The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 4 January 2013 12:00 pm We’re into the mid-’90s, and the makeover of The Holy Books … well, it’s dragging a bit.

I’ll sum up the problem with a string of numbers: 45, 22, 19, 20, 17, 35, 8, 9, 10, 8, 13, 13, 9, 17, 9, 14, 16, 14, 13, 15, 13, 12, 15, 12, 10, 13, 4, 14, 20, 13, 24, 20, 19, 25, 19, 24, 26, 20, 22, 17, 29, 21, 29, 24, 28, 22, 27, 26, 21, 22, 23.

That’s the number of Mets to make their debuts each season in club history. To me, the ebb and flow makes for an interesting portrait of how baseball’s changed over time. The Mets of the ’60s used a lot of players — the 45 shouldn’t count, as every ’62 Met was making his debut, but 1967’s 35 new Mets remains the franchise high. But in the ’70s and ’80s the numbers were relatively small. Joshua’s initial interest in the project (and greed for his promised $50) carried him through the ’60s well enough, and in the ’70s and ’80s he was able to reorder each year’s handful of Mets in no time — 1988’s four new Mets (the franchise low) took about six seconds. But starting in the ’90s the annual total rises into the twenties and mostly stays there, and by now the kid’s sick of sorting cards and inserting cards and checking the order of cards, and he’s wondering if $50 was really such a deal.

Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom. Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom.

Dad: Darrin Jackson had Graves’ disease. I don’t know what that is. No, it probably didn’t make sense to trade for him. Except it let us get rid of Tony Fernandez, who wasn’t any good because he suffered from kidney stones and a lack of interest in being a Met, which should be called Alomar’s disease.

Son: This is really inspiring, Dad! Never mind R.A. Dickey — let’s go get Opening Day tickets!

Sometimes you’re better off saying nothing.

And the cards? We’ve gone from the beautiful Pop-Art cards of the ’60s with their painterly portraits to the goofy explosion of clashing colors that was the late ’70s, through the industrial-looking ’80s, and now we’re in the mid-’90s, when baseball-card design turned crass and high-tech and weird. Cards are gold, and silver, and embossed, and have lenticular layering to produce lame 3-D effects, and are tarted up with little distorted mirror images, and festooned a multitude of other bad ideas. (Kevin Lomon’s ’95 Fleer Update card is the single worst-looking piece of cardboard in The Holy Books.)

We’ll fight through it — the kid perked up a bit at the sight of Edgardo Alfonzo, and soon enough we’ll reach Mike Piazza, and players he actually remembers, and then we’ll be in sight of the finish line.

But as the above indicates, for me the memories have mostly been about baseball cards — and those memories have taken me back to a place that’s not entirely good.

I started buying baseball cards again by accident in the late ’80s, as you can read about here. (Short answer: It was Rickey Henderson’s fault.) At the time my folks lived in St. Petersburg, Fla. It’s a decently lively town now, but this was the late ’80s, when the city still had the rather cruel nickname of “God’s waiting room.”

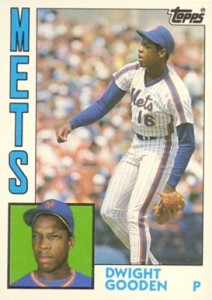

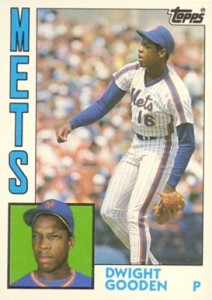

Like every other place then, it was going through the baseball-card boom, and it was my chief hunting grounds. I was working on a long, long list of cards I wanted, and my top two targets were the most expensive Mets rookie cards of relatively recent vintage: the ’83 Darryl Strawberry and the ’84 Dwight Gooden. They were pricey to the point of being unobtainable — I wasn’t even thinking about a ’68 Ryan yet, or a ’67 Seaver, or high numbers, or any of the other things I’d spend too much money and time obtaining later.

I found a Straw with a bit of a wrinkle at a card show in a half-deserted mall that mostly sold prosthetic limbs — a happy defect that took it down to half-price or so. But the Gooden? Oh boy. The Mets had just left for Port St. Lucie, and despite his recent cocaine woes Dwight Gooden was a sure-fire Hall of Famer, a Met and a hometown kid. The Internet was still for physicists, and auctions were conducted by members of the horsey set holding up paddles — if you were in St. Pete and wanted a Gooden rookie, you were going to pay for it.

The central St. Petersburg of a quarter-century ago contained many forlorn, sun-blasted stretches of asphalt occupied by dumpy cinder-block buildings in which indifferent commerce sometimes occurred, and one of those sad buildings was a baseball-card shop run by a guy named Ray and his mostly invisible wife.

Ray was an asshole. He was given to scheming and complaining and was truculent unless he thought he was about to con you out of something, in which case he would feign being friendly for a minute or two before getting distracted and going back to being Ray. In other words, he was like 90% of the people who became baseball-card dealers during the years when price guides were bibles and cards were investments and buyers and sellers alike were mostly unbearable.

Ray hated customers and kids and baseball cards and baseball, and the only thing that changed was the order in which he ranked those hatreds. Meanwhile, I thought I liked Ray. I actually hated him, for all the obvious reasons, but I hadn’t figured this out yet. I thought I liked him because I knew he was teaching me how to tolerate unpleasant people who had something you needed, which I sensed was a valuable skill. That much I was right about.

Anyway, I needed Ray for three reasons:

1. His shop was the closest baseball-card store to my parents’ house at the far southern end of St. Petersburg.

2. His shop was also the best baseball-card store in the area. Ray hated baseball cards, but he had a ton of them — I suspect he’d bought out some other dealer, who’d stuck him with boxes and boxes of unsorted commons from all sorts of years, including hopelessly obscure sets nobody else had and nobody particularly wanted but me.

3. Ray had a 1984 Topps Traded Dwight Gooden.

I would get a little money together and go see Ray, hoping to cross off a few things from my endless want list. If Ray were there, I’d ask him about various sets, which he’d claim he didn’t have because he didn’t want to get up out of his lawn chair behind the counter. Eventually I figured out I could rouse him into vague motion by pretending I needed an obscure card he thought was expensive. If I could get him to pull down three or four boxes of cards in search of things, he’d get pissed off and bark at me to just come behind the counter and look myself, which is what I’d wanted in the first place. I’d put together whatever stack I could afford, then police Ray’s slow-motion checking through the latest price guide, correcting the errors of price and condition that somehow inevitably went in his favor.

And then I’d ask him about that Gooden rookie.

When I’d do this Ray’s eyes would gleam, he’d grin, and then he’d begin to fidget. The card was sharp but miscut, which should have knocked a fair amount off of its value. Ray knew this, or rather Ray would admit this in the face of ruthlessly presented evidence, but he would always respond vaguely that it was no big deal because he knew a guy who could get the card fixed somehow, and in the meantime he wanted to be paid as if it were a perfectly cut Dwight Gooden rookie card. I refused to do this, as did everybody else, and so for a year or two the Gooden rookie sat in one of the carousels atop Ray’s display case, awaiting its visit with Ray’s vague associate and mocking me with its unavailability.

Until one day, for my birthday, I opened up a small package and found … a Gooden rookie. I exulted, hugged my mother, then pulled back and looked at it more closely.

“Tell me,” I said, “that you didn’t buy this from Ray.”

My mom swore she hadn’t, but that miscut was like a fingerprint. She confessed and I hugged her again, a little annoyed that Ray had extracted undeserved money from my mother but mostly grateful that my search was over.

When Joshua and I came to the mid-’80s in the Holy Books makeover, I saw that a few cards I’d selected weren’t particularly attractive choices: Why did I pick Topps ’89 cards of Rick Aguilera and Randy Myers in which they’re staring at the Topps photographer like they’re at the DMV? I knew there were better cards for both, so I took a peek on eBay — and discovered I could get the entire ’88 set, plus the traded cards, for $3. Including shipping.

