The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 January 2017 7:12 pm The sample size is only four Saturdays, but I can definitively report that it’s always colder the morning of the Queens Baseball Convention than it was at any point in the preceding week. Sometimes it snows. Sometimes it snows a lot. It snowed so much in 2016 that there was no QBC.

That’ll happen in January. Ideally, you’d hold a baseball convention in Queens when the weather is more amenable to baseball in Queens, but then you’d have baseball in Queens, and you wouldn’t need the convention. Depending on how you set your ballological clock, we have baseball for six to eight months out of every year. We’re varying degrees of fine from Pitchers & Catchers until the final out of the World Series. We’re great between Game One and Game One Sixty-Two. It’s January’s white space that envelops us in endless gloom, whether a blizzard is doing its worst or flurries are making a nuisance of themselves.

This most recent Saturday, the date of the most recent QBC, was indeed chillier than the most recent Friday and Thursday and so on. It’s a fair trade, I suppose. It’s never warmer in January than it is once you get inside and rub your hands in front a roaring Hot Stove, surrounded by those with whom you relish sharing the fire.

You know how nice it is to come in from the cold? That’s QBC if you’re a Mets fan. QBC is home. You’re where you’re belong when you’re there.

QBC, inaugurated in January 2014, was such a good idea. Still is. We had nothing like this as Mets fans. We should have always had something like this. Other team’s fans have it, arranged by the teams themselves. The Mets don’t do that kind of fan outreach. Perhaps it’s enough that they’ve lately begun to give us seasons worth looking forward to. Let the Mets get spring, summer and autumn right. We’ll handle winter as best we can.

That’s where QBC comes in, a Mets fanfest by and for Mets fans, all of whom take the responsibility seriously. Not just the principal organizers and raft of volunteers (though they work especially hard to make it happen) but everybody who shows up. QBC clicks because we the Mets fans breathe it into existence with our passionate determination. Or maybe our determined passion. Either way, give Mets fans a time and a place to be Mets fans, even without a Mets game, and we will come through.

The 2017 rendition moved from its ancestral home at McFadden’s Citi Field to Katch Astoria, multiple 7 stops and an N trip west of Flushing. On balance, it was an ideal locale. It was in Queens, it opened itself up to baseball and we convened. Plus the staff was friendly and the food was tasty. Can’t ask for much more when you’re already blessed with so much.

Like being in the company of your fellow Mets fans. Like seeing old friends and making new acquaintances over Mets talk. Like getting a load of this jersey and that t-shirt. Like being in a room where somebody’s telling you what the Mets’ record was in 2016 when Yoenis Cespedes wore a compression sleeve on one arm versus their record when he wore it on the other arm and realizing you’re in the lone spot on earth where that’s treated as valuable information. Mets fans should never have to apologize for being Mets fans. I didn’t hear a “sorry I am what I am” all day.

Being a Mets fan means never having to say you’re sorry. Our Love Story won’t allow it.

My QBC day, besides sitting and listening and laughing and loving, was devoted to two assignments. First, I presented an award named for one Met legend to another Met legend on behalf of the ultimate Met legend. I don’t throw around the phrase legend lightly. Each legend in question is connected to the 1969 Mets, engineers of the most legendary championship in world history (we’d also accept 1986 as a correct answer). The prize was the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award, a token of our esteem we came up with before the first QBC to continue to keep the name Gil Hodges aloft in the minds of Mets fans. The recipient this year was Tom Seaver, chosen because a) we are on the cusp of the 50th anniversary of Tom’s major league and Met debut and b) do we really need a reason to give an award to Tom Seaver? He had three Cy Youngs, a Hickock Belt and a plaque in Cooperstown. Tom has been attracting honors for a half-century.

QBC drew hundreds of Mets fans, not to mention special guests Tim Teufel and Bobby Valentine, but a Napa Valley vintner can’t necessarily pop on over to Astoria for every bauble bestowed in his direction. We understood that. We decided to honor him anyway. He’s Tom Seaver. We figured “the academy” would accept on behalf of our winner and we’d continue to talk about him in absentia. Later we could box up the award and ship it to California.

A funny thing happened on the way to the podium. One of the organizers came up to me as Teufel (who hit an extra-inning grand slam with his insights and anecdotes) was wrapping up. Hey, he whispered, Art Shamsky just showed up. He wants to talk to Mets fans. Would you mind moderating?

As requests that come out of right field go, this was a can of corn. Why, yes, I’ll be happy to host Art Shamsky, 1969 Met, for a spell. Then another organizer sought me out. Art’s gonna accept the award for Tom. Can you present it to him?

Yeah, I’m really put upon at these things.

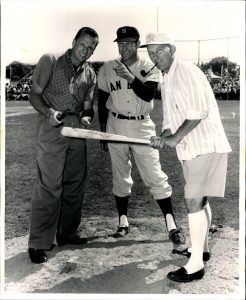

A typical Saturday afternoon in January? Not when you find yourself elbow-to-elbow with Art Shamsky. (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Graziano) For about twenty minutes, it was an afternoon at the Improv at Katch Astoria, but I haven’t been a Mets fan for forty-eight years without being able to vamp a little when positioned elbow-to-elbow with a Mets legend. I once ate pizza in the company of Cleon Jones. After I didn’t faint from delight at that encounter, I realized I possessed the emotional reserves to handle proximity to any 1969 Met.

Art was great at QBC, which goes without saying. Art was a great Met from 1968 through 1971, peaking in unison with a couple dozen other fellows in 1969. He likes to say he played thirteen years of professional baseball, yet nobody asks about the other twelve. I thanked him for 1970 and 1971 because I watched him then and he was one of my childhood favorites. (I omitted his first Met year because I wasn’t yet on board in 1968; my bad for being five.)

Mr. Shamsky did us the solid of accepting for Mr. Seaver and then set up shop at a table to greet his public and offer up his evergreen book about the only season anybody ever asks him about. I went back to being in the audience for the other presentations, particularly enjoying the bejeesus out of Bobby V taking what we shall call an unorthodox route to storytelling. He tended to mush together different seasons at times, but he always tracked down the payoff at the wall. Bobby seems as fond of his Mets as we are. (He’s also fond of Japan, but doesn’t sound like he’ll be rushing off there anytime soon despite previous reports.)

At five o’clock or so, the last hour of QBC, I was back on stage for our 50th anniversary Seaver retrospective, my second assigned task. We didn’t have Tom, but we had three writerly perspectives to provide: one from me as moderator not to mention lifelong Terrifophile; one from Bill Ryczek, who wrote and talked about Tom’s rookie year; and one from Matt Silverman, who spoke from one of his many volumes regarding the night the music died forty years ago this June 15. An hour spent delving into what made Seaver Seaver is as good an hour as you’ll have all winter.

When the day was done, January was closer than ever to ending. We who indulged in QBC helped each other clear away excess winter, so you’d have to call it a very productive Saturday. I’d even go so far as to judge the streets of Astoria slightly warmer on Saturday night than they had been Saturday morning. Baseball works wonders sometimes.

You can listen to the presentation I did with Art here and the entire panel discussion among Bill, Matt and myself here. Below is what I wrote in advance for the occasion. It’s not exactly what was delivered verbatim due to the revised-yearbook nature of the proceedings, but the text should give you a sense of why we wanted to talk about Tom Seaver…besides the fact that he’s Tom Seaver.

***

When we came up with the concept for the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award in 2013, we had two goals in mind.

One was to cast a glow around the memory of the manager who led the Mets to the promised land when nobody else dreamed such a journey was possible. Gil died two days shy of his 48th birthday after four seasons at the helm in Flushing. It was too soon then, it’s too soon now. What Gil did and who Gil was should never be forgotten, and this award is our small way, as Mets fans, of trying to keep his legacy alive.

Our second goal was to annually thank a special figure from Mets history for warming our hearts, brightening our spirits and lighting our way. We meet in winter. Of course we want to spend a few minutes thinking of somebody like that. What is baseball for but to get us through the times when there is no baseball?

In the first three years of QBC, we were honored to present the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award to Gil Hodges, Jr., who accepted on behalf of his late father; to the Glider, Ed Charles; and to Buddy Harrelson. We were canceled by a blizzard last January, but one of QBC’s organizers, Dan Twohig, made the pilgrimage out to Central Islip and gave the award to Buddy between games of a Long Island Ducks doubleheader, and Buddy, like Gil Jr. and Ed, was extremely gracious and talked about how much Gil meant to him.

