The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 May 2015 1:03 pm “I hit behind Yogi in one ballgame […] somebody threw him a fastball up in his eyes and Yogi banged it up the middle for a single and I was sitting there on deck going, ‘This is not a game for which I’m familiar…good god.’ To bat behind Yogi Berra, that was awesome.”

—Ron Swoboda

It wasn’t Gary Kroll’s day. Facing the Reds at Crosley Field on Saturday, May 1, 1965, he was touched for a home run in the second by Leo Cardenas and then roughed up in the fourth: an RBI double to Pete Rose, a three-run homer to Vada Pinson and another he left on base that came around to score after he was pulled. The Mets trailed 6-1 in the fourth.

Casey Stengel would be using his bullpen plenty. Al Jackson finished out the fourth. Larry Bearnarth took the fifth (and was tagged for two more runs). Jim Bethke, at 18 the youngest pitcher the Mets would ever use, held the fort in the sixth and seventh, but as was usually the case, circa 1965, there wasn’t all that much fort to hold. It was 8-2, Cincinnati. Bethke had done nice work, but after throwing two innings the night before and two innings here today, there was the matter of his young right arm to consider. When his turn came up in the top of the eighth — Joe Christopher on first, two out — Stengel called on a pinch-hitter.

He called on Yogi Berra.

Berra was hired to coach, a personnel matter that was considered a publicity coup. He was Yogi Berra. He needed no introduction, not after 18 seasons playing with New York’s American League franchise, picking up along the way world championships, All-Star appearances and MVP awards the way other catchers picked up passed balls. Yogi was so highly thought of that his previous employer chose him as its manager in 1964.

All Berra did in that role was lead them to another pennant and the seventh game of the World Series. Yet he was dismissed. Stengel — who had managed the man with great delight for a dozen seasons— was happy to snatch him up. The whole transaction couldn’t help but make the Mets look good. The Mets had Casey and Yogi. The Mets had the most quotable, most lovable brain trust imaginable.

They didn’t necessarily plan to have an extra catcher. Yogi finished playing in 1963, but these were the Mets, who could always use another catcher. They could always use another anything, really, but having in their infancy and toddlerhood sifted through the Choo Choo Colemans and the Chris Cannizzaros; the Hobie Landriths and the Harry Chitis; the Hawk Taylors and the Sammy Taylors — to say nothing of assorted Joe Pignatanos, Joe Ginsbergs and Jesse Gonders — the Mets behind the plate were where the Rolling Stones were about to be on the radio that summer.

In a perpetual state of dissatisfaction.

So Yogi, at 39 years, 11 months and 19 days of age, consented to be activated. And on this Saturday afternoon in Southern Ohio, he officially became the 94th Met in team history. Berra stepped in against Sammy Ellis and proceeded to ground to first base. Gordy Coleman handled the ball cleanly and stepped on the bag, three-unassisted.

The Mets went on to lose, 9-2. Berra got into three more games over the next eight days — catching twice and pinch-hitting once — before re-retiring, this time for good. He was granted his release as a player on May 11 and resumed coaching full-time. The next day, while holding down the first base box, he celebrated his 40th birthday.

That was May 12, 1965, exactly fifty years ago. That means Yogi Berra has just turned 90 — or the rough equivalent of five ’65 Bethkes. Having participated in that game at Crosley Field made him a Met, and having made it this far means he is the first Met to have ever reached a 90th birthday. Only three Mets (Warren Spahn, Gene Woodling and Gil Hodges) were born before him. None has lasted as long as him.

Coincidentally, Yogi’s Mets playing debut came exactly 900 Mets ago, chronologically speaking. Johnny Monell, also a catcher by trade, pinch-hit this past Saturday night and became Met No. 994 in the annals. Tonight we are slated to be formally introduced to Met No. 995, a young feller by the name of Noah Syndergaard, born August 29, 1992. To date, only one Met (Dilson Herrera) has been born after him. It remains to see how long Noah lasts. We hope his overall run unfurls as lengthily and successfully as Yogi’s in and out of the game.

Though, let’s face it, that’s a pretty high standard.

Yogi Berra was one of the greatest catchers ever, and by dint of that brief 1965 stint, forever holds the honor of first Met player inducted into the Hall of Fame. Richie Ashburn, Duke Snider and Spahn each debuted as Mets before Berra, but Yogi got his Cooperstown call first. We’d love to tell you that it was Yogi’s two hits in nine Met at-bats that sealed the deal, or that his plaque lovingly details the events of May 4, 1965, when he caught Al Jackson’s 11-strikeout complete game victory over the Phillies at Shea — or even that what ultimately won him election in January 1972 was the fine job he had done coaching first base for Stengel, Wes Westrum, Salty Parker and Hodges — but we can’t. Yogi Berra had ascended to the cusp of baseball immortality before he ever played for the Mets.

But he did play for the Mets, and no one who can say that has lived a life quite so long.

(Good thoughts at this time as well to Berra’s batterymate Jackson, truly a Met for all ages.)

by Jason Fry on 12 May 2015 1:04 am Hang with ’em.

It was one of the first bits of baseball advice I gave Joshua to pass along to the little figures on the TV who can’t hear us. Blasted a ball up the gap that the right fielder barely speared at a dead run? Hang with ’em. Laser beam perfectly intersected by the apex of the shortstop’s leap? Hang with ’em. Shot right up the middle that vanished into the pitcher’s mitt like a magic trick, leaving the batter out before he even drops his lumber? Hang with ’em.

Things will even out. Good execution, poor results. The worm will turn.

