The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 29 January 2013 3:34 am Kudos to the Mets for hearing the voice of the people — with Mets Police as ever flicking on the microphone so that voice could resonate loudly and clearly — and changing Banner Night, which had been Banner Day, back to Banner Day. For those of you who missed it or aren’t immersed in hashtags, the Mets had scheduled Banner Day for a Sunday afternoon in late May. ESPN, as is its wont, printed up a banner that read, essentially, WE DON’T CARE, and plucked that game in particular for a Sunday night cablecast. Banner Night is not unprecedented if you know your Mets history, but it’s not an ideal platform for a promotion just refinding its mojo after an eternity of inactivity.

The Mets’ first reaction to ESPN’s bedsheet bullsheet, judging by their inertia, was no reaction. Then a sizable segment of the fan base that lives on Twitter got energized. That doesn’t always mean anything, as a sizable segment of anybody can be energized over anything on Twitter for five minutes. But this movement had legs. Enough #Mets fans made enough noise that the Mets responded. They came up with three dates (two afternoons and the transplanted night) and polled the delegation on when it wanted to fly its banners. Next thing ya knew, Banner Day was rescheduled to Saturday afternoon, May 11. Personally, I think the second weekend in May is a tad too early in the season for us to know who and what to hail on our placards, but the people spoke, and I say huzzah that we were heard.

All hail Mets democracy! All hail our benevolent management for occasionally putting its customers first! All hail something that works!

Someday, how about hailing the return of the Banner Day Doubleheader?

The Mets did the right thing, but it still isn’t quite right enough for my tastes. I was thrilled to have Banner Day back in 2012 and am glad it maintained its foothold for 2013, yet I don’t believe it will ever flutter in full glory as merely a pregame jaunt. Banner Day before a day game is better than Not Banner Day at all, but not as good as it could be.

Spirit wasn’t missing from the Banner Day celebrants last year. What was AWOL was an audience. Hardly anybody was in the stands at 11:30 in the morning and SNY’s cameras were still in their off position. The Mets’ network of record was busy airing a crucial infomercial, while most of those who held tickets for the Mets-Padres matinee were still getting in their cars or on their trains. I made a point of showing up at Citi Field early and I still missed the initial portion of the procession.

Banner Day is simply more festive when it features more people. People striding with banners. People watching from the stands. People watching from their couches. People already in a Mets lather from having watched one Mets game and preparing to watch another.

Only an act of God or ESPN can create a doubleheader these days, but as noted a couple of years ago in this space, there is modern precedent for reviving a staple from the past. The Oakland A’s received special dispensation from the Players Association to schedule a doubleheader in advance because it seemed novel and likely to attract a crowd (which it did). There’s also the Patriots Day precedent in Boston. There, once a year, they start a game well before noon because it’s their tradition.

Our tradition — a tradition too strong to die, even after sixteen years of dormancy — is Banner Day…the Banner Day Doubleheader. The stuff of legends. The stuff of extra-inning openers that kept the banners rustling in the wings for as long as it took. The stuff that kept Channel 9 must-see TV between games. The stuff that a stadium full of Mets fans stood to applaud when it was done.

The Banner Day Doubleheader: that’s the stuff. It’s good that Banner Day has returned. It will be even better when it’s whole.

Meanwhile, the management of Banner Day Press proudly invites you to march triumphantly to Amazon and order The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), where you can read about classic placard parades and so much more.

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2013 3:04 am Sandy Alderson’s infamous Internet search for outfielders — fictional or otherwise — wouldn’t have turned up the name Ed Bouchee. Bouchee was a first baseman. Besides, the Mets already gave him a shot. He was an Original Met, our very first pinch-hitter. He batted for Roger Craig in the top of the fourth on April 11, 1962, with two out and nobody on as the Mets trailed Stan Musial’s Cardinals, 5-3.

Ed walked. Then he sat, which wasn’t to his liking. Few are the players who prefer bench duty to taking the field, but Ed Bouchee really made an impression as someone who did not accept being passed over with good humor. In Danny Peary’s 1994 oral history on postwar baseball, We Played The Game, Bouchee didn’t shy away from criticizing the legendary Met figures who he believed blocked his path three decades earlier.

Casey Stengel, inventor of the Amazin’ Mets?

“He shouldn’t have been managing that team. He was worthless. Worthless!”

Gil Hodges, with whom Stengel went when healthy enough to go?

“How could he play Gil Hodges, a one-legged first baseman you had to shoot up with Novocaine, just because he had a name in the New York area and would draw people? How can you play a cripple? I was the guy that should’ve been playing first base.”

The New Breed, who embraced the 40-120 Mets of 1962 with minimal qualification and only semi-ironically?

“I’m not even sure the Mets fans were as great as they were cracked up to be. I just remember they liked to boo.”

Forget Chico Escuela. Ed Bouchee wrote the first draft of Bad Stuff ’Bout The Mets. If he’d hung around a little longer, one assumes he would’ve found fault with Mr. Met (“just a ball hog with a big head”). Whatever merit there was in the man’s observations — Casey was not necessarily revered by every single Met; Gil was on the last legs of a brilliant career by the time he arrived at the Polo Grounds; and we Mets fans, no matter how sweet-natured our collective disposition, are inherently incapable of suppressing our more unflattering opinions — it can’t be ignored that Ed Bouchee was a .161 hitter in 50 games as a 1962 Met. Even on the 1962 Mets, that was pretty lousy. No Met position player who got into that many games that year recorded so low an average.

Ed Bouchee died last week at the age of 79, making him the eighth of fourteen Originals from the Mets’ first box score to have passed on. True, he left behind a light statistical legacy and a few sour grapes, but I invoke him here out of a degree of respect. One of the sentiments attributed to him in Peary’s book I still find pretty solid:

“I resented the portrayal of the 1962 Mets as a comedy act.”

Not that Ed — whose uniform, informed sources say, made baseball card history as the first full Mets outfit portrayed by Topps — didn’t think the whole scene “was a circus”. And not that great Met stories didn’t outnumber all Met wins by approximately the same three-to-one ratio by which defeats overwhelmed victories in 1962. But still, nobody in a competitive, professional endeavor wants to be written off as some kind of clown…a reserve clown, at that. More than thirty years after it mattered, Ed Bouchee pictured himself as a good enough player to start on the worst team in baseball history and stuck up for that team as one that deserved to be taken as a reasonably serious enterprise.

Which brings me back to Sandy Alderson at last weekend’s BBWAA dinner, and the zinger he got off at the dual expense of Notre Dame’s Manti Te’o and his own ballclub’s most glaring void:

“A message to Mets fans: There’s been a lot of talk about our outfield. And I want you to know that I’m in serious discussions with several outfielders I met on the Internet. There’s one I really like. He says he played at Stanford.”

Alderson has good writers, bracing self-awareness and, like Bouchee, certainly knows how to make an impression. A week since delivering one of the most talked-about performances at a baseball writers gala since Bobby Thomson and Ralph Branca dueted on “Because Of You,” I find myself dwelling on Sandy’s comedic turn. I’m thinking about Michael Bourn and the value of draft choices as well, but nothing seems to be going on there, so I keep returning to the gag.

If the best free agents are sometimes the ones you don’t sign, perhaps the best lines are sometimes the ones you don’t deliver, no matter how sly they sound in your head. I could’ve done without Alderson’s, even if that puts me in the curmudgeon column and tars me as a bit of a hypocrite. After all, I make fun of the Mets. You make fun of the Mets. We all now and then make fun of the Mets. Our stake in the Mets is emotional. If we as Mets fans don’t laugh, we as Mets fans cry — or perhaps punch something. You know how that goes.