This year, we don’t have our recipient with us, but he takes a backseat to nobody when it comes to warming hearts, brightening spirits and lighting the way for Mets fans. The 2017 winner of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award is Tom Seaver.

We’re going to get into Tom’s career later, as we celebrate a truly Amazin’ milestone in his and the Mets’ story, but when you think about Tom Seaver, whether as…

• the rookie phenom immediately establishing himself as one of the best in the business;

• the incandescent star pitching his team toward a most improbable championship;

• the indefatigable ace continually defining and perfecting his craft across a generation;

• the prodigal veteran son bringing everybody out of their seats and everybody’s heart out of their chests upon his overdue return to where it all started;

• the beloved legend trotting to the mound one more time to take another bow as his number, like him, eased into retirement;

• or the all-time great carrying OUR banner for the first time into the Baseball Hall of Fame

…well, I don’t know how you’re not warmed, you’re not brightened and you’re not absolutely lit at the thought of one George Thomas Seaver, a.k.a. Tom Terrific, which he always was and always will be.

Tom, as you probably know, is a vintner in California these days, hard at work making the best of wine, just as he made the best of every pitch. A continent away, we wish to invoke a few of the sentiments he’s shared about the manager and the man he revered, Gil Hodges.

This from an interview published in 1974, reflecting on Gil’s influence and his passing:

“He was an outstanding man. He was a man’s man and demanded total respect. I learned many things about the game from him. Probably the most important was what it meant to be a professional, and how important self-control was for you to perform as a professional. It was almost like losing a second father. I loved the man and I tremendously admired him. I had a tremendous amount of respect for him.”

This from his Hall of Fame acceptance speech in 1992:

“The one guy who taught me how to be a professional, to really be a pro, [was] Gil Hodges. If [there were] other people [who] taught me how to get here and what to do when I got here, Gil Hodges told me how to be a pro and stay here — the most important man in my life from the professional standpoint of my career. And God, I know that you’re letting Gil look down here today and I know that he is part of this.”

And this from just last year when a reporter asked him if he was bothered — like so many of us are — that there’s no Tom Seaver statue outside of Citi Field:

“I’m not dead yet. So I’d rather it be Gil Hodges. He’s the most important person in the franchise.”

And that’s coming from THE Franchise. So it seems more than appropriate…it seems Terrific that we can take it upon ourselves to, one more time, link manager and pitcher where they belong, at the peak of our appreciation.

So ladies and gentlemen and Mets fans of all ages, let’s transport ourselves to Shea Stadium, to 1969, to pregame introductions during the World Series. Let’s give it up for No. 14, the manager of the New York Mets, and No. 41, starting pitcher for the New York Mets. Let us, from the upper deck of our souls, say “thank you” to Gil Hodges and to Tom Seaver.

***

I mentioned a milestone. It’s one of those anniversaries I’m still getting used to since 2012, when the Mets — and I — turned 50. As someone who’s approximately the same age as the Mets, I find it hard to believe we both have things that happened to us 50 or more years ago, but time will do that to a person and a team.

On April 13, 1967, the best of things happened to the Mets. Wes Westrum, the manager between Casey Stengel and Gil Hodges (give or take a Salty Parker), handed the ball to a rookie right-hander, to start the second game of the season, at Shea. It was the rookie’s major league debut. The team and the sport would never be the same.

Tom Seaver faced the Pittsburgh Pirates that Thursday afternoon. The Mets won. A precedent was established. Seaver and winning went together like no Met and no such result ever had before. Tom was about to become one of the best pitchers baseball has ever known and, hands down, the greatest Met we have ever known. There was nobody remotely like him prior to April 13, 1967, and there’s been nobody quite like him since.

It’s been fifty years and he’s rarely been matched by any pitcher from any team and he hasn’t been touched by any Met at any position. I think it’s fair to say he’s had quite the half-century.

Tom’s primacy as the Met of Mets is so established and so obvious, that after 50 years, we might not fully comprehend the texture of what he achieved on the mound for us from 1967 forward or his apparently immovable place atop Met history. Our mission today, then, is to explore the accomplishments and legacy of Tom Seaver as we celebrate 50 years of Tom being our indisputable best player.

We could frame Tom Seaver’s grandeur by quoting statistics, and I’ll be happy to note a few a little later, but to get us started on our commemoration of 50 Years of No. 41, I want to take us to any given year in the early to mid 1970s and either remind you if you were around or let you know if you weren’t what life was like for a Mets fan coming of age in the Age of Seaver.

In January, you leaf through the sports section and your face lights up because there’s a picture of Tom Seaver, maybe posing in the snow at Shea Stadium, maybe indoors, and he’s signing his contract for the upcoming season. Spring Training can’t be far off.

In February and March, you go to your local candy store or newsstand and you start to look for preseason magazines, and somewhere on their covers, you find Tom Seaver. You grab those and, either at that place or maybe at a bookstore, you find the paperback guides to the season ahead. If Seaver’s picture isn’t on those covers, his name figures prominently in the text as soon as you turn to the Mets preview. You grab those, too.

By March, baseball cards are out, and of course you’re buying as many packs as you can reasonably handle. You rip them open in hopes you’ll find a Tom Seaver. If you’re fortunate, your year of collecting is made. If you’re not, there’s a very good chance you’ll find some kind of insert with Tom’s picture, or a leader card with Tom’s face, because he’s always leading the league in something. You might get Tom Seaver In Action, or Tom Seaver’s Boyhood Photo or something referring to how Tom Seaver helped the Mets to the playoffs and World Series the year before. Those are pretty good cards, too.

Come April, Opening Day is upon us. You don’t need to check to see the probable pitchers because you know who’s starting the season for the Mets. Tom Seaver has been the Opening Day starter every year since he established himself and no Met manager is going to mess with that tradition. It works. The Mets almost always win on Opening Day.

As the season gets going, you take special pride in scouring the statistics in the Sunday papers. You don’t have to scour far, because Seaver, NY is inevitably at the top, whether you’re looking at wins or innings pitched or winning percentage or earned run average or strikeouts. If you’re going to a game, you hope he’s pitching. Even if he’s not, you can’t miss him. He’s on the cover of the yearbook. He’s on the cover of the scorecard. He’s Tom Seaver. He’s everywhere.

July comes along and it’s All-Star selection time and your question about who will be representing the Mets goes simply, “Tom Seaver and who else?” Tom is the personification of an All-Star, whether he’s starting the game, coming on in relief or just tipping his cap among his peers. Coincidentally or not, the National League is always winning these games.

The season wears on. Seaver keeps pitching. Usually, he wins. Sometimes he pitches more than well enough to win but the Mets don’t score for him. But every start you can anticipate greatness. Maybe he’ll throw a complete game. Maybe he’ll throw a shutout. Dare we dream of a no-hitter? Probably he’ll be on Kiner’s Korner, where he and Ralph have a second-nature rapport, legend to budding legend. You’ll hear Tom talk seriously about his pitching and you’ll hear Tom cackle giddily about his hitting.

By September, if the Mets are in the race, you’ll look forward to those nights or afternoons when Tom starts. You’ll figure you’ll pick up ground on the Pirates or put more distance in front of the Cubs. If the Mets aren’t in the race, there’s still plenty to get excited about. Tom is nearing 20 wins or Tom is extending another strikeout record or Tom is lowering his ERA out of reach of any other pitcher. Whether at the beginning or end of the season, Tom Seaver always keeps you in the game.

If Tom is still pitching beyond earliest October, you know it’s been a great year to be a Mets fan, and you can keep watching him on TV doing what he does best. If Tom is done, you look forward to November and reading about the Cy Young voting. Tom probably deserves to win another award. If he wins it, you’ll be happy. If he doesn’t, you’ll be sure he should have. If nothing else, you’ll have another reason to have Tom Seaver on your mind, which is the next best thing to having Tom Seaver on the mound, which will happen again soon, because by January, there’ll be a picture of Tom at Shea, signing another contract, ready to begin another year. Once more, Spring Training can’t be far off.

This is what it was like to grow up and mark time with Tom Seaver. It was hard to fathom it hadn’t always been this way and that it wouldn’t always be this way.

