The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

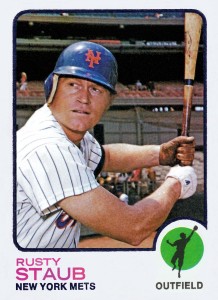

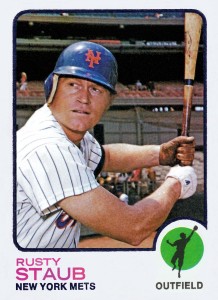

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 20 January 2016 7:26 pm I’ve spent a good chunk of the winter sulking about Jeurys Familia quick-pitching or Yoenis Cespedes playing base-soccer or Daniel Murphy bringing the glove up or Cespedes charging off first on a soft liner or Terry Collins being too sentimental or Lucas Duda being unable to make a simple throw home or getting to the big stage only to be cast as the Washington Generals.

And perhaps one day I’ll write about that beyond a single run-on sentence followed by a big sigh.

But I’ve done something else this winter, probably by way of therapy: I’ve charged through the rest of my work to make The Holy Books even more holy.

Years ago I dived into Photoshop to make cards for the nine Lost Mets who’d been denied so much as an odds-n-sods bit of cardboard from some fringe set. I should have known that was only the beginning. I should have guessed that the presence of non-Met cards in The Holy Books would start to bug me and keep bugging me. I should have intuited that it would bother me to have less than a full set of Mets managers with their own cards. I should have divined that once I started putting aside cards of Met ghosts I’d want those almost-Amazin’s to have cards in orange and blue as well.

It took me a while — denial is a powerful thing — but eventually I decided this was something I had to do. I would correct the historical record by making sure every Met before the dawn of respectable minor-league cards — that’s 1980 by my reckoning — got a Topps-style Mets card showing that player in Mets garb.

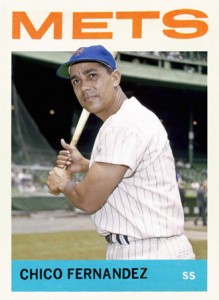

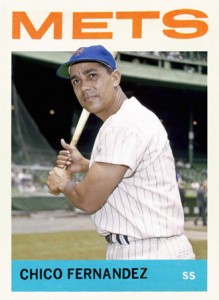

That meant not just the Lost Mets, but also any Mets around too briefly to get Met cards — the Frank Larys (Laries?) and Ron Herbels and Doc Mediches of the world. Cup-of-coffee guys who had to share space with one or three other young hopefuls on Topps rookie cards — Bob Moorhead and Billy Murphy and Benny Ayala and friends. Guys whose moment in the cardboard sun came years later in specialty sets — Willard Hunter, Joe Moock, Billy Baldwin and their fraternity. Players stuck with black-and-white Tides cards — Jay Kleven and Randy Sterling and others like them.

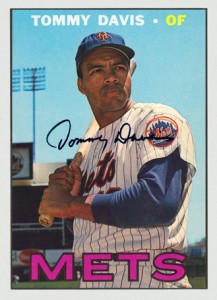

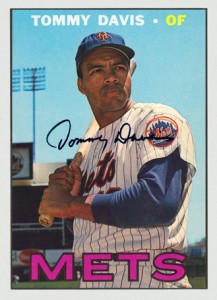

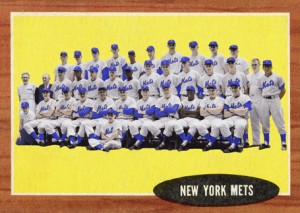

I decided it also included guys whose lone Mets cards featured doctored images of them with other teams — your Larry Burrights and Tommy Davises and Bob Gallaghers. That principle led me, reluctantly at first, to conclude that the ’62 Mets not named Ed Bouchee or Al Jackson deserved cards in which they were really Mets instead of hastily concealed Braves and Reds and Cubs. Oh, and those inaugural Mets needed a team card of their own.

The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards? The missing managers — Joe Frazier, Salty Parker and Roy McMillan — needed their own solo cards. So did the ghosts, a list beginning with Jim Bibby and ending (in this time period) with Jerry Moses. Rusty Staub would get the missing Met cards he deserved, as well as a ’72 Expos card because that was what Topps would have made if Rusty had been under contract. Now I was making non-Mets. Speaking of which, the Mets’ expansion draft picks all needed ’61 cards of their own, didn’t they? More non-Mets! How about a few prospects from Mets lore — Paul Blair and Hank McGraw and the unjustly infamous Steve Chilcott — because if you’ve gone this far, what’s three more cards?

That left me a first volume of The Holy Books that would be all Mets and Tides, with four exceptions: Dave Roberts, Dick Tidrow, Larry Bowa and Tim Corcoran. By now I don’t need to tell you what I decided about them.

It added up to 158 cards — and an amount of time and money that would have made me scrap the whole project if I’d understood what I was getting into. I bought unused Topps photos and autographed images (which, ironically, I then de-autographed using Photoshop) and scoured yearbooks and baseball-photography sites. Sometimes I transformed photos of guys in other uniforms into Mets, which taught me that an Atlanta away uniform is easily converted into a Mets road jersey, while a Yankees or Phillies home jersey is your best starting point for creating New York (N.L.) pinstripes.

So much for the fronts. But what about the backs? This was the part I feared would be drudgery … but actually turned out to be fun. A player’s statistics told a tale — usually one that took a sad or frustrating turn, since by definition we’re talking about the last guys on rosters. And each player had an actual story, one I had to delve into to create my cardbacks’ diplomatically phrased bios and career-highlight cartoons. (I’m proud to say I never had to resort to something safely generic, such as opining that Jim Bethke enjoys music.)

Learning those stories transformed random guys from long-ago rosters into people whose recollections could have filled a barroom for hours. Every Met turned out to be interesting, having been party to a tragic turn of events, a missed opportunity or — sometimes — a decision that other things were more important. And those stories gave me a window into an era of baseball that now seems impossibly distant.

There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League. There are still a ton of minor leagues, and fringe big-leaguers still lead Johnny Cash lives hopping from state to state and sometimes country to country. But it’s nothing like it was then, when the back of a baseball card was a travelogue through leagues big and small, financially healthy and decidedly not, affiliated with a big-league team and independent. Back then, players bounced from the likes of the Sooner State League to the Arizona-Mexico League to the Pony League before finding their way to a more-established loop such as the American Association, International League or the Pacific Coast League.

’62 Mets hurler Ray Daviault spoke nothing but French before he left his native Montreal for an odyssey that took him to Cocoa, Fla. (Florida State League); Hornell, N.Y. (Pony League); Asheville, N.C. (Tri-State League); Pueblo, Colo. (Western League); Macon, Ga. (South Atlantic League); Montreal (International League — and home!); Des Moines, Iowa (Western League again); back to Montreal; back to Macon; Harlingen, Texas (Texas League); Tacoma, Wash. (Pacific Coast League); Syracuse, N.Y. (International League again); and finally the Polo Grounds.

Another ’62 Met, Sammy Drake, split 1956 between Ponca City, Okla., in the Sooner State League and Lafayette, La., in the wonderfully named Evangeline League, also called the Tabasco Circuit. 1956 was an odd year even by Evangeline League standards: the New Iberia Indians disbanded in May, leaving seven teams on the circuit. Drake’s Lafayette Oilers beat Lake Charles in the first round of the playoffs and were set to play Thibodeaux, but the finals were cancelled because of a lack of interest. The Oilers’ default co-champion status didn’t help them in 1957; they disbanded in June, at which point Drake was in the Army.

While in the Evangeline League, Drake probably heard of the legendary Roy Dale “Tex” Sanner, who’d won the circuit’s batting triple crown for Houma in 1948, hitting .386 with 34 home runs and 126 RBIs. The amazing thing was Sanner had also gone 21-2 as a pitcher with 251 strikeouts and a 2.58 ERA that year, missing the pitching triple crown by one win, eight Ks and a fifth of an earned run — a distinction he lost out on because he jumped ship to finish the year with Dallas. Sanner sounded like some Paul Bunyan of bayou baseball, but he was real — ’62 Met Willard Hunter played with Tex at Victoria in 1957, when both were Dodger farmhands. Hunter was 5-6 in 15 games; Sanner went 12-4 for the year and hit .331. Victoria won the ’57 Big State League title, after which the loop ceased to exist.

Today semi-pro leagues are an oddity, but back then they were an essential part of many players’ rise. Sixteen eventual Mets — including Moock, Shaun Fitzmaurice, Al Schmelz, Dennis Musgraves, Gary Gentry, John Stearns and Bob Apodaca — honed their skills in South Dakota’s Basin League, an amateur summer circuit which began in 1953 and lasted until the early 80s. (Jim Palmer, Bob Gibson and Frank Howard were Basin League vets.)