That was good — and yet it was disappointing to discover the ’88 Mets, those winners of 100 games, had become a collector’s afterthought.

In The Holy Books, Dwight Gooden is represented by his ’92 Topps card, on which he’s called Doc. I’d never liked the formalizing of the nickname — it smacked of rebranding, of hubris, of tempting fate. I decided I could and would do better by Dwight Gooden. But what card would be best for him?

I went back to eBay, wondering … and wondering if I wanted to know.

Ray’s baseball-card store is long gone. I don’t know what’s there now — maybe it’s an artisanal coffee shop where perky baristas are happy to see customers.

I assume Ray is dead, though I wouldn’t be astonished to learn he’s hawking Skylanders figures on eBay from his lawn chair and ripping people off with handling charges.

Dwight Gooden is 48 years old. He retired with 194 wins, and when we hear his name in the news our first instinct is to worry.

And a 1984 Topps Traded Dwight Gooden rookie? Perfectly cut, with four sharp corners, it will cost you $7.50 on eBay. Including shipping.

by Jason Fry on 2 January 2013 10:46 pm Greg has always appreciated The Holy Books — my three binders of baseball cards, with each Met represented by a single card organized by the year of their Mets debut — while making simultaneously gentle and pointed inquiries about their administration. His biggest objection? It’s been that The Holy Books are organized alphabetically within each year — Ashburn to Zimmer in ’62, Carson to Valdespin in ’12. Wouldn’t it make more sense, he finally asked, to have the Mets in simple chronological order?

I believe he first made the suggestion years ago, in the middle innings of some dull affair during which something neglected at Shea Stadium broke and Jason Phillips did something inept. I don’t know that for sure, but it seems like a good bet on both accounts, and how best to organize binders full of old Mets cards is the kind of thing one logically turns to during such games.

My initial objection was that without play-by-play information for early games, I couldn’t figure out the true chronology. (And, really, you need pitch-by-pitch data.) But Retrosheet and Greg’s own digging took care of that one.

Then I argued that alphabetical order was important to being able to find someone, which we both knew wasn’t true. (Quick, what year was Nolan Ryan’s debut? Cleon Jones’s? Terry Leach’s?)

Finally, I quit dodging and offered the real reason: It made more sense, but it was just too much damn work.

But shortly before his 50th birthday, Greg sent along a massive Excel spreadsheet — there were the Mets, in perfect chronological order. And though he presumably didn’t know it, he’d caught me at the right time.

My kid is now 10. That means Joshua is old enough to be perform moderately delicate manual labor and keep track of a spreadsheet. Yet he’s too young to have an adult’s perspective on time and money — he thinks he has oceans of the former and he would like more of the latter. So I offered him a deal: $50 to convert The Holy Books to my co-writer’s long-desired format.

I also had a hidden agenda. Joshua is dangerously close to breaking up with the Mets, for which I can’t blame him: His favorite player was Jose Reyes, who won a batting title and was allowed to walk. He got interested in R.A. Dickey’s story, exulted when he won 20 and the Cy Young Award, and then … well, you know. The kid’s had it. We all have, except he’s 10 and he has other things to do with his life.

On the one hand, this is fine. When I turned 10, the Mets were two years into their nadir as the North Korea of the National League. I stuck it out for another year and half before walking away during the strike, and didn’t return until I started hearing about Straw and Keith and this amazing young pitcher named Dwight Gooden. That might not be too far removed from what will happen to this incarnation of the Mets. I survived it, finding my love of baseball and my team quick to rekindle.

On the other hand, it’s not fine at all. Joshua lives in a Mets house, and some of my fondest memories of parenthood have centered around him learning the game and the team and the players, both from me and from his mother. I don’t want to lose that and risk not getting it back amid the many distractions of busier-than-ever youth.

And so I thought this might help — a project that would double as a Mets history lesson.

We’ve worked side by side. I remove a year’s worth of cards. He puts them in chronological order. I read the Prince spreadsheet and he checks. He puts them back in the pages. I check again. And while we’re doing this, we talk Mets.

As you probably figured, revisiting the early years has been simultaneously exasperating and entertaining. Joshua’s early questions centered around whether such-and-such player had been good, and he grew a little perplexed at the fusillade of nos. Elio Chacon? No. Charley Neal? No. Gus Bell? Not any more. Jay Hook? No. Choo Choo Coleman? No. Harry Chiti? Goodness no.

But those nos had some amusing asterisks.

Elio Chacon wasn’t any good, but he also didn’t speak English and kept crashing into Richie Ashburn on pop-ups. So Richie learned how to say “I got it” in Spanish. It’s “Yo la tengo.” So there’s a pop-up, and Chacon runs out…

The Mets acquired Harry Chiti for a player to be named later. Harry Chiti proved so bad as a catcher that…

Richie Ashburn was actually pretty good. Good enough that he won a boat. Except Richie lived in Nebraska, and…

Jay Hook had studied engineering, and he could tell you why a curve ball curved. But…

The two Bob Millers aren’t the same person. There was Bob G. Miller and Bob L. Miller. The traveling secretary was worried how hotel switchboards would figure out which one a caller wanted. Then he had an idea…

Joe Pignatano came to the plate in the eighth inning of the final game of the ’62 season. He didn’t know it was the last at-bat of his career. There were two men on and nobody out…

And so on we’ve gone, through the Larry Burrights and Hawk Taylors and Danny Napoleons and Lou Klimchocks of the early Mets, leavened with questions about Gil Hodges and Yogi Berra and Warren Spahn and even the occasional flash of hope from Ron Hunt and Tug McGraw and Nolan Ryan and Tom Seaver. I’m not going to say it’s saving my kid’s fandom — that would be a lot to put on David Wright, let alone Joe Moock. But it’s been fun, and it’s been a bit of light in the darkness — and in a winter of greater-than-average discontent, I’ll take it.

Greg tells the Joe Pignatano story — and a whole lot more of them — in very entertaining style in Volume 1 of The Happiest Recap. Go get yourself one!

by Greg Prince on 1 January 2013 12:13 pm At 3:59 PM EST this afternoon, New York Mets baseball will step outside, see its own shadow and scurry back indoors for what will seem like another couple of centuries of winter, but fret not. It will be at that very moment that we have reached the Baseball Equinox, that juncture on the Spherical Horsehide Calendar when we are equidistant between the final out of the Mets’ 2012 season and the first pitch of the Mets’ 2013 season. Thus, when the clock strikes 4, it means we are (give or take a rain delay or ceremonial glitch) closer to next year than last year.

Hell, next year is this year now. And we can’t be stopped from having real, countable baseball inside it. The Mets have already prepared us for this great upturn in our fortunes by signing some dude from the American League to maybe pitch out of the bullpen and…well, they haven’t done much else yet that you don’t already know about, and what you know about remains up for grabs in the short and long terms…but isn’t knowing Opening Day will eventually get here with or without Aaron Laffey worth flipping away from the conclusion of the Capital One Bowl just to make sure you still get SNY?

Meanwhile, the Marlins are “willing to listen” to proposals for Giancarlo Stanton, which doesn’t necessarily mean the Mets have a prayer of landing him, but given the Marlins’ history of listening, it should at least guarantee we’re a lock to avoid fifth place.

See? This new year gets happier all the time.

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2012 2:24 pm It appears they let anybody turn 50 years old today. Even me.

As Sid Fernandez, Benny Agbayani, Rick Trlicek and a handful of others who — Trlicek-style — avoided distinguishing it could confirm, 50’s a number, just like any other number. Yet when you reach a number that’s considered enough of a milestone to rate commemorative-patch treatment, well, attention must be paid.