One reason baseball is so full of cliches is that it’s maddeningly fickle — an unfair game, as Rod Kanehl sagely noted once upon a time. Poor preparation and awareness may be rewarded; Herculean efforts and perfect approaches may be punished. There is no defense against this perversity except a dogged belief that the baseball universe bends towards … well, not justice exactly, but a cosmic evening out. Cliches are comfort, the only part of the sport that can be made predictable and orderly.

Tonight’s game, in a half-reconfigured Wrigley Field with the wind blowing out, was actually kind of fun — well, in theory. Jacob deGrom is experiencing growing pains, trying to navigate poor location with his fastball and an apparent lack of confidence in his offspeed pitches. The Cubs leapt on him early, with Kris Bryant hitting his first hometown homer on the first night the left-field bleachers had been reoccupied. Bryant’s Wrigley Field homers will soon become a blur of bad news for visiting teams, but this one was special even without the theater — I was standing in the kitchen and my head jerked up at the sound of bat hitting ball. It was a sound Buck O’Neil would have appreciated, the sound of the hardest thing to do in sports done perfectly. With the crowd still buzzing about Bryant’s heroics, the rapidly maturing Anthony Rizzo then demolished another baseball, sending this one into the yet-to-be-reoccupied right-field bleachers.

DeGrom looked like he’d soon be watching the rest from a dugout slouch, but he managed to hang around and Terry Collins seemed determined to make the game a learning experience for him. DeGrom nearly crumbled in the fourth, but erased Rizzo on a two-out, bases-loaded grounder. Meanwhile, the Mets had stopped fishing so avidly for Lester’s slider and curve and started seeking aid from Andy Fletcher’s strike zone, which was both undersized and given to butterfly-like wanderings. Lucas Duda and Wilmer Flores went back to back themselves in the sixth, and somehow the Mets were within one with Dilson Herrera on second, Ruben Tejada called on to pinch-hit, and Lester fighting a losing battle against the urge to rush home plate and body-slam Fletcher. Tejada was called out on a pitch that looked low, which seemed like an injustice until you thought about all the other pitches Mets hadn’t been called out on that looked perfectly fine.

Still, the Mets were down by a skinny run with a better bullpen than the Cubs and nine outs to play with. Which seemed doable. Too bad the Big Hang With ‘Em was soon to begin.

In the eighth, Michael Cuddyer led off with a single and Duda absolutely vaporized a ball down the right-field line. It was headed into the corner, or possibly through the brick wall and into a nearby bar, or possibly it would carve a smoking tunnel through the Earth and emerge somewhere in Michigan. Unless, of course, it crashed straight into Rizzo’s glove, allowing him to double up Cuddyer.

Ugh. Hang with ’em, Lucas.

Were we done? Not hardly. Curtis Granderson worked a walk to start the ninth, bringing up Herrera — who smoked a ball to the left of second base. Despite being the apple of our off-season eye, Starlin Castro hasn’t exactly been the anti-Flores at short so far, and this ball was past him. Somehow Castro corralled it to force Granderson at second.

Ugh. Hang with ’em, Dilson.

Johnny Monell was our last chance, and he smacked a hard grounder — right, inevitably, at Addison Russell. Russell surrounded it, started the double play, and we were done.

During my postgame sulking, I saw this from MetsProspectHub: The Mets are 5th in line-drive percentage at 22.6% and 21st in BABIP (batting average on balls in play) at .281. As MPH put it, “they haven’t just been unlucky. They’ve been STUPIDLY unlucky.”

Or as I’d put it, hang with ’em.

by Jason Fry on 11 May 2015 2:43 am Any baseball game is a good one, of course, but the Mets played a fun one against the Phils on Sunday — you had some exciting home runs and other big hits, good starting pitching, some nifty plays in the field, and drama. Though not too much drama. You also had contributions from people you expected and ones you didn’t. Which was a useful reminder that teams with October aspirations get there by relying on a lot more than eight members of the starting lineup and five starting pitchers. They need a lot more than 25 guys, even — you’ll need noteworthy performances from momentary relievers, infield fill-ins, third catchers, spot starters and more. Here’s a roll call for Sunday’s game, from the expected to the less so:

Bartolo Colon: The big man, noted at 210 by an apparently straight-faced Ron Darling before game time, wasn’t masterful but was his usual fuss-free self, fanning six to move to 6-1 on the season. (Less amusing: His inability to get a bunt down in the fifth with the Mets down 2-1.) But still: Bartolo Colon has walked one guy in 2015. One! And to think a lot of us were bemoaning that second year of his contract.

Curtis Granderson: Colon’s failure bunting didn’t matter thanks to Granderson, who hit a laser-beam home run off fellow base-trotter Chad Billingsley to put the Mets back up 3-2. I’ll take more of that, please.

Kirk Nieuwenhuis: It hasn’t been a season to remember for Kirk, who shaved off baseball’s best beard and then had to confront an unhirsute batting average. But Nieuwenhuis got it done Sunday, with an RBI double, an alert steal of third that became a run when Darrin Rupp threw the ball down the line, and a skidding catch in foul territory for the final at-bat of the game. He also allowed the Phils a potentially critical free base with an ill-advised throw home, but on balance it was a good day for a player who needed a good day really badly.

Johnny Monell: Spring training’s star began his Mets career with a good at-bat Saturday, then collected his first hit today with an eighth-inning double off Jeanmar Gomez, one of those balls in the gap that seems to speed up once it hits grass. Doubles for your side are by definition good things, but this one was critical, bringing in Anthony Recker and Ruben Tejada to turn a 5-4 Mets lead into something more comfortably Colonesque. And when was the last time you saw one backup catcher drive in another backup catcher? Get Elias on the phone!

