The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 15 February 2013 11:23 am Congratulations to Elliot, Bill and Joe, three Mets fans whose love for their team dovetailed well with our Valentine’s Day contest. For answering yesterday’s quiz, each wins a copy of The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), the first volume of the four-volume series that tells the story of the New York Mets’ first 50 years through 500 Amazin’ wins. You can get your copy here.

Other developments before we get to the quiz answers:

• Kindle version is closing in on reality. Will let you know the moment it drops.

• The second volume — Second Base: 1974-1986 — is in production and you’ll find out here first when it becomes available. (Spoiler alert: You’re gonna love it.)

• I engaged in what became a pretty passionate interview about the project with the guys from Rising Apple Report the other night: Matt Musico, Rich Sparago and Sam Maxwell. Listen to it here. (I come in around the 9:30 mark.)

• If you’re the mark-your-calendars type, then go to Wednesday, June 26, and circle 7:00 PM. That will be The Happiest Recap Night at Bergino’s Baseball Clubhouse in Manhattan, with book talk followed by proprietor Jay Goldberg’s invitation to stay and watch the Mets play the White Sox (yes, the White Sox) live from Chicago at 8. More details as the date approaches.

As for Bobby and the Valentines…

1. Who was the winning pitcher in Bobby Valentine’s first Opening Day victory as Mets manager?

Turk Wendell, in relief, in the 14th inning of the March 31, 1998 season opener, a game best remembered for Bambi Castillo sending us all home.

2. Three pitchers tied for most games started on the Mets in Bobby Valentine’s first full season as Met manager. Name all three.

In 1997, the ball most often went to the troika of Rick Reed, Dave Mlicki and National League All-Star Bobby Jones.

3. Bobby Valentine wrote John Olerud’s name into the three-hole in 1999 in 159 of 163 regular-season games played. Who were the other three Mets he used as starting No. 3 hitters that year?

Robin Ventura, Matt Franco and Benny Agbayani each filled in orderwise for Oly on his rare days of rest.

4. Who was the last Met to bat in a game managed by Bobby Valentine?

The last batter of the 2002 Met season was Matt Franco, but he was a Brave by then. The answer from the Met side of the box score is Esix Snead.

5. Mike Hampton, Al Leiter, Rick Reed, Glendon Rusch and Bobby J. Jones started 151 of the 162 regular-season games the Mets played in 2000. Who were the other five pitchers to whom Bobby Valentine gave the ball to start the remaining 11 starts in that pennant-winning year?

Now and then you’d get a start from Pat Mahomes, Dennis Springer, Bill Pulsipher, Grant Roberts and the Bobby Jones who was never a National League All-Star.

6. Which six Mets played in the most games during Bobby Valentine’s six full seasons as Met manager?

Going around the horn, there were the five stalwarts of 1999 (and assorted other years): Mike Piazza, John Olerud, Edgardo Alfonzo, Rey Ordoñez and Robin Ventura — and then there was the peripatetic Matt Franco, who nosed out Jay Payton in the call of duty.

7. Bobby Valentine took over Met managerial duties with 31 games remaining in 1996. He used four different starting first basemen during that period. Please name them.

With Rico Brogna already out for the year, Bobby V. leaned on Butch Huskey, Tim Bogar, Roberto Petagine and (there’s that man again) Matt Franco.

8. Bobby Valentine became a Met when he and Paul Siebert were traded from San Diego for Dave Kingman on June 15, 1977. How many hits did Bobby collect in all the games Paul ever won as a Met?

None. Siebert won two games, both of them as Joe Torre’s extra-inning option of something approaching last resort. Valentine batted eight times in those games and went hitless.

9. Between them, how many hits did Bobby Valentine and Ellis Valentine accumulate as Mets?

186; Ellis outhit Bobby 132 to 54.

10. Greg Harts went 1-for-3 in his Mets/major league career. Against whom did he register his only base hit?

H(e)arts and flowers to Rick Reuschel for getting Greg on the board.

Baseball-Reference was the indispensable source for these answers and much that appears in The Happiest Recap.

by Greg Prince on 14 February 2013 2:08 pm POST-VALENTINE’S DAY NOTE: We have our winners. Thanks for playing.

Happy Valentine’s Day! Romantic holiday and all, but flowers, chocolates, Vermont Teddy Bears, hoodie-footie pajamas and $63 Opening Day tickets in Promenade are all passé. The real sweethearts out there give copies of The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973) no matter the date or occasion.

Why? Let me let a satisfied reader who was kind enough to drop me a line testify:

Read your latest book. Then I re-read and reviewed. What a joy! I wasn’t sure about the concept at first. I know so much Met history but did I need to read about a win they were able to put together in mid-1966? The answer is (sorry Marv) YES!!!!! There is so much I didn’t know in your pages and I loved finding it out. What a treat!!! Thank you so much for your contribution to my Met library and I’m looking forward to your future volumes.

Don’t you want to feel that good after a Mets game? If you’re a Mets fan, then after the first 127 of the 500 wins that constitute The Happiest Recap series, you will. Trust me on this. You should definitely purchase one for the Mets fan in your life, even if it’s you. Especially if it’s you.

You’re a Mets fan. You deserve good things.

Read the book. Feel the love. Given that today is supposed to be about love, I would love to make sure at least three of you have The Happiest Recap’s first volume ASAP. So for Valentine’s Day, here comes an unusually un-heartbreaking quiz designed to help three readers who know their way around the source for all answers win a copy apiece. And since it’s February 14, let’s make the subject matter pretty obvious.

1. Who was the winning pitcher in Bobby Valentine’s first Opening Day victory as Mets manager?

2. Three pitchers tied for most games started on the Mets in Bobby Valentine’s first full season as Mets manager. Name all three.

3. Bobby Valentine wrote John Olerud’s name into the three-hole in 1999 in 159 of 163 regular-season games played. Who were the other three Mets he used as starting No. 3 hitters that year?

4. Who was the last Met to bat in a game managed by Bobby Valentine?

5. Mike Hampton, Al Leiter, Rick Reed, Glendon Rusch and Bobby J. Jones started 151 of the 162 regular-season games the Mets played in 2000. Who were the other five pitchers to whom Bobby Valentine gave the ball to start the remaining 11 starts in that pennant-winning year?

6. Which six Mets played in the most games during Bobby Valentine’s six full seasons as Met manager?

7. Bobby Valentine took over Met managerial duties with 31 games remaining in 1996. He used four different starting first basemen during that period. Please name them.

8. Bobby Valentine became a Met when he and Paul Siebert were traded from San Diego for Dave Kingman on June 15, 1977. How many hits did Bobby collect in all the games Paul ever won as a Met?

9. Between them, how many hits did Bobby Valentine and Ellis Valentine accumulate as Mets?

10. Greg Harts went 1-for-3 in his Mets/major league career. Against whom did he register his only base hit?

Got the answers? Send them to faithandfear@gmail.com and, if you’re among the first three with all ten correct, you’ll get the book. Good luck!

Not a quiz taker? Order your copy here. No kidding: if you like the way I write about the Mets, you will enjoy this book a whole lot.