Goodness knows it got my attention the year I was 49 but barely noticed because I was laser-focused on turning 50. And now I have. It will take me a while to find out what the big deal is. I’m guessing it will sink in, so to speak, when my doctor tells me to make an appointment for one of those tests you get not because you’re ill but because you’re old. One year you’re 49 and wondering what’s up with Collin McHugh. The next year you’re 50 and you’re wondering what’s up with your colonoscopy. (And, probably, Collin McHugh.)

I’ll let those of you who are on the pre-Sid side of 50 in on a little secret. I’ve only been in my fifties for about half a day, but it’s not so bad to get here. That bit about “older and wiser”? It really does happen. I hit a spot in my mid-thirties when I realized how much I didn’t know about life. About a decade later, it began to dawn on me that I knew more than I realized and was learning more all the time. That’s not the same as saying I’ve figured out what to do with any of it, but, to borrow a phrase from another sport, I’m amazed sometimes how I’ve gained the ability to see the entire field. I understand “stuff” more than I ever have before. There’s plenty of stuff I don’t, but that’s part of the beauty of getting here, too. You know enough to know you don’t know everything and you know things you didn’t know you knew. You really start to put it together in your mind at some point.

Then nature apparently makes up for that great revelation by calculating ways to gradually chip away at that mind you’re so proud you’ve honed for a half-century. Plus going for those tests. And not really wanting to climb all the way to the top of Promenade if you can help it, though I’ve never been a big fan of that, anyway. There’s a tradeoff in there somewhere between wisdom absorbed and youth eroded. Like d’Arnaud for Dickey, a Mets fan can’t have everything at once.

Of course we’re all younger than we used to be if you follow the stereotypes associated with once ludicrously old-sounding ages like 40 and 50. My mother threw my father a surprise 50th birthday party 34 years ago next month. I was in charge of sending out the invitations from a store-bought pack whose cards said on the front, “Here’s Looking At You.” I decided to embellish what Hallmark or whoever printed by adding “Kid!” to the message…“Here’s Looking At You Kid!” I’d heard it on TV and, besides, as I understood it, middle-aged people loved being flattered at how young they seemed.

This did not go over well with my 49-year-old mother, who informed me with her usual understated approach to intrafamilial relations that these people whose invitations I had desecrated with my personal touch were, in terms Ben Franklin would use, the cream of their colonies.

They’re mature!

They’re distinguished!

They’re in business!

You don’t go around calling an adult “Kid!”

It’s an insult!

What kind of idiot are you?

From there followed the massive deployment of Liquid Paper to remove the offending passage. Moral crisis averted. Aesthetic disaster another story.

The party went on, as those mature, distinguished middle-aged people seemed frothy and uninsulted by the blotched-out “Kid!” while the whiskey sours and vodka tonics flowed. But they sure did seem older to me than I do to myself now. Times change. Social mores change. Commonly held values change. Technology changes (which is good, ’cause I’m pretty sure were low on Liquid Paper). Yet I’m still me, recognizable internally — prospective colonoscopy appointments notwithstanding — from 50 to when I was 16 and finding ways to allegedly ruin surprise parties that had nothing to do with ruining the surprise.

So either I don’t feel 50 or I do feel 50, because this — rambling recollections about the old days sprinkled with semi-superfluous Mets references — might very well be what 50 is…for this kid, at any rate.

Finally, per Ralph Kiner, happy birthday to all you new years out there.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2012 4:56 pm Just got out of HR. I was doing my exit interview with my forties. It was required as I’m leaving age 49 and starting my new position, in my fifties, at midnight.

HR asked me what I did with my forties, which officially began on December 31, 2002 and end tonight at 11:59 PM. I said I started a Mets blog with a friend of mine when I was 42 and I’ve enjoyed doing that a lot ever since.

Then HR asked me what else I did with the past ten years. I mentioned a few other Mets-related things, which led me into a tangent about some games I went to, some others I watched on TV and a bunch of people I got to know because of the Mets.

HR interrupted and asked if there was anything else I wanted to talk about from my forties, specifically anything that had absolutely nothing to do with the Mets.

I said no, not really.

And with that, HR made some notes in my file, shook my hand and wished me luck in my fifties.

So I guess that was it for the past decade of my life.

by Greg Prince on 29 December 2012 7:22 pm If four things don’t go exactly right Sunday, a team called the Giants will be done being defending champions. I’ll be sorry if/when they are eliminated from playoff contention, though mostly because a Super Bowl run is a great way to kill time en route to Spring Training. But while the halo above the New York Football Giants may be on the verge of vanishing, the San Francisco Baseball Giants can continue to winter in contentment as holders of the most super title of them all.

If I didn’t say it properly in late October — and I didn’t, really, given that my mind was on impending low-pressure systems and the havoc they were projected to wreak regionally — congratulations to the 2012 World Series champion San Francisco Giants, partly for their four-game sweep of the Detroit Tigers, more so for being so into each other as they prevailed.

Just got through watching the highlight film from the most recent Fall Classic (MLB Network + DVR = December Salvation) and was particularly taken by the togetherness the champion Giants evinced. They were playing for each other, they were loving each other, they were showering each other in heartfelt brotherhood as much as they were champagne. Hunter Pence, who’d been a Giant for about 10 minutes, had taken to firing up his teammates in the dugout prior to every game and it was a touching sight seeing something you only imagined working in movies working in real life. Marco Scutaro, also in his eleventh Giant minute, oozed affection for his temporary teammates. Angel Pagan, comparatively a Giant of McCoveyesque tenure, was reveling in everything San Franciscan: the players, the fans, the sourdough bread probably.

If it was the Braves or Cardinals or some even less appealing 2012 postseason agglomeration, these testimonials would rate the ceremonial sticking of the index finger down the symbolic throat, but the Giants really seemed to mean it. It was beautiful. Then again, why shouldn’t they be the teamiest team in all of teams? The results said they were the best team going.

Teams don’t always have to manfully embrace and pump each other up to find success, just as power and pitching aren’t personality-driven assets. But gosh darn it, it’s swell to connect good outcomes with good outlooks. I was particularly moved by this Giant view of the world since I had, not long before October, read Odd Man Out by Matt McCarthy, a reasonably engaging book from 2009 detailing a one-year minor league lefty’s experiences trying to make it at the lowest rung of professional baseball. Odd Man Out had its Ball Four behind-the-curtain charms, and the narrator — a young man who was fairly certain his future waited in medicine rather than on a mound — seemed sincere enough in his desire to share details of his season as a Provo Angel. But somewhere along the way, it veered from clever and insightful to just plain depressing.

McCarthy received not altogether flattering publicity when the book came out. His former teammates did not enjoy being portrayed as craven misanthropes all out for themselves (plus there was some question about the accuracy of his recollection of balls, strikes and whatnot). The author’s message was that in the low minors, everybody is essentially out for himself, which wasn’t all that surprising. There’s no loyalty to the Provo Angels, per se. The idea is to get the attention of the organization and advance to the next level and the one after that. If someone else on your team is succeeding, it doesn’t help you one iota. The minors aren’t like high school or college. They’re a business. Cynicism trumps innocence, home and away.

I suppose I knew that, but I didn’t enjoy having it confirmed from the inside. Hence, watching the 2012 World Series film and being reminded that the certified best professional baseball team of the past year behaved in a manner 180 degrees opposite was downright heartwarming. To play like a champion in San Francisco meant checking divisiveness at the door and being one for all/all for one. Giants fans likely wouldn’t welcome even a vague comparison to something smacking of Los Angeles, but their plotline was pretty Hollywood in the end. You had these well-compensated holdovers and you had these well-compensated acquisitions, except nobody acted like a mercenary and nobody seemed to be in it solely for himself. Maybe it’s easy to exude togetherness when you finish first, but when the fourth game was over and the trophy was awarded, I really bought the fairy-tale ending.

The 2012 World Series film is, after all, a documentary.