Ruben Tejada: Man, dude has more lives than a whole litter of cats. On Saturday night Tejada saved the Mets from disaster in the eighth with a backhand stab in the hole, then coolly got his bearings for a quick flip to Dilson Herrera and an amazingly welcome 6-4-3 double play. On Sunday, Jeurys Familia began the ninth inning by allowing a single to Carlos Hernandez. A fielder’s choice replaced Hernandez with Carlos Ruiz, but then Ben Revere hit a Baltimore chop to the lip of the infield at second. That threatened to bring Freddy Galvis to the plate as the tying run, but Tejada somehow used his glove like a Ping-Pong paddle, goosing it to Duda for the out. The play looked like an optical illusion — the ball barely registered as in Tejada’s glove at all.

Ryan Howard: No, this doesn’t say Alex Torres, because the smaller, beturbaned member of the Torri is a hot mess right now, unable to locate the plate. After Saturday night’s horrifying walkfest, Terry Collins went back to Torres in the eighth with one out and the tying run on second. Torres immediately walked Revere, which is basically impossible. He retired Galvis, but his pitches kept sailing inside to left-handed hitters, and he hit Chase Utley to load the bases. That brought up Ryan Howard, and surely Collins would remove Torres and go to Sean Gilmartin. Nope; Terry stuck with Torres and his suddenly theoretical grasp of the strike zone. So Howard, a 12-year veteran, inexplicably swung at the first pitch, grounding out to Duda and short-circuiting the Phils’ chances for the day. Amazing.

Angel Hernandez: Every Mets fan’s favorite umpire made his presence known early, ruling Revere safe on the first play in the bottom of the first. Um, no. Replay showed Angel was wrong, which was doubly delicious for Mets fans. If Major League Baseball would like to improve the world’s greatest sport, it could do so very quickly by throwing Angel Hernandez into a pit of wolves telling Angel Hernandez to find another line of work. Failing that, at least we have replay — though Angel, rather memorably, turned to replay and still managed to screw up a home-run call in Cleveland two years ago, boning the A’s out of a ninth-inning tie. If that seems impossible, well, like so much else about this game Angel Hernandez is amazing in his own way.

by Greg Prince on 10 May 2015 10:58 am Many of you will probably tire of seeing it before long, but for those of you not in the New York market, we’ve obtained the script for the “Niese On Nissan” commercial that will be airing incessantly during Mets games for the next several months. The ad was shot late Saturday night outside Citizens Bank Park after the Mets’ 3-2 win over Philadelphia.

[METS MANAGER TERRY COLLINS AND METS BENCH COACH BOB GEREN STAND BY THE ENTRANCE TO THE TEAM BUS, EACH WITH A CLIPBOARD.]

COLLINS: All right, Bob, now that the game is over and we’ve won, we have to make sure everybody’s on the bus.

GEREN: You’ve got it, Terry.

COLLINS: Lagares!

GEREN: Juan had to run a long way, but Lagares…on the bus.

COLLINS: Carlyle!

GEREN: Buddy was just having a catch with some kid, but Carlyle…on the bus.

COLLINS: Monell!

GEREN: Johnny was wondering when you’d call for him. Monell…on the bus.

COLLINS: Gee!

GEREN: Uh, Terry…

COLLINS: Oh, right. Syndergaard!

GEREN: Wow, if Noah throws as fast as he just raced to get here, he’ll be doing all right. Syndergaard…on the bus.

COLLINS: Tejada!

GEREN: Tejada?

COLLINS: Where the stinkin’ heck is Tejada?

TEJADA: I’m comin’, skip, I’m comin’.

COLLINS: Ruben, I thought we talked about you bein’ stinkin’ late even when you’re on time.

TEJADA: No, skip. I’m just bringin’ my double play partner along.

COLLINS: What the…?

GEREN: Ruben’s right, Terry. Tejada looks much better when he’s paired up with Herrera.

COLLINS: I don’t give a stinkin’ darn how they get on the bus as long as they’re on the bus.

GEREN: Tejada, Herrera — and Duda…on the bus.

COLLINS: Niese!

GEREN: Jon?

COLLINS: Niese!

GEREN: Jon!

COLLINS: NIESE!!!

GEREN: Gosh, Terry, I don’t see Jon anywhere.

COLLINS: That’s stinkin’ ridiculous! Everybody gets on the stinkin’ team bus after the game! Everybody but Harvey, but he’s Harvey. Niese ain’t Harvey. The team bus is sittin’ right here and I want NIESE ON!

[METS PITCHER JON NIESE DRIVES UP TO WHERE COLLINS AND GEREN ARE STANDING.]

NIESE: Did somebody say NIESE ON? Or did they say NISSAN?

COLLINS: Niese! What’s the big idea?

NIESE: The big idea, skip, is you’re not gonna have NIESE ON the bus anymore, because I’ve got the brand new for 2015 NISSAN ALTIMA. Or should I say NIESE ON ALTIMA?

COLLINS: What? Who said Niese is the ultimate?

NIESE: Well, skip, now that you mention it, when you’ve got a pitcher who can give you seven solid innings and get the leadoff hit that starts the winning rally, you may have the ultimate.

COLLINS: Don’t get carried away, hot shot. It was the Phillies you were holdin’ to one run and I didn’t pinch-hit for you because, if you haven’t noticed, I don’t carry any bench players.

NIESE: Relax, skip. Feel the smooth ride, like the one I’ve been giving you almost every fifth day. And there’s plenty of trunk space for me to carry most anything, including our tepid offense.

COLLINS: I’d like to see how it responds when you hit bumps in the road the way you usually do.

NIESE: Nah, not me, skip. I’m totally relaxed behind the wheel of the Nissan Altima, which is built to take on the toughest city traffic.

