The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

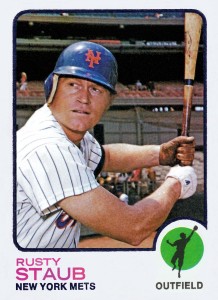

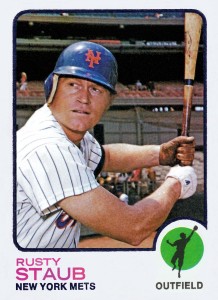

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 3 March 2016 3:24 pm Terry Collins said the other day that “fun time” is over. I hate to disagree with the manager of the defending National League champions, but I’d say fun time is just getting started.

Collins was referring to the Yoenis Cespedes Off-Hours Charismatic Carnival, which, to be fair, was loads of fun. More fun than:

• a barrel of profiles of longshot candidates to be the last man out of the bullpen;

• endless speculation over how many games the stoic, stenosisic Captain might play;

• another round of thoughts from Neil Walker regarding how different New York might be from Pittsburgh;

• and whatever else would have filled our field of vision once the adrenaline rush of confirming New York Mets baseball players were going about their business in Port St. Lucie, Florida, inevitably wore off.

Yoenis made the deadliest week on the baseball calendar come alive (save for a pig who used to be alive). There were the sweet, sweet rides that gave conspicuous consumption a good name. There was the equine entrance that proved Noah Syndergaard makes for a more comfortable sidekick than Chris Christie. There was that bit Carnac came back to deliver with Ed McMahon.

“Trains and boats and planes.”

“Trains and boats and planes.”

“Name the only three ways Yoenis Cespedes hasn’t come to camp in the last week.”

“HIYO!”

Hi Yo, indeed. He was an international man of mystery behind the wheel. He was a rootin’, tootin’ sight up on his high horse. He was a Western-style presence when he went whole hog. Oh, the butcher and the baker and the people on the streets — where did they go?

Well, we know the butcher went to meet Yoenis’s not-so-little piggy, who cost our Most Visible Player seven-grand, or what probably accumulates on the many passenger seats of the Yoenis fleet. At that rate, I was hoping Piggy would trot out alongside Ces before the Home Opener, wearing a matching No. 52 and four or five neon-green sleeves (including one for the tail). Instead, he’s slated to be the guest of honor at a future roast. Somewhere Foster Brooks is clearing his throat and, perhaps, his glass.

Will the pig become links by breakfast tomorrow? Will the player be on the links by nightfall? (He likes to golf, you know.) These were the questions that preoccupied us when there was nothing else to think about. The word spread of Yoenis the Kid, and for that we were grateful. Now it’s vaya con dios vaquero, hello five-tool superstar. You and your pals can go commit some baseball now.

Real Fun Time 1.0 commenced at 1:05 Thursday afternoon, and it will be in effect until the required system upgrade kicks in on April 3. The New York Mets were on the air on WOR, featuring some guys we’ve all heard of, some other guys we’ll hardly hear of again. The first voice of spring we actually needed to hear from was Josh Lewin’s. He welcomed us to baseball, choosing to channel word of Terry’s down-to-business declaration through Richard Jenkins’s exasperated Dr. Robert Doback in Step Brothers, because that’s how Josh rolls. “Rumpus time,” Lewin aptly quoted, “is over.”

Last week, there was so much room for activities. From this week forward, there’s only one activity worth our attention. Play ball.

by Greg Prince on 29 February 2016 10:04 am The Oscars were handed out Sunday night. Thus, per Monday morning-after tradition, the Academy pauses to remember those Mets who have, in the baseball sense, left us in the past year.

ERIC GEORGE O’FLAHERTY

Relief Pitcher

August 5, 2015 – September 25, 2015

Ronnie seemed to catch himself and tried to walk his presumptuousness back, but it was too late. The win wasn’t in the bag and the cat was out of it. Here came the stupid Marlins. Here came an unexpected flurry of Met relievers. Eric O’Flaherty quickly wore out his welcome by allowing hits to four of five batters to open the ninth. It was only 8-2 when Collins hooked him. No biggie, right? We’d learned our latest LOOGY maybe should be limited to one batter, like he was in the eighth.

—August 6, 2015

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Pirates, 2/11/2016)

TIMOTHY JAMES “Tim” STAUFFER

Relief Pitcher

September 13, 2015 – October 1, 2015

He was better than Eric O’Flaherty, OK?

—December 28, 2015

(Free agent, 10/14/2015; signed with Diamondbacks, 12/11/2015)

JOHN VICTOR “Jack” LEATHERSICH

Relief Pitcher

April 29, 2015 – June 20, 2015

They had survived Jack Leathersich’s learning curve and would survive Bobby Parnell’s creakiness. All they needed to make a day of it was to survive the ninth. They didn’t.

—June 14, 2015

(Selected off waivers by Cubs, 11/19/2015)

WILFREDO JOSE (Soto) TOVAR

Infielder

September 22, 2013 – September 28, 2014

Yeah that thing happened in the fifth, and it was important in the context of a game in which only one run was scored and it wasn’t scored by Hamilton or any Red. It scored only because Wilfredo Tovar — a high-profile personality compared to Juan Centeno — was kind enough to get hit by Mat Latos, move along to second on a Matsuzaka bunt, take third when Latos threw a pitch that eluded the grasp of Devin Mesoraco (speaking of names that loiter in the back of your baseball awareness) and dash home when Eric Young broke his bat to produce the tricklingest of grounders that snuck into right through a drawn-in Red infield. The Mets went up, 1-0, in the third without anything that could be remotely mistaken for a component of an offensive attack and Matsuzaka, Feliciano and LaTroy Hawkins made it stick.

—September 25, 2013

(Free agent, 11/6/2015; signed with Twins, 12/14/2015)

ALEXANDER JESUS “Alex” (Matos) TORRES

Relief Pitcher

April 9, 2015 – July 29, 2015

Alex Torres, odd hat and all, struck out Yelich. It was like he did so in slow motion. The bat slipped from Christian’s hands on his swinging third strike, leading to an instant where the entirety of Metsopotamia stared in horror before recovering to confirm, “he’s out, though, right?” Yes, he was out. The signal was made; the pyrotechnics, such as they are, could be loaded; and the Mets couldn’t be stopped. It wasn’t as easy as we might have suspected, but Dee Gordon wound up sleeping with the rest of the Fishes. As bedtime Torres go, Alex gave us a pretty nice one.

—April 19, 2015

(Free agent, 11/6/2015; signed with Padres, 1/7/2016)

DARRELL ALBERT CECILIANI

Outfielder

May 19, 2015 – July 5, 2015

Darrell Ceciliani homered in the bottom of the fourth to make it 8-4. It could have been taken as a tease or it could have been interpreted as a surmountable score. One out later, the surmounting continued apace when Dilson Herrera went deep. Being down 8-5 isn’t easy, but it’s not crazy, not when you’re facing Foytack-Lemanczyk.

—June 15, 2015

(Traded to Blue Jays, 2/2/2016)

SCOTT ADAM RICE

Relief Pitcher

April 1, 2013 – June 8, 2014

Second crown jewel: ninth inning; the wind kicking up Dave Howard’s memorial good-time garbage; and entering our conversation for the first time in a Mets uniform, Scott Rice. Many have left Citi Field in deference to the hour, the score and recurring chill (because luxuriating in a ninth-inning, nine-run blowout is apparently a hassle), but this is a treat for those of us who have stayed. Scott Rice, drafted into professional baseball so long ago that Bobby Bonilla was on the Mets payroll not as a running joke but as a pinch-hitter, is making his major league debut. His uniform pants are billowing in a bitter gale. His crowd can be better described as a gathering at this point. These circumstances resemble a hopeless September afternoon more than the one day of the year the Mets tend to be perfect, but would you tell Scott Rice this is anything other than ideal? We wouldn’t. So Joe and I and hundreds of others stand and applaud as he’s announced. Or, more or less as Steve Zabriskie greeted Gary Carter on a similar occasion 28 years earlier, “Welcome to New York, Scott Rice!”