If you want to listen to some Metsian togetherness, check out the Gal for All Seasons podcast that features Faith, Fear and Coop!

by Greg Prince on 27 December 2012 2:57 pm Contrary to the tiresome claims every modern-day sportswriter makes about rooting for stories over teams and having no rooting interest otherwise, Oscar Madison of the New York Herald clearly had a favorite ballclub. If he didn’t wear his heart on his sleeve or in his widely read columns, his allegiance was evident on his head. We could read who Oscar loved by reading Oscar’s cap…a Mets cap.

The cap said it best, though when we had the opportunity to listen in on Oscar’s conversations, whether with his fussy roommate Felix Unger (a talented photographer, portraits a specialty, who didn’t seem to much care about sports) or anybody else, we would hear the Mets come up occasionally as well.

He might tell a Little Brother he and Felix were mentoring that he — Oscar Madison, a columnist and not a coach — taught Tom Seaver how to throw a curveball.

He might lament to Felix that he never aspired to own the Mets as much as he did a racehorse, but would settle for this sleek greyhound named Golden Earrings (which was all well and good, unless you lived at 1049 Central Park West, which didn’t necessarily seem like an ideal kennel for the pup, no matter the shape of Oscar’s room).

And like anybody who loves the Mets, he could be brutally honest about their failings. He went on his short-lived radio show, Oscar Madison Talking Sports, and felt compelled to criticize the team. Things got so heated that a couple of Mets fans came to his apartment and expressed their displeasure with his analysis the best way Mets fans knew how before Twitter: by swatting him with their caps.

Yet with true verve and panache (to borrow a phrase found in one of Oscar’s rare theatrical reviews…well, it ran under his byline, at any rate), Oscar kept his Mets cap on around the house, kept a Mets pennant hanging limply from his wall and even framed a photograph of Wes Westrum for inspiration. Oscar was so matter-of-fact about his affinity for the Mets, that it got to a point where you almost didn’t notice it.

But years later, as the news has come down that Oscar Madison has, regrettably, finally accepted his buyout package from the Herald, we pause to properly tip our cap to Oscar’s cap. We appreciate that he wore it so regularly and so jauntily — particularly from 1970 to 1975 — that he made it seem natural. We looked at Oscar’s cap and thought, almost without thinking about it, that yes, of course, a Mets cap…why wouldn’t a person wear one of those? Oscar made the Mets cap so much a part of the landscape that not wearing one is what would’ve made a person look like an oddball.

Oscar wasn’t odd. He was ours. And as we dig out his old columns and marvel at his versatility (did you know he once organized a wrestling match that fostered better Sino-American relations?) let alone his flair for living (when not chronicling sports from his living room typewriter, he followed his gourmet muse to create the nouvelle cuisine dish goop melange), we honor him by inaugurating a new Faith and Fear in Flushing accolade in his name.

It is called the Oscar’s Cap, and it is given annually — starting now — to those shining examples in the concluding year’s popular culture anywhere the New York Mets played a featured or supporting role. Oscar’s Caps are awarded in film, television, music, theater, literature…any medium we come across in 2012 where we weren’t expecting the Mets to appear…yet they did.

There are two categories of Oscar’s Caps: Contemporary — given to those works that appeared on the popular culture horizon for the first time during the year in question; and Retro — given to those works that were created in the recent or distant past but, for whatever reason, came to our attention for the first time during the year in question. Essentially, we had to suddenly see something about the Mets or hear something about the Mets or notice something about the Mets or be clued into something about the Mets pertaining to their presence within the popular culture from before 2012. Why we didn’t know about those appearances and incidences before 2012 and only stumbled into them over the past twelve months is hard to fathom, but as we’re often busy thinking about the Mets in the sporting culture, we can’t necessarily catch everything the first time around in the popular culture.

That, after all, is why they sometimes run repeats of the best stuff into perpetuity.

In the realm of Contemporary Popular Culture, 2012 Oscar’s Caps are awarded to the following:

• ABC’s The Middle, which used vintage footage of Shea Stadium under construction to help evoke mom Frankie Heck’s excitement that Super Bowl XLVI was coming to Indianapolis, not far from the Hecks’ home in Orson, Indiana.

• The Broadway revival of On A Clear Day You Can See Forever, whose penultimate musical number, “Come Back To Me,” includes the lyrics “Don’t get lost at Korvette’s/Or get signed by the Mets.”

• NBC’s 30 Rock, whose guest stars included Mr. Met in two episodes (“The Tuxedo Begins” and “Meet the Woggels”) and which dressed a wedding party in 7 Line gear because Mets t-shirts are what the bride and groom told Liz Lemon they were wearing “when we Met”.

• John Grisham’s novel, Calico Joe, whose title character, 1973 Chicago Cubs first baseman Joe Castle, gains a fan in Paul Tracey, “the young son of a hard-partying and hard-throwing Mets pitcher” named Warren Tracey.

• The film Men In Black 3, in which Griffin watches the final out of the 1969 World Series unfold and explains to Agent J and Agent K that “this is my favorite moment in human history,” for “a miracle is what is not possible but happens anyway.”

• DJ White Owl’s “Kings From Queens,” a name-checking, hip-hop ode to the 1986 Mets that recalls the days “before Johan threw that no-hit game/before David Wright brought the Mets that fame/before Citi Field, Ike Davis, Jason Bay/we were glued to the tube watching every double play.”

• Joshua Henkin’s novel, The World Without You, whose characters include Lily, a Mets fan since 1986 who “has no patience for Yankees fans, especially the newly minted New Yorkers, the arrivistes,” and a dog named Kingman.

• Wayne Wilentz’s jazz piano composition, “A Song With Orange And Blue,” a 50th-anniversary musical tribute that swears “It’s no lie/Tommie Agee could fly” and celebrates (among others) “Choo Choo and Charlie/Valentine, Darling/the Hammer, the Doc and the Straw.”

• HBO’s The Newsroom, whose senior producer, Jim Harper, spends a portion of a Sunday night party watching the Mets-Phillies game of May 1, 2011, on his laptop, before word leaks that Osama Bin Laden’s been killed; later, ACN executive Reese Lansing admonishes News Night’s brain trust that the show’s ratings have tumbled “from second to fifth place in the course of five days, a feat I previously thought was only accomplishable by the New York Mets.”

• CBS’s Elementary, whose Dr. Joan Watson is a Mets fan who won’t go out until she sees the outcome of a Mets-Reds game that has reached the ninth inning, despite being informed by Sherlock Holmes that, based on all available evidence, the Mets will lose, 3-2.

• Fox’s The Simpsons, whose titular family’s trip to the Big Apple is advocated by Bart, who informs Homer, “But you love New York now that your least favorite buildings have been obliterated: old Penn Station and Shea Stadium!” (to which Homer shakes his fist and grumbles, “lousy outdated relics…”); later in 2012, Homer downloads the Lenny Dykstra’s Prison Break app to his MyPad.

• ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live, which portrayed “young Jimmy Kimmel” in a Mets t-shirt in a flashback exploring the late-night host’s Brooklyn upbringing.

• NBC’s Saturday Night Live, whose Fox and Friends segment included a slew of on-screen “corrections” that rolled by rapidly, including one that made clear “Mr. Met has never announced a preference for any religion over the other”; earlier in 2012, SNL aired a commercial for the Charles Barkley Postgame Translator App, which translated David Wright’s benign thoughts regarding a tough loss to “I don’t know why they’re celebrating beating the Mets — everybody beats us!”

• Fox’s The Mindy Project, on which Dr. Danny Castellano has on his office wall a framed, matted portrait of Shea Stadium.

• Adam Sandler, who, during the 12-12-12 concert that raised funds to aid victims of Superstorm Sandy, reworked the lyrics to Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” to include his selective-memory assessment that “the Mets have sucked since ’86”.