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2013 12:18 am The following passage is from Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live by Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad regarding the show’s first foray into prime time, a 1977 trip to New Orleans for Mardi Gras:

Buck Henry and Jane Curtin were sitting atop their reviewing platform in the middle of the French Quarter, waiting for the Bacchus parade. The exact routing and timing of the parade had been the subject of many hours of discussion between Lorne Michaels and the police department during the week, and they had continually assured him that it would arrive at Buck and Jane’s location no later than forty-five minutes into the show. But by mid-show there was still no parade, and no indication its arrival was imminent. Every ten minutes or so, usually when something else went wrong, Lorne would cut back to Buck and Jane. Having no parade to cover, they filled time with jokes written by Herb Sargent and Alan Zweibel, who were standing just off-camera, scribbling one-liners. In the control booth, people were trying to contact the police, screaming what would become the most repeated question of the night: “Where’s the fucking parade?”

The parade never did arrive, at least while the show was on the air. There were numerous explanations offered later, among them that there had been a fatal accident along the parade route. Finally, in the closing seconds of the show, Jane Curtin turned to Buck Henry and said, “Shall we tell them, Buck? The parade has not been delayed: The parade never existed!”

“That’s right, Jane,” Buck said. “Mardi Gras is just a French word meaning ‘no parade’!”

And Michael Bourn is just a Mets word meaning “no outfield”. No matter how often we uttered it, its definition hasn’t changed.

Michael Bourn, you see, never existed, at least in our world. He was just a rumor. There was one outrageous urban myth making the rounds that intimated he could very well be the Mets center fielder, but only if something happened a few weeks from now with an arbitrator and an agent and a favorable ruling and an inside-straight negotiation. But by then, as anyone with a calendar could tell you, Spring Training will have been long underway, so when you look back on it with just a touch of hindsight, it’s tough to imagine that Bourn — if he indeed existed — was ever going to become a Met.

I sure found myself believing it might happen, though. Made me happy to think it might. I could make lineups with Bourn at the top of them and envision an outfield with Bourn in the middle of it. But I hear players can be had in an amateur draft, and if the famous one-liner scribbler Sandy Alderson is really wise and really lucky, having a pick between the 10th and the 12th in that draft can eventually lead to great things.

Maybe even a parade!

But probably not.

Thing that is real: Me, talking The Happiest Recap and the unhappy outfield situation, on the Rising Apple Report, Wednesday night around 6:40. You can listen here.

by Greg Prince on 11 February 2013 5:47 pm Gentle Reader: The topical hook of this column is incredibly outdated, but the historical stuff is still keen!

***

Michael Bourn. Not a Met. Not yet. Maybe never. Maybe soon. It’s not a story that seems to include resolution. (EDITOR’S NOTE: Resolution came.) But if Bourn is gonna be one of ours soon, he’s gonna start his Met life inside a mixed bag, historically speaking. That’s because if we can get Bourn in a Mets uniform between now and the end of this month, he’ll be a relative rarity: a February Find…a Met who is signed, sealed and delivered in February and plays for the Mets during the succeeding regular season.

Baseball’s clock is already wound in February and the ticking resonates northward. Players can hear it. Agents can hear it. General managers can hear it. It gets late early at camp. Pitchers, catchers and everybody else should be mostly squared away by February. They have to learn the signals. They have to meet their teammates. They have to pose for publicity shots, lest the Official Yearbook be forced to do some ugly airbrushing. Uncertainty is traditionally for November, December and January. February’s for inspection of what was gathered during winter’s hunt. March is for coalescing. April is for delusion, delight, despair, whatever.

Yet sometimes February is for signing on a dotted line. Not that often, but sometimes. There haven’t been many Mets who’ve come on board the month Spring Training commences and been on the team that same year, and not a lot of them left behind distinguished Met tenures (though I’m sure they’re all upstanding citizens with wonderful families). Intuitively, you wouldn’t expect great players to suddenly appear in Mets camp just when the hits are getting real. If a player is available to become a Met anywhere from on the eve of Pitchers & Catchers to the cusp of exhibition games, it can be inferred his pre-Met situation wasn’t ideal. Nobody wanted the guy all winter. Or somebody wanted to be rid of him before he had to be fed and clothed on a per diem basis. Or, as seems to be the case for Bourn (and Kyle Lohse), the entire industry appears flummoxed by new compensation rules where top-notch free agents are concerned. If a fella’s still out there in an acquisition position as February dawns, the reflexive reaction is to ask how good could he be?

Sometimes very good. Most of the time not that great. And what does it say about the Mets through the years if they’re still shopping around as the grounds start getting tended in earnest in St. Lucie or, before that, St. Petersburg?

You might think the Original Mets would’ve had such a revolving door in Camp No. 1 that the Mets would’ve been picking people up off the street, fitting them for uniforms and sending them north after making their February acquaintance. Their legend, after all, includes would-be pitcher John Pappas, the man who paid his own freight down from New York in February of 1962, swore he’d been throwing under the 59th Street Bridge to get in shape and begged Johnny Murphy for a tryout. The press took up Pappas’s cause, so head scout Murphy relented. He watched the kid for less than 20 minutes. His assessment: “I don’t think he could play pro ball in any league.”

Perhaps it’s enough to know a rank amateur could be taken fleetingly seriously to gauge what kind of shape the Mets were in during their first February. Yet the Mets were actually pretty well-stocked numerically if not artistically from the previous October’s expansion draft and weren’t casting about for February refugees. Thus, the only 1962 Met who arrived to stay in February was 35-year-old free agent Clem Labine, more lovingly recalled as an old Brooklyn Dodger, owner of a win apiece from the 1955 and 1956 World Series. Alas, three April 1962 outings pitched to the tune of an 11.25 ERA dictated a change of seasons for this Boy of Summer, who was release and, like Pappas, faced a future devoid of pro ball.

In the early 1960s, there was a first baseman whose defense was notoriously dangerous to his and his teammates’ well-being, yet he had somehow avoided being a Met for the first four seasons there were Mets. Dick Stuart — known as Dr. Strangeglove — somehow seemed destined to fill the spikes once worn by Marv Throneberry and other, less celebrated ball-wranglers around the lukewarm corner. In February of 1966, the Mets sent three players to the Phillies to get Stuart, who was immediately labeled by his suddenly erstwhile employers as “superfluous”.

The Mets didn’t make the deal to add another mitt. Dick once hit 66 home runs in a minor league campaign and had belted as many as 42 for the Red Sox. So what did Stuart give the Mets? Four home runs. And six errors. He was gone by the middle of June, validating the Phillies’ scouting report as they filed the paperwork for his release.

Not every February Met who stuck in the ’60s was on the fast track to retirement. One would eventually contribute to a championship. Ron Taylor didn’t hold much appeal to the Astros, who let him go after two years in Houston and sold him, in February of 1967, to the Mets. Taylor had won a World Series ring as a Cardinal in 1964. Only the dreamiest of dreamers would have projected he’d add a second…as a Met, of all things. It was tough to see in 1967 as the Mets lost 101 games, but Taylor brought the bullpen a touch of professionalism, leading all comers with eight saves and posting impressive WHIP and ERA+ numbers that would’ve been eye-popping had they been calculated during his career.