—April 5, 2013

(Free agent, 11/6/2015; signed with Diamondbacks, 12/14/2015)

JOHN CLAIRBORN MAYBERRY, Jr.

Outfielder

April 6, 2015 – July 24, 2015

When Eric Campbell doubled with two out in the top of the eighth to raise his batting average to a rousing .177, I thought maybe we weren’t done. John Mayberry came up and I really began to imagine crazy things. Didn’t Mayberry hit a home run here in April? Doesn’t Mayberry have some kind of track record that made him appealing enough to sign in the offseason? Aren’t there fairies flying through the air who watch over babies and puppies and kittens and baseball teams with adorable baseball-headed mascots? Yeah, I was carried away with the Mayberry fever.

—June 22, 2015

(Released, 7/30/2015; signed with White Sox, 8/7/2015)

MATTHEW G. “Matt” den DEKKER

Outfielder

August 29, 2013 – September 28, 2014

How could this not work? And when EY takes second, how could this not work right away? Well, it didn’t. It found a way not to. Campbell bounced to Ian Desmond, who threw to Wilson Ramos, who kept a couple of his toes on the foul line, which had nothing to do with anything except for some murky rule nobody understands and can be interpreted differently depending on the time of day. In San Francisco Wednesday afternoon, a similar play penalized the catcher. In Flushing Wednesday evening, den Dekker was out by a mile and several hours. Terry Collins — reportedly destined to manage the Mets long after Bud Selig is done commissioning baseball — attempted to litigate the call, but Chelsea Market’s night crew wasn’t moved to overturn.

—August 14, 2014

(Traded to Nationals for Jerry Blevins, 3/30/2015)

ERIC ORLANDO YOUNG, Jr.

Outfielder

June 19, 2013 – September 28, 2014

September 1, 2015 October 1, 2015

In the bottom of the seventh, with two men on, Wright recreated his long-ago hit over Johnny Damon’s head at Shea for a double. It scored Eric Young, Jr. (who now has four at-bats as a ’15 Met, six runs scored and no hits — pretty much the way one should use Eric Young, Jr., in baseball games), and it would have scored Curtis Granderson except it hopped into the stands.

—September 15, 2015

(Free agent, 11/5/2015; signed with Brewers, 1/5/2016)

VICTOR LAURENCE “Vic” BLACK

Relief Pitcher

September 2, 2013 – September 13, 2014

Everybody’s on, nobody’s out, Ryan Sweeney’s up and he hits the ball…real hard. At Niese. Who shields better than he fields. The ball bounces off Jonathon as Arismendy scores. Now it’s 7-3, the threat is grave and the group slated to play after the game is practicing their dirges. In comes Black. The word is he doesn’t allow inherited runners to score — not on his watch. But, oh what an unwanted bounty of inherited runners! Suspicious scions blessed with great fortunes have hired lobbyists to protect less. But Vic Black will not be heard demanding a repeal of the estate tax. He simply goes to work, inheritance be damned.

—August 17, 2014

(Free agent, 11/6/2015; currently unsigned)

ANTHONY VITO RECKER

Catcher

April 7, 2013 – September 27, 2015

Shocking as it may have been to behold, Bartolo Colon doubling in Anthony Recker was less surprising than Ruben Tejada emerging as the Mets’ full-time third baseman. Anthony Recker being on second for Colon to double in was rather stunning in and of itself — Recker was 0-for-13 at Citi Field before he bottom of the second Sunday, whereas Colon was 1-for-8 — but not as surprising as Tejada being anointed permanent as can be caretaker of the position that was supposed to be taken care of through 2020. Anthony Recker played third base for the Mets before Ruben Tejada ever did and Anthony Recker is a backup catcher. No wonder Colon connecting for extra bases seems the least surprising aspect of Sunday’s win over the Marlins.

—June 1, 2015

(Free agent, 11/6/2015; signed with Indians, 11/27/2015)

TYLER LEE CLIPPARD

Relief Pitcher

July 28, 2015 – October 31, 2015

Lucas Duda ensured there’d be enough runs when he launched, blasted and rocketed — the more verbs the better — a baseball deep into the Big Apple or Apple Reserved or Apple Orchard section, whatever it’s called these days, to stake Noah to an early 2-0 lead. Curtis Granderson removed any ancillary offensive worries with a two-run shot of his own late. Tyler Clippard made us think of him as a helpful Met pushing us along rather than an old nemesis waiting to explode in our faces by keeping the ninth as tidy as it needed to be.

—July 29, 2015

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Diamondbacks, 2/8/2016)

KELLY ANDREW JOHNSON

Infielder

July 25, 2015 – November 1, 2015

Fifteen years later, on another Saturday in late July, the name Mike Bordick came up in idle conversation before that night’s Mets game. It wasn’t in a complimentary vein. A few hours after that, without any irony whatsoever, I leapt to my feet to applaud the first Met home run hit by Kelly Johnson in his first game as a Met. He was traded for on Friday. On Saturday, he and his fellow erstwhile Atlantan Juan Uribe went about transforming the Mets from frauds into legitimate contenders. At least that’s how I decided to see it from Section 329, where you could barely see anything that didn’t look like a pennant drive for the ages taking shape.

—July 26, 2015

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Braves, 1/8/2016)

JUAN CESPEDES (Tena) URIBE

Infielder

July 25, 2015 – October 30, 2015

This is Juan Uribe singling in Lagares and me going about as nuts as I did all night. I’d missed Juan Uribe. We had no righthanded bench without him. Without him, that at-bat would have been Michael Cuddyer’s. I’ve been trying very hard to be very supportive of every Met this postseason, but Cuddyer is not who I wanted up in that spot.

—October 31, 2015

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Indians, 2/28/2016)

MICHAEL BRENT CUDDYER

Outfielder

April 6, 2015 – October 27, 2015

I was wrong to have expected the 11:02 from Jamaica to have left Jamaica at 11:02, so my last call of Thursday night was off (forty sweltering, cranky minutes of waiting later, I realized there’s a reason the LIRR never touts the train from the game). Otherwise, though, I had a pretty good run of getting things right. Most pertinently, my announcement to my new buddy Skid — more on him in a bit — as the bottom of the ninth unfolded that Cuddyer was gonna win it for us came off as extraordinarily prescient. It was, technically, but not really. I went with Michael as our potential savior of the moment because we needed one run and he was going to be the fifth batter, and if I learned anything across consecutive nights at Citi Field, it’s that the Mets seem to require at least five plate appearances to generate a single meaningful tally.

—June 12, 2015

(Retired, 12/12/2015)

CARLOS EPHRIAM TORRES

Relief Pitcher

June 16, 2013 – October 3, 2015

Nobody has been a fully active current Met longer than Carlos Torres. […] He may not move mountains and he hasn’t worked many miracles, yet the Mets keep him like an oath. It may not be the most unshakable of active-duty tenures ever — I believe Tom Seaver was an irresistible roster force between April 11, 1967 and June 15, 1977, never going on any kind of list until “TRADED” came regrettably along — but it does defy Met intuition. In the come-and-go world of Major League Baseball, an institution Torres departed in 2011 so he could pitch in Japan, middle relievers are quickly replaceable cogs. One doesn’t quite work the way you want it to, get rid of it and grab another. It’s not like there isn’t a surplus of Burkes and Atchisons, let alone O’Flahertys, rattling around the bottom shelves of waiver wires everywhere. Then again, when you get somebody really special, somebody who almost always gets the job done, somebody you can regularly rely on…Carlos Torres? That doesn’t exactly sound like Carlos Torres, does it?