For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3. For some ballplayers, release from a pro contract wasn’t the end of their careers — which led to encounters with guys whose time as pros had yet to begin. As a kid, I loved the story of Tom Seaver‘s disdain for the narrative of the Mets as lovable losers. “I’m tired of jokes about the old Mets,” Seaver told the writers as spring turned to summer in 1969, then added: “Let Rod Kanehl and Marvelous Marv laugh about the Mets. We’re out here to win.” What I didn’t know was that Seaver was doing more than channeling franchise lore. In 1965 he’d been part of an intimidating Alaska Goldpanners starting staff alongside future teammates Danny Frisella and Schmelz. In the semi-finals of the National Baseball Congress championship, Seaver started against the Wichita Dreamliners, whose roster included Kanehl and his fellow ’62 Met Charlie Neal. Kanehl opened the game with a triple and stole home; Seaver and the Goldpanners lost, 6-3.

Another independent circuit, the Mandak League, thrived in the 1950s as a haven for former Negro League players and African-American and Latin players who’d been driven out of pro ball or refused to put up with the abuse required to stay in it. Before he turned pro, Sammy Drake had a tryout with the faded yet fabled Kansas City Monarchs and got his start in the Mandak League as a Carman Cardinal, a move he made in part on advice from older brother Solly, who told him the largely Canadian league was an easier place to play than the South. After signing with the Cubs, Sammy Drake joined Ernest Johnson as the first black players for the Macon Peaches, and learned all too well what Solly had warned him about.

Race kept some players from the big leagues or delayed their arrival — ask Ed Charles or Al Jackson about that — but players also had to deal with farm systems that were ill-suited for developing young talent. Baseball didn’t dismantle its bonus-baby rules until ’65, and countless careers were short-circuited by bringing players up too early and then leaving the shell-shocked rookies to rot on the bench or in the bullpen. As if that wasn’t enough, players could be undone by internal politics, skullduggery designed to thwart other organizations, or simple incompetence.

Before I started my insane project, Jerry Hinsley was half of a Met rookie card, the less-than-proud owner of a 7.08 ERA in 11 career games. But Hinsley went 35-0 as a high-schooler in Las Cruces, N.M., helping his team to three straight state championships and throwing three no-hitters along the way. The Pirates signed him (with twin brother Larry for company) for 1963, but wanted to keep him from being taken in the first-year draft. So they sent the 18-year-old to Kingsport, Tenn., and told him to pretend he had a sore shoulder. Hinsley didn’t pitch a single inning all year.

Mets scout Red Murff knew about Hinsley and wasn’t fooled. The Mets drafted the young pitcher and found a new way to abuse him — they had him make his pro debut in the big leagues. Hinsley racked up an 8.22 ERA before he was sent down at the end of May, made it back to the majors for a ’67 cup of coffee and retired at the end of ’71 — still just 26 — as an Indians farmhand. If he’d been treated differently, who knows what might have been?

Misfortune destroyed other careers. Dennis Musgraves threw two no-hitters in college and signed a then-record $100,000 bonus with the Mets in ’64. Rushed to the big leagues in July ’65, he followed three strong relief appearances with a seven-inning start against the Cubs in which he allowed just one earned run. The next morning his elbow was swollen and his pitches couldn’t reach the catcher. He’d endure two elbow operations and remake himself as a junkballer, but never returned to the big leagues — his 0.56 ERA will forever be a what-if. Ditto for Dick Rusteck, whose big-league debut was a four-hit shutout against the Reds in June ’66 — followed by a hurt shoulder and a bad elbow. Unfortunately for the likes of Musgraves and Rusteck, Frank Jobe was nearly a decade away from trying a novel surgical procedure on the left elbow of Tommy John, and most sore arms were professional death sentences.

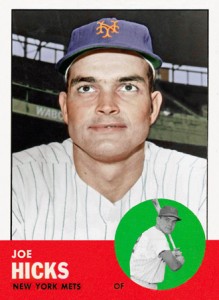

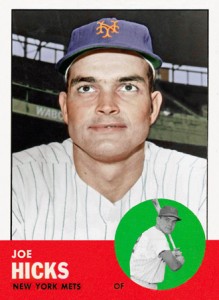

Joe Hicks, who hit .226 for the ’63 Mets, never had one big thing go wrong for him — just a succession of small and medium-sized things. Hicks was signed by the White Sox out of the University of Virginia in 1953 and hit .389 for Madisonville in the Kitty League, finishing the year with a .346 average for Colorado Springs. He hit .349 the next year, then .299 for Memphis in ’55. He was 22 years old, one step from the majors, and Chicago needed outfielders.

Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape. Then Hicks got drafted. He spent two years in the army, playing ball in Frankfurt instead of Comiskey Park. When he came back he was rusty, and the White Sox were soon a championship club. Hicks’s chance to crack their lineup had gone; he made the majors, but never got regular playing time — he was on the White Sox roster for most of 1960 and only collected 36 at-bats. He’d become a pinch-hitter and extra outfielder, roles he’d never escape.

Then there were guys whose highlights came before their debuts — sometimes on bigger stages than you might guess. Ted Schreiber was born in Brooklyn, grew up a Dodgers fan and went to St. John’s. In 1958, with the Dodgers gone, Ebbets Field was home for a handful of Long Island University and St. John’s games. On April 24, Schreiber hit a game-winning two-run homer there. Five years later, he’d play at the Polo Grounds as a Met.

Or take Shaun Fitzmaurice, who’d have given Michael Conforto a run for his money in the hype department if we’d had Twitter in 1966. Fitzmaurice had power and speed that made scouts compare him with Mickey Mantle. While a Notre Dame student in 1963, Fitzmaurice slammed a 500-foot home run against Illinois Wesleyan that’s lived on in college lore. USC coach Rod Dedeaux — who’d help shape Seaver’s career — took Fitzmaurice as an Olympian for the 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo, and he hit the game’s first pitch for a homer.

Fitzmaurice never hit a Met home run, but this one almost counts: In 1961 he played for the U.S. All Stars in the Hearst Sandlot Classic at Yankee Stadium. With two out in the ninth, Fitzmaurice drove a ball 400 feet, tearing around the bases for a two-run inside-the-park home run. The teammate he drove in? U.S. All Stars’ second baseman Jerry Grote, whose double-play partner for the game was Davey Johnson.

One story left me happy about what was instead of wondering what could have been. It’s the tale of Bill Graham, briefly a Tiger and Met. All I knew about Graham was that he shared a name with the rock promoter and always looked like his hat didn’t fit. But there was a lot more to him than that.

The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case. The first oddity about William A Graham Jr. showed up in his statistics: Following five uninspiring years in the Detroit system, he didn’t pitch at all in 1962, 1963 or 1964. I thought perhaps he’d been in military service, but that wasn’t the case.

Graham, the son of a Flemingsburg, Ky., physician, had stepped away from baseball to become a doctor. He completed his degree at Elon College in North Carolina in 1962, then went to medical school at UNC and the University of Kentucky. He came back to baseball at 28, won 12 games for Syracuse in ’65 and helped Mayaguez to a winter-ball title. He was older, wiser and far from the typical prospect.

“I’m at an age now that another year in baseball won’t make any difference, except to steer me either way,” he told a reporter during 1966 spring training. “The hardest thing is to get into medical school, and I worked too hard not to take the opportunity. I like baseball and I’ll see what happens this year.”

What happened was that Graham pitched well in a second go-round with Syracuse and made his big-league debut in Detroit’s final game of 1966. Next August, after a 12-6 season with Toledo, he was purchased by the Mets. Graham made three starts for the Mets; on September 29 he scattered six hits in a complete-game victory against the Dodgers.

It was Graham’s first big-league win. It was also his last professional appearance.

What happened? William A. Graham Sr. was ill, so his son went home to Flemingsburg to care for him. The younger Bill Graham missed the ’69 World Series and the chance to build on an intriguing story.

Or rather, he missed the chance to build on that story.

Graham did well back home in Kentucky. He farmed, developed land and became a mainstay of local government and business, serving on any number of boards and commissions. When he died in 2006, he left Elon a $1 million bequest.

“You spend your life gripping a baseball,” Jim Bouton famously said, “and it turns out that it was the other way around all along.” Not for Bill Graham, though. He approached baseball differently, coming and going on his own terms, and it worked out pretty well.