***

The beauty of Tom Seaver was twofold. There was watching him, his aesthetically perfect drop and drive motion, the power-pitcher who led with his legs, got his right knee dirty and blended rising fastballs, curves and sliders consistently for strikes. That was what you could see. You could only imagine or wait for his postgame remarks to get a handle on what he was thinking. As ideal as he was physically, he was just as beautiful when it came to the mental game.

Then there were the numbers No. 41 put up. The basics of his career are easy enough to quote: 311 wins, 3,640 strikeouts, an ERA of 2.86 over 20 seasons, 3 Cy Youngs, 12 All-Star selections, 16 Opening Day starts, 5 one-hitters, 1 no-hitter — albeit in the wrong uniform — and a 10-inning complete game World Series victory that put the Mets on the brink of a world championship.

Though they didn’t show up in the box score, there also seemed to be a new book about or “by” Tom Seaver every year, including one I remember using for a book report in sixth grade. I made the last paragraph nothing but his year-by-year statistics to date, and even at the age of 12, I knew that was a bit much, so I don’t want to drown us in numbers. Still, those numbers never fail to floor.

Here, as promised, are a few numerical notes to consider when considering Tom Seaver.

• In the first ten years of his career, 1967 through 1976, when he was becoming and had become “Tom Seaver” for us, Tom compiled 182 wins, 2,334 strikeouts and a 2.47 earned run average. You know who else in the major leagues could match that profile? Nobody. Nobody else did that during the first ten years of Tom Seaver’s career. It wasn’t just bias that convinced us he was the best pitcher in baseball. He was.

• Those were the traditional markers of what made a pitcher outstanding when Tom was coming up. WAR, or Wins Above Replacement, did not enter our lexicon for several decades. When it did, we found, according to Baseball Reference, that Tom Seaver was worth 71.2 Wins Above Replacement for the ten years starting in 1967 and ending in 1976. You know what pitcher did better in baseball? None. Nobody else has a better WAR for that decade. Gaylord Perry finished about 5 wins above replacement behind, and Fergie Jenkins more than 10. They’re the runners-up.

• Go on Baseball-Reference, go to the page with National League pitching leaders for 1973 — a good Met year, to be sure — and check out who led the league in SEVENTEEN different statistical categories, traditional and advanced. Wins weren’t even among them, a symptom of the Mets not being the most offensively robust of clubs throughout Seaver’s stay. For the record, Tom had “only” 19 and won the Cy Young anyway.

• The one truly troubling season in Seaver’s first decade was 1974, when he was bothered by a sciatica condition and finished a horrifying — for him — 11-11, his ERA skyrocketing to 3.20. And yet, when you click the Baseball Reference page forward from 1973 to 1974, you still see Seaver’s name dotting the leaderboards, in the Top 10 across all kinds of interior categories and placing fourth in Pitcher WAR. We didn’t know it at the time, but even when Seaver was at his worst, he was among the best. As an aside, when Seaver was nearly at his best, we weren’t easily satisfied. I clearly remember a comment from Bill Mazer, the longtime sportscaster in New York, then, in 1972, the host of the Met postgame show on WHN, saying very definitively, sure, Tom Seaver has won 20 games, but “it hasn’t really been a Tom Seaver year.” That’s how high a standard he set for himself and for all of us.

• One more quick statistical glance, from 1983, at which point Tom, a Met for the first time since, if you’ll excuse the expression, June 15, 1977, was 38 and pitching for a last-place team. The won-lost record wasn’t much — 9-14 — and the ERA, 3.55, indicated he was clearly on the back end of a fabulous career. Even with age and wear and a not very good Mets squad behind him, Tom comes in tenth in the NL in innings pitched, ninth in games started and seventh in fewest hits allowed per nine innings. If he’s not one of the best pitchers in the league by his seventeenth season he’s definitely one of the better ones. And, as we’d find out over the next three years, he still had plenty left in the tank.

But the tank would be found elsewhere in 1984, just as it was transferred to points west in 1977. “Tanks for nothing” we’d find ourselves saying twice to two sets of Mets management.

***

Tom Seaver pitched his last official inning in 1986, curtailed a comeback in 1987, had his number retired in 1988 and entered the Hall of Fame in 1992. He hasn’t added to his Met totals since any of those milestones, yet he maintains his place as the Greatest Met Ever, unchallenged 50 years after he basically invented the concept of Great Mets.

Have you ever seen a Greatest Met list that wasn’t topped by Tom Seaver? Have you ever tried to make one? It’s not so much that it would be sacrilege — it would be inaccurate.

Dwight Gooden’s 1985 might have surpassed any of Seaver’s individual seasons as the crown jewel of pitching years, but Doc couldn’t keep up that kind of accelerated pace for long.

Mike Piazza, the second player to go into the Hall as a Met, gave us indelible memories, connected on critical swings and was primarily responsible for perhaps the most dramatic era of Mets baseball — there’s a book coming out about it, I hear — but he established the first half of his legend elsewhere.

David Wright is all Met all the time and he already owns almost every Met offensive record there is, but the Captain, ever the good soldier, would be the first to tell you that as Terrific as we think he is, his cumulative impact on the franchise hasn’t come close to that of The Franchise.

Darryl Strawberry hit more home runs than any Met. Dave Kingman hit them longer than any Met. Yoenis Cespedes is as breathtaking as any Met. Buddy Harrelson was about as reliable as they came. Nobody was more dynamic on the basepaths than young Jose Reyes, unless it was Mookie Wilson. If anybody swung sweeter than Rusty Staub, it was John Olerud. Gary Carter pushed the Mets close to a championship after Keith Hernandez steered the ship around. Carlos Beltran did almost everything right. So did Edgardo Alfonzo. Rey Ordoñez did one thing well, but might have done it better than anybody, Met or otherwise. Ed Kranepool, for eighteen seasons, is a chapter unto himself. Jerry Koosman still hasn’t lost a postseason start for the Mets, and he made a bunch. You Gotta Believe in Tug McGraw, in Jesse Orosco, in John Franco, even, when it comes to closing games. We cross our fingers that someday we’ll be at a discussion like this and praising to the high heavens the likes of Syndergaard and Harvey and Matz and deGrom and all they did and how long they did it for.

We have no shortage of great Mets. But we have only one Tom Seaver, the greatest of Mets. He started being great fifty years ago this April. He has yet to stop.

by Greg Prince on 25 January 2017 5:03 pm Come to Astoria this Saturday for a Terrific time. The Queens Baseball Convention will be there, at Katch Astoria, 31-19 Newtown Avenue, and I’ll be there, talking up Tom Seaver at 5 PM. I’m moderating a panel commemorating and celebrating the 50th anniversary of Tom’s major league debut and his legacy as the greatest Met ever, culminating in the presentation of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award (albeit in absentia) to Tom. Joining me on the panel will be two authors who know their Seaver: Bill Ryczek, who wrote the essential The Amazin’ Mets, 1962-1969, and Matthew Silverman, who’s written just about everything else. We should each have some of our work on hand if you’re interested.

Doors open at 11:30 AM. Other panels include Q&A with Bobby Valentine and Tim Teufel and an array of deep Met dives. Best of all, you’ll be surrounded by Mets fans and Mets baseball in January. For more information, take a look here. For a great day, see you there.

And listen in here, to the Rising Apple Report, for a mountain of Seaver talk and general Metsian joviality.

by Greg Prince on 25 January 2017 4:49 pm

by Greg Prince on 19 January 2017 3:36 pm Tim Raines can stop retroactively beating the Mets now. Ever since his Hall of Fame election came into view a couple of months ago, I’ve seen two clips repeatedly: Tim Raines beating the Mets with his baserunning (sliding into second base on a successful stolen base attempt) and Tim Raines beating the Mets with his bat (hitting a grand slam off Jesse Orosco when neither a World Series-saving lefty nor the scourge of collusion could stop him). Based on archival footage, a Montreal Expo continuously ran wild and slugged mightily against the New York Mets, thus making the rooting life of a Mets fan endlessly miserable.

Did anybody tape Raines doing anything else besides beating the Mets?

Whoever picks the clips to illustrate the essence of a Hall of Fame candidate pretty much got it right, because those actualities are actually how I remember Raines, a fearsome opponent on a regular basis throughout the 1980s, when if you were asked when you thought Rock might roll into Cooperstown, you’d say he’s on his way there now and he’ll no doubt make it before long.