COLLINS: Even when we’re goin’ to Washington? Because that’s usually a bad trip.

NIESE: Skip, with fluid, powerful acceleration, refined handling, and an incredibly efficient fuel economy, there’s nothing the Nissan Altima can’t do.

COLLINS: Sounds like you’re describin’ your pitchin’ tonight.

NIESE: Thanks skip!

GEREN: Hey, lovebirds, everybody else is on the bus. What about you two?

COLLINS: You take the team, Bob. I’m hitchin’ a ride with Jon here. Because when we’ve got NIESE ON, we’re goin’ stinkin’ places!

NIESE: Listen skip, I do think you take me out too early too often.

COLLINS: That reminds me — where’s the hands-free phone in this thing? I’m callin’ the bullpen to get Torres up as a relief driver.

NIESE: Torres? Again?

COLLINS: Calm down, cowboy. I didn’t say which one.

NIESE: It’s Carlos, isn’t it?

COLLINS [TO CAMERA]: This guy.

NIESE [TO CAMERA]: This car!

COLLINS & NIESE [TOGETHER TO CAMERA]: What a ride!

by Greg Prince on 9 May 2015 9:14 am When you’re sending your ace of aces out to face the dregs of the dregs, you can’t help but have high hopes…high in the sky apple pie hopes. In this corner, we had the undefeated Matt Harvey, author of the best day (sometimes two days) of every week. In the other corner, there sat the oft-defeated Philadelphia Phillies, who — an inside pitch or two notwithstanding — had barely laid a glove on our heavyweight champ in any of their previous meetings, dating back to 2012.

It looked good going into Friday night at Citizens Bank Park.

So good.

Too good.

Mortal Matt wound up no match for the fickle fates and lost to the remnants of the once-mighty Pennsylvania Proprietors of the National League East. Up from their basement apartment rose Ryan Howard (a homer and two ribbies), Cole Hamels (seven easy innings) and Jonathan Papelbon (who wasn’t a Phillie until they started falling apart yet is now somehow their all-time co-leader in saves; go figure). Freddie Galvis cranked his batting average above .350, Chase Utley took his below .100 and, most relevantly, Matt Harvey saw his mark drop to 5-1.

Oops, there went another Harvey Day start, kerplop.

As Monty Python taught us, every Harvey Day is sacred, so it’s a shame to let one go for naught, especially in foul, fetid, fuming, foggy, filthy Philadelphia. Matt threw a quality start in the most minimalist sense (6 IP, 3 ER), but the other guy happened to be that thing where you’re not worse and you’re not the same but you’re…you’re…

I can’t bring myself to admit anybody could be better than Harvey, particularly Hamels, but yeah, something like that. It would have helped had the Mets hitters brought their bats on the trip, but perhaps they’ll arrive in time for tonight’s game.

On one hand, it’s always nice to be reminded of the presence of several relief pitchers whose existence you’d pretty much blanked on. Hansel Robles, it can now be confirmed, is still alive. On the other hand, the 3-1 loss left the Mets’ record at 18-11, which appears exceedingly healthy to the moderately trained let alone perfectly sane eye, yet stares back at me hauntingly through the prism of 2002, when the first-place Mets were 18-11 after 29 games, with Pedro Astacio moving to a Harveyesque 5-1 the night they reached that plateau. Yet it was all downhill from there for the next five months (57-75), then further downhill (137-186) for the next two seasons.

In a similarly pre-emptive gloomy vein, because that’s how I roll when Matt Harvey doesn’t win and Matt Harvey’s teammates don’t hit, Bryce Harper socked another couple of home runs down in Washington last night, as the Nats whittled the Mets’ first-place lead to a precarious 3½ games (with, granted, 133 to play). In an eleven-day span, the foul, fetid, fuming, foggy, filthy Federals have picked up 4½ games. So that’s bad news. The Mets not taking full advantage of Harvey’s rotational presence is bad news. David Wright reporting lower back pain and having his hamstring rehab shut down is bad news.

Then there’s Dillon Gee’s groin, which sounds like it should be a private matter between Dillon and his doctor, but you know how it is with athletes’ body parts. In exchange for extraordinary pay and exclusive perks, we get full access to their medical records. Thus we learned on Friday that good old reliable Dillon’s groin is strained and he has to go on the DL, making way for Noah Syndergaard to take his turn on Tuesday.

Quit smiling. An injury to a Met is never good news. Dillon’s a good guy. He’s one of my favorites on this team. He is to menschen what Harvey is to aces: state-of-the-art. Last Sunday he likely became the first Met in the 54-year history of the franchise to use the word “finagled” in a postgame interview. That may not sound like much, but when a boy from Cleburne, Tex., comes to New York City and takes on the tongue of the natives, it gets you right here.

I’m pointing to my heart, not his groin.

Then again, if you have to reach down to Triple-A and call up another pitcher (another Texan, it so happens), you could do worse than Syndergaard, who ranks somewhere between ninth and eleventh among all prospects in baseball, depending whose forecasts you follow, and has been doing to minor league hitters lately what Harper’s been doing to major league pitchers.

He’s been bleeping owning them.

So yeah, there is a silver lining to the Mets presently having ten players — including eight pitchers — unavailable due to injury/suspension, even with the caveat that chickens absolutely detest getting counted prior to hatching. Still, if you can’t summon an anticipatory froth over seeing the guy you’ve been hearing about for almost two-and-a-half years make his major league debut, then mister, you might need another sport.

Also, Syndergaard can hit, which is no small favor the way this offense is going. Come Tuesday at Wrigley, Terry’s gotta bat him sixth.