Sandy Alderson’s stake is a little different. He’s general manager of the Mets. He’s also one of the brand’s primary ambassadors, particularly when there is no 2013 won-lost record — or immediate prospective upgrade from 2012’s — to speak for itself. If the Mets are winning, nobody much cares what anybody who works upstairs has to say about anything. It’s when things aren’t so great that words maybe matter a little more. Casey Stengel understood that, even if Ed Bouchee wasn’t interested in his skipper’s never-ending public relations offensive. When he had an epically bad team, Stengel knew enough to draw attention away from his players’ shortcomings. He didn’t pretend he had worldbeaters on his roster, but he knew how to massage his message. He didn’t call them the Amazin’ Mets because they amazed anybody with their skill and success. Yet it clicked. That’s why there wasn’t nearly as much booing as Bouchee might have thought he heard.

A half-century after Casey regularly held court, Sandy got a good, topical laugh at that widely reported dinner. If he had gone out the next day and gotten a good, reliable outfielder for this season, it would have been a true showstopper. Instead, we continue to sit and wait for Terry Collins to sort through Duda, Nieuwenhuis, Baxter, Cowgill and whoever else until further notice. The Mets, who finished tenth in the National League in 1962, finished tenth-worst in the majors in 2012, yet hold no better than the eleventh draft pick for 2013. If they were to sign mixed-bag Bourn — speedy, defensively gifted, strikes out a ton, bears the mark of Boras — the Mets would forfeit their first pick by a quirk of compensatory practices, and being out your first pick when you’re aiming to rebuild is no small setback. Entering a regularly priced 162-game season without one full-time, established outfielder in his prime, however, is no obvious step forward, either.

It’s not an easy call philosophically, let alone financially (for this operation in particular), though between Scott Boras and the vexing tenth/eleventh slot business, the GM indicates Michael Bourn’s probably no closer to playing for the 2013 Mets than is Ed Bouchee. I’m not sure I mind. Alderson has acted consistently in the interests of a future he judges as palpable if not quite ready for prime time. I appreciate that aspect of his act.

As for the jokes, I’d appreciate them more if he could tell them in a context where the audience is laughing with us instead of at us. Just assemble a team worthy of applause. Once we have that, everything’s a lark.

Want real comedy? Check out Faith and Fear’s erstwhile fantasy camp correspondent Jeff Hysen tonight at 8, at Gotham Comedy Club, 208 W. 23rd St., between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. He’s very funny and I’m not at all uptight about it.

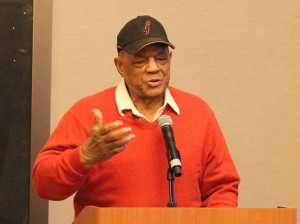

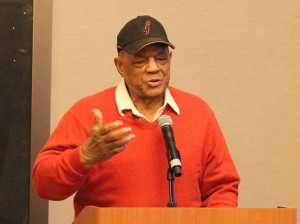

by Greg Prince on 24 January 2013 8:01 am This past Saturday, I sat in the same room as Willie Mays and listened to him reminisce about Leo Durocher and Laraine Day and find a reason to invoke Mel Ott. Bobby Thomson’s name was mentioned prominently by others on hand. Carl Hubbell and Christy Mathewson were namechecked, too.

As Saturdays go, this was a good one to be a New York Giants historical fetishist.

Saying Hey and speaking volumes. These are the sorts of things that will happen when you chase the Giants as I have rather actively for much of this century. You have to keep up the chase, stay on their tail and put up with a whole lot of chatter about a modern-day baseball team whose fortunes are outside your immediate wheelhouse, but once in a while you get very lucky and the New York Giants spring back to life for you. Hell, the greatest of New York Giants walks into your midst and launches into a story about “Leo and Laraine,” and everybody sharing the Saturday with you knows who he means.

Give me one Saturday like that every winter and I’ll make it to spring somehow.

Two of the past three winters have blessed me with such a Saturday, directly coinciding with who won two of the past three Fall Classics. The San Francisco Giants won the World Series. They were awarded a trophy. They had the idea to bring it east with them, ostensibly for the Baseball Writers Association of America dinner and whatever honors they were picking up there. The trophy travels with them as a sparkling conversation piece, speaking with just a trace of its ancestral New York accent.

Naturally, anything that gets Willie talking about Leo and Laraine and 1951 speaks volumes to me.

These Giants are crazy proud of their thirty-flagged bauble, as well they should be. They earned it by sweeping the final seven games they or anybody else played in 2012, and their relatively recent acquisition of a previous prize just like it, in 2010, didn’t dim their appreciation of winning this one the slightest little bit. If they weren’t proud of these trophies, they wouldn’t bubble-wrap them tightly and buy them first-class tickets to fly cross-country so interested parties could admire them.

I guess you could call me an interested party, though my interest in eyeing this latest in a veritable string of San Francisco Giants World Series trophies was cursory, and my interest in being photographed alongside it nonexistent. No offense intended to those who were gracious enough to allow me near enough to it to theoretically say “cheese!” and hold that smile, but I can’t be spending time doing the town with glittering evidence of somebody else’s world championship. Nice way for a Mets fan to turn into a pillar of salt.

But let me not sneeze at that trophy from my team’s vast competitive distance away, for the World Series trophy was my entrée to this very special winter Saturday. It’s how I wound up in the same Manhattan hotel ballroom as Willie Mays. It’s what brought Willie and the Giants to where they both became famous and it’s what allowed me the privilege of being part of the welcoming committee as they returned home.

Well, me and a couple of hundred New Yorkers, including, I’d decipher, a handful of Mets fans whose baseball DNA remains informed by the Giant gene. Mostly it was Giants fans. New York fans of the San Francisco Giants, that is: plenty who were with the Giants when all that took was a ride uptown on the IRT; plenty more who are unbothered that the Giants hopped their last train out of town in 1957, thereby abandoning them in advance.

Funny, they don’t look abandoned.

When I began actively seeking fellow New York Giants enthusiasts with whom to commune in my historical fetishism, I assumed I’d find relatively likeminded individuals. Since I was doing my Giants-chasing in New York, I figured on Mets fans who stared at the orange on our caps and longed to touch the place and time from whence it came. I figured wrong. Oh, there are New York Mets fans who dig on the New York Giants, but the core of the crowd for this sort of meditation is comprised of those who view the current San Francisco residence of the Giants not as a major historical affront, but as, at most, a minor logistical inconvenience.

That was so at odds with my worldview of the post-1957 Giants that I deeply denied its prevalence, even as I’d been encountering it continually for the past nine years, dating back to the steamy July night in 2004 when I trekked to the far West Side to sit in a Verizon warehouse with a half-dozen older gentlemen so I could listen to each tell me what it was like to be a New York Giants fan at the Polo Grounds. Over time and across various venues, the New York Giants talk morphed often into San Francisco Giants talk, as in “Did you stay up to watch the game last night?” When the games last night were World Series games, the New York Giants diminished to a secondary concern at these get-togethers.

Holy Tito Fuentes’s Headband, I thought, the team plays 3,000 miles away under the banner of another city, yet these people are still Giants fans.

Apparently, the Mets fans who dug on the Giants moved on fully to the Mets, pausing now and then to grumble that the Giants are shortchanged in the Mets origin story, but mostly shrugging at that historical omission before returning to snarling at current Met ownership over more pressing missteps. The people who took the legacy of the New York Giants most seriously stayed with the Giants, even if the Giants didn’t stay near them.

Good thing they did, or I wouldn’t wind up in a hotel with the Say Hey Kid, not once but twice in three winters. This, per Lennon and McCartney, happened once before, when the Giants came to our door with their World Series trophy in January of 2011. That was pretty spectacular in its own right, though Willie on that morning kept his Say Heyness rather reined in. Willie seemed tired and reluctant to be adored. When Willie Mays, at his advanced state, doesn’t appear capable of rhetorically running out from underneath his cap, you worry about him a little.

No worries Saturday. I came away from watching him thinking that except for his being 81, I’d take him in center in 2013. Maybe not in center field, but at the center of any baseball convocation.