He was on his way, but he ended up there after long…way after. Raines, who debuted with Montreal in September 1979 and partook of a few more sips of coffee the next year, was around forever before anybody had heard of his fellow Class of 2017 inductees Jeff Bagwell and Ivan Rodriguez. I was watching this guy beat the Mets when I was in high school, and I assure you I haven’t been in high school for quite a while. The writers, not some veterans committee, just voted him in. Such a development implies recency. It’s as if I wasn’t in twelfth grade two-thirds of my lifetime ago. Thanks for the shot of youth, BBWAA. See what you can do about giving the Grammy for Record of the Year to “Bette Davis Eyes” next month.

I graduated the same spring Tim Raines truly burst onto the scene, 1981 — and if any ballplayer could be said to have burst onto a scene, it was Raines. I was hoping it would be another leadoff hitter.

Nineteen Eighty-One was the second year in which the Mets were scheduled to rise from the valley of the ashes the late ’70s left behind in Flushing. The Magic was evanescently Back in 1980. It was advertised as Real going forward. One of the wizards who was going to abra-ca-dabra us out of the second division was a speedy rookie outfielder named Mookie Wilson. The prospect reports predicted Mookie, who we glimpsed late the previous season, was gonna get on base and run like no Met before him.

And he did. Just not immediately. Mookie got off to a shaky start in his first full season, batting only .216 and stealing one solitary base through the Mets’ first dozen games. He wasn’t walking, he wasn’t running, he was just getting his feet wet. Fair enough, except someone I hadn’t given much thought to leading up to Opening Day was stealing bases and Mookie’s thunder like crazy. In that same stretch during which Mookie scuffled at the top of the Mets’ order, Tim Raines — batting in the same leadoff spot for another team — excelled. Over the Expos’ first thirteen games of ’81, Raines was a .380 batter, a .952 slugger and on base almost half the time. He had thirteen steals in his back pocket, or one for every game he’d played.

This, I reasoned, was what we were supposed to be getting from Wilson. The wrong rookie was shaping up as the Mookie of the Year. My impression was forged from an up-close perspective. The Mets and Expos faced off six times between April 18 and April 26. The Expos took five of them. Raines starred. Wilson didn’t. Mookie would have his day. Tim was having plenty of them early and often.

The days became the better part of a decade. The Expos didn’t necessarily live up to their Team of the ’80s projections, but Raines remained formidable, never somebody you wanted to see the Mets let get on base, for if he reached first, there was a good chance he was going to extend his trip to touch second, third and home. When he became a free agent after 1986, a bidding war for his services seemed a decent bet to break out. Pitchers and catchers couldn’t prevent Raines from running, but colluding owners cut down his options on the not-so-open market. Twenty-six major league franchises were suddenly run by true gentlemen who, my word, would never attempt to poach another team’s star, never mind that stars like Raines were supposed to be unencumbered by previous contractual obligations. The way things went, Raines couldn’t go anywhere, leaving him no choice except to go back from whence he came, which was Montreal, which happened to be in New York on May 2, 1987, the date of the first game he was eligible to play after a May 1 deadline redirected him back to the Expos.

Raines burst all over again onto the scene that Saturday afternoon, going 4-for-5 versus the Mets, the fourth of those hits being the grand slam off Orosco MLBN will be happy to cue up for you in case you require visual evidence of Raines’s excellence. It seems to be the only video that exists of Raines’s hitting skills.

I guess there are other clips out there. Raines played until 2002, by which time tape and digital technology presumably managed to capture a few other highlights of his. He left Montreal following 1990 and bounced around a bit as his production inevitably leveled off. To me he would always be the Mookie of the Year from 1981, mercifully removed from my eighteen-times-per-annum field of vision. Your divisional opponents can get on your nerves. The Expos got on my nerves in the era that Raines made them go. That’s a compliment. I’ve intermittently mourned the Montreal Expos since they morphed into the Washington Whatchamacallits, but constant opponents aren’t for mourning. They’re for spiting. I spite the Phillies, the Marlins, the Braves, the Whatchamacallits even. I spite the Cardinals, Cubs and Pirates when applicable for crimes committed to the Metropolitan psyche between 1969 and 1993. The Expos, due to their lack of existence, I tend to give a pass to.

Bygones should be bygone, even if you prefer Raines’s Montreal Expos weren’t. Defeats inflicted decades ago are irreversible. Life went on in 1981 and 1987 and so forth. Life stopped going on for the Expos and their fans in 2004. Who would root against a memory that won’t be coming to bat ever again? Spite has an honest place in a fan’s heart, but it shouldn’t overshadow our better angels.

Except the Expos live again through Raines stealing second and homering against the Mets over and over. Seeing him as he was in those contexts doesn’t touch off the best of my instincts. I may like and respect Raines and appreciate what his induction will mean to a group of partisans who’ve had nothing except memorialization of their memories to cheer since 2004, but I gotta tell ya: when I see Raines playing against the Mets the way I remember Raines playing against the Mets, I bristle as I did when Tim and his team were in their prime.

I’m enjoying disliking the Montreal Expos again. A Mets fan should dislike the Expos. Opponents are not to be cherished. They are to be, at best, grudgingly acknowledged for their splendor. They can also be detested. That’s what they’re for. That’s what the Expos were there for from 1969 through 2004, same as everybody else the Mets opposed in the National League East. When the Expos vanished from the face of the continent, the proper emotion to tap when they crossed the green fields of the mind was wistfulness. There were no more Montreal Expos. It was a sad state of affairs. They were a part of our lives several series a year for thirty-six years and brought spice and variety to our schedule. There was élan to playing the Expos, particularly visiting the Expos. There was something special.

Of course you’re gonna miss that. But what you don’t realize you’re missing is the enmity of opposition, of gritting your teeth and snarling and conjuring up whammies to stick it to those stupid Expos. It’s a skill set that no longer has any application, as pointless as raising a hackle at the sight of a Kentucky Colonels logo or having it in for the Ford-Dole ticket.

So, even if it’s just for a little while, in the immediate aftermath of Raines’s election and then again this summer when the scene shifts to Cooperstown, bring on the dormant notion of the hated Expos. Bring on the deep-seated resentment of a great player doing great things and how it made your innings miserable. It’s better to remember Expos for being Expos, not for being bygone.

***

Mookie Wilson, who had himself a fine career, was a Met in part because of the work of an outstanding scout, Harry Minor; Tracy Ringolsby explains their connection here. Minor also signed off on the drafting of Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, Wally Backman, Hubie Brooks, Kevin Elster, Kevin Mitchell and Gregg Jefferies, among others. On the same night Raines, Bagwell and Rodriguez learned they would be inducted into the Hall of Fame, I was in the audience for a fascinating discussion of baseball scouting, and the hightly entertaining speaker brought up Minor’s name, ironically for something Harry considered the worst miss of his long and distinguished scouting career. Minor watched a young Greg Maddux and reported back to the Mets that whatever his potential, he was probably a little too small to make it in the majors, so maybe the Mets shouldn’t select him in the next draft.

Oh well, you can’t win them all. On the other hand, you can’t win anything in baseball without men like Harry Minor skillfully deciphering talent. Minor was enormously important to the Mets as a scout between 1967 and 2011, encompassing the championships of 1969 and 1986, accomplishments that have Harry’s fingerprints all over them. The Mets honored him with their Hall of Fame Award the same day they inducted Mike Piazza into the team shrine in 2013, the last time the Mets held such a ceremony. You can be forgiven if you didn’t much notice Minor that Sunday. Piazza cast an enormous shadow and scouts tend to thrive where nobody else is looking.

Minor died on January 18, just as baseball was celebrating the newest class of Hall of Famers. Scouts don’t receive Cooperstown consideration. The shadows apparently stretch to Upstate New York that way. Yet there is no obscuring the results of the work they do. Harry Minor, who was in baseball one way or another for sixty-five years, forty-five of them with the Mets, helped provide us with some of our best days.

by Greg Prince on 9 January 2017 5:03 pm Friday night, as I was watching the Nets lose — an activity surely signifying the depths of winter for both me and the team to which I’ve clung through four post-Julius Erving decades as if I’m convinced the Doctor will be coming out of the locker room shortly to start the second half — we lucky viewers were enticed with the promise of even more Nets basketball, Nets and Sixers, at a special start time of noon on Sunday. I was thinking how that sounds awfully early for a basketball game, though I reasoned that once in a great while the Mets will play a makeup doubleheader on a Sunday starting at noon, and that would sound great right about now.