Only kidding. He should bat him fifth.

by Greg Prince on 8 May 2015 2:53 pm Not many books draw attention more for their subtitle than their title, but Baseball Maverick’s most striking come-on clearly sits below the marquee:

“How Sandy Alderson Revolutionized Baseball and Revived the Mets”

The unaffiliated reader might arch an eyebrow at the part in which one man is claimed to have transformed an entire sport, but that pales in comparison for shock value to the Mets fan who tried to comprehend, before the 2015 season began, that the Mets had been “revived”. It wasn’t difficult for an army of skeptics to summon contrary evidence.

Alderson took over from Omar Minaya as general manager following the 2010 season. The Mets’ record entering his GM tenure was 79-83. Four seasons later, their record was 79-83, with no higher spikes posted in the intervening years. Baseball revolutions notwithstanding, truth-in-advertising ethics suggested “…and Helped the Mets Hold Serve” might have been a more accurate, if not nearly as provocative, description.

That’s some kind of subtitle. Between the time I picked up Baseball Maverick and the time I finished reading it, author Steve Kettmann (and/or the marketers at Atlantic Monthly Press) emerged as prophetic. The Mets had indeed revived, albeit in a small sample. When they rose to 13-3, I probably would have bought into anything that implied anybody having anything to do with the Mets was a maverick, a revolutionary, a benevolent wizard, what have you.

Things have settled down a bit from the loftiest heights of April, yet you would have to strain your inherent anti-Alderson animus to argue against the concept of a wholesale organizational revival at this moment. The big club is lodged in first place, the Triple-A affiliate has won fourteen in a row and three of the GM’s four top picks to date were, through Wednesday, batting at least .300 in the minors. While a clutch of holdovers from before Alderson’s takeover have played a major role at the major league level, the current team was, for primarily better if occasionally worse, Sandy-crafted.

Is there, then, a straight line to be drawn from the 2015 standings back to what Kettmann wrote? Do we leave his book’s final, post-2014 ruminations convinced Alderson transformed the Mets into something permanently better than they were — something they couldn’t possibly have been without the Maverick’s visionary leadership?

It’s hard to say that every time I watch something go right of late that I think I saw it coming because of a tidbit I read in Baseball Maverick. The book seems to take place in an adjacent if not exactly alternate universe to the one we’re used to seeing the Mets in.

In Baseball Maverick, the defining moment of the Alderson era is the trade of Carlos Beltran for Zack Wheeler, and Wheeler is a central figure in the revival of the Mets. Wheeler, you may have noticed, hasn’t pitched in 2015, when the supposed revival seems to bearing serious fruit. This, of course, could not have been foreseen by the author. Still, the emphasis on young Zack’s rise through the system, complete with recollections of how he preferred to sleep late when he was a Giant farmhand, feels a little off the beaten path, which is a direction Kettmann tends to wander toward a good bit. Besides tracking the ups and downs of Zack Wheeler’s minor league doings, there’s also a surprisingly lengthy visit in the midst of 2013 with Josh Satin, who might have been an engaging fellow but, save for a few hopeful weeks of on-base percentage, never loomed as more than a passing figure on the Met scene.

There are Aldersonian elements behind stressing Wheeler and including Satin. Zack was a big-deal prospect whose debut was hotly anticipated two years ago and he presumably continues to figure prominently in Met plans once he heals from Tommy John surgery. Satin’s plate approach was in line with that which the organization was known for preaching. You can make out what Kettmann is going for in these instances, it’s just that some of his pitches wind up a little off the plate.

Where the book fascinates and excels is in its first third, our introduction to Richard Lynn Alderson. Did you know only Sandy’s wife calls him Rich? Did you know Sandy ran a mild scam while he was in college so he could get into Vietnam? Did you know he was literally the poster boy for the United States Marine Corps? Did you know that his baseball baptism brought him into the crosshairs of one Billy Martin? This would be a spectacular life story to follow if you’d never heard of Sandy Alderson; it’s even better because you keep finding yourself thinking, “This guy? The guy from the Mets?”

Yeah, that guy. Kettmann draws him out and draws him well. Seeing how Sandy became “Sandy” was a treat. Perhaps it’s because of Kettmann’s background as an A’s beat reporter, when the proto-Moneyball Athletics epitomized baseball’s progressive movement, that Oakland Alderson comes across as a guy you really want to hang out with.

Eventually Sandy morphs into the version of himself we recognize in Queens, and the storytelling mission shifts from biography of a person to the instigation of that so-called revival. That’s the point where Baseball Maverick can frustrate the Mets fan reader. Kettmann brings an outsider’s perspective to our folkways, which can be valuable (a fresh set of eyes and all that), but it also gave me the sense that we were being viewed from an anthropologist’s remove.

Some of this results in a slightly hostile undercurrent. I can’t escape the feeling that Kettmann has little use for Mets fans, at least those who didn’t know enough (in his judgment) to sit quietly and wait patiently while the heroic Maverick built them a winner. “It’s very New York to celebrate one’s toughness,” the author writes, “and then mock new ideas and turn out in the end to be a follower. This is part of the charm of New York Sports fans; they grunt and scream and yell, but they also turn on a dime.” The Californian also doesn’t seem high on the traditional New York media, which he quotes for Greek chorus effect when it suits his narrative.