The Giants brought a trophy. They brought their executive corps. They brought goodwill and World Series press pins and complimentary breakfast. They brought the kind of class a fan dreams his team oozes, championship-caliber or not. But mostly they brought Willie Mays, and Willie works best when he is the main course. In 2011, he shared the spotlight with Buster Posey, and Willie’s self-awareness seemed to tell him to not overwhelm the new kid in town with his own all-time greatness. Willie was Willie, and Willie was the greatest ballplayer ever? Two years ago, many in our ranks couldn’t wait to tell him so. Yet no matter the awe he inspired in men and women of multiple generations, he wanted to make sure we knew how special Buster being Buster was.

His tune hasn’t changed in that regard. The first thing Willie said to us on Saturday after a couple of standing ovations (one just for showing up, the next after he was introduced) was “I didn’t do nothin’” where the 2012 world championship was concerned. “It was the kids,” he said. He meant Posey (who was in town with the Giants for the BBWAA dinner, but not at this event), Sandoval, Zito, Cain, Pagan, Scutaro…all kids relative to Mays. They’re the ones who won the darn thing. Willie Mays knows too much about accomplishing great feats on a ballfield to pretend he should be taking credit for those he had nothin’ do with.

He has plenty of his own anyway. And this year he wasn’t shy about absorbing adoration for any of it. Willie doesn’t actively court worship. He doesn’t have to. But c’mon, he’s Willie Mays. He knows who he is. He knew where he was, too, on Saturday: in the city where it all started for him, from the days when he was the kid, let alone the twilight when he was the wily veteran whose 1973 with the Mets wasn’t altogether dissimilar from his 1951 with the Giants in terms of pennant pressure and fan appreciation. This time, unlike two years earlier, he wasn’t tired. This time he didn’t raise a force field around him to diminish the adoration. This time he was relaxed, engaged…on.

And let’s not forget grateful, which is hilarious, because the gratitude flowed massively from the audience to the featured speaker. We were grateful to be listening to Willie Mays, but Willie Mays was grateful for what New York did for him as a 20-year-old prodigy who was an Alabama babe in the Gotham woods, yet never lacked for mentors at or away from the ballpark. He kept talking about how people in New York “took care of me,” and I got the sense that Willie chatting amiably and answering questions he’s probably answered 24-zillion times was his way of taking care of New York back.

Consider us well taken care of.

Great day to be a New York Giants fan, a San Francisco Giants fan, even a New York Mets fan if you were willing to put aside the continual calls for making these post-World Series celebrations “an annual event” for a team that isn’t the Mets. I’d profusely thanked the fellas who’d connected with the Giants and let them know they still had a Metropolitan Area following — historical and otherwise — but then I felt the need to thank someone with the Giants directly. Thus, I went up to the guy who runs the Giants, Larry Baer, and said:

a) congratulations;

b) thank you for all this;

and

c) I’m a Mets fan who loves the New York Giant roots and I really felt at home here today.

To that, the president and chief executive officer of the World Champion San Francisco Giants made a fist and tapped his heart.

I did mention their organization oozes class, didn’t I?

It wasn’t only a great day to be a San Francisco Giants fan, it’s a great era. They’ve got the World Series trophies. They’ve got the transcontinental lovefest. They’ve got somebody getting up at this thing on Saturday to tell the general manager, Brian Sabean, “you’re a genius” and applause breaking out in assent. That’s what baseball happiness sounds like, I guess.

That goes for Giants fans wherever they’re based. Before Willie spoke, Baer made reference to the Giants being the Giants for 131 years, New York included — “heart and soul” and “heritage” figured prominently in his remarks. Peter Magowan, the man most responsible for keeping the Giants in San Francisco when they were on the verge of vagabonding it to Tampa Bay, described growing up around here: him sneaking a radio into school on October 3, 1951; his dad breaking away from work, going to the winner-take-all match versus the Dodgers beneath Coogan’s Bluff and staying when his companions had given up and left. They were both rewarded with the Shot Heard ’Round the World. The two of them played hooky together the next day to attend the first game of the World Series at Yankee Stadium. Magowan’s message, like Baer’s, was the Giants are the Giants as far as the Giants are concerned, and that designation knows no geographic boundaries.

Willie concurred. “You’re wearing a uniform that says Giants,” he reasoned. “It doesn’t matter where you are.” That (and his lifetime position as special assistant to the president) compelled Willie to declare, “I’ll always be a Giant.” On the other hand, when one audience participant waxed sentimental over his “Say Goodbye to America” speech at Shea Stadium, Willie didn’t renounce his Met detour whatsoever. He even insisted the Mets should’ve beaten the A’s in the ’73 World Series: “We had the better team.”

Two years ago, even though Willie wasn’t all that “on,” my inner ten-year-old did manage to elicit a kindly smile from him when I was granted a sliver of his time, which I used to thank him decades after the fact for his relatively brief Met tenure. No matter whose uniform to whom he pledges eternal allegiance (and he did play in Giant colors for 20 years), he still has a knack for making Mets fans happy…and not just me.

Last April at the Hofstra 50th Anniversary conference, there was a panel discussion on the link between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Mets. One man in the audience stood to ask the panelists why the talk in this realm is usually Dodgers and rarely Giants. I knew instantly this was a kindred spirit, so I introduced myself. The man’s name was Howard, a Giants fan from way back — my kind of Giants fan in that he was sore at the Giants for moving and switched to the Mets once they were invented. I saw him again on Saturday, this time with a program from the 1954 World Series. Howard bought it at Game One at the Polo Grounds and kept score. He showed me the ‘X’ he penciled in to mark the extraordinary putout the home team center fielder made in the eighth inning. You may have seen pictures. The batter was Vic Wertz. The center fielder was Willie Mays. The catch was The Catch.

Howard brought the scorecard to the hotel, and he and his son, Andy, asked someone with the Giants if they could maybe perform a mitzvah before the festivities officially commenced. Sure enough, the scorecard was whisked away and delivered back to its owner a few minutes later…freshly autographed by the center fielder.

“After 55 years,” Andy told me, “my father’s finally forgiven the Giants for leaving New York.”

Immense thanks to Gary Mintz of the New York Giants Preservation Society and Bill Kent of the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society for making Saturday mornings like these possible — and for keeping the New York Giant flame burning so brightly.

You can read about Willie Mays’s greatest moments in a Mets uniform in The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), available via Amazon.

I recently discussed the book in-depth on the appropriately named Happy Recap Radio Show, which you can listen to here. Also, check out Ed Marcus’s thoughtful review of The Happiest Recap at Real Dirty Mets Blog.

Image courtesy of NYBGNS.

by Greg Prince on 20 January 2013 4:03 am Today, baseball mourns the passing and celebrates the life of the original Met-killer — or, more precisely, the Original Mets-killer.

Stan Musial, who died Saturday at 92, raked against the Mets. I don’t think they called it “raking” then, but they could’ve invented the term on the spot once they saw him take the measure of the Metropolitans. He succeeded against all, he flourished against many, but he was the ultimate late re-bloomer when it came to facing Mets pitching.

Musial enjoyed a career renaissance at age 41 in 1962. That was also the year the Mets were born. It did not seem to be a coincidence. On the verge of retirement after turning 40 following the 1961 season, Stan found himself with incentive to keep playing.

“[T]hey invented the Mets,” wrote Jerry Mitchell in The Amazing Mets. “Stan looked at the pitching staff that had been rounded up for the new club and drooled at the thought of the hits he could get if he stayed on; all thoughts of quitting fled his mind. He went right down in the cellar and began to bone his bats.”

A Cardinal spokesman didn’t hide Musial’s expansion glee, either: “[Stan] said something about how nice it would be if he could play 18 games with the Mets, nine of them at the Polo Grounds, which used to be one of his favorite parks.”

Stan Musial’s track record within the city of New York was already the stuff of legend prior to 1962. Nobody’s ever had to listen to Ralph Kiner very long for the story of how Brooklynites, in the course of watching Dodger hurlers surrender 37 home runs to Musial at Ebbets Field, would fret as he left the on-deck circle, “Here comes that man again.” Natch, he became Stan the Man.

The Man hit .359 at Ebbets, but did very well for himself at the Polo Grounds, too, chalking up a .341 average from 1942 through 1957. But when the PG reopened for business in 1962…well, here came that Man again, pounding Met pitchers so powerfully that vibrations could be felt across all five boroughs.