Finally, though his Mets commentary is generally unscripted and presented outside the realm of fiction, the 2012 Oscar’s Cap of Lifetime Achievement is awarded to Jon Stewart, host of The Daily Show in recognition of his long having used his news & entertainment platform to articulate true Mets fan angst. Stewart’s work was best exemplified in his December 4 interview of R.A. Dickey, when Stewart asked his Cy Young-winning guest — who was then in protracted contract negotiations with the team — “How will the New York Mets screw this up?”

In the realm of Retro Popular Culture, 2012 Oscar’s Caps are awarded to the following:

• Any Wednesday, the 1966 film in which John Cleves (Jason Robards) and Ellen Gordon (Jane Fonda) are engaging in an extramarital affair and seeking a discrete night out. Ellen suggests, “Hey, you know what’d be fun? We could go to the Shea Stadium. The Mets are in town!” but John rebuffs her because he and his wife “had a season’s box right behind the dugout. The Mets shock easy.”

• East Side, West Side, the 1963-64 George C. Scott inner city drama on which Mets catcher Jesse Gonder hit fungoes to kids.

• Friends With Benefits, the 2011 romantic comedy romp during which a televised Jose Reyes home run at Citi Field and a 2010 “WE BELIEVE” pay phone advertisement featuring “ACE” Johan Santana appear.

• Bye Bye Braverman, the 1968 comic drama that yielded a couple of shots of Shea Stadium and World’s Fair relics in the background of scenes filmed at Cedar Grove Cemetery off the Long Island Expressway.

• Lawrence Block’s 2011 anthology, The Night and the Music, wherein Matt Scudder takes kids to a Mets game; Jon Matlack is rocked and the Mets lose, 13-4.

• Car 54, Where Are You?, which gave the Mets quite possibly their first pop culture mention when, on October 8, 1961, Officer Toody’s small talk that “they’re tearing down the Met” is answered by Officer Schnauzer’s rejoinder, “The new ballclub? They haven’t even played a game yet!”

• Pom Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold, Morgan Spurlock’s 2011 documentary on product placement, which includes Citi Field in a montage of stadiums and arenas that are named for corporate sponsors.

• Paul Auster’s 1985 novel, City of Glass, which contains characters who discuss Dave Kingman and George Foster; its protagonist, Quinn, works under the pseudonym William Wilson and comes to realize that his fictional name is the same as the actual name of “promising young player” Mookie Wilson.

• Mo’ Better Blues, Spike Lee’s 1990 jazz-inflected drama, which features Giant (Lee), who bets against the Mets in the September 29, 1989 doubleheader versus the Pirates because “the Mets need some more black ballplayers” (the Mets swept both games); there is also a lengthy flashback scene that takes place on September 20, 1969, when Giant’s dad is watching Rod Gaspar bat against Bob Moose at Shea Stadium (Bob Murphy’s call of the eventual no-hitter is audible).

• Moscow On The Hudson, the 1984 Robin Williams vehicle in which Vladimir Ivanoff (Williams) meets a fellow Soviet defector who now sells hot dogs on the streets of Manhattan while wearing a Mets cap.

• Youth-leaning variety program Hullabaloo, during which, on April 4, 1966, Soupy Sales and his sons Hunt and Tony sang a rollicking version of “Meet The Mets”.

• Married To It, the 1991 film that attempted to explore the perils of matrimony through the eyes of three couples whose attempt to identify “the best day of the ’60s” led Leo Rothenberg (Ron Silver) to insist, “No contest. October 16, 1969, bottom of the ninth, Davey Johnson batting for the Orioles…” Leo and the other two husbands (played by Beau Bridges and Robert Sean Leonard) transition at once into reciting play-by-play details of Johnson’s fly ball to Cleon Jones, who catches it for the final out of the World Series — an event labeled in 2012’s Men In Black 3, it is worth reiterating, as at least one space alien’s “favorite moment in human history”.

Special thanks to Faith and Fear readers, Hofstra 50th Anniversary conference attendees and Crane Pool Forum compatriots for their help in compiling the 2012 Mets Pop Culture Review. And appreciation always to Jack Klugman for immortalizing Oscar Madison.

by Greg Prince on 25 December 2012 10:30 pm Ike Davis…he was at that Mets holiday party a couple of weeks ago, too. His attendance got kind of lost in the shuffle given the kerfuffle that was kicked up by the remarks of his (now erstwhile) teammate, but Ike’s presence at Citi Field on December 11 was both comforting and intriguing for several reasons.

First of all, Ike, like R.A. Dickey, modeled the new Mets uniform top. That’s three consecutive offseasons that Ike’s employer summoned him to the ballpark to try on something the Mets had never worn before. In December 2010, it was the dubious cream pinstripes; in November 2011, he donned the throwback traditional pins; this time around, it was the blue alternates. When it comes to team apparel, Ike Davis is turning into Matthew McConaughey’s Wooderson from Dazed and Confused — he gets older, those crisp, new, marketable uniforms stay the same age.

Not that long ago, Davis wasn’t necessarily a sure thing to remain a Hot Stove staple at Mets events. There were murmurs that indicated the Mets weren’t happy with Ike personally (not to be confused with the shouts that indicate Mets fans aren’t happy with the Mets professionally). These were reported around the same time Ike had revived his power stroke and was doing charitable work close to his heart. Yet somebody connected to the Mets murmured, as those connected to the Mets inevitably will.

Come December, the Mets found a higher-profile player to murmur their unhappiness about, and now that guy’s gone. But Ike’s still here, still modeling the latest in jerseys and still affably answering any innocuous question any curious person might ask to fill the time between baseball seasons. He even politely (if a little icily) answered the stringer from somewhere who asked him, “Can you talk about the contract you just signed that made you a Met for life?”

“That’s not me,” Ike informed the guy who assumed all Met infielders look alike.

Identity crises aside, that’s what the press portion of the holiday party was supposed to be: innocuous as the winter is long. We don’t really care about how Ike Davis is preparing for Spring Training. We just want to be reassured that he is preparing for Spring Training, that there will be Spring Training, that there will be spring; and that when spring returns, baseball players will greet it and us in full uniforms. Nobody gives a good gosh-darn over when Ike’s going to begin swinging in the cage. Merely having a reason to use phrases like “swinging in the cage” in December is motivation enough to gather ballplayers and the ball-curious in one room.

Ask ball. Talk ball. Write ball. Is it spring yet?

None of what Davis said was remotely newsworthy. He offered about a dozen Met-a culpas for having hit so far below .200 for so much of 2012 before recovering in the second half to achieve a homer-laden .227. “Guys,” he told those of us who weren’t off filing breathless Dickey dispatches, “I can’t play any worse.” When pressed as to why he clung so stubbornly to the Interstate for so long, Ike traced it to coming back from the injury that sidelined him most of 2011. Thirteen months earlier, we were surrounding Ike and asking with genuine curiosity about what Spring Training would be like for him and his out-of-action ankle. This time around, reflection on what went wrong was the order of Davis’s day.

“I lost the rhythm of the game,” he admitted, explaining that because he couldn’t play, couldn’t run, couldn’t do anything for months on end, it took a temporary toll on his abilities. That was an answer I found intriguing, so I followed up by asking how that worked exactly — you’ve been playing baseball your whole life, yet you can just sort of forget how after an extended layoff?

Well, yeah, he replied. “If you stop using your brain for six months,” he reasoned, “you probably wouldn’t be as smart.”

Maybe that was the problem for that stringer who mistook Ike Davis for David Wright. And maybe that was very much the problem for a first baseman whose body betrayed him when he was batting .302 on May 10, 2011, yet found himself wallowing at .160 on June 5, 2012. Perhaps baseball instinct, which might have been what I was thinking of as I attempted to use my brain to understand Davis’s explanation, shouldn’t be confused with baseball rhythm. I’m guessing he still knew how to hit but just didn’t know how to unlock the groove that would allow him to hit consistently.