But there was to be no Mets baseball on Sunday, only more Nets basketball (another loss, which I forgot was in progress until the third quarter) and Giants football. There will be more Nets basketball imminently; January is lousy with the stuff. The Giants, having lost their playoff game in Green Bay later in the day, find themselves on hiatus sooner than desired, though it does clear their schedule for sailing and other tropical pursuits.

The Mets, meanwhile, are nowhere to be found.

The last we heard from them, the Mets were signing righthanded relief pitchers Ben Rowen and Cory Burns to minor league contracts. Ben Rowen is a submariner. Cory Burns is said to have a deceptive delivery. Actual submarines are supposed to be deceptive, but you can tell a submariner from a mile away. If only we were a mile from baseball season. Instead, it sits an eternity up the road.

Ben Rowen and Cory Burns, however they contort their arms in service to pitching, are nowhere in sight. Nor are any Mets doing any actual Met thing. Bring on the sidearming reliever. Bring on the unconventional reliever. Bring on somebody who can get somebody out. Bring on loaded bases and something to get out of.

This winter is endless. The next Met season’s gestation period is endless. It snowed on Saturday. There was no sense of baseball being blanketed. The Mets weren’t trading for George Foster or Johan Santana as they sometimes used to in the dead of winter. They weren’t even inviting Ben Rowen to camp. They already did that, just as they already preemptively directed Cory Burns to frolic among the minor leaguers. We got our big name taken care of weeks or maybe months ago. It’s hard to remember anymore. Yoenis Cespedes is in the fold, which is splendid. Everybody else who’s contractually bound to the Mets is very familiar. Nothing wrong with that. Cuts down on the awkward introductory phases.

Then there’s Ben Rowen, the submariner with twelve games as a Ranger and Brewer to his credit. Should he make the Mets, he might come through in the seventh inning and we will praise Ben Rowen. Or he might implode in the sixth inning and we will condemn Ben Rowen. We will have our Ben Rowen plot points on the graph of perception and adjust accordingly. But I’d love a look at Ben Rowen warming up about now. Or Cory Burns, who’s been a Padre and a Blue Jay, though neither lately. Last year Cory was a Lancaster Barnstormer, which is not to say he couldn’t make a fine New York Met if given the chance. Or a terrible New York Met if given the same chance. You know how relievers are, in that you never know how relievers are. Every member of your bullpen should sign the Hippocratic oath: first do no harm. Then have a colorful delivery, a colorful shtick, a colorful backstory of how you chilled on Justin Bieber’s yacht on your off day before entering the frozen tundra and not dropping the ball…I mean striking out Bryce Harper.

You remember relievers, don’t you? And starters? And baseball in general? This past weekend I’d have given all the Nets basketball (of which there’s a surfeit) and all the Giants football (of which there is none any longer) for a 12:10 doubleheader, or even a 1:10 single game.

Same deal all week. Go ahead, make me an offer.

by Jason Fry on 5 January 2017 5:08 pm The Baseball Equinox is behind us, meaning we’re closer to 2017 Mets baseball than we are to the 2016 variety — a comforting thought with the teeth of winter pearly and bared. But we still have 2016 Mets business to attend to, namely the offering of formal greetings to those who joined the orange-and-blue ranks in the season that most recently was.

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of matriculation: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Noah Syndergaard is Class of ’15, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or qualified as a Met ghost.

If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At the end of the year I go through the stockpile and subtract the maybe somedays who became nopes. (Circle of Life, y’all.) Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Your 2016 THB Mets! Enough with the throat-clearing. Here are your 2016 Mets, in order of matriculation:

Neil Walker: Replaced Daniel Murphy after Murph’s unexpected star turn in improv productions of “Damn Dodgers” and “Damn Cubs,” inevitably followed by the bringdown sequel that was “Damn Royals.” Y’know, for the first couple of weeks it looked like the jury was out on whether the Mets or Nats had got the better of their second-base switcheroo. But Murph kept up his MVP form while Neil returned to Earth and landed on the DL, felled by scary-sounding back surgery. Still, a good player and a decent soul who’ll be back for another go-round in 2017 because of a qualifying offer. Photoshopped Topps team-set card.

Asdrubal Cabrera: We were all wrong! And we loved it! Arrived with more warning symbols than the scary humming equipment caged in the basement — too old, can’t hit, no range — and made an excellent case to be the Mets’ MVP, carrying the team back into contention late in the year despite playing on one leg. His season’s exclamation mark was his thrilling extra-innings walk-off against the Phillies, a bit of punctuation punctuated by a bat hurl and arms shot skyward. Moments like that are why we keep watching years of 8-1 embarrassments, because you never know when … oh, just go watch it again. Serviceable Photoshopped Topps team-set card.

Alejandro De Aza: The best .205 hitter in baseball? Jaw-droppingly useless in the early going, when we speculated if the Mets were the victims of a truly odd hoax in which the same underwhelming guy kept showing up in Port St. Lucie in various disguises: was that De Aza, John Mayberry Jr. or Chris Young? With the Mets showing no inclination to send De Aza packing we all glumly accepted his presence … and he started getting hits that actually mattered, not all the time but often enough that we noticed, while filling in tolerably for the injured Yoenis Cespedes. If there’s a scale measuring Fan Reaction to That Guy Grabbing a Bat, De Aza managed to climb from Snarling Disgust to Apathy to Half-Willing Shoulder Shrug to Somehow I’m OK With This. You shouldn’t hit .205 for a whole season, but if you must, do it the De Aza way. Dopey Topps Heritage card, because the update set stuck him with a soul-killing horizontal. (WHICH THEY ALSO DID FOR WALKER AND CABRERA, AUGGGGHHHH STOP IT TOPPS STOP IT STOP IT.)

Jim Henderson: Returned from two years of shoulder woes and looked pretty good in the early weeks … good enough that Terry Collins treated him like a shiny new toy and re-destroyed his arm. Sigh. Topps Heritage card in which he looks like he knows that bright light ahead is, in fact, a train.

Antonio Bastardo: Arrived via what looked like a sensible two-year deal for a lefty reliever who’d been pretty good in Pittsburgh. And he was decent enough at first: witness his Houdini escape from bases loaded, none out in San Diego. But that was Bastardo’s World Series — after that he was so bad that we would have endorsed his being traded for Ramon Ramirez, Rich Rodriguez or a mad scientist’s failed experiment comingling tissue from Ramon Ramirez and Rich Rodriguez. This ended when the Mets sent Bastardo back to Pittsburgh … in return for addition-by-subtraction poster child Jon Niese. RECORD SCRATCH. Yes, Virginia, there is a less-desirable outcome than dumping a squishy, quivering mound of comingled tissue that was once Ramon Ramirez and Rich Rodriguez on the floor of a major-league clubhouse. Anyway, 2015 Topps card as a Phillie. Addendum re Niese: it’s not really fair to pin this on Bastardo, but in 2016 Topps gave the pride of Truculence, Ohio a) a Series 1 card as a Met b) a Photoshopped Pirates team set card and c) a redundant Update card as a Met. All of which my OCD required me to buy. Good God do I hate Jon Niese.

Rene Rivera: Being a Mets backup catcher is an interesting gig: you come out of nowhere, get a few big hits, are talked up as a replacement for the perpetually confounding Travis d’Arnaud, are a bystander as people point out such an idea is insane, and then get replaced by an essentially identical guy. Rivera broke the mold a bit, though, in ways both new- and old-school. He was a terrific pitch framer, a once-neglected skill that’s now been mainstreamed in front-office thinking, and he was a highly visible pitcher whisperer, ably talking balky hurlers through tough times with generally good results. Unexpected Topps Update card that saved him from a misspelled 51s card.

Matt Reynolds: In 2015 Reynolds made his bid for the kind of baseball immortality that nobody wants. He was added to the postseason roster but never appeared, making him provisionally the 10th Mets ghost in club history, the third to never appear in a big-league game for anyone else, and the first to achieve the additionally galling status of postseason ghost. Reynolds’ time in limbo proved brief, however, as he got the call in May 2016 and acquitted himself fairly well, playing multiple infield positions tolerably and getting some big hits. His best day by far came when he was summoned to Cincinnati, arrived after a sleepless all-night odyssey and responded with three hits, one of them a home run. That’s just a bit better than being a ghost. Bog-standard Topps card. He’ll take it.