Musial at the Polo Grounds against the Mets in their first year: 11-for-25, with 4 homers (all in one series, including three in the same game) and 10 ribbies. His lifetime average in Manhattan leapt to .345. Overall against the Mets in their first year, The Man was reborn as a kid in his prime: batting .468, slugging .787. The 22-for-47 virtuoso performance, which started with a 3-for-3 on Opening Night in St. Louis and included the first run ever driven in against the Mets, changed the complexion of the National League batting race in 1962. Without his at-bats versus whatever arms the Mets threw at him, Musial was a .314 hitter, plenty solid for a 41-year-old. Mix in what he did to the Mets, the Man was suddenly raking at a .330 clip, third-best in the senior circuit — and incredible, considering his senior status.

Not only did you have to respect him, you couldn’t help but love him. Everything you’re reading and hearing about Stan Musial in death jibes quite accurately with what people thought of him in life, and not just as a revered, retired immortal. The Mets were so enamored of what he meant to baseball (and to New York fans who shared his Polish heritage) after two decades in the game that they honored the Man with Stan Musial Night at the Polo Grounds in August. The Associated Press guessed this was “the first time such an occasion has been arranged for an out-of-town ball player. If it is, it is another of Musial’s growing stack of records.”

Gifts stacked up at Musial’s side when the Mets gave “baseball’s perfect knight” (Ford Frick’s phrase) his own New York night. There were, according to Bill Morales, author of New York Versus New York, 1962, “golf clubs, a hunting gun, and from Ted Williams — his only contemporary peer in the hitting department — a fishing rod.” Representing the New York chapter of the BBWAA, Dick Young presented Musial with a portable typewriter. The press loved him as much as fans home and away, describing him as part of “a vanishing breed…a gentleman professional in and out of uniform”. Musial, in turn, had nothing but good to say about this so-called enemy territory, thanking the sport’s decision-makers for returning baseball to New York, “where I like to play”.

As tipping a cap to a lethal opponent goes, the treatment the Mets gave Musial in 1962 kind of makes that business from last September of slipping Chipper Jones a painting and hoping nobody would notice look even sadder than it actually was.

Yes, different times. And to be fair, if it wasn’t exactly a note of dissent, an element of the Met crowd made an early version of the “not impressed” face at the festivities, at least by the Marv Throneberry-centric reckoning of Jimmy Breslin. “[T]he fans,” Breslin wrote in Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, “proudly wearing their VRAM t-shirts and shouting their cheer, showed much more affection for Throneberry. Musial? He was fine. Great guy, magnificent baseball player. A perfectionist. Only who the hell needed him? The mob yelled for Marvelous Marv.” The Mets’ cult hero’s reaction to the reaction that seemed to favor Marv over the Man?

“I hated to take the play away from Stan on his big day here.”

Not really a problem where Musial versus the Mets was concerned. The Man played on through 1963 and continued to (however gentlemanly) display his own brand of unimpressedness with New York pitching. In two seasons, he came to the plate against the Mets 101 times and reached 52 times via hit or walk. According to ESPN Stats & Info’s Mark Simon, that .515 on-base percentage remains the best any player has ever recorded against the Mets over the course of a career (100 plate-appearance minimum).

It’s always seemed strange to me to realize Stan Musial’s career overlapped with the Mets’ existence. As noted by Morales, he was a contemporary of Ted Williams, not to mention Joe DiMaggio and however many greats one dares inject from that same era into this same conversation. Musial, like Williams and DiMaggio, first played in the big leagues before America entered World War II. He played for St. Louis before Warren Spahn warmed up in Boston, before Ralph Kiner made it to Pittsburgh, before Jackie Robinson debuted in Brooklyn, before Richie Ashburn showed up in Philadelphia. He outlasted all of them, too. Musial was still a Cardinal when youngsters we’d associate with later decades — Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, Pete Rose — were breaking in.

The Mets were a modern creation, yet they crossed paths with Stan Musial at the end of a truly classic tenure. Classic took it to modernity pretty good in those days.

***

And then there’s the “hey guy!” story.

It’s not much of a story, I suppose. It’s been passed along to me second-hand, but ever since I first heard it a few years ago, it never fails to make me want to grab a harmonica and play “Take Me Out To The Ball Game”.

Seems a friend of a friend was in Cooperstown one induction weekend and, since it was Sunday, attended church services. I think that’s how it goes.

OK, so this friend was coming out of church in Cooperstown, and who should come walking in his direction but the great Stan Musial, all 475 home runs and 3,630 base hits of him? It was an awe-striking moment. You go to the Hall of Fame and you find yourself eye-to-eye with one of its prime residents. You couldn’t pray for an encounter like this, but here it is, right in front of you: Stan Musial, ambling right your way.

What in the name of Marty Marion do you to say to Stan Musial? My friend’s friend went for simplicity:

“Hi Stan!”

Stan’s response? He smiled and he said…

“Hey guy!”

…and he continued on his walk.

The Man, indeed.

For a more small-c catholic perspective on Stan Musial, we recommend Joe Posnanski’s reflections, here. And for an array of thoughts on the late Earl Weaver, who managed the Baltimore Orioles to the 1969 American League pennant, Posnanski’s got those, too.

by Greg Prince on 18 January 2013 10:55 am With the Mets acquiring little in the way major league talent this offseason, Sandy Alderson making no promises they’ll acquire any more during what’s left of it and the scheduling of something as ostensibly upbeat as Banner Day/Night somehow managing to piss people off, this correspondent seeks something encouraging or at least intriguing to get him through these final weeks of winter Met malaise.

For that, there’s always Daniel Murphy.

Ah, Murph. Sort of like “Ah, Bach” on M*A*S*H, it doesn’t mean anything, but it sounds like it might. That’s been Daniel Murphy for going on five years now — which in itself is encouraging or at least intriguing.

Daniel Murphy seems almost permanently planted onto our baseball landscape. In an age when players who aren’t David Wright don’t exactly endure on the Mets depth chart, Murphy could practically be said to engender blue-and-orange longevity. How long has Daniel Murphy been a Met?

So long that only Wright and Johan Santana are current Mets who’ve been Mets longer.

So long that he played a significant role on a Met playoff contender.

So long that Daniel Murphy has succeeded, has failed, has persevered and has succeeded again.

But not so long that we’re absolutely sure what Daniel Murphy will be when his final story is told.

In a sense, Daniel Murphy is a throwback, a ’10s version, loosely speaking, of Wayne Garrett: a guy who came up to the Mets as a kid, was in and out of their primary plans, had his ups and downs at different positions, and then — when you were likely thinking about something or somebody else — had suddenly been here forever. Garrett, the only semi-regular third baseman of extended tenure the club could claim across its first two decades, was a Met from 1969 to 1976 and still sits fifteenth on the all-time Mets games-played list with 883 (three more than Keith Hernandez, 44 ahead of Carlos Beltran).

Murphy, despite missing all of 2010 and the last two months of 2011, cracked the Top 50 last year, having now played in 469 games as a Met, or one more than Carlos Delgado and Cliff Floyd. With another healthy year as the regular second baseman, he’s likely to pass Joel Youngblood, Gary Carter and Lenny Dykstra in 2013 and reach No. 35 on the list. Not that there’s any inherent magic in those numbers, but it is an indicator that amid multiple roster reconstructions and a lingering air of clueless mayhem, Murph has truly hung in here as a Met.

It leads me to hope he’ll be around when the Mets turn the same corner they seemed far beyond when he arrived. When Murph made his debut on August 2, 2008, they were fighting the Phillies for first place. Daniel’s blazing bow (.404 after 18 games) was one of the reasons they pushed their way into a division lead within a couple of weeks. The Mets’ reliance on a rookie uncomfortably manning left field — two, counting the starts allotted Nick Evans — may also have been one of the reasons they slipped out of that lead and into a Wild Card dogfight they couldn’t win. There were lots of reasons for that, actually.