Baseball fandom shouldn’t be confused with baseball playing, but maybe we don’t always have our rhythm, either. Sometimes we keep rooting harder and harder, even if we aren’t doing our team any good. Sometimes we just need a blow…particularly when blowing is exactly what our team has been doing for days on end.

I had an afternoon like that last summer, which seems ridiculous when it’s late in December and you’d kill for 80 degrees and a six-game homestand, but that sounds better in absentia than in reality. It was plenty warm this past July 25, but the Mets were ice cold. They had come out of the All-Star break losing five of six on the road. They returned to Flushing and got worse: swept three by Los Angeles, three more by Washington. They were on a 1-12 skein, their once-promising postseason bid was in tatters and the thought of sitting at my computer and stewing over their state was stifling.

I had to get away from the Mets. I had to go to my happy place. I had to go to Babylon.

I imagine every small town potentially looks like something special when you don’t live in it. For example, I don’t live in the village of Babylon, but I’ve come to think of it as something special. The place never pierced my consciousness until sometime in the 1990s when it was the subject of a relentless Long Island cable TV ad campaign urging investment within its township’s borders because “the heart of it all has it all…Babylon!”

It was an annoying as all get-out jingle, but it planted itself in my head in the same era that our adorable cat Casey was making himself at home in our hearts and on our laps and amid any personal space he could successfully infiltrate. Somehow, the way these things will, “the heart of it all…” morphed into my repeated pronouncements that, as Casey leapt into and onto us, our tabby was determined to be “a part of it all”. So, for a time, the concept of Babylon and the actuality of Casey merged into one.

Not everybody would derive such pleasant associations from the Babylon Industrial Development Association’s imagemaking efforts. Upon Googling “Babylon” and “the heart of it all has it all,” I found this 2004 LiveJournal take on the theme and the township in general from “James,” someone who grew up there in the ’90s:

“fuck babylon, the heart of it all has it all babylon = bullshit, go step in some goose shit.”

I’ll defer to “James,” who is not incorrect about the geese as far as I can tell, on his hometown’s full-time drawbacks. The heart of the village of Babylon is Argyle Lake Park and it is indeed unfortunately a magnet for Canada Geese and all they leave behind. Step lively as you walk is our advice should you decide to do what we did a few years ago and visit the heart of it all.

Other than that, we found nothing we didn’t like there.

Stephanie hatched the idea of exploring Babylon based on nothing much more than our LIRR line is the Babylon line. We board well west of its eastern terminus, and always head west — for Manhattan, for Woodside, for a transfer to what is now known as Mets-Willets Point — but she got to thinking, with a few days off ahead of her in 2009, that there must be something out there we don’t know about. So we decided to hop on one of those eastbound trains and find out for ourselves.

In the ensuing years, Babylon became something special, geese population notwithstanding. We’ve returned annually for a few hours at a time and have discovered something besides the charming downtown and the shimmering lake and the grassy park and the handy proximity to commuter transit that made us recurring visitors.

We keep coming back for the baseball — even on a day like the last Wednesday of July 2012 when I was pretty sure I was seeking out Babylon as a refuge from baseball.

Funny how that works. Stephanie was again off for a few days and had suggested we go to the game the night before. Of course I said yes. Of course it was a sweet time that Tuesday night. It always is when we go. We landed StubHub Field Level seats in right for what was already a looming Cy Young matchup between Dickey and Gio Gonzalez. For a while, it lived up to its billing. Then it went predictably to hell, but these were the Mets at home in the latter portion of July 2012, so it was bound to.

Sweet time, nonetheless. Whenever the Mets did something wrong, one or the other of us would groan, “c’mon…METS,” like the voice actress in the radio commercials that were airing constantly all summer long, the ones opposing Mayor Bloomberg’s bizarre beverage cup-size regulations (the lady was supposed to be a “real” New Yorker from Queens expressing her freedom of choice). Repetition on the radio made those commercials more and more grating, but “c’mon…METS,” sprinkled throughout the evening’s setbacks made a progressively worse 5-2 defeat incrementally more tolerable.

Sweet, fun, aggravating: The Mets game, July 24, 2012. The kids from Camp Simcha in the Big Apple seats needed no such diversions. They were diversion enough as was. They dressed in blue yet were not at all blue about their situation (Camp Simcha caters to children stricken by serious illness) nor that of the Mets. They roared the national anthem. They waved lengthy balloons. They cheered their heads off for the home team. The Mets lost that Tuesday night. The kids from Camp Simcha betrayed no sense they were anything but winners.

What else? Well, there was, for the first time that I had noticed, a special R.A.-DICULOUS foam finger for sale, an item that got a vigorous workout from someone sitting to our left.

There was a woman in a THOLE 30 shirt sitting in front of us, also a Citi Field first by my reckoning.

There was Justin Turner walking to the plate to Carly Rae Jepsen, which somehow made him less endearing than it should have.

There was a low din of muttering for Jason Bay, no matter how much we told ourselves he hustles.

There was boorish booing directed toward Bryce Harper, which seemed premature, but why wait for a superstar-in-the-making to give us a good reason for bad behavior?

There was a moment of ultimately hollow excitement when Jordany Valdespin hit the pinch-homer that did little to alter the competitive trajectory of the game but set a team record for most pinch-homers in a season (it would be his last such shot of the year, though not because he slugged his way into the starting lineup).

There was even a John Franco sighting bordering our section, which was not the playground of big shots by any means. A guy who looked like he’s usually sipping cappuccino outside the pork store sashayed down the stairs. “Hey, isn’t that…?” Indeed it was: Johnny from Bensonhurst, slipping into an empty seat and whispering into the ear of an acquaintance. Moments later, the two of them were off to presumably ritzier accommodations (or to take care of that thing).

Wow! New York Mets Hall of Famer John Franco comes down to where the common folk sit to touch base with his buddy! I would’ve thought they had people for that. I was also surprised security let him pass. Imagine that conversation:

“Excuse me, sir, I need to see your ticket.”

“Oh, I’ll just be a second. I’m lookin’ for my friend.”

“I’m sorry, sir. You need a ticket for this section.”

“But I’m John Franco! I’m in the Mets Hall of Fame!”

“I’m sorry, sir, but I don’t know what that is.”

Fun, extracted from aggravation. The Mets lost their fifth in a row that Tuesday night. Then Wednesday afternoon they lost their sixth in a row. More aggravation. Thole, whose game-calling abilities had been vaguely grumbled at by a second dissatisfied reliever in a week’s time (first Pedro Beato, then Tim Byrdak), summed up the homestand’s vibe best when it was over. “I don’t think anything can get any worse than it is right now,” the catcher confessed. “We can’t wait to get out of here.”

Josh wasn’t demanding a trade to Toronto as far as he knew, and I’m guessing he wasn’t ready to renounce his affiliation let alone his profession. He just needed a blow or a chance to rediscover his rhythm or hone his instinct anew…he surely needed something. In Thole’s and his overwrought teammates’ case, they received a flight to Phoenix and an encouraging shot in the arm from a 23-year-old rookie making his 11-strikeout major league debut Thursday night. Not a bad way to break in and not a bad way to forget the perils of stubbornly inedible home cooking.

As for me, 24+ hours before Matt Harvey hinted that being a Mets fan might eventually be more fun than aggravating again, the remedy was backing away from my virtual home field online and jumping on that train to Babylon with my wife so we could enjoy an evening physically far from where I spend too much time thinking about the Mets. Our goal was technically a nice walk and a nice dinner in a picturesque town that had yet to be touched by a scourge named Sandy. We were not explicitly getting away from the Mets and baseball, but it sure felt good to do just that for a spell.