Two years later, as the Mets won 100 games, Taylor saved 13 of them and established himself as a pioneer of sorts. Not only was Ron the fireman on a world championship club, he was making 59 of what would become 269 relief appearances between 1967 and 1971 — yet he never started a game as a Met, which was a revolution unto itself. Ron Taylor was the first pitcher in Mets history to work exclusively out of the pen for a significant, extended period.

Up until Taylor, no Met kept relieving simply because he was good at it. In the franchise’s first decade, no Met pitcher came within 200 relief appearances of Taylor without making a start. (Runner-up: Don Shaw’s 47 appearances in 1967 and ’68.) Even as baseball entered an age of specialization, Taylor’s place in Mets history held. His franchise record for most games by a 100% reliever stood until John Franco topped it in the mid-’90s. Only Franco, Pedro Feliciano, Armando Benitez and Turk Wendell have put in more relief appearances as a Met without ever starting than Taylor.

But Taylor’s the only one in that group to win a World Series as a Met. No other February-signed, sealed and delivered Met has won one, either.

If you want a more glamorous record, one that requires minimal explanation, you can’t beat what the Mets came up with at the end of February 1975: Dave Kingman. The cash-strapped Giants sold him, the Mets bought him and he shattered Frank Thomas’s single-season home run mark of 34 right away, slugging 36 in ’75, then 37 in ’76. The Mets traded him anyway in 1977 when they were on a star-deletion kick.

Because acquiring Kingman in February worked so well, the Mets did it again six years later. On the very same date in 1981 — February 28 — the Mets went out and bagged themselves Sky King once more. This time it took Steve Henderson plus cash to the Cubs (who, like the Mets of ’77, did not share Dave’s interest in renegotiating his contract) to get it done. Once again, Kingman clouted voluminously. Once again, Kingman was elsewhere three Februarys later.

In between crowning a pair of Februarys with Kingman, the Mets snuck in Luis Alvarado in February 1977. He played four innings in one game that April. Soon he was a Tiger. Soon after that, he was done. Clem Labine could have warned him about how that goes.

When the Mets made their next non-Kingman February deal, it appeared they were just getting started on something big. In February of 1982, they shipped useful if power-deprived catcher Alex Treviño, ambidextrous pitcher Greg Harris and paper Met Jim Kern (obtained in December for Doug Flynn) to Cincinnati for one of the best players baseball had seen over the previous half-decade, George Foster.

That was the kind of February trade that didn’t happen every year. But the Reds were facing Foster’s walk year, the Mets were in dire need of a splash and a swap was born. The Mets didn’t blink at the five-year commitment and many millions of dollars it would take. They were thrilled to have a slugger of Foster’s ilk to pair with a slugger of Kingman’s ilk. True, the ilk went sour pretty quickly (Foster’s 1982: 13 HR, 70 RBI, .247 BA), but it stands as the most stunning move the Mets ever made in a given February…no offense to the February 1987 return of bad-timing king Clint Hurdle (a Met in ’85 but not ’86) or the February 1989 signing of Don Aase, the reliever who ousted Tommie Agee from the top of the franchise’s alphabetical chart.

Mets personnel was relatively stable most Februarys in the 1990s, a touch ironic given the franchise’s general state of flux in those days, but their one February acquisition during the decade proved as important as any in building a playoff team. In February 1998, the Mets took off the hands of the Florida Marlins Al Leiter, a vital component of the Fish’s 1997 world championship, which made him, of course, priced to move during Marlin owner Wayne Huizenga’s instantly executed fire sale. Leiter cost the Mets three minor leaguers, only one of whom — A.J. Burnett — truly blossomed. Leiter won 95 games in seven Met seasons, helmed a series of aceless pitching staffs and grimaced a thousand soulful grimaces during the gut-wrenching playoff-laden autumns of 1999 and 2000.

Come the turn of the century, February went wild, with the Mets bringing in a series of fringe players who made the team nonetheless. Leiter’s pennant-winners of 2000, for example, were fortified by four February signings: Dennis Springer, David Lamb, Mark Johnson and the irredeemable Rich Rodriguez. None of them was on the roster by October, but they all contributed to (or, in Rodriguez’s case, detracted from) the greater cause.

The Art Howe years were ripe for February flotsam to float ashore the Gold Coast beaches of Florida, indicating perhaps that much was up for grabs in the glow of the manager lighting up St. Lucie’s various rooms. Those who made the team at some point in 2003 were a Recidivist Met (David Cone), a veteran finishing up (Jay Bell), a middle reliever just establishing his value (Dan Wheeler) and a galling case of nepotism (Mike Glavine). One February later, there’d be no nepotism, but a touch of recidivism (Todd Zeile) and out-and-out decrepitude (Scott Erickson, Ricky Bottalico and James Baldwin). With that assortment of talent flickering on and off through the Howe epoch, it’s no wonder the lights went out on it after two seasons.

From 2006, when times were good, through 2011, when things were markedly less so, a stream of placeholders jumped aboard the Mets express as it alternately chugged and crawled on its appointed rounds. Late-winter/early-spring uncertainty yielded the likes of Jose Lima in ’06; Chan Ho Park in ’07; Chris Aguila, Ricardo Rincon and the second coming of Brady Clark in ’08; Elmer Dessens in ’09; Luis Hernandez, Jason Pridie and Mike Jacobs II in ’10; and Dale Thayer in ’11.

But there were some finds amid the debris in the era that saw the Mets slide from contenders to dead-enders.

• Pedro Feliciano returned from Japan in February 2006 and stayed like crazy through 2010 before harmlessly detouring through some other uniform for a couple of inactive yet nicely remunerated years. Like a faithful LOOGY, he has come romping home once more.

• Nelson Figueroa wrote a touching story as a Brooklyn boy doing his best in Queens by pitching his way back to his first organization, never mind his childhood team, in February 2008. It didn’t end well (does it ever with the Mets?), but it was a February investment that paid off in the short-term.

• Liván Hernandez, who always seemed like someone the Mets were on the verge of acquiring, did, in fact, sign with the Mets in February of 2009. He’d be gone by August, but not before throwing the first (albeit exhibition) Met pitch in Citi Field history.

• Hisanori Takahashi alighted in camp in February 2010 and gave the Mets as much bang for their buck as any starter/reliever had since maybe Terry Leach: a dozen starts, eight saves, ten wins overall.

• Rod Barajas was a last-minute, last-resort signing in February of 2010 (as the starting catcher responsible for handling a dozen different arms), and if only the season had ended in June, he might have vied for National League MVP. He was a Dodger by August.

• Jason Isringhausen proved like so many prodigal Mets before him that it paid to have a track record somewhere when reporting date was bearing down. Izzy was welcomed back to the Mets bullpen in February 2011 and hung in there long enough to record his 300th save six months later.

Oh, and one more February transaction during this period that bears noting: four youngsters dispatched to Minnesota for Johan Santana in early February of 2008. The mega-megabucks deal that brought him to New York at least matched Foster’s for generating immediate enthusiasm and the output — 46 wins as a Met, two of them (the last at Shea; the first with no hits) transcendent — made it as good a deal as any finalized in February. Taylor was a part of something bigger, Leiter did more heavy lifting and Kingman may have been more mythic at his specialty, but Johan Santana three-hit the Marlins when it mattered most and no-hit the Cardinals, which will matter forever. Johan Santana is the emperor of February arrivals.