One passage struck me for what it didn’t mention. In a chapter focused on Alderson’s return to Oakland last summer, Kettmann notes Travis d’Arnaud homered against Scott Kazmir at the whatever it’s now called Coliseum. That pitcher-hitter confrontation occurred shortly after the one-decade anniversary of when Kazmir became a red-letter name in Met infamy, thanks to one of Alderson’s predecessors sending Scott packing in 2004. In hands more familiar with Met matters, I imagined a paragraph of background on the significance of the 2014 presence of Kazmir, the onetime prime pitching prospect in the Met scheme of things who had been traded too soon for too little. The surrender of Kazmir accelerated the path to the present Kettmann was exploring: the careless culture represented by the casting off of Kazmir; to the Madoff-fueled phase of Metsdom under Omar; to Sandy being hired to remake the Mets once more. It might have also been worth juxtaposing what Kazmir’s career turned out to be —occasionally very good but also injury-riddled and an illustration that nothing’s guaranteed in the company of surefire young arms — with what Alderson was hoping to derive from Wheeler, Harvey and everybody else.

Instead, Kazmir’s inclusion in the Oakland tableau went unremarked upon, while a couple of tweets from current A’s writers reporting Alderson’s hi’s and how-do-ya-do’s to old Coliseum friends were reprinted in full. It was a reminder that for all the delving into the Mets the author was doing, his background was in Alderson, not the ballclub.

Kettmann made some frankly weird choices along the way. In attempting to explain Mets history for the neophyte, he mined some esoteric detail: the scores of a pair of April 1969 losses to the Pirates; Cleon Jones’s 64 walks that championship season; Dwight Gooden raising his record to 4-0 on the day the Mets won their eleventh straight game in 1986. He mentions by name a buddy he brought to a game shortly after Juan Lagares was promoted, yet all we learn about “Dave” is that he preferred eating his hot dog to paying attention to the rookie center fielder. He goes to the trouble of describing a Las Vegas crowd on the night the Boston Marathon bombing case was cracked as having a “confused, edgy mood to it,” but there’s no payoff, 51s-related or otherwise, to that observation. His description of d’Arnaud’s early-2014 slump — “he’d wince like a guy who had just aggravated a nagging injury and mope on his way to the dugout, all but whistling a tune and crying out, ‘It’s so hard bein’ me!’” — simply overslid the metaphorical bag.

That said, there are a slew of delectable nuggets, gossipy and otherwise, scattered throughout Baseball Maverick. The “90-win” challenge, which was eventually dumped on Alderson’s head as if from an ice bucket, is well-dissected. Terry Collins, we discover, admires the hell out of Art Howe. Kettmann shares his experience as a Rookie of the Year voter and uses it to explain why Jacob deGrom broke through. Framing last year’s Mets as “a time-lapse photograph sequence showing growth in progress” fits perfectly. The last time we see that picture, with the Mets ending last season on a high note, it gives us a glimpse of Alderson processing what he and his lieutenants have wrought. On the final day of 2014, Kettmann finds Alderson (who doesn’t much like to watch a game at a game) in the Citi Field parking lot, listening in his car to a delayed satellite-radio signal when Lucas Duda strikes his 30th homer.

“I heard the roar of the crowd before I actually heard Howie describe the home run,” the GM said. “I knew something good had happened, but didn’t know what.”

I could say the same about Baseball Maverick, a work whose access to Alderson and attendant publicity makes it fairly essential reading for the history-minded Mets fan. Because this franchise’s time-lapse photo still had yet to be delivered from the dark room en route to 2015, it’s difficult to say this book provides the intensely curious reader a foolproof road map for How We Got Here. There are just too many odd little detours to keep the journey straight. But Kettmann built in enough fun pit stops along the way to make the trip legitimately enjoyable and reasonably enlightening.

by Jason Fry on 7 May 2015 12:21 am The Mets won a game tonight that was a little snoozy, frankly.

Jacob deGrom was pretty good, being more inclusive with the change-ups he’d left out of his repertoire in his last two starts. Kevin Plawecki came out during the game’s key at-bat by gigantic Orioles slugger Chris Davis and gave deGrom a little pep talk, after which everything went well. (Though deGrom kept missing his location rather thoroughly.) Dilson Herrera hit a home run. Daniel Murphy, our own Swobodan avatar of chaos, got between a runner and his route back to third base and everyone decided it was fine.

Oh, and Juan Lagares made a nice play in center. But honestly I could have that one on a hotkey.

That was really the entire game. One weird play by Murphy, just enough good hitting, the usual Metsian good starting pitching. Not a lot to wax poetic about, or that we’ll remember very long.

And you know what? That’s just fine.

The Mets 11-game run of glory was exhilarating. Their 3-7 stumble while neither fielding nor hitting baseballs was deflating, to use a word much in the news today. The immediate proximity of these two states was exhausting — and it’s a long season. Too long to spend alternating laughing-gas euphoria and hide-under-the-bed despair. If that keeps up we’ll all look like end-stage Howard Hughes by Independence Day. The Mets 11-game run of glory was exhilarating. Their 3-7 stumble while neither fielding nor hitting baseballs was deflating, to use a word much in the news today. The immediate proximity of these two states was exhausting — and it’s a long season. Too long to spend alternating laughing-gas euphoria and hide-under-the-bed despair. If that keeps up we’ll all look like end-stage Howard Hughes by Independence Day.

An unmemorable 5-1 win? I’m fine with it. Just like I’d be fine with some 3-1, 5-2 and 4-1 snoozers, games you can watch with one eye half-open and a bit of drool on the pillow.

Though if they want to bulldoze the Great Philadelphia Tire Fire this weekend, I’d be fine with that too. Whatever works.

* * *

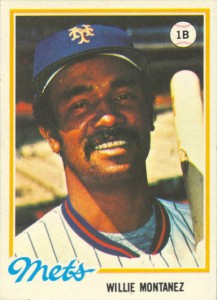

By the way, Willie Montanez got mentioned during Jim Breuer’s entertaining appearance in the booth tonight, which reminded me of the Montanez card I didn’t know existed until a few months ago.