—September 5, 2015

(Free agent, 2/1/2016; signed with Braves, 2/11/2016)

KIRK ROBERT NIEUWENHUIS

Outfielder

April 7, 2012 – May 18, 2015

July 6, 2015 – October 31, 2015

You don’t gotta believe, but if you can legitimately say you saw (or heard) Kirk Nieuwenhuis homer three times in one game, then you can’t say anything where these Mets are concerned is impossible.

—July 13, 2015

(Selected off waivers by Brewers, 12/23/2015)

ROBERT ALLEN “Bobby” PARNELL

Relief Pitcher

September 15, 2008 – September 30, 2015

Finally, with the lead still 2-0 (because who needs more runs anyway?), it was Bobby Parnell in for the save, and am I crazy, or has Parnell actually become something akin to a dependable closer? I was going to say “lights-out closer,” but I figured that’s asking for trouble from the bullpen gods. However one measures Parnell’s effectiveness, it was in effect. The ashes of the Nats’ hopes scattered into the ninth-inning wind in order.

—April 22, 2013

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Tigers, 2/19/2015)

JENRRY MANUEL MEJIA

Relief Pitcher

April 7, 2010 – July 26, 2015

So in comes Mejia, whose previous six outings each merited an “S” in the box score. On SNY, it was mentioned that the last Met closer to streak that efficiently was Billy Wagner in July of 2008 (no great shakes before that sudden spurt of spectacularity, Billy would pitch three more times and then be shut down for the season, setting up that year’s bullpen for exploits likely still inducing nightmares in particularly skittish Metsopotamian precincts). Mejia was seeking his seventh save in seven consecutive outings. The last Met closer to do that? I don’t know. I assume either Jesse Orosco or Jesus Christ.

—July 28, 2014

(Permanently suspended from Major League Baseball, 2/12/2016)

DILLON KYLE GEE

Starting Pitcher

September 7, 2010 – June 14, 2015

It’s not so much that I expect Gee — potentially a postmodern Rick Reed in terms of command — to make a habit of going 7⅔ and allowing no runs on almost no hits. It’s that a player who could help the Mets in the near term was retained, and another player who wasn’t helping at all was demoted. Gee would have likely wound up back here eventually because of Young’s bum shoulder, but it was sensible as salmon to keep him around in the interim. Ideally, you might want a kid like Gee starting somewhere, like Buffalo, every fifth day rather than being subject to uncertain use in the Met bullpen, but as we’ve learned over and over, the Mets do not operate in an ideal world.

—May 19, 2011

(Free agent, 10/5/2015; signed with Royals, 12/14/2015)

JONATHON JOSEPH “Jon” NIESE

Starting Pitcher

September 2, 2008 – November 1, 2015

Niese is a terrific trade candidate on a team with a surplus of starting pitchers. I’d argue that contract makes him the best trade candidate on the staff once you subtract the guys the Mets would be obviously insane to move. (Why on earth would you trade Zack Wheeler, who has a higher ceiling and seems a lot more motivated to learn and improve?) If you made me GM for a day, Niese is the pitcher I’d ship out of town for that additional bat the Mets so desperately need. Maybe some other staff ace can convince him of the importance of doing his homework. Maybe some other pitching coach can get him to think about what to throw. Maybe some other manager can teach him to cover first base all the time instead of sometimes.

—August 7, 2014

(Traded to Pirates, 12/9/2015)

DANIEL THOMAS MURPHY

Infielder

August 2, 2008 – November 1, 2015

For those of you who are Daniel Murphy (.529, a home run every night), thank you. For those of you who are Daniel Murphy’s teammates, what’s it like knowing Daniel Murphy? It must be an incredible sensation to be near that much greatness every day. If you’ve touched Daniel Murphy, can we touch you? By all means apply some Neosporin first, because if you’ve touched Daniel Murphy, you’re probably going to need to salve those burns. No baseball player has ever been hotter than the 2015 NLCS MVP. Murphy, a Met since 2008, didn’t do it alone. But you had the sense he could have had it been necessary.

—October 22, 2015

(Free agent, 11/2/2015; signed with Nationals, 1/6/2016)

by Jason Fry on 23 February 2016 5:51 pm On February 17 we lost not one but two Mets.

There was no shortage of farewells for Tony Phillips, who died in Scottsdale, Ariz., at 56. And that was to be expected — Phillips racked up 2,023 hits over an 18-year career.

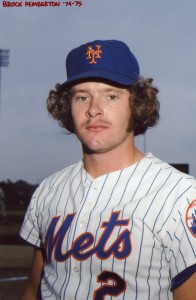

Brock Pemberton was the other Met who died on Feb. 17. His death at 62 in Ardmore, Okla., went largely unremarked in baseball circles, which also wasn’t unexpected. After all, Pemberton collected 2,019 fewer big-league hits than Phillips. His pro career spanned eight seasons, with a ’74 cup of coffee in New York and the merest sniff at one — two games, two at-bats — the next year.

But as I learned making baseball cards for obscure Mets, even agate-type careers contain interesting stories. Pemberton’s dad Cliff was a Dodger farmhand in the late 1940s and early 1950s, hitting for a high average without much power. His son was born in Oklahoma but blossomed at Marina High in Huntington Beach, Calif., where the Pembertons had moved in ’68. (Marina High later produced Kevin Elster.) The Mets drafted Pemberton in ’72 and he turned out to be a lot like his dad — a spray hitter who made solid contact without clearing too many fences. Cliff played second base, but Brock was a first baseman — a slightly speedier Dave Magadan.

Pemberton’s breakout season was ’74, when he hit .322 with 89 RBI for Joe Frazier‘s Victoria Toros. After the Toros wrapped up the Texas League title, Pemberton learned he’d been granted a September call-up to the Mets. He struck out as a pinch-hitter against the Expos on Sept. 10, but more, well, amazin’ events were in store.

A day later, a 3-1 Met lead evaporated against the Cardinals in the ninth, setting up one of baseball’s all-time marathon games. In the 25th inning St. Louis grabbed a 4-3 lead when Hank Webb picked Bake McBride off first (balking in the process) but hurled the ball down the line; McBride ran through the third-base coach’s stop sign and was out from me to you. Well, at least he was until Ron Hodges dropped the ball.

In the bottom of the 25th, fly balls by Ken Boswell and Felix Millan left the Mets down to their last out. It was after 3 a.m. Yogi Berra sent Pemberton up to the plate, and the rookie nearly decapitated Sonny Siebert for his first big-league hit — almost certainly the first big-league hit seen by the fewest people in Mets history. (John Milner then struck out.)

Pemberton collected three more hits in September, had a brief call-up in ’75, and then was traded to St. Louis with Leon Brown for Ed Kurpiel after the 1976 season. 1980 was Pemberton’s final year in pro ball, and saw him serve as the 26-year-old player-manager of the Macon Peaches. After leaving baseball, he lived in New Mexico, working as a landscaping supervisor for state parks, Indian reservations and colleges.

His obituary is filled with family recollections and in-jokes — his time in California is recalled as “the wildest of times and the best of times (with burning leaves)” and continues with the note that “Brock was a free spirit. He loved the outdoors, fishing, hunting and gardening. He was also a fabulous baker and cook.”

I don’t know what the reference to burning leaves means (though I have a guess), but Pemberton’s family and friends did, and that’s the important thing. If you’re a fan of the A’s, Tigers or even the Mets, you have plenty of memories of Tony Phillips and knew a little something about his life; only the most committed Mets fan remembers Brock Pemberton or knew anything about what he did away from baseball stadiums.

But they were both Mets, both ballplayers, both sons and brothers and husbands. And both gone before what those they left behind had hoped would be their time.

When I first became a fan, the vast majority of the men who’d been Mets were still alive — it was only 14 years since there’d been New York Mets, and the exceptions, such as Danny Frisella and Gil Hodges, were tragedies. Now, four decades later, it’s different. Nineteen of the 45 ’62 Mets are no longer with us. There will come a day when only a few are, and then one, and then none, and the other rosters will follow suit, from the ’60s into the ’70s and then the ’80s and one day the teens of a no longer so new millennium.