Ty Kelly: Looking like an extra beamed in from an old Jimmy Cagney movie, Kelly arrived after the 2015 season with four previous organizations on his CV and one notable skill: the inclination to take a walk. That fit the Mets’ philosophy, and they sent Ty to Las Vegas, where he led the league in batting in the early going. That earned him a call to the big leagues, where the results were about what you’d expect from a rookie struggling with minimal playing time. Kelly took some walks, got a couple of big hits, but mostly sat on the bench. But hey, he made it, didn’t he? My cap is tipped. Yours should be too. Las Vegas 51s card.

James Loney: A flashpoint for Mets fans, who variously saw Loney as an empty hitter with head-scratchingly nonexistent range at first or a solid veteran bat with good hands. Seriously, blood was shed over this: we’ll always remember where we were when the James Loney Riot spilled out of the Mets Clubhouse store and into Bryant Park, necessitating Governor Cuomo calling out the National Guard and the Mets hustling in Rusty Staub to recreate his ’73 appeal for peace in our time. (Or maybe people were just shitty to each other on Twitter, but you remember it your way and I’ll remember it mine.) My take? Loney was better than either Eric Campbell or parking Lucas Duda out there strapped to a hand truck in a full-body cast. Still, points for his homer against the Phils on wild-card-clinching day and his not particularly restrained reaction. Inexplicably missing from Topps Update, so stuck with a subpar Topps Heritage card.

Brandon Nimmo: Sandy Alderson’s first draft pick arrived from the nontraditional baseball climes of Wyoming with a smile as wide as his home state. So far, Nimmo’s pattern has been to struggle at each new baseball level and then shine. It’s not clear where his playing time will come from in 2017, but it’s also a baseball truism that you usually wind up needing more outfielders and starting pitchers than you think. Should that be the case, here’s hoping Nimmo sticks to his pattern — or at least keeps smiling. Topps Update card in which he’s … wait for it … smiling.

Seth Lugo: Not so long ago Jacob deGrom — a pitcher our blog had mentioned exactly zero times during his minor-league career — arrived in New York and became a big star. It’s horribly unfair to start talking about Seth Lugo that way but also hard to resist, because Lugo was so unheralded that he made deGrom seem like Paul Wilson. That’s what happens when you’re the 1,032nd player taken in the draft and pitched for Centenary College. Anyway, although he was essentially Plan H for the Mets in terms of starting pitchers, Lugo arrived in July and rode a terrific curve to a significant role down the stretch. In some alternate universe the Mets are World Series champs and “Seth Lugo” is the new “Hey, y’never know.” This universe is different, but Seth Lugo still had a really good year. 51s card, for now.

Justin Ruggiano: Hit a grand slam off Madison Bumgarner in 2016. Did you hit a grand slam off Madison Bumgarner in 2016? 2015 Topps card as a Mariner.

Jay Bruce: What the actual fuck? It’s been a while, so I should just … no, I was right the first time. What the actual fuck? The Mets had a sound second-base plan in which Neil Walker would hold the fort while Dilson Herrera got a little extra seasoning instead of enduring a year answering questions about not being Daniel Murphy, then blew it up to acquire the kind of defensively challenged corner outfielder they already had too many of. Bruce then rewarded Sandy & Co. by playing like a wide-eyed rookie dropped into the center of a minefield and told to run sprints. Seemed like a nice fella, and his mild late-season resurgence was a relief, but what the actual fuck? Topps Update card.

T. J. Rivera: Murph, is that you? Rivera came up and hit a bunch, proved disinclined to take a walk, looked better than one would have expected in the field and played with a certain intangible but welcome moxie. Not a bad start. 51s card.

Gabriel Ynoa: Maybe the least memorable Met of the campaign. He pitched, which you need guys to do. Might pitch a lot more or might be the guy you miss on quizzes about 2016 Mets years from now. 51s card.

Josh Smoker: What’s in a name, anyway? Did Josh Smoker’s parents look down at him wriggling adorably in his cradle and say, “Josh is totally gonna come into baseball games late throwing fastballs?” (If this happened, by the way, it was when I was 20 years old. Please excuse me while I stick my head in the oven.) Smoker fanned a bunch of guys, but another bunch of guys hit prodigious home runs off of him. Still, perspective: Smoker flamed out as a Nats prospect and sank all the way to the indy-ball ash heap before beginning a phoenix-like resurrection that culminated with throwing heat for a big-league club. Light a cigar, Josh! Latest in our string of 51s cards.

Robert Gsellman: Forget the GEICO caveman, Gsellman was the real Jacob deGrom barroom fakeout. Though what got stuck in my head was that deGrom was Snoopy and Gsellman was Spike. I think this is funny and am going to keep referencing it until someone takes pity on me and acknowledges it as genius, or at least a good try. Anyway, Gsellman arrived as emergency relief after Jon Niese blew out his knee in St. Louis, pitched bravely in a game the Mets won, and proved gutsy and dependable during the unlikely run to a 163rd game. Good things sometimes do happen to the Mets. Some ancient Bowman card in which he has short hair and so could be anybody.

Fernando Salas: Most years feature a late-season deal or two in which a reliever shows up and is asked to haul sandbags to the riverbank posthaste. Sometimes this works out pretty well — Addison Reed, for instance. Sometimes it works out less than well — remember Reed’s THB 2015 colleagues Eric O’Flaherty and Tim Stauffer? With Salas it worked out pretty well. Between small sample sizes and the spaghetti-at-a-wall essence of middle relievers, you should conclude absolutely nothing from this. 2015 Topps card as an Angel.

Gavin Cecchini: The last guy standing at the dugout rail, Cecchini had two lonely at-bats in two weeks before being inserted in the 5th inning of a farcical 10-0 bombardment inflicted on the forces of good by the Phillies. If you were still watching, Cecchini collected a pair of doubles and was in the thick of everything as the Mets lost the damn thing, 10-9, but still left us feeling like they’d won something. Way to go, kid. 2016 Bowman card.

by Greg Prince on 3 January 2017 5:52 am We didn’t tweet in 1977, but if we had, I’m sure we would have assailed the year we lived in for being #TheWorst for taking from our midst so many beloved icons (and that’s not counting the baseball business conducted on June 15 of that year). Elvis died. Bing died. Groucho and his brother Gummo. Charlie Chaplin. Zero Mostel. Maria Callas. Toots Shor. Guy Lombardo. Joan Crawford. Eddie Anderson (Rochester from The Jack Benny Show). Sebastian Cabot (Mr. French from Family Affair). Diana Hyland (Dick Van Patten’s wife on Eight Is Enough and John Travolta’s true love in real life). Most of these people were transcendent, and they were all going at once.

We didn’t tweet yet in 2003, but we would have hashtagged ourselves into a mourning frenzy that September. Warren Zevon, John Ritter and Johnny Cash went in a four-day span; George Plimpton, Robert Palmer, Donald O’Connor and Althea Gibson joined them in the great beyond before the month was out. It was veritable celebrity carnage.

It’s not a contest, picking the year that packed the most attention-getting passings, but as much as we sadly shook our fist at 2016, it’s not like this sort of thing was invented over the past twelve months, though we certainly endured one of the most overwhelming onslaughts of morbid bulletins where people we’d heard of were concerned. I didn’t quite get why we as a culture faulted 2016 itself — it was a time period, not an actual grim reaper — but we do tweet nowadays, and the habit has led us to adopt and indulge strange customs and catchphrases before we’ve had a chance to road-test them for logic.

Death is a part of life, you might have noticed. Whether it touches us directly or from a distance, it touches off in us the impulse to remember. I believe keeping alive the memories of those no longer with us is a decent thing for the rest of us to do while we’re still here. It’s what I try to do when I pay tribute in this space to the recently deceased, whether I knew them intimately, casually or not at all but was moved by what they did while they were around.

With 2016 done doing whatever we decided 2016 did, I’m going to take a few minutes and remember some people who died in the past year, specifically those whose departures I didn’t get a chance to note here even though I’m sure I meant to. Baseball, predictably, is the thread that runs through them, but they weren’t all necessarily baseball people. I’m also going to throw in a name whose passing predates 2016 because it should never be too late to remember another human being…especially one who played for your favorite team.