That’s Montanez’s 1978 Topps “Zest” card. What the heck’s a Zest card? Well, in ’78 Topps was trying to market itself to Spanish-speaking baseball fans, and it chose to work with Procter & Gamble with a promotion tied to Zest soap. Send in (to Maple Plain, Minn., inevitably) two labels from Zest bars and an order form and you’d get (in six to eight weeks, inevitably) a pack of five baseball cards. (Here’s a bit more on the set.)

The players were Joaquin Andujar, Bert Campaneris, Manny Mota, Ed Figueroa and Montanez. Other than bilingual backs and different numbers, the cards looked the same as regular ’78s. Well, except Montanez was a newly minted Met. He’d been a Brave in the regular ’78 set, but for Zest he was remade as a Met, with a much better photo. (O-Pee-Chee also had him as a Met, though they kept the Brave photo.)

Great card, ain’t it? I’d go so far as to call it a cardboard classic. Nearly 40 years later, the Zest cards remain both plentiful and pretty cheap. Get yours today! Odds are you won’t even have to send money to Maple Plain or wait six to eight weeks.

by Greg Prince on 6 May 2015 12:40 am What the hell’s so funny about Bartolo Colon? After a year and a month of watching him practically every fifth day, I have to admit I don’t get the joke.

He’s older than everybody. He’s rounder than everybody. He says less than anybody. He swings through almost everything. His batting helmet flies off with little provocation.

Yeah? And?

The Orioles are probably wondering where the absurd aspect of one of the best pitchers in the National League lies. Every time they see him, no matter what jersey he’s wearing, he gives them nothing to grin about. He left them good and grim Tuesday night at Citi Field when he beat them as a Met, just as he has previously defeated them as an Indian, an Angel, both kinds of Sox…basically everything he’s ever been except an Expo.

We tend to laugh with rather than at Bartolo Colon, but we do laugh, probably because he’s so different from his modern pitching contemporaries and we are conditioned to respond to extreme otherness. Somewhere Colon probably chuckles at the fuss he inspires around here. Probably. Maybe. Really, I don’t know. He’s pretty serious where we usually see him, on the mound, busy locating his fastballs, picking up most of what’s hit into his vicinity and generally throwing what he finds where it’s supposed to go (an underrated aspect of his job).

His almost uniformly helpless at-bats I curmudgeonly don’t find as amusing as most do. Bartolo, I’m thinking, you’re not helping my anti-DH argument any. Lightning striking once or twice a generation by way of his bat hitting ball and him hitting the first base bag briefly restores my faith, but it also unleashes a thousand pats on his intermittently helmeted head. I think he deserves better; I think he deserves a little less condescension. If Colon had an ounce of offensive talent, we probably wouldn’t declare international holidays every time he did something at the plate other than draw applause for not falling down (and standing ovations when he comes perilously close to leaving his feet).

Then again, Sandy Koufax famously couldn’t hit water falling out of Fred Wilpon’s rowboat built for two and it wasn’t that big a deal — but they didn’t have GIFs in those days.

I doubt any of it bothers Bartolo. Does Bartolo seem perturbed? Does Bartolo seem anything, come to think of it? It’s all about “seem” since he hasn’t gone out of his way to communicate through translators to reporters to the rest of us what’s on his mind. His teammates swear by him, which is one of those things that usually gets said about guys who don’t say much to the media. Taciturn Eddie Murray’s teammates (save, perhaps, for Eric Hillman) swore by the future Hall of Famer. Bartolo Colon, who has been beating the Orioles so long that the lineups he used to thwart were peppered with ex-teammates of Murray’s, is never referred to as taciturn. He’s not exactly a sphinx, either. He certainly hasn’t gone indefinitely mum as Steve Carlton unappealingly did in his heyday.

Colon simply doesn’t speak for public consumption on any kind of regularly recurring basis. If you want to say he lets his pitching do the talking, then we don’t mind listening. Over 7⅔ innings, here’s what Bart told the O’s: 9 strikeouts, 0 walks, 6 hits, 1 run.

There wasn’t much they could say in return.

The Mets’ offensive juggernaut, meanwhile, revived for exactly one inning, the fourth. It was fueled by Lucas Duda (double), Daniel Murphy (single), Wilmer Flores (double) and Kevin Plawecki (double), allowing it to score three times off Bud Norris. Colon and Jeurys Familia each gave up a solo homer and Juan Lagares gave up nothing, especially ground to Michael Cuddyer, who apparently forgot his job on defense is to not get in the center fielder’s path, even if that path winds toward left. Lagares made a sensational catch, which isn’t news. He avoided getting kicked in the chest by Cuddyer while doing so, which is a relief.

It all added up to a 3-2 Mets victory, an end to the suspicion the Mets would neither score nor win ever again, and a little more to admire about the starting and prevailing pitcher. Bartolo Colon, inching up on 42, has a record of 5-1 and a legend that just won’t quit.

Nothing to laugh at there, but plenty to smile about.

I joined Vinnie and Mike on the Blue and Orange Nation podcast, where the name “Frank Taveras” got itself mentioned pretty quickly. Steal away and listen here.

by Greg Prince on 4 May 2015 3:41 pm Of the 25 fine reasons to read Game Of My Life: New York Mets, perhaps the one that comes out of the farthest reaches of left field is the best. That’s the chapter author Michael Garry devotes to Eric Hillman.

Eric Hillman you probably remember if you were an active Mets fan between 1992 and 1994. The “game of his life” — a Sunday afternoon shutout at Dodger Stadium — you would need a very good reason to specifically recall. But Hillman was a Met for three years when the Mets weren’t very good, he beat L.A. when he was completely on, and thus it makes for an element worth telling within the larger Met story. Hillman is a character worth revisiting, especially when you learn, via Garry’s reporting, what the rest of his life’s been like, particularly a moment when he reconnected with a fan from his playing days.