It’s hard to imagine any Met to launch in February could match those singular accomplishments (Johan’s expensive injury-wracked voids notwithstanding) he could Santana be surpassed by this month’s signature finds? By a Marlon Byrd…or a Brandon Lyon…or a Michael Bourn maybe?

It’s hard to tell right now. After all, it’s only February.

UPDATE: Bourn signs with Cleveland. But we’ll always have Luis Alvarado.

by Greg Prince on 9 February 2013 9:02 pm Pitchers are the early objects of attention and, potentially, affection at Spring Training. Catchers tag along dutifully. Yet it would be athletically incorrect to frame them that way, so we politely refer to this golden interval in the dead of winter as Pitchers & Catchers. Most years, it could be Pitchers & Pitchbacks for all we reflexively care about the receiving end of this equation. It’s not like we’ve been given much reason to dwell on or drool at Mets catchers these past five years.

The second week of February 2013 (spring, my ass; look out the window), however, seems a little more promising where the “2” on your scorecard goes. Our — or anybody’s — greatest-hitting catcher ever is poking his head out of self-imposed exile to promote his new autobiography. Our best excuse for not torching Citi Field in the wake of the exportation of R.A. Dickey is finally getting his picture taken in something other than a Blue Jays cap. And our temporary starting catcher is showing he’s something of a live wire, at least provisionally.

Mike Piazza didn’t do steroids, he says. Travis d’Arnaud hasn’t done anything, but we assume he will. John Buck? I kind of liked the cut of his jib when I saw him on Hot Stove the other night. Mets catchers’ jibs have almost uniformly lacked zazz since the De Parture of Lo Duca. They’ve all been underformed or overcooked. Some of them seemed genial enough yet demonstrated quickly they were, as Mets, skill-averse. Buck? He’s spent two years accumulating more strikeouts (218) than batting average points (.213 overall), but he’s already won me over, February-wise, by going on with Kevin Burkhardt and seeming a) more than competent and b) excited to be here. Ed Leyro considers the early evidence at Studious Metsimus and makes the case that John could be something of a catcher-coach. I don’t know if that makes him a latter-day Yogi Berra, but anyone who isn’t, say, Brian Schneider I’m willing to call an improvement.

Brian Schneider just retired, by the way. Maybe if I’d been in a better Met mood when Schneider first reported to St. Lucie as the well-respected veteran catcher de l’anée around this time in 2008, I would’ve found some reason to see him as a sage. But I was in a lousy Met mood post-2007 and Schneider’s wan presence didn’t help it. His brand equity wasn’t substantially different from Buck’s, except he never gave a cheery interview that I can recall. As Jules noted in Pulp Fiction as he debated pigs versus dogs with Vincent, personality goes a long way. (That might also explain Jeff Francouer’s extended big league engagement.)

I never much cared for Schneider, but I have no reason to doubt his bona fides as a human being. He could’ve said, “I’m done” and gone on a cruise. Instead, he joined a mission of current and former players to bring a little Spring Training to American troops stationed in Germany this month. “I want them to have the opportunity to see guys they grew up watching or who they see on TV now,” he said. “I want to have the opportunity to thank the troops because what they do on a daily basis is more than we know.”

It’s not the first time Schneider has been attached to a good cause. Upon his arrival on the Mets, we learned there existed (for a while) Brian Schneider’s Catching For Kids Foundation because there was a wine created to raise funds for it: Schneider Schardonnay. It came out in 2008 in conjunction with Santana’s Select, CaberReyes and some other player-named varietals. Most of the players were stars. One was Brian Schneider.

Fired up? Ready for him to go was more like it. I can’t say I was fired up to own a bottle of Schneider Schardonnay, no matter whom it benefited. I can’t say I was fired up about Brian Schneider ever, no matter what he did. Not that he did much as a Met. Some players just let you down even if you expect nothing out of them. That was Brian to me. In two Met seasons, he batted .244, he OPS’d .680, he compiled a WAR of 0.3, he rarely lived up to his defensive billing and whatever he did behind the scenes in his final month here, his mentoring of Josh Thole didn’t pay many dividends.

Then Schneider went away, became a Phillie, mentioned the little differences between the two organizations (for example, in Philadelphia, they would win and only then would they enjoy a Royale with Cheese), batted a Buck-like .213 for three seasons and retired. I didn’t miss him.

But I did wind up with a bottle of his wine. My brother-in-law came across one in a Trader Joe’s a year or so ago and picked it up for me. He didn’t know Brian Schneider from Brian Boitano, but he saw orange, blue and a chest protector and figured it was right up my alley…which it was, more or less, if you eliminate my distaste for the player pictured in the chest protector. Still, it was a thoughtful gesture, even if Schneider Schardonnay was immediately stuck in our lightly visited cabernet cabinet and completely forgotten about.

On Thursday, with the latest storm of the century bearing down on us, Stephanie asked me to pick up some ingredients for a slow-cooker dish she decided to try in anticipation of being snowed in. The recipe called for one cup of “dry white wine”. I didn’t buy any because I assumed one of our cooking-specific wines would cover it. She said it didn’t, that we still needed some. Hey, I know, I said, reaching deep behind some paper towels and cat treats, why don’t we use this?

Brian Schneider may not have been the missing ingredient in a Mets championship, but he sure as hell fit the “dry white” description. And he worked out fine in a dish of creamy chicken and mushrooms even if he never clicked behind the plate at Shea Stadium or Citi Field.

Maybe it takes a dull catcher to make a tender chicken.

FYI, I’m scheduled to be on the air in Brian Schneider Country this Monday afternoon at 3:15, on WBCB (1490 AM), to talk Richie Ashburn, Original Mets and The Happiest Recap with Skip Clayton and Cassie Gibson. If you’re not in the Lehigh Valley, you can listen here.

by Jason Fry on 6 February 2013 4:59 pm In a few short days, pitchers and catchers, David Wright and any players wise enough to understand Terry Collins’ odd definition of “on time” will all have assembled in Port St. Lucie for spring training. Which will be nice — but not because it’s a sign of spring.

That doesn’t really work for me any more. Spring training is way too long for everybody except pitchers, and for my initial joy now lasts about 10 minutes, to be replaced by grumbling that we’re looking at six weeks of boredom, frustration and eight to 10 variants of the same story of the day, while sifting through small-sample-size tea leaves (“Ike Davis is hitting .483!”) and phrenology (“Coaches are praising Jordany Valdespin’s new attitude!”) to make predictions that will prove absolutely useless when the real games start.

No, the pop of balls in mitts will be nice because it will mean one of the weirdest, most frustrating offseasons in Mets history is finally nearing an end.

There’s really only one question that matters in assessing the Mets these days: When will the National League’s New York franchise once again be funded in the way the National League’s New York franchise should be funded?

To that, if you want, you can append a related question: If no one knows, or the answer isn’t “soon,” what needs to change and how does that happen? But that’s a follow-up question, one that depends entirely on the answer to the first one.

Seriously — nothing else particularly matters. Can Lucas Duda play a semi-capable left field? Will this year’s bullpen be better than last year’s? Can Daniel Murphy, Jon Niese, Dillon Gee and Ruben Tejada take steps forward? When will Zack Wheeler be ready? All interesting, to be sure, but they’re just curiosities compared to the real question.