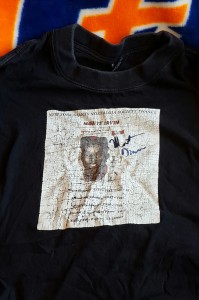

by Greg Prince on 18 January 2016 4:49 pm “Monte Irvin died,” I told my wife last week.

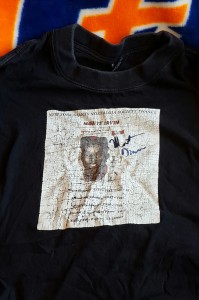

“Aw, the man on the shirt?” she asked.

I have a t-shirt that features a likeness of Monte Irvin’s 1954 baseball card, along with a bullet-point bio, his actual autograph and the thanks of the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society for giving his time to the group. I don’t wear it too often because it’s a little thick in the fabric, plus I never wanted to spill anything on him. He’s Monte Irvin. He’s in the Hall of Fame.

Well worn, well loved. And he’s the man on the shirt. You live almost 97 years, you’ll be known to different people for different things. When you’ve lived that long and accumulated fame, a torrent about your life will come to light on the occasion of its inevitable conclusion.

There was a lot of Monte Irvin in the news last week. It’s sad that it takes death to shine a spotlight on a person long out of the news, but the consolation, particularly as regards someone who shall we say got his money’s worth in the longevity department, is we find ourselves thinking, hearing and talking about that person. Monte Irvin made the back page of the Daily News the day after his passing became known. It wasn’t the main story (the previous night’s Knicks game was), but it did earn mention above the flag, complete with head shot.

BASEBALL PIONEER

N.Y. Giants Hall of Famer Monte Irvin dies at 96: Pages 46-47

You have to have been some kind of someone to make the back page of the Daily News as a New York Baseball Giant in 2016.

The first time I encountered Monte Irvin was in the 1972 Mets yearbook, page 56. He was part of a spread devoted to the previous season’s Old Timers Day at Shea Stadium, a 20th-anniversary celebration of the 1951 Giant-Dodger pennant race. At the time, most of the principals from that “epic” (as the yearbook referred to it) were still around, as were myriad New Yorkers who had celebrated/mourned it first-hand. Bobby Thomson and Ralph Branca showed up at Shea, as did Sal Maglie and Carl Erskine, Eddie Stanky and Pee Wee Reese, and a slew of other names that evoked an earlier era. Giants skipper Leo Durocher was in the middle of the festivities, thanks to the Mets playing the Cubs, his 1971 employers. And in his own box, on the lower left quadrant of the left-hand page, smiling up at me from the first-base dugout, his right foot on the top step as he awaited introduction to more than 43,000 fans, “Monte Irvin: a giant among ’51 Giants.”

I had no idea who he was. I was nine when I received my first Mets yearbook. I was only then processing that these Giants and Dodgers, dressed in uniforms that looked familiar but wearing caps that had unexpected insignias (NY? B?), were the forebears of the Giants and Dodgers over in the Western Division. These photos might have been my introduction to the “shot heard around world,” as a caption called it. Whatever role Monte Irvin played in perhaps the most heated battle any league ever experienced for its championship — 24 home runs, 121 runs batted in, .312 batting average — was unknown to me. I just knew he got his own box and he was termed a giant among Giants, so I figured the man in the picture must have been pretty special.

Within a year of my brief but effective history lesson, the Hall of Fame confirmed his status, inducting him in 1973. Irvin’s major league totals looked light, but there was an explanation. Irvin was black. He played much of his career in the Negro Leagues, much like Satchel Paige, another guest at the 1971 Old Timers Day (identified as “legendary,” “ageless” and “Satch,” the yearbook showed him giving a “grip tip” to an attentive Tom Seaver). The best of those African-American players, the ones who were kept out of the big leagues before 1947 yet started entering the Hall as of 1971, couldn’t help but be presented to us as an incomplete story. The white players had statistics you could look up. You knew that Babe Ruth hit 714 home runs, that Cy Young won 511 games, that Walter Johnson struck out 3,508 batters. I know those numbers without looking them up. They were ingrained into the impressionable baseball fan mind at a young age. The numbers told all the story you needed in terms of their qualifications for the Hall.

But for Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard and Monte Irvin and others who were barred from the majors for most or all of their baseball careers, we had to take the word of those who went to the trouble of digging beyond readily available numbers. These were players so astounding that they transcended the relatively smooth path to Cooperstown taken by Christy Mathewson or Honus Wagner. It wasn’t a snap to pore over their stats and judge, “oh, he’s a lock.” Monte Irvin hit 99 home runs during seven seasons as a Giant and one as a Cub, all of them after the age of 30, yet he’d been playing professionally since he was 19: eight years as a Newark Eagle (along with a stint in Mexico), sandwiching three years in the army during the Second World War.

Monte Irvin served his country, then had to wait four years to be allowed to compete at what was considered the highest level in his profession, a profession in which as you age past a certain point, you generally don’t keep getting better. Irvin’s prime fell victim to racism. That’ll shave some points off your totals for sure.

With Irvin’s passing came two seemingly universal testimonies: 1) he was a great player who was an even greater person; 2) he was a great person, but don’t overlook how great a player he was. As people who love baseball, we are taken by the notion that he was good enough to be tabbed an immortal without the usual set of easily verifiable stats. As fellow human beings, the idea that he possessed an exceptional grace should impress us all.

Other details tumble to the surface upon a person’s passing, items that by no means defined the deceased but tend to get our attention. It’s stuff you might have encountered a while back but had mostly forgotten or perhaps stuff that you never knew. For example, Monte Irvin worked for two years as a scout for the New York Mets, in 1967 and 1968. He spent many years before that in community relations for Rheingold, the official beer of our favorite team. Later, from 1968 through 1984, he worked in the commissioner’s office, roughly spanning Bowie Kuhn’s term of office. Irvin traveled to Atlanta to represent Major League Baseball on April 8, 1974, the night Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run. Kuhn begged off, citing a previous engagement. The commissioner should have been there and the crowd knew it. They booed when Irvin was introduced. The boos were directed toward the man who wasn’t in attendance.

Thus, the man who mentored Willie Mays as a kid new to New York offered official congratulations to Henry Aaron as he became an American icon. Mays and Aaron, like Irvin, began their careers in the Negro Leagues, but they were relatively fortunate to come along when they did. Their wait to make the majors wasn’t nearly as unjustifiably long.

Here’s a tidbit you might not know. For one season, Monte Irvin was Bob Murphy’s broadcast partner…calling New York Jets games. Murph was a pro’s pro of an announcer and Irvin was an all-state high school football player in New Jersey who went on to star for Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (turning down an offer from the University of Michigan for financial reasons; he couldn’t afford the train fare). It sounds odd, but it made sense; Bob Murphy and Monte Irvin brought all the Jets action to radio listeners in 1963, the franchise’s first year as the Jets, their last year playing in the Polo Grounds.

The Polo Grounds, where Irvin made his name for the Giants once the powers that be permitted him the opportunity, was on its last legs. The Jets, like the Mets, were headed to Shea Stadium, where Monte would pose for a photographer in 1971 and inadvertently introduce himself to me. On paper, Shea was supposed to have been open by now for baseball and football by 1963. On the ash heap upon which it was being built, construction moved at its own deliberate pace.

Ground was broken on Shea Stadium on October 28, 1961. I don’t know if that was really when the building had begun. The Mets didn’t break ground on Citi Field until November 13, 2006, yet work had commenced the previous June. The ceremonial aspect came later. You have to have ceremony when you’re creating a new home for a new team. It was essential that dignitaries be called upon in 2006 to make a whole thing of it, just as it was in 1961.

And such dignitaries, as a Pro Football Researchers Association article from 1990 article recounts. Out in Flushing were gathered municipal officials like Robert Moses, team executives like George Weiss, the commissioner of baseball Ford Frick, Mayor Robert Wagner and, to properly consecrate the Queens meadows, a handful of baseball players. A couple of Dodgers. A few Giants. Given the Mets’ charge of succeeding the dearly departed, the casting couldn’t have been more appropriate.

The invited players included two Dodgers who were going to become Mets in 1962 — Gil Hodges and Billy Loes — and three Giants who were by 1961 retired: Sid Gordon, Jim Hearn and, yup, Monte Irvin. Irvin, then 42, was one of those who grabbed a shovel, scooped up a clump of dirt and ceremonially set the stage for the ballpark we’d call ours for 45 seasons, the stadium the man would outlive for seven seasons after that.