It’s the way of baseball because it’s the way of all things. And it will be up to us to remember these men who were Mets, from stars and can’t-miss prospects and Hall of Famers to scrubs and did-miss prospects and trivia answers. Like Tony Phillips. And like Brock Pemberton.

by Greg Prince on 19 February 2016 7:00 pm Here are two scenes from two Florida locales at the outset of Spring Training.

1) Lucas Duda is asked about the throw that got away and, with it, the World Series. He replies:

“That’s a throw I can make nine out of ten times, and that happened to be the one I didn’t […] I’ve watched it a few times. He was dead to rights. I wish I would have got him. No excuses. I threw the ball away.”

2) Jon Niese discusses pitching on the night his son was born:

“That’s when it all went downhill […] If I wouldn’t have pitched that game, I probably would have stayed the course, stayed in a rhythm, but that just kind of knocked me off.”

Duda is still a Met and quite a mensch. Niese is a Pirate with an alibi.

The play which Duda was asked about in Port St. Lucie on Thursday is already legendary from a Kansas City perspective. If there are still sports bars, photographs and frames a century from now, a framed photograph of Eric Hosmer scoring on Duda’s terrible ninth-inning throw — thus tying the score of the fifth game of the 2015 World Series — will likely hang in every sports bar in western Missouri and eastern Kansas.

It was a happy episode for Hosmer and Royals fans. It’s haunting for us and Duda. Duda said so. No practiced amnesia for him. Also, no alibis. The light didn’t get in his eyes. The noise didn’t get in his ears. The angle wasn’t troubling. Some bump in the road from several months before didn’t rise up to swallow his ability. He just didn’t make a play he could’ve/should’ve made. He owns up to it in honest, forthright fashion and has folded it into his experiential portfolio, planning to “learn from it, grow from it and kind of fuel me”.

Absorbing the Quotes of Spring from the defending National League champions, it seems the bulk of the Mets are revved up for another go at postseason fulfillment. Nobody wants to evince overconfidence (let alone cockiness), but the sense of purpose is palpable. It’s not only different from every spring thing we’re used to lately, it’s a step up from those warmup periods most historically comparable to this one.

The last pair of springs during which the Mets were technically defending a National League flag indicated the Mets didn’t want to be reminded of their recent successes. There was, as Ira Berkow noted, a lot of “putting that behind them” for the 1987 Mets, as if somebody wouldn’t want to mistakenly stumble into 108 wins two years in a row. Fourteen Februarys later, as the inimitable Lisa Olson put it, “the ‘what ifs?’ turned into ‘what nows?’” The vibe out of the East Coast of Florida in 2001 — unlike the buzz that permeates the first baseball days of 2016 — didn’t resonate with determination regarding completion of unfinished business.

Back in the present, on the other side of the Sunshine State, Niese, who now receives his springtime mail in Bradenton, recounted where his 2015 went awry. He told a Pittsburgh reporter on Wednesday that he chose the wrong night to pitch on one occasion…an enormous occasion in his and his family’s life. Nobody begrudges him his inability to multitask last July 24. Nobody with an iota of humanity begrudged him then. The birth of a child is no fleeting distraction.

Whether it derailed the remainder of his season is questionable. Only Niese, since traded for Neil Walker, knows what worked for him and what conspired to betray him. In the same interview with the Post-Gazette, he added that the occasional forays into a six-man rotation bugged him as well. He’s not alone among Met pitchers who chafed at not throwing as often as he preferred, but he is the only one pointing to it as a cause for his personally falling short in the aftermath of a team triumph.

He’s also the only one among those who were regular starters for the 2015 Mets to be on another team and therefore not answering questions about what it will be like trying to get back to the World Series.

One Met performs badly at a crucial moment, takes responsibility for it and is ready to try to win another pennant. One Met performs inconsistently in general, offers a couple of possible explanations — neither of which was as simple as “no excuses” — and we have a pretty solid second baseman to show for it.

***

We join the rest of the baseball world in mourning the sudden passing of Tony Phillips, dead of a heart attack at the ridiculously young age of 56. Phillips competed fiercely in the majors for parts of eighteen seasons, stopping off at Shea for two months in 1998 to lend a veteran hand to a playoff push that came up a game or so shy of a Wild Card. He gave the Mets one particularly memorable home run in early September and me a thrill that feels wonderful to remember to this day.

by Greg Prince on 16 February 2016 4:44 pm One of my least favorite conversational tics is somebody rebuffing me with, “Don’t get me started.” We’re having a conversation. We’ve by definition started. Don’t get you started? It’s too late, Billy Crystal. We’re already in progress.

I got started on one of the longest conversations of my life eleven years ago today, February 16, 2005, when Faith and Fear in Flushing signed on the air. We’re still talking. We’re not stopping. Why would we?

Truth be told, valued reader, you are getting only part of the conversation. It’s not as if I’ve been intentionally holding back; rather, I just don’t write everything down. The deepest oral history of the New York Mets as regards their past, present and future (but mostly their past) has gone unrecorded, for it consists of me wandering around at any given hour of the day or night talking to myself about the Mets. These sessions usually occur when I’m on the verge of doing something else, but instead of doing it, I put it off because I’m too heavily engrossed in a spontaneous Metsian monologue that would pass for a dialogue if only it wasn’t just me going back and forth. This spoken stream of consciousness usually spans a multitude of things that happened many years before, though occasionally a handful of things that are due to happen scant hours from now, whenever now happens to be.

The subtopics are varied, but the umbrella subject is inevitably the Mets. Even when it begins about something else, it transitions into the Mets. The Mets are what I’d rather think about, so the Mets are what I tend to wind up talking about, even if it’s only the furniture, the cats and my inadvertently present ears that end up hearing it. For all I know, these talks might be vastly entertaining. They might be better than TED Talks and at least as good as Teddy Martinez talks. I’m too much in the middle of them to objectively assess.

I’ve been co-authoring a blog for eleven years, yet I still talk to myself much of the time about the Mets. If I didn’t have this outlet, I suppose I’d be doing it all of the time. So thank you for making my behavior on the whole at least marginally socially acceptable.

It’s no coincidence that our twelfth year of conversation commences with the onset of another preseason. The pause button that was tapped no more than lightly in winter gets its definitive push ahead. Press play. Follow the favorite mantra of Texas Ranger minor league invitee Ike Davis.

Start us up. If you start us up, we’ll never stop.

We love a sport in which the clock plays a marginal role, yet we love to count down. We count down to Pitchers & Catchers (increasingly a misnomer, since a majority of Mets, regardless of position, flock to Port St. Lucie ahead of instinctively ballyhooed reporting date). We count down to the first exhibition game, a.k.a. game that doesn’t count. We count down to the first real game. We count down Magic Numbers when we’re lucky enough to be dealt a stack. Baseball may be timeless, but ain’t it funny how time keeps slippin’, slippin’ into the future?

Predictions and projections dot the landscape. How are the Mets gonna do? How many are they gonna win? How many are they gonna win by? How many will they have to win in order to have a shot at winning more than they won the year before, when they almost won it all? Much as we pretend what happens in Spring Training counts for a ton, we pretend to have a handle on what will happen when the games really do matter.

And we don’t know. We just don’t. Sometimes that’s frightening. Sometimes it turns out to be exhilarating. All of the time it keeps us engaged, whether it’s in the welcome company of others who share our preoccupation and conversation or quietly to ourselves when nobody’s listening, except for ourselves.

by Greg Prince on 13 February 2016 12:18 pm A PED test must be as imposing to Jenrry Mejia as the geometry Regents was to me. I struggled with geometry throughout ninth grade and barely passed the big statewide test the one and only time I had to take it. I’m not sure how many times Jenrry had to take his PED test. We do know he failed it three times in a span of approximately ten months.

