought Jose Reyes to the plate with at least a chance to do the very same thing. Four balls, none close to being ruled strikes by even this pack of crooked umps, resulted in a Mets run. Nimmo was next and Nimmo did a Nimmo, which is to say he set that hit-by-pitch record. It was now 7-5 and I wouldn’t get up from where I sat. Understand I wanted to get up for a diet cola refill a dozen or so pitches earlier, but I got it in my Mets fan head that something was happening, so I better not budge. The All-Star closer on the other side was wild as a March hare in July and if the Mets could figure out a way to stand by while he continued to self-immolate, well, call me Matt Franco in 1999!

Except it’s not 1999. It’s 2018. Chapman was pulled by his manager. Mesoraco’s manager, having little if anything to choose from on his bench, left Devin in to wreak havoc versus Chasen Shreve. Havoc wasn’t having it. Mesoraco slapped his way into a twin-killing One more run scored, but the bases all but emptied. There was a little fuss at the end, with Wilmer Flores up and Reyes on third, but the chemistry was not right. The game ended in an undesirable 7-6 decision. For all it mattered, I could have budged.

We learned the identities of two Oakland Athletic minor leaguers who are now two New York Mets minor leaguers.

Meet third baseman Will Toffey and relief pitcher Bobby Wahl. Meet them eventually, I suppose. Toffey is a Rumble Pony, Wahl a 51. Neither is a flaming hot prospect. Both are our concern because they — along with a satchel crammed with International Slot Money — were traded by the A’s to the Mets for more or less the best righthanded reliever we ever had, Jeurys Familia. Familia registered 123 saves as a Met. The only righty closer with more for us was Armando Benitez; I’ll take Familia. I would have continued to have taken Familia, especially had there been myriad saves to be had in our near future. Few are on the horizon, so business is business, and business dictated farewell to the arm that touched off more celebratory soirées than any in Mets history. Jeurys was on the mound when we clinched everything we clinched in 2015 and 2016, four preludes to champagne showers in all. The Mets have only poured bubbly over one another twenty times. Close your eyes and you’ll see Familia in the highlight reel of your mind.

Maybe those two minor leaguers will become major contributors. Maybe that International currency will be invested wisely. Yay, if any of it works out for us. I’m never thrilled to say goodbye to somebody who helped us prevail, especially when we’re doing so little of that of late.

These are the saddest of possible words:

Toffey and Wahl and slot

A pair of A’s and a bucket of bucks

Toffey and Wahl and slot

Exchanging our closer from all those wins

Not that Jeurys was devoid of sins

But Familia memories should elicit grins

Toffey and Wahl and slot

We learned Yoenis Cespedes has a couple of heels giving him hell.

We learned that late Friday night, actually. Callaway learned it later Saturday morning. Or so he said. Or he clarified that he knew what was up all along. I don’t know. Who listens to what Mickey Callaway says in hopes of learning anything anymore? While the Cespedes mess indeed represents a blob of bad form on the part of this disorganized organization, I think it’s worth remembering a player who lifted us to unimagined heights in 2015, in conjunction with Familia and a cast of characters that is no longer extant, is hurting. Imagine this franchise, under this ownership, going to the World Series. It’s beyond the imagination in 2018. It wasn’t on the radar as late as 2014. It was barely wishable as late as this date in 2015. But along came Ces on July 31, and up the ladder we went.

In light of Yoenis’s contributions to the Mets briefly standing for something better than they did before and do now, I lean toward thinking he’s not solely at fault in whatever communication mishap has bogged down his return to action. In West Wing terms, Yo’s actions align with President Bartlet keeping his MS quiet. The lot of us has responded as Toby Ziegler did: in stunned disbelief that nobody thought to mention it until now. None of us has been Donna Moss asking if the president is in pain. Maybe that strain of thought, whatever the heft of President Cespedes’s contractual status and the irritation inherent in his characteristic diffidence, should cross our minds a little. In non-TV terms, I hope he feels better soon.