It was hardly his greatest accomplishment, but it’s the one that’s made me the happiest in the wake of learning such sad news.

by Greg Prince on 7 January 2016 1:59 am Recognized validation of Mike Piazza’s baseball immortality came in our man’s fourth appearance on the Hall of Fame ballot. If you put aside the fact that it didn’t take Mets fans four freaking election cycles to figure out Piazza was among the best of the best of all time, it sounds sort of appropriate.

Mike Piazza did some of his most dramatic work his fourth time up. Seventh, eighth, ninth inning, depending on how the game was going. If it was close and Mike was coming to bat, we didn’t think it was over. We had Mike Piazza. We had every chance in the world.

There was no reason to give up when Mike Piazza was a Met. There was no reason to give up when Mike Piazza was a Hall of Famer in waiting. If we learned anything between 1998 and 2005, it was you could never count out Mike Piazza.

Count him in now. Count him in among the Class of 2016 in Cooperstown. Count him in among those fourteen players who have been Mets and who have been certified Hall of Famers, even if their days in our duds were relatively brief and totally incidental to their case. Count him in (by every available indication) as the second Met to — per the lexicon of the realm — go in as a Met.

There’s Tom Seaver. And now there’s Mike Piazza. I’ll take that battery any day.

I can’t stress enough that Mike should have received this honor in 2013, when he was first eligible. I can’t stress enough that it was borderline irresponsible for 75 percent of Baseball Writers Association of America members to not vote for the greatest-hitting catcher who ever played the game. I can’t stress enough how insulting the whisper campaigns that kept him out were. I can’t stress enough that as long as we cherished Mike’s eight sublime seasons in our midst, it didn’t ultimately matter if more than 25 percent of voters in a given year found him something short of worthy.

I also must confess that those gripes carried an expiration date of January 6, 2016, the Wednesday it was announced Piazza, along with Ken Griffey, Jr., was finally getting his impeccable credentials validated. I’m probably a bit of a hypocrite for having gotten hung up winter after winter on Piazza’s omission — how glad I am that we have been successfully relieved of partisan Cooperstown sentry duty — and now deciding this is a moment to celebrate.

But it is. One of ours is heading to the Hall. Thirteen prior Mets have made it there, but really, it’s happened fully only once before. That was for Tom Terrific. When Seaver — still possessor of the highest percentage of Hall of Fame checkmarks ever made on behalf of any pitcher — got the call this week in 1992, it was as if we’d won an additional championship. The victor was Tom, the emotional spoils were ours. That feeling visited me again Wednesday night. That’s the connection at work. That’s why we say “we”. That’s why we dwell on an insignia on a plaque whose path it’s quite possible we’ll never cross.

This is not an occasion to wonder why we invest ourselves in individuals we likely won’t meet and certainly won’t know in any substantive fashion. This is a time to simply bask in a veritable eternal glow.

The glow was warm that Friday afternoon in late May when the word went forth that the Mets had traded for Mike Piazza at the end of his Florida Marlins layover. My phone rang several times. I rang several phones. We, Mets fans, had to share the news with us, more Mets fans. Didja hear? We just got Mike Piazza! It didn’t matter for who or for how long. You get Mike Piazza, you revel first, you ask questions later.

Later, much later, on an early-October Sunday afternoon in Flushing, the glow was still warm. The years hadn’t dimmed our enthusiasm for the news and the knowledge that we had gotten Mike Piazza and we had held onto Mike Piazza and Mike Piazza had kept us looking forward to his every last at-bat, right up to his literal last at-bat as a Met.

In between the acquisition of May 22, 1998, and the au revoir of October 2, 2005? The glow…the warmth…the electricity of knowing we had Mike Piazza and he was going to be up a fourth or a fifth time in whatever game was going on, quite possibly the biggest game we could imagine finding ourselves in, desperately needing one more hit. Maybe we were down, but we were never out. Piazza was stepping to the plate. There was a pitch; there was a swing; there was another instance of a surefire future Hall of Famer coming through for us. If we were on hand, there was some serious high-fiving and backslapping and hugging. If we were following alone from afar, we whooped and we clapped and we were as thrilled as could be.

The thrill continues unabated that Mike Piazza is Mike Piazza of the New York Mets, now Mike Piazza of the New York Mets in the Hall of Fame. I’m amazed every single day he’s one of ours.

by Greg Prince on 6 January 2016 3:18 am “He called me when we won the division, congratulating me. I tried to return the call, but it’s like getting through to the President when you call the Giants. So I didn’t get through.”

—Terry Collins on playing phone tag with Tom Coughlin, October 21, 2015

The crotchety and the crusty have lost one of their champions. Fortunately, we enjoy a regional surplus.

Tom Coughlin is no longer the head coach of the New York Football Giants, as they still charmingly like to be known. Coughlin either resigned or took an enormous hint and beat John Mara to the dismissal punch. Twelve seasons during which the Giants and their fans never had to wonder who was calling the shots on the sidelines are over, two Patriot-crushing Super Bowls notwithstanding. Glittering accomplishments and a sterling reputation only get you so far “after you go 6-10 twice,” Coughlin himself suggested.

The Lombardi Trophies made Coughlin lovable. Before his teams earned them, he came off as a certifiable crank, screaming at kickers and ostentatiously missetting clocks. Once he won a title, we realized he was the salt of the earth. When he won another, he was surely saintly. Missing the playoffs over and over overrode all of those admirable attributes in the eyes of his employers.

Good thing New York keeps a TC in reserve.

“He kind of reminds me of me, to be honest,” Terry Collins said of Tom Coughlin during the National League Championship Series, and probably not just because neither of them looks fully dressed without a baseball cap on his head.

Collins — with whom Coughlin developed an October simpatico that transcended mere initials — could have been mistaken for a cantankerous coot two missed anger-management classes from a meltdown when he came to town five years ago. Now, with a pennant under his belt, he drips common sense and leaves puddles of wisdom in his wake. MLB Network will next week (January 12, 9 PM EST) present the Mets’ manager in documentary form. Terry Collins: A Life In Baseball, is said to feature “his first comprehensive television interview since the 2015 World Series,” during which he “opens up” on the depth and breadth of “his baseball journey,” a trip it’s safe to say there was a far more limited audience for a year ago.

Winning makes everybody more interesting, apparently. Tom Verducci wasn’t sitting down to get Terry Collins’s thoughts on dinner let alone his influences until Collins attached himself to a pennant. Winning also keeps you positioned to potentially win more, just as losing can remove your chance to turn around those nasty 6-10 records. There are exceptions. Collins didn’t win as many as 80 games in a 162-game schedule for four consecutive seasons, but the Mets, for better or worse, weren’t leaning heavily on results between 2011 and 2014.

Terry piled up his tenure and embellished it meaningfully in 2015 to bring it to a point where he’s in position to outlast every Met manager before him.

Unless something goes terribly awry, Collins will fairly soon have managed the most games in franchise history.

You read that right. Terry Collins, erstwhile professional caretaker for a ballclub on a budget, is on the verge of becoming our John McGraw, our Connie Mack, our Steve Owen (the only head coach to endure longer than Tom Coughlin for the New York Football Giants).

Admittedly, it doesn’t take much to be the Mets’ all-time leader in anything smacking of longevity. We are traditionally Kranepoolian and little else in that regard, managers being no exception. Tragedy prevented Gil Hodges from lasting as long in the job as he deserved. For everybody else, it was a matter of too many losses or too little patience.

Terry, for the time being, has turned the losing around and hasn’t expended the goodwill of the powers that be. Thus, he has racked up 810 regular-season games — and 14 in the 2015 postseason — as Mets manager, placing him third among all Mets managers, not very far behind Nos. 1 and 2 on the list.

Davey Johnson managed 1,012 games between 1984 and 1990 plus 20 in two Met postseasons. Bobby Valentine was at the helm for 1,003 contests from 1996 through 2002 along with 24 postseason dates in 1999 and 2000. Then comes Collins.

If he doesn’t go before approximately Memorial Day 2017 (and he’s signed for two years), Collins will surpass Valentine, then Johnson. He will be the longest-serving manager in Mets history.

No, really. It’s hard to wrap one’s uncapped head around that. It’s not that Terry Collins was a particularly incapable manager to begin with. It’s just that he seemed so…disposable. Most managers are, especially Met managers. Consider Hodges (clearly and sadly a special case), Yogi Berra, Johnson, Valentine and Willie Randolph — the five managers prior to Collins who led Mets teams to the playoffs. Now consider the total number of games they managed for the Mets once they were two years removed from managing their final postseason Met game — zero.

Given Collins’s relatively advanced age (66) and the Mets’ generally raised expectations, it’s possible he won’t have much of a Flushing coda beyond his final October appearance, though we can always hope that means he goes out on top as Tony La Russa did in St. Louis, definitively calling it quits after winning a World Series. Then again, Coughlin is 69 and by no means referring to his resignation as a retirement. Most coaching types have to be kicked upstairs or out…just like the rest of us.