Looking up to the man who built us a home, November 13, 2011. Yet you know what we did while on the lam from the Mets and baseball? We sought out reminders of the Mets and baseball. That’s what we do every time we’re in Babylon. We get off the train, amble up Deer Park Avenue, hang a right onto Main Street and mosey over to Robert Moses. Moses lived in Babylon and they erected an impressive statue of him in memoriam. Moses, as I’ve been acutely aware ever since I devoured The Power Broker, conceived and constructed modern New York. He was simultaneously the best and worst thing that ever happened to this region, as Robert Caro explained across 1,344 absorbing pages. But mostly, for our purposes, he built Shea Stadium. He built the park that encompassed Shea Stadium. He built the roads that led to Shea Stadium.

And who among us wouldn’t have argued that between 1964 and 2008, all roads led to Shea Stadium?

Hence, when we go to Babylon and I make sure I stop by the Robert Moses statue to pay homage to, when you get right down to it, baseball. Then we resume our walk, heading to Argyle Lake Park (goose droppings be damned) and we track down another monument, one we might have missed had we not known to be on the lookout for it. It’s the understated memorial set up a couple of years ago that marks the spot where the Cuban Giants played. The Cuban Giants were not really from Cuba. They were the first professional black baseball team; their roster was comprised of the staff of the Argyle Hotel, a local landmark that once stood approximately where we did in July.

That was in 1885, or 62 years before the so-called big leagues deigned to allow within its hallowed ranks a professional baseball player whose skin was a different color from everybody else’s on the diamond. Robert Moses’s life work may rightly be construed as a mixture of sublime and reprehensible, and you may legitimately wonder if a heroic statue is appropriate for the man who could be said to have destroyed as much as he built. But the circumstances that demanded the Cuban Giants and the myriad Negro League teams that would follow in their footsteps — 18 of them using the name “Giants” by one count — are not up for debate. Those were just plain vile. That’s not a baseball story. That’s an American story. And baseball is American as it gets in our estimation.

A group of people loved playing baseball more than they couldn’t stand being treated as something less than fully American…and they did it in Babylon, a half-hour train ride from where we live. Thus, in the summer of 2012, it became imperative that we seek out their marker and bestow upon its sliver of earth a small, belated token of our appreciation: a current New York Mets pocket schedule, of which I’m almost always carrying a few. I planted it into the specially designated grass of Argyle Lake Park as my way of saying, in essence, “You guys were big league in every way that mattered.”

Small big league tribute, July 25, 2012. Then we continued our walk through that beautiful park, which sits next to Babylon High School, which wasn’t open on a summer evening, but there was something going on there nonetheless. It was a baseball game. I didn’t know the league. I didn’t catch the names of the teams. I could only guess the ages of the participants. And we were only on hand for the final out and rote handshakes that followed (though I did overhear one of the coaches exhort his players to keep doing more of what worked, leading me to wonder how effective motivational speeches really are). But I was delighted to have encountered real, live baseball. We had paid two private historical tributes — to Moses, to the Cuban Giants — but now we got the real thing, if just a taste. We got living, breathing baseball, a guarantee that this game we love goes on and on.

Longer than it took America to ascend from tacitly sanctioning black teams and white teams to having just teams.

Longer than it’s taken Robert Caro to profile Lyndon Johnson in full.

Longer than a six-game losing streak even, despite the irrefutable fact that those feel like they’re never gonna end.

The game goes on, July 25, 2012. That’s when, as we walked on toward our nice dinner at the Argyle Grill & Tavern (where they serve an enchanting ale named for the causeway that was named for the man who built Shea Stadium), I realized I’m hopelessly incapable of getting away from baseball. I always find it and it always finds me. Months later, on Christmas night, no matter what Ike Davis tried to tell me about sustained periods of inactivity, I’ve got my baseball rhythm.

Who could ask for anything more?

by Greg Prince on 22 December 2012 1:25 pm 1. “And at Christmas, you tell the truth,” or so I heard it said in Love, Actually.

2. But I’m still seeking the truth in the trade that has left us Dickeyless in New York City.

3. Is it true somehow that sending away our singular Cy Young recipient was the brilliant Aldersonian chess move for which we’ve all been waiting two years?

4. I’m not trying to bait anyone or restart the same debate that dominated the week in Metsdom.

5. It’s more a rhetorical question, as we cannot know the answer just yet.

6. I admire the element of sophistication in those who see its brilliance.

7. And in a phrase I’ve heard repeated over and over again since Monday, I get it.

8. I get the potential payoff, I get the straits this organization has been in for too long, I get who was most likely to bring long-term value as a trading chip.

9. Still, though, I can’t quite say “yay!” to all that, because we just traded 20-6, 2.73, 230, 233.7, 1.053…and those are just the spectacular numbers.

10. That leaves aside the spectacular persona, which, when woven amid those award-winning statistics, gave us that rara avis known as the One and Only.

11. There was the One and Only R.A. Dickey, he pitched for our team, and our team told him to go pitch in another country.

12. But I get it — or I hope to at some point between 2013 and 2016 when Travis d’Arnaud, Noah Syndergaard and perhaps Wuilmer Becerra develop, emerge and become intrinsic cogs in the next Met juggernaut.

13. I don’t need a litany of the Met prospects who misfired; I can name them myself.

14. I want to believe in these kids whom I’ve never seen and until recently I had never heard of.

15. I want to believe the outfielder will fill one of those holes that’s never more than patched up; that the pitcher will throw hard, consistently, elusively and for a long time; and that the catcher is the catcher he’s been billed as during his six-year climb through the minor leagues.

16. By the way, what does Travis d’Arnaud have to be to have been worth it?

17. It’s probably too much to ask that someone who’s been coming along kind of slowly in the minor leagues (having suffered a couple of ascent-slowing injuries) to step up and become Buster Posey, but will we settle for something within the realm of John Stearns?

18. This trade defies easy historical parallels, but the one that comes closest in my mind is the one that, in essence, sent a franchise icon named Tug McGraw to Philadelphia for a stud catching prospect named John Stearns.

19. McGraw wasn’t at the top of his game when the trade was made in December 1974, but he would eventually recover his form and do great things for his new team, most notably record the final out of their first World Series championship six year later.

20. Stearns, who served the Mets from 1975 to 1984, never led his new team to the heights of its profession, but when healthy, he filled his position admirably and played the game passionately.

21. Would we be satisfied if d’Arnaud produces more like a Stearns than a Posey?

22. We’ve just limped through five seasons of Brian Schneider, Ramon Castro, Robinson Cancel, Omir Santos, Rod Barajas, Henry Blanco, Ronny Paulino, Rob Johnson, Kelly Shoppach, Mike Nickeas and, most disappointingly, Josh Thole (entombed with his Pharaoh so as to catch him in the afterlife), each of whom gave us a moment or two or glory, none of whom left us very comfortable with catcher on a long-term basis.

23. The second coming of John Stearns would be a dream by comparison, but Stearns wasn’t the catcher of his era by any means.

24. Not that d’Arnaud (originally, like Stearns, a first-round pick of those Phillies) is necessarily The Dude Reincarnate or, for that matter, a Grote or Hundley, but it’s probably too much to ask for a Posey, never mind a Piazza.

25. Dickey, on the other hand, almost always delivered everything for which he was asked, including honest answers.

26. I bring that up because, as mentioned previously, I was at what turned out to be R.A.’s final Met appearance, at the now infamous kids holiday party, and I want to reiterate what happened there.

27. Dickey headed into the main dining room with Ike Davis; he was greeted warmly by the Mets’ guests; then he was brought behind a curtained-off area to meet the media corps the Mets invited.

28. The press had one line of questioning on its mind and it expressed it without hesistation: “What about your contract negotiations?”

29. Dickey started answering and kept answering as long as he was asked.

30. No children were harmed during the Q&A portion of the morning — it was all out of view and out of earshot of the children from Far Rockaway.