Ces did return on Friday. Homered and everything. Then he revealed his heel problems and reported that if he opts for the surgery he indicated he ultimately needs, he’ll be out quite a while, deep into 2019. By no means is that what anybody wanted to hear, nor was it the avenue by which we would figure something like it would be said. We were reminded Saturday what a Met lineup without Yo looks like. Callaway used two DHs and got nothing for his trouble but one ejection and a devastating double play. When we get back to baseball played like it oughta be, Cespedes will have to stand on two aching heels and man left field or first base. Also unimaginable. We’ll see what an MRI and a visit to a specialist yields. Maybe the Mets will put out a press release when they know something. They don’t at this time retain a general manager who speaks on issues fans would want to know about.

They still have fans, somehow.

by Jason Fry on 21 July 2018 12:13 am Break up the Mets! They’re 2-2 against the Yankees!

Actually that already appears to be happening: the Mets left Robert Gsellman in to throw a ton of pitches against the Yankees Friday night while Jeurys Familia sat in the bullpen in a sweatshirt, got hugs from teammates and was spoken of evasively in postgame interviews. He’s either been traded or is about to be traded, and we all know he won’t be the last ’18 Met to get a new address.

If Friday was Familia’s last game as a Met, at least he saw an exciting one. Exciting and nauseating — it was more bar brawl than athletic contest. Noah Syndergaard, Seth Lugo and Gsellman all labored mightily to hold the Yankees at bay, with none of them recording a 1-2-3 inning. (Plus Syndergaard departed after a drop in velocity, a mound visit and extensive conversations with Dave Eiland and the trainer. Mickey Callaway says he’s fine, but this is the Mets we’re talking about.)

The three pitchers got — stop me if you’ve heard this one before — no help from their defense, with Amed Rosario a particular culprit. Rosario had one of those games that make you grit your teeth and mutter platitudes about growing pains, ending his night with a throw to first that came after the game was over. Better to get an out you don’t need than to need an out you don’t get, I suppose, but yeesh nonetheless.

Fortunately the Mets outhit the ill-advised things done or not done with gloves. Asdrubal Cabrera (speaking of Mets likely on the move) and Michael Conforto led the charge, with Yoenis Cespedes returning and sneaking a home run off the foul pole. The Mets built a 6-1 lead, but the Yankees kept coming, leaping out of closets and dropping out of attics like a particularly stubborn slasher-movie villain. Devin Mesoraco‘s quick footwork kept the game from being tied 6-6 in the 8th, and Cabrera’s leadoff single in the 9th led to a much-needed insurance run and eventually an enormous sigh of relief. It felt like the Mets were going to lose this one, but somehow they didn’t. We’ll take it.

Still, every good slasher movie has a sequel or 12, and these two teams will be back at it for a Saturday matinee. I’d advise everyone wearing blue and orange to lock their windows and doors and sleep with a gun under their pillow.

Oh, and playing better defense might help too.

* * *

Even disappointing seasons go on — oh boy, do they go on. As Mets fan, we’ve got plenty of experience with watching a team play out the string — and at least for me, this is about the time nostalgia makes an appearance on the calendar. It’s a survival instinct, I suspect: if the current Mets aren’t going to offer much to get excited about, I look for solace in remembering previous iterations of the team.

I regard nostalgia a bit warily — the novelist Don DeLillo once called it “a product of dissatisfaction and rage” and “a settling of grievances between the present and the past.” But one nice thing about it is that it blurs losses and disappointments.

I’ve rattled on a few times about making custom cards for those Mets who never got Met cards, or cards of any sort. I’ve made more than 100 by now, filling out The Holy Books with cardboard memorials to September callups, May unconditional releases, momentary acquisitions and lost-cause roster fillers. Which means I avidly watch Topps’s auctions of old slides from previous decades — sometimes to buy, other times just to admire. Those Topps shots offer rare glimpses of momentary Mets (including some who only suited up in spring training), and many of them are wonderful baseball photos even if you don’t care about bubble-gum cards.

By now I can spot a classic-era Topps shot at a glance — there’s a quality to the lighting and the poses that’s unmistakable, down to the photographers’ habit of composing portraits so the player is level instead of the horizon. (This is known among baseball-photo dorks as the “Topps lean.”)

Joe Nolan collected 11 plate appearances in September 1972, when a rash of injuries left the Mets in need of catching help. (Nolan’s first hit would have to wait until he reappeared with the Braves three years later.) For a momentary Met, Nolan’s been amply photographed, so I wasn’t too excited when Topps unveiled two new Nolans last week. Joe Nolan collected 11 plate appearances in September 1972, when a rash of injuries left the Mets in need of catching help. (Nolan’s first hit would have to wait until he reappeared with the Braves three years later.) For a momentary Met, Nolan’s been amply photographed, so I wasn’t too excited when Topps unveiled two new Nolans last week.