Still, Daniel Murphy was a pennant-race Met and a Shea Stadium Met. There aren’t many of those left: him, Wright and Santana plus September ’08 coffee-sippers Jon Niese and Bobby Parnell. If the Mets had made that postseason, lefthanded Murph would’ve been the starting left fielder in Games One and Two of the NLDS at Wrigley Field against righties Ryan Dempster and Victor Zambrano. He might’ve sat in Game Three at Shea against Rich Harden, but who knows? The Mets didn’t beat out the Brewers, didn’t play the Cubs and have not since gotten within wishing distance of postseason play. Yet when I got to gaggle around Murph at the Mets’ holiday party in December 2011 and heard him tell one of my fellow bloggers that “there’s no better place to win than in New York City,” I knew he was talking not from cliché or watching other teams win on TV. For nearly two months, Daniel Murphy was a part of winning — or almost winning — in New York City, and as long as we were close enough to dream, there was indeed no better place.

I think it’s that recollection of rookie Daniel Murphy participating in late-season drama and rehabbing Daniel Murphy implying he remembered what it was like that made me a little sad the other day when I read his remarks on the current state of Met affairs. Murph was the latest in a line of Mets to visit areas hard-hit by Superstorm Sandy this winter — Far Rockaway, on Wednesday — and was asked, after doing his good deed, what he thought of what his team has done and hasn’t done this offseason.

He spoke like a veteran, like someone with a proprietary as opposed to a mercenary interest in the long-term fortunes of his team, like someone who’s worked in the same place for quite a while. He found reasons for optimism, he put a good face on things that could’ve gone better, but then he said something that managed to remind me how long ago the last Met pennant race really was. Acknowledging the unsettled nature of the outfield — a pasture Murph wisely abandoned several seasons ago — he spoke up for one his new prospective teammates:

“I’ve heard nothing but good things about Collin Cowgill. I actually got a text message right after he [was traded to the Mets] from Andy Green, who used to be in our organization. He said that we’re going to love this guy — that he comes to play hard every day. He said he’ll really fit in well in the clubhouse. While it may not be big-league free-agent splashes that we’ve made so far, I think we’ve added some pieces that are definitely going to help us.”

I wouldn’t have expected Murph to mutter, “Collin Cowgill? Who the hell is that? Where the [bleep] is Justin Upton?” Nevertheless, that scouting report…“he comes to play hard every day”? Is that unusual? Having watched the Mets too closely for my own good this past August and September, sadly I know the answer. I can see why Murph would value having a teammate who plays hard every day, since he was one of the few Mets I was convinced continued to do so after 2012 went irretrievably south. But I always thought that sort of thing was a given.

And “he said he’ll really fit in well in the clubhouse”? I wonder what that’s code for. It put me in mind of Henry Hill’s explanation of how wise guys talk: “You’re gonna like this guy. He’s all right. He’s a good fella. He’s one of us. You understand?” In light of how the Mets have disintegrated second half after second half in this decade, they could use someone who doesn’t fit snugly within their milieu. Asking a projected platoon center fielder with 216 plate appearances under his belt to be an agent of change might be a bit much, but here’s hoping Collin Cowgill shakes things up more than he conforms to the established norm of his new surroundings. (As long as he doesn’t wear a t-shirt to the clubhouse, heaven forefend!)

What really got me, though, was Murph’s source for all things Cowgill. “I actually got a text message…from Andy Green, who used to be in our organization.”

Andy Green? The Met for four minutes (OK, games) in 2009? Murph’s still in touch with Andy Green? I couldn’t decide whether that was touching or strange. A person can forge a lifelong friendship from the briefest of encounters, but that’s people. These are ballplayers. Daniel Murphy is a Top 50 Games Played Met. Andy Green took a Citi Field tour and wandered onto the diamond against the Giants. They actually shook hands?

That impression, however, doesn’t take into account the big baseball fraternity and Spring Trainings and minor leagues. Murph and Green were together in the organization in 2010 even though neither played in the majors. Why shouldn’t they have gotten to know each other? Further, what the hell do I know about Andy Green besides how quickly he was here and gone? I didn’t know, for example, that since he and I crossed paths in 2009 (he was batting and I was ironically cheering him on at the tail end of a blowout loss from the top of Promenade) Andy Green has become a manager. Not of a Dick’s Sporting Goods, to borrow a line from Moneyball, but the Double-A Mobile BayBears, affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks, for whom Green wasn’t playing much before coming to the Mets and playing hardly at all.

Mobile is Green’s new managerial assignment. Last year, his first as a skipper, he helmed the Missoula Osprey of the Pioneer League. Turns out that as Andy was passing through the Mets, he was realizing his real future was as a molder of young men — or something like that. “It was at that time when I was walking other teammates through pressure situations and game situations and talking about the game,” he told the Missoulian last summer, “that I began to really fall in love with the game and began to really want to coach after my playing days were done.”

So maybe there’s more than meets the eye to Daniel Murphy citing Andy Green’s endorsement of Collin Cowgill. Or maybe it’s just the way guys in the fraternity talk about other guys in the fraternity. Or, perhaps, Murphy’s climb back from outfield infamy and knee injury and evolution toward becoming a representative second baseman and doubles-producing machine had something to do with a little advice he got along the way from a washed-up utilityman who knew more about baseball than one would have guessed from examining his statistics.

The only things I can really glean until Cowgill proves a mighty contributor or a negligible addition to the 2013 Mets, is Daniel Murphy played on the 2009 Mets with Andy Green; 2009 was both pretty long ago and the beginning of the ongoing dismal epoch in which the Mets remain stuck until an 82nd win is secured; and Murph goes back even further than that — to another stadium and another era, one when Mets fans weren’t reduced to parsing quotes about spare outfielders because we were far too excited about our chances in the season ahead to dive headfirst into that kind of minutiae.

by Greg Prince on 14 January 2013 12:41 am The Mets tell us things in dribs and drabs. Like who’s gonna fill out the starting rotation. Like who’s gonna be in the outfield. Like what they’ll be giving away besides the occasional late-inning lead.

The franchise that keeps as low a profile as possible in winter (no fanfest, no caravan, as little noticeable effort at generating enthusiasm as possible) quietly scheduled seven promotional dates for April and May; I assume they’ll see how the first two months go before committing to a full baseball season in 2013. The goodwill surprises of 2012 are back — Banner Day and bobbleheads portraying Mets greats (Ron Darling on April 21 and John Franco on May 25) — along with hardy perennials the magnetic schedule, the drawstring bag, Bark in the Park and one Mr. Met Dash thus far. Huzzahs for banners and bobbles, no complaints for the rest.

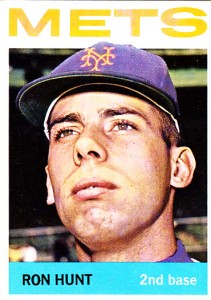

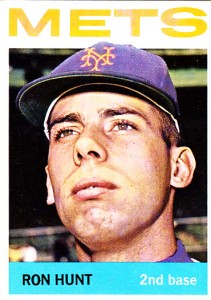

As for June through September, we can’t judge what we can’t see, but we’ll make a suggestion since all we see is a gaping void: Ron Hunt Day. Or Ron Hunt something.

Ron Hunt: Something else for Mets fans from 1963 to 1966. Ron Hunt — the first player the Mets can be said to have stolen from somebody else (the Milwaukee Braves, who sold their 21-year-old minor league infielder to New York following the 1962 season).

Ron Hunt — the Mets’ first young star of any discernible wattage.

Ron Hunt — who drove in the first game-winning run the Mets could claim in his very first season, which just happens to have been 50 years ago, getting the Mets off to their fastest start ever (1-8 in 1963 versus 1-9 in 1962).

Ron Hunt — who was the first Met to win votes for anything that wasn’t ironic in the world at large, finishing second to Pete Rose for National League Rookie of the Year in 1963.

Ron Hunt — who can’t leave his body to science because he gave it to the Mets via 41 hit-by-pitches between 1963 and 1966, still a career franchise record.