31. Whatever R.A.’s perceived agenda, there would have been a small riot among the reporters and camera people who were at Citi Field solely to get R.A.’s thoughts had he brushed off their inquiries.

32. The kids kept on with their toys and their brunch, not at all scandalized, and one of them (a little girl whose picture I tried to take but she quite reasonably jumped for joy when Mr. Met entered the scene) wound up with the blue DICKEY 43 jersey he wore briefly.

33. Any other criticisms of Dickey as self-promoter or unpopular teammate strike me as sudden, shallow and opportunistic, and those who level them reveal the perils of being paid to write frequently when they have nothing of value to add to the overall baseball conversation.

34. Dickey, meanwhile, goes out on top, not just by performance but in esteem.

35. Although three years of R.A. Dickey as a New York Met don’t seem like enough, it might be that we had him for the perfect time span emotionally.

36. There are a bunch of relatively high-profile Mets who spent parts or all of three seasons here who, historically speaking, stayed just long enough to make an everlasting positive impression but not so long as to wear out their welcome.

37. Three-year Mets include Rod Kanehl, Ed Charles, Donn Clendenon, Ray Knight, Rico Brogna, John Olerud, Robin Ventura and now R.A. Dickey; all are remembered eternally fondly and none was burdened in real time by gripes about uselessness or contracts and none was subject to the kind of selective “what have you done for us lately?” amnesia we tend to inflict on our icons when they dare to be more enduring than fleeting.

38. Dickey also replaces the likes of Kanehl and Brogna and anybody you’d care to name who played for the Mets exclusively in the “pantheon” of seasons that include only 1962-1968; 1974; 1977-1983; 1991-1996; 2002-2004; and 2009-2012.

39. That is to say R.A. Dickey was surely the best Met never to play on a Mets team that compiled a winning record.

40. That’s an unfortunate distinction, of course.

41. And it helps explain, as painful as I’ve found thinking about it this week, why it helps to be sophisticated about the trade that cost us (to borrow a phrase Roger Angell applied to Tom Seaver upon his 1977 forced departure from New York) our sunlit prominence.

42. I will deeply miss writing about R.A. Dickey in the present tense, but I hated the “he’s the only good thing about this team” context that pervaded so many of those dispatches, and it is my fondest Mets wish that this transaction changes the context dramatically.

43. And that’s my truth this Christmas.

by Greg Prince on 18 December 2012 10:00 am  Final impressions, from the Mets’ 2012 holiday party at Citi Field. “How does Alderson go about reviving the more dormant aspects of our passion, those which have been dulled by two years of dismal sputtering on the heels of two years of dramatic letdown? By winning, of course. Winning will make us all feel better. Winning will bring new iconicism to the uniform, to the franchise and to our self-esteem. Seats will not go unfilled when we’re winning. Enthusiasm won’t need to be cultivated. It will emerge and it will roar the way it once did in these parts. And how does Alderson get us to that point? That’s the more difficult question, and for all the broad strokes (and narrow beseechments) we are all willing to offer, the only person who is entrusted to answer it is Sandy Alderson. That’s why they’re paying the man. But if he doesn’t mind a touch of fan interference, I’d be willing to remove a potentially perceived obstacle from his thinking. Explore every trade that makes sense to you and, if you are convinced in your role as our grand baseball poobah that it’s the right thing to do, trade anybody you feel you have to trade. Your job is improving the New York Mets. There are no sacred cows grazing in Citi Field. Not after 2010. Not after 2009.”

—A relatively typical Mets fan, October 29, 2010

“While your lead character R.A. Dickey is richly drawn, and his backstory is potentially appealing, we here at Limited Imagination agree there is no way he could exist. Since you insist on setting Dickey within the milieu of major league baseball, there needs to be at least some semblance of reality attached to your protagonist, and quite frankly, your Dickey may be the least fathomable sports character we’ve ever read. According to our research department, most successful baseball pitchers attain a level of peak performance in their 20s, but your Dickey is supposedly a career journeyman derailed by the lack of an essential component in his throwing arm who attempts to learn a magic pitch in his 30s, takes years to master it and then, quite suddenly, takes it to a whole other level where he becomes all but impossible to hit. The sports reader may ‘root’ for the unexpected, but that demographic is more and more grounded in statistical probability and the Dickey you describe in the latter chapters begins to do things that sound impossible. We could accept a certain literary license in making Dickey fairly articulate as a contrast to the usual ballplayer, but having him write a searing memoir that lands on the New York Times bestseller list in advance of creating this pitching alchemy again stretches credulity.”

—“Clueless Editor,” rejecting book proposal from “George Plimpton,” following the events of June 13, 2012

“It was a blast to be in R.A.’s ranks Thursday. I’d practically call it an honor to bear witness to the sixth Mets pitcher clinching the ninth 20-win season in franchise history. Every fifth or sixth day in the second half of 2012, R.A. lifted us from the benign disengagement you’d rightly infer a fourth-place team inspires to full-fledged immersion that seemed perfectly logical as Dickey’s knucklers rode their own private highway from his well-traveled fingertips to Josh Thole’s oversized mitt. It’s a shame his 20th win didn’t come in service to a better Mets team, but it was enough, I suppose, that R.A. Dickey made the Mets a better team whenever it was his turn to try. And besides, as fans who are unshakeable in our affinity, we need these kinds of stories and these kinds of seasons when the overarching narrative is lacking. Dickey winning his 20th as a tuneup for his projected start in Game Two of the NLDS would be as sweet as that sounds, but given what we know as reality, what could be sweeter than a 72-84 club being redeemed regularly by the presence of a 20-6 savior? Savior of our sanity if not our season.”

—A view from the not-so-cheap seats, as sat in and stood in front of on September 27, 2012

“Mets fans in New York City chanted his name, waved giant R’s and A’s and loved him in a way that people love a child or a monk or a dying man who has shed all his armor and come before them in his truth.”

—Gary Smith, current cover story in Sports Illustrated

“This was a baseball decision. And at some point the lines crossed. We did prefer to sign him at the outset. We felt we could sign him. I still felt confident we could sign him as we got into the winter meetings. But it also became clear that against the backdrop of a very hot market for pitching, his value in a possible trade was also skyrocketing. […] His value in trade to us at some point we felt exceeded our ability to keep him here over a one- or possibly two- or three-year period. We’re not going to replace him with a No. 1 starter in return, but we’re going to have to find someone who can give us some of those wins. We also have to hope the team improves in other areas to offset R.A.’s loss. […] R.A. was a very popular player. I’m sure he would have been very popular next year here. I’m sure he’ll be popular in Toronto, and for good reason. On the other hand, our popularity as a team, our popularity among fans, our attendance is going to be a function of winning and losing. And winning and losing consistently over time. Those are the kinds of things we have to take into account. […] I’m hopeful in coming years that our overall popularity will be more a function of our success than individuals. But, look, I recognize this is an entertainment business. It was great to have R.A. here, and yet we felt in the best interest of the organization and the long-term popularity of the team that this was the right thing to do.”

—Sandy Alderson, December 17, 2012

“Sometimes it makes me sad, though, Andy being gone. I have to remind myself that some birds aren’t meant to be caged. Their feathers are just too bright. And when they fly away, the part of you that knows it was a sin to lock them up does rejoice. But still, the place you live in is that much more drab and empty that they’re gone. I guess I just miss my friend.”

—Red, after Andy Dufresne escaped to a better place, The Shawshank Redemption

|

|

Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom.

Plus the bad Mets of the early ’90s have a lot less mythology about them than their counterparts from the early ’60s. Tales of Marv Throneberry and Elio Chacon and Roger Craig are still a cottage industry half a century later, but there wasn’t much to say about Darrin Jackson and Tito Navarro and Mickey Weston then and there isn’t much about them to recall about them now, or at least not much that might cement a boy’s straying fandom.