Even without the Wilpons’ financial woes, it’s wise for Sandy Alderson to get out from under big contracts such as the ones paid to Jason Bay and Johan Santana. It’s wise for Alderson to eschew Omar Minaya’s hideous habit of giving out expensive, easily obtained option years. It’s wise to see the farm system rebuilt and the team reconstructed on a sensible, unsentimental foundation of developing cheap talent and controlling that talent’s prime years.

But without the ability to build something on that foundation, none of this matters — the Mets, at best, will be trying to catch lightning in a bottle. And at worst, we’ll continue to see what we’ve seen in recent years: financial uncertainty that’s so pervasive that a fan has no idea of what’s possible and no sane expectations except to shrug. Ultimately, I think that’s more damaging to a fan base than fallow years of rebuilding. Rebuilding ends. What the Mets are doing right now might end, or it might not — because nobody can tell exactly what is that the Mets are doing.

Personally, I don’t believe Sandy that the decisions to spend or not spend are his — I think he’s being a good soldier for owners who remain in a perilous position, and whose orders are constantly changing. But I’m no longer interested in debating the question. It’s pointless and I just want it to go away, because questions like that and posts like this are no fun. But that leaves us stuck where we before — debating, say, the future of Matt Harvey when the real question is if Matt Harvey will have to be traded away before a postseason club can gel around him.

Which makes the farcical Michael Bourn saga perfect for this weirder-than-weird offseason. The Mets indicate they’re interested in Bourn, an honest-to-goodness big-name free agent. Provided they can get MLB to rule that they don’t have to surrender their 11th pick. But MLB won’t decide on that unless there’s a deal in place. And the Mets won’t make a deal unless they don’t have to surrender their 11th pick. And even then Scott Boras might just be creating a stalking horse for someone else. And even then this is a Mets team that seemed to think Scott Hairston was too expensive. And round and round we go, until the pointlessness is downright dizzying.

I’m not sure I can get past this corrosive uncertainty and manage to give a fig about Daniel Murphy looking better turning the pivot or LaTroy Hawkins offering veteran leadership. But after a winter like this, it will be a relief to try.

by Greg Prince on 5 February 2013 6:00 pm “When you’re dating,” Shrevie (Daniel Stern) advised Eddie (Steve Gutenberg) in 1982’s Diner, “everything is talking about sex. Where can we do it? Why can’t we do it? Are you parents gonna be out so we can do it?” I was having conversations like those in 1982, though my “it” was usually different from the movie’s. The “it” for me in 1982 and many, many other years was the Mets’ contending.

When can we do it?

What will it take for us to do it?

Who might we be doing it with?

How will we know for sure if we’re doing it?

Why can’t we do it NOW?

As a Mets fan during extended blue periods, I’ve maintained a notoriously one-track mind. We may not be very good yet, I’d think when things were rotten, but if this and this and this happen, we stand an excellent chance of being, dare I say it out loud…not bad!

Mind you, that’s all I was going for: not bad. Not bad equaled legitimacy. Legitimacy equaled the cusp of contention. Contention was the access road to happiness. If you could tell me the Mets were good enough to maybe win, then I was good for the next six months. Plausible truths and self-deceptions got me through a lot of blue.

Just not that much lately.

Sandy Alderson’s semi-bold pronouncement Monday that “we’re not that far away” got my attention because at no sustained interval since the Mets stopped contending as a matter of course have I thought we were close enough to start thinking about being not that far away. Furthermore, I didn’t spend much time dreaming of getting closer because I’d become convinced that wasn’t something that interested either Mets management or ownership.

I watched contention slip away after 2008 and I grew surprisingly used to its absence fairly quickly. I didn’t like the concept of entering a season convinced we didn’t have a chance — or digging deep into a season unwilling to acknowledge those specks of shiny substance occasionally detectable in the cloud-linings were, in fact, silver — but unlike 1977-1983, 1991-1996 and 2002-2004, I found myself accepting non-contention as if it was the norm. I don’t know if it was the stream of ready-made financial excuses we’d been fed or the lack of urgency attached to the front office’s public demeanor or the determined non-competitiveness displayed on-field across four second halves played out under the auspices of two very different administrations. But wittingly or otherwise, I’d put the concept of contention almost out of my Met mind since 2009.

Carping for the construction of a better team as soon as possible seemed to border on ungrateful unsophistication. Wasn’t it enough that Alderson and his deputies were clearing out the excesses lingering on the books from the Minaya regime? Didn’t I understand the hit the Wilpons took away from baseball? Sell the team and we can talk; until then, stop expecting satisfaction from the thing you love.

So I stopped. I stopped having expectations. I stopped having dreams. I stopped having aspirations, short- or long-term. Rebuilding — payment of lip service notwithstanding — seemed like a crock, too, once we had to hunker down and actually do it.

Rebuilding with what? The minors? Every team has those. The draft? Every team’s in that. One trade of one expiring megacontract for one überprospect? OK, we’ve got Zack Wheeler. That left us with a system that hasn’t produced anybody outstanding in almost a decade plus one pitcher. Is this how rebuilding works?

Maybe so. Maybe it’s Wheeler plus d’Arnaud and Syndergaard, plus Harvey, who was actually a little something special during an extended glimpse. And could it be that Niese will outstrip my mistrust and dismay over his painfully gradual learning curve? Is that the bulk of a really promising long-term rotation, not to mention a battery, I see in there?

And how about that infield? Wright didn’t leave. He was never going to leave, but now we know for sure. Goodness knows Davis and Murphy and Tejada have their flaws — or at least have yet to prove fully formed — but all told that doesn’t project as a bad infield…does it?

The bullpen? I don’t know. It’s got to be better than it’s been, but I say that every year. Brandon Lyon could be a useful addition, never mind that’s what I was told about Ramon Ramirez and his myriad offseason upgrade predecessors; Ramirez, like Andres Torres, is suddenly a San Francisco Giant again, just like Angel Pagan. Still, Parnell almost seemed to have it together late last year. Edgin was darn effective until he ran out of gas. Carson wasn’t terrible, either. Relievers are always mix-and-match anyway. Maybe we really have a little better bunch to sort through.

The outfield is still the outfield, but if I stare at it long enough…

Didn’t we have high hopes for Duda? If he hits and they just leave him in left, isn’t it possible he could string together more than a few weeks when he’s as scary at the plate as he is in the field? Weren’t we psyched about Nieuwenhuis for about a month? The league figured him out and then he got hurt. He’s healed and, who knows, perhaps he’ll figure out the league. And Bourn…

Bourn’s not here, man. He’s a big-name free agent. The last big-name free agent we signed was Sandy Alderson. But what if Bourn somehow got here? What if Sandy sweet-talked some combination of Scott Boras and Bud Selig? What if the money and length weren’t prohibitive and the draft business would just take care of itself conceptually if not perfectly?

How about a legit center fielder to take some pressure off Lucas? How about getting a leg up on overall improvement with a guy who can actually run and has actually hit? Bourn’s a week younger than Wright and we’re (more or less) thrilled to have David on board for eight years. Is Michael Bourn really gonna evaporate at age 30? At age 32?