Tom Coughlin will put out feelers. If he steers clear of the NFC East, those of us who root for his old team when there’s no baseball on can’t help but wish him well. Meanwhile, the New York Football Giants search for his replacement, a process necessarily fraught with uncertainty. Remember uncertainty? Remember the fall of 2010 when the Mets were sorting through a slew of candidates only to wind up with the unlikely choice of a manager who hadn’t been active in the majors since the 20th century, someone who was drummed out of his last clubhouse by his own players? How long would Terry Collins last in New York?

Long. That’s how long.

by Greg Prince on 2 January 2016 3:20 am The lamentably late Natalie Cole told us in good old 1975 what This Will Be, but she wasn’t necessarily* in the forecasting business. It’s a blank slate out there. The new year couldn’t be much newer or less knowable. If you need precedent (despite precedent’s limited efficacy), just look back to 365 days ago. We had no idea what the Mets were about to do and only modest concept of who was going to do it for them when 2015 began. Counting on 2016 to reveal its mysteries at the outset is an exercise in assumption. No matter how informed yours is, I refer you to Felix Unger’s courtroom chalkboard as to what will be made of “u” and “me” should you rely too heavily on it.

You could say the same about life in general, but let’s keep our eye on the literal ball here. If you want to say, “This season will be…” and fill in the rest, knock yourself out. You’re probably gonna get it wrong. Or you’ll accidentally get it right. How the hell would you know what’s coming next? Or how would I?

We’ll guess anyway. We’ll even assume, potential for “ass” notwithstanding. I’d suggest taking your own projections and predictions lightly. Give the players you’re certain are going to fizzle a chance to surprise you. Give the benefit of the doubt to everybody in January. We’re tied for first for another 92 days. Enjoy it.

And maybe revel in the fact that we’re in the midst of the shortest offseason in Mets history. Usually at the dawn of a new year, we’d be hitting the Baseball Equinox, the instant at which we are equidistant between the last pitch of the previous season and the first pitch of the upcoming season.

The previous season extended itself quite nicely, you may recall. Thus, because the Mets weren’t finished with 2015 until 12:34 AM on November 2 (I checked the time; it was better than watching the Royals), we have yet to Equinox. The midpoint — that moment when we’re rounding second and heading for home — will arrive on Sunday, January 17, at approximately 10:34:30 PM EST. When the clock strikes that, you’ll know we’re on an inevitable glide path to Sunday, April 3, at 8:35 PM EDT.

Ah, call it 10:35 PM (or 10:05 PM if you want to be a stickler for the hour we lose on March 13 not being offset by the fall-back hour we gained before the World Series was over). First pitch on Opening Night is at ESPN’s discretion, and between them and whatever unwatchable ceremonies are wrapping up at Kauffman Stadium, figure everything starts at least 30 seconds beyond when it is supposed to.

Not that there’s much concrete “supposed to” for a baseball season three months in advance.

*Instead of that corny “the bride feeds the groom” tune, we played “This Will Be” at our wedding to accompany our ritual cutting of the cake. “This will be/an everlasting love,” Miss Cole sang for Stephanie and me nearly a quarter-century ago. I’m gonna say she was on target with that prognostication. R.I.P. to a singer whose voice remains an everlasting gift to us.

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2015 3:40 pm Happy 1975 everybody! No, I’m not daft, but I realize with less than one day left in 2015, the opportunity to write a milestone remembrance of one of my favorite Met years is about to expire. I could write about 1975 in 2016, but that would be the 41st anniversary and even though 41 is an awesome number in Met circles, it just doesn’t work that way.

So because 1975 + 40 is about to end — and because today is my birthday (the 40th anniversary of the one when I turned 13) — I’m going to celebrate what the Mets did in 1975.

Tom Seaver won 22 games.

Tom Seaver won the Cy Young award.

Tom Seaver struck out more than 200 batters for an eighth consecutive year.

Tom Seaver was my favorite player and the best pitcher in baseball.

Randy Tate, whom I’d never heard of before 1975 and who’d never pitch in the majors again after 1975, won five games, not including one in which he nearly threw a no-hitter. He went 5-13, but I’m still thinking fondly of him four decades later.

Jon Matlack was the All-Star Game co-MVP. He shared it with Bill Madlock, which seems like a typographical precaution.

Jerry Koosman saved two games, stole second base once and lost as many games as Randy Tate. He went 14-13.

The Mets went 82-80 (I like how pitchers and teams “go” and “went”), which was an eleven-game improvement from 1974, which was the first losing season I ever experienced and, maybe not coincidentally, the last season that I have significant holes in my specific recollections of. I decided to be very excited about 1975 in advance and stayed immensely engaged in their activities for 162 games.

The 1975 Mets subtracted Duffy Dyer, Ken Boswell, Ray Sadecki, Teddy Martinez, Don Hahn, Dave Schneck and Tug McGraw before it ever became 1975. They added Gene Clines, Bob Gallagher, Joe Torre, Jack Heidemann, John Stearns, Mac Scarce and Del Unser as a direct result. That’s what got me excited.

Then they added Dave Kingman as Spring Training was beginning. Now that was exciting.

Dave Kingman broke Frank Thomas’s single-season Met home run record. It had been 34 since 1962. I accepted that 34 home runs by a Met was the equivalent of 48 hit for a player on a team that hit home runs as a matter of course…which was something the Mets simply didn’t do. The idea that 34 could be exceeded was as mind-boggling in its day as it was that any Met — Randy Tate or otherwise — could throw a no-hitter.

Tom Seaver nearly threw a no-hitter in 1975, but he lost it with two out in the ninth to Joe Wallis and, besides, the Mets hadn’t scored yet, so even if was a no-hitter, it wasn’t necessarily going to be a no-hitter.

Dave Kingman hit 36 home runs.

Dave Kingman played first, third and the outfield. He was what was considered versatile. He played none of those positions gracefully or particularly skillfully. But who cared? He hit more home runs than Frank Thomas.

Rusty Staub drove in 105 runs. Another inconceivable total. Donn Clendenon had held the team record of 97. Rusty shattered it.

Kingman: 36 homers! Staub: 105 RBIs! Seaver: a conceivable/excellent 22 wins!

Why were the Mets only two games over .500?

Ah, it doesn’t matter 40 almost 41 years later. What matters is Unser (batting close to .300 at midseason) should’ve joined Seaver and Matlack at the All-Star Game; that Felix Millan played in all 162 games; that Ed Kranepool batted .400 as a pinch-hitter; that Bob Apodaca was a better closer in the first half than McGraw was for the Phillies; that Mike Vail — a throw-in with Heidemann — hit in 23 consecutive games as an August callup; that Mike Phillips (a .342 hitter in his first 22 Met games), Jesus Alou (.350 as a pinch-hitter); Ken Sanders (who was terrific out of the pen before and even after getting hit in the eye by Stearns’ errant return of a warmup pitch), Tom Hall (who wasn’t terrific out of the pen for very long, but was a former Red, and they were good) and Skip Lockwood (a 1.49 ERA in 24 appearances, including a save in the team’s 82nd win, which clinched them a piece of third place and a memorable World Series share) all came along as the year progressed. They were veterans I’d heard of and their presence made me think the Mets couldn’t help but get better…just as I was sure Heidemann and Gallagher and Clines and so on were going to improve the Mets something fierce.

They were improved. They won eleven games more than in ’74. They stayed relatively close to first place during the summer and edged to within four games of first in early September. It didn’t take, but I believed.

I was 12 going on 13, so you couldn’t tell me different.

I was 12 and watching or listening to the Mets every day and reading about the Mets in everything I could find and thinking about the Mets most of the time.

Just like when I was 52 going on 53, I suppose.

And 42 going on 43.

And 32 going on 33.

And 22 going on 23.

I’m either in kind of a rut or Amazin’ly consistent.

It’s always been fun, but it was, on some level, as fun as it ever was or would be in 1975. Give me an OK Mets team that has kind of a chance and a handful of players doing extraordinary things and I’ll still be warmed by their very existence 40 going on 41 years later.

There was a song out that season: “Old Days” by Chicago. It was reflective of somebody else’s nostalgia. I was too young for nostalgia. To my mind, I was living in the greatest baseball season I’d ever lived through, all things considered, yet I identified with “Old Days” immediately. Maybe I was taken by the lyric that listed “baseball cards and birthdays” among the things the narrator wistfully longed for.