They probably wouldn’t have let me graduate had I been as certifiably bad at geometry exams as Mejia is with PED tests. As is, they won’t let Jenrry matriculate in the major leagues anymore.

Avoiding PEDs is clearly not this young man’s best subject. Nor, we are compelled to infer, is judgment.

Jenrry could pitch better than most people. He pitched well enough to be signed by the New York Mets to a professional baseball contract when he was 17. When I was 17, I was barely getting by in an eleventh-grade statistics class. When Jenrry wasn’t much older than 17, he was compiling statistics as a Met. Mejia debuted at the age of 20, which sounded so old when I was in high school, yet sounds so young when you’re so much older. He impressed everybody in his first big league camp. He made the Mets far ahead of anybody’s projections. Barely three years after the Mets signed him, he was pitching for them. In his first outing, he gave up a run in an inning. In his next thirteen outings, he gave up one run in twelve-and-a-third innings.

Jenrry Mejia was a quick learner at 20. Somewhere between the ages of 25 and 26, that core competency eluded him.

Can you believe that someone who is 26 years old — younger than Matt Harvey, younger than Jacob deGrom, younger than Travis d’Arnaud and a whole lot younger than Pete Rose c. 1989, the year Mejia was born— has been issued a Roselike lifetime ban from Major League Baseball? That’s a lot of lifetime to be banned from anything, let alone the institution in which you ply your craft, the particular endeavor in this world at which you had already proven yourself uniquely talented and for which you were compensated handsomely. Twenty-six was literally more than half a lifetime ago for me. I’d hate to have been told at 26 that I was no longer invited to participate in my version of striking out hitters (not that I necessarily possessed an obvious ability or track record comparable to Jenrry’s by that age…or my current age).

I’d really hate to have been put in such a position because I did the one thing I wasn’t supposed to do, and did it three times.

I’m not concerned with what Jenrry Mejia’s ejection from MLB-sanctioned activity means to the Mets. Whereas he was once the focal point of their relief pitching, Mejia was going to enter 2016 as a literal afterthought. He had 99 games of suspension left to serve from the second time he failed a PED test. After 99 games, depending on where the Mets’ bullpen stood, maybe I was going to think about him. Maybe. Although relievers are constantly being penciled into plans and just as vigorously erased from them, I couldn’t drill down deeply enough to a level where I wondered, “…and what will we do with Jenrry Mejia come the 100th game of this upcoming season?”

No need to engage in that afterthought now. Jenrry Mejia will not be available in the hundredth game of 2016 nor any game any year soon. There is a reinstatement process he can look into, but not for quite a while. By then, even if he succeeded in gaining re-entrance to the majors, more of his and his old team’s lifetime will have transpired. There’s no telling what kind of shape a tangibly older, generally inactive, presumably clean Mejia would be in. One can guess with fair certainty the scant interest level of the team under whose umbrella he failed those three tests within ten months. I was surprised the Mets offered him a contract for 2016. I’d be shocked if we ever again see him pitching within the geometry that composes a major league diamond, Citi Field’s or anywhere else’s.

Then again, I was shocked at the third failed test, and that happened.

Because it’s not notably screwing with the Mets’ impending defense of their National League title (and therefore my second-hand happiness), I’m not going to gin up any anger toward a pitcher I always liked. Even if it was notably screwing with the Mets’ impending defense of their National League title — even if he was theoretically slated to close 162 games this year — I doubt I could get honestly mad at Mejia. He’s just not the kind of kid on whom I feel comfortable piling easy epithets. He made three mistakes Tim McCarver might have labeled errors of commission rather than omission. What he had to do was omit PEDs from anything he chose to ingest or inject. As gauged from the distance of the grandstand and the keyboard, his mistakes appear to have been perfectly avoidable and thus strike us as progressively more absurd.

You get caught once, don’t do the thing they caught you at again. You get caught twice, really don’t do the thing they caught you at again. You get caught a third time, which is the point at which suspension becomes expulsion, well, Jenrry, you don’t need anybody to call you names.

You need help. Good luck finding it.

by Greg Prince on 8 February 2016 1:28 am For about five minutes late Sunday night I identified with the plight of the Carolina Panthers fan, remembering what it was like to climb to within a few feet of the top of the mountain only to slide irrevocably downhill. Now that the 50th Super Bowl is a rapidly fading gold-plated memory, I’m no longer feeling any kind of Met-Panther brotherhood in the realm of so close/so far. Instead, I’m anxious to peer toward the other sideline and for the Mets to go do in baseball what the Denver Broncos just did in football.

Here in New York, where we haven’t had a major league champion of any kind in now more than four years, the Empire State Building was lit up in orange and blue to reflect Bronco glory. Nice color scheme. I’ll take it as practice for how it should glow within nine months.

You can never start preparing too soon. The final gun on football annually signals to we who congregate in the Church of Baseball the run-up to Spring Training. That’s probably a little presumptuous and short-sighted as rehearsed reactions go. There’s still snow on the ground (and more to come ASAP) and, besides, who cares when football begins or ends? Baseball is always going on in the head, heart and soul. Soon, activity related to it will take place in Port St. Lucie.

Pitchers & Catchers represents one small step for Mets. Opening Night in irony-riddled Kansas City is what will bring about the giant leap for Metkind. But it is said you’ve gotta walk before you can run, and we went to the trouble of trading for a literal Walker, thus it must be true. So yeah, let’s rustle up some pitchers, some catchers, a De Aza, a Cabrera, a Bastardo and the rest of the cast, familiar and otherwise.

Metropolitan Team Baseball Force assemble! Even if it’s only initially for stretching and soft-tossing.

Carolina won’t be in my mind much longer, but since it’s still slightly lingering, I sort of wonder how Panther people will look back on their 2015. They had a very good year, but on the biggest stage, they stumbled. Does anybody raise a Conference Championship flag in football? A pity if they don’t. Enjoy the part about getting there all you can. Try to compartmentalize the part that didn’t go right, even if it was the biggest part of all.

We on the wrong side of the baseball finals still have our pennant to raise, of course, and we still have “the World Series” in our psychological portfolio. Why the quote marks? Because it occurred to me in the weeks and months that followed the last set of games the 2015 Mets played how much I enjoyed the way “the World Series” kept rolling off my tongue. Even when I wasn’t specifically engaged in baseball chatter, I found “the World Series” became a marker of time. Things happened “during the World Series”; other things happened “right after the World Series”. I wasn’t forcing it into conversation — it was just the prism through which I viewed my autumn.

I liked the view (the way we made it there, not what happened to curtail our stay). But now it’s receding. I simply don’t find as many naturally occurring reasons to invoke “the World Series” in February as I did even in January. Makes sense. That World Series ended just over 14 weeks ago. Uncharacteristically, it doesn’t make me sad to realize how vast the chasm between what is “now” and what will always be then will eventually become. Despite my reflexive simpatico for whoever was going to not win the Super Bowl — the first professional sports championship to be not won since the Mets neglected to win theirs — I’m not looking back wistfully. I’m looking ahead excitedly. I mean legitimately, not just for the crack of the generic bat and the perennial platitudes regarding the Florida sun.

We had a World Series team. We are positioned to have another one. There’s much to be done to return to that elevated state of existence, where “the World Series” is a place we call our own and a time we know to be ours, but it’s February, we have Cespedes and Harvey and deGrom and Syndergaard and enough reasons to believe in advance. The snow is old hat in late winter, but the tangible optimism this late winter is as fresh as new-fallen hope.

Just under eight weeks to Opening Night. Now that will be a Super Sunday.

The official publication date for Amazin’ Again, the definitive story of the 2015 Mets, written by yours truly, with a foreword by none other than the great Howie Rose has been set for March 15. Pre-order your copy here so you don’t have to wait one day longer to relive the greatest 21st-century season our favorite team has ever known.