Santana’s his usual expensive functional question mark, but only for another year, and besides, who’s to say he won’t be fully refreshed once and for all after a winter of rest? Gee I don’t know about coming back in form, but if he does, I had all the confidence in the world in him. And Marcum: a real pitcher, not a trash heap find! Francisco, Parnell, Lyon, Edgin, the youngsters like Familia and Mejia, maybe an oldster like Feliciano or Hawkins…the lot of them can’t be any worse than whoever and whatever were here last year at this time. Besides, a good rotation tends to lean on the bullpen a lot less, and an unleaned-upon bullpen probably automatically makes for a better bullpen.

John Buck always killed us if nobody else. Maybe Justin Turner is even more versatile than we realized. Mike Baxter is faith personified. Collin Cowgill really hustles, somebody swore.

No, I don’t expect a lot in 2013. But I’m not resigned to it. I’m even finding myself a wee bit feisty about it. I watched an MLB Network show about the best first basemen in the game and was actually moderately insulted when Ike Davis’s name only came up once. Ike was noted as the first baseman who hit more home runs than every first baseman in 2012, save for Edwin Encarnacion and Adam LaRoche. I wasn’t insulted Davis didn’t supplant Votto, Pujols and Fielder in the hosts’ wide-ranging esteem — I was insulted that when Ike’s name came up for his 32 home runs, I could discern the slightest chuckle that they had to bother mentioning a Met.

I wonder when the last time was that I could feel myself angering at the underestimation of a New York Met. For that matter, I wonder when the last time was that I tuned into a show just so I could hear if they were going to mention a Met and therefore get excited about his and our progress. That’s the sort of thing I would have done between 1977 and 1983, 1991 and 1996, 2002 and 2004. That’s when I could dream of the Mets as contenders even if they weren’t quite there yet. Even if they weren’t remotely close to quite there yet.

It feels good to dream of “doing it” again, no matter the dream’s state of readiness as it relates to reality. After four losing seasons, dreaming it can be almost as satisfying as actually doing it.

Listen to a swell conversation that recalls the days when the Mets were doing plenty, as Jason joins Matthew Callan to dissect Game Two of the 2000 NLCS (featuring Rick Ankiel’s meltdown) on Matthew’s excellent podcast series Replacement Players.

by Greg Prince on 3 February 2013 3:30 am Soon enough, we will concern ourselves with Spring Training hellos, including those from the Mets’ most recent flurry of somewhat tentative acquisitions. There’ll be first-pitch greetings from Shawn Marcum, Scott Atchison and LaTroy Hawkins; first-catch greetings from Landon Powell; greetings for the first time in a little while from previously dispatched Omar Quintanilla; greetings for the first time in a couple of years from Pedro Feliciano (if he has a spare moment when he’s not warming up in anticipation of facing Bryce Harper 19 times this season); and at least one fellow with the initials M.B. waving “HI!” from the outfield — Marlon Byrd definitely, Michael Bourn maybe. The Mets might lack for glamorous, in-their-prime signings, but they won’t be shy of guys introducing themselves to us.

We’ll want all our newcomers to show us something in St. Lucie. Those who do we’ll want to see in Flushing. From there, we’ll want them on the field for seven months, including a generous portion of October.

And if they have to say goodbye after playing a role in turning our milieu into the Promised Land, we’ll understand.

Actually, we’ll qualify that should it become an issue, for we might want to keep our hypothetical world championship team together so it can form a dynasty. But, really, if someone wants to win us a World Series and be on his way to the next phase of his life, it would be rude to throw up any substantial roadblocks.

When the Super Bowl gets underway Sunday night after the completion of its 140-hour pregame show, one of the major storylines will center on Ray Lewis and his attempt to end his career by earning a Super Bowl ring. You may have heard, among other things, that the Ravens’ linebacker will retire when the game is over. If he rides into the sunset in a swirl of confetti (and isn’t caught doing anything illegal en route), he will go out in the best competitive light possible…in the reflected glow of the Vince Lombardi Trophy.

Lewis attempts to do what a handful of all-time greats have done. This was the way for John Elway, Michael Strahan and a few other football notables who won a Super Bowl and then immediately said goodbye. It’s also how David Robinson and Mitch Richmond went out in basketball, a fact I remember only because they won their last games in NBA Finals clinchers against my occasionally beloved Nets (whereas the Nets ended the ABA’s collective career as league champions, though that’s not precisely the same thing).

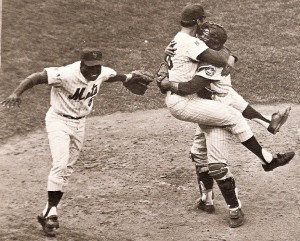

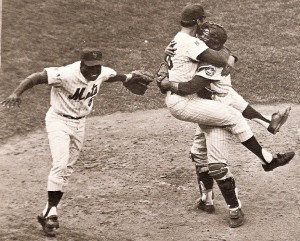

And then there was the sole New York Met whose final game as a professional baseball player wound up with him in the middle of a world championship celebration. That Met was the third man to arrive at the Shea mound as the cameras clicked after the last out was recorded…and he was the first within their ranks to leave the playing field altogether.

Gliding into euphoria and soon off the stage. Ed Charles certainly waited long enough to become a World Champion. He endured a decade of minor league ball, not because he wasn’t good enough to make it in the majors, but because he chose the wrong time to be young, African-American and in a sport that clung to shameful unofficial quotas regarding how many like him could be on a roster at a given juncture. That’s just surface stuff, of course, for there was nobody “like” Ed Charles: poet laureate of a youthful band of miracle workers and veteran leader among mostly callow kids. Ed was as much the toast of New York on October 16, 1969 as picturemates Jerry Koosman and Jerry Grote, not to mention Tom Seaver, Cleon Jones and everybody else in a Mets uniform. The Glider rushed the Jerrys and embraced the team’s fate as hard and lovingly as anyone could have.

Charles’s final appearance as a big leaguer came under the best possible circumstance. His exit, however, wasn’t planned in the fashion of Lewis’s at this Super Bowl. There was no goodbye tour for the platoon third baseman, no string of press conferences. There was just a perfunctory release a dozen days after he hugged Grote and Koosman. There were some hard feelings between unceremoniously deleted player and bottom-lining front office at the time, yet Charles has been as constant a presence among Mets alumni as any of his brethren in recent decades. He went out on top and he’s remained steadfast among us, proving the best farewells are sometimes the ones that are mere partial finals.

One short rung down on the goodbye ladder, at least in terms of the achievement/aftermath dynamic, are a pair of Mets who played on October 27, 1986, and went out the biggest of winners. Ray Knight hit the difference-making home run that Monday night at Shea and captured the World Series MVP award. Less instrumental in Game Seven was starting left fielder Kevin Mitchell…though he — like Knight, Gary Carter and Mookie Wilson — basically ensured there’d be a Game Seven by executing flawlessly in the tenth inning of Game Six.

Knight and Mitchell finished their Met careers by winning a World Series but then continued to play on elsewhere, allowing them to linger palpably as avatars of what might have been in the Metsopotamian imagination. Neither’s departure was voluntary let alone overly popular. Ray wasn’t offered the money he wanted and signed a lesser deal with Baltimore; World (as in all-world for the plethora of positions he manned) was sent away to San Diego, lest he unduly influence a couple of impressionable young New York Mets. Howard Johnson effectively succeeded Ray Knight at third. Kevin McReynolds, for a while, was an upgrade over Kevin Mitchell. Sentimentally, one can make the argument that each tilted fairly close to irreplaceable.