My birthday wouldn’t be until December 31, but by the time I first heard “Old Days,” probably in May, I’d managed to secure most of the 660 cards Topps had released in 1975. Baseball cards were at the center of my life and now they were mentioned on the radio at regular intervals.

The world was coming around to my way of thinking.

The day 1975 ended, the day I turned 13, I might have had an inkling it was never going to be the same again. That wasn’t to say it wasn’t going to be fine — it would just be different. “Twelve years old” had a ring to it. “Thirteen,” impending Bar Mitzvah notwithstanding, was supposed to be unlucky. Once 13 got going, it was all about getting to 14. I had my first facial hair at 13, the slightest hint of a mustache. People expected you to know more and more things as you got older. At 12, knowing about baseball was enough.

Plus, just before I turned 13, the Mets traded Rusty Staub for Mickey Lolich. The world was definitely getting more complicated.

Twelve became Old Days pretty quickly. I asked for one birthday present at 13: The Sports Collectors Bible by Bert Randolph Sugar. Thing is, I never collected baseball cards with quite the same enthusiasm again. I wouldn’t be quite so optimistic about how the Mets were going to do in the season ahead for almost another decade. By then, former youngsters Gary Carter of the Expos and Keith Hernandez of the Cardinals were grizzled Mets. Mike Vail, who never exceeded his late 1975 exploits, was retired. Rusty Staub was somehow back with the Mets but not driving in 105 runs. Tom Seaver somehow wasn’t a Met and had never again won as many as 22 games in a single season or another Cy Young.

The next time I was incredibly optimistic about the next Mets season, it was 1985, which was 30 years ago and is about to be 31, which is also a pretty special Met number, but those are other stories for other times.

I hope this time that we’re in now, 2015 going on 2016, is breaking records for all of you. I really hope that some Mets fan who was 12 this year that the Mets improved by eleven wins (from 79 in 2014 to 90 in 2015) finds himself down the road looking back and remembering how great it was then, that year the Mets won the pennant.

And when he’s down that road, I hope he still finds himself excited over how great it can be every year.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2015 4:44 pm With Faith and Fear’s tenth-anniversary year coming to an end, I thought this would be a handy occasion to round up the series of ten articles I wrote to reflect upon our 2005-2015 milestone and revisit their subject matter a bit.

1. Madoff Changes Everything (March 9)

You know what I like to write about? Baseball. One of my favorite things is to look at the Mets and try to figure out whether their team is good enough to win, and if it isn’t, I like to puzzle out what might be done to make it better. We all do this. Except every time I’ve attempted to do this for the past six or so years, I hit a brick wall. Every meditation on the near-term fortunes of the Mets inevitably devolves into some version of “…but we don’t really know how much the Mets can spend, so who knows what’ll actually happen?” That’s the legacy of “Bernie Madoff” in the Met sense. It used to be we knew. We grasped whether the Mets had resources (it was more or less a given that they did) and by their actions they let us know what they planned to do with them. Maybe the Mets spent them wisely or foolishly, but you could follow along at home. When we began blogging in 2005, they had resumed spending enthusiastically. It produced a fun ride for a while. Then Madoff happened. Actually, I suppose Madoff happened before. Madoff happening — not the part where he was caught, but the part where he seemed to be a wizard and the principal owner trusted him implicitly — meant the Mets acted as if they had resources they didn’t necessarily have. Or they had them before they didn’t. See, I still don’t quite get it.

Update

I still don’t get it, but I came away from 2015 with more respect than ever for the job Sandy Alderson and his front office do to work within the still murky parameters of the Mets’ budget limitations. It’s not ideal, but it produced a pennant.

2. The Four Aces (March 18)

A funny thing inevitably happens on the way to where these aces are supposed to be taking us. Pedro was The Man in practice for a year-and-a-half before sputtering in and out of the rotation for the rest of his four-year deal. Johan, who closed out 2008 with such a flourish, was never around for the close of a season again, including two seasons when he was under contract but wasn’t around at all. R.A., given his beautiful pitch and unorthodox makeup, seemed a lock to be signed long-term. Instead he was traded. And Matt Harvey — calling him just “Matt” or just “Harvey” doesn’t seem appropriate in this context — was directed to the Tommy John table before his first full year was done. His second full year is scheduled to begin far behind schedule. Pedro and Johan and R.A. became history all too soon. But Matt Harvey has returned to make more of it. To make more good copy for us, too, which I will tell you, quite selfishly, ratchets up my interest in his aceness. Without a certifiable ace, you have to depend upon the achievements of mere mortals and work to find a hook 32 times a year. These guys who top rotations thoughtfully provide framework, fill in blanks, twist, turn, excel, elate and sprinkle our heads with content dust.

Update

We did get the fourth ace of the FAFIF era back in 2015. He drove us a little crazy as August became September, but boy were we glad to have him around come October. Even better is he’s not alone. I daresay “The Four Aces” will have a different, contemporary meaning if nobody gets hurt in 2016.

3. Jerry’s Kids Grow Up (March 22)

Seven guys who debuted as Mets under Manuel are still Mets [though] Manuel hasn’t been manager since October 3, 2010. Nobody’s much brought up Manuel since maybe October 5, 2010, the day he was officially not renewed for 2011. Nobody thought much of Manuel once his “gangsta” rap lost its ability to charm. He was the manager who kinda chuckled, kinda cackled in whaddayawantfromme? fashion after losses. He […] didn’t leave behind a legion of mourners when he chuckled/cackled for the final time. Turns out he may have left the Mets something better. He left them a legacy. He left them something close to a third of a roster for use a half-decade down the line. The team that is positioned to perhaps win more than it loses for the first time since Jerry Manuel took over from Willie Randolph has as its foundation Jerry’s Kids — now appearing in Port St. Lucie as Jerry’s Adults.

Update

The seven players in question — Daniel Murphy, Jon Niese, Bobby Parnell, Jenrry Mejia, Ruben Tejada, Lucas Duda and Dillon Gee — all played for the 2015 Mets. Three of the above have moved on to other organizations since the end of the season; one is suspended until the middle of the year; one more is a free agent. Only two of Jerry’s Kids — Duda and Tejada — are slated to be part of the 2016 Mets. Beyond patting the departees on the back and wishing them sort of well, we shall forever remember the October of Murph. Or we’ll try to keep it in mind the first time we see him in his new Walgreens uniform.

4. Year of the Stewed Goat (March 27)

I was vaguely aware that GourMets existed in its heyday […] but encountering it on the eve of 2015 was a revelation. I instantly fell in love with my second-hand copy of GourMets and, on some surprising level, I fell for the 2007 Mets all over again…maybe for the first time.

Update

An unexpected souvenir of the most star-crossed season in the FAFIF era allowed me to unclench a little when contemplating those 2007 collapsibles. Was it a sign that we were destined to cook up something better eight years later? However it happened, it is clear that we did.

5. Keep It .500 (March 31)

The Mets have played 1,620 regular-season games since we started. We’ve blogged something about every single every one of them. They’ve won 810. They’ve lost 810.

Update

On September 13, the Mets not only clinched their first winning season in seven years, but made certain that Faith and Fear’s all-time regular-season record would sit above .500 into our twelfth year. (It is currently 900-882.) For six seasons, I secretly enjoyed the challenge of writing about a losing team, but I can publicly affirm that I enjoyed far more writing about a winning team in 2015.

6. Three On A Mic (April 4)

Try to imagine these past six seasons without GKR. Try to imagine these past nine seasons, including the ones that weren’t mostly miserable from start to finish. The SNY booth made the Mets more Amazin’ when they were good and elevated them above intolerability when they were awful. Gary, Keith and Ron have given us Augusts that shouldn’t have been nearly as august and Septembers that we didn’t want to end no matter the tenor of the seasons barely any longer in progress. They gave us truth and insight and friendliness and intelligence and hilarity and baseball talk like it oughta be. They’ve been a talking miracle. They narrate the often sad and lame machinations of a franchise struggling to be less sad and less lame and have been encouraged and allowed to shine as if they’re nightly counting us down toward a magic number.

Update

The team turned around and the announcers remained, as Keith Hernandez would say, on point. The only danger from a blogging perspective is making a postgame article a summation of all the great things the guys said because their perspective informs so much of what we process. Sometimes, however, you can’t help going there at least a little.

7. Wrighthood (April 7)

Did it matter to David Wright that on his eleventh Opening Day, at Nationals Park, his manager decided to bat him second, somewhere he’d never been slotted on Opening Day or too often on any other days, certainly not recently? Does stuff like that ever matter to Wright? Or if it does, would he ever cop to it? “‘Terry,’” he said he told his manager during Spring Training 2015, “‘I don’t care. Just bat me wherever you think is best to help this team win, whether it’s second, third, sixth, seventh. It doesn’t matter.’ I don’t think it’s a big deal at all.” Thus, on April 6, 2015, David batted second in a starting lineup for the first time since August 31, 2010. Did it make a difference?