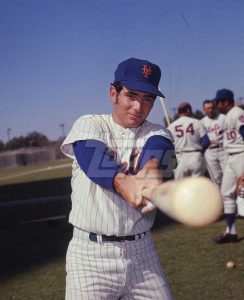

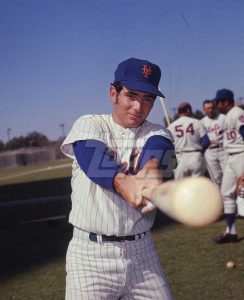

But one of those shots caught my eye not because of Nolan, but because of who else was in it. No. 54 is longtime Mets coach Rube Walker, No. 14 is of course Gil Hodges, and No. 20 is Tommie Agee. That’s three Miracle Mets, legends all, captured as bystanders as a kid who’d never appeared in a big-league game pantomimed a big-league swing.

Nolan’s minor-league record and the look of the photo (trust me on the latter) fix the date of the photo: it’s spring training 1972, meaning it was snapped in the final weeks of Hodges’s tragically short life. I still can’t believe I’m older than Gil Hodges ever got to be — he died two days shy of his 48th birthday. In some better universe Hodges lived and is now a stooped but still sharp man of 94. Perhaps he handed the managerial reins over to protege Davey Johnson, and is greeted rapturously by Citi Field crowds when he throws a first pitch before heading upstairs to spend an inning talking baseball with Gary, Keith and Ron — who inevitably marvel that his big hands are still strong.

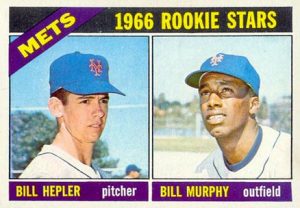

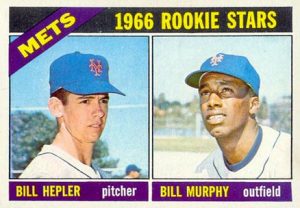

Billy Murphy is the opposite of Joe Nolan — present on a roster for an entire season  but rarely photographed. Murphy was a Rule 5 pick who spent all of 1966 with the club, as per rules at the time; he got a high-number card in the ’66 Topps set, which he shares with another Bill, the somewhat better-known Bill Hepler. It’s one of the more expensive cards in that set, featuring Murphy squinting up at something — whether it was a pop-up, zeppelin or interesting Florida bird is something we’ll likely never know. but rarely photographed. Murphy was a Rule 5 pick who spent all of 1966 with the club, as per rules at the time; he got a high-number card in the ’66 Topps set, which he shares with another Bill, the somewhat better-known Bill Hepler. It’s one of the more expensive cards in that set, featuring Murphy squinting up at something — whether it was a pop-up, zeppelin or interesting Florida bird is something we’ll likely never know.

When I made a custom card for Murphy, that small photo was all I had. So I grafted Murphy’s head and shoulders onto the body of Cleon Jones, as captured on his iconic ’69 card. Which was itself quite possibly shot in 1966 — when the players’ union started flexing its muscle in the late 1960s, one of its first showdowns came with Topps. Numerous players refused to pose for Topps photographers unless they were paid more than the standard agreement, leaving the card company stuck using older images.

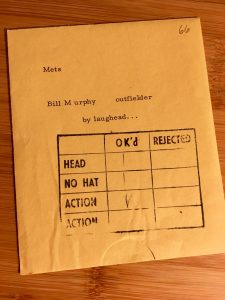

A couple of weeks back, Topps put up a pair of Murphy images for auction — a hatless shot (taken for insurance in case of a trade) and a pretty good portrait with cap.