And listen to me expressing organically occurring enthusiasm for the 2016 Mets here on the Rising Apple Report.

by Greg Prince on 26 January 2016 1:49 am On October 2, 2005, Mike Piazza entered the home clubhouse at Shea Stadium, removed No. 31 from his person and left the building. No. 31 didn’t go anywhere.

But now it will.

No. 31 heads for the esplanade above the left field wall at Citi Field, right where it’s belonged (give or take some architectural adjustments) since there was a left field wall at Citi Field. Mike Piazza announced his retirement in 2008. Citi Field opened in 2009. Ceremoniously revealing No. 31 out there amid the handful of other officially decirculated numerals would have been a fine way to welcome the New York Mets and their fans to their new home. It also would have represented walking while chewing gum to a franchise brain trust that was preoccupied with reminding us that another team once played ball in an adjacent borough.

So No. 31 waited quietly to make its big appearance. It waited seven Citi Field seasons. It won’t have to wait out an eighth.

On Monday, the Mets announced Mike Piazza’s No. 31 has been granted the same exalted status extended Casey Stengel’s No. 37, Gil Hodges’s No. 14 and Tom Seaver’s No. 41. For the first time in 28 years, the Mets will retire the uniform number of a Met.

Ain’t that Thirty-Onederful news?

It never seemed unlikely, but with the Mets, you couldn’t tell. Mike Piazza was their main man for eight seasons, almost all of which were spectacular for the player, two of which were stupendous for the team. He was singularly to 1999 and 2000 what Seaver was to 1969 and 1973. He was as good as there was in his era in a Mets uniform, a uniform in which the Mets won, in great part, because of him. In many places, that gets your number retired. Here it got your number set aside. We figured the day would come when it would get its proper due.

The day will be Saturday, July 30. The Mets will dedicate an entire weekend to Mike Piazza one week after the sluggingest catcher ever is inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The timing doesn’t seem coincidental. The Mets took their honoring cue from Cooperstown, as if No. 31 couldn’t be hallowed in the Mets’ midst until somebody else vouched for its transcendence.

Seemed an unnecessarily drawn-out formality (just like Mike’s election to the Hall), but if that’s what it took, then consider No. 31’s passport to the uppermost echelon of Met magnificence stamped. It doesn’t get any more elevated than the space above the left field wall. That’s where your number goes when there are no words left to say.

Mike Piazza’s Met deeds often left us speechless. No. 31 will now and forever speak volumes.

by Greg Prince on 23 January 2016 11:57 am Moving in alongside the storm front that had just begun enshrouding the New York Metropolitan Area Friday night was much better breaking news: the Mets were opting in, all in, to the 2016 championship chase, re-signing Yoenis Cespedes to a three-year deal that may function as only a one-year deal but is clearly superior to the no-year deal that seemed set in stone throughout this previously discontented winter.

With Cespedes’s decision came climate change we could all embrace. The weather outside is frightful, but looking forward to this particular baseball season just became incredibly delightful.

Yoenis was offered a longer, more lucrative deal to defect to our de facto archrivals. He turned it down. You didn’t need an interpreter to understand what La Potencia’s actions had strongly implied:

“You couldn’t pay me enough to play for the Washington Nationals.”

What made the agreement that will have the Mets paying Cespedes a pretty fair wage so intoxicating for the likes of us — people conditioned to crave a contact high from another individual’s $75 million jackpot — was our team offered him significantly less than he could have received elsewhere to remain a Met and he said, in essence, no problema.

After anxiously waiting out the transactional equivalent of a scoreless 237-inning affair (we weren’t checking Twitter every three seconds just for snow forecasts), the Mets finally pushed the winning run across. When given every opportunity to bring back a superb player who had played superbly for them and wished to continue playing for them because he specifically liked playing for them, they brought him back. They didn’t get in their own way and they got it done. It enhances their chances for 2016 and reassures us that ownership may in fact be capable of operating a large-market franchise in the foreseeable future.

Up until this point, recent pennant and formidable pitching notwithstanding, there was doubt pervading the prevailing Met mood. Now there is confidence. As World Series Game Four national anthem singer Demi Lovato’s been asking regularly on the radio, what’s wrong with being…what’s wrong with being…what’s wrong with being confident?

We have a team poised to not just contend but perhaps to repeat. This isn’t the addition of a star player to an enterprise that hasn’t won anything in its current era, where you’re sort of crossing your fingers that throwing money at your shortcomings will magically change your fortunes. This is a defending league champion heading toward its next year with no obvious holes because it just sealed its last potentially gaping void. Why shouldn’t we be confident?

It feels good to feel good about the Mets. We felt good about the Mets a whole lot in August and September and the vast majority of October. Then, as the World Series faded into inevitable memory and little indicated reaching another one topped the organization’s agenda, we drifted back toward being 21st-century Mets fans, for whom nothing feels very good for very long.

The offseason had been uninspiring. Neil Walker. Asdrubal Cabrera. Alejandro De Aza. Lately Antonio Bastardo. Nice players, to use the blanket phrase with which one covers sensible acquisitions, but nice is kind of a comedown when everything felt so good not so long ago.

2015 was more than good. It was truly Amazin’ (and the kind of season you’ll want to read about Again and Again, hint hint). When you’ve been party to something that good, you don’t want to slide back to anything less any time soon.

2016 was definitely too soon.

The tenor of November and December and January had been increasingly downcast. It wasn’t about the players we got. It wasn’t even about the players we didn’t get. It was about the players we weren’t going after. And maybe the players who were going away…and where they were going.

Daniel Murphy was going away. We could handle that. He was going to the Washington Nationals, our de facto archrivals. Coping with that development was as precarious a matter as Daniel’s pursuit of any given ground ball. Depending on your #with28 predilections, it was either just business or a slap in the karmic face. Even if you framed Murph as a net negative and projected him to become a Nat negative, it was tacky. The guy who won the only sanctioned MVP award earned by any Met since Mike Hampton wasn’t going to be tucked away in a Denver suburb reviewing his kids’ homework, mostly out of sight, out of mind. He set himself up to be a 19-game-a-year reminder of what was and what might not be again.

We didn’t need another one.

If Cespedes had taken his bat, his flair, his parakeet, his stylish rendition of green sleeves and our memories of what he did for us in 2015 to some distant precinct in search of the biggest pile of cash available — as professional athletes are wont to do — that would have been just business. If Cespedes had accepted the tempting offer reportedly on the table from the Nationals, that would have been a kick in the head to go along with the aforementioned slap in the face. Murphtober was history and the Summer of Cespedes was on the verge of joining it there. It was a slippery slope to a surfeit of 2-1 losses and Danny Muno batting third.

But Yoenis didn’t go in that direction. He could have collected $100 million or so from the Nats over five years, give or take some deferred compensation, and instantly converted his Citi Field currency from cheers to boos. Or he could he could reach accord with the perennially resource-challenged Mets, who dangled three years for $75 million, with $27.5 million in the first year and an opt-out clause at his market-testing discretion immediately thereafter.

He went with the Mets. Word was he was enormously enamored of being a Met, but who believes words like those in this Money Talks, Everybody Walks world of ours? Sure, Wilmer Flores wept at the thought of a trade outta Flushing and Zack Wheeler dialed Sandy Alderson to request a reprieve of his own, but their contractual status rendered them pawns in the general manager’s trade-deadline chess game. Welling up and reaching out was all they could do. Cespedes had agency. He had free agency. Even if the landscape didn’t develop quite to his benefit, he could have found an impressive stack of bills somewhere. One was ready for him in Washington, where he seemed destined to alight, teaming with Daniel Murphy and Bryce Harper and making us disdain the Nats almost as much as we would have snarled at our uppermost management.