Update

David’s absence from the lineup made a helluva difference in the wrong direction after he went down with a mid-April injury. When he returned in late August, he came back to a transformed team — and just like he had every time his team changed around him from 2004 forward, he made a difference. The Mets’ bullpen cart of yore may have been auctioned off in 2015, but David Wright could have been chauffeured to third base in a Big Yellow Taxi. He is a classic example of not knowing what you’ve got until it’s gone.

8. Our Team. Our Time. (April 10)

They edged Washington to start their season. They lost in irritating fashion the next night. They finished off their opening series by sticking it but good to those pesky Nats. Welcome to 2015, which has kicked off exactly as 2006 did, if you take your parameters narrow (and if it helps, know that the Mets finish this year against the Nationals, which they also did in 2006). More to the point of this particular stroll down Has It Really Been Ten Years? Avenue, though, is that the above paragraph also describes the first three games of 2006, the best season to date of the Faith and Fear Era.

Update

I used to think it would be a very long time before we got to blog a season that was better than 2006. And it was. It was nine years. But 2015 set a new standard.

9. No Towel Thrown In (May 31)

Citi Field and I have had a strained relationship these past seven seasons. We grin and bear each other, all the while never truly feeling at mutual peace. It correctly senses deep down I’ve never forgiven it for succeeding Shea Stadium. Yet I’ve learned deep down that I can’t live contentedly without regular exposure to Shea Stadium’s successor.

Update

On the night Citi Field hosted its first postseason game, its probationary period finally ended. Welcome home.

10. Carry On My Sheaward Son (September 28)

Shea Stadium has finally stopped being present in my mind because it’s no longer present in the present. I still love Shea for what it was. I can’t love Shea for what it is. It’s not there anymore. A season like this and the postseason ahead, whether or not you change at Woodside, belong to Citi Field. The torch has been passed to a new configuration.

Update

Our World Class Ballpark not only got a World Series and all of its attendant ruckus, it also began to fall apart a little. No wonder I don’t need to miss Shea anymore. It’s beginning to feel like we never left.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2015 3:37 am It’s the one where Dick Clark is improbably playing himself as an afternoon drive time disc jockey on versatile WZAZ radio, and part of his gig is calling New Yorkers at random with trivia questions. The topic, he says, is opera, “which for you kids out is music with a lot of killing”. The number he dials belongs to one of the city’s best-known sports columnists.

What a coincidence!

I am describing, as some of you may have already inferred, “The New Car,” the sixth episode from the fourth season of The Odd Couple. It originally aired on ABC on Friday night, October 19, 1973, filling half an hour of space between Game Five and Game Six of that year’s World Series. The Mets were busy leading the A’s, three games to two, and things were looking pretty good, not just for New York’s favorite baseball team, but for the leading voice of the sports pages of the New York Herald.

Oscar Madison answered the three opera questions posed off camera by Dick Clark and won himself the new car alluded to in the episode’s title. Except he answered them with the help of his roommate Felix Unger, so he was ultimately compelled to share the car, which led to all kinds of car-related difficulties, considering Oscar and Felix resided at 1049 Park Avenue and parking in Manhattan, then as now, is always at a premium.

The most recent airing of “The New Car” occurred on Sunday night, December 27, 2015, over a channel called MeTV, which if read with extreme prejudice can be viewed as MetV. MeTV airs The Odd Couple every Sunday at 10 PM. I record it and watch it and enjoy it and, of course, keep an eye out for moments like Felix waking Oscar to tell him it’s his turn to alternate-side-of-the-street park the car. (Felix was up and dressed but wouldn’t move the car himself; he got up early just to see if Oscar would). Why?

Because in Oscar’s bedroom, a New York Mets pennant hangs limply above Oscar’s bed.

And when Oscar pushes himself out the door to move the car, he’s dressed in a bathrobe and a Mets cap.

That’s our Oscar. That’s who we celebrate at the end of every December when we hand out our annual Oscar’s Cap Awards in recognition of the year in Mets Pop Culture.

Our guidelines are loose. If we saw or heard the Mets infiltrate a movie or a television series or a song or a novel or a comic book or whatever, we mention it. And that’s the award. We strive to notice everything released ostensibly outside the world of sports and sports-related news in the preceding calendar year in which the Mets show up, but if we bump into something appropriate that was created years ago and we never knew of it or made proper note of it before, it gets an Oscar’s Cap, too. Though there are repetitious answers, there are no wrong ones.

So let’s doff our caps to Jack Klugman (and Walter Matthau) and hand out their character’s cap wherever we encountered the Mets when we weren’t expecting it.

2015 shared one overriding commonality with 1973, and it didn’t involve Dick Clark. The Mets won one of those things that hung from the wall in Oscar’s bedroom: a pennant. In this self-aware, self-generating pop culture age, that meant a dedicated tier of Mets creativity bubbled to the surface. I’m not sure that material created specifically to salute the National League champions qualifies as Mets Pop Culture in the truest sense, but how often do we win a pennant?

Here, then, is an honor roll of musical production numbers that strove to honor the 2015 Mets.

• Sara Davis Buechner gave a Gershwinian spin to “Meet The Mets” and created a virtuosic “Rhapsody In Orange And Blue”.

• Billy Joel, whose “Piano Man” scored eighth-inning breaks at Citi Field, broke out a bit of “Meet The Mets” at his monthly Madison Square Garden performance, the one in October that happened to coincide with Game Four of the National League Championship Series.

• Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) became an unlikely musical Mets booster when he sang our theme song on the floor of the House of the Representatives to settle a bet with Rep. Steve Israel (D-NY) following the Dodgers’ loss in the National League Division Series.

• James Flippin of WOR put the “Meet” melody to good use in a very 2015 version of the old favorite (“Conforto and Thor ain’t your average rooks/Howie Rose, holy smokes, put it in the books”).

• The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra brought an extra touch of class to an already classy anthem when they performed “Meet The Mets” on the plaza at Lincoln Center one frosty morning prior to the World Series. Special guest conductor: Mr. Met.

• Lucas Prata, last heard on Z-100 in this realm in 2006 came back for another round of “And We Say…Let’s Go Mets,” this time swapping out references to Billy Wagner and Carlos Delgado for “Familia, Clippard, Reed and Robles, too”.

• Maxine Linehan put her beautiful Irish-born vocals to work in tribute to Daniel Murphy, a.k.a. “Oh, Danny Boy!”

Also worth a nod from non-traditional channels: Jim Breuer, whose SNL and standup fame provided him a platform to serve as Celebrity Mets Fan of the People via the videos he’d upload to Facebook after virtually every game in 2015. Breuer exulted and occasionally mourned, more or less like any of us. A happening was born.

And as if all that’s not enough (as reported by sharp-eyed FAFIF readers and other concerned parties or tracked by yours truly)…

In 2015, the real Ed Charles made two particularly memorable appearances, in January at the Queens Baseball Convention and in October throwing out a first pitch alongside teammate Ron Swoboda during the NLDS. Just two years earlier (and continually on HB0 since), he was revealed, at the end of 42, as the little boy who caught a ball from Jackie Robinson in Spring Training. As the postscript to the movie read, “Ed Charles grew up to become a Major League Baseball player. He won the World Series with the 1969 Miracle Mets.”

The Stargate TV followup, Stargate: SG-1, showed pictures of Jack’s son in a Mets uniform.

Peter Falk as Vince Ricardo in The In-Laws (1979) while on a stakeout: “I can’t believe this trade. What the hell the Mets need another pitcher for? All they got is pitchers!”

Jeff in Rules of Engagement (which ran on CBS between 2007 and 2013) mentioned the Mets frequently and loved to show off his Mets memorabilia collection at any given opportunity.

The Gift of Life, by Michael Elias (2013), discusses the Mets and features the main character’s connection to them. Specifically, the narratives in the book refer to the dominance over the Mets by the Braves, the exciting 2006 season and ultimately short-circuited postseason (including a dramatic retelling of the late stages of the final playoff game), the 2007 collapse, and other baseball commentary as observed by the main character. The novel, according to the author, is “about so much more than that, including disability and coming to terms with certain life situations, but there’s the sports aspect of it for fans as well”.

“Legal or not, if it gets the New York Mets a better shortstop, I am so down with this,” said team minority owner and talk show host Bill Maher regarding the opening of US-Cuba relations (Real Time, 1/16/2015).