Ron Hunt — whose heart and soul was nearly as orange and blue as his body was black and blue, an assessment gleaned from his reaction to being traded with Jim Hickman for Tommy Davis on November 29, 1966:

“I don’t want to leave. I don’t want to leave the New York fans. These have been the greatest years of my life. I wanted to stay here and be part of this team and play in the first World Series for the Mets. My wife is all broken up, too. She loved New York and the people and all the kindnesses. We can’t forget the flowers Mrs. Payson sent us and all the nice letters I got when I was in the hospital. I don’t want to be traded.”

Then, as if for emphasis, he repeated the sentiment:

“I don’t want to be traded.”

As Maury Allen put it in The Incredible Mets, “Ron Hunt, the toughest kid on the block, was in tears.”

Finally, Ron Hunt — the starting second baseman for the National League in the 1964 All-Star Game…which was played at…that’s right, Shea Stadium. Hunt was a second-year player, Shea was a first-year ballpark and the two entities trotted out to the baseball spotlight on July 7, tipping their caps, taking their bows and making an impression. Hunt was judged by his peers (there was no fan voting) the best second baseman in the senior circuit for the first half of that season. He was chosen to start over future Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski and he singled on the first pitch he saw from soon-to-be Cy Young winner Dean Chance. Two years later, Hunt became the first two-time All-Star in Mets history, sharing backup second baseman duties with another future Hall of Famer, Joe Morgan.

Until this year, Ron Hunt has been a New York Mets All-Star more often than the New York Mets have been an All-Star Game host. Now Hunt and the Mets move into a tie. The All-Star Game comes to Citi Field on July 16. Hopefully the Mets will have more than one representative. Matt Harvey was a promising rookie last year who might blossom this year, as Hunt did from 1963 to 1964, and they do have some youthful promise if you avert your gaze from the outfield. Maybe this is the year Ruben Tejada or Jon Niese or Ike Davis or the MLB Network’s tenth-best second baseman Right Now Daniel Murphy moves up in leaguewide esteem. Or maybe we just hope David Wright stays healthy and Pablo Sandoval’s fan club takes off the first week of July.

We don’t know who we’ll be able to send out for cap-tipping and bow-taking in 2013. We do know who we had in 1964. We do know an All-Star Game in Flushing is a rare enough phenomenon that hosting a second one is a great excuse for celebrating the first one just short of its golden anniversary. We also know that Hunt, who went on to a solid if bruised career that lasted through 1974 with four other clubs (including 50 HBP in one year, for cryin’ out loud), was nervy enough to opine in late 1966 that someday the Mets would be World Series-bound. That such talk could be less than three years from reality — and that the trade of Hunt and Hickman for Davis would help set the stage for 1969 given that Davis and Jack Fisher were flipped to the White Sox for Tommie Agee and Al Weis in 1967 — seemed as unlikely as clearing October 2015 on our calendars right now for bigger and better things.

But Hunt talked the talk. He walked the walk…right after taking a ball to the ribs or the thigh or the shoulder. He loved being a Met even after the not exactly enlightened Wes Westrum questioned his desire to play through pain. The affection shouldn’t be unrequited, nor should it be considered to have an expiration date that’s lapsed. The All-Star festivities themselves are a Major League Baseball production, but since the Mets have used their hosting status as an inducement for season-ticket sales, it’s reasonable to infer they will, by June, make the All-Star Game the focus of some kind of promotion. Knowing the Mets, it will involve a logo on a plastic cup.

Make it about more than the logo. If we can indulge in the language of marketing, activate some Mets-hosted All-Star equity this summer. Give us 1964 All-Star Day at Citi Field. Issue an invitation to every living 1964 All-Star who graced Shea Stadium’s foul lines 49 years ago. Give us a chance to stand and applaud for Willie Mays, for Henry Aaron, for Brooks Robinson, for Orlando Cepeda, for Juan Marichal, for Sandy Koufax, for Billy Williams, for Jim Bunning, for Mazeroski, for Chance, for Jim Fregosi and Joe Torre even. And save for last, as our hometown favorite, Ron Hunt of the New York Mets.

If you want to give us a Ron Hunt bobblehead while you’re at it, Gold’s Horseradish should be honored to sponsor. If you want to get creative with the Mets Hall of Fame and induct three splendid second basemen — seems Felix Millan and Edgardo Alfonzo are overdue — while perhaps waiting to sync up with Cooperstown on Mike Piazza, that wouldn’t be inappropriate, either. But if you could give Ron Hunt a day he’ll never forget while giving Mets fans the impetus to remember their first incandescent spark of hope, that would be a truly All-Star promotion.

Read more about Ron Hunt and all the Mets who created Amazin’ wins in their time in The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), available via Amazon.

Image courtesy of Shlabotnik Report.

by Greg Prince on 9 January 2013 11:49 am Flushing, N.Y. (FAF) — Mike Piazza earned near-unanimous election into the Hall of Greg, it was announced Wednesday. Piazza made it on the first ballot with a percentage of 98.83%, a total second only to Tom Seaver’s 98.84%. It was the highest possible percentage available, since the rules of the Hall of Greg state no player may collect a greater proportional vote total than Seaver’s.

Piazza will enter the Hall of Greg as a Met, same as previous first-ballot inductees Seaver (1992), Willie Mays (1979), Keith Hernandez (1996), Gary Carter (1998), Nolan Ryan (1999), Eddie Murray (2003) and Rickey Henderson (2009). Richie Ashburn, Duke Snider, Yogi Berra, Warren Spahn, Casey Stengel and Gil Hodges, elected by the Hall of Greg’s Veterans Committee upon the institution’s founding in the early 1970s, were also inducted as Mets. (Roberto Alomar’s lifetime ban from Hall of Greg consideration remains in effect.)

“This wasn’t a ‘no-brainer,’” said a Hall of Greg spokesman. “We used our brains. We used our common sense. We used our memories. We used our computers. We used everything that was available to us. Clear eyes, full hearts…Mike couldn’t lose.”

The newly elected Hall of Greg member will be asked to choose which Mets cap he wants to be inducted in at ceremonies this summer. He can choose among traditional royal blue, all black or the hybrid black-blue model in which he often played. It’s also been suggested a cap bearing the initials of the New York Police Department would be an appropriate homage to the memorable night of September 21, 2001, when the greatest-hitting catcher in baseball history launched the home run that won the first baseball game played in New York after 9/11 and symbolized the city’s subsequent recovery efforts in the opinion of some.

It was just one of many epic home runs Piazza blasted for the Mets, most of them searing themselves into the consciousness of Mets fans forever. He hit 220 homers as a Met — 427 overall — along with six in the postseason (five as a Met). Nobody in major league history hit more as a catcher than his 396.

Piazza’s debut as a Met marked a turning point in the fortunes of the franchise, as he lifted a then-middling club into serious playoff contention for the next four seasons, leading them to the National League Championship Series twice and the World Series once. He represented the Mets in seven All-Star Games and was selected to the National League squad on five other occasions. Overall, he was a singular icon of New York baseball for most of a decade and the Mets’ biggest star ever this side of Seaver. The pair, as catcher and pitcher, were given the honor of the ceremonial final pitch upon Shea Stadium’s closing in 2008 and first pitch when Citi Field opened in 2009.

No other candidates on the 2013 Hall of Greg ballot were elected. Shawn Green, Julio Franco, Roberto Hernandez, Jeff Conine and Aaron Sele each received token support in recognition of long and meritorious careers, in line with the Hall of Greg’s philosophy that everybody who wore a Mets uniform and makes its ballot deserves at least a glint of recognition.

Piazza could not be reached for comment as he is reportedly in the final stages of completing his book, Long Shot, slated for February release. A Hall of Greg spokesman indicates great interest in reading the book, “but it’s not like anything in there is going to change what we think of what Mike did as a Met between 1998 and 2005.”

by Greg Prince on 8 January 2013 4:54 pm Richard Ben Cramer, a journalist like no other I’ve read, clearly kept his ears open as well as his eyes. Cramer, who just passed away at the age of 62, listened. Listening is so much more effective than talking. Too many people who ask questions — journalists and otherwise — spend too much time holding the ball on their side of the conversation. Shut up, I kind of want to say politely, and let your subject answer.