***

On September 14, 1984, I had the Mets on my mind. Big surprise, I know. It was a Friday afternoon, and I was driving westbound on Interstate 4, the highway destined to become known at the I-4 Corridor, specifically the segment between Orlando and Tampa. This was early in my senior year in college, when I was the Board of Regents correspondent for my college paper. I had traveled from my campus, USF, to the campus where the BOR was meeting, UCF; did my reporting (dictating a story over a pay phone, as old-timey as that sounds); and now I was returning. The second-place Mets would soon be playing the first-place Cubs at Wrigley Field, beginning a three-game series that represented their last remote chance at possibly pulling out the division. It was a long shot, though. We stood 7½ out and had to sweep. There was a bar I’d pass on my way back to my off-campus dorm, the Copper Top. They had a sign in the window advertising the installation of cable TV and the broadcast of all manner of live sports, which was a pretty exotic proposition for an unwired college student in 1984. Maybe they had WGN. Surely they had WGN. And what other sporting event would they be showing on a Friday afternoon? Yeah, I’m definitely gonna swing by the Copper Top.

My train of determined Met thought was interrupted by the song that came on the car radio, probably from one of the Orlando stations, since they always seemed to be a couple of weeks ahead of Tampa. It was so bouncy, so effervescent, so captivating. I didn’t know what it was called, but I was instantly in love with its jitterbug!s, its boom-boom!s, its out-of-nowhere reference to Doris Day. What’s its name? “Wake Me Up Before You Go”? No, “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” by Wham…I mean, Wham! Repetition and exclamation fit a song that encompassed more energy in three minutes and fifty seconds than I did in a week. I never did stop by the Copper Top (preferring my bed because I decided I was running on fumes), but for the rest of the fall of ’84, I was so hyped up every time I heard “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” by Wham!, that I was left with little capacity to rue the Mets’ failure to catch the Cubs. How upset could someone be if he lived in a world onto which the sun was said to shine like Doris Day?

The group’s follow-up single, “Careless Whisper,” made clear the name of the half of Wham! who put the boom-boom into their sound was George Michael. It was inevitable that he’d plan on goin’ solo. Like the Mets of the mid-’80s, George would produce a ton more hits, many of them sparkling and spectacular. None, however, landed on the ear as viscerally or vivaciously as “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” which I count to this day as No. 30 on my personal Top 1,000 (and No. 1 among songs that greeted me in 1984). When I learned late on Christmas Day that Michael, my demographic contemporary, had died, my mind found itself speeding along I-4 once more.

***

The honor roll of musicians who left us in 2016 was, as has been documented elsewhere, staggering. Within that circumstantial supergroup is a subgenre of artists of parochial interest: those whose songs would become inextricable from the Met narrative. Glenn Frey’s “You Belong To The City” scored a montage of the Mets being every bit as big as New York itself in A Year To Remember. David Bowie’s “Changes” resonated through the difficult trades & transition period in An Amazin’ Era. “Volunteers” provided the backbeat to the scenes in which the 1969 Mets took over the world in the Eighth Inning of Ken Burns’s Baseball. The song was recorded by Jefferson Airplane and co-written by Paul Kantner.

Those gentlemen became associated by the Mets by use of their music. A singer just as famous a generation before them brought his talents to the Mets because he was a Mets fan. Julius La Rosa sang the national anthem at Shea often from the ‘60s into the ’90s, back when it was performed mostly on special occasions (otherwise, Jane Jarvis would play it on the organ or a canned recording would be used). La Rosa was synonymous with big days at Shea, including WNEW Day in 1975, when the Mets celebrated their affiliation with their flagship station. Julius had a second career in progress as a disc jockey at AM 1130, playing records from the pre-rock days when he was as big star in his field as Seaver and Kingman were in theirs.

***

Annually there is no bigger day in Flushing than Opening Day. Though I’d been watching and listening to Shea lidlifters since 1970 (and had my tickets turn into rainchecks in 1981), I didn’t attend a Home Opener until 1993. None of us among the 53,127 on hand had any idea what was in store for that season — it was all good on April 5. You believed anything was possible, especially when you saw who walked out for a special presentation. It was Dennis Byrd, a cause of Metropolitan Area concern the previous fall when he couldn’t rise on his own power from the slick Meadowlands turf, surfacing as the most hopeful sign related to power of positive thinking and proactive healing.

When Byrd went down in the rain against Kansas City after crashing into a teammate, he instantly became a former Jet defensive end, unable to walk. Rehabilitation was his next game. It proved successful. Though his football career was over, he was up on his own two feet (with the aid of a cane) to welcome the baseball season. The Mets invited Dennis to Opening Day and, as part of the pregame pomp, handed him Mets jersey No. 90, the same number he’d worn in green and white. “A Met for life,” he was deemed. The DE knew his way to Shea, which didn’t used to be anything unusual for New York Jets. He’d served as a Banner Day judge last August. He also knew his way into Mets fans’ hearts.

“If it rains,” he told the crowd on this indefatigably sunny afternoon, “we don’t have to play. And if I hit the ball over the fence, I get to walk around the bases. I can do that.”

***

The Mets wouldn’t exist had the Giants and Dodgers not abandoned New York, but some Giants and Dodgers stuck around long after those franchises made themselves scarce. The two men who gave the storied rivalry its signature moment were permanent Metropolitan Area fixtures for decades. Bobby Thomson remained on the scene until his death in 2010, leaving Ralph Branca to carry forward the legacy of The Shot Heard Round The World. That Branca was on the wrong end of the most legendary home run ever hit did not hold him back from embodying baseball history, even if it went against him. He was the ultimate good sport in the company of Thomson, the most supportive of teammates to rookie Jackie Robinson, the knowing father-in-law of Bobby Valentine and even the Met pre- and postgame radio show partner to Howard Cosell in 1962 and ’63. Kids like me would see Branca on Old Timers Day and understand that baseball didn’t begin with the Mets.

An adult like me encountered him once. I was behind him at the sign-in table for a press luncheon years ago. Next to his name, where we were asked to list our affiliation, Ralph wrote “BASEBALL”. I thought that covered it quite comprehensively and accurately. (So does the writeup of someone who knew him well — please see what Matt Silverman had to say about his old friend in his entry of November 24.)

***

I’m fond of saying that I’m a New York Mets fan in my heart and a New York Giants fan in my soul, reflecting a deep affinity for the team that represented the city’s National League interests for 75 years, right up until five years before I came along. If the 1883-1957 portion of my soul had a facilitator, it was Bill Kent, founder and guiding light of what became known as the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society, which was a splendid name, but I’ll always remember our little group as “the guys,” which is how Bill referred to us when we first took shape.

Bill did it all for “the guys,” no matter how few or how many we numbered on a given day. Membership fluctuated from the time he first called me in 2004 to invite me to a meeting, having inherited a list of phone numbers from a predecessor organization nobody committed to keeping organized. That was not a responsibility that eluded Bill, a loyal Giants fan who rooted without pause from Mel Ott to Madison Bumgarner, coastal relocation notwithstanding. He was always reaching out, getting “the guys” together whenever and wherever he could find adequate space. A grudging user of e-mail, Bill preferred to call individually with date and locale for our next caucus. I looked forward to picking up the phone and hearing a gravelly voice greeting me with “rackadoolie!” I just assumed it was Bill’s version of “23 skidoo!”

We followed the bouncing Bill from the far West Side of Manhattan to Riverdale to Kingsbridge. He was the gray tornado, disheveled enough to worry you that he wouldn’t remember we were assembling when he said we would, sharp enough to book speakers, order pies and make sure everybody got seconds. When he was up for driving, he’d offer to pick you up from the Spuyten Duyvil train station or drop you off at the 231st St. stop on the 1 line. If you were concerned about traveling from relatively far away, he’d play transportation matchmaker. In between, he’d be happy to tell you about the time at the Polo Grounds that his childhood chum Little Lenny sparked Ernie Lombardi’s ire by taunting him about how slow he was (according to Bill, Ernie was too torpid to effectively chase Lenny down). Bill shepherded us as we grew from a handful of diehards and historical fetishists to a vibrant social club that attracted the attention of WFAN, The New York Times and the San Francisco Giants. Bill made the Giants aware of us and they included us on the New York leg of their three world championship tours.