In the Rex Stout Nero Wolfe novels from 1962 on, Archie Goodwin is a diehard Mets fan (and a former New York Giants fan).

“I Didn’t Always,” a 2015 song by Andee Joyce, includes the lyric, “the monster is out of the cage”.

“Replacement Baseball,” a Ken Burns film parody on Saturday Night Live, April 15, 1995, uses a wide shot of action at Shea; also a picture of Nolan Ryan pitching for the Astros at Shea. The threat of actual replacement baseball was real that spring because of the strike that wouldn’t end, which was reflected on SNL’s September 24, 1994, episode, in which there was a commercial for Super Sports Tours’ 1994 Baseball Strike cruise, wherein one of the players featured as appearing is “Mets All-Star slugger Bobby Bonilla”. The gag was basically every striking ballplayer will be on the ship. At the end of the filmed bit, several MLB players are on stage, including Bonilla, in his 1992 road jersey and cap.

Married With Children, “A Man For No Seasons,” November 27, 1994, features a passel of striking players, including then-Met Bret Saberhagen appearing as himself, forced to get a job as a pizza delivery man, of which he says, “I’ve got the worst job in the world.” When Kelly Bundy notices his nametag says “Bobby Bonilla,” Saberhagen explains, “He called in sick.” Also, “If I don’t deliver this pizza in thirty minutes, they take it out of my check.”

Reportedly, a cop in the 2014 Off-Broadway play, “Between Riverside and Crazy,” decides to become a Mets fan because he hates Rudy Giuliani.

Harry Breitner’s well-titled 2014 song, “Faith and Fear in Flushing Meadows,” references 1962 (and losing), Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Ray Knight, Mookie Wilson.

In the pilot episode for the latest iteration of The Odd Couple, starring Matthew Perry as Oscar Madison, February 19, 2015, Oscar is a sports talk radio host who, in the opening, is taking a call from someone who can’t believe Oscar things the Mets have a shot this year. Oscar hangs up on him. Oscar wears two Mets t-shirts in the episode and his apartment is prominently littered with Metsiana and other sports stuff until Felix (Thomas Lennon) moves in and cleans up.

“You’re right, Father. I’m a Mets fan now.”

—Danny Castellano, The Mindy Project, after his priest (guest star Stephen Colbert) tells him the Yankees are “the team of sin,” March 10, 2015, S3, Ep 19, “Confessions of a Catho-holic”.

The Dark Knight had a predecessor in Mets lore. On June 25, 1966, a live “Batman Concert,” featuring Adam West and Frank Gorshin (as the Riddler), took place at Shea Stadium. The Mets bore the brunt of several jokes, including, “Why are the Mets like my mother-in-law’s biscuits? … Because they need a better batter!” and “The Mets are like a box of Kleenex, because when they get boxed in, they pop out one at a time!” The conceit was Batman had come to Shea to save the Mets (the original script called for Mayor Lindsay’s participation; the mayor was supposed to have expressed concern over “the trouble the New York Mets have been having,” and thus called for Batman’s aid). The event, whose original bill included acts like the Young Rascals, the Chiffons and the Temptations, drew 3,000 young people to the ballpark. That same Saturday in Chicago, the Mets were beating the Cubs, 9-3, behind a complete game 11-hitter from Bob Shaw and home runs from Ed Kranepool and Eddie Bressoud.

Probably not heard at Shea on Batman’s big day was a song recorded in 1966 by Ray Watt & The Questions. It was called “Till The Mets Win The Pennant,” and was released on LOY Records, a label out of Winchester, Ky. The lyrics are light on baseball, focusing on love and longing. The Mets are merely a Met-aphor for endless waiting. No way the composer guessed his concept of eternal love would add up to three years’ time in real life.

3-2-1 Contact opened its first episode, in 1980, with a description of all the things its hosts had tried, including Marc (Leon W. Grant) asking, “What about the time I played baseball with the New York Mets?” Roy Lee Jackson is seen pitching to him at Shea, most likely in 1979.

In the music video for “Paging Hiawatha” by the Knockout Drops (2010), the Mets bullpen cart appears driving down a two-lane road.

“In the late ’70s and early ’80s, John Travolta was Scientology’s biggest star,” said the narrator of Going Clear, HBO’s 2015 Scientology documentary. While that was being said, we see Travolta in a still photo in which he wears a 1986-era Mets Starter jacket (a period photo, not a retro item). Meanwhile, footage of 1986 ticker-tape parade shows up in a montage scored to “New York New York” toward the close of HBO’s 2015 Sinatra documentary.

On the pilot episode of the Ridgewood, Queens-set Weird Loners, which aired on Fox on March 31, 2015, we meet Eric Lewandoski (Nathan Torrence), 34, toll collector and one of the four title characters. He is wearing a Mets baseball shirt featuring a skyline logo and watches a game with his dad (wearing a 2013-14 style alternate cap). In their game, an announcer says it’s the bottom of the ninth and Wright is up. Father and son argue over whether a base on balls would be an acceptable outcome. Then the pop drops dead. Eric is concerned until he hears the announcer say the batter swings. He turns toward the television and…SCENE. (The episode also includes an appearance by a dermatologist named Howard Blatt, same name as a Daily News sportswriter who once covered the Mets.) In the second episode, Eric watches a Mets doubleheader with neighbor Zara, sitting in for his late father. They both wear Mets jerseys. Hers is a SEAVER 41 blue pullover of the 1983 variety. The Mets lost the first game; we don’t see the second game.

Minor character, major fandom: Ed on Mad Men tips his own Mets cap in 2015 by way of fictional 1970. In Mad Men’s second half of the seventh season premiere (S. 7 E. 8), April 6, 2015, Joan Harris is seen reading the May 1970 issue of McCall’s, with Tom and Nancy Seaver on the cover. Meanwhile, in Ed Gifford’s final scene on Mad Men (“Lost Horizon,” Season 7, Episode 12, May 3, 2015; takes place late summer 1970), the copywriter dons a Mets cap before taking leave of the almost abandoned offices of Sterling Cooper & Partners. And good old Don Draper kept Lane Pryce’s Mets pennant hanging in his office in the “The Forecast,” Season 7, Episode 10, 4/20/2015.

In episode seven of Daredevil…

MATT, discussing Foggy’s injured side: “I think Foggy will be pitching for the Mets by midseason”

KAREN: “I’m being serious”

MATT: “So am I. Have you seen their bullpen?”

The rose ceremony on 6/15/2005 edition of The Bachelorette takes place on the field at Citi Field. The cocktail party takes place in “one of the many luxurious event spaces”.

In Superboy #24, December 2013: “He had the power to read. To influence. At first he was weak and could only affect small minds — like animals and Mets fans.” DC Comics is said to take shots at the Mets since Marvel Comics is generally pro-Mets. Then again, the New York Mehs are portrayed in Superior Foes of Spider-Man and Deadpool, Marvel Comics, 2015

In 1985, Starchild recorded the hip hop ditty “You’ve Gotta Believe (Let’s Go Mets)” on the Fever Records label. Among those listed as producer [original tracks] are Kurtis Blow and Russell Simmons. Lyrics shout out Nelson Doubleday and Frank Cashen, among others, and invoke the signature call of Warner Wolf.

A “Go Mets” message appears on a book shelf in the 2015 season premiere of Teen Wolf. Star Dylan O’Brien is a big Mets fan.

Colin Quinn, as Amy Schumer’s father in Trainwreck, plays a major Mets fan. There’s a 2013 All-Star Game blanket in his nursing home room, a Mr. Met poster torn up by his daughter in anger, Mets apparel in evidence everywhere and, ultimately, a Mets floral arrangement at his funeral.

“Right now, your case is weaker than the Mets bullpen.” So it was said on Blue Bloods, CBS, October 8, 2010, Season 1, Episode 3, “Privilege”. Fast forward to the Season 6 episode “All the News That’s Fit to Click,” October 9, 2015, and you’d find Citi Field serving as a backdrop.

Marc Black offered a folksy number in 2015 called “You Gotta Believe…Mets!” in conjunction with John Sebastian, Eric Weissberg and the sampled voice of Steve Somers.

“I almost moved to the Mets.”

—Moose Washburn, “You Can Win ’Em All,” The Bob Newhart Show, Season 1, Episode 22, first aired February 24, 1973. The line was uttered by .183-hitting Cubs backup catcher Moose Washburn (Vern Rowe), who becomes a patient of Dr. Hartley’s when he sees how Bob has helped his teammate, pitcher Phil Bender. It refers to the many times he’s been traded. He eventually goes to Japan.