Cramer did that. Cramer had to have. You don’t deliver as much sound as he did to a story without a very active ear. A good eye, too, and Cramer had that working at all times. The man heard what was going on and he noticed what was going on. It was a combination that could cut glass when set to the printed word.

I love to read baseball. I love to read politics. Richard Ben Cramer was so sharp at writing both that I could read him on either subject all day and all night — and I literally did. Cramer’s masterwork on politics, What It Takes: The Way to the White House, accompanied me on a cross-continent sprint the year it came out, 1992. I had to fly all night to Vancouver and fly all night the next night back to New York. What It Takes checked in at 1,047 pages, though who was counting? Today they’d make me buy it its own ticket. I’d have bought it one then if that’s what it had taken for me to take What It Takes where I had to go. It was the epitome of I-can’t-put-this-down storytelling.

What It Takes is a hexagon-shaped profile of approximately half the serious presidential primary field of 1988, when no incumbent was running, thus everybody in both parties was giving the race a spin. Cramer burrowed his way into a half-dozen heads that carried the loftiest of electoral aspirations. In so many words, he wondered what kind of a person thinks he’s fit to be leader of the free world? So he set about finding out, not just by getting to know his subjects — Messrs. Bush, Dole, Dukakis, Biden, Hart and Gephardt — but just about everybody who’d ever known them. Any one would’ve been a biography for the ages. But six? Via who knows how many hundreds of conversations and filtered through a half-dozen psychographic dialects that remained true to their subjects while never letting you forget they were gathered together under one hardcover roof?

Amazin’.

Which, you might say, is where the reader enters the What It Takes story, on October 8, 1986, Game One of the NLCS at the Astrodome. It was the beginning of the George Bush campaign trail and it just happened to cross paths with the Mets’ pursuit of a pennant:

Tonight, George Bush will shine for the nation as a whole — ABC, coast to coast, and it’s perfect: the Astros against the Mets, Scott v. Gooden, the K kings, the best against the best, the showdown America’s been waiting for, and to cut the ribbon, to Let the Games Begin…George Bush. Spectacular! Reagan’s guys couldn’t have done better. It’s Houston, Bush’s hometown. They love him. Guaranteed standing O. Meanwhile, ABC will have to mention he was captain of the Yale team, the College World Series — maybe show the picture of him meeting Babe Ruth. You couldn’t buy better airtime. Just wave to the crowd, throw the ball. A no-brainer. There he’ll be, his trim form bisecting every TV screen in the blessed Western Hemisphere, for a few telegenic moments, the brightest star in this grand tableau: the red carpet on the Astroturf; the electronic light-board shooting patterns of stars and smoke from a bull’s nose, like it does when an Astro hits a home run; the Diamond Vision in riveting close-up, his image to the tenth power for the fans in the cheap seats; and then the languorous walk to the mound, the wave to the grandstand, the cheers of the throng, the windup…that gorgeous one-minute nexus with the national anthem, the national pastime, the national past, and better still…with the honest manly combat of the diamond, a thousand freeze-frames, a million words worth, of George Bush at play in the world of spikes and dirt, all scalded into the beery brainpans of fifty million prime-time fans…mostly men. God knows, he needs help with men.

So George Bush is coming to the Astrodome.

Disaster in the making.

“The thing is,” Cramer continued, “it couldn’t just happen. George Bush couldn’t just fly in, catch a cab to the ballpark, get his ticket torn, and grab a beer on the way to his seat. No, he’d come too far for that.” Meaning? Meaning there’d be six or seven pages on all the logistical ins and outs it took to get a sitting vice president to the mound of National League playoff game; five more on how Bush embraced the job he was compelled to settle for six years earlier; the introduction to the Astrodome scene of his explosive eldest son, George, and the element of danger he represented as he expressed his displeasure over the less-than-royal treatment his dad’s operation had allowed to transpire in his direction (“SEATS AIN’T WORTH A SHIT. I GUESS THE BOX GOT A LITTLE CROWDED…”); then back to the elder Bush and a hearty helping of the veep’s well-honed love of all things jockish, including a nugget about his friendships with Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan…all of which builds up to the “disaster” of a bulletproof vest-encumbered first pitch which Cramer foretold:

[H]is eyes still following the feckless parabola of his toss, which is not gonna…oh, God!…not gonna even make the dirt in front of the plate, but bounce off the turf, one dying hop to the…oh, God!

And as he skitters off the mound toward the first-base line, and the ball on the downcurve of its bounce settles, soundless, into Ashby’s glove, then George Bush does what any old player might do in his shame…what any man might do who knows he can throw, and knows he’s just thrown like a girl in her first softball game…what any man might do — but no other politician, no politician who is falling off the mound toward the massed news cameras of the nation, what no politician would do in his nightmares, in front of fifty million coast-to-coast, prime-time votes:

George Bush twists his face into a mush of chagrin, hunches his shoulders like a boy who just dropped the cookie jar, and for one generous freeze-frame moment, buries his head in both hands.

I love to read baseball. I love to read politics. What were the odds the two would converge this way?

Don’t care for politics? Cramer wrote baseball straight, too. His Joe DiMaggio: A Hero’s Life explained to me once and for all why my dad and his generation revered Joltin’ Joe beyond mere statistical measurement and more than hinted at why that reverence wouldn’t fly today. He was less iconoclastic toward Cal Ripken, Jr., at the height of streakmania in 1995 for Sports Illustrated, but every bit as characteristically sharp in observing the scene around him:

It’s a stinkin’-hot night at the ballpark — near 100°, the air is code red — and the Orioles are playing the cellar-dwelling Blue Jays. Still, it’s got to be a big night: It’s Coca-Cola/Burger King Cal Ripken Fotoball Night. That is, it’s the sort of ersatz event that is a staple of baseball now that payrolls are fat, attendance is slim, and the game — well, no one trusts the game to be enough. These new Orioles yield to no club in the promotional pennant race. There’s Floppy Hat Night, Squeeze Bottle Night, Cooler Bag Night. There’s an item called the NationsBank Orioles Batting Helmet Bank, and there’s the highly prized Mid-Atlantic Milk Marketing Cal Ripken Growth Poster. They are all a stylistic match for the graphics on the scoreboard that tell you when to clap or the shlub whose bodily fluids are draining into his fake-fur Bird Suit while he dances on the dugouts for reasons known only to him.

Still, as a celebration of the Hardest-Workin’ Man in Baseball, the hero of this Old-Fashioned Hardworkin’ Town, the Cal Ripken Fotoball is my personal favorite, perfect in every detail. There is the F in the name — gives it klass, and it’s korrect, because there’s no photo on the ball. There’s a line drawing of Cal’s face, with a signature across the neck. The signature is of the artist who made this genuine-original line drawing from a genuine-official photo of Cal. And then there’s the plastic wrapper — says it’s all Made in China. I like that in a baseball. And one key word: NONPLAYABLE. In other words, don’t throw or hit it, or this fotobooger will come apart.

Hours before game time, I wanted to ask Cal about his Fotoball. I wanted to ask how it feels to be the icon for baseball and Baltimore. But he’s hard to catch in the locker room. He has his locker way off in the corner, where his dad used to dress as a coach. The official-and-genuine Oriole explanation is that the corner affords him room for two lockers — one extra to pile up all the stuff fans send him. But it’s also unofficially helpful that there’s an exit door in that corner, and anyway it makes Cal plain hard to get to. (One day early in the season I was blocked entirely by the richly misshapen and tattooed flesh of Sid Fernandez.) And if you’re lucky enough to catch Cal, you’re still not home free: Even local writers — guys Cal knows — find that out. “Angle your story,” he might say, without looking at the writer, his eyes still on the socks in his hand. “Yeah…but what’s the angle?”