Eventually, a difference of opinion regarding operating philosophies led to a breakaway group that ultimately proved more popular (and it is definitely a swell bunch), sending Bill’s guys back to meeting in the smallest room a Bronx church had to offer. He was still the essence of servant-leadership the last time I saw him, in the spring of 2015, wrangling our proceedings to informal order; pulling straws from his raincoat pockets in case anybody wanted one for the sodas that came with our pizza, urging us to buy one of our guest speaker’s books; asking our speaker if he could give the guys a break on the price; and forever passing around a sheet of paper to make sure he had everybody’s contact information.

The Nostalgia Society became a thing of the past soon after. Membership received an email from his son explaining that because of health issues, Bill, like the team he loved, had moved from New York to California. The kicker was his destination was Southern California, though we were assured being around all those Dodgers fans wasn’t going to alter Bill’s allegiances one bit. No doubt they stayed solidly orange and black to the end, which, I eventually learned, came October 6, one day after the 2016 National League Wild Card Game, a most unfortunate affair for us Mets fans, but boy do I hope Bill got to see his team win one last game. He deserved to go out a winner.

***

James Loney hit his first home run as a Met on the same day Muhammad Ali died, the juxtaposition of which won’t necessarily mean anything to you, except it got me to thinking about names. Ali changed his as an adult from Cassius Clay. It was a defining element of his biography. And what does this have to do with James Loney? Nothing, exactly, except as I got used to Loney being a Met, I wondered, in the vein of Ali vs. Clay, why he was James and not Jim. I remembered two decades before that somebody I worked with telling me about a conversation with a man named James, a person with whom he had never spoken before. My colleague, capable of being one of these overly familiar sorts, calls him up and says, “Hi Jim,” only to be told “there’s nobody named Jim here.” This guy was James, and you were to address him as James. Since then, I have known Jims who didn’t go by James, Jameses who didn’t go by Jim, a couple of Jimmys who were pretty free and easy about the whole thing…and one semi-complicated case.

During the Jerry Manuel era, a fellow named Jim dropped us a line here at Faith and Fear to ask if we would link to a Met story he wrote somewhere. Sure, I said. And we did. We said, in so many words, check out this article by Jim. He expressed gratitude, but added, “One more favor, at the risk of my sounding like a numbskull: Could I ask you to put James (Middle Initial and Last Name) in parentheses, where you list Jim at the link? I actually prefer both names being listed that way, so — only if it’s no bother — that would be perfect.”

It wasn’t a bother, and I assured him he wasn’t a numbskull. It came up a couple of more times over the years. He’d ask for a link, I’d say no problem, Jim, do it and then I’d be asked, hey, could that be James, not Jim? Again, I complied, but since he seemed to go by Jim in real life, I didn’t know what the big deal was. I wasn’t calling him Cassius.

The confluence of Ali’s death and Loney’s arrival made me think of Jim/James a little…and then a lot, because that very same weekend in early June came word that he had died. It didn’t come as a total surprise, since I had seen on Facebook that he had recently been hospitalized, but it was still a shock. He was in his mid-fifties, though you might say he had an older soul. Jim seemed to enjoy giving the impression he went way back — even further back than guys our age already do. If it made him happy, so be it. Ditto for his habit of calling me seeking information that the rest of civilization could and would easily Google. The exchanges would inevitably start something like this:

“Hello.”

“Hello Greg, this is Bob Murphy,” said in a voice that didn’t sound very much like Bob Murphy. “How about those Amazing New York Mets?”

“Hey Jim, what’s up?”

“No, this is Bob Murphy.”

“Uh-huh. Hey Bob.”

After asking how authentic I found his Bob Murphy impression and not quite believing I didn’t find it fully convincing, he got to the ostensible reason he called, which was to obtain a data point that allegedly only I could deliver at that moment. He was writing something, see, and he couldn’t remember this or that, and he just knew I would know. Maybe he also wanted to let me know that he’d read something I wrote the other day and he really liked it. From there, he’d instigate a debate on some recent roster move, almost always encompassing an insistence on his part that Nick Evans never should have been let go. There’d be an accusation that some local columnist or broadcaster was using his material without crediting him, and he’s not mad or anything, it’s just that it would be nice if he’d been properly sourced (he was indeed a solid writer). Oh, and there was a problem with an editor who cut the best part of a story. There was a mention of some really old movie that he’d hoped I was familiar with so we could talk about that. And Shea Stadium ushers — he was fonder of them on the whole than I was and proceeded to tell me yet again about one of them now working at Citi Field who was telling him how they were all getting screwed over by management. And you know what he really enjoys eating when he goes to a game? Why, the Premio Italian Sausage, of course. It was his favorite at Shea and it’s his favorite still.

“Hey, do you think I should go to the day game next week?”

“I don’t know, Jim. If you want to go, go.”

Under whatever name he preferred, Jim/James was reaching out, and not in that empty corporate way the phrase implies. He was reaching out for another person, for a connection. Somewhere along the way, he decided I’d be the person he’d reach out to where the Mets were the subject. He was a Mets fan. I was a Mets fan. In theory, it was the basis for a relationship. I tried to reach back. In all honestly, I didn’t always have it in me to meet him halfway. But maybe the Mets did give up on Nick Evans too soon.

***

Ziggy also died last spring, a little before Muhammad Ali and Jim/James. Another unwelcome Facebook dispatch. I never heard the cause of death. Ziggy was my classmate in Hebrew School, an acquaintance through elementary school, a lockermate in seventh grade and a constant presence on the periphery of my life until I graduated high school. Ziggy, who lived a few blocks from me, and I were heading to Shea Stadium separately on July 17, 1976, but when his dad saw my sister and me walking toward the train station, we were invited into their family stationwagon (a.k.a. the Ziggymobile) and offered a ride. My sister was wary, but I vouched for the Ziggys’ collective character, having been over to their house once and emerging unscathed. We arrived at Shea in fine fettle but Suzan declined Ziggy’s dad’s invitation to meet afterward for a ride home.

Ziggy had a more traditional first and last name, but à la Cher and Madonna, he didn’t need them. For as long as I could remember, nearly everybody called him Ziggy, and he seemed to go with the flow, just as I did when Ziggy pulled his signature move of walking up to me, no matter the situation, and telling me, in his low deadpan croak, “Shut up, Greg.” He even signed my yearbook that way.

***

You might have heard Chris Cannizzaro, one of the Original Mets, died last week. Caught for the Mets from 1962 through 1965, played in the majors clear through 1974. Casey Stengel referred to him as a defensive catcher who couldn’t catch. Casey had a way with words, but Cannizzaro surely proved himself a big league survivor. Not until Ramon Castro returned for a fifth season of backup duty behind the plate was Chris bumped from the Top Ten list for most games caught by a Met. He ranks thirteenth to this day.

Did you hear Phil Hennigan died in June? If you did hear, word almost certainly didn’t reach you until September. Just because a person was well-known a while back, it doesn’t keep him in the limelight forever after. Phil was living his retirement in Texas. That’s where he passed on with relatively little notice outside of his community. That’s how it goes for most of us.

We know Phil Hennigan from his stint as a Met in 1973, which is to say he was a member of the National League champions, albeit before they were champions. In 30 games between April 11 and July 7, the ex-Indian reliever compiled an ERA over 6 and trudged around a record of 0-4. The righty was demoted to Tidewater and never pitched in the majors again. Hennigan became the first Met to end a season with no wins and that many losses since Sherman “Roadblock” Jones in 1962. On the other hand, Phil did record three saves, and given that the Mets won the East by a mere game-and-a-half in 1973, well, You Gotta Believe every little bit helped.

***

Every time the Mets score an absurd amount of runs and you reflexively place tongue in cheek and ask, “Did they win?” think of Dick Smith. The game — Mets 19 Cubs 1 — from which the old Met chestnut that somebody called a newspaper to ask how many runs the club scored that day and then incredulously asked if they had managed to prevail sprung was earned to a great extent on Dick Smith’s dime. That afternoon of May 26, 1964, at Wrigley, Dick’s bat put the boom-boom into the Mets’ attack, recording three singles, a double and a triple. It was the first five-hit game in Mets history. He scored three and drove in two, having himself the kind of afternoon Kirk Nieuwenhuis enjoyed just before the All-Star break in 2015 when Kirk became the first Met to hit three homers in a home game.