“It is money they have and peace they lack,” Terrence Mann said of prospective pilgrims converging on a converted Iowa farm in Field Of Dreams. Cespedes was going to have plenty of money regardless. He found peace (or perhaps stimulation) in a New York Mets uniform and decided it fit him perfectly. We dream of players doing that. Flores tugged at the insignia on his at the end of the night that followed the day Cespedes first became a Met; it served as Wilmer’s requitement of our affection. Yoenis signing his name more formally on a bottom line, no matter how literally valuable the act is for him, sends a similarly priceless message to Mets fans.

He likes us. He really likes us.

We needed to hear that. We needed the Mets to allow us to hear that. We needed to know that what we experienced last year wasn’t a whirlwind affair, that flirting with a commitment to winning ran deeper than a late-summer fling. We know Cespedes may never again be the force of nature he was for those seven platinum weeks in August and September — thus the reasoned reluctance to enrich him well into the next decade — but we also know he’s capable of creating a blizzard of offense and was our best bet to precipitate all over opposing pitchers in 2016. The extant on-site alternatives were nice players. They still are. I like Juan Lagares. I have nothing against Alejandro De Aza. But they’re not Yoenis Cespedes.

Few are. We’ve somehow maintained the presence of the only one who is. It feels very good indeed.

by Jason Fry on 20 January 2016 7:26 pm I’ve spent a good chunk of the winter sulking about Jeurys Familia quick-pitching or Yoenis Cespedes playing base-soccer or Daniel Murphy bringing the glove up or Cespedes charging off first on a soft liner or Terry Collins being too sentimental or Lucas Duda being unable to make a simple throw home or getting to the big stage only to be cast as the Washington Generals.

And perhaps one day I’ll write about that beyond a single run-on sentence followed by a big sigh.

But I’ve done something else this winter, probably by way of therapy: I’ve charged through the rest of my work to make The Holy Books even more holy.

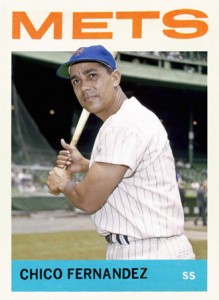

Years ago I dived into Photoshop to make cards for the nine Lost Mets who’d been denied so much as an odds-n-sods bit of cardboard from some fringe set. I should have known that was only the beginning. I should have guessed that the presence of non-Met cards in The Holy Books would start to bug me and keep bugging me. I should have intuited that it would bother me to have less than a full set of Mets managers with their own cards. I should have divined that once I started putting aside cards of Met ghosts I’d want those almost-Amazin’s to have cards in orange and blue as well.

It took me a while — denial is a powerful thing — but eventually I decided this was something I had to do. I would correct the historical record by making sure every Met before the dawn of respectable minor-league cards — that’s 1980 by my reckoning — got a Topps-style Mets card showing that player in Mets garb.

That meant not just the Lost Mets, but also any Mets around too briefly to get Met cards — the Frank Larys (Laries?) and Ron Herbels and Doc Mediches of the world. Cup-of-coffee guys who had to share space with one or three other young hopefuls on Topps rookie cards — Bob Moorhead and Billy Murphy and Benny Ayala and friends. Guys whose moment in the cardboard sun came years later in specialty sets — Willard Hunter, Joe Moock, Billy Baldwin and their fraternity. Players stuck with black-and-white Tides cards — Jay Kleven and Randy Sterling and others like them.

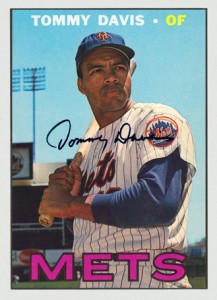

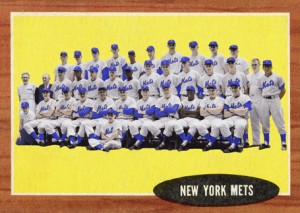

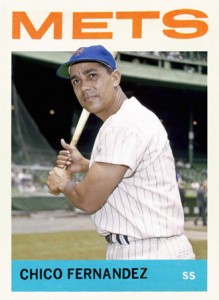

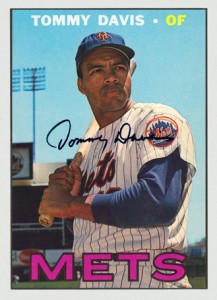

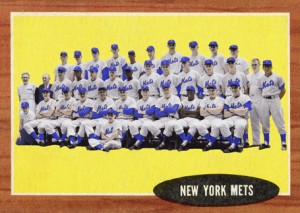

I decided it also included guys whose lone Mets cards featured doctored images of them with other teams — your Larry Burrights and Tommy Davises and Bob Gallaghers. That principle led me, reluctantly at first, to conclude that the ’62 Mets not named Ed Bouchee or Al Jackson deserved cards in which they were really Mets instead of hastily concealed Braves and Reds and Cubs. Oh, and those inaugural Mets needed a team card of their own.

The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards? The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards?

That left me a first volume of The Holy Books that would be all Mets and Tides, with four exceptions: Dave Roberts, Dick Tidrow, Larry Bowa and Tim Corcoran. By now I don’t need to tell you what I decided about them.

It added up to 158 cards — and an amount of time and money that would have made me scrap the whole project if I’d understood what I was getting into. I bought unused Topps photos and autographed images (which, ironically, I then de-autographed using Photoshop) and scoured yearbooks and baseball-photography sites. Sometimes I transformed photos of guys in other uniforms into Mets, which taught me that an Atlanta away uniform is easily converted into a Mets road jersey, while a Yankees or Phillies home jersey is your best starting point for creating New York (N.L.) pinstripes.

So much for the fronts. But what about the backs? This was the part I feared would be drudgery … but actually turned out to be fun. A player’s statistics told a tale — usually one that took a sad or frustrating turn, since by definition we’re talking about the last guys on rosters. And each player had an actual story, one I had to delve into to create my cardbacks’ diplomatically phrased bios and career-highlight cartoons. (I’m proud to say I never had to resort to something safely generic, such as opining that Jim Bethke enjoys music.)

Learning those stories transformed random guys from long-ago rosters into people whose recollections could have filled a barroom for hours. Every Met turned out to be interesting, having been party to a tragic turn of events, a missed opportunity or — sometimes — a decision that other things were more important. And those stories gave me a window into an era of baseball that now seems impossibly distant.

There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League. There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League.

’62 Mets hurler Ray Daviault spoke nothing but French before he left his native Montreal for an odyssey that took him to Cocoa, Fla. (Florida State League); Hornell, N.Y. (Pony League); Asheville, N.C. (Tri-State League); Pueblo, Colo. (Western League); Macon, Ga. (South Atlantic League); Montreal (International League — and home!); Des Moines, Iowa (Western League again); back to Montreal; back to Macon; Harlingen, Texas (Texas League); Tacoma, Wash. (Pacific Coast League); Syracuse, N.Y. (International League again); and finally the Polo Grounds.

Another ’62 Met, Sammy Drake, split 1956 between Ponca City, Okla., in the Sooner State League and Lafayette, La., in the wonderfully named Evangeline League, also called the Tabasco Circuit. 1956 was an odd year even by Evangeline League standards: the New Iberia Indians disbanded in May, leaving seven teams on the circuit. Drake’s Lafayette Oilers beat Lake Charles in the first round of the playoffs and were set to play Thibodeaux, but the finals were cancelled because of a lack of interest. The Oilers’ default co-champion status didn’t help them in 1957; they disbanded in June, at which point Drake was in the Army.

While in the Evangeline League, Drake probably heard of the legendary Roy Dale “Tex” Sanner, who’d won the circuit’s batting triple crown for Houma in 1948, hitting .386 with 34 home runs and 126 RBIs. The amazing thing was Sanner had also gone 21-2 as a pitcher with 251 strikeouts and a 2.58 ERA that year, missing the pitching triple crown by one win, eight Ks and a fifth of an earned run — a distinction he lost out on because he jumped ship to finish the year with Dallas. Sanner sounded like some Paul Bunyan of bayou baseball, but he was real — ’62 Met Willard Hunter played with Tex at Victoria in 1957, when both were Dodger farmhands. Hunter was 5-6 in 15 games; Sanner went 12-4 for the year and hit .331. Victoria won the ’57 Big State League title, after which the loop ceased to exist.