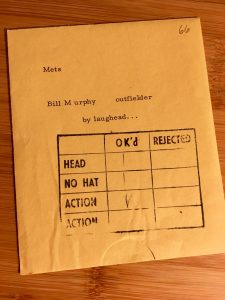

I won the latter, and it came with a fun bonus: the half-envelope Topps had used in its filing system. It tells us that Topps had (in this folder at least) three Murphy shots: one each of Head, No Hat and Action. I wonder if the action shot was the one used for his 1966 card — if so, the slide would have been physically cut down to fit the space. That half-envelope also gives us the name of the photographer: Jim Laughead, a legend who essentially invented the basics of sports photography. (Laughead called his standard football poses “the huck ‘n’ buck.”) I won the latter, and it came with a fun bonus: the half-envelope Topps had used in its filing system. It tells us that Topps had (in this folder at least) three Murphy shots: one each of Head, No Hat and Action. I wonder if the action shot was the one used for his 1966 card — if so, the slide would have been physically cut down to fit the space. That half-envelope also gives us the name of the photographer: Jim Laughead, a legend who essentially invented the basics of sports photography. (Laughead called his standard football poses “the huck ‘n’ buck.”)

But you’re probably wondering: who’s Billy Murphy? Nicknamed “Murph the Surf,” he was born in Pineville, La., but grew up in Tacoma, Wash., where he was a three-sport star at Clover Park High and caught the eye of Yankees scout Eddie Taylor. Murphy struggled in 1963, his second year in the Yankees’ system, missing a month with blood poisoning, of all things: he cut himself sliding and, with no trainer available, treated the injury himself. 1964 was a washout, but Murphy rebounded to hit .291 with power and speed for Binghamton in 1965, a performance that caught the Mets’ eye.

Murphy didn’t play a full game with the Mets until a month of the season was in the books; he collected his first three hits on May 13, when he came in for Jim Hickman against the Giants. His first hit was a three-run homer off Ray Sadecki in the fourth; he then singled in the 12th off Frank Linzy and in the 16th off Bob Priddy. (The Mets lost an inning later on a Jim Davenport homer off Murphy’s fellow Lost Met Dave Eilers.)

Murphy’s other ’66 highlight came in Philadelphia on Aug. 20: with the Mets and Phillies tied 4-4 in the 11th, Murphy ran headlong to center field with his back to home plate, snagging a long drive by Richie Allen as he smashed into the fence 430 feet away. The ’66 Mets being the ’66 Mets, Murphy’s great play only delayed the inevitable: Bill White immediately doubled off Dick Selma, Tony Gonzalez singled him in, and that was that.

Murphy never made it back to the big leagues, bouncing around with in the Mets, Cardinals and Cubs farm systems before retiring after the 1970 campaign. But he’s a Met, a proud member of The Holy Books, and it makes me happy to recall him while holding a little bit of baseball-card history.

Weirdly, that’s not the only reason the 1966 Mets have been on my mind. I was looking for footage of Pete Harnisch getting into a fight in May 1996, which led to John Franco being ejected on John Franco Day, a spectacle Emily and I watched from the Shea stands on a sparkling spring day. (Doug Henry blew the game in the ninth; Rico Brogna won it with his second homer of the day in the 10th. It’s amusing to try and find the fight in this Baseball Reference game log.)

I didn’t find a clip of the fight, but I was offered something else: a broadcast of the Sept. 17, 1966 game between the Mets and Giants at Candlestick, with Juan Marichal facing Dennis Ribant. I started listening out of curiosity, but what I really liked was I had no idea who’d won. (And I’m not going to tell you: Google the date at your own risk.) Ralph Kiner is on the mic, his voice welcome and familiar, there are lots of commercials for Rheingold, Giants fans blow vuvuzelas throughout the game, and you get little gems such as Ralph marveling at the speed of young Bud Harrelson and looking forward to a start in Houston by 19-year-old Nolan Ryan, who at that point had all of two innings of big-league ball under his belt. (The Astros would knock Ryan out with four runs in the first.)

And the broadcast began with something I certainly didn’t expect: a Mets jingle I’d never heard before. Here are the lyrics, which I swear I am not making up:

In all Baseball Land

There are no fans so grand

As our Mets fans

When we play other teams

Oh what blood-curdling screams

That’s our Mets fans

But when Mets fans shout “Go!”

What they mean we all know

We’ve got no place to go … but up!

I’ve been at this a while. I’ve heard of Homer the Beagle, lived through Mettle the Mule, heard “Meet the Mets” bastardized as cheesy soft rock and then restored, and endured “Our Team, Our Time.” But that one was new to me. Listen for yourself.

|

|