Only one other Met played his last game as a Met as the Mets were nailing down a postseason series. Remember Chris Woodward? Handy utility type from the middle of the last decade? Woodward saw limited action in the 2006 National League Division Series. His only appearance came when Willie Randolph led him off in the top of the eighth of Game Three as a pinch-hitter for Guillermo Mota, the Mets up on the Dodgers, 7-5. Chris doubled against Brett Tomko, advanced to third on a Jose Reyes flyout and scored when Paul Lo Duca singled. Two innings later, the Mets were NLDS winners in a three-game sweep.

The action was even more limited for Woodward in the NLCS: seven games, nothing doing. Thus, Chris’s last Met appearance came on October 7, 2006, in the cause of a series win…a division series, but still a decent way to make a final impression. The Mets replaced Woodward with David Newhan in 2007 and, probably coincidentally, haven’t been in the postseason since. Woodward bounced about the majors in a utility role until 2011, never again seeing the business end of October. Yet Chris, at 1-for-1, possesses one of only two 1.000 career Met postseason batting averages. The other belongs to Jesse Orosco, who swung away in the eighth inning of Game Seven of the 1986 World Series to drive in the Mets’ eighth run. Orosco would pitch another seventeen seasons but never again record an RBI.

Four other Mets unknowingly said goodbye to us, if not baseball, in postseason wins:

• J.C. Martin’s final contribution to our well-being came at the expense of his wrist, struck by Pete Richert’s toss after J.C.’s bunt in the tenth inning of Game Four of the 1969 World Series. The ball hit Martin as Martin hustled down the line (literally). It bounded away, permitting Rod Gaspar to score the winning run from second. J.C. didn’t play in the fifth game and was traded to the enemy Cubs the following spring.

• Danny Heep pinch-hit for Rafael Santana in the fifth inning of Game Six of the 1986 World Series (before that contest became historic and was merely agonizing). Heep’s double play grounder brought home Knight with the tying run, no small feat given the Mets’ desperation to generate offense versus Roger Clemens in the truly must-win affair. Clemens had been no-hitting the Mets for the first four innings of the sixth game. A productive out was, if not as good as a hit when Heep made it, then critical. That swing completed Heep’s active Met tenure. By 1987, he was a Dodger. By 1988, he was a world champion again.

• Masato Yoshii threw the first three Met innings on October 17, 1999. Octavio Dotel threw the last three that same Sunday. In between, the Mets and Braves played 14½ innings, leaving the Mets down a run, yet saving the best for last in the bottom of the fifteenth: a dozen pitches to Shawon Dunston before he singled; a stolen base; a walk, a sacrifice, a couple more walks; and something with a home run that wasn’t really a home run (even if it kind of really was). While Mets fans soaked in Robin Ventura’s Grand Slam Single in Game Five of the NLCS, keeping the Mets improbably alive for the pennant, they couldn’t have realized they had witnessed the final Met appearances of Yoshii and Dotel, neither of whom were tabbed to pitch in equally epic Game Six (just about everybody else was). Masato was traded to Colorado for Bobby M. Jones three months later and would eventually return to Japan, pitching there through 2007, when he was 42. Octavio went to Houston as partial payment for Mike Hampton in December of 1999 and was, at last check, ageless.

Twenty-one other Mets made their final Met appearances in postseason losses. No sense reliving those incidents, but their ranks include Willie Mays and Jim Beauchamp (1973 World Series); Wally Backman (1988 NLCS); John Olerud, Bobby Bonilla, Orel Hershiser, Dunston and Kenny Rogers (1999 NLCS); Derek Bell (2000 NLDS); Hampton, Bobby J. Jones, Mike Bordick, Matt Franco, Kurt Abbott and Bubba Trammel (2000 World Series); and Steve Trachsel, Darren Oliver, Roberto Hernandez, Chad Bradford, Michael Tucker and Cliff Floyd (2006 NLCS).

Is there a long-term lesson inherent in all this for our array of Spring Training invitees as they attempt to play their way into our good graces? Perhaps it’s if you can’t say goodbye as a champion, then at least stay as late into the fall as you can.

Immerse yourself in thirteen Amazin’ playoff and World Series wins — plus 114 meaningful, memorable, milestone victories from the Mets’ first thirteen regular seasons — in The Happiest Recap: First Base (1962-1973), the perfect way to say goodbye to winter and hello again to baseball.

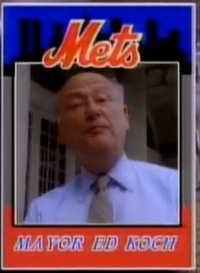

by Greg Prince on 1 February 2013 9:45 pm  Presided over the teamwork that made the dream work. “You have to give it your BEST shot, and then you come out No. 1 — the Mets!”

So said Mayor Edward I. Koch in 1986 at the end of the closing credits to An Amazin’ Era, the club’s 25th Anniversary video.

No, I don’t know what he meant exactly. But it sounds sage, doesn’t it? And after he said it, the Mets went out and won the World Series, didn’t they?

If that’s how they were doin’, then Mayor Koch made as much sense as he possibly could. Hizzoner wasn’t any kind of a sports fan. He was good for about an inning on Opening Day and maybe the seventh game of a Fall Classic when one materialized on his watch.

Yet it’s hard to believe anybody ever rooted New York home any harder.

by Greg Prince on 30 January 2013 1:42 pm Nancy, who is originally from Long Beach, attended college at Stony Brook, where she roomed with Sue, who married Jeff, a D.C.-area standup comic and Mets fan who read a Mets blog enough to want to reach out to one of its co-authors, Greg…who is also originally from Long Beach. Jeff contacted Greg after Greg veered off format one December day and wrote about the music he really likes, which happened to include some of the same music Jeff really likes. Greg and Jeff soon became very good friends, enough so that when Jeff does standup in New York, Greg comes to see him perform even though Greg doesn’t much like comedy clubs.

Monday night, Jeff did standup in New York and Greg showed up. So did Nancy, who is still very good friends with Sue. Jeff introduced them to each other as people who were both originally from the same town. As will happen when those kinds of stars align above our small world, Nancy confirmed Greg’s last name and asked him if he was related to Suzan. Yes, Greg said, that’s my sister.

Nancy knew Suzan. She mentioned quite casually they were on the same high school newspaper. Suzan was its editor-in-chief (something Greg would be several years later). Greg was rather surprised by this revelation. Maybe revelation isn’t the right word, since this was a tidbit from the distant past, but still, what an odd juxtaposition of degrees of separation, he thought. Two ostensible strangers sitting in a comedy club, waiting for their mutual friend to perform, making small talk, and one knew the other’s sister a very long time ago.

As Greg tends to do when the world proves that small, he ran a quick search of his mental card catalogue and pulled up some names he still associates with Suzan’s high school newspaper days, names that came home with his older sister every day. Greg was just in elementary school then and found her stories as interesting as he’d ever find them. The first name Greg thought of was Phil, who wasn’t just a name to Greg. Greg remembered Phil pretty well. Surely if she was part of that scene, Nancy would remember Phil, too.