You don’t have to be a David Wright to have a great Mets story to tell. I won’t tell you what happened, but it’s a beautiful coda to the career of a Met you likely haven’t thought of lately. Game Of My Life has episodes like those sprinkled throughout, catching you up on an eclectic array of 25 Mets who laid down their historical markers between the 1960s and the 2010s. I’m guessing Garry’s publisher probably pushed him to pursue the biggest names possible (in his introduction he describes in detail who he went after and how his success rate varied), but the real treat lies within the chance to check in on Eric Hillman’s good day at Dodger Stadium; Anthony Young before he became known for an almost endless string of losses; Al Jackson, who keeps on instructing Met youngsters more than a half-century after he was one himself; and a few more guys you might or might not expect to read up on in a volume like this.

Garry gives us time with 1969 World Series Game Two hero Ed Charles, who we know never disappoints in his recollections. He drops in on Wally Backman, who takes us back to the day the Mets wouldn’t leave the Astrodome until 16 innings of heartstopping, pulsating baseball resulted in a New York pennant. He provides Bobby Jones an opportunity to piece together his clinching one-hitter from the 2000 NLDS. He shows us that not every “game of my life” is obvious when Daniel Murphy skips the opportunity to emphasize himself and prefers to retrace the final Saturday at Shea, Johan Santana’s breathtaking three-hitter to keep the 2008 Mets mathematically alive, the last time (until now, we hope) Daniel played for a contender. Murph doesn’t know it, but in doing so he echoes Buddy Harrelson, who chooses the day the Mets won it in all against the Orioles as the game of his life, even though Harrelson wasn’t one of the stars of glorious Game Five.

The book hits every era of plenty in Mets history and several of the eras of less-so. Each of the 25 players profiled (most of whom sat and talked to Garry, though a handful of chapters had to be cobbled from outside accounts) is given a respectful hearing and adds something to the overall theme. Our narrator presents himself as a lifelong Mets fan and gives the proceedings a light, loving touch.

We recently spent eleven consecutive games celebrating our ongoing affection for the Mets. Regardless of how often we’ll get to do that on a going basis for the rest of this season, Game Of My Life will give you plenty of cause to celebrate your fandom all over again

by Jason Fry on 4 May 2015 1:35 am My absence from Citi Field has ended. Thirteen months after I was last there, I returned with Emily and Joshua for a game under sparkling skies. We had tacos. We caught up with friends. We ate ice cream (with blue and orange Mets sprinkles). We eyed the new scoreboard and declared it a nice addition, though not one that cried out for multiple press releases. We complained about “Piano Man.” (Sorry, blog partner.) We navigated the new longer lines and seemingly randomly placed metal detectors. (A tip: Use the bullpen gate.) And we cheered for the Mets.

It was a wonderful day … except for whatever those guys in orange and blue down there on the field were doing.

We’re into the second month of the season, which isn’t too early for a scouting report on the 2015 Mets: They’ve got very good pitching, iffy hitting and wretched defense.

Dillon Gee was very good, and the relief corps was terrific, particularly turbaned Alex Torres, who came in with the bases loaded and nobody out and struck out the side.

The hitting, ugh. The Mets put two men on to begin the first and squandered the chance. Then, down 1-0 in the eighth, they were a Lucas Duda fly ball from tying it. Duda fanned on a diving slider that was low and outside. Michael Cuddyer then struck out on a check swing at a slider that hit the ground. Kevin Plawecki‘s double was the lone extra-base hit.

Yet once again, it was the defense that proved the Mets’ undoing by giving the Nationals extra outs. This time the culprit was Ruben Tejada, who botched a transfer on a double-play feed from Dilson Herrera. That led to a Ryan Zimmerman broken-bat parachute that plopped onto the outfield grass behind Duda, and the only run Washington would need.

In other words, it was pretty much a Xerox of Saturday’s game, and about as much fun.

Oh, Ruben Tejada. He made a terrific snag of a ball to his right on Saturday night, but the routine plays have eluded him. Which sounds like I’m describing Wilmer Flores, currently waiting out a head-clearing three-day vacation from shortstop. Except Flores can hit, to the extent that any Met can hit right now. Your answer to “Who the heck can keep us from losing games at shortstop?” appears to be someone not currently on the big-league roster.

That question is taking on increasing urgency. The Mets can’t outhit their own mistakes while missing David Wright and Travis d’Arnaud, absences that have left Duda basically naked in an underwhelming lineup. (I have faith that Cuddyer will hit — he’s done so his whole career — but really wish he’d start proving me right.)

Until Wright and d’Arnaud return, expect more games like today’s — games that will come down to which team converts outs more reliably.

Judging from the last week or so, that’s not a reason for optimism.

|

|

The Mets 11-game run of glory was exhilarating. Their 3-7 stumble while neither fielding nor hitting baseballs was deflating, to use a word much in the news today. The immediate proximity of these two states was exhausting — and it’s a long season. Too long to spend alternating laughing-gas euphoria and hide-under-the-bed despair. If that keeps up we’ll all look like end-stage Howard Hughes by Independence Day.

The Mets 11-game run of glory was exhilarating. Their 3-7 stumble while neither fielding nor hitting baseballs was deflating, to use a word much in the news today. The immediate proximity of these two states was exhausting — and it’s a long season. Too long to spend alternating laughing-gas euphoria and hide-under-the-bed despair. If that keeps up we’ll all look like end-stage Howard Hughes by Independence Day.