Today semi-pro leagues are an oddity, but back then they were an essential part of many players’ rise. Sixteen eventual Mets — including Moock, Shaun Fitzmaurice, Al Schmelz, Dennis Musgraves, Gary Gentry, John Stearns and Bob Apodaca — honed their skills in South Dakota’s Basin League, an amateur summer circuit which began in 1953 and lasted until the early 80s. (Jim Palmer, Bob Gibson and Frank Howard were Basin League vets.)

For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3. For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3.

Another independent circuit, the Mandak League, thrived in the 1950s as a haven for former Negro League players and African-American and Latin players who’d been driven out of pro ball or refused to put up with the abuse required to stay in it. Before he turned pro, Sammy Drake had a tryout with the faded yet fabled Kansas City Monarchs and got his start in the Mandak League as a Carman Cardinal, a move he made in part on advice from older brother Solly, who told him the largely Canadian league was an easier place to play than the South. After signing with the Cubs, Sammy Drake joined Ernest Johnson as the first black players for the Macon Peaches, and learned all too well what Solly had warned him about.

Race kept some players from the big leagues or delayed their arrival — ask Ed Charles or Al Jackson about that — but players also had to deal with farm systems that were ill-suited for developing young talent. Baseball didn’t dismantle its bonus-baby rules until ’65, and countless careers were short-circuited by bringing players up too early and then leaving the shell-shocked rookies to rot on the bench or in the bullpen. As if that wasn’t enough, players could be undone by internal politics, skullduggery designed to thwart other organizations, or simple incompetence.

Before I started my insane project, Jerry Hinsley was half of a Met rookie card, the less-than-proud owner of a 7.08 ERA in 11 career games. But Hinsley went 35-0 as a high-schooler in Las Cruces, N.M., helping his team to three straight state championships and throwing three no-hitters along the way. The Pirates signed him (with twin brother Larry for company) for 1963, but wanted to keep him from being taken in the first-year draft. So they sent the 18-year-old to Kingsport, Tenn., and told him to pretend he had a sore shoulder. Hinsley didn’t pitch a single inning all year.

Mets scout Red Murff knew about Hinsley and wasn’t fooled. The Mets drafted the young pitcher and found a new way to abuse him — they had him make his pro debut in the big leagues. Hinsley racked up an 8.22 ERA before he was sent down at the end of May, made it back to the majors for a ’67 cup of coffee and retired at the end of ’71 — still just 26 — as an Indians farmhand. If he’d been treated differently, who knows what might have been?

Misfortune destroyed other careers. Dennis Musgraves threw two no-hitters in college and signed a then-record $100,000 bonus with the Mets in ’64. Rushed to the big leagues in July ’65, he followed three strong relief appearances with a seven-inning start against the Cubs in which he allowed just one earned run. The next morning his elbow was swollen and his pitches couldn’t reach the catcher. He’d endure two elbow operations and remake himself as a junkballer, but never returned to the big leagues — his 0.56 ERA will forever be a what-if. Ditto for Dick Rusteck, whose big-league debut was a four-hit shutout against the Reds in June ’66 — followed by a hurt shoulder and a bad elbow. Unfortunately for the likes of Musgraves and Rusteck, Frank Jobe was nearly a decade away from trying a novel surgical procedure on the left elbow of Tommy John, and most sore arms were professional death sentences.

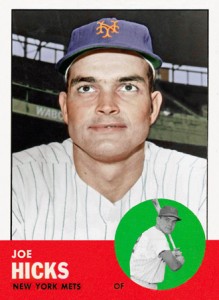

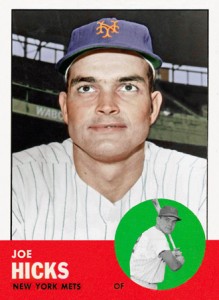

Joe Hicks, who hit .226 for the ’63 Mets, never had one big thing go wrong for him — just a succession of small and medium-sized things. Hicks was signed by the White Sox out of the University of Virginia in 1953 and hit .389 for Madisonville in the Kitty League, finishing the year with a .346 average for Colorado Springs. He hit .349 the next year, then .299 for Memphis in ’55. He was 22 years old, one step from the majors, and Chicago needed outfielders.

Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape. Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape.

Then there were guys whose highlights came before their debuts — sometimes on bigger stages than you might guess. Ted Schreiber was born in Brooklyn, grew up a Dodgers fan and went to St. John’s. In 1958, with the Dodgers gone, Ebbets Field was home for a handful of Long Island University and St. John’s games. On April 24, Schreiber hit a game-winning two-run homer there. Five years later, he’d play at the Polo Grounds as a Met.

Or take Shaun Fitzmaurice, who’d have given Michael Conforto a run for his money in the hype department if we’d had Twitter in 1966. Fitzmaurice had power and speed that made scouts compare him with Mickey Mantle. While a Notre Dame student in 1963, Fitzmaurice slammed a 500-foot home run against Illinois Wesleyan that’s lived on in college lore. USC coach Rod Dedeaux — who’d help shape Seaver’s career — took Fitzmaurice as an Olympian for the 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo, and he hit the game’s first pitch for a homer.

Fitzmaurice never hit a Met home run, but this one almost counts: In 1961 he played for the U.S. All Stars in the Hearst Sandlot Classic at Yankee Stadium. With two out in the ninth, Fitzmaurice drove a ball 400 feet, tearing around the bases for a two-run inside-the-park home run. The teammate he drove in? U.S. All Stars’ second baseman Jerry Grote, whose double-play partner for the game was Davey Johnson.

One story left me happy about what was instead of wondering what could have been. It’s the tale of Bill Graham, briefly a Tiger and Met. All I knew about Graham was that he shared a name with the rock promoter and always looked like his hat didn’t fit. But there was a lot more to him than that.

The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case. The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.

Graham, the son of a Flemingsburg, Ky., physician, had stepped away from baseball to become a doctor. He completed his degree at Elon College in North Carolina in 1962, then went to medical school at UNC and the University of Kentucky. He came back to baseball at 28, won 12 games for Syracuse in ’65 and helped Mayaguez to a winter-ball title. He was older, wiser and far from the typical prospect.

“I’m at an age now that another year in baseball won’t make any difference, except to steer me either way,” he told a reporter during 1966 spring training. “The hardest thing is to get into medical school, and I worked too hard not to take the opportunity. I like baseball and I’ll see what happens this year.”

What happened was that Graham pitched well in a second go-round with Syracuse and made his big-league debut in Detroit’s final game of 1966. Next August, after a 12-6 season with Toledo, he was purchased by the Mets. Graham made three starts for the Mets; on September 29 he scattered six hits in a complete-game victory against the Dodgers.

It was Graham’s first big-league win. It was also his last professional appearance.

What happened? William A. Graham Sr. was ill, so his son went home to Flemingsburg to care for him. The younger Bill Graham missed the ’69 World Series and the chance to build on an intriguing story.

Or rather, he missed the chance to build on that story.

Graham did well back home in Kentucky. He farmed, developed land and became a mainstay of local government and business, serving on any number of boards and commissions. When he died in 2006, he left Elon a $1 million bequest.

“You spend your life gripping a baseball,” Jim Bouton famously said, “and it turns out that it was the other way around all along.” Not for Bill Graham, though. He approached baseball differently, coming and going on his own terms, and it worked out pretty well.

|

|

The missing managers —

The missing managers —  There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the

There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the  For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of

For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of  Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape.

Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape. The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.

The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.