So the writer must explain what he means to write. “Cal, it’s just about all the second basemen you’ve had to play with — you know, 30 different guys to get used to.”

“No,” Cal says to his socks. “Doesn’t do me any good to answer that.”

See, these days, just a handful of games from Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,130 consecutive starts, he’s playing writers like he always plays defense, on the balls of his feet, cutting down the angles: How is this gonna come at me? Where should I play it? Positioning (forethought, control) has always been his game. And streak or no streak, Cal still has to play the game his way — that is, correctly: He’s got to click with his second baseman.

Fifteen years after I first read that, I wrote this, about a Mets promotion called Collector’s Cup Night. It’s a piece people remind me of to this day. I realized today, as I sought out his writing, that my Collector’s Cup was a direct descendant of Richard Ben Cramer’s Fotoball. He paid attention and he wasn’t so occupationally immersed in his habitat that he was incapable of making note of its occasional absurdities. To him, it was a Fotoball. To me it was the notion that we were actively Collecting Cups. His Ripken story was about far more than a silly sponsored promotion, but a little slice of it served as a quiet inspiration to some writer somewhere. A multitude of his slices have over time, actually.

Richard Ben Cramer’s writing was just that sharp.

by Greg Prince on 7 January 2013 4:47 am The New York Mets have thus far this offseason, when not trading reigning National League Cy Young Award winners, procured the services of the following players with non-Mets major league experience:

Josh Rodriguez, infielder, 28 years old, 7 MLB games (2011);

Jamie Hoffmann, outfielder, 28 years old, 16 MLB games (2009, 2011);

Anthony Recker, catcher, 29 years old, 27 MLB games (2011-2012);

Carlos Torres, pitcher, 30 years old, 44 MLB games (2009-2010, 2012);

Greg Burke, pitcher, 30 years old, 48 MLB games (2009);

Brandon Hicks, infielder, 27 years old, 55 MLB games (2010-2012);

Andrew Brown, outfielder, 28 years old, 57 MLB games (2011-2012);

Collin Cowgill, outfielder, 26 years old, 74 MLB games (2011-2012);

Aaron Laffey, pitcher, 26 years old, 148 MLB games (2007-2012);

and Brian Bixler, infielder-outfielder, 30 years old, 183 MLB games (2008-2009, 2011-2012).

Among them, these 10 players, born between 1982 and 1986, have played a combined 659 games in the major leagues since 2007. By comparison, I recently turned 50 and have attended, by my count, 582 games in the major leagues since 1973.

It would be easy to say, “I’ve never heard of these guys,” and, in fact, I will say it: I’ve never heard of these guys, even if that’s not exactly true. Josh Rodriguez was in the Mets system last year and I’m pretty certain I noticed his name during a Bisons telecast or two. And six of these fellows — Torres, Burke, Brown, Cowgill, Bixler and Hicks — are certified by Baseball-Reference to have played against the Mets in games I watched and sort of remember.

But mostly, I’ve never heard of these guys. It’s as if John Hughes had lived to write and direct Moneyball.

***

Monday, January 7, 2013

New York Mets Spring Training Complex

Port St. Lucie, FL 34986

Dear Mets Fan,

We accept the fact that you’ve had to sacrifice several seasons of contention for whatever it is the Mets did wrong. But we think you’re crazy to make us report to camp early to tell you who we think we are. You see us as you want to see us, in the simplest terms and the most convenient definitions. But what we found is that each one of us is…

• a minor league free agent

• a waiver claim

• a cash-considerations purchase

• an agate-type acquisition

• and somebody you’ve never heard of.

Does that answer your question?

Sincerely yours,

The Afterthought Club

(We see Bixler walking across the baseball field as he thrusts his fist into the air in a silent cheer and freezes there. Cue Simple Minds.)

***

R.A. Dickey could rightly be invoked in this space as the unheralded December transactionee who delightfully surprises the smirk off our cynical faces, therefore proving rushed judgment should always be held in abeyance. Swell — but I’d heard of Dickey before we signed him in the kind of ink-conserving deal that brought us these fill-in-the-blanks. Of course I’d heard of Jason Bay, too, so glowing advance notices are not ironclad guarantees of anything.

Listen, if any given underknown quantity in this bargain-bin bunch works out by way of a key strikeout or a rally-extending hit, we’ll praise him as a good get at least until his unproductive outweighs his beneficial. If a very big moment transpires, the likes of me will swear years later that, no, this guy wasn’t totally worthless, he blasted that homer/won that game that time. And if he rolls out a success story even a twentieth the size of Dickey’s, well, we know who we’re nominating for Executive of the Year.

For now, though, I’ve never heard of these guys.

Then again, they’ve never heard of me.

by Greg Prince on 6 January 2013 2:30 pm There really are Mazzys. They look nothing like their namesake Lee Mazzilli, but who besides Lee Mazzilli ever did? I won my third consecutive Mazzy for writing about the Mets Saturday night. The first two were notes in blog posts, which was plenty nice as it was. The third was handed to me like it was a real thing. It was a real thing. It’s not every day somebody wants to hand you an award. When somebody does, you accept it graciously and you say thank you very much.

So thank you very much to the Mets Police — chief Shannon Shark and enforcer Media Goon — for the honor and, even better, the merging of blogger whimsy with reality-based event-planning and making an evening out of the Mazzys. That meant not just a lighthearted awards program that focused on blogging yet touched on many matters Metsian (R.A. Dickey won two, even though he in 2013, like Mazz in 1989, will be wearing Jays blue), but the gathering of several dozen Mets fans who would otherwise have been paying homage to our 1962 batting coach Rogers Hornsby by staring out the window and waiting for spring.

Congratulations to my fellow Mazzy recipients. Congratulations to all who were nominated. Congratulations to all who weren’t nominated but could’ve been. Congratulations to Mets fans everywhere is my philosophy. We are a 108-54 tribe, no matter what kind of record we are saddled with in any given year.

The Mazzys were bestowed in the hamlet of Woodside, which was perfect for my LIRR needs and just uncold enough around 5 PM Saturday to dream. It wasn’t really still January, was it? Pitchers and catchers must, at the very least, be long-tossing somewhere. And if Stephanie and I are in Woodside, that must mean we’ll be changing for the 7 to Flushing, right? Right?

Maybe not, but this was OK, too.

Mets Police picked Donovan’s as site of the Mazzys. Good choice based on locale, reputation and the room they assigned us; not so good based on our food practically never showing up. There were drinks, there were awards, there were greetings for old friends, there were introductions to new acquaintances, there was passionate Mets talk laced with reverence for our Piazza-packed past, wariness of our Dickey-deprived present and vague hope directed toward our undefined future…but there was no sign — none — that our complicated order of one cheeseburger and one turkey burger was en route. I began considering the efficacy of dipping my Mazzy in ketchup on the chance it would taste like chicken. It took three inquiries before we could tease the following status report from the kitchen:

“Your order is up.”

I’m not sure what that meant exactly, but it didn’t seem to indicate the presence of burgers was nigh. Half the room was paying its checks and zipping its coats while we were embroiled in tense hostage negotiations with the waitress — “Listen, can just we pay for the drinks? We have a train to catch.” She eventually agreed to release the burgers in aluminum receptacles so we could take them to go. We made our train, got lucky at Jamaica and found our dinner still warm when we broke it out of its plastic bag at home. I turned on the Packers and Vikings and then turned them off almost immediately, palpably insulted that after we put on our Mets stuff and took a trip to Woodside, baseball season had somehow failed to ignite.

My Mazzy, meanwhile, found a home between esteemed bobbleheads of Keith Olbermann and Buddy Harrelson. I’m sure the three of them will have plenty to discuss as they, too, stare out the window and wait for spring.

From medium-rare to well-done: Matthew Callan’s Amazin’ Avenue review of The Happiest Recap: 50 Years of the New York Mets as Told in 500 Amazin’ Wins (First Base: 1962-1973). And if you’ve ever wanted to read a book written by a Mazzy-winning author, have I got a link for you…

|

|