Oh yeah, Nancy knew Phil back then and was aware of him more recently via Facebook. Phil, Nancy reported — again fairly casually — died just a few weeks ago.

Greg hadn’t seen Phil in close to four decades, but he was thrown by the news. Phil would’ve been just a little younger than his older sister. These days Suzan isn’t that much older than Greg. Time flattens out as you age, leaving all involved sufficiently advanced no matter the precise vintage of one’s graduation date. Yet we’re all too young for the fate that befell Phil.

Phil’s life went on after Suzan finished high school and the two of them drifted apart. In Greg’s mind on Monday night, however, the four intervening decades cleared out and it was a Saturday afternoon at the end of June 1974…a Saturday afternoon at Shea Stadium.

It’s often a Saturday afternoon at Shea Stadium in Greg’s mind, but this Saturday afternoon, June 29, 1974, was the first Saturday afternoon he’d ever actually spent there. It was Greg’s second Mets game overall. His first Old Timers Day, which was why he chose the date when he was asked to pick. His first win. His first one-hitter — Jon Matlack’s, technically, but the first of many near-misses Greg would manage to see live before Johan Santana threw the Mets’ first no-hitter and rendered tracking one-hitters superfluous. Suzan, chronically disinterested in baseball but an All-Star as a big sister, offered to take her little brother to his favorite thing he usually only got to see on television or hear on the radio. He asked for Old Timers Day. She asked Phil to come along.

The three of them took the Long Island Rail Road to Shea. Greg doesn’t know for sure, but assumes Phil knew how to do that. Greg didn’t. Suzan couldn’t have — she’d never been to a Mets game before. Phil struck a New Yorker’s air of sophistication, of knowing about things that seemed worth knowing, of knowing more than most high school kids from Long Beach were likely to know, at least from Greg’s perspective. Phil knew about movies. Phil knew about Broadway. When he wasn’t writing for the high school newspaper — succeeding Suzan as editor-in-chief — Phil worked at the Jack In The Box, where, he advised, you didn’t want to know what they did to the fries when no customers were around and the guys who manned the grill got a little bored. Phil was very quick-witted, very funny, certainly to a little brother’s sense of what was hilarious. Phil did impressions of Groucho Marx that reminded Greg of Hawkeye Pierce on M*A*S*H. Of course Phil would know how to get to Shea Stadium by train.

And of course Phil would know what to do at Shea Stadium once inside. This was no small thing to Greg, whose one previous visit was as part of a large day camp group. Greg had loved the Mets long before setting foot inside Shea. He yearned to know what he was doing and do it correctly. He wanted to be all the Mets fan he could be. So he kept an eye on Phil.

Phil grabbed a few All-Star ballots. Not a hundred, but a few. They let you do that, so Phil availed himself. If you lined them up, Phil demonstrated, you could punch out each desired hole several times at once. He voted fairly, not just for Mets. That’s how Greg voted in theory, and now it was how he voted in reality, the holes punching out efficiently, just as Phil had shown.

Phil bought a program, which was the same thing as a scorecard, something Greg didn’t quite realize all those years watching from home. The program/scorecard came with a small pencil. Phil used it to keep score.

Phil bought a pennant, featuring Mr. Met, Lady Met, another Mr. Met and Shea Stadium, all illustrated, all having a great time. It came on a wooden stick and Phil waved it in good fun.

Phil bought this slide rule-like contraption called the Baseball Brain. Greg had seen it advertised in the Post. It promised all kinds of special statistics attuned to all kinds of situations. It would tell you how Cleon Jones would bat against different kinds of pitchers, what would happen when Harry Parker faced different kinds of hitters. If Yogi Berra had this, the ads swore, the Mets would be in first place. As it was, the Mets were in last place. Greg thought you had to send away for the Baseball Brain. Phil knew how to find it at Shea Stadium.

More than things, Phil knew comportment. He knew you didn’t boo the retired umpires who were introduced on Old Timers Day; that you stood and applauded for the widows of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig; that you gave a long, rousing ovation for Casey Stengel when he made his grand entrance. Phil would have known not to jinx Jon Matlack by bringing up the possibility of a no-hitter. But the opposing pitcher, John Curtis of the Cardinals, singled in the third, so it wound up being a pretty suspense-free one-hitter.

After the Mets won, 4-0, with Suzan, Phil and Greg back on the LIRR platform awaiting the train that would take them to Woodside where they’d wait for a train to Jamaica (where they’d wait for a train to Long Beach), Phil gave Greg his pennant, his program and his Baseball Brain. Whatever the scope of his Mets fandom, he apparently wasn’t the kind to keep those sorts of trinkets — but he knew enough to give them to Suzan’s little brother. Greg knew enough to keep them. He still has the pennant and the program. He doesn’t know what happened to the Baseball Brain. He could’ve sworn he’d kept it, too, but somewhere over the decades, his Brain made itself scarce.

Suzan became a college freshman that fall while Phil and Nancy and some other names Greg recalls had one more year of high school remaining. Suzan went to NYU, using a name she didn’t have until just a little before that game at Shea Stadium. Suzan was “Susan” when she started high school, but not when she finished it. As she saw it, there was a surfeit of Susans, and she didn’t necessarily enjoy being one of many. Sometimes “Susan” would be called “Sue,” which works fine for many — Jeff’s wife, included — but wasn’t something Greg’s sister particularly cared for.

One day, in the high school newspaper office, Susan’s name was on the blackboard. Phil looked at it, picked up a piece of chalk and made an edit. Why not, he asked Susan, try it with a “z” where the second “s” now sits?

She did. She liked it. It stuck. Four decades later, it continues to stick. “Susan” is Suzan because of Phil. When Greg let her know what Nancy told him, Suzan was a) saddened and b) transported to that blackboard moment when she became, on the cusp of adulthood, an ever so slightly different person.

Rebranded, at any rate.

Funny thing — and there should be a funny thing here since Phil did a terrific Groucho and Nancy broke the news in a comedy club — is two days before his New York show, Jeff asked Greg something sort of out of the blue after many years of close friendship and constant correspondence. The club where Jeff was performing is owned by a fellow whose last name is Mazzilli. How many Mazzilli families could there be in and around New York? So Greg, while wondering if Comedy Club Mazzilli has anything to do with Lee Mazzilli, felt compelled to mention to Jeff that when Suzan worked at the registrar’s office at NYU, she issued a student ID to Alfred Matlack, the fifth cousin to Jon Matlack, who Suzan saw throw a one-hitter against the Cards during her first Mets game at Shea Stadium.

“She knew enough to ask if they were related,” Greg said. “That was the high point of my influence on my sister.”

“I’m impressed that Suzan did that,” Jeff replied, knowing she’s not a baseball fan. “BTW, explain the odd spelling. Is that her thing?”

Greg recounted the blackboard story as he best as he could remember it second-hand from when he was 11 and she was 17. Phil’s name didn’t come up in the explanation. That was Saturday. On Monday, Greg met Jeff’s wife’s Sue’s college roommate Nancy who went to high school with his sister Suzan who took Greg to his first Mets win, Phil leading the way and giving both the brother and sister something worth keeping four decades after the fact.

|

|